Reclaiming Our Rural Highways - the Dorset AONB

Reclaiming Our Rural Highways - the Dorset AONB

Reclaiming Our Rural Highways - the Dorset AONB

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

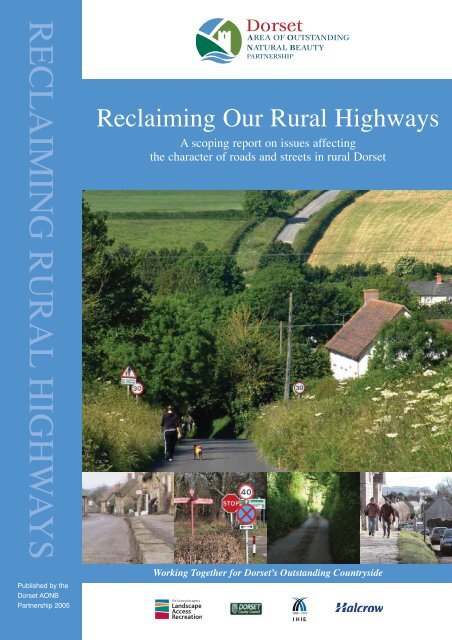

RECLAIMING RURAL HIGHWAYS<br />

Published by <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Dorset</strong> <strong>AONB</strong><br />

Partnership 2005<br />

<strong>Reclaiming</strong> <strong>Our</strong> <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Highways</strong><br />

A scoping report on issues affecting<br />

<strong>the</strong> character of roads and streets in rural <strong>Dorset</strong><br />

Working Toge<strong>the</strong>r for <strong>Dorset</strong>’s Outstanding Countryside

Acknowledgements<br />

Author: James Purkiss, Halcrow<br />

With particular assistance from: Sarah Bentley, <strong>Dorset</strong><br />

<strong>AONB</strong> Partnership, and Stephen Hardy, <strong>Dorset</strong> County<br />

Council<br />

With contributions from: Countryside Agency (Alison<br />

Rood), <strong>Dorset</strong> <strong>AONB</strong> Partnership (Doug Harman), <strong>Dorset</strong><br />

County Council (Sarah Barber, David Dawkins, Andy<br />

Elliott, John Lowe, Phil Sterling, Andy Tate & Rod Webb)<br />

English Nature (Jim White), Kate Freeman, Friends of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Lake District (Jack Ellerby) Halcrow Group<br />

(Steve Morgan, Andrew Linfoot, Clare Simmons)<br />

Gloucestershire County Council (Alexandra Luck), Kent<br />

County Council (Richard Emmett), Quantocks <strong>AONB</strong><br />

Service, Slower Speeds Initiative, Suffolk County Council<br />

(Ruth Stokes), Sustrans (Jonathan Bewley), West<br />

Berkshire Council (Jenny Noble)<br />

Thanks to all <strong>the</strong> organisations, committees and<br />

individuals who have contributed to <strong>the</strong> development<br />

of this Plan.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Photographs used by kind permission of:<br />

• Common Ground<br />

• <strong>Dorset</strong> <strong>AONB</strong> Partnership<br />

• <strong>Dorset</strong> County Council (Stephen Hardy, Mark Simons)<br />

• <strong>Dorset</strong> Engineering Consultancy (Julian McLaughlin)<br />

• Friends of <strong>the</strong> Lake District<br />

• Halcrow Group (James Purkiss)<br />

• Images of <strong>Dorset</strong> (John Allen)<br />

• Kent County Council (Richard Emmett)<br />

• The National Trust<br />

• North <strong>Dorset</strong> District Council<br />

• Quantock Hills <strong>AONB</strong> Service<br />

• Suffolk County Council (Ruth Stokes)<br />

• Sustrans (John Grimshaw, Steve Morgan)<br />

• Transport 2000 (Graham Smith)<br />

Designed and produced by Origin Designs Ltd.<br />

Maps are based upon Ordnance Survey material with <strong>the</strong><br />

permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of <strong>the</strong><br />

Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office. (C) Crown<br />

Copyright 2001. Unauthorised reproduction infringes<br />

Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil<br />

proceedings. (C) <strong>Dorset</strong> County Council. LA 076570.<br />

2001.Office. (C) Crown Copyright 2002.<br />

Acknowledgements

Contents<br />

4 4<br />

Contents<br />

Page<br />

Foreword 4<br />

Executive Summary 6<br />

1.1 Setting <strong>the</strong> scene 6<br />

1.2 The first step 6<br />

1.3 New approaches to rural roads 7<br />

1.4 Future Steps 7<br />

Section I: Overview of issues and problems 8<br />

2.1 Rationale for <strong>the</strong> study 9<br />

2.2 Aim of study 11<br />

2.3 The importance of <strong>Dorset</strong>’s environment 11<br />

2.4 The importance of <strong>Dorset</strong>’s rural roads 13<br />

2.5 The importance of design 15<br />

2.6 Insensitive design of rural roads 15<br />

2.7 Policy Context 17<br />

Section II: Evaluation of rural road management methods 21<br />

3 De-cluttering and quality design 22<br />

3.1 Introduction to chapter 22<br />

3.2 Clutter removal 24<br />

3.3 Amalgamation and multi-functionality 24<br />

3.4 Improved design 24<br />

3.5 Improved street and road boundary material design 25<br />

3.6 Improved signage design 26<br />

3.7 Improved design of o<strong>the</strong>r street features 30<br />

4 Protecting <strong>the</strong> natural and built environment 32<br />

4.1 Introduction 32<br />

4.2 Conserving ecology 32<br />

4.3 Wildlife 34<br />

4.4 Light and noise pollution 34<br />

4.5 Conserving archaeological and historic features 36<br />

4.6 Conserving <strong>the</strong> historic environment: signs 36<br />

4.7 Conserving <strong>the</strong> historic environment: o<strong>the</strong>r built features 37<br />

5 Managing traffic: traffic calming and traditional measures 38<br />

5.1 Traditional measures 38<br />

5.2 Traffic calming and environmental enhancement 39<br />

5.3 Dealing with ‘rat runs’ 40<br />

5.4 Dealing with inappropriate vehicle speeds 41<br />

5.5 Applying a structured speed limit regime 41<br />

5.6 Speed limit enforcement 44<br />

6 Managing traffic: innovative measures 46<br />

6.1 Can highway design be improved? 46<br />

6.2 Successful design: <strong>the</strong> <strong>Dorset</strong> perspective 48<br />

6.3 The application of psychology 48<br />

6.4 Changing attitudes 50<br />

6.5 Shared spaces 50<br />

6.6 Reassessing village roads 52<br />

6.7 Reassessing rural lanes 53<br />

6.8 Removal of white line markings 54<br />

6.9 Reassessing road junctions 55<br />

7 Route functions: which routes for which users? 56<br />

7.1 Introduction: functional use versus leisure use 56<br />

7.2 Strategic functions 57<br />

7.3 Direction signing 60<br />

8 Route functions: non-motorised users 62<br />

8.2 Rights of way: issues and problems 62

Contents<br />

Page<br />

8.3 Planning for rights of way 63<br />

8.4 Planning for non-motorised use of rural roads 64<br />

8.5 Planning for pedestrians 64<br />

8.6 Planning for cyclists 65<br />

8.7 Planning for equine traffic 66<br />

8.8 Comprehensive planning for non-motorised users: quiet lanes 67<br />

9 Policy, guidance and hierarchies 68<br />

9.1 Policy and guidance 68<br />

9.2 Local publications 68<br />

9.3 Categorisation and hierarchies 69<br />

9.4 Assessing areas or specific roads 70<br />

9.5 Summary 71<br />

10 Maintaining <strong>the</strong> roads 72<br />

Section III: <strong>Dorset</strong>’s distinctiveness 75<br />

Introduction: <strong>Dorset</strong>’s streetscape features 75<br />

11 Roadside surfaces and boundaries 76<br />

11.1 Surfaces 76<br />

11.2 Hedges 76<br />

11.3 Walls 77<br />

11.4 Fences and railings 77<br />

11.5 Gates 77<br />

11.6 Trees 77<br />

11.7 Verges 78<br />

11.8 Townscapes 78<br />

11.9 Bridge designs, materials and name plaques 80<br />

11.10 Fords 81<br />

12 Roadside features 82<br />

12.1 Raised footways 82<br />

12.2 Turnpike artefacts 82<br />

12.3 Public utility furniture 83<br />

12.4 Place name signs 84<br />

12.5 Street nameplates 84<br />

12.6 Fingerposts 84<br />

12.7 O<strong>the</strong>r roadside features 86<br />

13 Statutory protection and current information 88<br />

13.1 Overview 88<br />

13.2 Designations 88<br />

13.3 Information 90<br />

14 Characterising <strong>Dorset</strong>’s rural roads 92<br />

14.2 Blackmoor Vale 92<br />

14.3 <strong>Dorset</strong> Downs 93<br />

14.4 <strong>Dorset</strong> Heaths 93<br />

14.5 South Purbeck 94<br />

14.6 Weymouth Lowlands 94<br />

14.7 Marshwood and Powerstock Vales 94<br />

14.8 Yeovil Scarplands 95<br />

14.9 Blackdown Hills 95<br />

14.10 Classifying routes in <strong>Dorset</strong> according to individual road character 95<br />

Section IV: Summary and recommendations 97<br />

15 Conclusions 98<br />

15.2 Recommendations 100<br />

16 Glossary and Bibliography 102<br />

Glossary 102<br />

Bibliography 102<br />

Contents<br />

5

6<br />

Foreword<br />

"More sympa<strong>the</strong>tic management of rural roads will<br />

make a tremendously positive contribution to <strong>the</strong><br />

conservation and enhancement of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Dorset</strong> <strong>AONB</strong>.<br />

I hope this document will help to bring this about, and<br />

perhaps encourage and help o<strong>the</strong>r Partnerships and<br />

authorities to tackle this issue."<br />

Alan Swindall, Chairman,<br />

<strong>Dorset</strong> <strong>AONB</strong> Partnership<br />

"The IHIE has, for several years, been championing<br />

engineers and designers to push <strong>the</strong> boundaries when<br />

influencing <strong>the</strong> design of residential highways in new,<br />

high quality urban development settings.<br />

I am very pleased <strong>the</strong>refore that we are now also at<br />

<strong>the</strong> forefront of applying <strong>the</strong> same concepts to<br />

influencing <strong>the</strong> consideration of highways in high<br />

quality rural landscape settings.<br />

In particular I am pleased that <strong>the</strong> Institution has<br />

been involved in work that will lead, potentially, to<br />

<strong>the</strong> deurbanisation of highways across <strong>Dorset</strong>'s<br />

beautiful landscape"<br />

Gerry Harvey, President,<br />

Institute of Highway Incorporated Engineers 2004-2006<br />

"<strong>Rural</strong> roads contribute to local distinctiveness and<br />

require sensitive management in order to retain <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

distinctiveness. The Countryside Agency supports<br />

exemplary practice for all roads in designated<br />

landscapes, and endorses this publication as a<br />

positive step in preserving and enhancing <strong>the</strong> special<br />

features of <strong>the</strong> <strong>AONB</strong>."<br />

Alison Rood, Countryside Agency<br />

"English Nature welcomes this novel report<br />

since <strong>the</strong>re is a wealth of characteristic biodiversity<br />

along our rural road verges... <strong>the</strong>re are opportunities<br />

to enhance this with appropriate and sympa<strong>the</strong>tic<br />

management practices or new plantings, to benefit<br />

wildlife and to enrich our experience of using <strong>the</strong><br />

rural roads network".<br />

Jim White, <strong>Dorset</strong> Team Leader,<br />

English Nature<br />

"...<strong>the</strong> environment through which people travel<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r by car, bus, cycle, horseback or on foot is<br />

becoming more important as safety and traffic<br />

congestion issues begin to dictate how road design is<br />

altered to bring about changes in driving behaviour,<br />

removing traffic from villages and ensure that it can<br />

keep moving.<br />

I think anything that can be done to recognise <strong>the</strong><br />

historic importance of routes should be welcome and<br />

that any traffic hierarchy model should include in its<br />

criteria <strong>the</strong> importance of <strong>the</strong> history and use of routes."<br />

Jo Burgon, Travel Group Chairman,<br />

The National Trust<br />

"The historic environment can easily be eroded<br />

by a plethora of unnecessary signs. Careful use<br />

of signs and road markings, and retention of items of<br />

interest such as rural fingerposts, not only reinforces<br />

character but can form part of a successful traffic<br />

management approach."<br />

Jenny Frew, Senior Policy Officer, Transport,<br />

English Heritage

<strong>Dorset</strong>’s landscape is one of <strong>the</strong> most precious and<br />

varied in <strong>the</strong> country – with a wealth of statutory<br />

designations to prove it! These reflect not only <strong>the</strong><br />

tremendously rich natural environment, but also <strong>the</strong><br />

historical built environment as well. Inextricably linked to<br />

both are <strong>the</strong> man made routes across <strong>the</strong> county – some<br />

established thousands of years ago. Many of <strong>the</strong>se routes,<br />

along with <strong>the</strong> characteristic features that have developed<br />

alongside <strong>the</strong>m, have an intrinsic and historical value.<br />

Over recent years, traffic volume and speed has<br />

increased considerably, resulting in concerns over<br />

environmental impacts and safety. The way we manage<br />

our network of highway routes has huge implications for<br />

our communities, visitors and our environment. It is of<br />

course essential that we ensure <strong>the</strong> safety of all highway<br />

users. It is equally essential however that we minimise,<br />

or better still reduce, <strong>the</strong> detrimental engineered impact<br />

of highway management and use on our countryside. We<br />

need to keep <strong>Dorset</strong>’s landscape special for all to enjoy<br />

now and in <strong>the</strong> future.<br />

<strong>Our</strong> rural roads are being urbanised and degraded by an<br />

increasing quantity of signs, kerbs, road markings and<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r street furniture. We know that we can do better;<br />

indeed, in <strong>Dorset</strong> we have learnt much about<br />

incorporating highways into high quality urban design. It<br />

is time we translated <strong>the</strong>se skills in <strong>the</strong> rural setting. It is<br />

a policy objective of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Dorset</strong> <strong>AONB</strong> Management Plan<br />

to ensure that road design, signage and maintenance are<br />

sympa<strong>the</strong>tic to <strong>the</strong> character of rural roads in <strong>the</strong> <strong>AONB</strong>.<br />

Responding to this and through <strong>the</strong> <strong>Dorset</strong> <strong>AONB</strong><br />

Partnership, working jointly with <strong>Dorset</strong> County Council<br />

as Local Highway Authority, a commitment has been<br />

Foreword<br />

made to develop new approaches to highways. This<br />

study is <strong>the</strong> first step; it catalogues <strong>the</strong> issues and how,<br />

with flexibility of thinking, <strong>the</strong>y have been tackled<br />

elsewhere, providing a valuable evidence base. It also<br />

sets <strong>the</strong> <strong>Dorset</strong> scene, highlighting <strong>the</strong> special features<br />

we want to keep. But most of all, this study sets us a<br />

challenge - one that we must work hard to meet.<br />

During <strong>the</strong> extensive contact with o<strong>the</strong>r authorities,<br />

<strong>AONB</strong>s and National Park Authorities made in<br />

researching this study, we have received many requests<br />

for copies of <strong>the</strong> finished report. This is clearly an issue<br />

that resonates across many rural landscapes.<br />

Consequently, we hope that by publishing our findings so<br />

far, we may help encourage o<strong>the</strong>r protected landscape<br />

teams and local highway authorities to take up <strong>the</strong> challenge.<br />

