OUSEION - Memorial University's Digital Archives Initiative ...

OUSEION - Memorial University's Digital Archives Initiative ...

OUSEION - Memorial University's Digital Archives Initiative ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

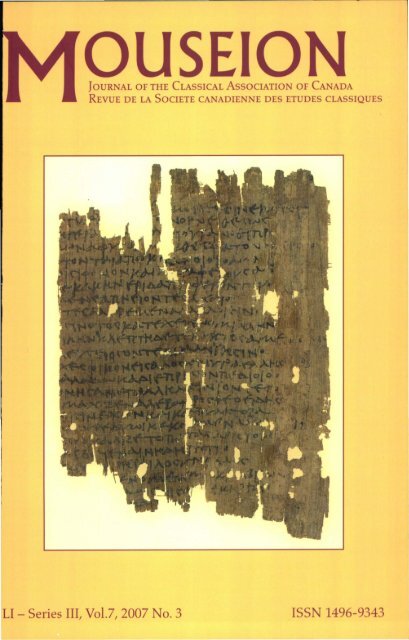

<strong>OUSEION</strong><br />

JOURNAL OF THE CLASSICAL ASSOCIATION OF CANADA<br />

REVUE DE LA SOCIETE CANADIENNE DES ETUDES CLASSIQUES<br />

LI - Series III, Vol.7, 2007 No.3 ISSN 1496-9343

M<strong>OUSEION</strong><br />

Jou rn al of th e Class ical Assoc iation of Canada<br />

Revue de la Societe canad ienne des etudes classiqu es<br />

L1- Series III. Vol. 7.2007<br />

A RTIC LES<br />

N O· 3<br />

Rory 13. Egan . The Prophecies olCalcluis in the A uJis Narra tive<br />

olAeschy lus ' Aga me m no n /79<br />

Jan ice Siege l. The Coens ' 0 Bro the l', Whe re Ar t Tho u? and<br />

l-lom er's Od yssey 2 13<br />

BOOK REVlE WS/ COM PTES REN DUS<br />

M. Finkelberg. Greeks and Pre-Greeks. A egean Pre his tory and<br />

Greek Her oic Tradition (Reye s Ber tolf n Cebri an) 247<br />

Br -uce Loude n. The Iliad . Str ucture. Myth. and Mea ning (Jona tha n<br />

Burgess) 25(}<br />

Justina Gregory. ed .. A Comp an ion to Greek Tragedy<br />

(C.W. Marshall) 253<br />

Dav id Kovacs. Euripidc a Ter tia (Ma rt in Cr op p) 257<br />

Pier re Fro hlich, Lcs CitL'S grecques et lc contro lc des m ngi strats<br />

(l V'-r sicclc ava n t j.-c.) (Cacta n Theria ult) 26(}<br />

Joseph Roism an. The Rhet oric olConsp iracy in A ncien t A the ns<br />

(Vir ginia Hunter ) 264<br />

Jaso n Koni g . Athletics and Literature in the Rom an Em p ire<br />

(N ige l 13. Cr ow ther) 267<br />

P.J. Heslin . The Tra nsvestite Achilles: Gender and Genre in Statius'<br />

Ach ille id (Rebecca Na gel) 27 /<br />

[aclyn L. Maxwell. Christinniz etioti and Com m unication in Late<br />

A ntiquity: John Clirysostotn and his Cong reg ation in A ntioch<br />

(David F. Buck) 274<br />

Werner Kre nkel. Nn tura lie non tur pin. Sex and Gender in<br />

A ncie n t Greece and Rom e. Sclirittcn 7 L11' antikc n Kultur- utid<br />

Sex ualwisscnsc luiIt {James [ope) 277<br />

P. Murgatroyd . Bella Schin va 283<br />

P. Murgatroyd. More Ep itap hs 284<br />

P. M urganoyd. A p is 286<br />

Index to Volume 7 287

Editorial Corrcspondcnts/ Conscil consultetii: Janick Aubcrger. Universite<br />

du Quebec a Montreal: Patrick Baker. Universit e Laval: Barbara<br />

Weiden Boyd. Bowdoin College: Robert Fowler. University of Bristol:<br />

John Geyssen. University of New Brunwsick: Mark Golden. University<br />

of Winnipeg: Paola Pinotti. Universita di Bologna: Jame s Rives. University<br />

of North Carolina: C]. Simpson . Wilfrid Laurier University<br />

REMERCIEM ENTS/ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

Pour l'aide finan ciere qu'ils ont accordee a la revue nou s tenons a<br />

rernercier' / For their financial assistance we wish to thank:<br />

Con seil de recherches en sciences humaines du Canada / Social Sciences<br />

and Humanities Research Council of Canada<br />

Dean of Arts. <strong>Memorial</strong> University of Newfoundland<br />

Dean of Arts. University of Manitoba<br />

Universit y of Manitoba Centre for Helleni c Civilization<br />

Brock Universit y<br />

Dalhousie Universit y<br />

University of New Brunswick<br />

University of Victoria<br />

We acknowledge the financial suppor t of the Government of Canada.<br />

through the Publication Assistance Program (PAP). toward OUI' mailing<br />

costs.<br />

Canada<br />

No part of thi s publication ma y be reproduced. store d in a retrieval<br />

sys tem or transmitted. in an y form or by any means. without the prior<br />

written conse nt of the editors or a licenc e from The Canadian Copyright<br />

Licensin g Agency (Access Copyrig ht). For an Access Copy r ight<br />

licence. visit www.accesscop yri ght.ca or call toll fr ee to 1-800 -893-5777.

MOUSeiOll aim s to be a distin ctivel y compre he ns ive Ca nadian journal of<br />

Class ical St udies . publishing articles and r eview s in both Fre nch and<br />

Eng lish. One issue ann ua lly is normally devot ed to archaeological top <br />

ics. including field rep orts. finds analysis. and th e hist or y of art in antiquity.<br />

The oth er tw o issu es welcome work in all ar eas of int erest to<br />

scholars : thi s includes both traditional and inn ovative research in phi <br />

lology. histo ry . philosophy. peda go gy. and r eception stud ies. as well as<br />

original work in and translations into C ree k and Latin .<br />

Mo uscion se prcsent e com me un pcriodique canadien d'etudes classiq<br />

ues polyvalent . publiant des ar ticles et comptes rendus en fr an cais et<br />

en ang lais. Un Iascicul e par annee est normal em ent dedi e a des sujets<br />

arch eologiques, incluant des rapport s p rcliminaires de fouill es. des<br />

etude s de mat eriel et des etude s dhistoire de l'art antique. Les deu x<br />

autres Iascicul es present ent des etudes dan s tou s les domaines dinterct<br />

pour les che r che urs. ce qui inclut a la fois les re cherches traditionnelles<br />

ou nov atri ces en philologie. en histoi r e. en philosophie et en ped agogi e<br />

ou relativ es a Iinfluen ce des etude s classiqu es en dehors du monde uni <br />

versita ire : Mo uscion publie cga leme nt des t ravaux ori ginaux rcdi ges<br />

ou traduits en latin ou en grec ancien.

NOTES TO CONTRIl3UTORS<br />

I. References in footnotes to books and journal articles should follow<br />

the forms:<br />

E.R. Dodds . The Gree ks and the Irrational (Ber ke ley 195 1) 11l2- 134 [not<br />

I02 H. ]<br />

F. Sandbac h. "So me p r oblems in Pr op ertius." CQ n.s. 12 (1962) 273- 274<br />

[not 273£.1<br />

For references which require departure s from th e above formats.<br />

see the mo st recent edition of The Chicago Manual ofStyle.<br />

Abbreviations of names of periodicals should in general follow<br />

l 'Attn ec Philologique.<br />

References to th ese standard works should follow the forms:<br />

V. Ehre nberg. RE 3A. 2 1373-1453<br />

lG 213 111826<br />

ClL 4.789<br />

TLL 2·44· 193<br />

2 . Citations of ancient authors should tak e the following form:<br />

PI. Sm p. 175d3-5 not Pinto . Sy mp osium 175d<br />

Tac, A nn. 2.6-4 not Tacitus. A ntuilcs (01' A nnals) 11.6<br />

Plu . Mol' . 553c not Plut a r ch . De sera numinis vindicta (or De sera) 7<br />

Abbreviations of names of Greek and Latin authors and works<br />

should in gene ra l follow LS] and th e OLD.<br />

3. Contributors should provide translations of all Latin and Greek.<br />

apart from single words or shor t phrases.<br />

4. Manuscripts submitted for consideration should be double spaced<br />

with ample margins. Once an article ha s been accepted. the author<br />

will be expected to provide an ab st ract of approximately ro o words.<br />

and illustrative material , such as tabl es. dia grams and maps. will<br />

hav e to be submitted in digital or cam era-ready form .<br />

5. The journal will bear th e cost of publishing up to six plates / illu stration<br />

s per article: fees will be charged for plates/ illustrations beyond<br />

thi s number. The cost of th e additional half-page plates / illu stration<br />

s is $12 each. of the additional full-page plates / illu strations $20<br />

each.<br />

6. Authors of articles re ceiv e 2 0 offprints fre e of char ge: authors of<br />

r evi ew s r eceive 10 offprints fr ee of charge . Additional offprints can<br />

be ordered at a mod est cos t.

