Download (PDF, 6.71MB) - TEEB

Download (PDF, 6.71MB) - TEEB Download (PDF, 6.71MB) - TEEB

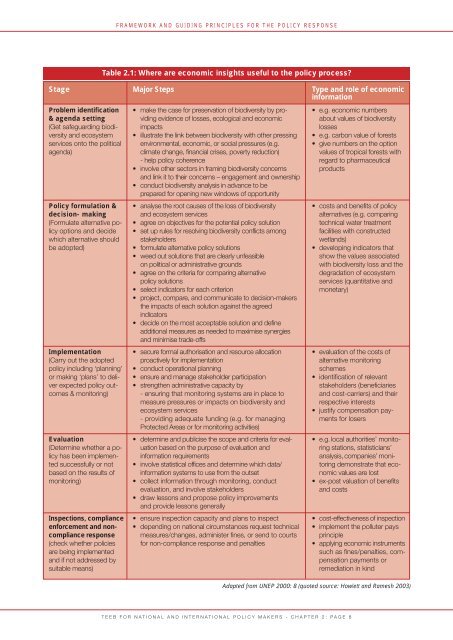

Stage Problem identification & agenda setting (Get safeguarding biodiversity and ecosystem services onto the political agenda) Policy formulation & decision- making (formulate alternative policy options and decide which alternative should be adopted) Implementation (Carry out the adopted policy including ‘planning’ or making ‘plans’ to deliver expected policy outcomes & monitoring) Evaluation (Determine whether a policy has been implemented successfully or not based on the results of monitoring) Inspections, compliance enforcement and noncompliance response (check whether policies are being implemented and if not addressed by suitable means) FRAMEWORK AND GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR THE POLICY RESPONSE Table 2.1: Where are economic insights useful to the policy process? Major Steps • make the case for preservation of biodiversity by providing evidence of losses, ecological and economic impacts • illustrate the link between biodiversity with other pressing environmental, economic, or social pressures (e.g. climate change, financial crises, poverty reduction) - help policy coherence • involve other sectors in framing biodiversity concerns and link it to their concerns – engagement and ownership • conduct biodiversity analysis in advance to be prepared for opening new windows of opportunity • analyse the root causes of the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services • agree on objectives for the potential policy solution • set up rules for resolving biodiversity conflicts among stakeholders • formulate alternative policy solutions • weed out solutions that are clearly unfeasible on political or administrative grounds • agree on the criteria for comparing alternative policy solutions • select indicators for each criterion • project, compare, and communicate to decision-makers the impacts of each solution against the agreed indicators • decide on the most acceptable solution and define additional measures as needed to maximise synergies and minimise trade-offs • secure formal authorisation and resource allocation proactively for implementation • conduct operational planning • ensure and manage stakeholder participation • strengthen administrative capacity by - ensuring that monitoring systems are in place to measure pressures or impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services - providing adequate funding (e.g. for managing Protected Areas or for monitoring activities) • determine and publicise the scope and criteria for evaluation based on the purpose of evaluation and information requirements • involve statistical offices and determine which data/ information systems to use from the outset • collect information through monitoring, conduct evaluation, and involve stakeholders • draw lessons and propose policy improvements and provide lessons generally • ensure inspection capacity and plans to inspect • depending on national circumstances request technical measures/changes, administer fines, or send to courts for non-compliance response and penalties TEEB foR NATIoNAL AND INTERNATIoNAL PoLICy MAKERS - ChAPTER 2: PAGE 8 Type and role of economic information • e.g. economic numbers about values of biodiversity losses • e.g. carbon value of forests • give numbers on the option values of tropical forests with regard to pharmaceutical products • costs and benefits of policy alternatives (e.g. comparing technical water treatment facilities with constructed wetlands) • developing indicators that show the values associated with biodiversity loss and the degradation of ecosystem services (quantitative and monetary) • evaluation of the costs of alternative monitoring schemes • identification of relevant stakeholders (beneficiaries and cost-carriers) and their respective interests • justify compensation payments for losers • e.g. local authorities’ monitoring stations, statisticians’ analysis, companies’ monitoring demonstrate that economic values are lost • ex-post valuation of benefits and costs • cost-effectiveness of inspection • implement the polluter pays principle • applying economic instruments such as fines/penalties, compensation payments or remediation in kind Adapted from UNEP 2000: 8 (quoted source: Howlett and Ramesh 2003)