I look forward to working with all <strong>the</strong> partners in <strong>the</strong><br />

ongoing work in <strong>Dorset</strong>. <strong>Our</strong> intended result is to bring<br />

forward design and management guidance that will<br />

inform <strong>the</strong> implementation of transport network<br />

improvements and development with designs that are<br />

appropriate to <strong>Dorset</strong>’s local context and reinforce local<br />

distinctiveness throughout <strong>the</strong> county.<br />

Councillor Hilary Cox<br />

Environment Portfolio Holder,<br />

<strong>Dorset</strong> County Council<br />

<strong>Dorset</strong> <strong>AONB</strong> Partnership<br />

Board Member<br />

7

Chapter 1: Executive Summary<br />

8 8<br />

1.1 Setting <strong>the</strong> scene<br />

Chapter 1: Executive Summary<br />

1.1.1 <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Dorset</strong> has a high quality built, cultural and<br />

natural heritage envied by many, with a great<br />

diversity of landscapes. The county’s combination<br />

of countryside, villages, small towns and coastline<br />

contributes to a high quality of life for residents<br />

and visitors.<br />

1.1.2 Roads are an intrinsic part of <strong>the</strong> landscape which<br />

surrounds us. Most roads and lanes are much<br />

older than <strong>the</strong> buildings which line <strong>the</strong>m and<br />

evidence of Roman and older routes remain in <strong>the</strong><br />

county today. Which came first – <strong>the</strong> river crossing<br />

at which a village grew up, or <strong>the</strong> route to connect<br />

<strong>the</strong> existing villages?<br />

1.1.3 The county’s highly prized environment is not<br />

without significant threats to its well-being and <strong>the</strong><br />

rural roads that lace it are no exception to this.<br />

Traffic volumes continue to rise across this<br />

network, and as congestion worsens on <strong>the</strong> major<br />

roads, traffic is finding alternative, less suitable<br />

routes. The rising public awareness of new tourist<br />

destinations is resulting in new travel patterns and<br />

larger numbers of visitors to <strong>the</strong> county. This is<br />

compounded by <strong>the</strong> county’s fast population<br />

growth expanding into a largely unimproved<br />

road network.<br />

<strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Dorset</strong> is famed for <strong>the</strong> quality of its environment<br />

1.1.4 Traditional responses to <strong>the</strong> pressures of<br />

increasing traffic volumes on narrow, unimproved<br />

roads were to widen and straighten <strong>the</strong>m. These<br />

traditional ‘improvement’ approaches have led to<br />

<strong>the</strong> proliferation of signs and road markings<br />

which are not always sympa<strong>the</strong>tic to <strong>the</strong> rural<br />

environment. They have also led to <strong>the</strong> character,<br />

ecology and archaeology of rural areas being<br />

damaged. Such engineered improvements can<br />

lead to increased vehicle speeds and can deter<br />

travel by horseriders, walkers and cyclists. It is<br />

unlikely that <strong>the</strong>se outcomes were intentional<br />

but instead reflect <strong>the</strong> current incremental,<br />

engineered, crisis-response approach to rural<br />

road management.<br />

1.2 The first step<br />

1.2.1 The <strong>Dorset</strong> <strong>AONB</strong> (D<strong>AONB</strong>) Management Plan<br />

identified many of <strong>the</strong> above issues as being in<br />

conflict with <strong>the</strong> statutory duty to conserve and<br />

enhance <strong>the</strong> <strong>AONB</strong>. This led to <strong>the</strong> inclusion in <strong>the</strong><br />

Plan of an objective (policy TR4) to:<br />

‘Ensure that road design, delivery, signage<br />

and maintenance are sympa<strong>the</strong>tic to <strong>the</strong><br />

special character of rural roads and<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>AONB</strong>’

1.2.2 This document, <strong>Reclaiming</strong> our <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Highways</strong>,<br />

is <strong>the</strong> first step towards ensuring that <strong>the</strong> special<br />

character of rural roads is understood and taken<br />

account of in design and management decisions.<br />

It draws toge<strong>the</strong>r information on rural road<br />

management from a wide variety of sources and<br />

outlines each of <strong>the</strong> pertinent issues using case<br />

studies from <strong>Dorset</strong> and elsewhere to identify<br />

solutions. The topics covered are often equally<br />

applicable to o<strong>the</strong>r parts of rural England, and indeed,<br />

in essence to Scotland, Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland and Wales.<br />

1.2.3 <strong>Reclaiming</strong> our <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Highways</strong> is aimed at all<br />

those with an interest in rural roads and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

management. It acts as a significant<br />

contemporary reference for <strong>the</strong> wide range of<br />

interests and professions that are involved with<br />

<strong>the</strong> functions, management and work of rural areas.<br />

In practice, it is intended to inform future design<br />

and conservation-led decision-making by Local<br />

Planning Authorities and Local Highway Authorities.<br />

1.3 New approaches to rural roads<br />

1.3.1 Whilst <strong>the</strong> issue of looking after rural roads is a<br />

complex one, <strong>the</strong>re are many examples which<br />

illustrate that innovative and sympa<strong>the</strong>tic<br />

approaches to problem solving are possible. Of<br />

particular interest are approaches which:<br />

• create shared spaces, where <strong>the</strong> traditional<br />

distinction between space for pedestrians and<br />

space for vehicles is minimised or abolished;<br />

• use inherently rural features such as hedges,<br />

banks, walls, <strong>the</strong> position of buildings and bridges<br />

as features to naturally calm traffic;<br />

• ensure that clutter is kept to <strong>the</strong> minimum<br />

necessary for <strong>the</strong> safe operation of <strong>the</strong> road network;<br />

• ensure that whatever works are carried out conserve<br />

and enhance <strong>the</strong> local distinctiveness of <strong>the</strong> county.<br />

1.3.2 <strong>Dorset</strong> is recognised as a county in which leading<br />

examples of <strong>the</strong> design and layout of new, high<br />

quality, locally distinctive, development in rural<br />

areas can be found. It is <strong>the</strong> aspiration of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Dorset</strong> <strong>AONB</strong> Partnership that <strong>Reclaiming</strong> our<br />

<strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Highways</strong> will ensure that our rural road<br />

designs are as good as <strong>the</strong>se award-winning<br />

residential and mixed-use developments.<br />

1.4 Future steps<br />

1.4.1 <strong>Reclaiming</strong> our <strong>Rural</strong> <strong>Highways</strong> is divided into<br />

four sections.<br />

1.4.2 The first section provides an overview of <strong>the</strong> key<br />

issues. It shows how roads form an important part<br />

of <strong>Dorset</strong>’s landscapes and examines how road<br />

Executive Summary<br />

design can influence and alter <strong>the</strong> landscape and<br />

streetscape. It discusses how <strong>Dorset</strong>’s recognised<br />

success in designing new residential estates with<br />

innovative highway layouts can give pointers to<br />

improve rural road design.<br />

1.4.3 The second section discusses and evaluates <strong>the</strong><br />

wide range of problems that affect rural roads,<br />

and methods which have been applied to manage<br />

<strong>the</strong>m. The sometimes significant drawbacks to<br />

adopting traditional approaches are explained.<br />

Included are case study examples from<br />

elsewhere in <strong>the</strong> country that demonstrate<br />

sympathy with rural character, such as:<br />

• The de-cluttering initiatives in <strong>the</strong> Lake District;<br />

• The alternative methods of protecting and<br />

maintaining rural lanes in West Kent;<br />

• The trial to remove white carriageway centre line<br />

markings in Wiltshire villages;<br />

• Traditional fingerpost restoration and renewal in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Quantocks; and<br />

• The streetscape enhancements pioneered in Bury<br />

St Edmunds and o<strong>the</strong>r historic towns.<br />

1.4.4 The third section discusses <strong>the</strong> distinctive<br />

character of <strong>Dorset</strong>’s roads. There is a great<br />

variation in <strong>the</strong>ir character, from those across<br />

open heathland in Purbeck to <strong>the</strong> sunken lanes of<br />

West <strong>Dorset</strong>. A great deal of <strong>the</strong> character of<br />

<strong>the</strong>se roads emanates from <strong>the</strong> locally distinctive<br />

<strong>Dorset</strong> features which bound <strong>the</strong>m such as <strong>the</strong><br />

hedges, milestones and pre-1964 fingerposts.<br />

1.4.5 The fourth and concluding section advocates a<br />

series of recommendations for future action<br />

including:<br />

• <strong>the</strong> preparation of a guidance document to<br />

promote a better public realm through improved<br />

highway design which responds to local context<br />

and embraces local distinctiveness;<br />

• <strong>the</strong> creation of a hierarchy of highways – all of<br />

which respect <strong>the</strong> rural environment – and<br />

includes heavy vehicle, coach and tourist<br />

routeing, strategic co-ordination of direction<br />

signing for all vehicles and <strong>the</strong> reassessment of<br />

speed limits;<br />

• a checklist of items to take into account when<br />

undertaking projects which will affect rural roads;<br />

• <strong>the</strong> increased involvement of parish councils as<br />

local agents for positive change; and<br />

• <strong>the</strong> inclusion of policy statements in Local<br />

Transport Plans, Local Development Frameworks<br />

and Regional Spatial Strategies to reinforce <strong>the</strong><br />

need for action.<br />

Chapter 1: Executive Summary<br />

9

Section I: Overview of issues and problems<br />

Milton Abbas: Roads form part of <strong>Dorset</strong>’s famous built and natural heritage<br />

