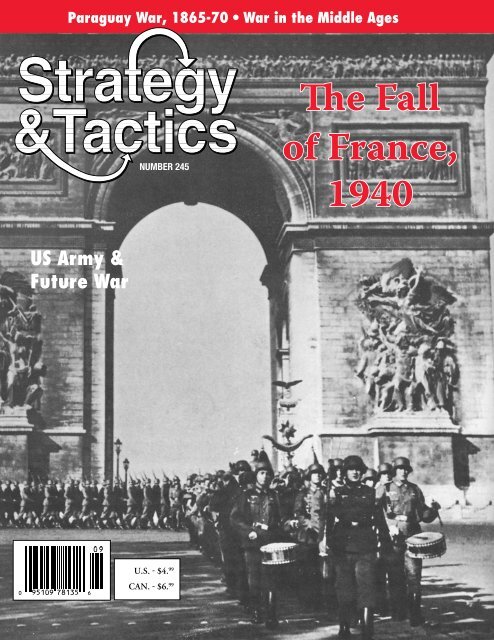

The Fall of France, 1940 - Strategy & Tactics Press

The Fall of France, 1940 - Strategy & Tactics Press The Fall of France, 1940 - Strategy & Tactics Press

Paraguay War, 1865-70 • War in the Middle Ages US Army & Future War Number 245 U.S. - $4. 99 CAN. - $6. 99 The Fall of France, 1940 strategy & tactics 1

- Page 2 and 3: Decision Games… Games publisher o

- Page 4 and 5: editor-in-Chief: Joseph miranda Fyi

- Page 6 and 7: 6 #245 The Guerra Grande: The War o

- Page 8 and 9: 8 #245 Geography of the Paraguayan

- Page 10 and 11: 10 #245 By early autumn 1866 (remem

- Page 12 and 13: 12 #245 Military Commanders of the

- Page 14 and 15: 14 #245 the capital. In March, a Pa

- Page 16 and 17: The Battle of Curupaity, 22 Septemb

- Page 18 and 19: 18 #245 THE COST Losses: Allies: So

- Page 20 and 21: 20 #245

- Page 22 and 23: 22 #245 Crossroads of a campaign: G

- Page 24 and 25: 24 #245 France 1940: the Campaign B

- Page 26 and 27: 26 #245 Beachhead in reverse: Allie

- Page 28 and 29: French Light Mechanized Division 28

- Page 30 and 31: 30 #245 name address Bibliography B

- Page 32 and 33: 32 #245 “US-Japan cooperation wil

- Page 34 and 35: 34 #245 For Your information launch

- Page 36 and 37: the Long tradition: 36 #245 50 issu

- Page 38 and 39: 38 #245 The Art of War in the Middl

- Page 40 and 41: 40 #245 mates of Roman strength ran

- Page 42 and 43: 42 #245 Only forces of comparable m

- Page 44 and 45: Clash of arms: medieval soldiery en

- Page 46 and 47: 46 #245 100 Years of War Once again

- Page 48 and 49: 48 #245 Instrument of war: an early

- Page 50 and 51: 50 #245 TACTICAL FILE: Gonzalvo de

Paraguay War, 1865-70 • War in the Middle Ages<br />

US Army &<br />

Future War<br />

Number 245<br />

U.S. - $4. 99<br />

CAN. - $6. 99<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Fall</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>France</strong>,<br />

<strong>1940</strong><br />

strategy & tactics 1

Decision Games… Games<br />

publisher <strong>of</strong> military history magazines & games<br />

Nine Navies War<br />

Nine Navies War begins at the start <strong>of</strong> 1915, after a victorious Germany has<br />

overrun <strong>France</strong> the year before. (Perhaps the BEF didn’t land on time or at all,<br />

or they got bottled up in Mons, or the Germans kept to their full-blown, keep<br />

the right super-strong and pull back on the left Schlieffen Plan scheme, thereby<br />

bagging two French armies in the Rhineland, etc.) Italy, seeing the German victory<br />

train leaving the station, joins the Central Powers, as do Spain and Greece. All <strong>of</strong><br />

which makes for a dreadnought showdown in the Mediterranean, Atlantic Ocean<br />

and North Seas, as the avidly Mahanist Kaiser Wilhelm seeks to finally defeat the<br />

Royal Navy and thus make Germany into a true global power.<br />

It will be the battleships <strong>of</strong> Britain, Russia and ‘Free <strong>France</strong>’ versus those <strong>of</strong><br />

Germany, Italy, Turkey, Austria-Hungary and the captured portion <strong>of</strong> the divided<br />

French fleet. (Each French ship is rolled for at the start <strong>of</strong> every game. Each can<br />

be scuttled, go over to the British, or be captured by the Germans.) <strong>The</strong>re will<br />

also be the possibility <strong>of</strong> later US entry when/if the Japanese switch sides in the<br />

Pacific and launch a dastardly surprise attack that finally draws in the Yanks.<br />

Victory is determined on victory points awarded for controlling the various sea<br />

zones around Europe. <strong>The</strong> geography thereby creates a kind <strong>of</strong> “two front war,”<br />

one in the Mediterranean and one in the Atlantic. <strong>The</strong> Central Powers player is<br />

also able to win a “sudden death” victory by controlling the waters immediately<br />

surrounding the British Isles for one full year (three turns). If he does so, the<br />

British have just been starved into submission.<br />

All the battleships and battle cruisers afloat during that era, along with three<br />

late-game British aircraft carriers, are represented in the various nations’ orders<br />

<strong>of</strong> battle, as well as ships that were scheduled to be completed during 1919 if the<br />

war had gone on that long.<br />

Random events account for the larger developments taking place in the ground<br />

war still going on in Russia, the Middle East and colonial Africa, as well as<br />

accounting for capital ship losses due to mines, unexplained internal explosions,<br />

as well as submarine, coastal artillery and land based aircraft attack.<br />

A top <strong>of</strong> the line German battleship like the Baden has factors (attack-defensemaximum<br />

speed) <strong>of</strong> 6-8-5, while the British battle cruiser Tiger is a 4-4-7. Topdown,<br />

full-color, historic ship icons identify every ship.<br />

<strong>The</strong> game uses a derivation <strong>of</strong> the classic Avalon Hill War at Sea. 9NW is<br />

simple two-player game with a short three-turn “1915” scenario, which can easily<br />

be finished in one sitting, as well as a 12-turn “campaign game” that will require<br />

about eight hours to play.<br />

Contents: 1 22x34" map, 492 die-cut counters, rules book. $50. 00<br />

2 #245<br />

3<br />

Barham<br />

6-7-6<br />

Br<br />

10<br />

Borodino<br />

6-5-7<br />

RN<br />

Fried.<br />

der Grosse<br />

4-8-5<br />

Ge<br />

10 * 10 *<br />

C. Colombo<br />

6-7-5<br />

It<br />

3-3-4<br />

SP<br />

2-2-3<br />

GK<br />

Indiana<br />

7-9-5<br />

US<br />

Tegetth<strong>of</strong><br />

5-5-4<br />

AH<br />

Jean Bart<br />

5-5-5<br />

FG<br />

QTY Title Price Total<br />

Nine Navies War $50<br />

Land Without End $50<br />

Luftwaffe $50<br />

Storm <strong>of</strong> Steel (pg 60) $140<br />

Shipping ChargeS<br />

1st unit Adt’l units Type <strong>of</strong> Service<br />

$8 $2 UPS Ground/USPS Priority Mail<br />

17 2 Canada<br />

21 4 Europe, South America<br />

22 5 Asia, Australia<br />

10 *<br />

Sachsen<br />

6-8-5<br />

Ge<br />

12<br />

CV Vindictive<br />

1-0-1-8<br />

Br<br />

4-5-6<br />

Tu

Land Without<br />

End<br />

Land Without End: <strong>The</strong><br />

Barbarossa Campaign, 1941 is a two-player, low-to-intermediate<br />

complexity, strategic-level simulation <strong>of</strong> the German attempt to conquer<br />

the Soviet Union in 1941. <strong>The</strong> German player is on the <strong>of</strong>fensive,<br />

attempting to win the game by rapidly seizing key cities. <strong>The</strong><br />

Soviet player is primarily on the defensive, but the situation also<br />

requires he prosecute counterattacks throughout much <strong>of</strong> the game.<br />

Game play encompasses the period that began with the Germans<br />

launching their attack on 22 June 1941, and ends on 7 December<br />

<strong>of</strong> the same year. By that time it had become clear the invaders had<br />

shot their bolt without achieving their objectives. <strong>The</strong> game may end<br />

sooner than the historic termination time if the German player is able<br />

to advance so quickly he causes the overall political, socio-economic<br />

and military collapse <strong>of</strong> the Soviet Union.<br />

Each hexagon on the map represents approximately 20 miles (32<br />

km) from side to opposite side. <strong>The</strong> units <strong>of</strong> maneuver for both sides<br />

are primarily divisions, along with Axis-satellite and Soviet corps (and<br />

one army) <strong>of</strong> various types. <strong>The</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> the general air superiority<br />

enjoyed by the Germans throughout the campaign are built into the<br />

movement and combat rules. Each game turn represents one week.<br />

Players familiar with other strategic-level east front designs will<br />

note the unique aspects <strong>of</strong> LWE lie in its rules governing the treatment<br />

