CAD/CAM Technology and Zirconium Oxide with Feather-edge ...

CAD/CAM Technology and Zirconium Oxide with Feather-edge ...

CAD/CAM Technology and Zirconium Oxide with Feather-edge ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

2<br />

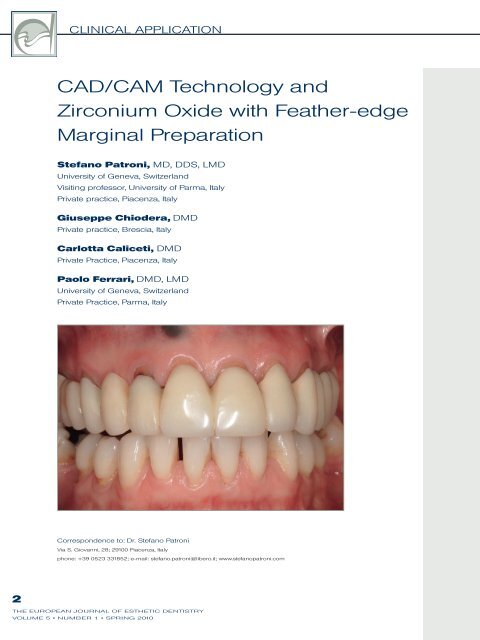

CLINICAL APPLICATION<br />

<strong>CAD</strong>/<strong>CAM</strong> <strong>Technology</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Zirconium</strong> <strong>Oxide</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Feather</strong>-<strong>edge</strong><br />

Marginal Preparation<br />

Stefano Patroni, MD, DDS, LMD<br />

University of Geneva, Switzerl<strong>and</strong><br />

Visiting professor, University of Parma, Italy<br />

Private practice, Piacenza, Italy<br />

Giuseppe Chiodera, DMD<br />

Private practice, Brescia, Italy<br />

Carlotta Caliceti, DMD<br />

Private Practice, Piacenza, Italy<br />

Paolo Ferrari, DMD, LMD<br />

University of Geneva, Switzerl<strong>and</strong><br />

Private Practice, Parma, Italy<br />

Correspondence to: Dr. Stefano Patroni<br />

Via S. Giovanni, 28; 29100 Piacenza, Italy<br />

phone: +39 0523 331852; e-mail: stefano.patroni@libero.it; www.stefanopatroni.com<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010

Abstract<br />

Clinical needs <strong>and</strong> growing patient expectations<br />

have forced modern dentistry to focus<br />

on finding ever simpler protocols <strong>and</strong><br />

to develop materials which offer high performance<br />

in their mechanical resistance<br />

<strong>and</strong> esthetics.<br />

In recent years, the scientific community<br />

has been venturing into the world of<br />

<strong>CAD</strong>/<strong>CAM</strong>, a significant technological innovation<br />

imported from the world of engineering.<br />

This innovation has made it<br />

possible to exploit a material which has<br />

long been noted for its mechanical <strong>and</strong><br />

mimetic qualities: zirconium oxide. While<br />

<strong>CAD</strong>/<strong>CAM</strong> is revolutionizing the laboratory<br />

work of dental technicians, the white color<br />

of zirconium has opened new avenues<br />

PATRONI<br />

which may lead not only to new options<br />

for proper treatment planning, but also to<br />

new opportunities in the choice of materials<br />

to be used in prosthetic rehabilitation<br />

<strong>and</strong> variation of the types of preparations<br />

possible.<br />

The present paper will analyze the advantages<br />

<strong>and</strong> limitations of these methodologies,<br />

which are capable of simplifying<br />

clinical protocols <strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ardizing results.<br />

These technologies have instilled<br />

great enthusiasm in the profession due to<br />

their innovative nature, but this approach<br />

needs to be verified by further scientific<br />

evidence.<br />

(Eur J Esthet Dent 2010;5:XXX–XXX)<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010<br />

3

4<br />

CLINICAL APPLICATION<br />

Introduction<br />

<strong>CAD</strong>/<strong>CAM</strong> is a term borrowed, like the<br />

technology associated <strong>with</strong> it, from the<br />

world of engineering <strong>and</strong> has been applied<br />

to clinical dentistry. The end products<br />

in the two fields are very different as far as<br />

materials, forms, <strong>and</strong> dimensions are concerned,<br />

but the philosophy behind the<br />

process remains the same <strong>and</strong> involves<br />

the replacement of manpower <strong>with</strong> mechanized<br />

or robot-powered procedures. 1,2<br />

The procedures can be divided in two<br />

phases: <strong>CAD</strong> (computer-aided design),<br />

whereby the object is designed <strong>and</strong> created<br />

virtually, <strong>and</strong> <strong>CAM</strong> (computer-aided<br />

manufacturing) which takes the design<br />

from the virtual to the production of the designed<br />

object.<br />

The precision involved <strong>and</strong> the ability of<br />

this technology to st<strong>and</strong>ardize both the<br />

process <strong>and</strong> the finished product make its<br />

potential fascinating in itself; in theory it<br />

may even be possible to eliminate variables<br />

introduced by the operator in the laboratory<br />

phase <strong>and</strong> reduce the clinical steps<br />

needed to produce the final prosthesis. 3 Interest<br />

for <strong>CAD</strong>/<strong>CAM</strong> technology has been<br />

expressed by dentists the world over, as<br />

this technology makes it possible to work<br />

<strong>with</strong> different materials. Some of these include<br />

titanium as base metal alloys, acrylic<br />

resins for provisional restorations, <strong>and</strong> either<br />

crystalline or vitreous ceramics. The<br />

material <strong>with</strong> the most applications is a ceramic<br />

oxide stabilized <strong>with</strong> yttrium oxide<br />

known as zirconium dioxide (zirconia). 4<br />

Many questions have arisen about this<br />

new method from both clinicians <strong>and</strong> dental<br />

technicians alike; in fact, the laboratory<br />

will be most affected by these innovations.<br />

Therefore, the clinician needs to be able<br />

to underst<strong>and</strong> how these new <strong>CAD</strong>/<strong>CAM</strong><br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010<br />