AVIS AUX AUTEURS<br />

I. Les re fere nces au x oeuvres mod e rn es d oivent etre formulees co m me<br />

Ie montrent les exe m p les suiva nts:<br />

A .T. Tuilier. Etude com p aree du tcxt c ct de s sc ho lics d 'Euripidr. Pill'is,<br />

1972, pp . 101-1 23 [/10/1p as 101 fLI<br />

1'. C ri ma l. « Pr op er ce et la legen de de Tarpeia » . NEL 30 (1952). p p. 32-<br />

33 [/10/1pas 32LI<br />

Da ns les cas exce ption nels Iorm uler se lon les rcgles de ledi tion la<br />

plu s r ecente de The Chicago Man ual o f Sty le.<br />

POUI' les titres de pcriodiques. utili ser les abrcviations e m p loy ees<br />

dan s L"Annce Pliilologiquc.<br />

C iter co m me suit ces reuvres de ba se:<br />

V, Ehre nber-g, NE IIIA.2. 1373-14 53<br />

IC 2!3 10026<br />

ClL 4.709<br />

TLL 2. 44. 193<br />

Les r eferen ces a ux auteu rs a ntiq ues d oi vent etre Iormulees co m me Ie<br />

rnontr ent les exe m p les suiva nts:<br />

Plat on . Banquet, 175d . /10/1 p as 1'1.Smp. 175d3-4<br />

Tacite . A /1/1alcs . l!. 6. /10/1 p aS T ilc. A /1l1.2.6.4<br />

Plutarque . De scro numinis vindictn (o u De sera) 7-0. /10/1 pa s PIll. Mo r.<br />

553c- e<br />

3. Pr-ic r e de traduire to utes les cita tions du lat in o u du gl'ec. sa u f les<br />

mot s sim ples et les locuti on s co urtes.<br />

4. Les manuscrits soum is a l'cvaluation doi vent cne en double int erlign<br />

e a vec d 'amples marges. Une Ioi s un e co m m unica tion acce p tce ,<br />

l'auteur doit en fournir un resume de 100 mot s envi r on. et Ie mat e riel<br />

dillust r ation-e-ta blea ux, di ag rarnrnes, ca rres-i- d oir etre so umis<br />

so us Io rme p r ct e a la re p rod uction.<br />

5. La re vue s'occ upe des Ir ai s d 'edition jusq u'a six plan ches / illu strations<br />

pal ' co m m unica tion: l'auteur doit porter les Irai s a u-de la de ce<br />

chiffre. Le cou r de chaq ue plan che /illustration en derni -p age est de<br />

12 $ , et Ie cout de chac une en page es t de 2 0 $ .<br />

6. L'a ute ur dune co m m unica tion r ecoit gra tis 2 0 ti res a part: l'auteur<br />

dune revue cr itiq ue en r ecoit 10 grn tis. O n peut co m ma nde r des ti<br />

I'CS a pa rt sup p lc rne nta ires a un cout mod est e.

ABSTRACTS/RESUMES<br />

T HE P ROP HEC IES OF CALCHAS IN THE AULIS N ARRATIVE OF<br />

AESC HYLUS ' AGAMEMNON<br />

RORY B. EGAN<br />

Da ns Aga me m m non 104- 263 . le chre ur relat e les eve ne me nts qui se sont<br />

deroules a Aulis. No us proposon s un e nou velle lectu r e de ce passage et<br />

avancons plu sieu r s nouv elles interpre tatio ns sy nta xique . semantique et<br />

mythologiqu e. II en r esult e pou r la piece et tout e la trilo gie des implications<br />

poetiques, dr am atu r giqu es. mo rales et th eologiqu es. Nou s etayons ici des<br />

argume nts que nou s av ions deja invoqu es en 1979 en posant en pr ernisse que le<br />

discou rs uttr ibue a Ca lcha s (aux vel's 123- 125) continue pend ant tout r«hymn e a<br />

Zeus » et jusqu 'a la fin ale au vel's 183- Ce discours ne connai t qu 'un e br eve<br />

interruption a ux ve l's 157-1 58.<br />

T HE COENS' 0 BROTHER. W HERE A RT TH OU?<br />

AND H OMER'S ODYSSEY<br />

JANICE SIEGEL<br />

Une comparaiso n entre r Ody ssee d'Hornere et Ie film O ' Broth er des Ircr es<br />

Coe n (titre origina l : 0 Bro ther Where Art Thou ? 2 ( 0 0 ) rcvele entre Ies deu x<br />

oeuv re s des liens nominau x. nar r atif s et episodiques eto nna rn me nt etroi ts. Ce<br />

film non seulern ent evo que Ies int ri gu es tr ou vees chez Hom er e. son ar t du<br />

port rait et ses motifs mythiques. rnai s au ssi il cree. en combinant ces cleme nts.<br />

un texte cornique tout a fait uniqu e et ori ginal. Tout au long du film. les<br />

naitem ent s de topoi cpiques ana log ues (par ex. les mena ces contre la culture . Ie<br />

r ole des dieu x et leu rs apparences ph ysiqu es. les natu res opposee s « des bons et<br />

des mechant s ») do nnent mati ere a ref lexio n rant sur l'adaptati on moderne qu e<br />

sur le modele antique.

Mouseion. Se ri es III. Vo l. 7 (21)(17) 179-212<br />

'02 11 J7 Mo uscion<br />

THE PROPH ECI ES OF CALCHAS IN TH E A ULI S N ARRATI V E OF<br />

A ESCHYLUS' AGAMEMNON<br />

RORY B. EGAN<br />

Thi s ess

180 RORYB. EGAN<br />

straightforward alternative. requiring no textual adju stments apart<br />

from additional modern punctuation. effects a fundamentally different<br />

and. I maintain. a more plausible accommodation of the "hym n" to its<br />

immediate and extended contexts. Response to it. though. in the burgeoning<br />

scholarship on the Ore steia of the past generation has . to say<br />

the least. been muted. New critical editions. full commentaries. numerous<br />

translations. and do zen s of monographs. articles. notes. reviews<br />

and critical bibliographies. often dealing directly with the same pa ssage.<br />

express neither endorsement nor refutation. (The only apparent exception<br />

is R.O. Dawe. whose brusque dismissal I review in the Afterword.")<br />

In the meantime. difficulties which simply vanish when the verses are<br />

assigned to Calchas continue to exercise interpreters. including sever al<br />

who puzzle over references to the future (of which the chorus must be<br />

unaware) while ignoring the available suggestion that they are spoken<br />

by a prophet." Others regard the "hymn" that putatively interrupts the<br />

narrative. as an interlude," a "cushion .l'or even "a major punctuation<br />

mark.?" The present reading regards the perceived switching back and<br />

forth between dramatic pa st and present as illu sory. a con sequence of<br />

misreading at a cr ucial juncture. The case for seamless integration of<br />

the "hymn" into the Aulis narrative will adjust. rather than repeat. my<br />

arguments of 1979. while elaborating a demonstration of how the passage<br />

"w or ks" as continuation of Calchas' prophecy. One set of critical<br />

premises applies when the narrator-chorus. remote in time and place<br />

from Aulis. is perceived to be the speaker : a fundamentally different set<br />

when the prophet is perceived to be speaking at th e time and scene of<br />

the portents and in the presence of the Atr eids to whom those portent s<br />

directly pe rtain.<br />

TR ANSLATION AND S YNOPSIS<br />

The overall effects of the alternative reading are reflected in the following<br />

provisional translation. ba sed on West' s text'" (with specified excep-<br />

6 I now. while th e pr esent article is in proof. not e a bri ef ref er en ce by Ma r <br />

tin a 200T 25.<br />

7 So e.g, Conac her 1976: 332 discussed fu rther below: Degen er 200 1: 77-79<br />

who eve n com pares th e "hym n " to a prophecy by Cassa nd r a: Dawe 1999a: 40:<br />

1999b: 70.<br />

s See e.g. Ber gson 196T 22: Smith 1980: 3- 4: Hogan 1984: 4 1: Wegbge 1991:<br />

265. 279: Thiel 1993: 87- 110: Co ur t 1994: 196-1 97: Schenkel' 1994: Sommerst ein<br />

1996: 170 and 20g: Ce isse r 2002: 260.<br />

YSo. respectively. Rosenrn eyer 1982: 279-2 80 and West 1999b: 78.<br />

"' West 1990a. sup pleme nted by th e editor's com me nts on va rious passage s in<br />

West 1990b: 174-18 1a nd 1999a.

TH E PROP/ -IECI t.:J OF CA LCI-IA S /8 /<br />

tion s). and sy nops is whi ch also a nticipate th e various inter -pr eti ve argume<br />

nts on wh ich th ey rest.<br />

( 10 4-2 0 ) Since my stage of life . being naru rall y s uited for it. still<br />

breathes fo rt h th e pe rsu asive stre ngth of song inspired by go ds, I a m<br />

a uthorize d to ex pound up on th e fat eful powel ' in volving th e exped ition<br />

a nd re lati ng to th e men endow ed w ith a uthori ty : on how th e ilgg l'essive<br />

bird disp at ched th e two-throned powel ' of th e Ac hae a ns , the likeminded<br />

com ma nders of th e youth of Hell as, and a long with th em th e<br />

weilpons a nd th e activa ti ng milnp ow el'. a nd how to th e kin gs of ship s<br />

th e kin g of bird s, one dark a nd th e othe r: w hi te- tai led. ca rn e into view<br />

in th e clea r es t region of the s ky close by the bu ild ing 's peak Irorn the<br />

s ide on w hich the s peilr is w ield ed : a nd how the y fed up on t he bro od of<br />

ha re s. teeming w ith fecund ity , ba rr -ed Irom th e runnings th at wo uld<br />

hav e been .<br />

(12 1) -So n 'o w . SOlTOW, do ex p l'ess : but good shall be victo ri ous .c<br />

( 122-3H) The army's ca re ful prophe t sa w the pai r. di vid ed in their<br />

mean ings, a nd he recog nized the bell ige rent Atreids. the feasters on<br />

the ha re s . th e ma rsh all ing lenders. He s poke as fo llow s in int erp ret ation<br />

of th e pOl'tent s. " In th e co ur se of tim e thi s expe d ition w ill plunder<br />

th e city of Pr-iam while Fate . perforce . w ill plunder th e herds . th e<br />

ab unda nce of th e peopl e. in Ironr of th e tow el's. I onl y PI'ilY th at no<br />

go d-se nt r ui no us delu sion I I will be-cloud th e Grea t Troy-Restraine r.<br />

str icken in adva nce as he is ru shed along." e m bro iled in t he a rmy's<br />

vent ure. FOI' chas te Artem is in her pity . resent ful of her Iathers<br />

w inge d dog s w ho are th e im mo lato rs of the pitiable cow e r-ing cre a ture<br />

aIOIl}; with lict : OWIl childre n bctorc tlirv wcrc born [ 01 ' th eir o wn<br />

blood tel oti ve because of the ar my l. despi ses th e eag les ' ban qu eting."<br />

( 139) - SOITOW. SOITOW. do ex p l'ess : but goo d sha ll be victol"iou s.<br />

( 140- 53) " Heka te is so w ell -mi nd ed tow ar -ds th e tender yo u ng lings ':' of<br />