<strong>of</strong> supply, the capture <strong>of</strong> Moscow, and the Stalin line.<br />

Contents: 1 22x34" map, 700 die-cut counters, rules book. $50. 00<br />

2 X X X<br />

*<br />

6-6<br />

X X X<br />

5-8<br />

2 XXXX<br />

6-<br />

X X<br />

X X<br />

CSIR<br />

HF<br />

T<br />

5-10<br />

ICA<br />

3<br />

6-10<br />

VIII<br />

Luftwaffe<br />

Luftwaffe is an update <strong>of</strong> the classic Avalon Hill game covering the US<br />

strategic bombing campaign over Europe in World War II. As US commander,<br />

your mission is to eliminate German industrial complexes. You<br />

select the targets, direct the bombers, and plan a strategy intended to defeat<br />

the Luftwaffe. As the German commander, the entire arsenal <strong>of</strong> Nazi aircraft<br />

is at your disposal. Turns represent three months each, with German reinforcements<br />

keyed to that player’s production choices. Units are wings and<br />

squadrons, and they’re rated by type, sub-type, firepower, maneuverability<br />

and endurance. <strong>The</strong>re are rules for radar, electronic warfare, variable production<br />

strategies, aces, target complexes, critical industries and diversion<br />

<strong>of</strong> forces to support the ground war. <strong>The</strong> orders <strong>of</strong> battle are much the same<br />

as in the original game, though the German player now has to plan ahead if<br />

he wants to get jets.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are also other new targets on the map, such as the German electric<br />

power grid. In the original game the US player had to bomb all the targets<br />

on the map to win. Given the way the victory point system now works, the<br />

Americans need bomb about four out <strong>of</strong> the five major target systems to<br />

win, thereby duplicating the historic result.<br />

Contents: 1 22x34" map, 280 die-cut counters, rules and PACs. $50. 00<br />

name<br />

addreSS<br />

CiTy, STaTe Zip<br />

phone email<br />

ViSa/mC (only)#<br />

expiraTion daTe<br />

SignaTure<br />

Now Available<br />

strategy & tactics 3

editor-in-Chief: Joseph miranda<br />

Fyi editor: Ty Bomba<br />

design • graphics • Layout: Callie Cummins<br />

Copy Editors: Ty Bomba, Lewis Goldberg, Paul<br />

Koenig and dav Vandenbroucke.<br />

map graphics: meridian mapping<br />

Publisher: Christopher Cummins<br />

Advertising: Rates and specifications available<br />

on request. Write P.O. Box 21598, Bakersfield CA<br />

93390.<br />

SUBSCRIPTION RATES are: Six issues per year—<br />

the United States is $109.97. Non-U.S. addresses<br />

are shipped via Airmail: Canada add $20 per year.<br />

Overseas add $26 per year. International rates are<br />

subject to change as postal rates change.<br />

Six issues per year-Newsstand (magazine only)the<br />

United States is $19.97/1 year. Non-U.S. addresses<br />

are shipped via Airmail: Canada add $10<br />

per year. Overseas add $13 per year.<br />

All payments must be in U.S. funds drawn on a<br />

U.S. bank and made payable to <strong>Strategy</strong> & <strong>Tactics</strong><br />

(Please no Canadian checks). Checks and money<br />

orders or VISA/MasterCard accepted (with a<br />

minimum charge <strong>of</strong> $40). All orders should be sent<br />

to Decision Games, P.O. Box 21598, Bakersfield<br />

CA 93390 or call 661/587-9633 (best hours to<br />

call are 9am-12pm PDT, M-F) or use our 24-hour<br />

fax 661/587-5031 or e-mail us from our website<br />

www.strategyandtacticspress.com.<br />

NON U.S. SUBSCRIBERS PLEASE NOTE: Surface<br />

mail to foreign addres ses may take six to ten<br />

weeks for delivery. Inquiries should be sent to<br />

Decision Games after this time, to P.O. Box 21598,<br />

Bakersfield CA 93390.<br />

STRATEGY & TACTICS ® is a registered trademark<br />

for Decision Games’ military history magazine.<br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> & <strong>Tactics</strong> (©2007) reserves all rights<br />

on the contents <strong>of</strong> this publication. Nothing may<br />

be reproduced from it in whole or in part without<br />

prior permission from the publisher. All rights<br />

reserved. All correspondence should be sent<br />

to decision Games, P.O. Box 21598, Bakersfield<br />

CA 93390.<br />

STRATEGY & TACTICS (ISSN 1040-886X) is published<br />

bi-monthly by Decision Games, 1649 Elzworth St. #1,<br />

Bakersfield CA 93312. Periodical Class postage paid<br />

at Bakersfield, CA and additional mailing <strong>of</strong>fices.<br />

address Corrections: address change forms to<br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> & <strong>Tactics</strong>, PO Box 21598, Bakersfield CA<br />

93390.<br />

4 #245<br />

coNTENTS<br />

F E A T U R E S<br />

6 <strong>The</strong> Guerra Grande: <strong>The</strong> War <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Triple Alliance, 1865-70<br />

Paraguay takes on South America in one <strong>of</strong> the 19 th century’s<br />

bloodiest conflicts.<br />

by Javier romero Munoz<br />

20 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>France</strong>, <strong>1940</strong>: Myths & Reality<br />

<strong>The</strong> story behind one <strong>of</strong> the most stunning campaigns <strong>of</strong> the 20 th<br />

century.<br />

by John Burtt

F E A T U R E S<br />

RULES<br />

R1 TRipLE ALLiANcE WAR<br />

by Javier romero<br />

coNTENTS<br />

38 <strong>The</strong> Art <strong>of</strong> War in the Middle Ages:<br />

A Survey<br />

A millennia <strong>of</strong> mayhem from the <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>of</strong> Rome to the<br />

Renaissance <strong>of</strong> Infantry.<br />

by albert N<strong>of</strong>i<br />

50 Tactical File: Gonzalvo de cordoba<br />

& the Battle <strong>of</strong> the Garigliano<br />

<strong>The</strong> Spanish win a battle as a wily general takes his<br />

place as a great captain.<br />

by albert N<strong>of</strong>i<br />

54 US Army Transformation<br />

for Future War<br />

<strong>The</strong> Pentagon re-tools in order to fight both the next war and<br />

engage today’s unconventional foes.<br />

by William stroock<br />

dEpARTMENTS<br />

31 for your information<br />

nuclear Winter Possibilities<br />

by David Lentini<br />

the 2006 War in Lebanon<br />

by William Stroock<br />

Siam in World War i<br />

by Brendan Whyte<br />

number 245<br />

august/September 2007<br />

36 ThE LoNG TRAdiTioN<br />

37 WoRkS iN pRoGRESS<br />

strategy & tactics 5

6 #245<br />

<strong>The</strong> Guerra Grande:<br />

<strong>The</strong> War <strong>of</strong> the Triple Alliance, 1865-1870<br />

While the American Civil was coming to its<br />

conclusion in April 1865, the Paraguayan<br />

Army invaded the Argentinean province <strong>of</strong><br />

Corrientes, thus unleashing the most devastating<br />

war ever seen in South America. This war<br />

changed forever all the countries involved: Argentina<br />

emerged as a unified nation; the Brazilian<br />

Empire was put on the path to becoming<br />

a republic, Paraguay lost an estimated 80% <strong>of</strong><br />

its male population, and Uruguay was forever<br />

recognized as an independent country by its<br />

neighbours. <strong>The</strong> war left a lasting impression<br />

in the folklore and heritage <strong>of</strong> all involved,<br />

especially among the Paraguayans, who even<br />

today remember with pride the epic <strong>of</strong> their<br />

Guerra Grande: “ Great War.”<br />

By: Javier Romero Muñoz<br />

Early Moves: <strong>The</strong> Matto Grosso Sideshow<br />

In December 1864 a combined ground/riverine<br />

Paraguayan expeditionary force departed Asunción<br />

to conquer the Brazilian province <strong>of</strong> Matto Grosso, in<br />

dispute between the two countries since colonial times.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Paraguayans figured they could steal a march.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re were few Brazilian troops in the Matto Grosso<br />

because reinforcements had to follow the Parana-Paraguay<br />

riverine route and pass across the Paraguayan<br />

port <strong>of</strong> Asunción. In fact, the Matto Grosso wilderness<br />

was so remote from Brazil that, when the Brazilians<br />

later sent an expeditionary force to march across the<br />

land route it took them nearly two years to reach the<br />

Paraguayan border.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Paraguayan expeditionary force (3,500 infantry<br />

embarked in five ships along with 2,500 cavalry<br />

and 800 infantry going by land) quickly secured the<br />

Brazilian post <strong>of</strong> Fort Coimbra and blocked naviga-

tion in the Upper Paraguay River. <strong>The</strong>y also captured<br />

the Matto Grosso’s capital, Corumbá. In April 1865<br />

the Paraguayans reached Coxim, their farthest point <strong>of</strong><br />

advance. After leaving some 1,000 men in garrisons,<br />

the expedition returned to Asunción by mid-1865.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Matto Grosso expedition was useful for the<br />