• Rationale for <strong>the</strong> study<br />

• Aim of <strong>the</strong> study<br />

• The importance of <strong>Dorset</strong>’s environment<br />

• The importance of <strong>Dorset</strong>’s rural roads<br />

• The importance of design<br />

• Insensitive design of rural roads<br />

• Policy context<br />

Chapter 1. Introduction

“The country road was once part of <strong>the</strong> distinctive and unspoiled character of our<br />

countryside, blending into <strong>the</strong> countryside Chapter and indistinguishable 1: Introduction from it...car drivers would<br />

'feel' <strong>the</strong> road and visually 'read' <strong>the</strong> road to determine <strong>the</strong> appropriate speed to travel... in<br />

recent decades <strong>the</strong> character of many rural roads has incrementally changed - more traffic...<br />

more kerbing and additional roadside clutter” [Friends of <strong>the</strong> Lake District (FLD) 2005:2]<br />

Chapter 2: Overview of issues and problems<br />

2.1 Rationale for <strong>the</strong> study<br />

2.1.1 Local authorities, along with a series of o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

bodies, have a statutory duty of care to Areas of<br />

Outstanding Natural Beauty (<strong>AONB</strong>s). Section 85<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Countryside & Rights of Way Act 2000<br />

states that:<br />

‘In exercising or performing any functions in<br />

relation to, or so as to affect, land in an area<br />

of outstanding natural beauty, a relevant<br />

authority [Minister of <strong>the</strong> Crown, public<br />

body, statutory undertaker or person holding<br />

public office] shall have regard to <strong>the</strong><br />

purpose of conserving and enhancing <strong>the</strong><br />

natural beauty of <strong>the</strong> area of outstanding<br />

natural beauty.’<br />

2.1.2 The same Act required a Management Plan to be<br />

prepared for each <strong>AONB</strong> area by <strong>the</strong> local<br />

authorities which covered <strong>the</strong>m. These Plans both<br />

set out issues affecting <strong>the</strong> area and ways in<br />

which <strong>the</strong>se are to be tackled. The consultation on<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Dorset</strong> <strong>AONB</strong> (D<strong>AONB</strong>) Draft Management<br />

Plan found that rural road management was a key<br />

concern and this led to incorporation of <strong>the</strong><br />

East Lulworth<br />

issue within <strong>the</strong> document. The vision of <strong>the</strong><br />

completed Plan notes that:<br />

‘With new approaches from practitioners<br />

and policymakers and a change in <strong>the</strong> way<br />

people use <strong>the</strong> road network, it can withstand<br />

<strong>the</strong> pressures put upon it by traffic and<br />

non-motorised users and remain a<br />

complementary element of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Dorset</strong> <strong>AONB</strong>.<br />

With a variety of travel options, <strong>the</strong> entire<br />

network of roads, footpaths, cycleways and<br />

bridleways toge<strong>the</strong>r with safe and convenient<br />

public transport provides sustainable access<br />

and movement around <strong>the</strong> <strong>AONB</strong>’ [D<strong>AONB</strong><br />

2004:42]<br />

As a result, a series of aims and policy objectives<br />

were included in <strong>the</strong> Management Plan on <strong>the</strong><br />

subject, as outlined in Table 2.1 on <strong>the</strong> next page.<br />

Chapter 2. Overview of issues and problems<br />

11

Chapter 2. Overview of issues and problems<br />

1212<br />

Section I: Overview of issues and problems<br />

The Management Plan set out <strong>the</strong> aims and<br />

objectives to improve rural road management<br />

techniques<br />

2.1.3 Table 2.1: Management Plan aims and<br />

objectives for rural roads[D<strong>AONB</strong> 2004:100]<br />

Aims<br />

• Provide sustainable travel options for residents<br />

and visitors<br />

• Reduce <strong>the</strong> impact of traffic within <strong>the</strong> <strong>AONB</strong><br />

and promote a better balance of road use<br />

• Ensure that <strong>the</strong> location and management of<br />

route and road corridors has regard to <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>AONB</strong> primary purpose of conserving and<br />

enhancing natural beauty<br />

Objectives<br />

Policy TR1<br />

Support <strong>the</strong> development of options for greater<br />

transport choice<br />

Policy TR2<br />

Develop and promote a fully integrated transport<br />

system that fulfils <strong>the</strong> needs of residents and<br />

visitors to <strong>the</strong> <strong>AONB</strong><br />

Policy TR3<br />

Support and develop initiatives that change<br />

priorities for road use on rural roads, making <strong>the</strong>m<br />

safer for non-car users<br />

Policy TR4<br />

Ensure that road design, delivery, signage and<br />

maintenance are sympa<strong>the</strong>tic to <strong>the</strong> special<br />

character of rural roads and <strong>the</strong> <strong>AONB</strong><br />

Policy TR6<br />

Ensure that <strong>the</strong> environmental and visual impact<br />

of car parking is minimised in <strong>the</strong> <strong>AONB</strong><br />

2.1.4 Current approaches to improving road design and<br />

<strong>the</strong> need for action were reviewed at <strong>the</strong> three<br />

respective Heritage Committees for North <strong>Dorset</strong>,<br />

Purbeck and West <strong>Dorset</strong> [West <strong>Dorset</strong> DC 2004,<br />

Purbeck DC 2004, North <strong>Dorset</strong> DC 2004].<br />

Positive feedback from <strong>the</strong>se led to <strong>the</strong><br />

commissioning of this study. A senior level<br />

meeting on <strong>the</strong> design and management of rural<br />

roads was held on <strong>the</strong> 27th January 2005 at <strong>the</strong><br />

Brownsword Hall in Poundbury, Dorchester to<br />

ensure <strong>the</strong> involvement of all <strong>the</strong> major agencies.<br />

2.1.5 It is now recognised that, in order to achieve<br />

acceptable levels of highway design quality, it<br />

is necessary to abandon what is sometimes<br />

termed <strong>the</strong> ‘Scalextric’ approach to design.<br />

Traditionally this has involved taking standard<br />

designs with predetermined cross-section widths<br />

and construction depths and implementing <strong>the</strong>se<br />

according to a rigid hierarchy. Traditionally each<br />

road type in a hierarchy had three components:<br />

• Firstly, it had standardised, prescribed, surface<br />

dimensions deemed sufficient to accommodate<br />

<strong>the</strong> volume and types of users identified as<br />

appropriate to its place in <strong>the</strong> hierarchy;<br />

• Secondly, it had to be structurally strong enough<br />

to withstand <strong>the</strong> axle loads imposed on it for a<br />

determined period;<br />

• Thirdly, it had basic visual characteristics<br />

determined by its function in <strong>the</strong> hierarchy.<br />

2.1.6 In short, <strong>the</strong> three components are:<br />

1. Width (dimensions and geometry)<br />

2. Depth (construction layers)<br />

3. Visual characteristics contributing to<br />

local distinctiveness<br />

2.1.7 The drive for higher quality design has<br />

necessitated a review of <strong>the</strong> approach taken to<br />

<strong>the</strong> third of <strong>the</strong>se components – <strong>the</strong> visual<br />

characteristics of <strong>the</strong> highway. This study<br />

principally examines how this third component<br />

can be used to influence driver behaviour and<br />

ensure <strong>Dorset</strong>’s rural roads are locally distinctive.<br />

2.1.8 This study specifically examines routes available<br />

for <strong>the</strong> public’s use across <strong>the</strong> D<strong>AONB</strong>. This<br />

comprises all public roads, including unmetalled<br />

ones, toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> Public Rights of Way<br />