FRAMEWORK AND GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR THE POLICY RESPONSE Box 2.3 provides examples of how economic information can be applied at decision-making stage. Box 2.4 illustrates the use of economic valuation at a later stage, after damage has occurred, to guide legal remedies and the award of compensation. Box 2.3: Using valuation as part of a decision support system Indonesia: the Segah watershed (Berau District) contains some of the largest tracts of undisturbed lowland forest in East Kalimantan (150,000 hectares) which provide the last substantial orang-utan habitat. A 2002 valuation study concluded that water from the Segah river and the nearby Kelay river had an estimated value of more than US$ 5.5 million/year (e.g. regulation of water flow rates and sediment loads to protect infrastructure and irrigation systems). In response to these findings, the Segah Watershed Management Committee was established to protect the watershed. Source: The Nature Conservancy 2007 Uganda: the Greater City of Kampala benefits from services provided by the Nakivubo Swamp (catchment area > 40 km²) which cleans water polluted by industrial, urban and untreated sewage waste. A valuation study looked at the cost of replacing wetland wastewater processing services with artificial technologies (i.e. upgraded sewage treatment plant, construction of latrines to process sewage from nearby slums). It concluded that the infrastructure required to achieve a similar level of wastewater treatment to that naturally provided by the wetland would cost up to US$2 million/year c.f. the costs of managing the natural wetland to optimise its waste treatment potential and maintain its ecological integrity (about US$ 235,000). on the basis of this economic argument, plans to drain and reclaim the wetland were reversed and Nakivubo was legally designated as part of the city’s greenbelt zone. Sources: Emerton and Bos 2004; UNDP-UNEP Poverty-Environment Facility 2008 Box 2.4: Economic valuation of damages to enforce liability rules The accident of the Exxon valdez tanker in 1989 triggered the application of Contingent valuation Methods for studies conducted in order to establish the magnitude of liability for the injuries occurred to the natural resources, under the Comprehensive, Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA). A panel headed by Nobel laureates K. Arrow and R. Solow appointed to advice NoAA on the appropriateness of use of CvM in nature resource damage assessments. In their report the panel concluded that CvM studies can produce estimates reliable enough to be the starting point of a judicial process of damage assessment including passive-use values. To apply CvM appropriately, the panel drew up a list of guidelines for contingent valuation studies. While some of the guidelines have attracted some criticism, the majority has been accepted widely. Source: Navrud and Pruckner 1996 2.2.3 BROADER USES OF ECONOMIC VALUES IN POLICY-MAKING Successful biodiversity policies are often restricted to a small number of countries, because they are unknown or poorly understood beyond these countries. Economics can highlight that there are policies that already work well, deliver more benefits than costs and are effective and efficient. The REDD scheme (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation), introduced as a key climate policy instrument in 2007, has already stimulated broader interest in payment for ecosystem services (PES) (see Chapter 5). Several countries and organisations have collated case studies on REDD design and implementation that can be useful for other countries and applications (Parker et al. 2009). other examples of approaches that could be used more widely for biodiversity objectives include e.g. green public procurement and instruments based on the polluter-pays principle (see Chapter 7). TEEB foR NATIoNAL AND INTERNATIoNAL PoLICy MAKERS - ChAPTER 2: PAGE 9