technologies <strong>and</strong> intraoral optical impressions<br />

can be integrated <strong>with</strong> everyday clinical<br />

practice, what type of preparations <strong>and</strong><br />

prosthetic margins will be compatible <strong>with</strong><br />

these new materials, <strong>and</strong> precise information<br />

about how to use them.<br />

From a chemical point of view, zirconium<br />

is a grey/white hard transition metal,<br />

which is not found in nature as a pure mineral.<br />

In dentistry, zirconium is not used as a<br />

pure mineral but as a ceramic oxide (zirconium<br />

dioxide) instead. From a structural<br />

point of view, zirconium dioxide comes in<br />

three states: cubic, monocline, <strong>and</strong> tetragonal.<br />

5 All of these states are unstable at<br />

room temperature <strong>and</strong> must be combined<br />

<strong>with</strong> an element to hold the desired form.<br />

The tetragonal is one of the most studied<br />

forms in published literature 6 <strong>and</strong> is stabilized<br />

<strong>with</strong> yttrium. 7 This material was used<br />

experimentally as early as 1969 in the field<br />

of orthopedics.<br />

It is the esthetic <strong>and</strong> mechanical characteristics<br />

of zirconium which makes it such<br />

an attractive metal to work <strong>with</strong>. Indeed, not<br />

only is it white in color, but its resistance to<br />

fractures is very similar to that of titanium<br />

(285 N vs 305 N). 8 In addition, it is not cytotoxic,<br />

9 does not produce mutations of the<br />

cellular genome, 8,10 <strong>and</strong> it induces a modest<br />

inflammatory response in tissues, which<br />

is less than that of titanium. 11<br />

Another attractive characteristic of the<br />

material is that it has little retention of bacterial<br />

plaque. Scarano reported a bacterial<br />

covering on the surface of zirconium of<br />

12%, as opposed to 19% for titanium. 5<br />

<strong>Zirconium</strong> has multiple applications in<br />

dentistry. It can be used as a core for onlays/overlays,<br />

as a core for single crowns,<br />

as a framework for bridges, as abutments<br />

for implants (Fig 1), <strong>and</strong> as implants themselves.

Despite the material having been well<br />

known, the technology was not available.<br />

Today, thanks to <strong>CAD</strong>/<strong>CAM</strong>, this technological<br />

gap has been filled.<br />

The structures are obtained by subtraction<br />

milling a partially sintered zirconium<br />

block; this procedure is guided by dedicated<br />

software. 12<br />

An overview of zirconium<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>CAD</strong>/<strong>CAM</strong><br />

It must be borne in mind that the zirconium<br />

structure is no longer made by a technician<br />

but by the milling center machine which<br />

grinds the zirconium block. This requires<br />

specific instructions <strong>and</strong> guidelines in digital<br />

form, which can be summarized in<br />

three steps: 3<br />

1) digitization: transforms the geometry of<br />

the scanned object into digital data<br />

2) processing: software processes the data<br />

<strong>and</strong>, if necessary, develops the project<br />

3) realization: technology (not necessarily<br />

a milling machine) transforms the data<br />

into the desired object.<br />

When using <strong>CAM</strong>/<strong>CAD</strong> technology, the<br />

classic clinical/technical itinerary (impression,<br />

model, waxup, casting) must interface<br />

<strong>with</strong> the digital pathway (Table 1). The<br />

transformation of analog information into<br />

digital information can take place at various<br />

points in the conventional process:<br />

1) The impression is developed in the laboratory.<br />

The laboratory forwards the<br />

model to the digital service who will<br />

digitize it, design the structure (<strong>CAD</strong>),<br />

realize it (<strong>CAM</strong>), <strong>and</strong> then send it back<br />

to the technician for ceramic stratification<br />

(Table 2).<br />

PATRONI<br />

Fig 1 Example of a custom implant abutment completely<br />

realized in zirconia.<br />

Table 1<br />

Table 2<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010<br />

5

6<br />

CLINICAL APPLICATION<br />

Table 3a<br />

Table 3b<br />

Table 4<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010<br />

2) The impression is developed in the laboratory.<br />

The technician digitizes the<br />

model <strong>with</strong> a scanner <strong>and</strong> <strong>with</strong> special<br />

software designs the structure (<strong>CAD</strong>)<br />

(Table 3a). Alternatively, the technician<br />

can realize a traditional waxup <strong>and</strong> scan<br />

it (Table 3b). In both cases, the laboratory<br />

will be able to issue a digital file to the<br />

milling center for manufacturing the<br />

structure (<strong>CAM</strong>). The structure is then<br />

sent back to the laboratory for ceramic<br />

stratification .<br />

3) The impression can take the digital route<br />

from its beginning (eg, using a 3M ESPE<br />

video camera or similar). The planning<br />

can take place either in the laboratory or<br />

in the digital service center (<strong>CAD</strong>). However,<br />

the manufacture of the core (<strong>CAM</strong>),<br />

must take place in the milling center <strong>and</strong><br />

is then delivered to the laboratory along<br />

<strong>with</strong> a resin model for ceramic stratification<br />

(Table 4).<br />

In the authors' clinical experience, the<br />

method that gives the best frameworks/<br />

cores for supporting ceramics is that<br />

which starts <strong>with</strong> a conventional waxup of<br />

the structure made in the laboratory which<br />

is then scanned. This technique allows the<br />

creation of an individualized structure,<br />

which means that the design can be customized<br />

<strong>with</strong> an adequate cusp <strong>and</strong> marginal<br />

crest. This creates, where necessary,<br />

a palatine framework thickening <strong>and</strong> adequate<br />

connection design (Fig 2a <strong>and</strong> b).