(PROW) network of byways, bridleways and<br />

footpaths. Routes in small towns and villages are<br />

included, since <strong>the</strong>y sit within rural contexts<br />

[Roberts James, 2001]. It additionally has<br />

relevance for <strong>the</strong> A35 Trunk Road, which<br />

contains several sections of unimproved single<br />

carriageway (although rural Trunk Roads are not<br />

included in <strong>the</strong> Institute of <strong>Highways</strong> & Trunk

Section I: Overview of issues and problems<br />

Roads Transportation (IHT) definition of rural<br />

roads [Friends of <strong>the</strong> Lake District (FLD) 2005)].<br />

2.1.9 Although prepared for <strong>the</strong> D<strong>AONB</strong> Partnership,<br />

most of <strong>the</strong> principles – and solutions – examined<br />

have equal relevance for <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> rural<br />

county.<br />

2.2 Aim of study<br />

2.2.1 The study’s aims were as follows:<br />

(i) To collate information on methods used to<br />

manage rural routes elsewhere and assess <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

applicability to <strong>Dorset</strong>;<br />

(ii) To investigate route network hierarchies<br />

appropriate for <strong>the</strong> rural area;<br />

(iii) To characterise <strong>the</strong> rural routes in <strong>Dorset</strong><br />

according to <strong>the</strong>ir landscape character setting,<br />

historic development, or features critical to<br />

management;<br />

(iv) To identify streetscape features unique or<br />

special to <strong>Dorset</strong> requiring specific management<br />

or conservation; and<br />

(v) To recommend a way forward, including items for<br />

inclusion within a protocol or design guide document .<br />

2.3 The importance of <strong>Dorset</strong>’s<br />

environment<br />

2.3.1 In a recent survey, safeguarding <strong>Dorset</strong>’s unique<br />

environment was identified by residents as <strong>the</strong> top<br />

priority for action [<strong>Dorset</strong> Strategic Partnership<br />

2004]. <strong>Dorset</strong> is endowed with a great diversity of<br />

landscape character [Countryside Commission<br />

1999] and <strong>the</strong> county enjoys some of <strong>the</strong> highest<br />

quality rural and built environments in <strong>the</strong> country.<br />

2.3.2 This environmental quality is recognised with a<br />

range of designations to protect it. 53% of <strong>the</strong><br />

county is situated within Areas of Outstanding<br />

Natural Beauty (<strong>AONB</strong>s) – a proportion of <strong>the</strong><br />

county second only to that of East Sussex [<strong>Dorset</strong><br />

CC 2003]. 42% of <strong>the</strong> county is within <strong>the</strong> <strong>Dorset</strong><br />

<strong>AONB</strong> (D<strong>AONB</strong>) [<strong>Dorset</strong> CC 2004a] and 11% lies<br />

within <strong>the</strong> Cranborne Chase & West Wiltshire<br />

Downs <strong>AONB</strong>, which straddles <strong>the</strong> county<br />

boundary.<br />

2.3.3 The area covered by <strong>the</strong> D<strong>AONB</strong> is illustrated in<br />

Figure 2.1 overleaf. Broadly speaking, it stretches<br />

from Swanage in <strong>the</strong> east to Lyme Regis in <strong>the</strong><br />

west and from Beaminster to Blandford. This is a<br />

rich and varied landscape composed of chalk<br />

downland, heathland, coastal habitats and <strong>the</strong><br />

wetlands around Poole Harbour, giving <strong>the</strong> <strong>AONB</strong><br />

its special character. The D<strong>AONB</strong> Management<br />

Plan has an overall vision for <strong>the</strong> area to be:<br />

‘a thriving landscape of beauty, health and<br />

heritage that all can enjoy. An inspiration for<br />

today, an opportunity for tomorrow’<br />

[D<strong>AONB</strong> 2004:40]<br />

2.3.4 Much of <strong>the</strong> county has additional ecological,<br />

cultural heritage or landscape designations. The<br />

coastal fringe is a UNESCO-designated World<br />

Heritage Site; more generally <strong>the</strong> coastal areas<br />

are designated as Heritage Coasts. The county’s<br />

ecological diversity is acknowledged by <strong>the</strong><br />

designation of EU Special Areas of Conservation<br />

(SACs) and Special Protection Areas (SPAs),<br />

National Nature Reserves and Sites of Special<br />

Scientific Interest (SSSI). The built environment is<br />

protected by a significant number of listed<br />

building designations and many settlements<br />

have conservation areas. The national and<br />

international designations are a key attraction for<br />

visitors to <strong>Dorset</strong>.<br />

2.3.5 Looking after <strong>the</strong>se cherished landscapes is<br />

challenging and <strong>the</strong> importance of doing so is<br />

recognised in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Dorset</strong> Community Strategy:<br />

‘<strong>Our</strong> cultural and historic heritage is also<br />

important if we are to value and utilise our<br />

environmental resources in <strong>the</strong> widest sense.<br />

Restoration, renewal and appropriate<br />

management of <strong>the</strong> historic vernacular, built<br />

and natural environments must continue to<br />

be encouraged across all areas of<br />

<strong>Dorset</strong>….Ongoing measures must be taken to<br />

safeguard <strong>Dorset</strong>'s heritage including:<br />

research, understanding and protection of<br />

ancient monuments; maritime archaeology<br />

and listed buildings; supporting museums,<br />

managing and improving access to maps<br />

archives and records; protection of built<br />

heritage through conservation areas;<br />

appropriate development of towns and<br />

villages through enhancement schemes; and<br />

design guidance that set quality standards,<br />

respects local distinctiveness and<br />

encourages local provenance….Recognising<br />

<strong>the</strong> value of our landscapes is a beginning.<br />

However, conserving our environment both<br />

locally and globally is a serious concern that<br />

requires everyone to act responsibly.’<br />

[<strong>Dorset</strong> Strategic Partnership 2004:51]<br />

Chapter 2. Overview of issues and problems<br />

13

Chapter 2. Overview of issues and problems<br />

14 14<br />

Section I: Overview of issues and problems

Section I: Overview of issues and problems<br />

2.4 The importance of <strong>Dorset</strong>’s<br />

rural roads<br />

Chaldon Herring: Roads form part of <strong>Dorset</strong>’s<br />

protected landscapes<br />

2.4.1 The large network of rural roads reflects <strong>the</strong><br />

diversity of <strong>the</strong> landscape within which <strong>the</strong>y sit.<br />

They contribute to <strong>the</strong> special quality of <strong>Dorset</strong>’s<br />

rural environment [D<strong>AONB</strong> 2004] and are<br />

described as being ‘just as much a part of <strong>the</strong><br />

countryside as <strong>the</strong> fields and hedgerows’’<br />

[CPRE 1999]. Their manifold importance is noted<br />

in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Dorset</strong> <strong>AONB</strong> Management Plan, as follows:<br />

‘<strong>Dorset</strong>’s roads and routeways have evolved<br />

from long centuries of human use with great<br />

variations of style and character.<br />

Recognition of <strong>the</strong> importance of rural<br />

routes, <strong>the</strong> contribution <strong>the</strong>y make to<br />

people’s quality of life and <strong>the</strong>ir role in <strong>the</strong><br />

increasingly diverse rural economy is a key<br />

factor in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Dorset</strong> <strong>AONB</strong>. Roads are<br />

comfortably set within <strong>the</strong> landscape,<br />

complementing natural and cultural<br />

heritage. Many provide special habitats for<br />

plants and wildlife’ [D<strong>AONB</strong> 2004:42]<br />

2.4.2 The routes for movement in <strong>the</strong> countryside allow<br />

rural dwellers access to services and facilities and<br />

<strong>the</strong>y are used for <strong>the</strong> complete range of journey<br />

purposes [DETR & MAFF 2000]. This can be<br />

broken down into:<br />

• <strong>Rural</strong> to urban movements: functional trips<br />

including commuting<br />

• Urban to rural movements: reverse commuting<br />

and leisure visits to <strong>the</strong> countryside<br />

• Urban to urban movements: pressure on<br />

unimproved major roads and minor routes used<br />

for ‘rat running’<br />

• <strong>Rural</strong> to rural movements: functional daily travel<br />

between <strong>the</strong> local facilities [CA 2003b]<br />

They are used by a wide mix of transport modes<br />

which includes cyclists, walkers and horse riders<br />

as well as cars, motorbikes, buses and goods<br />

vehicles. The rural street or lane is a place for<br />

social interaction and a location for markets and<br />

fairs and is <strong>the</strong>refore an integral part of <strong>the</strong> rural<br />