Iiery lions and so pleasant to th e thriving . eager nu rsl in gs of a ll th e<br />

bea st s th at ha u nt th e countryside. ':' She dem an ds tha t theil ' port en ts<br />

co me to pilSS. th e favo urable indi cators but a lso th e inau s piciou s ones.<br />

In case . th ou gh . she should brin g a bou t Io r th e C re eks some timecons<br />

um ing . sh ip- im ped ing per -iod s wh en there is no sililing becau se of<br />

contl'ilry w ind s. thi s in her eilge n1t'SS fOI' a not her sacrifice. a la wless<br />

one . devoid of feasting . a n int ernecin e ca use of contentio us ness th at<br />

" With "r-uinous delu sion " I «v to co m bine the mean ings of the mss. aTO as<br />

ITcogni zed by Ferrrui 199T 12- 17 w itho ut p re cluding Hermann's ayo read by<br />

West.<br />

I .' With "stri cke n in adva nce as he is ru sh ed a long ." I a tte m pt to ca pture two<br />

di fferent meanings of TT pOTVTT EVas exp laine d belo w.<br />

I J Read ing . wit h Wella uer 1H23, bp ac o ic i AETTTOIC, def end ed in Egiln 2ooH.<br />

1.1T his Eng lish se ntence transla tes a C re ek s ubor dinate cla use w hich I consnue<br />

wi th both th e pre ced ing a nd the follow ing se nte nce. Con ve ntions of p unctu<br />

arion . in C re ek 01 ' Eng lish. do not accommo da te th is. so th e re see ms no alternative<br />

to isol ating th e cla use as a se pa ra te se nte nce . O n problem s of pun ctu ation<br />

a nd se nse here d . Dege ne r 200 I : 6H-69.

THE PROPHECIES OF CA LCH AS<br />

edy for' the bitt er stor m . more gl 'ievous Ior th e lead e rs . so that th e<br />

Atre ids struck the gl 'ound with th eir sta ffs and did not contain thei r<br />

teal 's. he spoke in th e following words, the se nior ruler did ,<br />

(206 -1 7) "It is a gri evous doom not to obey, Gri evous . too . would it be<br />

if I should but ch er my child, the adornment of my home. befouling my<br />

pat ernal hands beside the a lta r with th e drippings from th e sla ughte r<br />

of th e maiden , Whi ch of th ese is Ire e Irorn evil? How could I be delinquent<br />

to my fleet and negle ctful of the alli an ce? For she [Artemi s] vehem<br />

ently desi re s the maid en 's blood as a wind-stopping sac ri fice.<br />

though ri ghteou sn ess forbids it. 's May it be for' th e best. "<br />

(2 1H- 37) Afte r he put on th e harness of co m p ulsion . a iri ng a n att itude<br />

of mind that was impious. co r-ru pt and ilTeligious. Irorn th at point he<br />

cha nge d to a cas t of mind that would venture anything, F OI ' g ri evous<br />

confus ion. th e so urce of suffe ri ng. advises sha mef ul co nd uct and make s<br />

men impetuous, He wa s em bolde ned . accordingly. as s u pportel' of th e<br />

hostilities for th e red emption of a woman, to be th e immolator ' of his<br />

daughter: and he und ertook preliminary rituals on behalf of th e fleet ,<br />

The battle-ea ger decision-makers disr egarded her pleadings and IWI'<br />

a ppea ls to her father - as well as the maidenly stage of her life, Her fath<br />

cr directed fun ctionaries. following a pl 'ayel ', re solutely to tak e her<br />

a nd rai se her up. as if she were a young goa t. above th e a ltar. bound up<br />

in her r obes and pa ssive . and to chec k with a re straint. with th e fo rc e<br />

and muting stre ng th of mu zzle s. a ny utteran ce Irorn th e mouth in her<br />

fail ' face that might hex her family,<br />

(23H- '17) She , letting her ye llow-tinte d clothing flow down to the<br />

gl'Ound. shot ea ch of her sac ri ficers with a pitiable shaft Iiom her eye s.<br />

as clear-ly as in pictures . int entl y besee chin g them. becau se she had Ir equ<br />

ently s ung at her father 's banquet s for' th e men a nd . as on e unmat ed.<br />

fondl y honoured with her PUI't' vo ice her Iarh ers a us picio us paean a t<br />

its third libation.<br />

(24H-63) Eve nts frorn th at point on I do not know 101 ' did not se d,''! nor '<br />

am I talking about them. but th e skills of Ca lchas are not without valid <br />

ity , Justic e distributes knowledge to tho se who have undel'gon e ex pc ri <br />

c nce . Wh en ever th e future OCCUJ 'S you will hea r of it. Let it be anticipat<br />

ed with a wel com e balanced by th e anticipation of p 'ief. It sh all<br />

come clea r-ly togethel' with th e I'ays of dawn ,<br />

The translated pa ssage begin s aft er th e chor us ha ve que stioned<br />

Clyte mnes tr a for up -to-date information and asserted their competence<br />

to report on events at Aulis. Afte r doing so th ey close by ob serving that<br />

the y hav e nothing fur -ther to s

ROR YB. EGAN<br />

rative within the doubl e brackets thus form ed incorpor ates pa ssages of<br />

qu oted speech whi ch . as fr equ entl y in poetic nar rative. are set off by<br />

demarcating phrases that se r ve as audible quotation marks." The fir st<br />

spee ch is introduced with OtfTW 0' ETTTE TEpol;wv at 125 and broken off at<br />

156-7 wh en the nar rating chorus int er vene with TOIOOE KOAXac ...<br />

oTTEKAaYSEv. In both places the spea ker is specifically ident ified :<br />

CTpaTOlJaVTI C ( 123); KOA Xa c (156) . The phrases follow ing Calchas'<br />

op enin g words. th ough. actua lly mark a transiti on to a differ ent . but<br />

r elated . sequence of words by the same speaker . So Ca lchas r eported on<br />

th e port ent s. concentr ating in the fir st part of his r ep ort on Ar temis<br />

with her int er ests and att r ibutes and . in a consistent and approp r iate<br />

seq uel theret o (r otc 0' ouoqxovov. 158). balanced it with the second pa rt<br />

in whi ch he shouted forth his th ou ght s on relevant characteristics and<br />

pow er s of Zeu s ( 160-83) . In the fir st part Calchas doe s not name Ze us;<br />

in th e second part he does not menti on Ar temis. Whe n th e chorus have<br />

finish ed qu otin g him. cha nge of subject and re sumption of the nar rat ive<br />

ar e ma rk ed by Ka! TOe' ( 184) , a com mo n brid gin g term in epic nar rative.<br />

Now the chorus re port fir st on Aga me mno n's reaction to the<br />

proph ecy and to subsequent eve nts (185-98). and then on a further pronouncem<br />

ent fr om th e proph et (19 8- 202) . That lead s int o a direct qu otation<br />

of Aga me mno n (20 6-1 7) which is introduced in a conv entional<br />

transiti on with avas 0' 0 rrpscpvc TOO' E TTE qxovcov (205) and closed at<br />

218 wh ere ETTE! 0' simultaneously marks the next resumption of the narrat<br />

ive. Th e na r rat ive th en lead s to the second address to Clyte mnestra.<br />

The Clytemnestra-to-Cly temnestra sequence can be summariz ed as<br />

follows:<br />

I . Qu er y addressed (c u O· ... KAVTOlIJTlCTpa) to Clyte mne stra (83- 1( 3)<br />

2. Preliminary statement of chorus ' compe te nce ( 1°4-6)<br />

3. Ope ning of Aulis nar rative: Calcha s and port ent s (10 4- 20)<br />

4. Att ri b ution and direct qu otation of Calchas . bis ( 122-83)<br />

5. Reaction of Agamemno n . i]YEIJC:.W 0 TTpEC[3VC (184-98)<br />

6. Rep ort of spe ech by Calchas (199-202)<br />

5. Reaction of Aga memno n . a v aS o· 0 TTpk[3vc (2°3-5)<br />

4. Attr ibutio n and dir ect quotation of Aga mem non. (2°5 - 17)<br />

3 . Closing of Aulis nar -r at ive: Aga me mno n and sacr ifice. (2 18-46)<br />

2. Co ncluding statement of chorus' limit ati on s (248-57)<br />

1. Q uery addressed (K AVT a \l.Hic Tp a .. . cu 0') to Clytemnestra (258-63)<br />

200 n difficu lties in deter minin g bou nda ri es of ora tio recta see e.g. Athanassaki<br />

199]: 150 and 153 : Bel'S 199T 24 and passim .

RORYB. EGAN<br />

"stricken in advance," before the bit-piece has curbed Troy, it applies<br />

fittingly to both Agamemnon and his army. But the intransitive<br />

TTpOTVTTTW means "r ush forward," usually under some force or pressure.<br />

The Aeschylean mutation of the verb. if applied to Agamemnon.<br />

can suggest a person being "rushed along," acting impulsively. A whole<br />

alternative range of possibilities for both TTpOTVTTEV and CTpOTW8EV<br />

opens up if the TTpOTVTTEV and CTpOTW8EV is a military objective. The<br />

Triclinian scholia. routinely ignored by modern commentators on this<br />

passage. explain the CTOIlIOV Tpoioc as a point of entry into Troy. previously<br />

battered (TTpOTVTTEV) in military action (CTpOTW8EV). Earlier<br />

batterings of Troy were a matter of "history" by the time of Agamemnon"<br />

who, as a military leader with Troy as his objective. might naturally<br />

be susceptible to a military reference in the overclouding of the<br />

CTOIlIOV Tpoicc.<br />

The protean language is sustained in the next verses (134-7) by "an<br />

astonishing feat of amphibological dexterity."?' There is no better demonstration<br />

of the doubleness of the portents' significance to Calchas<br />

than his description of the reasons for Artemis' displeasure: OVTOTOKOV<br />

TTpO Aoxov uoyspcv TTTCxKO 8vOllEVOICIV (136-7) . This, as Lawson noted,<br />

can be translated in the following two ways. (I) "Slaying a trembling<br />

hare and its young before their birth." (2) "Sacrificing a trembling cowering<br />

woman, his own child. on behalf of the army."?"By one rendering<br />

the words address the recent actions of the eagles. by another the imminent<br />

actions of the Atreids. The cumulative double-entendres typify<br />

the entirety of Calchas' bi-partite prophecy. Calchas continues with an<br />

ornate disquisition on Artemis' affections for young animals in which<br />

the jingly terminology for the little animals. simultaneously evocative<br />

of dew and rain." also makes a topical allusion to Artemis' responsibility<br />

for weather, albeit here with intimations, both accurate and misleading,<br />

of beneficence. Her tender sentiments for the new-born and the<br />

connotations of gentle moisture are antithetical both to the fieriness of<br />

the adult animals and to the threat of internecine violence and foul<br />

weather of which Artemis would also be the originator. Calchas' conclusion<br />

regarding the goddess's will. correspondingly divided. is that<br />

the twofold signs. the positive ones and the negative ones that involve<br />

culpability (KOTCxIlOIl

[94 RORYB. EGAN<br />

vant to Ca lchas ' r ep r esentation of Artemi s. For one thing. en vy or re <br />

sentme nt and a blind. r efle xive . irrational and w rathful ven gean ce are<br />

pe r sistent attr ib utes of th e goddess that are some times ar ouse d by inadvertent<br />

transgr ession of her prerogatives." She retaliates with punitive<br />

mea su r es th at ar e onl y r eliev ed by a compen sat or y sac r ifice. sometimes<br />

of young human victims. The cult myth of Ar te mis at Brauron is<br />

particularly analogou s to th e case of th e eag les and th e ha r e at Aulis<br />