Paraguayans because they captured large numbers <strong>of</strong><br />

cattle (for feeding the troops) and also large quantities<br />

<strong>of</strong> ammunition. <strong>The</strong> occupation seemed to have<br />

settled all territorial claims by Paraguay. <strong>The</strong> next step<br />

was to march to Uruguay and secure that country’s<br />

independence. To do so, the Paraguayans needed Argentina<br />

to grant passage for their army across roughly<br />

100 miles <strong>of</strong> the Argentine province <strong>of</strong> Misiones. Paraguayan<br />

President López asked Argentine President<br />

Mitre, but Mitre, who had granted the Brazilians free<br />

passage to blockade the Uruguayan ports during their<br />

intervention in that country, rebuffed López’s request.<br />

López, convinced that the rebel Argentine province<br />

<strong>of</strong> Entre Ríos would support him against Mitre in case<br />

<strong>of</strong> a war against Paraguay, declared war on Argentina<br />

in March. In May, the governments <strong>of</strong> Argentina,<br />

Brazil and Uruguay signed a treaty <strong>of</strong> alliance that included<br />

a secret protocol that distributed large chunks<br />

<strong>of</strong> Paraguayan territory between Argentina and Brazil.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Triple Alliance War had begun.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Invasion <strong>of</strong> Corrientes<br />

<strong>The</strong> Paraguayans needed to act quickly before their<br />

enemies could mobilize their vast resources. By May<br />

the Paraguayan army had some 60,000 troops in the<br />

field, <strong>of</strong> which some 30,000, forming the Army <strong>of</strong> the<br />

South, were set to invade the Argentine province <strong>of</strong><br />

Corrientes. That army had two columns: the main<br />

force (Division <strong>of</strong> the Paraná, with 14,000 infantry,<br />

6,000 cavalry, 30 guns and the support <strong>of</strong> the Paraguayan<br />

Navy), under Gen. Robles took the riverine<br />

port <strong>of</strong> Corrientes and advanced down the Paraná<br />

River. A supporting force, under Lt. Gen. Estigarribia<br />

(Division <strong>of</strong> the Uruguay with 7,000 infantry, 3,000<br />

horse, and five guns), would advance from Candelaria<br />

to Uruguay.<br />

Both columns advanced deep into Argentina hoping<br />

to stir up a new provincial rebellion. <strong>The</strong> Paraguayans<br />

planned to also enter Uruguay and revive the Blanco<br />

cause there. Both Paraguayan columns followed the<br />

course <strong>of</strong> the rivers Paraná and Uruguay, using them<br />

as line <strong>of</strong> communication since the road net in the area<br />

was abysmal and the ground was covered mostly by<br />

marshlands called esteros.<br />

When news <strong>of</strong> the Paraguayan invasion reached<br />

Buenos Aires, Mitre immediately ordered mobilization.<br />

He regrouped 30,000 men <strong>of</strong> the regular army<br />

and the Guardia Nacional militia, sending all available<br />

troops to the north to counter the Paraguayans.<br />

Aside from a few local irregular militia, the only<br />

sizeable force at hand to stop the Paraguayans were<br />

the 17 ships (with 103 guns) <strong>of</strong> the 2nd and 3rd Divisions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Brazilian fleet; though in a campaign fought over<br />

riverine lines <strong>of</strong> communication, the Brazilian fleet was a<br />

force to be reckoned with. Another positive event for the<br />

Argentines was that the <strong>of</strong>ten rebellious provinces <strong>of</strong> Corrientes<br />

and Entre Ríos rallied to the cause. Despite López’s<br />

hopes, they did not join the Paraguayan cause—though in<br />

the event <strong>of</strong> a major Argentine defeat they might have been<br />

convinced to switch sides.<br />

Riachuelo and Uruguayana<br />

After the Division <strong>of</strong> the Paraná advanced to the city <strong>of</strong><br />

Goya, the Argentines counterattacked by landing at Corrientes<br />

and taking that city in a mere 24 hours on 25 May.<br />

Corrientes was the main rear depot <strong>of</strong> the Division <strong>of</strong> the<br />

strategy & tactics 7

8 #245<br />

Geography <strong>of</strong> the Paraguayan War: <strong>The</strong><br />

Chaco, the Paraneña and the Matto Grosso<br />

<strong>The</strong> Paraguayan War was fought over three main natural<br />

regions: the Paraneña (the Paraguayan heartland), the<br />

Matto Grosso, and the Chaco. <strong>The</strong> Paraneña can be generally<br />

described as a mixture <strong>of</strong> plateaus, rolling hills and valleys,<br />

with highlands in the east that slope toward the Río Paraguay<br />

and becomes an area <strong>of</strong> lowlands and marshes (called esteros in<br />

that region <strong>of</strong> the world). It is subject to floods along the Paraguay<br />

River. <strong>The</strong> easier and most logical invasion route <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Paraneña region was across the Paraná River at Itapúa and on<br />

to the rolling hills to the east. <strong>The</strong> war, however, was fought in<br />

the jungles and marshes around the junction between the Parana<br />

and Paraguay rivers, the main transport and communication<br />

routes in the area. Those two rivers were defended by the<br />

Humaita fortress, called “the Sevastopol <strong>of</strong> South America.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> Allies took the <strong>of</strong>fensive there because it allowed them to<br />

employ the support <strong>of</strong> the powerful Brazilian fleet, despite the<br />

possibility <strong>of</strong> losing valuable ships running aground on shifting<br />

sandbars.<br />

<strong>The</strong> actual area <strong>of</strong> operations was basically an unmapped<br />

swamp, infested by snakes, caymans and assorted other hostile<br />

fauna. It had little in the way <strong>of</strong> trails, with little or no<br />

grass that the cavalry could use for grazing. (<strong>The</strong> Allied cavalry<br />

lost most <strong>of</strong> its mounts within months <strong>of</strong> operating in that<br />

area.) <strong>The</strong>re were also tropical diseases. <strong>The</strong> long duration <strong>of</strong><br />

the siege <strong>of</strong> Humaita caused the appearance <strong>of</strong> cholera that<br />

caused thousands <strong>of</strong> deaths among the Allied troops. <strong>The</strong> Parana<br />

and Paraguay Rivers and their tributaries overflowed during<br />

the rainy season, causing severe flooding because <strong>of</strong> the almost<br />

impervious clay subsurface that prevents the absorption <strong>of</strong> excess<br />

surface water into the aquifer.<br />

Across the western bank <strong>of</strong> the Paraguay is the Chaco. <strong>The</strong><br />

Chaco is an immense piedmont plain, almost perfectly flat,<br />

with a few elevations <strong>of</strong> 125 meters and no more than 300.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Chaco is a mixture <strong>of</strong> desert and jungle, with the worst<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> both. When the Allies decided to build a road on the<br />

Chaco side <strong>of</strong> the Paraguay River, it took them three months<br />

to build a five mile road. <strong>The</strong> Chaco has a hostile climate to<br />

boot, with temperatures <strong>of</strong> up to 115º F in summer. In 1860 the<br />

Chaco was inhabited by hostile tribes such as the Mocovíes<br />

or the Guacurús, who had regularly raided Paraguayan settlements<br />

since colonial times. <strong>The</strong>y took advantage <strong>of</strong> Paraguayan<br />

troops being deployed elsewhere to renew for those raids.<br />

Just northeast <strong>of</strong> the Paraguayan heartland was the area disputed<br />

with Brazil, the Matto Grosso. It is an immense plateau<br />

formed by the highlands <strong>of</strong> the interior between the Amazonas<br />

and the basins <strong>of</strong> the rivers running south (the Paraguay, Parana<br />

and tributaries). Not unsurprisingly, “Matto” means “thick forest,”<br />

and Grosso means “very big.” Like most <strong>of</strong> Amazonia,<br />

the Matto Grosso is characterized by impenetrable forests and<br />

all types <strong>of</strong> hostile forms <strong>of</strong> fauna, from snakes and disease<br />

carrying mosquitoes to jaguars, caymans, etc. <strong>The</strong> primary<br />

and usually only method <strong>of</strong> transport and communication was<br />