a b<br />

Clinical application<br />

For a fixed prosthesis, the base material of<br />

the ceramic crown which is most commonly<br />

used <strong>and</strong> which, according to scientific<br />

evidence, guarantees the highest st<strong>and</strong>ards<br />

of resistance, is a noble alloy (ceramometal<br />

technique).<br />

The greatest limitation of this technique<br />

is the fact that the metal restoration has limited<br />

translucency, which means that esthetically<br />

it cannot compete <strong>with</strong> the st<strong>and</strong>ard<br />

that can be achieved when integral ceramics<br />

are used. Integral ceramics are indicated<br />

in cases where excellent esthetic results<br />

are required as these materials best imitate<br />

the color <strong>and</strong> luminosity of the natural tooth<br />

(Fig 3). One disadvantage however, is that<br />

these restorations have low mechanical resistance.<br />

Collarless ceramics supported by a<br />

metal core represent a solution that, in<br />

theory, combines the advantages of both<br />

techniques, eliminating the metal in the<br />

marginal portions so as to reduce the umbrella<br />

effect. 13 Today there is also a third option,<br />

which cuts a middle road <strong>and</strong> which<br />

is increasingly being used: zirconium.<br />

PATRONI<br />

Fig 2a <strong>and</strong> b Examples of zirconia copings <strong>with</strong> a well-represented margin to guarantee the mechanical<br />

strength.<br />

Fig 3 The best material for prosthetic reconstructions,<br />

in terms of esthetics, is the material able to mimic<br />

the translucency of natural teeth.<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010<br />

7

8<br />

CLINICAL APPLICATION<br />

a b<br />

Fig 4a Discolored natural tooth; the use of a high<br />

translucency crown would end in a unsatisfactory result.<br />

a b c<br />

a b<br />

Fig 6a <strong>and</strong> b A clinical case: the smile before <strong>and</strong> after treatment.<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010<br />

Fig 4b The ceramic crown supported by a zirconia<br />

core once cemented. The unfavorable tooth value is<br />

partially masked, increasing the core thickness. In spite<br />

of that, however, a discolored abutment appears<br />

through the marginal tissues anyway.<br />

Fig 5a to c Manufacturers<br />

advise a round<br />

shoulder or a chamfer<br />

preparation for a zirconia<br />

ceramic crown.

a b<br />

PATRONI<br />

Fig 7a <strong>and</strong> b The initial intraoral situation (a). Final result (b): the four incisors <strong>with</strong> zirconia crowns cemented.<br />

The m<strong>and</strong>ible was rehabilitated <strong>with</strong> an implant-supported fixed prosthesis.<br />

a b<br />

c d<br />

Fig 8a to d Maxillary anterior teeth before treatment (a). Four incisors prepared <strong>with</strong> a marginal chamfer (b).<br />

Four zirconia ceramic crowns on the master model (c). The end of treatment; the four upper incisors were reconstructed<br />

<strong>with</strong> zirconia ceramic crowns, the two cusps were restored by ceramic veneering (d).<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010<br />

9

10<br />

CLINICAL APPLICATION<br />

a b<br />

Fig 9a <strong>and</strong> b Some details of the crown margins <strong>and</strong> their tissue integration.<br />

a<br />

c<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010<br />

b<br />

Fig 10a to c In the case of a feather-<strong>edge</strong> preparation,<br />

it is necessary to finish <strong>with</strong> a metallic margin.<br />

When using a zirconia core, the margin should also be<br />

well represented, but the white color simplifies the esthetic<br />

result.

<strong>Zirconium</strong> has excellent mechanical <strong>and</strong><br />

esthetic characteristics. Mechanically, this<br />

is observed if the material is used in thickness<br />

of 0.5 mm or more. This thickness<br />

guarantees excellent mechanical resistance<br />

but partially diminishes the esthetic<br />

result. In some cases however, the thickness<br />

of the structure makes it possible to<br />

mask highly discolored prepared teeth, optimizing<br />

the esthetic results (Fig 4a <strong>and</strong> b).<br />

In order to obtain the very best esthetic<br />

results, it is necessary to use a thickness of<br />

0.3 mm, as this gives a high degree of luminosity<br />

<strong>and</strong> translucency. 14 It should be<br />

noted however, that these characteristics<br />

are inferior to those that can be obtained<br />

from integral ceramics (light transmission<br />

through 0.6 mm thick flat specimens of<br />

densely sintered alumina is 72% versus<br />

48% for densely sintered zirconia). 15<br />

For restorations <strong>with</strong> a zirconium oxide<br />

core, the producers recommend round<br />

shouldered or chamfered preparations as<br />

these are considered to be best for precision,<br />

resistance, <strong>and</strong> esthetic outcome<br />

(Figs 5 to 9).<br />

The presence of a margin means that<br />

excellent definition is required in the<br />

preparation phase <strong>and</strong> then adequate<br />

transferral of that information to the laboratory.<br />

These problems are easier to solve<br />

<strong>with</strong> a feather-<strong>edge</strong> preparation where the<br />

finishing line is no longer represented by<br />

a line but rather by an area (Table 5).<br />

The advantage of a butt preparation<br />

(shoulder or chamfer) is that it allows, from<br />

the margin, an adequate thickness of<br />

restoration materials (metal-opaque ceramics),<br />

reducing as much as possible<br />

the unsightliness of a metal border.<br />

However, it is necessary <strong>with</strong> a feather<strong>edge</strong><br />

