- Page 2:

This page intentionally left blank

- Page 8:

COLLOQUIAL AND LITERARY LATIN edite

- Page 12:

In honour of J. N. Adams

- Page 18:

viii Contents 9 The fragments of Ca

- Page 22:

Contributors professor brigitte l.

- Page 26:

Acknowledgements Thanks are due abo

- Page 30:

xiv Foreword the University Medal f

- Page 34:

xvi Foreword and authors are concer

- Page 38:

xviii Foreword that he has studied

- Page 44:

chapter 1 Introduction Eleanor Dick

- Page 48:

Introduction 5 lacks a colloquial r

- Page 52:

chapter 2 Colloquial language in li

- Page 56:

Colloquial language in linguistic s

- Page 60:

Colloquial language in linguistic s

- Page 64:

Roman authors on colloquial languag

- Page 68:

Roman authors on colloquial languag

- Page 72:

Roman authors on colloquial languag

- Page 76:

Roman authors on colloquial languag

- Page 80:

Roman authors on colloquial languag

- Page 84:

Roman authors on colloquial languag

- Page 88:

Roman authors on colloquial languag

- Page 92:

Roman authors on colloquial languag

- Page 96:

Roman authors on colloquial languag

- Page 100:

Roman authors on colloquial languag

- Page 104:

Roman authors on colloquial languag

- Page 108:

Roman authors on colloquial languag

- Page 112:

Roman authors on colloquial languag

- Page 116:

Roman authors on colloquial languag

- Page 120:

Roman authors on colloquial languag

- Page 124:

Colloquial language in literary stu

- Page 128:

Colloquial language in literary stu

- Page 132:

Colloquial language in literary stu

- Page 136:

Colloquial language in literary stu

- Page 140:

Colloquial language in literary stu

- Page 144:

Colloquial language in literary stu

- Page 148:

Colloquial language in literary stu

- Page 152:

Colloquial language in literary stu

- Page 156:

Colloquial language in literary stu

- Page 160:

Colloquial language in literary stu

- Page 164:

Colloquial language in literary stu

- Page 168:

chapter 5 Preliminary conclusions E

- Page 172:

Preliminary conclusions 67 adhere t

- Page 176:

part ii Early Latin

- Page 182:

72 wolfgang david cirilo de melo Th

- Page 186:

74 wolfgang david cirilo de melo Th

- Page 190:

76 wolfgang david cirilo de melo Th

- Page 194:

78 wolfgang david cirilo de melo en

- Page 198:

80 wolfgang david cirilo de melo hy

- Page 202:

82 wolfgang david cirilo de melo He

- Page 206:

84 wolfgang david cirilo de melo Ex

- Page 210:

86 wolfgang david cirilo de melo Pl

- Page 214:

88 wolfgang david cirilo de melo Wh

- Page 218:

90 wolfgang david cirilo de melo su

- Page 222:

92 wolfgang david cirilo de melo In

- Page 226:

94 wolfgang david cirilo de melo sh

- Page 230:

96 wolfgang david cirilo de melo bu

- Page 234:

98 wolfgang david cirilo de melo It

- Page 238:

chapter 7 Greeting and farewell exp

- Page 242:

102 paolo poccetti (7) eugae, Demip

- Page 246:

104 paolo poccetti are more common

- Page 250:

106 paolo poccetti information abou

- Page 254:

108 paolo poccetti meaning but need

- Page 258:

110 paolo poccetti these expression

- Page 262:

112 paolo poccetti In Plautus’ di

- Page 266:

114 paolo poccetti (42) Tullius Ter

- Page 270:

116 paolo poccetti a grammaticalisa

- Page 274:

118 paolo poccetti (57) . -. . .