- Page 33 and 34: EfErENcEs THE GLOBAL BIODIVERSITY C

- Page 35 and 36: THE GLOBAL BIODIVERSITY CRISIS AND

- Page 37 and 38: Part I: The need for action Ch1 The

- Page 39 and 40: THE ECONOMICS OF ECOSYSTEMS AND BIO

- Page 41 and 42: 10.1 WHY VALUING ECOSYSTEM SERVICES

- Page 43 and 44: RESPONDING TO THE VALUE OF NATURE B

- Page 45 and 46: RESPONDING TO THE VALUE OF NATURE B

- Page 47 and 48: RESPONDING TO THE VALUE OF NATURE B

- Page 49 and 50: 10.2.2 BETTER LINKS TO MACRO- ECONO

- Page 51 and 52: 10.3 Investing in natural capital s

- Page 53 and 54: as well as the value for money and

- Page 55 and 56: Global National or Regional Local T

- Page 57 and 58: RESPONDING TO THE VALUE OF NATURE B

- Page 59 and 60: 10.4 By taking distributional issue

- Page 61 and 62: has origins and impacts beyond bord

- Page 63 and 64: The ‘Nobel Prize’*-winning econ

- Page 65 and 66: 10.5 Biodiversity and ecosystem ser

- Page 67 and 68: Rewarding the provision of services

- Page 69 and 70: Making this a reality will require

- Page 71 and 72: GHK, CE and IEEP - GHK, Cambridge E

- Page 73 and 74: Torras, M. (2000) The Total Economi

- Page 75 and 76: Part I: The need for action Ch1 The

- Page 77 and 78: ThE ECoNoMICS of ECoSySTEMS AND BIo

- Page 79 and 80: FRAMEWORK AND GUIDING PRINCIPLES FO

- Page 81 and 82: FRAMEWORK AND GUIDING PRINCIPLES FO

- Page 83: FRAMEWORK AND GUIDING PRINCIPLES FO

- Page 87 and 88: 2.3 FRAMEWORK AND GUIDING PRINCIPLE

- Page 89 and 90: FRAMEWORK AND GUIDING PRINCIPLES FO

- Page 91 and 92: FRAMEWORK AND GUIDING PRINCIPLES FO

- Page 93 and 94: FRAMEWORK AND GUIDING PRINCIPLES FO

- Page 95 and 96: 2.3.4 BASE POLICIES ON GOOD GOVERNA

- Page 97 and 98: 2.4 FRAMEWORK AND GUIDING PRINCIPLE

- Page 99 and 100: REfERENCES FRAMEWORK AND GUIDING PR

- Page 101 and 102: Part I: The need for action Ch1 The

- Page 103 and 104: THE ECONOMICS OF ECOSYSTEMS AND BIO

- Page 105 and 106: STRENGTHENING INDICATORS AND ACCOUN

- Page 107 and 108: 3.1 STRENGTHENING INDICATORS AND AC

- Page 109 and 110: STRENGTHENING INDICATORS AND ACCOUN

- Page 111 and 112: STRENGTHENING INDICATORS AND ACCOUN

- Page 113 and 114: STRENGTHENING INDICATORS AND ACCOUN

- Page 115 and 116: STRENGTHENING INDICATORS AND ACCOUN

- Page 117 and 118: STRENGTHENING INDICATORS AND ACCOUN

- Page 119 and 120: STRENGTHENING INDICATORS AND ACCOUN

- Page 121 and 122: STRENGTHENING INDICATORS AND ACCOUN

- Page 123 and 124: STRENGTHENING INDICATORS AND ACCOUN

- Page 125 and 126: 3.3 STRENGTHENING INDICATORS AND AC

- Page 127 and 128: STRENGTHENING INDICATORS AND ACCOUN

- Page 129 and 130: 3.4 STRENGTHENING INDICATORS AND AC

- Page 131 and 132: STRENGTHENING INDICATORS AND ACCOUN

- Page 133 and 134: STRENGTHENING INDICATORS AND ACCOUN

Stage<br />

Problem identification<br />

& agenda setting<br />

(Get safeguarding biodiversity<br />

and ecosystem<br />

services onto the political<br />

agenda)<br />

Policy formulation &<br />

decision- making<br />

(formulate alternative policy<br />

options and decide<br />

which alternative should<br />

be adopted)<br />

Implementation<br />

(Carry out the adopted<br />

policy including ‘planning’<br />

or making ‘plans’ to deliver<br />

expected policy outcomes<br />

& monitoring)<br />

Evaluation<br />

(Determine whether a policy<br />

has been implemented<br />

successfully or not<br />

based on the results of<br />

monitoring)<br />

Inspections, compliance<br />

enforcement and noncompliance<br />

response<br />

(check whether policies<br />

are being implemented<br />

and if not addressed by<br />

suitable means)<br />

FRAMEWORK AND GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR THE POLICY RESPONSE<br />