preparation to have a well-represented<br />

<strong>and</strong> clinically evident metallic margin<br />

Table 5<br />

PATRONI<br />

(Fig 10). This may be considered an esthetic<br />

compromise <strong>and</strong> is usually indicated for<br />

complex perio-prosthetic rehabilitations.<br />

This limitation can be overcome by using<br />

a material such as zirconium, which makes<br />

it possible to create a white margin. While<br />

being clinically acceptable, this integrates<br />

well esthetically <strong>with</strong> the periodontal tissues<br />

<strong>with</strong>out needing to “invade” the dentogingival<br />

sulcus, which would complicate<br />

the prosthetic procedures <strong>and</strong> risk damage<br />

to the periodontal attachment.<br />

This led to the idea of combining zirconium<br />

oxide <strong>with</strong> the feather-<strong>edge</strong> preparation,<br />

a solution which, while not advised, is<br />

allowed by the producers on the condition<br />

that certain fundamental clinical <strong>and</strong> technical<br />

considerations are taken into account.<br />

Why feather-<strong>edge</strong><br />

marginal preparation?<br />

In the last 10 years, the prosthetic treatment<br />

plan has changed due to the introduction<br />

of implants. Indeed, it is because of implants<br />

that it is possible to treat individual<br />

or multiple edentulous areas (Fig 11), <strong>with</strong>out<br />

resorting to the preparation of healthy<br />

11<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010

12<br />

a<br />

CLINICAL APPLICATION<br />

c d<br />

Fig 11a to d In the last decade, the vast majority of clinicians prefer, in the case of partially edentulous areas<br />

between two healthy teeth, to place an implant instead of conventional prosthesis.<br />

teeth <strong>and</strong> sacrificing sound tissue to accommodate<br />

bridges. In the same way,<br />

many seriously compromised teeth, which<br />

until recently would have been treated in a<br />

prosthetic manner <strong>with</strong> complete crowns,<br />

can today be rehabilitated <strong>with</strong> indirect adhesive<br />

restorations.<br />

The indications for a fixed prosthesis<br />

have changed, <strong>and</strong> it is much less frequent<br />

that a healthy tooth is rehabilitated<br />

<strong>with</strong> a fixed prosthesis. It is even rarer that<br />

the clinician performs endodontic treatment<br />

for prosthetic reasons as vital teeth<br />

can be treated <strong>with</strong> restorative therapy.<br />

Therefore, prosthetic dentistry almost always<br />

follows the endodontic treatment<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010<br />

b<br />

needed to recover teeth which have been<br />

destroyed by decay.<br />

The carious lesion, moreover, does not<br />

only extend horizontally towards the pulp<br />

chamber but follows the line of the dental<br />

tubules <strong>and</strong> often extends apically <strong>and</strong> involves<br />

the periodontal attachment. For this<br />

reason, the majority of cases require a<br />

crown-lengthening procedure before the<br />

prosthetic phase in order to make the<br />

residual healthy tissue accessible <strong>and</strong> to<br />

re-establish a correct relationship <strong>with</strong><br />

these <strong>with</strong>out damaging the periodontal<br />

attachment (Figs 12 <strong>and</strong> 13).<br />

In the same surgical time, it is possible<br />

to carry out a feather-<strong>edge</strong> preparation of

a<br />

Fig 12a to c Surgical crown lengthening is frequently<br />

necessary to properly rehabilitate a seriously<br />

decayed tooth. During the surgery, the tooth is prepared<br />

up to the bony crest, <strong>and</strong> after suturing the temporary<br />

is relined. With a feather-<strong>edge</strong> preparation it is easy to<br />

obtain, 4 months after surgery, healthy tissues around<br />

the prepared tooth.<br />

a b<br />

PATRONI<br />

Fig 13 The tissues maturing around natural abutments 4 months after periodontal surgery (a). The teeth were<br />

prepared once the flap was raised <strong>and</strong> the final impression was obtained <strong>with</strong>out any further marginal preparation.<br />

The zirconia crowns once cemented (b).<br />

b<br />

c<br />

13<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010

14<br />

CLINICAL APPLICATION<br />

a b<br />

Fig 14a <strong>and</strong> b A clinical case: the initial smile (a) <strong>and</strong> the final smile (b).<br />

a b<br />

Fig 15a <strong>and</strong> b The tooth wear, the lost anterior occlusal relationships, <strong>and</strong> unpleasant esthetic (a). The final<br />

result (b).<br />

the abutments once the flap is raised 16-18<br />

while, at the same time, optimizing all<br />

other parameters that render the longterm<br />

results more predictable.<br />

These parameters involve:<br />

■ re-establishing biological dimensions<br />

■ lengthening short abutments<br />

■ recovering the ferrule effect<br />

■ correcting root proximities<br />

■ eliminating residual concavities following<br />

furcation barreling<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010<br />

■ bone surgery to eliminate the shallow<br />

infra-osseous pockets<br />

■ surgery to correct esthetic problems<br />

such as a gummy smile or to harmonize<br />

unsightly gingival trajectory arcs.<br />

The present approach involves, once the<br />

flap has been rised, a feather-<strong>edge</strong> preparation<br />

of the teeth as far as the osseous<br />

crest.