(itself a site of Ar te mis cult '") . At Br au r on , when an ger ed by th e chance<br />

killing of a bea r in her sanctuary she r etaliated with a pla gu e that was<br />

reli eved by th e ann ual sacr ifice of an Athe nian maid en ." Such char acteri<br />

sti c incide nts make her dem and s for a compe ns atory sacr ifice at<br />

Auli s predictable. conforming as th ey do to th e patt ern by wh ich . pa rado<br />

xicall y. her kindliness accompanies. ind eed motivates. cr uelty .'? Thi s<br />

info rms th e double sense of th e adjective TEKVOlTOIVOC de scribing an anger<br />

that has off sp ring both as sacr ificial victims (Icve re ts and Iphi geneia)<br />

and also as ave nge rs (Clytemnestra an d Orestes )." Th e patt ern of<br />

th e ha r e-slau ghter and its sequel is thu s also a pa radigm for th e old or <br />

der of r et ributive slay ing that figu r es so prominently in the dramatic<br />

and ethical dialectic of th e trilog y. If th e r ationa le for th e sacrifice of<br />

lphigen eia see ms "cr ude and inad equat e."7 1 that only aligns it with a<br />

centr al th em e of th e trilogy. th e cr ude ness and inad equacy of vendett a<br />

justi ce."<br />

The "lo gic" of Ar te misian re tr ibution bear s upon anothe r instan ce of<br />

semantic and sy ntac tic flexibility in th e context. Th e po siti ve. 01 ' optimistic.<br />

content of th e p rophet' s flu ctu ating words on Ar te mis ar e confined<br />

in their entirety to verses I40-3. a sing le clau se introduced by th e ambiguous<br />

TOC OV rrsp . It see ms impossibl e to det ermine wh eth er th e<br />

ph r ase is con cessive or emphatic w ith cau sal and exp lanatory over <br />

ton es": wh ether . th at is. it ind icat es that Ar te mis is partial to fulfillmen t<br />

of th e por tent s despite her selecti vely kind disp osition. or because of it?<br />

Knowin g both th e cause of he r an ger (sla ug hter of yo ung victims) and<br />

its con sequen ce (sla ug hter of a yo ung victim). we mu st re cog nize both<br />

h6 Effec tive ly dem on st r at ed by Furl ey 1986: I 18. Cf. Clinto n 1988: passim.<br />

67 See Furley 1986: [19.<br />

hHSee w ith referen ces to testimoni a.<br />

!>90n thi s point d . Lloyd-J on es [983: 88.<br />

iOC£.Gei sse r 2 0 0 2 : 2 6 r ,<br />

7 1See Fur-ley 1986: I [ 0 . with reference s to ea rli er cr iticis m.<br />

7 2 See Belfiore 198T 6 on ana logie s bet w een Ar te mis and th e Eri nyes in th e<br />

trilo gy.<br />

i3 For discussion and r eferen ces see Conacher [98T 82: Fur-ley 1986: 1[8.

SACRIFICERS<br />

Y OUNG SACRIFICIAL<br />

VICTIM<br />

VICTORS<br />

VANQUI SHED<br />

RORYB. EGAN<br />

Artemis-oriented perspective<br />

PORTENT<br />

Eagl es<br />

Hare-brood<br />

Zeus-oriented perspective<br />

PORTEN T<br />

Eagle s<br />

Hare-brood<br />

PORTEND ED<br />

Atre ids<br />

Iphigeneia<br />

PORTEND ED<br />

Atreids<br />

Troy<br />

This particular set of differences, however. represents only one register<br />

of significance . and more elemental differences between the two god s<br />

are brought out in the two parts of the Calchas quotation.<br />

The threatening tone at the end of Calchas' Artemis section is miti <br />

gated by his hopeful declaration that he is invoking Paean, a divinity<br />

who might forefend or remedy the threatened adversity . The Artemis<br />

section thus anticipates an anti-Artemis. Who is thi s Paean? The generally<br />

assumed pos sibility that it is Apollo? might have long-term implications<br />

for the conclusion of the Atreid myth and the trilogy, but as a partisan<br />

of the Trojans in the shor ter term Apollo is an unlikely divinity for<br />

any competent prophet to invoke as the counter-force to Artemis.<br />

Paean, moreover, had sever al identities, one of which wa s Zeu s.7 H Can<br />

Zeus, then, be the anti-Artemis of the prophet's invocation? Certainly<br />

he is th e only other divinity to figure in the portents, and in conn ection<br />

with eagle -portents during a military venture there is rea son to s uppose<br />

that an Athenian audience might have reflexively thought of Paean<br />

as Zeu s. An Athenian military leader. Xenophon (An. 3.2.9). reports an<br />

incident. less than sixty years after the production of the Ore steia. in<br />

which a pa ean is sung after an eagle. seen as an omen of Zeus as deliverer<br />

(cco-rfip), has appeared to his troops." Once the po ssibility ha s been<br />

raised of Zeus as the Paean invoked by Calchas. oth er con siderations<br />

present themselv es in corroboration. Specifically. in the subsequent account<br />

of preparations for the sacr ifice of Iphigeneia there is a ref er enc e<br />

to her having sung in her father's hou sehold at the third libation of the<br />

paean (245-7). The fact that the third libation wa s conventionally in<br />

771n Egan 1979 : 5 I accept ed th e com mon assumption that it is Apollo.<br />

7HCf. Gr oene boom 1944 : 148-149.<br />

7YCf. Kappel 1992: 45.

2 06 RORYB. EGA N<br />

petuously and in a mental mode that is ovccE13ii. avoyvov. cvlspov.<br />

Here the terminology of the "mind " (rppsvoc. opovstv) echoes the Zeu s<br />

pa ssage. but there is no success ful attainment for the mind (such as had<br />

been expressed by TEVSETOI cppEVWV TOnov. 175). and no soundness of<br />

mind (c corppovs iv ). just confirmation that coxppovsrv pa sses by those<br />

who are not inclined to it. In turning abruptly from acquiescence with<br />

the prophet's words on the all-powerful victor who is Zeu s. Agamemnon<br />

succumbs to th e overclouding delu sion of Ar temis. "? of which Calcha<br />

s had warned earl ier .<br />

Sinc e a connection between Iphigeneia's singing of paeans to Zeu s<br />

and Calchas' appeal to Zeu s Paian ha s alread y been noted. and since<br />

there is nothing further in th e remainder of th e narrative on th e preparations<br />

for the sacr ifice that affects. or is aff ect ed by, the attribution of<br />

160-83 to Calchas . I proceed to the closing verses of th e Auli s narrative.<br />

Here again the attribution of the "hymn" is of con siderable con sequence.The<br />

na8EI lla80c axiom is invoked again. and again it is in association<br />

with Calchas . Thi s time. although th e phrase is sp oken by th e<br />

chorus in their own voi ce. it seems that th ey attribute it specifically to<br />

Calchas, thu s r eflecting th e prior occurrenc e of the axiom within a<br />

speech by Calchas him self. What happens here is that the chorus declin e<br />

to give details about th e fate of lphigen eia and then observe that th e<br />

crafts of Calchas do have validity. Thi s can of cour se be a euphemi sti c<br />

way of say ing. with past refere nce now. that Calchas ' pronouncem ent s<br />

determined the still un sp ecifi ed fate of lphigen eia about which the choru<br />

s might be ignorant. It is hardly implausibl e in th e context. though. to<br />

discern a referen ce to Calchas espousal of th e na8EI lla80c do ctrine.<br />

Th e chorus will not talk about the particulars of lphigeneia's fat e but in<br />

du e course people will find out about it. and about other things. In any<br />

case it is in th e ver se (250) immediately following the mention of Calcha<br />

s' name that th e no8El llo8oc axiom recurs. along with a glo ss that<br />

extends into the following verse . Is it only an accid ent that th e proverb<br />

is adjac ent to Calchas' name and th e referen ce to the validity of his<br />

skills . or is the proverb actually being attributed to him here as it wa s.<br />

according to my int erpretation. by the sa me chorus earlier on in th e<br />

same ode ? In the latt er case thi s second ref erenc e to th e no8EI llo8oc<br />

principl e is also a retrosp ective gloss on th e fir st on e. making it clear to<br />

th e audience that Ca lcha s was warning Aga me mnon against impetuous<br />

initiatives.<br />

Thi s closin g reminder of th e dictates of Calchas delivered by th e eld <br />

ers to th eir auditors at Arg os, and to th e aud ience in Athens . serves also<br />

I"?e £. Edwar ds 197T 26- 28 on "folly " or "infatuation " in Aga me m non's decision.