community structure [Sustrans 2004a].<br />

South Street, Bridport: <strong>Rural</strong> streets are a location<br />

for markets and fairs<br />

2.4.3 This wide-ranging set of uses creates conflicts<br />

between users and a complex set of problems.<br />

Some attempts to deal with rural road<br />

problems, such as engineering improvements,<br />

can lead to secondary problems, such as fear and<br />

danger for non-motorised road users. The<br />

relatively poor rural public transport network<br />

implies that much long-distance travel will be<br />

achieved through personal, motorised mobility<br />

(private cars as well as, for instance, scooter<br />

schemes giving mobility to young people[CA<br />

2003a]). This affects rural road decision-making<br />

on issues such as acceptable vehicle speeds,<br />

pollution and ways in which roads can be shared<br />

between motorised and non-motorised users<br />

[D<strong>AONB</strong> 2004, CPRE 2004]. The assumption that<br />

personal mobility will remain dominant also<br />

has implications for funding. The complex web of<br />

problems which can afflict rural roads is illustrated<br />

in Figure 2.2 on page 14.<br />

Chapter 2. Overview of issues and problems<br />

15

Chapter 2. Overview of issues and problems<br />

16 16<br />

Section I: Overview of issues and problems<br />

Figure 2.2: The web of rural road problems<br />

2.4.4 In relation to o<strong>the</strong>r shire counties, <strong>Dorset</strong> is of an<br />

average size and has a small population;<br />

however, it is forecast to experience <strong>the</strong> second<br />

fastest population growth in England & Wales<br />

[<strong>Dorset</strong> CC 2003]. Reconciling <strong>the</strong> transport<br />

needs of <strong>the</strong> population with <strong>the</strong> desire to protect<br />

<strong>Dorset</strong>’s important natural and built environment<br />

is <strong>the</strong>refore one of <strong>the</strong> major issues for <strong>the</strong><br />

D<strong>AONB</strong>.<br />

2.4.5 Whilst an absence of motorways and<br />

lack of dual carriageways has reduced <strong>the</strong> large<br />

scale impacts of roads in <strong>the</strong> landscape, <strong>the</strong>re is<br />

increasing pressure on <strong>the</strong> rural road network as<br />

a whole. Proposals exist for new roads within <strong>the</strong><br />

D<strong>AONB</strong>, such as <strong>the</strong> A354 Dorchester Road<br />

Relief Road in Weymouth, and if built, this will<br />

impact on <strong>the</strong> South <strong>Dorset</strong> Ridgeway<br />

[D<strong>AONB</strong> 2004]. Despite generally low night-time<br />

light emissions across <strong>the</strong> D<strong>AONB</strong>, some of <strong>the</strong><br />

high emissions are attributable to street lighting.<br />

The prominent lighting of <strong>the</strong> Handley Cross<br />

roundabout is an o<strong>the</strong>rwise unlit area has<br />

led to it being known locally as <strong>the</strong> ‘UFO landing<br />

pad’ [Burden and Le Pard 1996].<br />

The A35 between Dorchester and Bere Regis is one<br />

of <strong>the</strong> few dual carriageways in <strong>the</strong> county, but<br />

where it ends, <strong>the</strong> trunk road reverts to unimproved<br />

single carriageway

Section I: Overview of issues and problems<br />

2.4.6 Across <strong>the</strong> county, <strong>the</strong> negative impacts of roads<br />

and traffic on rural communities and <strong>the</strong><br />

environment alike are keenly felt [<strong>Dorset</strong> <strong>AONB</strong><br />

2004]. Between 1977 and 1997 traffic volumes in<br />

<strong>Dorset</strong> have doubled [<strong>Dorset</strong> CC 1999: 40], and in<br />

similarity to <strong>the</strong> national pattern, <strong>the</strong> fastest traffic<br />

growth has taken place in rural areas [DETR &<br />

MAFF 2000, CPRE 2004]. Traffic continues to<br />

increase by 2.5% per year [D<strong>AONB</strong> 2004]. As<br />

congestion rises on <strong>the</strong> major road network,<br />

greater volumes of traffic are anticipated to ‘trickle<br />

down’ onto more minor routes [CA 2003a] and<br />

<strong>Dorset</strong>’s coastal areas in particular are already<br />

subject to great seasonal variations in traffic<br />

volume. Accident rates, too, are falling more<br />

slowly in rural areas than urban areas; those<br />

accidents that do occur are more likely to involve<br />

fatalities, regardless of <strong>the</strong> road user involved<br />

[DETR & MAFF 2000:65].<br />

A351, Sandford: traffic flows continue to rise<br />

on rural roads<br />

2.5 The importance of design<br />

Post-war residential estates have been criticised for<br />

having insufficient regard for highway design and<br />

local context<br />

2.5.1 Concern over <strong>the</strong> quality of <strong>the</strong> built and natural<br />

environment has mounted over recent years, with<br />

post-war residential estates – especially those<br />

from <strong>the</strong> 1970s and 1980s – having been<br />

particularly criticised as being anonymous,<br />

lacking in identity and inappropriate for rural<br />

settings [DTLR & CABE 2001]. Concern has also<br />

been growing regarding <strong>the</strong> deleterious effects of<br />

insensitive engineering improvements on rural<br />

roads. In both cases insufficient regard to design<br />

matters is held as <strong>the</strong> major cause.<br />

2.5.2 National guidance for local road design is<br />

currently fragmented. The Better Streets, Better<br />

Places [ODPM & DfT 2003] study, published in<br />

June 2003, investigated <strong>the</strong> connections between<br />

<strong>the</strong> application of rigid highway designs and <strong>the</strong><br />

successful development of quality, high density<br />

places. The authors found that no suitable<br />

guidance existed for ei<strong>the</strong>r dealing with existing<br />

rural roads or <strong>the</strong> design of proposed new roads<br />

for local traffic.<br />

2.6 Insensitive design of rural<br />

roads<br />

2.6.1 In <strong>the</strong> absence of o<strong>the</strong>r more suitable documents,<br />

design guidance intended for trunk roads (<strong>the</strong><br />

Design Manual for Roads and Bridges (DMRB))<br />

or residential estate roads (Design Bulletin 32<br />

(DB32)) has been inappropriately used. This was<br />

found to have compromised <strong>the</strong> quality of local<br />

roads, and in particular, <strong>the</strong>ir suitability for use by<br />

pedestrians and cyclists. Better Streets, Better<br />

Places also identified that insufficient emphasis<br />

has historically been placed on designing and<br />

managing streets which would be vibrant places<br />

in which people want to stop and spend time.<br />

There has instead been a concentration on<br />

simply designing routes for accommodating traffic<br />

movement and flow.<br />

2.6.2 The status of <strong>the</strong> various strands of guidance is<br />

often blurred. It has been noted that ‘what is<br />

frequently unclear are <strong>the</strong> circumstances in which<br />

[<strong>the</strong> installation of highway features] is required by<br />

law, is recommended in <strong>the</strong> form of official<br />

‘guidance’ or is simply highway engineers’ long<br />

established practice – or of increasing pertinence,<br />

where <strong>the</strong>ir installation might be deemed by a<br />

court of law, enjoying <strong>the</strong> benefit of hindsight after<br />

an accident, to be ‘reasonable’ [Adams 2005: 42].<br />

The latter point has risen in importance, with<br />

government recently consulting on <strong>the</strong><br />

introduction of a corporate manslaughter offence,<br />

which could lead to senior management being<br />

imprisoned for ‘conduct falling far below what can<br />

reasonably be expected of <strong>the</strong> corporation in <strong>the</strong><br />

circumstances’ [ibid: 43]<br />

2.6.3 Conflicting priorities between local highway and<br />

local planning authorities - often part of <strong>the</strong> same<br />

council – were found to lead to developments<br />

being recommended for planning approval, but<br />

being objected to by highway engineers following<br />

conventional highway design principles. The<br />

major reason behind this was that conventional<br />

Chapter 2. Overview of issues and problems<br />

17

Chapter 2. Overview of issues and problems<br />

18 18<br />

Section I: Overview of issues and problems<br />

<strong>Dorset</strong> has an extensive network of rural roads and tracks divided into a series of categories<br />

(illustrated above). However, <strong>the</strong>re is no guidance on <strong>the</strong> design and management which<br />

specifically relates to many of <strong>the</strong>se roads (see below).