a b<br />

c d<br />

e f<br />

In order to be able to benefit from all of the<br />

advantages offered by a feather-<strong>edge</strong><br />

preparation, it is important to not modify<br />

this preparation once the surgical phase is<br />

over, unless to carry out small adjustments<br />

which do not involve the marginal area. Indeed,<br />

once the abutment is re-prepared in<br />

the impression stage, this may create a reference<br />

margin in the marginal finish area<br />

which is binding for the final restoration<br />

(Figs 14 to 20). When the tissues have ma-<br />

PATRONI<br />

Fig 16a to f Abutments immediately before surgery (a). Once the flap was raised during periodontal surgery,<br />

the teeth were prepared until the osseous crest (b). The flap sutured at the osseous crest (c). The abutments <strong>with</strong><br />

the first retraction cord inserted 10 months after surgery (d). The abutments <strong>with</strong> the second retraction cord inserted<br />

immediately before the final impression (e). The final cemented restorations (f).<br />

tured completely it will be possible to take<br />

a definitive impression <strong>and</strong> finalize the<br />

prosthetic restoration (Fig 21).<br />

There is a published technique which<br />

makes it possible to exploit the advantages<br />

of the feather-<strong>edge</strong> preparation carried<br />

out “blind,” that is, <strong>with</strong>out surgical access.<br />

19,20 Naturally, each preparation type<br />

has advantages <strong>and</strong> disadvantages. The<br />

choice of one rather than another is often<br />

guided by the different degrees of difficul-<br />

15<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010

16<br />

a<br />

CLINICAL APPLICATION<br />

Fig 17a to c The palatal view showing the healthy tissues around the crowns.<br />

Fig 18 The buccal emergence profile respecting the<br />

tissue health.<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010<br />

b c<br />

a<br />

b<br />

c<br />

Fig 19a to c Six months after the surgery, when<br />

teeth were prepared up to the osseous crest, the abutments<br />

were ready for the final prosthetic phase: occlusal<br />

(a) <strong>and</strong> buccal view (b). Cemented zirconium<br />

oxide prostheses (c).

a b<br />

c d<br />

e f<br />

g h<br />

Fig 20 The old restorations (a). The abutments once<br />

the previous prosthesis was removed (b). The periodontal<br />

intervention <strong>with</strong> the open flap abutment preparation<br />

(c). The final abutments 10 months after surgery (d). The<br />

red line on the master model represents where the technician<br />

placed the apical limit of the restoration after ditching;<br />

the black line represents the gingival level (e). The<br />

zirconia copings try-in (f). The tracing of the gingival scallop<br />

on the zirconia copings (g). Zirconia copings removed<br />

after try-in <strong>and</strong> tracing (the amount of the coping<br />

margin positioned into the sulcus is evident) (h). Oneyear<br />

follow-up, the good tissue integration is evident (i).<br />

i<br />

PATRONI<br />

17<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010

18<br />

CLINICAL APPLICATION<br />

a b<br />

Fig 21a <strong>and</strong> b The impression is easily obtained in<br />

cases of feather-<strong>edge</strong> preparation; the intra-crevicular<br />

part of the prepared tooth appears as a rising margin.<br />

ty <strong>and</strong> operative management. The feather-<strong>edge</strong><br />

preparation may be the solution<br />

for several clinical problems <strong>and</strong> simplifies<br />

the procedure beginning <strong>with</strong> the<br />

preparation itself <strong>and</strong> including the relining<br />

of the provisional, the final impression,<br />

<strong>and</strong> all further laboratory phases.<br />

Advantages of feather<strong>edge</strong><br />

marginal preparation<br />

■ Saves dental tissue: it is therefore indicated<br />

for teeth which have suffered serious<br />

periodontal damage as a consequence<br />

of periodontitis.<br />

■ Simplifies the final impression as there<br />

is no longer a finishing line but rather a<br />

finishing area.<br />

■ Relining the provisional is easier <strong>and</strong><br />

faster. Even in cases where the border of<br />

a temporary crown is slightly shortened,<br />

no marginal precision is lost as would<br />

happen in the case of a “short” provisional<br />

margin <strong>with</strong> a shoulder or chamfer<br />

preparation. In fact, the finishing tar-<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010<br />

get is represented by an area <strong>and</strong> not a<br />

line. However, the management of the<br />

esthetic zone is more delicate as a short<br />

margin would make it impossible to<br />

condition the gingival tissues <strong>and</strong> shape<br />

the prosthetic emergence profiles at an<br />

interproximal level.<br />

■ In cases of shoulder or chamfer preparations,<br />

the finish line is well defined <strong>and</strong><br />

is the line that the technician must refer<br />

to <strong>with</strong>out any doubt. The margin of the<br />

restoration must be unequivocally positioned<br />

at this level. On the other h<strong>and</strong>,<br />

<strong>with</strong> a feather-<strong>edge</strong> preparation, the<br />

prosthetic margin can be positioned at<br />

any level in an apico-coronal direction,<br />

as long as it respects the periodontal attachment.<br />

Once the structure has been<br />

realized, it could invade too deeply into<br />

the gingival sulcus. In this case, it can be<br />

shortened during the trial. In healthy<br />

conditions, the interproximal probing<br />

depth is approximately 3 mm <strong>and</strong> it is<br />

possible to receive a structure from the<br />

laboratory which finishes at this depth.<br />

From a clinical point of view, it is often<br />

unnecessary to position the prosthetic<br />

margin at this level interproximally, as in<br />

this zone there are no important esthetic<br />

requirements but only the need for tissue<br />

conditioning to recreate an adequate<br />

emergence profile. This profile is<br />

obtainable when the margin is positioned<br />

at 1 mm inside the sulcus. Therefore,<br />

any invasion by the restoration is<br />

unnecessary <strong>and</strong> could damage the<br />

periodontal attachment <strong>and</strong> make it difficult<br />

to remove any cement excess. Furthermore,<br />

adjusting the margin <strong>and</strong><br />

shortening it does not lead to any loss<br />

of precision nor will it compromise the<br />

esthetic result.