2 12 RORYB. EGA N<br />

_ _ . ed. 1989. Aeschylus. Eume nides. Ca mbri dge .<br />

__. 1995. "Aesch. Ag. 104-1 59: Th e om en of Aulis or th e om en of Argos."<br />

M useum Cri ticum 30- 31: 104-159 .<br />

__. 1996. Aeschylean Trage dy . Bar i.<br />

Sta nfor d. W.B. 1939. A m big uity in Gree k Literature: Studies in TheOIY and<br />

Practice. Oxford .<br />

Sulliva n. S.D. 1997. A eschy lus ' Use of Psychological Terminology. Montre<br />

al/Kings ton/ London /B uffa lo.<br />

Thi el. R. 1993. Chor und tr egische Handlung in .Agem cm non' des A ischylo s.<br />

Stuttga r t.<br />

Thomson . G.. ed. 1966. The Oresteia ofAeschylus. 2 vols. Ams te r dam / Prague .<br />

Tyr ell. W.B. 1976. "Zeus and Agamemnon at Aulis. " Cl71: 328- 334.<br />

Vidal-Naquet . P. 1973. "C hasse et sacr ifice dan s r Oresti e:' in P. Vernant and P.<br />

Vidal -Naquet, eds . My the et tragcdie en Grece ancienne. Pari s: 133-1 58.<br />

Weglage. M. 1991. "Leid und Er kenntnis: Zum Ze us-hy mnos in aischyleische n<br />

Agamemnon: ' Hermes I 19: 265- 28 I.<br />

Wellau er. A.. ed. 1823. Aeschyli Treg ocdiae. 3 vol s. Leip zig.<br />

West . M.L.. ed . 1990a. Ac schy li Trag ocdiec cum incetti poctee Prometh eo. Stuttgart.<br />

__. 1990 b. Studies in Aeschylus. Stuttgart.<br />

__. 1999a . "Aeschylus. Aga me m no n 104- 59: ' Lexis IT 4 1-6 1.<br />

__. I 999b. Comment on Dawe 1999b. in Lcxis IT 78.<br />

Wilk en s. K. 1974. Die ln tcrdcpcndcnz z wischen Trago dienstr uk tur und Theo logie<br />

bei A ischylos. Munich.<br />

Willink. C. 2004. "Aeschylus. Aga me mnon 173-1 85 and 205- 217." QUCC n.s. 7T<br />

43-54·

2[6 JANICE SIEGEL<br />

The Coens' purported ignorance of Homer's text-together with<br />

their well-known fondness for movies of pa st era s-has led some critics<br />

to conclude that the brothers actually got their knowledge of the Odyssey<br />

from Kirk Douglas' Ig54 film Ulys ses (G. Perry 20 0 0 and Danek<br />

200 1: go) or even from the Clas sics comic version of the tale (Hunter<br />

200 0, Taylor 20 0 0 , and Danek 20 0 I: go) . 13 In fact , in interview re sponses<br />

ostensibly designed to prove the limited influence of Homer's Ody ssey<br />

on the film . the Coens reveal a much more-than-passing acquaintance<br />

with the text:<br />

Ethan: We avail ou r selv es of [th e Odyssey ]very selectively. The re's the<br />

sire ns: and the Cyclops . John Goodman, a on e-eyed Bible sales ma n .. .<br />

Joel: Wh en ever it' s conv eni ent we trot out the Ody ssey.<br />

Ethan: But I don 't want any of the se Ody ssey fan s to go to the movi e<br />

expecting, yknow .<br />

Joel: "Wh er es Laertes?" (laughter )<br />

Ethan: "Wheres his do g? " (more laughter}'!<br />

In fact. although its details are of course very different, 0 Broth er doe s<br />

indeed follow the gen eral narrative template provided by the Odyssey.<br />

Yet the Coens mock tho se who look only for supe rf icial plot parallels<br />

with the Odyssey<br />

"Scy lla and Cha ry bdis? Where were they? " pu zzle s Ethan. Th e whirlpool<br />

at th e end , sure ly? "Oh." the brother s cho r us , "the whirlpool."<br />

Ethan gr ins pen sively. "Oh , yeah, sure. Scylla and Cha r ybdis" (Romn ey<br />

2 ( 0 0 ).<br />

No, in 0 Brother Scylla is not a man-eating monster, nor is Char ybdis<br />

a whirlpool. They represent in the adaptation exactly what they repre<br />

sent in the original: a difficult choice between two equally undesirable<br />

options. 15 Just as Ody sseus had to navigate between Scylla and Charybdis<br />

twice before he could reach safety (Od.12.28g-338. 544-70). Everett.<br />

Pete, and Delmar twice avoid a similarl y dista steful choice-death or<br />

I31n an interview in th e "Pr oduction Fea ture tte " of th e DVD , Joel Coen explains.<br />

"We sor t of combined th e Three Stoo ges with Hom er 's Odyssey" (d . an<br />

int ervi ew with George Clooney in Bergan 2 0 0 0 : 2 I 2 ). By critics, 0 Broth er ha s<br />

been dubbed ''' Bonnie & Clyd e' as told by Monty Python " (Tura n 2 ()() 0 ) and<br />

"Mad Maga zin e's version of ' Let Us Now Praise Famous M en " (Taylor 2 ( 0 0 ) .<br />

q Interview with Ridley 2 0 0 0 as reprinted in Wood s 2004: 183. Cf. an int erview<br />

with Joel Coen in Romn ey 200 0 as reprinted in Wood s 2 0 0 4 : 176.<br />

15 Pace Weinli ch 2 ()()5: lO T "The Coen brothers r ead Ody sseu s' fant astic adventures<br />

of Books 9- 12 pr agm atic ally , not symbolically." Although Weinli ch' s<br />

ess ay (r ead aft er I submitte d thi s ess ay for review) offe rs a worthy approach<br />

and rai ses important qu estions. we disagree on a number of important way s in<br />

which text and film int er sect.

o BROTHER. WI-JERE ART THOU? AND TJ-IEODYSSEY :!. /7<br />

pr -ison-s-a s provided by th e s he r-iff in two se pa rate meetings: "p r iso n<br />

farm 01' the pearly g

2/8 JANICE SIEGEL<br />

place is two weeks from everywhere" (OB 18). Like Odysseus. Everett<br />

leads his crew westwardly (10 .27 = OB 9) but doubles back on his own<br />

path (10 .59-6 I = OB 63) before eventually reaching home.<br />

In a comic rendering of the epic style. the heroes of 0 Brother<br />

Everett. Delmar and Pete-also represent the best qualities their culture<br />

ha s to offer. Although more than usually flawed and from the lowe st<br />

societal str atum . Everett and his buddies are noble in spir it. Like Ody sseu<br />

s. they show fierce loyalty to their own families and to each other<br />

(response to betrayal is a topos common to both text s). Everett's uncharacteristic<br />

prayer at the end of the film. when death seems ine scapable<br />

. even mirrors one made by Odysseus:<br />

"Roug h yeal's I'v e had : now ma y I see on ce more my halls. my land s.<br />

my peopl e before I die!" (Od. 7.240- 4 1)<br />

" I just want to see my dau ght er s again . Oh Lord. I've been separ ated<br />

from my famil y for so lon g ..; " (DB !(4)<br />

Petty crooks all (a comic downsizing of Ody sseus' piratical way s).<br />

Everett, Pete , and Delmar often find themselve s victims of their own<br />

appetites and knowingly do wrong. But they always find themselve s on<br />

the side of Good wh en they have to choose. They stand up against Evil<br />

even when it is unpopular and un safe to do so (e.g. bringing down th e<br />

local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan) and they ri sk their own live s to protect<br />

tho se who can't help themselve s (e.g. saving Tommy from being<br />

lynched. or fr eeing Pete from jail)." The Coens' comic vision also transforms<br />

every violent confr ontation in Homer's mod el text into a comic<br />

enterprise in 0 Brother.<br />

Thi s comic tendency is apparent in 0 Brothcrs transformation of<br />

Homer's epic hero. too . Odysseu s is the mod el of leadership Everett<br />

would like to be but con sistently falls shor t of. According to Fitzge rald's<br />

translation. Homer's Ody sseu s is "royal" (13.79), "mas ter of many<br />

crafts" (18 .452), and full of "sap." "prudence ." "foresight ." "wit." and<br />

"steadiness" (4.289-95). He is versatile (5.21 2). "canniest of men " (8. 160),<br />

and "sly and guileful" (14 .457) . 0 Brother's Ulysses Ever ett McGill fan <br />

cies him self a trickster and a wordsmith (OB 54) in the style of Ody sseus.<br />

But far from having achieved the success of an Ody sseu s. Ever ett<br />

is just a run-of-the-mill con man. and not a very good on e at that.<br />

In Fitzgerald's translation of th e Ody ssey. the most frequently used<br />

epithet for Ody sseu s is "the gr eat tactician." IH Earl y in the film, Evere tt<br />

I?Cf. Joel Coens comments in intervie w with Romn ey 2000 as reprinted in<br />

Wood s 20° 4: 179.<br />

IHE.g. 7.257.8-440,1 1.4 13, 11.438. 15-464. 17.18.17-455, 19.52. 19.579 , 23. 147 . and<br />

24.39 1.

o BROTHER. WH ERE ART THOU? AND TI-IEODYSSEY 2 19<br />

tacitl y compares himself to Odysseu s when he assures his compadres<br />

that "the '01 tactician's already got a plan" (OB (9) , Luter he acknowledges<br />

that he r eally "did n' t have no plan" (OB 33 ), But wh en th e tim e<br />

comes to convince the boy s that he is a worthy leader. Everett admits: "I<br />

know I've made some tacti cal mistakes .... And I've got a plan ... " (Of)<br />

89). But unlike Odysseu s. Everett suffers both Irorn a distinct lack of<br />

imagination and

JANICE SIEGEL<br />

is the undisputed Truth that the god s exist and that for good or for ill<br />

the y involve themselves in men 's live s." In 0 Brother, however, the<br />

characters spend a good deal of their time arguing whether God, the<br />

Devil , and other beings with super natural talents (w izar ds and seers ,<br />

for example) exist at all.<br />

It is generally part of the human condition to want to explain the inexplicable<br />

and to seek knowledge beyond our ken . In the Ody ssey , it is<br />

the god s who provide the an swers men seek. They communicate them<br />

to man through a variety of ways including dreams (e.g. 4.852ff., 19.620<br />

42), prophecy (e.g. Proteus in 4.501-3, Teiresias in II.I 12-5 2, and Theoklymenos<br />

in 17.20 I), bird auguries (e.g . 2.155- 63, 15.198-99, 15.636-4 6)<br />

and meteorological signs (e.g. 20.110-17 and 21.471-72).<br />

Man 's quest for knowledge drives the action in 0 Brother. too . The<br />

phrase "looking for an swers" haunts the film . Everett conjectures that<br />

"Looking for an swers" (OB 12) is the rea son Cora Hogwallop left her<br />

hu sband. He also note s that " Looking for an sw er s" is the rea son that<br />