(is) riverine craft. In 1864 the bulk <strong>of</strong> the Paraguayan invasion<br />

forces arrived via riverines, with supporting forces entering<br />

the area using the few roads. <strong>The</strong> Matto Grosso was so remote<br />

that, when the Brazilians sent a small expedition from Río de<br />

Janeiro to reconquer the region occupied by the Paraguayans,<br />

it took them two full years to arrive.<br />

Paraná. Seeing his lines <strong>of</strong> communication menaced,<br />

an alarmed López ordered Robles’ Division to retreat<br />

back to Corrientes. Before continuing the advance he<br />

also wanted to secure control <strong>of</strong> the Paraná River by<br />

defeating a sizeable part <strong>of</strong> the imperial Brazilian fleet<br />

before it could unite with its reserves (seven warships)<br />

still at the mouth <strong>of</strong> the River Plate.<br />

On 11 June at Riachuelo, a Paraguayan squadron<br />

<strong>of</strong> nine vessels with 30 guns (all but one ship were<br />

unprotected armed merchants) and six chatas (armed<br />

barges) tried to lure the Brazilian squadron (nine warships,<br />

60 guns) into a trap where they would be forced<br />

to fight within close range <strong>of</strong> a Paraguayan artillery<br />

battery <strong>of</strong> 22 guns and 2,000 riflemen. That ruse, along<br />

with Paraguayan boarding parties who stormed several<br />

enemy ships, almost gave victory to López’s forces.<br />

But almost wasn’t enough. <strong>The</strong> Brazilian armored<br />

frigate Amazona decided the outcome by sinking several<br />

Paraguayan vessels with its steel ram.<br />

With the Paraná river secured by the Allies, the<br />

main Paraguayan force had been halted in its tracks;<br />

however, Estigarribia’s Division <strong>of</strong> the Uruguay continued<br />

the advance, being harassed only occasionally<br />

by some irregular cavalry militia. López probably<br />

hoped the Blancos would rise in arms again if his<br />

troops entered Uruguay, and he also expected a rebellion<br />

<strong>of</strong> Brazilian slaves.<br />

Estigarribia’s command was divided into two columns,<br />

one west <strong>of</strong> the Uruguay river and one east <strong>of</strong><br />

it. His western force was defeated by the Argentine<br />

1st Division reinforced by a Uruguayan brigade at the<br />

Battle <strong>of</strong> Yataití-Corá (17 August). <strong>The</strong> defeat <strong>of</strong> the<br />

covering force left Estigarribia almost isolated from<br />

his base in Paraguay. Instead <strong>of</strong> retreating north (probably<br />

because, like most Paraguayan commanders, he<br />

was too wary <strong>of</strong> López to act without orders), he occupied<br />

the Brazilian town <strong>of</strong> Uruguayana, where he<br />

was surrounded by a combined Argentine-Uruguayan-<br />

Brazilian force.<br />

Starvation finally forced Estigarribia to surrender<br />

on 18 September 1865. <strong>The</strong> fall <strong>of</strong> Uruguayana was<br />

a major disaster for the Paraguayan cause, since the<br />

troops lost there could not be replaced and would be<br />

sorely needed during the upcoming Allied counterinvasion.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Allied Counter-<strong>of</strong>fensive: Plans for the<br />

Invasion<br />

Abysmal communications and rainy weather prevented<br />

the main Allied forces from reaching the city <strong>of</strong><br />

Corrientes until November 1865. <strong>The</strong> Paraguayan Division<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Paraná was now under command <strong>of</strong> Col.<br />

Resquín—Robles had been recalled to Asunción and<br />

shot on López’s orders. Resquín’s men managed an<br />

orderly retreat back to Paraguay, bringing with them<br />

all the cattle they could commandeer.<br />

continued on page 10

March to War: Post-Colonial Río de la Plata<br />

In 1807 insurrections broke out in the Spanish Empire’s<br />

South American colonies. In accordance with the liberal and<br />

nationalist beliefs <strong>of</strong> the day, those colonies demanded independence.<br />

<strong>The</strong> insurrection was led by men such as Simon<br />

Bolivar and José de San Martin, and by 1825 the colonies<br />

had all established their indpendence from the once-mighty<br />

empire.<br />

<strong>The</strong> four-decade period that followed witnessed a slow<br />

and <strong>of</strong>ten bloody process <strong>of</strong> nation building in the countries<br />

that once formed the Viceroyalty <strong>of</strong> La Plata: Argentina, Uruguay,<br />

Paraguay, and Bolivia. <strong>The</strong> criollo (American-born<br />

Spaniards) elites from Buenos Aires, who led Argentina’s<br />

revolt against Spain, saw themselves as the natural rulers <strong>of</strong><br />

the territories that once formed the viceroyalty; however, in<br />

the provinces the local elites thought otherwise. <strong>The</strong>y were<br />

not eager to substitute Spanish domination for Argentinean.<br />

Bolivia and Paraguay began to break away from the authority<br />

<strong>of</strong> Buenos Aires as early as 1810, and the Banda Oriental<br />

(“Eastern Side,” the Spanish territories East <strong>of</strong> the Río de la<br />

Plata, later known as Uruguay) in 1816. In fact, the Paraguayans<br />

had to fight for independence against Buenos Aires, not<br />

against Spain. In January 1811, an Argentine force was sent<br />

to Asunción to “invite” the Paraguayans to recognize Buenos<br />

Aires’ authority. <strong>The</strong> Paraguayan militia routed that force at<br />

the Battle <strong>of</strong> Paraguarí.<br />

Argentinean nationalism, in the sense <strong>of</strong> the people believing<br />

themselves to be all part <strong>of</strong> a single group, was not<br />

well developed. <strong>The</strong> city and province <strong>of</strong> Buenos Aires included<br />

almost half the Argentine population, and they saw<br />

themselves as the rulers <strong>of</strong> the provinces. That was not too<br />

far from the wars <strong>of</strong> German and Italian unification that were<br />

happening at about the same time in Europe.<br />

Brazil was a huge empire where national unity was weak<br />

at best. <strong>The</strong> people spoke different dialects, had different traditions<br />

and, despite the country’s huge wealth, could not mobilize<br />

as a single entity.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Hermit Kingdom: Paraguay, 1816-1864<br />

Of all the territories <strong>of</strong> the former Viceroyalty <strong>of</strong> the River<br />

Plate, Paraguay was the only one that could be described as a<br />

nation-state in 1810. Its people had a strong sense <strong>of</strong> national<br />

identity ever since colonial times, probably because they had<br />

been a frontier zone continuously at war against both Portuguese-Brazilian<br />

encroachments in the Misiones territory, as<br />

well as having to fight against hostile Indians from the Chaco.<br />

In Paraguay a different model <strong>of</strong> colonial society developed,<br />

in a sense more Indian than Spanish. <strong>The</strong> Spanish established<br />

a relationship with the local Guaraní peoples that was closer<br />

to an alliance than to the usual colonial domination.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Paraguayan political and economic systems remained<br />

different from the Argentine during the post-colonial period.<br />

After gaining independence, Paraguay, under the dictatorship<br />

<strong>of</strong> Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia, known as El Supremo<br />

(1814-40), and later <strong>of</strong> Carlos A. López (1840-62), became<br />

a “hermit kingdom,” a kind <strong>of</strong> semi-legendary landlocked<br />

state, completely isolated from the outside world and hence<br />

from the surrounding turmoil. Francia also eliminated all race<br />

differences by forcing the criollos to inter-marry with Guarani<br />

women, thus creating the most homogeneous population<br />

Under Carlos A. López, Paraguay was opened to foreign<br />

trade and the economy was strictly controlled by the state.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re was no free trade, nor liberal democracy, but many<br />

contemporary observers favorably compared the peace and<br />

stability <strong>of</strong> Paraguay with the chaos and civil war <strong>of</strong> its<br />

neighbors.<br />

Carlos A. López was succeeded by his son, Francisco<br />

Sloan López, who decided to give Paraguay a proud place<br />

among nations. <strong>The</strong> Uruguayan civil war was to be the opportunity<br />

to become a power in the Plata.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Uruguayan Powder Keg<br />

Uruguay had been a war zone between the rival empires<br />

<strong>of</strong> Spain and Portugal during most <strong>of</strong> the colonial era. <strong>The</strong><br />

Portuguese regarded it as a Spanish bridgehead in the eastern<br />

River Plate. Until well into the 19 th century the Brazilians<br />

claimed it as part <strong>of</strong> the their empire.<br />

Like Argentina, post-colonial Uruguay was regularly<br />

wracked by civil wars. <strong>The</strong> elites <strong>of</strong> Montevideo fought the<br />

rural elites, represented by the Colorado and Blanco parties,<br />

respectively. In 1864 the Colorados rose in rebellion against<br />

the ruling Blancos. <strong>The</strong> Brazilian state <strong>of</strong> Rio Grande do Sul,<br />

a major force in Brazilian politics, as most <strong>of</strong> the empire’s<br />

military <strong>of</strong>ficers came from there, supported the Colorados.<br />