Table 2.1: Where are economic insights useful to the policy process?<br />

Major Steps<br />

• make the case for preservation of biodiversity by providing<br />

evidence of losses, ecological and economic<br />

impacts<br />

• illustrate the link between biodiversity with other pressing<br />

environmental, economic, or social pressures (e.g.<br />

climate change, financial crises, poverty reduction)<br />

- help policy coherence<br />

• involve other sectors in framing biodiversity concerns<br />

and link it to their concerns – engagement and ownership<br />

• conduct biodiversity analysis in advance to be<br />

prepared for opening new windows of opportunity<br />

• analyse the root causes of the loss of biodiversity<br />

and ecosystem services<br />

• agree on objectives for the potential policy solution<br />

• set up rules for resolving biodiversity conflicts among<br />

stakeholders<br />

• formulate alternative policy solutions<br />

• weed out solutions that are clearly unfeasible<br />

on political or administrative grounds<br />

• agree on the criteria for comparing alternative<br />

policy solutions<br />

• select indicators for each criterion<br />

• project, compare, and communicate to decision-makers<br />

the impacts of each solution against the agreed<br />

indicators<br />

• decide on the most acceptable solution and define<br />

additional measures as needed to maximise synergies<br />

and minimise trade-offs<br />

• secure formal authorisation and resource allocation<br />

proactively for implementation<br />

• conduct operational planning<br />

• ensure and manage stakeholder participation<br />

• strengthen administrative capacity by<br />

- ensuring that monitoring systems are in place to<br />

measure pressures or impacts on biodiversity and<br />

ecosystem services<br />

- providing adequate funding (e.g. for managing<br />

Protected Areas or for monitoring activities)<br />

• determine and publicise the scope and criteria for evaluation<br />

based on the purpose of evaluation and<br />

information requirements<br />

• involve statistical offices and determine which data/<br />

information systems to use from the outset<br />

• collect information through monitoring, conduct<br />

evaluation, and involve stakeholders<br />

• draw lessons and propose policy improvements<br />

and provide lessons generally<br />

• ensure inspection capacity and plans to inspect<br />

• depending on national circumstances request technical<br />

measures/changes, administer fines, or send to courts<br />

for non-compliance response and penalties<br />

<strong>TEEB</strong> foR NATIoNAL AND INTERNATIoNAL PoLICy MAKERS - ChAPTER 2: PAGE 8<br />

Type and role of economic<br />

information<br />

• e.g. economic numbers<br />

about values of biodiversity<br />

losses<br />

• e.g. carbon value of forests<br />

• give numbers on the option<br />

values of tropical forests with<br />

regard to pharmaceutical<br />

products<br />

• costs and benefits of policy<br />

alternatives (e.g. comparing<br />

technical water treatment<br />

facilities with constructed<br />

wetlands)<br />

• developing indicators that<br />

show the values associated<br />

with biodiversity loss and the<br />

degradation of ecosystem<br />

services (quantitative and<br />

monetary)<br />

• evaluation of the costs of<br />

alternative monitoring<br />

schemes<br />

• identification of relevant<br />

stakeholders (beneficiaries<br />

and cost-carriers) and their<br />

respective interests<br />

• justify compensation payments<br />

for losers<br />

• e.g. local authorities’ monitoring<br />

stations, statisticians’<br />

analysis, companies’ monitoring<br />

demonstrate that economic<br />

values are lost<br />

• ex-post valuation of benefits<br />

and costs<br />

• cost-effectiveness of inspection<br />

• implement the polluter pays<br />

principle<br />

• applying economic instruments<br />

such as fines/penalties, compensation<br />

payments or<br />

remediation in kind<br />

Adapted from UNEP 2000: 8 (quoted source: Howlett and Ramesh 2003)