Disadvantages of the<br />

feather-<strong>edge</strong> marginal<br />

preparation<br />

The disadvantages of a feather-<strong>edge</strong><br />

preparation are emphasized in the case<br />

of a prosthetic rehabilitation using the<br />

ceramo-metal technique:<br />

■ The presence of a visible metal collar is<br />

necessary to guarantee precision <strong>and</strong><br />

resistance at the margin. This border,<br />

when not hidden in the gingival sulcus,<br />

is particularly unattractive <strong>and</strong> certainly<br />

unacceptable in the esthetic zone.<br />

■ If a metallic border is not properly<br />

formed there is a risk that a horizontal<br />

overhang will be created. 21<br />

This is potentially damaging for the periodontal<br />

tissues as it can retain bacteria<br />

<strong>and</strong> plaque. 22-25 The zirconia margin is<br />

m<strong>and</strong>atory in this area especially during<br />

cementing <strong>and</strong> while chewing; in fact, in<br />

these conditions there is a high concentration<br />

of stress on the margins which could<br />

cause ceramic chipping. 26,27<br />

In order to create enough space for the<br />

restoration material, there is risk of creating<br />

an over-tapered preparation. This does not<br />

guarantee a retentive <strong>and</strong> stable form for<br />

the restoration unless one resorts to additional<br />

retentions. 28<br />

All of the above is particularly disadvantageous<br />

in cases of:<br />

■ patients <strong>with</strong> a thin gingival biotype in<br />

whom the metal borders, even if intracrevicularly<br />

positioned, could show<br />

through the gingival margins, resulting<br />

in an esthetically unsatisfactory rehabilitation<br />

■ short abutments <strong>with</strong> a high risk of<br />

crown debonding. The vertical preparation<br />

is considered to be unsightly as the<br />

PATRONI<br />

elimination of less dental material gives<br />

the technician less space for ceramic<br />

stratification <strong>and</strong>, especially in the anterior<br />

teeth, in cases of even minimal gingival<br />

recession the metallic margin of<br />

the prosthesis is visible. With regard to<br />

precision, a vertical preparation (feather<br />

<strong>edge</strong> or bevel) may ensure a better seal<br />

than a horizontal one (shoulder or<br />

chamfer) before luting. In contrast, after<br />

the cementing it provides worse seating.<br />

This is due to the difficult defluxion of the<br />

cement at the prosthetic margin. 29,30 The<br />

final result therefore, in terms of precision,<br />

can be considered totally superimposable<br />

<strong>and</strong>, in any case, clinically acceptable<br />

for both types of preparation<br />

(vertical <strong>and</strong> horizontal). 29,31<br />

<strong>Zirconium</strong> oxide <strong>and</strong><br />

feather-<strong>edge</strong> preparation<br />

The marginal design recommended by<br />

the producers of zirconium oxide is a<br />

chamfer or round shouldered margin<br />

combined <strong>with</strong> a preparation that has a<br />

slightly increased taper compared to the<br />

conventional ones: 4 degrees per side<br />

compared to the vertical as opposed to 2<br />

to 3 degrees per side (Fig 22). 15,26,32 The authors'<br />

clinical experience suggests that zirconium<br />

oxide could also be used in vertical<br />

preparations, thereby combining a<br />

much simpler <strong>and</strong> much faster preparation<br />

<strong>with</strong> a material which is at least as mechanically<br />

resistant as gold, yet more esthetically<br />

pleasing.<br />

The design of the zirconium core must<br />

not differ from a core for a ceramo-metal<br />

restoration in the case of the feather-<strong>edge</strong><br />

preparation. The emergence profile must<br />

respect the periodontium <strong>and</strong> be easy to<br />

19<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010

20<br />

CLINICAL APPLICATION<br />

a b<br />

Fig 22a <strong>and</strong> b The ideal taper recommended in prosthetic dentistry is 2 degrees on each side (a). The recommended<br />

taper in the case of zirconia crowns is 4 degrees on each side (b).<br />

Fig 23 Chipping of the marginal crests: the two zirconia cores were designed in a st<strong>and</strong>ard way <strong>with</strong>out considering<br />

the necessity of ceramic support in relation to the occlusal contact points.<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010

a b<br />

c d<br />

clean, simulating the horizontal natural<br />

contour of the cementoenamel junction.<br />

It is possible to realize the <strong>edge</strong> of the<br />

restoration in zirconium <strong>with</strong> a form <strong>and</strong><br />

thickness similar to that of gold. The zirconium<br />

<strong>edge</strong> however, integrates better<br />

than a metal one. This is more noticeable<br />

in the molar region as it does not necessarily<br />

require intra-crevicular positioning<br />

to achieve satisfying esthetic results. 33 The<br />

zirconium oxide <strong>edge</strong> must be 0.5 to 0.7<br />

mm wide in order to guarantee resistance<br />

to chipping during insertion <strong>and</strong> luting<br />

phases.<br />

PATRONI<br />

Fig 24a to d False root realized, creating a forced pathway for the interproximal brush to clean the distal tooth<br />

surface.<br />

The main condition to be respected in order<br />

to minimize the chipping risk <strong>and</strong> obtain<br />

a successful long-term result, is that<br />

the ceramic has to be adequately supported<br />

by the underlying structure so that<br />

it will work during compression (Figs 23<br />

<strong>and</strong> 24). 34<br />

In extended structures, planning the<br />

connections is of the utmost importance<br />

<strong>and</strong> should be orientated appropriately: in<br />

the molar region the corono-apical sections<br />

should be most represented, while in<br />

the esthetic zone the vestibular-palatal<br />

thickness should be greater.<br />

21<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010

22<br />

a<br />

CLINICAL APPLICATION<br />

c d e<br />

f g<br />

Fig 25a to g A clinical case: frontal view of the abutments (a) <strong>and</strong> occlusal view (b). Details of healthy marginal<br />

tissues once the temporaries were removed: in the case of feather-<strong>edge</strong> preparation it is easier to guarantee<br />

the periodontal health around the prosthesis (c to e). Zirconia crowns on the master model (f). Frontal view<br />

of the final result (g).<br />

It is important to plan for a ceramic thickness<br />

that guarantees a good esthetic result<br />

<strong>with</strong>out the connections needing to be adjusted<br />

after the structure is finished, as any<br />

adjustments at that point cause the structure<br />

to be seriously weakened (Fig 25).<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010<br />