Since Brazil militarily supported the Colorados, the ruling<br />

Blancos sought an alliance with López’s Paraguay.<br />

It seems clear López was influenced by the European<br />

concept <strong>of</strong> balance <strong>of</strong> power. He had travelled in Europe<br />

in the 1850s, and was also a great admirer <strong>of</strong> Napoleon III,<br />

then emperor <strong>of</strong> <strong>France</strong>. López probably saw the Brazilian<br />

intervention against Uruguay as the first step to annex their<br />

claimed “isolated province,” to be followed by the partition<br />

<strong>of</strong> Paraguay between Argentina and Brazil. <strong>The</strong>re were<br />

also border demarcation issues between all those countries,<br />

mostly because the colonial era borders were never clearly<br />

defined.<br />

All those factors led López to establish an alliance with<br />

the ruling Uruguayan faction, and to issue an ultimatum to<br />

Brazil that any intervention in Uruguay would be regarded<br />

as casus belli. Despite the ultimatum, a Brazilian expeditionary<br />

force entered Uruguay in October 1864 in support <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Colorados. López retaliated by seizing a Brazilian merchant<br />

steamer, the Marquis de Olinda, on 12 November, thus starting<br />

the Triple Alliance War.<br />

in all <strong>of</strong> South America. Contemporary picture <strong>of</strong> the tri-border area.<br />

strategy & tactics 9

10 #245<br />

By early autumn 1866 (remember, this is the southern<br />

hemisphere, fall begins in March, winter in June)<br />

the Allies were ready to invade Paraguay. <strong>The</strong>y had<br />

some 60,000 Argentine, Uruguayan and Brazilian<br />

troops plus some 30 ships, four <strong>of</strong> them state-<strong>of</strong>-theart<br />

ironclads. <strong>The</strong> Allies choose to cross at the junction<br />

between the Paraná and Paraguay rivers because<br />

it allowed them to fight under cover <strong>of</strong> the artillery<br />

<strong>of</strong> the imperial fleet. Instead <strong>of</strong> following the more<br />

logical route across the Paraná at Itapúa and over dry<br />

ground on to Asunción, the same route followed by<br />

the Argentines in 1811, the Allies planned to fight in<br />

the unmapped swamps and marshlands <strong>of</strong> the Paraná<br />

River area. <strong>The</strong>y saw an advantage in using the Paraná<br />

and Paraguay rivers as lines <strong>of</strong> communication. Via<br />

the waterways they could bring up men and supplies,<br />

as well as moving quickly via riverine shipping.<br />

A major obstacle lay, however, between the Paraguayan<br />

capital and the Allied forces: the massive<br />

fortress at Humaitá, with some 180 guns, closing the<br />

navigation <strong>of</strong> the river. <strong>The</strong>re was also the defensive<br />

terrain around Humaitá, with unmapped marshes, jungles<br />

and swamps. <strong>The</strong> Allied plan was to take Humaitá<br />

by land and then launch a secondary thrust across the<br />

Paraná from Itapúa with some 13,000 troops—then on<br />

to Asunción. An <strong>of</strong>fensive away from the river could<br />

exploit the better terrain for marching, but would lack<br />

the support <strong>of</strong> the navy. Lines <strong>of</strong> communication would<br />

be overland and vulnerable to enemy cavalry raids.<br />

Troops in the field—Uraguay, 1866.<br />

While the Allies continued their build-up, enthusiasm<br />

for the war among the Brazilian and Argentine<br />

people waned. <strong>The</strong> people <strong>of</strong> the provinces <strong>of</strong> Corrientes<br />

and Entre Ríos, especially, saw a Paraguayan<br />

defeat as consolidating the Buenos Aires hegemony<br />

within the republic. Despite their eroding political<br />

base, however, the Allies attacked.<br />

Paso de Patria to Curupaytí<br />

In April 1866, the Allied force marched into Paraguay<br />

at Paso de Patria, embarked on 65 steamers and<br />

50 sailing vessels. Thus began the long approach<br />

march to the fortress <strong>of</strong> Humaitá.<br />

During the initial stages <strong>of</strong> the campaign, López<br />

squandered some <strong>of</strong> his finest troops by launching several<br />

frontal attacks: at Estero Bellaco (12 May) and<br />

First Tuyutí (24 May). <strong>The</strong> Paraguayans lost some<br />

17,000 men killed or wounded, inflicting in exchange<br />

only 5,000 casualties. <strong>The</strong> Allies showed that superior<br />

firepower and modern artillery could overcome the<br />

most fanatic <strong>of</strong> assaults. <strong>The</strong> Allies could replace their<br />

losses, while López could not.<br />

After fending <strong>of</strong>f the Paraguayan attacks, the Allied<br />

army faced the extensive earthwork system known as<br />

the Lines <strong>of</strong> Rojas. <strong>The</strong>y had been prepared by George<br />

Thompson, among others. Thompson was a British<br />

engineer in the service <strong>of</strong> the Paraguayan army.<br />

During July the Allies lost more than 2,000 men<br />

while trying to break the Paraguayan trenches. Finally,<br />

Mitre deemed the Allied forces were not strong enough

to breach the Rojas Line, so he halted while waiting<br />

for reinforcements. Given the superiority in cavalry <strong>of</strong><br />

the Paraguayans, Mitre had to order the Paso de Patria<br />

encampment be fortified to protect the depot from<br />

raiders and also to have a solid base in case <strong>of</strong> retreat.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Brazilian II Corps concentrated at Itapúa for<br />

a secondary thrust on Asunción and would reinforce<br />

the Allied army in front <strong>of</strong> the Rojas Line. Other units<br />

<strong>of</strong> that corps would land at Curuzú, south <strong>of</strong> Humaitá,<br />

and advance on the fortress following the course <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Paraná with the support <strong>of</strong> the navy’s guns.<br />

In early September an Allied force landed at Curuzú,<br />

taking it by assault. For the first and only time<br />

in the war, a Paraguayan battalion, the 10th , fled, and<br />

was disbanded and decimated on López’s orders. On<br />

22 September, when 10,000 Brazilians and 9,000 Argentines<br />

tried to take the entrenchments at Curupaytí<br />

by frontal assault, as the last step before reaching the<br />

outer ring <strong>of</strong> the Humaitá fortress, disaster struck. Despite<br />

the support <strong>of</strong> 101 naval guns firing more than<br />

5,000 shells, the Allies lost 4,000 men and failed to<br />

take the entrenchments. <strong>The</strong> Paraguayans’ seven infantry<br />

battalions and four cavalry regiments lost fewer<br />

than 100 men.<br />

After hearing news <strong>of</strong> Curupaytí, morale plummeted<br />

on the Allied home front. <strong>The</strong> Argentine province<br />

<strong>of</strong> Mendoza rose in rebellion against the Buenos<br />

Aires government, followed by Rosario Province. <strong>The</strong><br />

already depleted Allied armies had to send 15 Argentine<br />

battalions to quell the rebellion. Mitre himself<br />

was soon forced to relinquish his command in order to<br />

direct operations against the rebels. <strong>The</strong> Uruguayans<br />

also had to face similar problems at home.<br />

In sum, the fighting stalemated for nearly a year<br />

while the Allies recovered from their losses and dealt<br />

with their internal problems. Operating for so many<br />

months in the marsh area was taking its toll in the form<br />

<strong>of</strong> diseases such as cholera. Horses were also dying<br />

for lack <strong>of</strong> pasture. To make things worse, the terms <strong>of</strong><br />

the Treaty <strong>of</strong> the Triple Alliance were made public, revealing<br />

the dismemberment <strong>of</strong> Paraguay was an objective.<br />

That revelation unleashed a diplomatic uproar, a<br />

wave <strong>of</strong> sympathy for the Paraguayan cause in Europe<br />

and America, and further stiffened the Paraguayans’<br />

will to fight.<br />

With the Argentines and Uruguayans busy with<br />

their respective home fronts, the war was becoming<br />

increasingly a Paraguayan-Brazilian affair. With all<br />

that in mind, Brazilian Marshall Caxias took command<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Allied army in February 1867.<br />

<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>of</strong> Humaitá<br />

In June 1867, the Allies renewed <strong>of</strong>fensive operations<br />

by launching the Tuyú Cué maneuver. Brazilian<br />

III Corps had been raised to substitute for the Argentine<br />

troops sent home to put down the provincial rebellions.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Allied fleet was also reinforced to 10 iron-<br />

Troops in the field—Uraguay, 1866.<br />

clads plus 33 other warships, with 223 guns total.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Allied plan for the 1867 campaign was to outflank<br />

the Lines <strong>of</strong> Rojas from the east, thus isolating<br />

the fortress <strong>of</strong> Humaitá. With the help <strong>of</strong> US observation<br />

balloonists contracted by the Brazilians, the Allies<br />

mapped the area, identifying weak spots in the Paraguayan<br />

lines. In July, Allied forces (some 45,000 men,<br />

all Brazilians save 5,000 Argentines and a few hundred<br />

Uruguayans) attacked and outflanked the Lines <strong>of</strong><br />

Rojas. <strong>The</strong> Paraguayans, down to 20,000 men, abandoned<br />

their positions and retreated toward Humaitá.<br />

Finally, the Allies cut land communications and the<br />

telegraph line between Asunción and Humaitá. During<br />

September-November 1867, the Allies consolidated<br />

their control <strong>of</strong> the eastern bank <strong>of</strong> the Paraguay.<br />