Section I: Overview of issues and problems<br />

highway designs are well-established and<br />

considered easier to defend in a court of law,<br />

should a litigious claim be brought against <strong>the</strong><br />

authority. To smooth <strong>the</strong> progress of applications,<br />

house builders have often responded by avoiding<br />

innovation and bringing forward traditional layouts<br />

which tend to have lower dwelling densities and<br />

inherently higher traffic speeds [CABE & DfT 2003].<br />

2.6.4 Best practice case studies and <strong>the</strong> Better Streets,<br />

Better Places report have shown that:<br />

• Schemes should in <strong>the</strong> first instance be about<br />

creating successful places overall, not about<br />

tackling single issues;<br />

• Designers should consider all potential uses of<br />

<strong>the</strong> space;<br />

• Investment in quality and attention to detail can<br />

maximise a scheme's benefits;<br />

• Working toge<strong>the</strong>r is also fundamental to success<br />

- regardless of <strong>the</strong> professional background of <strong>the</strong><br />

contributors;<br />

• Good design can usually be achieved within<br />

existing regulations; and<br />

• Designers sometimes need to go back to first<br />

principles and look at <strong>the</strong> reasons behind<br />

guidance - ra<strong>the</strong>r than simply do things <strong>the</strong> way<br />

<strong>the</strong>y have always been done [ODPM & DfT 2003]<br />

2.7 Policy context<br />

2.7.1 This document is a timely contribution to <strong>the</strong><br />

increasing prominence being given to <strong>the</strong> subject<br />

of rural road management by policymakers.<br />

Recent years have seen a series of policy<br />

responses to <strong>the</strong> problem; at a national level, a<br />

series of research papers and guidance<br />

documents have investigated <strong>the</strong> subject of<br />

highway design. Many of <strong>the</strong>se showcased<br />

<strong>the</strong> successful developments in <strong>Dorset</strong>. Policy<br />

statements have stipulated <strong>the</strong> need to show<br />

greater regard for design in planning. Relevant<br />

documents are set out in Table 2.2 below.<br />

Table 2.2: Improving street design: major relevant policy, guidance and research documents<br />

Date Document Title Relevant aims or content of document<br />

Old-style Planning Policy Guidance Notes (PPGs) and new-style Planning Policy Statements (PPSs)<br />

2000 PPG3 Housing Design residential development which places needs of people before ease<br />

DETR of traffic movement and which creates attractive, high quality living environments<br />

2001 PPG13 Transport ‘The physical form and qualities of a place, shaped – and are shaped by – <strong>the</strong><br />

DETR way it is used and <strong>the</strong> way people and vehicles move through it…places that<br />

work well are designed to be used safely and securely by all in <strong>the</strong> community,<br />

frequently for a wide range of purposes and throughout <strong>the</strong> day and evening’<br />

2004 PPS7 Sustainable Development which respects and where possible enhances local distinctiveness<br />

development in and intrinsic qualities of <strong>the</strong> countryside<br />

rural areas ODPM<br />

2005 PPS1 Delivering Planning policies should promote high quality inclusive design in <strong>the</strong> layout of new<br />

Sustainable developments<br />

Development ODPM<br />

Guidance & Research<br />

1998 Places, Streets and Movement An companion guide to DB32 which gave examples of<br />

DETR innovative design approaches which met prescribed standards<br />

2000 By design–urban design in <strong>the</strong> planning Improving urban design quality<br />

process–towards better practice, DTLR & CABE<br />

2001 Better places to live – a companion guide Improving <strong>the</strong> quality of residential developments<br />

to PPG3, DTLR & CABE<br />

2002 Paving <strong>the</strong> way Critique of how to achieve clean, safe and attractive streets<br />

CABE & ODPM<br />

2003 Better Streets, Better Places Research project into relationship between application of<br />

ODPM & DfT highway standards and creation of well-designed places<br />

Chapter 2. Overview of issues and problems<br />

19

Chapter 2. Overview of issues and problems<br />

20 20<br />

Section I: Overview of issues and problems<br />

2.7.2 Of particular relevance to this study is Better<br />

Streets, Better Places. Its key recommendation<br />

was <strong>the</strong> production of a government-endorsed<br />

guidance document to deal comprehensively with<br />

<strong>the</strong> design, management and adoption of<br />

residential streets, to be known as <strong>the</strong> Manual for<br />

Streets (MfS) [McNulty 2004].<br />

Better Streets, Better Places recommended <strong>the</strong><br />

preparation of a Manual for Streets to raise <strong>the</strong><br />

standard of new and existing road design<br />

2.7.3 The MfS is expected to be a significant departure<br />

from many current design principles enshrined in<br />

existing guidance; it will thus supersede DB32,<br />

Places Streets and Movement and obviate <strong>the</strong><br />

need for <strong>the</strong> current plethora of local guidance.<br />

The local documents are often out-of-date and<br />

relevant sections of <strong>the</strong> existing guidance will be<br />

incorporated into <strong>the</strong> MfS. It is intended that <strong>the</strong><br />

DMRB need no longer be referred to when<br />

designing minor roads or those in residential<br />

areas. Whilst <strong>the</strong> MfS will provide a satisfactory<br />

approach to <strong>the</strong> nationwide issues of highway<br />

construction and geometry (components 1 and 2 of<br />

highway design), local distinctiveness varies from<br />

area to area and this will still require local input.<br />

2.7.4 According to a recent research document, ‘streets<br />

are essential components in <strong>the</strong> urban fabric, <strong>the</strong>y<br />

are places in <strong>the</strong>mselves, <strong>the</strong>y are <strong>the</strong> most<br />

immediate part of <strong>the</strong> public realm and we<br />

encounter <strong>the</strong>m everyday’ [CABE & ODPM 2002].<br />

Efforts to improve <strong>the</strong>m should not solely<br />

concentrate on reducing <strong>the</strong> effect of motor<br />

vehicles. The intention is for <strong>the</strong> MfS to raise <strong>the</strong><br />

quality of life through better minor road design<br />

and through a fundamental change in <strong>the</strong> way<br />

people share and enjoy <strong>the</strong> street. Its production<br />

should lead to design standards which create more<br />

people-orientated streets, community spaces and<br />

in which <strong>the</strong> needs of pedestrians and cyclists will<br />

be accorded a higher priority than present.<br />

Emphasis will be given to placemaking – creating<br />

successful places – and o<strong>the</strong>r issues, such as<br />

reducing crime and anti-social behaviour are<br />

taken into account.<br />

The Manual for Streets is intended to promote design<br />

which creates people-oriented places<br />

2.7.5 Although first envisaged as a tool for improving<br />

<strong>the</strong> design of new residential estate roads, many<br />

of <strong>the</strong> design principles which <strong>the</strong> MfS will contain<br />

will equally apply to o<strong>the</strong>r categories of road. Its<br />

application may include:<br />

• Re-design of existing roads;<br />

• Design of new roads;<br />

• Residential estate roads;<br />

• O<strong>the</strong>r residential roads;<br />

• Local distributor roads;<br />

• Roads in villages; and<br />

• Minor rural roads.<br />

2.7.6 Design codes are being considered by <strong>the</strong> Office<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Deputy Prime Minister (ODPM) as a way to<br />

both speed up <strong>the</strong> planning process and to ensure<br />

suitable forms of development are built.<br />

Adherence to good urban design principles<br />

assists in creating places where people want to<br />

live and work [CABE 2004] and design codes are<br />

seen as a technique to improve <strong>the</strong> quality of<br />

urban design [CABE 2004a, CABE 2004, Weaver<br />

2004], community engagement and speed of<br />

developments [CABE 2004]. They are described<br />

as a set of strict style rules [Weaver 2003].<br />

2.7.7 Design codes have previously been used in<br />

<strong>the</strong> United States and on some housing<br />

developments [CABE 2003, 2004]. Most famously<br />

<strong>the</strong>y have been used at Seaside, Florida (as<br />

featured in <strong>the</strong> film The Truman Show) and at<br />

Poundbury, Dorchester. Both developments<br />

adhere to strict design rules.