Christianity is so popular (OB 23). Big Dan Teague, the larcenous Bible<br />

sales man, sees thi s as a weakness he is happy to exploit: "Folks'r e<br />

lookin' for an swers and Big Dan Teague sells the only book that's got<br />

'em!" (OB 54). Penn y take s a more practical approach. She plans to<br />

marry a man with "p r ospects " (OB7 2) becau se her children "look to me<br />

for an swers" (OB 72). Ever ett un succe ssfull y present s him self as the<br />

true an swer to Penny's prayers when he plaintively crie s to his estranged<br />

wife, " I' ve got the answers!"(OB 90).<br />

Pete and Delmar believe that God an sw er s prayers (e.g. OB 62 and<br />

OB 1(4). Everett, on the other hand, is a rationalizer, the only memb er<br />

of the group to remain spir itually "unaffiliated" (OB 27). He dismi sses<br />

belief in divinity as "r idiculous supers tition " (OB 25) and scoffs at supernatural<br />

explanations for natural phenomena (e.g. OB 9). For th eir<br />

faith, he dismisses his friends as "ignorant fools, " "hayseeds" and<br />

"durnbern a bag of hammers" (OB 25-6) . When Delmar delights that<br />

baptism has cleansed him of his sins and brought him salvation ("Neither<br />

God nor man 's got nothin' on me now," OB 24), Everett reminds<br />

him of the power of earthly law: "Even if it did put you squa re with the<br />

'lJOdysseus cr edit s "some god , invi sible " (10 .157) with stee r ing his ship to<br />

safety . He is gr atef ul th at du rin g a hunt "some go d's compass ion set a big buck<br />

in moti on to cr oss my path " (10 .173-74). Athe na se nds a w ind to tak e Telern achu<br />

s hom e ( 15.36 2). and as fath er and son pr epare to sla ug hter the suitor s.<br />

Telerna chu s not es th at "O ne of th e gods of heav en is in thi s plac e" ( 19.51) . In th e<br />

end , Athe na herself comma nds th e men of Ithaka to mak e peace (24 ,59 2-94), and<br />

her wo rd s are pun ctu at ed by Ze us "dr oplping ] a thunderbolt smoking at his<br />

dau ght er 's feet " (24.602 -3),

o BROTH ER. WH ERE A RT THOU ? AND T!-IE O DYSSEY 22 1<br />

Lord. th e State of Mississippi is more hardnosed " (D B 25). -''' And yet.<br />

Eve re tt and his fri end s enjoy th e benefits of success for' whi ch th er e is<br />

no a ppa re nt ea r thly explana tion.<br />

The most superna tura l of so urces for ans wers in 0 Brothe l' is. of<br />

co urse. th e blind railr oad man (OB 7-lJ). with whom th e film both ope ns<br />

and closes. With his oddly insightful prophecy. thi s character cha llenges<br />

Eve re tt's view of th e world ri ght Irorn th e stan of th e film :<br />

You see k a g l'eat fortune . yo u th ree wh o are now in chai ns ... And yo u<br />

w ill find a fortune-s-tho ug h it w ill not be th e fortune yo u see k . . But<br />

firs t. firs t yo u m ust tl 'avel- a lon g a nd diffic ult mad-a wad fra ug ht<br />

wi th per-il, un huh. a nd pregna nt w ith adventure . You s ha ll see things<br />

wonde rfu l to tell. Yo u sha ll see a cow on th e ro of of a cott o nho use . uh <br />

huh . and oh . so man y sta rtlem ent s .... I ca nnot say how lon g thi s mad<br />

s ha ll be. But fear not th e obsta cles in yow ' path. for Fate has vo uchsa<br />

fed yo uI ' rewrud. And th ou gh th e r oad may wi nd, a nd yea . yo ul'<br />

hearts gl'ow weal 'Y. still s ha ll ye Ioller th e way . eve n unt o ylll ll' sa lva <br />

tio n ... . lzzat clear?' (OB8-tj)<br />

Thi s speec h is design ed to fulfill th e sa me purpose as th e on e Teiresias<br />

(the Odyssey's blind see r) gives Odysseus in th e Und erworld." Both<br />

detail a parti cularly odd p rophecy th at will come to pass (cow on th e<br />

r oof of a cotto nho use :::: people mistaking an oar for a winn owing fan ).<br />

And both sha re detail s of the her o's future th at turn o ut to be t ru e.<br />

Del ma r and Pete are aw ed th at th e see r seems to know th at th ey see k<br />

th e sec re t treasure Eve re tt told th em he buried befo re bein g incarcer <br />

at ed. but dism ayed to hea l' that th ey are not destin ed to find it. Everett<br />

is mom entaril y spo oked th at th e seer would eve n kn ow abo ut thi s<br />

tr ea su r e. since it was a lie fa b r-ica te d to convi nce Pete a nd Delma r to<br />

cooperate in th e jailbreak.<br />

Never the less. Eve re tt is able to rej ect belief in superstition for' his<br />

ve rs ion of science/ rationalit y. He cava lierly di smi sses th e un canny<br />

abilities of thi s "ignor ant old man " (D B (0 ) as th e kind of "para-nor mal<br />

psych ic pow ers" acquire d by th e blind in compe nsa tion for' th eir loss of<br />

sig ht (DB lJ). His immed iate goa l. of co ur se. is to disp el Pete and Del-<br />

.'' In th e so undtrac k liner not es to th e DVD version of 0 Bro th er, th e "blissf ul<br />

Baptis t congregation engaged in riv erside imm ersion " is eq ua ted with "the Lotu<br />

s-Eater s Itj.tj8- 102] w ho lull Ulysses' cohorts." Equa ting th e cons um ptio n of a<br />

na rc oti c-lik e plant w ith baptism to fulfill hop e of sa lva tio n is indee d . as Da ne k<br />

200 I : 87 suggests. a new tw ist on the idea of "I'eligion as th e opi um of the peo <br />

pie." Flensted-jense n 2()()2: 18 concurs : " Delma r and Pete are dl·ugge d . not by a<br />

fr uit. but by reli gion ."<br />

.' 1 For a co m parison of the two pro ph ecies . see Flensted-je nse n. 2002: 18 a nd<br />

Heckel 2oo5 b: 58. See Werne r 2003: 175 fOf' th e sim ilar ity of th eir archa ic a nd<br />

poeti c speec h pa tte rn s.

JANICE SIEGEL<br />

mar's doubts. But the scene has programmatic importance as well. Thi s<br />

is just the fir st of many conflicts between Pete and Delmar, who believ e<br />

in the super natur al and divine. and Everett, who trusts in the ability of<br />

man-and particularly in him self-to make his own wa y in the world.<br />

Over and over in the film. Everett's vision of the world will be forc efully<br />

challenged by the characters he meet s and the difficulties he faces<br />

(beginning with the Sirens, the fir st of th e Od yssean adventures). Although<br />

it might see m to us that Everett. like Odysseu s, enjoy s some sor t<br />

of divine guardianship that also extends to his companions. Everett will<br />

to the end see success as his reward for keeping faith in himself.<br />

THE SIR ENS<br />

In Fitzgerald's translation of the Odyssey. the Sirens lure their victims<br />

with their seductive song, "crying beauty to bewitch men coasting by "<br />

(12.48-49). Odysseu s de scribes their song as "ha unting " (12.19 I) . The<br />

singing of the Sir en s in 0 Brother is de scribed as "barely humon" (set<br />

directions. OB 47) and" unearthly " (set directions, OB 48) . In the "Po stscri<br />

pt" to his translation. the one acknowledged as a sour ce by the<br />

Coen s, Fitzgerald describes the "conjur ing kind of echolalia " of th e sirens'<br />

song in Greek. and how "the crooning vowels are for low sed uctiv<br />

e voice s ... " (Fitzg erald 1962 [1998J : 493). The haunting song of the<br />

film 's sirens is true to the se very qualities.<br />

In the Ody ssey. Od ysseu s him self explains how much he wanted to<br />

hear th e sirens ' song ( 12.246- 47). But Cir ce encouraged him to have his<br />

crew lash him to th e mast so that he could listen in safety. "Shout as you<br />

will " (12.65). she warned. the crew mu st "kee p their str oke up . till th e<br />

singers fade " (12.67). In 0 Brother. Pete is th e fir st to hear the song of<br />

the sire ns, and he scre a ms "PULL OYER!" (OB 48). Bereft of any overt<br />

divine guidance. Everett scratches his head and wonders aloud. "I gue ss<br />

or Pete 's got the itch " (OB 48) as he pulls the car over and Pete rac es<br />

through the wood s ahead of his friends.<br />

The sour ce of th e singing in 0 Brother is a trio of women described<br />

as "beautiful but marked by an otherworldly lsngot" (OB 48). The y<br />

stand upon a tongue of ro ck that jut s into the river as they wa sh clothes<br />

in the water. Seductively drenched. th ese three river sir en s. as if<br />

anonymous forc es of nature. ignore th e boy s' attempts to engage th em<br />

in conver sation and intoxicate them with their presence. thei r song. and<br />

their corn liquor. And wh en Everett and Delmar awaken from their<br />

debauch. they find Pete missing. A ser ies of set directions explains how<br />

Delmar come s to the dramatic conclusion that Pete has been transformed<br />

into a toad:<br />

Pete 's cloth es ar e laid out on th e g round. not ill a heap . but mimickin g

224 JANICE SIEGEL<br />

THE CY CLOP S<br />

At this restaurant (decorated with a bust of Homer), Everett and Delmar<br />

meet the film 's Cyclops character, the one-eyed Big Dan Teague.<br />

Homer's Polyphemus is a monster who is also a shepherd. Big Dan is a<br />

shepherd of sor ts (a Bible sales man intent on fleecing his flock) who is<br />

really a monster. Like Polyphemus. Big Dan is physically imposing: set<br />

de scriptions call him "br oad-shoulder ed" (OB 53) and "a big man" (OB<br />

54). Like the isolated Cyclops, who live s alone in his cave (9.202), Big<br />

Dan sit s alone at his table (OB 53). In each tale. initial contact between<br />

the Cyclops figure and his victims establishe s the monster's home field<br />

advantage: Big Dan 's "Don' t believe I've seen you boy s around here before<br />