<strong>The</strong> idea was to move the main line <strong>of</strong> communication<br />

Wars <strong>of</strong> the Imperial Age, South American Style<br />

<strong>The</strong> Triple Alliance War was a mixture <strong>of</strong> old and new. Like the<br />

American Civil War, the Triple Alliance War was an early example <strong>of</strong><br />

total war. Though Paraguay was not an industrialized country, the war<br />

effort required a massive mobilization <strong>of</strong> resources over five years. That<br />

was possible only because Paraguayan nationalism generated an intense<br />

will to fight to the finish.<br />

<strong>The</strong> war saw some <strong>of</strong> the first examples <strong>of</strong> the emerging military<br />

technology: monitors, armored ships, observation balloons, and above<br />

all, trenchlines. As one author put it though, “<strong>The</strong> Paraguayan War was<br />

[also] a war <strong>of</strong> poor old flintlocks against La Hittes and Withworths, and<br />

<strong>of</strong> ironclads against canoes.” Certainly the same determination to fight to<br />

the end regardless <strong>of</strong> cost would be seen again in the World Wars.<br />

Increasing firepower began to dominate the battlefields. Despite the<br />

élan and fanaticism <strong>of</strong> the Paraguayans, Allied weaponry <strong>of</strong>ten carried<br />

the day. And when the Allies tried to attack Paraguayan trenches, they<br />

also got shot to ribbons.<br />

As in the American Civil War, military commanders on both sides<br />

were equally shocked by the new military realities. <strong>The</strong> commanders<br />

expected Napoleonic-like campaigns <strong>of</strong> movement with a few decisive<br />

battles. South Americans were used to fighting battles in which lance-<br />

and saber-armed cavalry were the decisive weapons. Instead, most commanders<br />

did not have the capability to develop new tactics. Only the Brazilians,<br />

who had a pr<strong>of</strong>essional <strong>of</strong>ficer corps, showed some ingenuity.<br />

strategy & tactics 11

12 #245<br />

Military Commanders <strong>of</strong> the Triple Alliance War<br />

Francisco Sloan López (1826-1870). Dictator for life <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Paraguayan Republic, Sloan López was influenced by the<br />

European concept <strong>of</strong> balance <strong>of</strong> power. He changed<br />

the traditional Paraguayan foreign policy and tried<br />

to intervene in the politics <strong>of</strong> El Plata, leading his<br />

country into the Triple Alliance War. His conduct<br />

<strong>of</strong> the war was a disaster: he squandered<br />

Paraguay’s best troops during its early stages,<br />

first during the invasion <strong>of</strong> Argentina and later<br />

launching frontal assaults against the Allied<br />

forces at Tuyutí and Estero Bellaco. He kept his<br />

commanders on a short rein, and they did not<br />

dare show initiative. Purges were rife in the Paraguayan<br />

Army, especially toward the end <strong>of</strong> the<br />

war. <strong>The</strong> Argentine press dubbed him “Tropical<br />

Caligula” among other things. For instance, after<br />

the 10 th battalion fled from combat, López ordered<br />

the unit “decimated” and disbanded, the survivors being<br />

distributed among other units. He also had his mother<br />

and other relatives shot, fearing they would betray him.<br />

Bartolomé Mitre (1821-1906). In 1862 Mitre was elected president<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Argentine Confederacy after a long series <strong>of</strong> civil<br />

wars. At the treaty <strong>of</strong> the Triple Alliance, Brazil and Argentina<br />

agreed to give Mitre overall command <strong>of</strong> the Allied land<br />

forces (the Brazilians would command the navy). After the<br />

disaster at Curupaytí in 1867, however, internal unrest in Argentina<br />

forced Mitre to leave that post. Also, the fact Mitre<br />

was commander-in-chief caused no small amount <strong>of</strong> friction<br />

with the Brazilians, because they were doubtful he could effectively<br />

command large units in the field. In 1868 Mitre lost<br />

the election to Domingo Sarmiento, who intended to reduce<br />

Argentina’s participation in the war.<br />

Marshall Luis Alves de Lima, Duke <strong>of</strong> Caxias<br />

(1803-1880). After the disaster <strong>of</strong> Curupaytí,<br />

Caxias took command <strong>of</strong> the Allied army in<br />

Paraguay. His strategy was more methodical<br />

and pr<strong>of</strong>essional than that <strong>of</strong> Mitre. He favored<br />

a slower approach, first surrounding<br />

Humaitá before conquering it and continuing<br />

the advance up the Paraguay River.<br />

His brilliant manoeuvre at El Chaco<br />

reduced Allied casualties. After the fall<br />

<strong>of</strong> Asunción, Caxias deemed the war<br />

over and resigned from command.<br />

<strong>The</strong> last reserves:<br />

Paraguayan child soldier.<br />

from the Paso da Patria-Tuyutí axis to the Paraguay<br />

River. Also, the forces north <strong>of</strong> Humaitá would have<br />

to be supplied across the Paraguay, and therefore the<br />

Allied fleet would have to force the Humaitá pass.<br />

<strong>The</strong> besieged Paraguayans launched a spoiling attack<br />

(Second Battle <strong>of</strong> Tuyutí, November 1867) that<br />

managed to take the Allies by surprise. But precious<br />

time was wasted while the troops looted Allied depots,<br />

giving the Allies time to bring in reinforcements and<br />

win the battle. <strong>The</strong> Paraguayans lost some 4,000 men<br />

against some 2,000 Allied casualties.<br />

On 15 February 1868 a Brazilian force <strong>of</strong> three<br />

ironclads and three monitors, the latter built especially<br />

for operations here, forced the Humaitá pass without<br />

losing a single ship, even though they took some 350<br />

hits. <strong>The</strong> Brazilian squadron shelled Asunción two<br />

days later, prompting López to order the evacuation <strong>of</strong><br />

continued on page 14

<strong>The</strong> Opposing Armies<br />

<strong>The</strong> Paraguayans<br />

<strong>The</strong> Paraguayans (also known as “Guaraníes”) were (are) one<br />

<strong>of</strong> the most integrated nations in all <strong>of</strong> South America. In the Paraguayan<br />

Army there were no significant race or class differences. All<br />

the population was formed by Guaraní Indians or people <strong>of</strong> mixed<br />

Spanish-Guaraní blood. Also, all able-bodied men were required to<br />

serve in the army, regardless <strong>of</strong> class or race.<br />

All that gave the Paraguayans a sense <strong>of</strong> nationhood far more<br />

developed than that <strong>of</strong> their enemies, and led them to fight fanatically<br />

to the bitter end. Unlike the situation in most South American wars,<br />

the Paraguayans were not fighting for control <strong>of</strong> one remote region in<br />

the wilderness. <strong>The</strong>y were fighting for national survival: what was at<br />

stake was the existence <strong>of</strong> Paraguay as an independent nation.<br />

At the start <strong>of</strong> the war, the Paraguayan army deployed 60-80,000<br />

troops out <strong>of</strong> a population <strong>of</strong> some 800,000 people. That was virtually<br />

every available man in the country. <strong>The</strong>re was no reserve left. <strong>The</strong><br />

best men were assigned to the cavalry and artillery.<br />

Infantry was organized into 48 battalions, numbered 1 to 48.<br />

Some elite units received names such as the 40th “Asunción” Battalion<br />

or the 6th and 7th Sapper battalions, the Ñembi-i. Each battalion<br />

deployed from 720 to 1,000 men organized in eight companies (six<br />

line infantry, one grenadier, one light infantry or “cazadores”—all<br />

very Napoleonic sounding). Cavalry deployed 20 to 25 regiments.<br />

<strong>The</strong> artillery was organized into 12 horse batteries and seven foot<br />

batteries. <strong>The</strong>re was also a small riverine navy. All ships but one (the<br />

Tacuarí, armed with four 24 pounders and two 32 pounders) were<br />

armed merchantmen. <strong>The</strong> Paraguayans made much use <strong>of</strong> chatas,<br />

barges armed generally with a single 8” iron gun. <strong>The</strong> chatas were<br />

usually deployed at the river banks, under cover <strong>of</strong> field/fortress artillery<br />

and protected by “torpedoes,” that is boxes <strong>of</strong> explosives with<br />

percussion fuses.<br />

Weapons varied greatly in quality, but in general the Paraguayans<br />

deployed obsolete cast-<strong>of</strong>fs along with the occasional modern<br />

weapon. <strong>The</strong> average infantry battalion used Brown Bess flintlocks,<br />

though seven <strong>of</strong> the infantry battalions used more modern arms, such<br />

as “Witon” rifles. <strong>The</strong> same thing can be said for the artillery: one<br />

battery equipped with rifled steel guns, the remainder used muzzleloading<br />

bronze guns, some dating back to the 18th century. Some <strong>of</strong><br />

those guns had arrived in Paraguay as ships’ ballast. <strong>The</strong> Paraguayans<br />

also had a battery <strong>of</strong> Congréve rockets. Later in the war the Guaraníes<br />

made much use <strong>of</strong> captured equipment, especially artillery. <strong>The</strong>y were<br />

also able to build some guns at their iron works. Of note was the massive<br />

12 ton gun nicknamed El Cristiano (“<strong>The</strong> Christian”), because it<br />

was cast with the bronze bells <strong>of</strong> the churches <strong>of</strong> Asunción.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Brazilians<br />