- Page 278:

120 paolo poccetti (64) mi homo et

- Page 282:

122 paolo poccetti This utterance i

- Page 286:

124 paolo poccetti This et tu greet

- Page 290:

126 paolo poccetti the vale that fo

- Page 294:

128 hilla halla-aho and peter krusc

- Page 298:

130 hilla halla-aho and peter krusc

- Page 302:

132 hilla halla-aho and peter krusc

- Page 306:

134 hilla halla-aho and peter krusc

- Page 310:

136 hilla halla-aho and peter krusc

- Page 314:

138 hilla halla-aho and peter krusc

- Page 318:

140 hilla halla-aho and peter krusc

- Page 322:

142 hilla halla-aho and peter krusc

- Page 326:

144 hilla halla-aho and peter krusc

- Page 330:

146 hilla halla-aho and peter krusc

- Page 334:

148 hilla halla-aho and peter krusc

- Page 338:

150 hilla halla-aho and peter krusc

- Page 342:

152 hilla halla-aho and peter krusc

- Page 346:

chapter 9 The fragments of Cato’s

- Page 350:

156 john briscoe of colloquial orig

- Page 354:

158 john briscoe be that Cato himse

- Page 358:

160 john briscoe is common in old L

- Page 364:

chapter 10 Hyperbaton and register

- Page 368:

Hyperbaton and register in Cicero 1

- Page 372:

Hyperbaton and register in Cicero 1

- Page 376:

Hyperbaton and register in Cicero 1

- Page 380:

Hyperbaton and register in Cicero 1

- Page 384:

Hyperbaton and register in Cicero 1

- Page 388:

Hyperbaton and register in Cicero 1

- Page 392:

Hyperbaton and register in Cicero 1

- Page 396:

Hyperbaton and register in Cicero 1

- Page 400:

Hyperbaton and register in Cicero 1

- Page 404:

Hyperbaton and register in Cicero 1

- Page 408:

Hyperbaton and register in Cicero 1

- Page 412:

Notes on the language of Marcus Cae

- Page 416:

Notes on the language of Marcus Cae

- Page 420:

Notes on the language of Marcus Cae

- Page 424:

Notes on the language of Marcus Cae

- Page 428:

Notes on the language of Marcus Cae

- Page 432:

26-30 31-60 21-25 Notes on the lang

- Page 436:

Notes on the language of Marcus Cae

- Page 440:

Notes on the language of Marcus Cae

- Page 444:

chapter 12 Syntactic colloquialism

- Page 448:

Syntactic colloquialism in Lucretiu

- Page 452:

Syntactic colloquialism in Lucretiu

- Page 456:

Syntactic colloquialism in Lucretiu

- Page 460:

Syntactic colloquialism in Lucretiu

- Page 464:

Syntactic colloquialism in Lucretiu

- Page 468:

Syntactic colloquialism in Lucretiu

- Page 472:

Syntactic colloquialism in Lucretiu

- Page 476:

Syntactic colloquialism in Lucretiu

- Page 480:

Syntactic colloquialism in Lucretiu

- Page 484:

Syntactic colloquialism in Lucretiu

- Page 488:

Syntactic colloquialism in Lucretiu

- Page 492:

Syntactic colloquialism in Lucretiu

- Page 496:

chapter 13 Campaigning for utilitas

- Page 500:

Style, grammar and philosophy in C.

- Page 504:

Style, grammar and philosophy in C.

- Page 508:

Style, grammar and philosophy in C.

- Page 512:

Style, grammar and philosophy in C.

- Page 516:

Style, grammar and philosophy in C.

- Page 520:

Style, grammar and philosophy in C.

- Page 524:

chapter 14 The style of the Bellum

- Page 528:

The style of the Bellum Hispaniense

- Page 532:

The style of the Bellum Hispaniense

- Page 536:

The style of the Bellum Hispaniense

- Page 540:

The style of the Bellum Hispaniense

- Page 544:

The style of the Bellum Hispaniense

- Page 548:

chapter 15 Grist to the mill: the l

- Page 552:

The quotidian in Horace, Satire 1.5

- Page 556:

The quotidian in Horace, Satire 1.5

- Page 560:

The quotidian in Horace, Satire 1.5

- Page 564:

The quotidian in Horace, Satire 1.5

- Page 568:

The quotidian in Horace, Satire 1.5

- Page 572:

Divine discourse in Virgil’s Aene

- Page 576: Divine discourse in Virgil’s Aene

- Page 580: Divine discourse in Virgil’s Aene

- Page 584: Divine discourse in Virgil’s Aene

- Page 588: Divine discourse in Virgil’s Aene

- Page 592: Divine discourse in Virgil’s Aene

- Page 596: part iv Early Principate

- Page 602: 282 martti leiwo lower-class dialog

- Page 606: 284 martti leiwo characterise him a

- Page 610: 286 martti leiwo that for Petronius

- Page 614: 288 martti leiwo for even the suppo

- Page 618: 290 martti leiwo creates a continuu

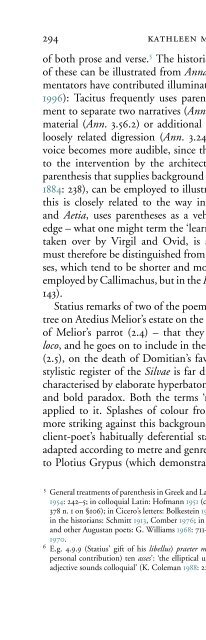

- Page 622: chapter 18 Parenthetical remarks in

- Page 628: Parenthetical remarks in the Silvae

- Page 632: Parenthetical remarks in the Silvae

- Page 636: Parenthetical remarks in the Silvae

- Page 640: Parenthetical remarks in the Silvae

- Page 644: Parenthetical remarks in the Silvae

- Page 648: Parenthetical remarks in the Silvae

- Page 652: Parenthetical remarks in the Silvae

- Page 656: Parenthetical remarks in the Silvae

- Page 660: Parenthetical remarks in the Silvae

- Page 664: Parenthetical remarks in the Silvae

- Page 668: Parenthetical remarks in the Silvae

- Page 672: 1.5 Balneum Claudii Etrusci: 61-2 1

- Page 676:

Colloquial Latin in Martial’s epi

- Page 680:

Colloquial Latin in Martial’s epi

- Page 684:

Colloquial Latin in Martial’s epi

- Page 688:

Colloquial Latin in Martial’s epi

- Page 692:

Colloquial Latin in Martial’s epi

- Page 696:

Colloquial Latin in Martial’s epi

- Page 700:

chapter 20 Current and ancient coll

- Page 704:

Current and ancient colloquial in G

- Page 708:

Current and ancient colloquial in G

- Page 712:

Current and ancient colloquial in G

- Page 716:

chapter 21 Forerunners of Romance -

- Page 720:

Forerunners of Romance -mente adver

- Page 724:

Forerunners of Romance -mente adver

- Page 728:

Forerunners of Romance -mente adver

- Page 732:

Forerunners of Romance -mente adver

- Page 736:

Forerunners of Romance -mente adver

- Page 740:

Forerunners of Romance -mente adver

- Page 744:

Forerunners of Romance -mente adver

- Page 752:

chapter 22 Late sparsa collegimus:

- Page 756:

The sources and language of Jordane

- Page 760:

The sources and language of Jordane

- Page 764:

The sources and language of Jordane

- Page 768:

The sources and language of Jordane

- Page 772:

The sources and language of Jordane

- Page 776:

The sources and language of Jordane

- Page 780:

The sources and language of Jordane

- Page 784:

The sources and language of Jordane

- Page 788:

The sources and language of Jordane

- Page 792:

The tale of Frodebert’s tail 377

- Page 796:

The tale of Frodebert’s tail 379

- Page 800:

The tale of Frodebert’s tail 381

- Page 804:

The tale of Frodebert’s tail 383

- Page 808:

The tale of Frodebert’s tail 385

- Page 812:

The tale of Frodebert’s tail 387

- Page 816:

The tale of Frodebert’s tail 389

- Page 820:

The tale of Frodebert’s tail 391

- Page 824:

The tale of Frodebert’s tail 393

- Page 828:

The tale of Frodebert’s tail 395

- Page 832:

The tale of Frodebert’s tail 397

- Page 836:

The tale of Frodebert’s tail 399

- Page 840:

The tale of Frodebert’s tail 401

- Page 844:

The tale of Frodebert’s tail 403

- Page 848:

The tale of Frodebert’s tail 405

- Page 852:

Latin colloquies 407 fetch his clot

- Page 856:

Latin colloquies 409 composed in La

- Page 860:

Latin colloquies 411 gloss, leaving

- Page 864:

Latin colloquies 413 and u in texts

- Page 868:

Latin colloquies 415 (E. Löfstedt

- Page 872:

Latin colloquies 417 Similarly, in

- Page 876:

chapter 25 Conversations in Bede’

- Page 880:

Conversations in Bede’s Historia

- Page 884:

Conversations in Bede’s Historia

- Page 888:

Conversations in Bede’s Historia

- Page 892:

Conversations in Bede’s Historia

- Page 896:

Conversations in Bede’s Historia

- Page 900:

Abbreviations abbreviations of anci

- Page 904:

Abbreviations 433 Orat. Orator Phil

- Page 908:

Abbreviations 435 Jord. Jordanes Go

- Page 912:

Abbreviations 437 Quint. M. Fabius

- Page 916:

Abbreviations 439 A. Riese, Antholo

- Page 920:

References Abbot, F. F. 1907. ‘Th

- Page 924:

References 443 (edd.), Latin et lan

- Page 928:

References 445 Bettini, M. 1982.

- Page 932:

References 447 Calboli Montefusco,

- Page 936:

References 449 Cordier, A. 1939. É

- Page 940:

References 451 Fantham, E. 1972. Co

- Page 944:

References 453 Goodyear, F. R. D. 1

- Page 948:

References 455 Herren, M. W. 1995.

- Page 952:

References 457 1927a. C. Iuli Caesa

- Page 956:

References 459 Leumann, M. 1947.

- Page 960:

References 461 (ed.) 1923. Incerti

- Page 964:

References 463 Norden, E. 1899. Die

- Page 968:

References 465 1993a. ‘Aspetti e

- Page 972:

References 467 Sato, S. 1990. ‘Ch

- Page 976:

References 469 1945. ‘Colloquial

- Page 980:

References 471 Weissenborn, W. and

- Page 984:

Ablabius 360 ablative absolute 189

- Page 988:

e for i 360, 413 elegy 215 élite s

- Page 992:

Neoteric poetry 63 n. 60 Nepos 245,

- Page 996:

spelling xvii, 20 n. 15, 54, 232 wi

- Page 1000:

(a) Latin words and expressions ab

- Page 1004:

et tu 123-4 etenim 220-1, 364-5 eti

- Page 1008:

opino(r) 17 with n. 10, 146, 224, 3

- Page 1012:

tra(ns)vorsus 158-9, 253 n. 94; de

- Page 1016:

Accius 2 Ribbeck: 141 3: 140 123: 1

- Page 1020:

4.1: 244, 248 n. 36, 250 n. 58 4.2:

- Page 1024:

7.48.1: 251 n. 69 7.77.14: 247 n. 3

- Page 1028:

Fat. 24: 38 38: 44 n. 5 Fin. 1.5: 1

- Page 1032:

5.10: 413, 417 n. 24 5.14-15: 416 5

- Page 1036:

Furius Bibaculus fr. 15 Courtney: 2

- Page 1040:

2.1.32: 44 n. 5 2.1.46: 263 2.2.10:

- Page 1044:

1069: 57 n. 39 1130: 20 1249: 43 n.

- Page 1048:

5.78.22: 323 5.82.3: 322 5.83.2: 32

- Page 1052:

41.12: 282 42.1-7: 282 42.4: 49 43.

- Page 1056:

533: 332 n. 6 579: 94 593: 213 602:

- Page 1060:

4.43: 26 4.44: 163, 174, 177 4.45:

- Page 1064:

4.4.57: 317 4.4.58-60: 317 4.5: 315

- Page 1068:

4.117-19: 272 4.271: 276 5.311: 248