b<br />

Conclusions<br />

Although the combination of zirconium<br />

<strong>and</strong> feather-<strong>edge</strong> preparation requires further<br />

r<strong>and</strong>omized clinical studies in the<br />

medium <strong>and</strong> long term, it would seem to

offer an extremely interesting solution from<br />

a clinical point of view.<br />

Indeed, the zirconium confers to the<br />

restoration excellent esthetic <strong>and</strong> mechanical<br />

characteristics, as long as the plan<br />

allows for a rigorously personalized support<br />

structure for the overlaying ceramic.<br />

<strong>Feather</strong>-<strong>edge</strong> marginal preparation adapts<br />

well to the increasingly frequent requirement<br />

of pre-prosthetic periodontal surgical<br />

interventions. Moreover, the possibility of<br />

performing the final tooth preparation once<br />

the flap is raised reduces the number of interventions<br />

<strong>and</strong> the risk of invading the sulcus<br />

<strong>and</strong> damaging the supra-crestal fibers.<br />

This type of preparation, <strong>with</strong> its white<br />

zirconium borders, does not require that<br />

the margins be positioned deeply into the<br />

References<br />

1. Massironi D, Pascetta R, Ferraris<br />

F. Sistema <strong>CAD</strong>/<strong>CAM</strong><br />

Lava: l’importanza del fattore<br />

umano nella ricerca dell’ottimale<br />

precisione e adattamento<br />

marginale. Quintessenza Internazionale<br />

2004;2:39-50.<br />

2. Liu PR, Essig ME. Panorama of<br />

dental <strong>CAD</strong>/<strong>CAM</strong> restorative<br />

systems. Compend Contin<br />

Educ Dent<br />

2008;29:482,484,486-488.<br />

3. Beuer F, Schweiger J, Edelhoff<br />

D. Digital dentistry: an<br />

overview of recent developments<br />

for <strong>CAD</strong>/<strong>CAM</strong> generated<br />

restorations. Br Dent J<br />

2008;10;204:505-511.<br />

4. Vagkopoulou T, Koutayas SO,<br />

Koidis P, Strub JR. Zirconia in<br />

dentistry: Part 1. Discovering<br />

the nature of an upcoming<br />

bioceramic. Eur J Esthet Dent<br />

2009;4:130-151.<br />

5. Denry I, Kelly JR. State of the<br />

art of zirconia for dental applications.<br />

Dent Mater<br />

2008;24:299-307.<br />

6. Manicone PF, Rossi Iommetti<br />

P, Raffaelli L. An overview of<br />

zirconia ceramics: basic properties<br />

<strong>and</strong> clinical applications.<br />

J Dent 2007;35:819-826.<br />

7. Cehreli MC, Kökat AM, Akça K.<br />

<strong>CAD</strong>/<strong>CAM</strong> Zirconia vs. slipcast<br />

glass-infiltrated<br />

Alumina/Zirconia all-ceramic<br />

crowns: 2-year results of a r<strong>and</strong>omized<br />

controlled clinical<br />

trial. J Appl Oral Sci<br />

2009;17:49-55.<br />

8. Dion I, Rouais F, Baquey C,<br />

Lahaye M, Salmon R, Trut L et<br />

al. Physico-chemistry <strong>and</strong> cytotoxicity<br />

of ceramics: part I:<br />

characterization of ceramic<br />

powders. J Mater Sci Mater<br />

Med 1997;8:325-332.<br />

PATRONI<br />

sulcus, as the metal borders do not need<br />

to be hidden.<br />

It is therefore possible <strong>with</strong> this combination<br />

to reduce <strong>and</strong> simplify the clinical<br />

steps needed for the final prosthesis, while<br />

at the same time guaranteeing greater stability<br />

<strong>and</strong> health of the tissues over time.<br />

This is a simple <strong>and</strong> time saving technique<br />

that could be used on a daily basis<br />

by those clinicians striving to obtain an optimal<br />

clinical result.<br />

Acknowledgment<br />

The authors would like to thank Antonello Di Felice,<br />

CDT, Private practice, Rome, Italy for the great lab work<br />

for this study.<br />

9. Silva VV, Lameiras FS, Lobato<br />

ZI. Biological reactivity of zirconia-hydroxyapatite<br />

composites.<br />

J Biomed Mater Res<br />

2002;63:583-590.<br />

10. Covacci V, Bruzzese N, Maccauro<br />

G, Andreassi C, Ricci<br />

GA, Piconi C et al. In vitro evaluation<br />

of the mutagenic <strong>and</strong><br />

carcinogenic power of high<br />

purity zirconia ceramic. Biomaterials<br />

1999;20:371-376.<br />

11. Warashina H, Sakano S, Kitamura<br />

S, Yamauchi KI, Yamaguchi<br />

J, Ishiguro N,<br />

Hasegawa Y. Reaction to alumina,<br />

zirconia, titanium <strong>and</strong><br />

polyethylene particles implanted<br />

onto murine calvaria. Biomaterials<br />

2003;24:3655-3661.<br />

12. Miyazaki T, Hotta Y, Kunii J,<br />

Kuriyama S, Tamaki Y. A<br />

review of dental <strong>CAD</strong>/<strong>CAM</strong>:<br />

current status <strong>and</strong> future perspectives<br />

from 20 years of<br />

experience. Dent Mater J<br />

2009;28:44-56.<br />

23<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010

24<br />

CLINICAL APPLICATION<br />

13. Magne P, Magne M, Belser U.<br />

The esthetic width in fixed<br />