<strong>The</strong> Brazilian army was small at the beginning <strong>of</strong> the war. Out <strong>of</strong><br />

a population <strong>of</strong> 8 million people in November 1864, they mustered<br />

only 18,000 men (in 14 infantry battalions, five cavalry regiments and<br />

five artillery regiments) <strong>The</strong> Brazilian army expanded during the war<br />

thanks to the Voluntarios de la Patria (Volunteers <strong>of</strong> the Fatherland),<br />

with 56 battalions being raised. <strong>The</strong>re were also the Guardia Nacional<br />

battalions (citizen militias <strong>of</strong> little military value). However, the<br />

Brazilians deployed a powerful navy (17 warships plus auxiliaries),<br />

which grow to 94 ships <strong>of</strong> all types with 237 guns in 1870.<br />

Aside from the navy, the other strong point <strong>of</strong> the Brazilian military<br />

was its pr<strong>of</strong>essional <strong>of</strong>ficer class. Its <strong>of</strong>ficers were among the<br />

best trained in South America, with many <strong>of</strong> them having studied<br />

at European military academies. That gave the Brazilians an edge<br />

over most Paraguayan commanders, who were largely untrained<br />

and inexperienced, and also too afraid <strong>of</strong> López to show initiative.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Brazilian ironclad Bahía passes the fortress <strong>of</strong> Humaita.<br />

Unlike their Paraguayan enemies, the Brazilian rank-and-file were recruited<br />

from among the lowest elements <strong>of</strong> society. People with enough<br />

money could avoid service by paying a substitute. That made the war less<br />

popular among the Brazilian populace, making it the same old story <strong>of</strong> “rich<br />

man’s fight, poor man’s war.” Given the lack <strong>of</strong> troops, the Brazilian government<br />

<strong>of</strong>fered the slave population the opportunity to serve in the army in<br />

exchange for emancipation. In fact, some <strong>of</strong> the best Brazilian units, such as<br />

the Bahiano Zouaves, were recruited among former slaves. <strong>The</strong>re were also<br />

many foreigners serving in the army. For instance, the 14 th Battalion was<br />

recruited exclusively from German veterans out <strong>of</strong> Schleswig-Holstein.<br />

In general, the Brazilians had more modern weaponry than the Paraguayans.<br />

That allowed them to substitute firepower for what they lacked in<br />

élan and morale. <strong>The</strong> line infantry (fusileiros) used Minié rifles, American<br />

Springfields among others. <strong>The</strong> light infantry (caçadores) used carbine versions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Minié type rifle. In 1868 at least one battalion tried the Dreysse<br />

“needle gun”, an early bolt-action rifle. <strong>The</strong> artillery deployed state-<strong>of</strong>-theart<br />

weapons such as La Hitte and Paixhams rifled guns, plus muzzle-loading<br />

Withworths <strong>of</strong> 90 to 130 mm calibers.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Argentines<br />

At the beginning <strong>of</strong> the war the Argentine Regular Army deployed<br />

some 30,000 men. Most <strong>of</strong> the units were scattered on the<br />

Indian frontier in the Pampas, while also keeping an eye on possible<br />

rebellions in the provinces. It was the city and province <strong>of</strong> Buenos<br />

Aires, (which contained about half <strong>of</strong> the 1,200,000 populace <strong>of</strong><br />

the Argentine Confederacy in 1865) which carried the main war effort.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Argentine regulars mustered seven line infantry, nine cavalry regiments<br />

and two artillery regiments at the beginning <strong>of</strong> the war. In 1864-1865,<br />

eight additional line battalions were formed for the war against Paraguay.<br />

Like the Brazilians, the Argentines deployed many troops <strong>of</strong> European<br />

origin (Germans, Italians, Polish, Swiss, etc.). When<br />

the war moved to Paraguayan territory it became less<br />

popular in the provinces, who regarded it as a Buenos<br />

Aires “private war,” so the Argentine government was<br />

forced to recruit more Europeans. After 1866 some <strong>of</strong><br />

the Argentine forces were withdrawn to face assorted<br />

rebellions in the provinces. Its organization and weaponry<br />

did not differ much from the Brazilians.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Uruguayans<br />

Uruguay was just emerging from a civil war, so<br />

it sent only a token force to contribute to the Allied<br />

war effort, initially four infantry battalions, one cavalry<br />

squadron and eight guns. <strong>The</strong> Uruguayan force<br />

received virtually no replacements during the entire<br />

campaign, being forced to recruit Paraguayan prisoners<br />

to cover losses. By 1868 the Uruguayan contingent<br />

had been reduced to some 800 troops.<br />

strategy & tactics 13

14 #245<br />

the capital. In March, a Paraguayan “commando” force<br />

<strong>of</strong> some 240 men on canoes tried to board and capture<br />

one monitor and one armoured frigate. <strong>The</strong>y managed<br />

to take control <strong>of</strong> the deck <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> those ships before<br />

being riddled with grapeshot at point blank range.<br />

With Humaitá surrounded from all sides, it was<br />

only a matter <strong>of</strong> time before the fortress would fall.<br />

An Allied probe on 16 July was bloodily repulsed despite<br />

the garrison’s growing weakness. <strong>The</strong> Allies lost<br />

some 1,500 men, the Paraguayans less than 150. On<br />

26 July the Paraguayans abandoned Humaitá. Despite<br />

the Allied naval superiority, they managed to evacuate<br />

most <strong>of</strong> the garrison by crossing on canoes and<br />

then re-crossing farther north. <strong>The</strong> remnants <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Paraguayan army were redeployed to the line <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Tebicuarí. Farther north, the Paraguayans started work<br />

on their “last stand” position, the Pikysyry Line. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

were making their final mobilization, sending children<br />

and old men to the front.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Humaitá campaign had lasted more than two<br />

years and cost both sides thousands <strong>of</strong> casualties. Now<br />

an Allied victory seemed close. To the Allies’ dismay,<br />

however, the Paraguayans were not yet ready to surrender.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ruins <strong>of</strong> the fortress <strong>of</strong> Humaitá.<br />

Dezembrada<br />

<strong>The</strong> Allies reached the Tebicuarí line on 28 August,<br />

only to discover the Paraguayans had already evacuated<br />

it and retreated farther north, to the Angostura<br />

position. Realizing a frontal assault on the Paraguayan<br />

positions would be a bloody affair, Marshall Caxias<br />

decided to bypass by building a road on the Chaco<br />

bank <strong>of</strong> the river. To the surprise <strong>of</strong> everyone (López<br />

and Caxias included), the road was finished by early<br />

December. <strong>The</strong> Allies crossed to Chaco and again recrossed<br />

the river into the enemy rear.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Paraguayans, ordered by López to defend an<br />

untenable position, were soundly defeated by the Allies<br />

in a series <strong>of</strong> summer battles called by the Brazilians<br />

the Dezembrada. At the Battles <strong>of</strong> Ytororo (6<br />

December), Arroyo Avay (11 December) and Lomas<br />

Valentinas (21-27 December), the remnants <strong>of</strong> the Paraguayan<br />

Army (“spectral battalions” as one witness<br />

put it), manned by emaciated children, convalescents<br />

and old men, were destroyed. <strong>The</strong> last <strong>of</strong> the December<br />

battles was 9,000 Allied casualties against 18,000<br />

Paraguayan.<br />

<strong>The</strong> road to Paraguay’s capital lay open, and final<br />

victory seemed within grasp <strong>of</strong> the Allied armies. Once<br />

more, though, the Allies were to be disappointed.