.. ." (OB 54) is equivalent to the Cyclops' "' Str a ngers .. . who are<br />

you? And where from?" (9.274). In both texts. the greed of each hero<br />

lead s to his downfall. Odysseu s wants the Cyclops ' fat sheep. lambs and<br />

kid s. and stor es of chee se (9.233-36) plu s whatever else he might have to<br />

offer (9.249). Evere tt and Delmar are interested in Big Dan's promise of<br />

"the vast amounts of money [to] be made in the ser vice of God Amighty<br />

Isid " (OB 55)·<br />

At Big Dan 's sug gestion. the group relocates to "more private environs"<br />

(OB 55) out in the country. The Cyclop s. too. prefers to graze his<br />

flock "r emote from all companions" (9.2° 3). A trick camera angle cau ses<br />

the hulking figure of Big Dan. now sitting alone in the foreground. to<br />

appear so large that he dwarfs the mas sive tree behind him . Thi s shot<br />

evokes the Cyclops as de scribed by Odysseu s. "a brute so huge. he<br />

seemed no man at all of those who eat good wheaten bread; but he<br />

seemed rather a shaggy mountain reared in solitude " (9.2° 3-7).<br />

In each Cyclops scene. the monster enjoys a meal of meat provided<br />

by his victims. Homer's Cyclops "dismember ed [th e men] and made his<br />

meal. gaping and cr unching like a mountain lion-everything: innards.<br />

flesh. and marrow bones" (9.313-18). Similarly. Big Dan. a selfproclaimed<br />

"man of large appetites" (OB 57), attacks his meal of chicken<br />

frica ssee. a recipe that specifically includes skin. flesh . and bones (a meal<br />

for which Everett paid). Eve n his disgu sting eating habits re sonate with<br />

those of the Cy clops:<br />

Dru nk. hiccupping. [th e Cyclops ] dribbled streams of liquor and bit s of<br />

men (9-404 -5)<br />

Big Dan is just sucking the last pi ece of chicke n offa bone . He tosses the<br />

bon e over his shoulder . belch es. and sighs (set direction s. OB 57). (In<br />

th e film . an op en bottle of beer indicates that he ha s been drinking.<br />

too.)<br />

Even before Odysseu s meet s the Cy clops . he senses trouble: "for in my<br />

bones I knew some towering brute would be upon us soon- all outward

o BROTH ER. WH ER E ART THOU? AND TJ-IE ODYSS EY 2 25<br />

powel',

226 JANICE SIEGEL<br />

cess of the frog. weeping" (OB 60) .<br />

REUNION<br />

Eve ntually. both her oes ret urn hom e safe ly to th eir Ithak a, having escape<br />

d fro m so me kind of im p r isonment. In the Ody ssey th is occurs<br />

th r ough divine fiat (Zeu s orders Ca lyp so to release Ody sseu s. 5 .118<br />

12 1), while in 0 Brothel' the def ining factor is the will of Everett (w ho<br />

"just hadda bust out" of Parchma n' s Far m. OB 8 1). Each hero is driven<br />

to prevent his wife 's imp ending mar ri age to anot her man . Od ysse us<br />

learn s of his wif e's p redicam ent fro m Teiresias in the un der worl d<br />

(11.1 3 1). Everett receives a letter fro m Pen ny in th e mail (OB 81).<br />

Upo n th eir lon g-aw ait ed hom ecom ing . both her oes meet th eir<br />

childtren) befor e meetin g their spouse. Ody sseus. disgu ised as a beggar.<br />

at first present s him self as a stranger to his ow n son Telernac hus. w ho m<br />

he meets at Eurnaios ' hu t." The n Athe na allow s Telernachu s to see the<br />

tru e Od ysseu s. who embraces his child wit h fatherly affec tio n ( 16.223<br />

24). But star tled by this beggar's mira culous cha nge of appearance.<br />

Telema chu s rejects him : "You cannot be my father Od ysseus!" ( 16.228 <br />

29). Od ysseu s r espo nd s:<br />

"This is not pri ncely. to be swept<br />

Away by wonder tit yo ur fat her 's pI'esence.<br />

No ot her Odyss eus wi ll eve r com e,<br />

For he and I tire one. the sa me: his bitt er<br />

For tune and his wanderings tire mi ne.<br />

Tw ent y yetll's gone, and I tim back agai n<br />

On my ow n island . (16.238- 44)<br />

Only after Od ysseus exp lain s At hena 's divi ne intervent ion do fat her<br />

and son have their long-awaited . and ver y emotiona l. reunio n ( 16.253<br />

6n), Telernachus is de lig hted to welco me the her oic Odysseu s. the honored<br />

fathe r the son was taught would one day ret ur n to his everfaithful<br />

Penelope. Everet t is just as happy as Ody sseu s to see his chil-<br />

260 dysseus' r eun ion with his swine-herd Eurn a ios re tlp petlrs in inver se allusions<br />

wh en th e bo ys visit Pete's cous in Wash Hogw allop. Whe n fir st tlppreached<br />

. Wash is dest ru ctively whittling a piece of wood down to a nub with<br />

his kni fe: Eumaios is ca re fully cutt ing sa ndals from oxhid e (14.26- 27). Both<br />

farmers provide Friendly accom modation to th e tra velers : Wash Hogwallop 's<br />

eve ntua l betrayal contras rs wit h Eu maios' s steadfast loya lty . Delmar saves a<br />

piglet Iro m th e bur ning bam and returns it to the boy who r escu es them wh ile<br />

Ody sseu s ear s "the young porker s " (14.91) sla ughte re d for' his dinner. For' fUI'th<br />

er com par ison of Eumaios and Hogwa llop . see Dan ek 200 1: 86: Wer -ner 2003:<br />

176: Heckel 2()()5t1: 582: and Heckel 2Oo5b: 58. For' this peacef ul int erl ude as corres<br />

ponding to Ody sse us' respit e in Scheri a . see Weinli ch 2()()5: 92 a nd Heckel<br />

2()()5t1: 582.

o BROTH ER. WH ERE A RT THOU ? AND Tf-IE O DYSSEY 2 27<br />

d ren , and he comes by his beggars look s hon estl y, Despite th e sig ht before<br />

th eir eyes . th ou gh . his girl s too ha ve ca use to distrust th at th e man<br />

standing in front of th em is th eir lather retu rn ed home afte r a lon g abse<br />

nce:<br />

YOUNC EST<br />

Dad dy!<br />

MID DLE<br />

/-Ie ai n 't O UI' daddy!<br />

EVERETf<br />

Hell l ain 't ! Wha tsis ' Whnrvey' ga ls? - Your nam e's McC ill!<br />

YOUNC EST<br />

No sir! N ot since yo u got hit by a train!<br />

EVEREH<br />

Wh atre you talking a bo ut - I wasn 't hit by a t rain !<br />

M IDDL E<br />

Ma ma sa id you wa s hit by a train!<br />

YOUNCEST<br />

Blooey !<br />

OLDEST<br />

No thinJefrl<br />

MI!)DLE<br />

Ju st a g rease spot on th e L&N!<br />

EVERETT<br />

Da rnnit . I neve r bee n hit by a ny tra in! (aU ( 7)<br />

In The Odyssey . Telernach us has been prep ared for his Iarhers retur<br />

n. In 0 Bro the r . Eve re tts dau ght ers ha ve been told that he wi ll not<br />

be r etu rning . hen ce rheir conf usio n, The di fferen ce is du e not only to<br />

th e shift in th e characte r of th e epic hero . bu t also to th at of th e epic<br />

hero's spouse, In 0 Brother . Penn y "tur ns out not to be th e embodime nt<br />

of wifely constancy Homer rhapsodi zed " (Scott 2 ( 0 0 ) , She not onl y divo<br />

rced her hu sband "Ir orn sha me " (OfJ 7 1) while he was incar ce rat ed.<br />

but she th en lied to her child re n about his untimely death , In thi s way.<br />

Evere tt . just like Odysseus. ca n be sa id to ha ve retu rn ed fr om th e dead ,<br />

Evere tts dau ghter s th en tell him abo ut their mo th ers new beau .<br />

wh o is set to repl ace him , And just like Od ysse us. Eve r ett sets his children<br />

straig ht about how he is th eir only t ru e fath er:<br />

M II)J) LE<br />

He's a suitor!<br />

EVERET I'<br />

I-Im, What's his nam e?<br />

M IDD LE<br />

Vernon T, Wa ldrip.<br />

YO NCEST

22 8 JANICE SIEGEL<br />

Uncle Vernon.<br />

O LDEST<br />

Till tom or row.<br />

YO UNGEST<br />

The n he's gonna be Daddy!<br />

EVERETT<br />

I' m th e only daddy you go t! I' m th e da mn paterfamilias! (OB 68- 9)<br />

Similarly. Telem achu s inform s his own father about the rece nt eve nts<br />

conce r ning his moth er and her suitors (16.285-3°4). Odysseus ass ures<br />

him of the di vine assista nce th ey will receive ( 16.3°9) wh en it comes<br />

time to put his plan in motion . But Everett lacks both Od ysseu s' patien<br />

ce and his confidence in di vin e int er venti on . An gr y and w ith out a<br />

plan . he fooli shl y decid es to confront his wife, Penny. and her fian ce.<br />

Ver no n T. Wald rip.<br />

Horner 's Pen elop e is "tall in her beaut y as Ar temis or pale-gold<br />

Aphrodite" (17.45) . She is wise (e.g. 17.45 . 17.739 , 19.682) and tend er<br />

(17.512). We see her weep (e.g. 4.756.4.77°. 21.59-60. 23.34) and we hea r<br />

her lau gh (17 .710) . She lives in a palace with a staff of servants and<br />

herd s of livest ock to live off in th e extende d absence of her hu sban d<br />

C'no t twent y heroes in th e wh ole world wer e as r ich as he," 14.119-120).<br />

Whe n Penelope fina lly comes to und er stand th at Ody sse us has retu rn ed<br />

to her . she welcom es him with joy (23.23° -34).<br />

Penny McGill . wh en we fin ally meet her in Woo lworth's . is described<br />

as "a woman in her thirties with a haggard. careworn face" (OB<br />

70) . She is clearl y exha usted by th e dem and s of par enting seve n children.<br />