prosthodontics. J Prosthodont<br />

1999;8:106-118.<br />

14. Baldissara P, Llukacej A,<br />

Val<strong>and</strong>ro LF, Bottino MA, Scotti<br />

R. Traslucency of ZrO 2 copings<br />

for all-ceramic FPDs.<br />

Academy of Dental Materials,<br />

23-25 Oct 2006, Sao Paulo,<br />

Brazil.<br />

15. Sadan A, Blatz M, Lang B.<br />

Clinical consideration for<br />

densely sintered alumina <strong>and</strong><br />

zirconia restoration. Int J Periodontics<br />

Restorative Dent<br />

2005;25:213-219.<br />

16. Carnevale G, Freni Sterrantino<br />

S, Di Febo G. Soft <strong>and</strong> hard<br />

tissue wound healing following<br />

tooth preparation to the alveolar<br />

crest. Int J Periodontics<br />

Restorative Dent 1983;3:36-53.<br />

17. Carnevale G, Di Febo G, Biscaro<br />

L, Freni Sterrantino SF,<br />

Fuzzi M. An in vivo study of<br />

teeth reprepared during periodontal<br />

surgery. Int J Periodontics<br />

Restorative Dent<br />

1990;10:40-55.<br />

18. Carnevale G, Di Febo G, Fuzzi<br />

M. A retrospective analysis of<br />

the perio-prosthetic aspect of<br />

teeth reprepared during periodontal<br />

surgery. J Clin Periodontol<br />

1990;17:313-316.<br />

19. Loi I, Scutella‘ F, Galli F. Tecnica<br />

di preparazione orientata<br />

biologicamente (B.O.P.T) un<br />

nuovo approccio nella<br />

preparazione protesica in<br />

odontostomatologia. Quintessenza<br />

Internazionale<br />

2008;24:69-74.<br />

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY<br />

VOLUME 5 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2010<br />

20. Loi I, Scutella‘ F, Galli F, Di<br />

Felice A. Il contorno coronale<br />

protesico con la tecnica di<br />

preparazione B.O.P.T. (Biologically<br />

Oriented Preparation Tecnique):<br />

Considerazioni tecniche.<br />

Quintessenza<br />

Internazionale 2009;25:19-30.<br />

21. Martignoni M, Schonenberger<br />

A. Precision fixed prosthodontics:<br />

clinical <strong>and</strong> laboratory<br />

aspects. Chicago: Quintessence,<br />

1990:52-57.<br />

22.Orkin DA, Reddy J, Bradshaw<br />

D. The relationship of the position<br />

of crown margins to gingival<br />

health. J Prosthet Dent<br />

1987;57:421-424<br />

23.Flores-de-Jacoby L, Zafiropoulos<br />

GG, Ciancio S. The effect<br />

of crown margin location on<br />

plaque <strong>and</strong> periodontal health.<br />

Int J Periodontics Restorative<br />

Dent 1989;9:197-205.<br />

24. Valderhaug J, Birkel<strong>and</strong> JM.<br />

Periodontal conditions in<br />

patients 5 years following<br />

insertion of fixed prostheses.<br />

Pocket depth <strong>and</strong> loss of<br />

attachment. J Oral Rehabil<br />

1976;3:237-243.<br />

25.Valderhaug J, Birkel<strong>and</strong> JM.<br />

Periodontal conditions <strong>and</strong><br />

carious lesions following the<br />

insertion of fixed protheses. A<br />

10-year follow-up study. Int<br />

Dent J 1981;30:296.<br />

26.Hoard RJ, Caputo AA, Contino<br />

RM, Koenig ME. Intracoronal<br />

pressure during crown cementation.<br />

J Prosthet Dent<br />

1978;40:520-525.<br />

27. Wilson PR, Goodkind RJ,<br />

Delong R, Sakaguchi R. Deformation<br />

of crowns during<br />

cementation. J Prosthet Dent<br />

1990;4:601-609.<br />

28.Schillingburg HT, Hobo S,<br />

Whitsett LD, Jacobi R, Brackett<br />

SE. Fundamentals of fixed<br />

prosthodontics, ed 3. Chicago:<br />

Quintessence Publishing,<br />

1997:119-169.<br />

29. Hunter AJ, Hunter AR. Gingival<br />

margins for crowns: A review<br />

<strong>and</strong> discussion. Part 2: Discrepancies<br />

<strong>and</strong> configurations.<br />

J Prosthet Dent 1990;64:<br />

636-642.<br />

30. Gavelis JR, Morency JD, Riley<br />

ED, Sozio RB. The effect of<br />

various finish line preparations<br />

on the marginal seal <strong>and</strong><br />

occlusal seat of full crown<br />

preparations. J Prosthet Dent<br />

1981;45:138-145.<br />

31 Fradeani M, Barducci G.<br />

Esthetic Rehabilitation in Fixed<br />

Prosthodontics, Volume 2—<br />

Prosthetic Treatment: A Systematic<br />

Approach to Esthetic,<br />

Biologic, <strong>and</strong> Functional Integration.<br />

London: Quintessence<br />

Publishing, 2008:330-351.<br />

32.El Ebrashi MK, Craig RG, Peyton<br />

FA. Experimental stress<br />

analysis of dental restorations.<br />

Part III. The concept of the<br />

geometry of proximal margins.<br />

J Prosthet Dent 1969;22:333.<br />

33.Scotti R, Kantorski KZ, Monaco<br />

C, Val<strong>and</strong>ro LF, Ciocca L, Bottino<br />

MA. SEM evaluation of in<br />

situ early bacterial colonization<br />

on a Y-TZP ceramic: a pilot<br />

study. Int J Prosthodont<br />

2007;20:419-422.<br />

34.Sailer I, Gauckler LJ, Hammerle<br />

CHF. Five-year clinical<br />

results of zirconia frameworks<br />

for posterior fixed partial dentures.<br />

Int J Prosthodont<br />

2007;20:383-388.