Endgame: the <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>of</strong> Asunción and the López<br />

Manhunt<br />

<strong>The</strong> fall <strong>of</strong> Asunción in January 1869 did not put<br />

an end the war. López refused to surrender and instead<br />

continued the struggle. At the end <strong>of</strong> January 1869 he<br />

gathered some 13,000 convalescents, escaped prisoners<br />

and stragglers at Cerro León in the highlands. López<br />

set up his new capital at Pirebebuy, 37 miles North<br />

<strong>of</strong> Asunción. <strong>The</strong> Brazilians attacked there in August<br />

and destroyed the last organized Paraguayan units.<br />

<strong>The</strong> war then degenerated into a manhunt for López.<br />

Finally, on 1 March 1870 a force <strong>of</strong> 8,000 Brazilians<br />

surrounded López and 200 <strong>of</strong> his last followers.<br />

López refused to surrender and instead charged<br />

against his pursuers, being badly wounded by a lance<br />

thrust. Prompted again to surrender, he refused and<br />

said, “Muero con mi Patria” (“I die with my fatherland”).<br />

<strong>The</strong>n a Brazilian trooper gave him the coup de<br />

grace. In that same action López’s son, a 16-year boy<br />

already a full colonel in the Paraguayan Army, was<br />

also killed.<br />

With the war ended the final tally could be made.<br />

Paraguay’s population had been reduced to some<br />

221,000 people. Total war, indeed.<br />

Artillery in the field—Uraguay, 1866.<br />

strategy & tactics 15

<strong>The</strong> Battle <strong>of</strong> Curupaity, 22 September 1866<br />

Orders <strong>of</strong> Battle<br />

Triple Alliance Army<br />

(Commander-in-Chief: Bartolomé Mitre)<br />

II Corps <strong>of</strong> the Brazilian Imperial Army<br />

(Gen. Antonio Paranhos -Viscount <strong>of</strong> Porto Alegre – 9,000/10,000 men)<br />

16 #245<br />

Caldas Division<br />

2 nd Infantry Brigade 5 th Volunteer Battalion<br />

8 th Volunteer Battalion<br />

12 th Volunteer Battalion<br />

11th Line Battalion<br />

3rd Infantry Brigade 18th Volunteer Battalion<br />

32nd Volunteer Battalion<br />

36th Volunteer Battalion<br />

7th Cavalry Brigade 7th National Guard Provisional Corps<br />

8th National Guard Provisional Corps<br />

9th National Guard Provisional Corps<br />

Albino de Carvalho Division<br />

Auxiliary Brigade 6th Battalion<br />

10th Volunteer Battalion<br />

11th Volunteer Battalion<br />

20th Volunteer Battalion<br />

46th Volunteer Battalion<br />

1st Infantry Brigade 29th Volunteer Battalion<br />

34th Volunteer Battalion<br />

47th Volunteer Battalion<br />

4th Brigade 1st Chaussers Battalion<br />

2nd Chaussers Battalion<br />

5th Chaussers Battalion<br />

De Lima Division (Reserve)<br />

6th Brigade 4th Cavalry Provisional Corps <strong>of</strong> the National Guard<br />

5th Cavalry Provisional Corps <strong>of</strong> the National Guard<br />

10th Cavalry Provisional Corps <strong>of</strong> the National Guard<br />

Light Brigade 13th Cavalry Provisional Corps <strong>of</strong> the National Guard<br />

14th Cavalry Provisional Corps <strong>of</strong> the National Guard<br />

15th Cavalry Provisional Corps <strong>of</strong> the National Guard<br />

8th Brigade 11th Cavalry Provisional Corps <strong>of</strong> the National Guard<br />

12th Cavalry Provisional Corps <strong>of</strong> the National Guard<br />

II Corps <strong>of</strong> the Argentine Army<br />

(Gen. Emílio Mitre)<br />

1 st Infantry Brigade<br />

2 nd Infantry Brigade<br />

3 rd Infantry Brigade<br />

4 th Infantry Brigade<br />

5 th Infantry Brigade<br />

6 th Infantry Brigade<br />

7 th Infantry Brigade<br />

8 th Infantry Brigade<br />

1 st Infantry Division<br />

Two Infantry Battalions<br />

Two Infantry battalions<br />

2nd Infantry Division<br />

Two Infantry Battalions<br />

Two Infantry Battalions<br />

3rd Infantry Division<br />

Two Infantry Battalions (Battalions Cordoba and San Juan)<br />

Two Infantry Battalions (Battalions Mendoza and 2nd Entrerríos)<br />

4ª Infantry Division (Col. Mateo Martinez)<br />

9th and 12th line battalions, 3rd Entre Rios battalion)<br />

1st , 2nd line battalions, 3rd National Guard Bon.<br />

Paraguayan Forces at Curupaity<br />

(Gen. José Diaz – 5,000 men)<br />

Infantry<br />

(Lt. Col. Luis Gonzales)<br />

4 th Battalion<br />

36 th Battalion<br />

38 th Battalion<br />

27 th Battalion<br />

9 th Battalion<br />

7 th Battalion<br />

40 th “Asunción” Battalion<br />

Cavalry reserve<br />

(Capt. Bernardino Caballero)<br />

6th Regiment<br />

8 th Regiment<br />

9 th Regiment<br />

36 th Regiment<br />

Artillery<br />

Some 50 guns <strong>of</strong> assorted calibers, 13 <strong>of</strong> them<br />

the advanced trench, the remainder in the main<br />

position.

Aftermath<br />

Paraguay<br />

Paraguay lost 60,000 square miles <strong>of</strong> territory to the<br />

Allies: 24,000 to Brazil and 36,000 to Argentina. <strong>The</strong> territory<br />

lost to Brazil was basically wilderness in the Matto<br />

Grosso and the upper course <strong>of</strong> the Parana, while the territory<br />

lost to Argentina included some Guarani-speaking areas<br />

as well as part <strong>of</strong> the Chaco. Still, after the Triple Alliance<br />

War the Paraguayan heartland remained untouched. <strong>The</strong><br />

other remaining Paraguayan border, that <strong>of</strong> Bolivia, remain<br />

undefined until the Chaco War <strong>of</strong> 1932-35. That time the<br />

Paraguayans won, bringing their borders to the gates <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Bolivian highlands.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Paraguayans lost around 70% <strong>of</strong> their male population,<br />

with overall losses <strong>of</strong> 120-160,000, if we include civilians<br />

and women who fought during the latter stages <strong>of</strong><br />

the war. <strong>The</strong> demographic losses were so severe, during the<br />

following decades poligamy became a common practice<br />

among the Guaranies.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Republic <strong>of</strong> Paraguay had to pay a huge war reparation<br />

to the Allies, and had to renounce sovereignty over their<br />

navigable rivers (Paraguay and Parana). <strong>The</strong>ir iron works<br />

and military industries were destroyed, the army disbanded,<br />

and fortifications dismantled. Finally, the Paraguyanas had<br />

to endure long years <strong>of</strong> Brazilian military occupation. <strong>The</strong><br />

fanatic Guarani resistence during the war had shown the<br />

Allied powers annexation <strong>of</strong> the entire country would have<br />

meant years, if not decades, <strong>of</strong> guerrilla warfare.<br />

During the postwar period Paraguay entered a spiral <strong>of</strong><br />

political instability not very different from that <strong>of</strong> their South<br />

American neighbors, with more than 40 presidents over an<br />

80 year period (1870-1954). <strong>The</strong> economy ceased to be selfsufficient<br />

and became oriented toward exporting raw materials<br />

to foreign markets. In sum, Paraguay ceased to be the<br />

exception in the South American continent, and became just<br />

one more republic complete with political inestability, foreign<br />

debt and an economy that produced raw materials for<br />

European industry.<br />

I Corps <strong>of</strong> the Argentine Army<br />

(Gen. Wenceslao Paunero)<br />

1 st Infantry Brigade<br />

2 nd Infantry Brigade<br />

3rd Infantry Brigade<br />

4 th Infantry Brigade<br />

5 th Infantry Brigade<br />

6 th Infantry Brigade<br />

7 th Infantry Brigade<br />

8 th Infantry Brigade<br />

<strong>The</strong> Brazilian Empire<br />

In order to win the war, the Brazilian Empire had to create<br />

a standing army that, within less than 20 years, would destroy<br />

the delicate balance <strong>of</strong> power in its own society. <strong>The</strong> intervention<br />

<strong>of</strong> the army in Brazilian politics would ultimately lead<br />

to the fall <strong>of</strong> the emperor and the proclamation <strong>of</strong> a republic.<br />

Argentina<br />

<strong>The</strong> war was the catalyst that helped Argentina forge a<br />

nation out <strong>of</strong> a conglomerate <strong>of</strong> provinces. Of all the Allied<br />

leaders, Argentina’s Mitre was the only one who had a clear objective<br />

for the war, and he achieved it: to unify Argentina under<br />

the political and economical leadership <strong>of</strong> Buenos Aires.<br />

1 st Infantry Division<br />

Period photo <strong>of</strong> militia—Triple Alliance War.<br />

Two Infantry Battalions<br />

One Infantry Battalion and the Military Legion<br />

2nd Infantry Division<br />

Two Infantry Battalions<br />

One Infantry Battalion and the 1st Volunteer Legion<br />

3rd Infantry Division<br />

Two Infantry Battalions<br />

Two Infantry Battalions<br />

4th Infantry Division<br />

Two Infantry Battalions<br />

One Battalion and one the 2nd Volunteer Legion<br />

strategy & tactics 17

18 #245<br />

THE COST<br />

Losses:<br />

Allies: Some 100,000 deaths (civilians included).<br />

Paraguay: 120,000 to 160,000 deaths (civilians included).<br />

Main Battles <strong>of</strong> the TAW<br />

Name Date Result Paraguayan force Paraguayan<br />

losses<br />