She is smart in a ha rd-as-nails kind of way. with out th e luxu r y of<br />

feelin g sorry for her self . (She won 't eve n smile until she is back on<br />

Everett's ar m at the end of th e film . and eve n th en her joy will easily<br />

turn to "indigna tion," OB 109 .) Penny need s a hu sband to p rovide for<br />

her family in hard eco no mic tim es. But wh en Everett r eturns. she disavo<br />

ws him : "He 's not my hu sband. Just a drifter . I g uess ... Just some<br />

no-account drifter ... " (OB 72). Ver no n T. Waldrip see ms the bett er<br />

catch by far : "Verno n her e's got a job. Ver no n's got prosp ects. He's<br />

bona fide ! Wh at' re you?" (OB7 2).<br />

Early in th e Ody ssey. the mature Telemac h us. no lon ger th e bab e<br />

Odysseus left "still cradled at [Pen elop e's] breast" ( 11.524) . qu esti ons his<br />

ow n paternity out of self-pity (I .260), not fro m any rea l concern th at he<br />

is not Odysseus' son (p hysica l resemblance mark s him as suc h th r ough <br />

out th e poem )." But the paterni ty of th e bab y Penny hold s to her breast<br />

is very ques tio na ble ind eed. Like his other child re n now divor ced fro m<br />

27 Weinlich (200 5: 1( 1) ast utely observes th at in contrast. th e girls' adoption<br />

of the ir moth er 's lan guage and voice shows their ide ntifica tio n wit h her.

o BROTH ER, WI-IERE ART THOU? AND Tf-IEODYSSEY 229<br />

him. the baby (a str anger to Everett) doe sn't even ca r r y his name ( 013<br />

70). Thi s insult of eras ed pat ernity is more than Evere tt can bear.<br />

FIST FICH T<br />

A sce ne of confrontation between riv als then OCCUI ' S in both text s. again<br />

with comic defusement in 0 Brothel'. When Eve re tt calls Penny a " Iyiu'<br />

. un con stant succubus," Waldrip call s him out on his manner s:<br />

WALDRII' : You ca n' t swea r' at my fian cee!<br />

EVE RETT : O h yea h? Well you ca n't mal'I 'y my wife! (08 72).<br />

Vernon T. Waldrip's tr espasses-using Ever ett's hair treatment and<br />

planning to become head of his hou sehold-are the comic eq uivalent of<br />

th e cr imes committed by the suitors . as described by Teiresia s (11.130<br />

3 I) : "insolent men eating your livesto ck as th ey cour t YOUI' lady."<br />

Werner (200]: 184) notes that in his arrogance, Waldrip even reminds<br />

us specifically of Antinoos. Inevitably, a violent clash between hu sband<br />

and suitorts) occurs in both text s. But th e details of thi s fight between<br />

Eve re tt and Waldrip are tak en from a scene that precedes Odysseu s'<br />

slaug hte r of his wif e' s suitors. the fistfight between rival beggars Od ysse<br />

us and lros (d. Dan ek 200 I : 86 and Heckel 2ooSb: 60). In both texts, a<br />

crowd gathers to watch the fight. In 0 Brother. Ever et t fail s to land a<br />

single blow. And de spite being used as a punching bag. he sheds not on e<br />

drop of blood:<br />

[Everett] tak es a wild s wing whi ch Waldrip easily dudes. Waldrip<br />

adop ts a Marquess of Oue cnsbur y stance and prances about. deli vering<br />

sting ing punches to th e nose of a stunned and outclassed Evere tt (0 8<br />

72 ) .<br />

In th e Odyssey. Od ysseu s mangles lros with just on e punch. Afte r his<br />

def eat. lro s is unc er emoniously ejected Irorn th e premi ses:<br />

Now both conte nde rs<br />

put th eir hands up .<br />

Th e two<br />

were at close qu arters now. a nd lro s lun ged<br />

hitt ing th e sho ulde r. Th en Odysseus ho ok ed him<br />

und er th e ea r and shatte re d his jaw bon e.<br />

so bri ght r ed blood ca me bubbling fr-om his mouth.<br />

as down he pit ched into th e du st . bleating.<br />

kickin g aga ins t the g ro und. his teeth stove d in . ( II' . J()1'- 9: 115-1 21)<br />

The n. by th e a nkle bon e.<br />

Odysseus hauled th e fallen on e out sid e.<br />

crossing th e cour tya rd to th e ga te . a nd piled him<br />

against th e wall. In his ri ght had he st uck<br />

his beggin g sta ff and said: "Hcrc tak e your' post.<br />

Sit here to keep th e do gs a nd pigs away .. . ( 11'. 123- 30 )

23°<br />

JANICE SIEGEL<br />

In 0 Brother. it is Everett-clearly a lover. not a fighter-who suffers<br />

the indignity of defeat and expulsion:<br />

EXT. WOOLWORTH's<br />

Its glass doors swing op en and Everett is hurled out and beJJyflops into the<br />

dust of the street.<br />

BRAWNY MANAGER:<br />

... And stay out of Woolworth's! (OB72- 3)<br />

CINEMA SCEN E AS KATAB ASIS<br />

Everett and Delmar then retreat to the local cinema and perform a kind<br />

of styli zed kataba sis from which they emerge with crucial information<br />

that will affect their future." The theater and the underworld are alike<br />

in that they both lie beyond the reach of the sun." In both text s. the he ro<br />

positions himself fir st. and then a throng appears. When the prisoners<br />

from Parchman's Farm are ushered into the theater. the leaking daylight<br />

that illuminates their pas sage gives them a fluttery. less than substantial.<br />

appearance similar to that of the shades in Hades (d. Content<br />

200 1: 45). The shade of Ody sseu s' dead mother. for example, Odysseu s<br />

describes as "impalpable as shadows are, and wavering like a dream"<br />

(11.231- 32).<br />

Both Ody sseu s and Ever ett are sur p rised to meet a lost comrade.<br />

Everett stares at Pete "As if at a ghost " (OB 75). Ody sseu s de scribes the<br />

shade of Elpenor as a "faint image of the lad " (11.93): he is a "ghost "<br />

(11.97). Rather than a pool of blood, it is a few rows of empty seats in<br />

the movie theater that separ ate Everett and Delmar from their recently<br />

departed fri end and his new associates. Pete's harshly whi spered warning-"Do<br />

not see k the treasure! It' s a bushwhack" (OB 74)-corresponds<br />

to Elpenors similarl y dire warning to Ody sseu s: "Do not abandon<br />

me unwept. unburied. to tempt the god s' wrath" (11.81- 2). The<br />

authority feared in 0 Brother. though, is human. not divine.<br />

And only in 0 Broth er do we find the add ed dimension of humor.<br />

wh en Delmar tri es to explain their sur prise and delight at being r eunit<br />

ed with Pete: "We thought you wa s a toad!" (OB 75). Despite Delmar's<br />

lack of discr etion-his repeated stage whi spering and bod y language<br />

are anything but subtle- the other prisoners act as if the y simply<br />

don 't hear anything. Neither do th e shades in Hades interact in any way<br />

with Od ysseu s unl ess they are invited (11.164- 67). Ody sseu s cuts his<br />

oRFOI' th e pattern of kataba sis in a ncient literatur- e and its ada pta tion in mod <br />

er n film, see Holt smark 200 I : 23-5 0 , esp. 25- 27. Heckel (zonga : 585 ) also equates<br />

thi s scene with Odysseus ' nekyio .<br />

2

o BROTHER. WH ERE ART THOU? AND T!-IEODYSS EY 23 /<br />

time in Hades sho r t for fear of "the gods below" (1 1-49). Delmar and<br />

Eve r ett fear the prison guards. a mortal set of overseers who can heal'<br />

them and are sim ila r ly re sponsibl e for imprisonment and punishment.<br />

And thi s is con sistent with the re st of the film. where the powerful figures<br />

that aff ect our heroes are not gods but god-lik e mortals: Horner<br />

Stokes. Menelaus " Pa ppy " O'Daniel, and She r-iff Cooley . all of whom<br />

manipulate and exploit human beings in th eir own battle for power."'<br />

Another link between thi s movie-theater scene and Book 1 I of th e<br />

Ody ssey is that each features a hero's expression of distrust toward<br />

women in general because of his wife's personal betrayal. Th e diatrib e<br />

against women delivered by Agamemnon is adapted and rei ssu ed here<br />

by the wounded Everett . :1' Agamemnon exp la ins how he was murdered<br />

by his own wif e Clytemnestra upon hi s homecoming: "But that woman.<br />

plotting a thing so low. defiled herself and all her se x. all women ye t to<br />

co me . ev en those few who may be virtuous " (11. 501 - 4). Agamemnon<br />

hopes that hi s words of advice will sav e Odysseu s. "L et it be a warning<br />

ev en to you" (11. 5 14-15): "The day of faithful wives is gone Iorever"<br />

(11. 534).<br />

An angry Eve re tt feel s sim ila r ly betrayed by his wife Penny: "Dece<br />

itful! Tw o-faced ! She- w o ma n! Never trust a female. Delmar! Rem ember<br />

that on e simple precept and your tim e with me will not have been ill<br />

spent! ... Hit by a train! Truth means nothin' to Woman. Delmar" (OB<br />

73).:12 We have se en how Penny is no Penelope. But neither is she a<br />

vengeful Clyte m nes tra . de spite the metaphori cal killing off of her hu sband<br />

(in both cas es per -petrated for th e ost en sibl e good of th e family at<br />

large) . And Eve rett will eve ntually win the pea ceful r eunion with his<br />

wif e that wa s deni ed to Aga me m no n.<br />

K u K LUX KL A N RA LLY AS D EFEA T O F TIIE C YCLO PS<br />

It should come

o BROTH ER. WH ERE ART THOU? A N D Tf-IE ODY SSEY 233<br />

But although dela yed due to the vagaries of th e plot. thi s scene in th e<br />

film depicts the vanquishing of the Cyclops (with whom the y are reunit<br />

ed at last )." Both sets of heroes find a wa y to rem ain invi sible in th e<br />

presen ce of the en em y, Ody sse us and his men lash th em selve s und er th e<br />