Section I: Overview of issues and problems<br />

2.7.8 Of particular interest for this study is that design<br />

code requirements can – amongst o<strong>the</strong>r things –<br />

stipulate street widths, distances between<br />

buildings [CABE 2003] and <strong>the</strong> design of streets<br />

and blocks, as well as sustainable urban<br />

drainage, urban design principles, building<br />

technologies, use of materials and energy<br />

efficiency [ODPM 2003]. The stipulation of local<br />

vernacular building styles in order to retain and<br />

streng<strong>the</strong>n local identities is an important<br />

component of design codes [ODPM 2003] and<br />

this has been highlighted by <strong>the</strong> government.<br />

Adopting successful schemes from o<strong>the</strong>r parts of<br />

<strong>the</strong> country will not foster local distinctiveness,<br />

concern being expressed that highlighting<br />

Poundbury as an example of design codes in<br />

action will lead to slavish copying elsewhere.<br />

This concern is reflected in comments that state it<br />

is ‘no good taking a code for Poundbury and<br />

dumping it in Hull’ [Weaver 2004].<br />

‘Poundbury is, perhaps, best described as a<br />

model urban extension for a <strong>Dorset</strong> county<br />

town. There are, of course, few of <strong>the</strong>se in<br />

England. In fact <strong>the</strong>re is just one’<br />

[Glancey 2004]<br />

Design codes can stipulate road widths and<br />

charcateristics [CABE 2005:34]<br />

2.7.9 The intention is for codes to be drawn up with<br />

stakeholders [ODPM 2004]. CABE stresses that<br />

design codes should cover <strong>the</strong> fundamentals and<br />

principles and not set rules like <strong>the</strong> ‘Poundbury<br />

pattern book’ [Weaver 2003]. To this end,<br />

information should not be ‘so prescriptive as to<br />

smo<strong>the</strong>r creativity’ [CABE 2003].<br />

2.7.10 The ODPM launched its pilot programme in May<br />

2004 of 8 pilot schemes [CABE 2004, 2004a]. The<br />

different pilots will test whe<strong>the</strong>r design codes:<br />

• Relate well to <strong>the</strong> planning system<br />

• Help in areas of multiple land ownership and with<br />

several developers<br />

• Improve <strong>the</strong> housing quality produced by national<br />

housebuilders<br />

• Work well at a large scale<br />

• Can produce new development which reflects<br />

local distinctiveness<br />

• Can improve upon existing masterplans<br />

2.7.11 Initial findings indicate that developments planned<br />

using design codes are of higher quality -<br />

although <strong>the</strong>y are also characterised by both a<br />

strong initial commitment to design from <strong>the</strong><br />

outset and strong leadership. The initial time<br />

spent on <strong>the</strong> codes brings dividends later<br />

on <strong>the</strong> planning process, with compliant planning<br />

applications having a smooth ride through <strong>the</strong><br />

permission process. This also applies to <strong>the</strong> time<br />

and effort spent involving people from different<br />

professional backgrounds.<br />

2.7.12 Formalising <strong>the</strong> design codes ei<strong>the</strong>r as Local<br />

Development Orders (where local planning<br />

authorities selectively relax permitted<br />

development rights with development quality<br />

assured through <strong>the</strong> use of codes),<br />

Supplementary Planning Documents or Area<br />

Action Plans through <strong>the</strong> new planning process<br />

are each considered to have merit [ODPM 2003,<br />

CABE 2005].<br />

2.7.13 The development of design codes is in its infancy<br />

and <strong>the</strong>ir application o<strong>the</strong>r than for <strong>the</strong> design of<br />

major housing developments has not been<br />

trialled. They do however indicate <strong>the</strong><br />

government’s approval of <strong>the</strong> use of strict<br />

guidelines for design in <strong>the</strong> statutory land use<br />

planning process. This could pave <strong>the</strong> way for<br />

similar documents covering <strong>the</strong> design of rural<br />

roads through <strong>the</strong> Supplementary Planning<br />

Documents process. The need both for local<br />

distinctiveness (both a key part of <strong>the</strong> D<strong>AONB</strong>’s<br />

attractiveness and often mentioned in rural road<br />

management documents) and community<br />

Chapter 2. Overview of issues and problems<br />

21

Section 1. Overview of issues and problems<br />

22 22<br />

Section I: Overview of issues and problems<br />

involvement is stressed in design coding<br />

documents. These concepts in particular can be<br />

applied to any rural road management documents<br />

produced for <strong>the</strong> D<strong>AONB</strong>.<br />

The CoastLinx 53 is becoming a popular method for<br />

visitors to explore <strong>the</strong> environmentally sensitive<br />

Jurassic Coast<br />

2.7.14 The subject of managing travel generally in rural<br />

areas is growing in importance in <strong>Dorset</strong> and<br />

is being recognised by <strong>Dorset</strong>’s local authorities<br />

and agencies. The recent designation of <strong>Dorset</strong>’s<br />

Jurassic Coast as a World Heritage<br />

Site by UNESCO means that visitor management<br />

and sensitive approaches to transport within <strong>the</strong><br />

coastal hinterland is of heightened importance. In<br />

parallel a recent government announcement<br />

indicated that ‘urban design and liveability will be<br />

at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> next round of Local Transport<br />

Plans’ [McNulty 2004] and this too will have<br />

implications for rural roads.<br />

2.7.15 Additional focus in new Local Transport Plans on<br />

rural areas more generally – with policies to<br />

protect and enhance <strong>the</strong> countryside character of<br />

rural lanes – is viewed by some as a necessary<br />

alteration [CPRE 2004]. This would be a<br />

departure from <strong>the</strong> low prominence traditionally<br />

accorded to rural transport issues in <strong>the</strong> first<br />

round of LTPs [Headicar & Jones 2002].<br />

2.7.16 It is intended that <strong>Dorset</strong> County Council’s 2nd<br />

LTP will included strategies and policies which<br />

afford protection to and promote enhancement for<br />

<strong>the</strong> rural road network, in line with government<br />

aspirations. LTP strategy in this field is likely to<br />

concentrate on ensuring that:<br />

• Transport improvements complement <strong>Dorset</strong>’s<br />

high environmental quality and improve <strong>the</strong> public<br />

realm in a locally distinctive way<br />

• The impact of transport on <strong>the</strong> natural, built and<br />

cultural environment is reduced<br />

• Sustainable access options are provided to<br />

<strong>Dorset</strong>’s visitor attractions, especially <strong>the</strong> World<br />

Heritage Site<br />

2.7.16 The wide variety of policy responses by a series<br />

of different agencies illustrates that rural road<br />

management is more than just an issue of<br />

highway design. The problems are not solely <strong>the</strong><br />

remit of any one authority and many documents<br />

highlight <strong>the</strong> complementary roles that <strong>the</strong> local<br />

highway authority and local planning authority in<br />

particular have to play. There is interaction not<br />

only between well-designed streets and well<br />

designed places but sympa<strong>the</strong>tic rural road<br />

management and conservation, preservation and<br />

enjoyment of <strong>Dorset</strong>’s environment.

Section II: Evaluation of rural road<br />

management methods<br />

A wide range of methods have been trialled to<br />

address rural road issues and <strong>the</strong>se are examined<br />

in this section. The following responses to problems<br />

are discussed in eight chapters, as follows:<br />

• De-cluttering and quality design;<br />

• Protecting <strong>the</strong> natural and built environment;<br />

• Managing traffic: traffic calming and<br />

traditional measures;<br />

• Managing traffic: innovative measures;<br />

• Route functions: which routes for which users?<br />

• Route functions: non-motorised users;<br />

• Policy, guidance and hierarchies; and<br />

• Maintaining <strong>the</strong> roads.<br />

Each chapter examines <strong>the</strong> problems encountered and<br />

examples of potential solutions and best practice as<br />

trialled across <strong>the</strong> UK and overseas.<br />

23

“The car and commerce are both vital to <strong>the</strong> well-being of <strong>the</strong> country,<br />

but it is <strong>the</strong> junk <strong>the</strong>y trail with <strong>the</strong>m that we have to tackle”<br />

Chapter 3. De-cluttering and quality design 24<br />

Prince of Wales 1989: 94<br />

Chapter 3: De-cluttering and quality design<br />

3.1 Introduction to chapter<br />

…It's all too easy to over design for safety.<br />

It's good practice for example, to review<br />

signing periodically. One, to ensure signs are<br />

still appropriate for <strong>the</strong>ir intended purpose.<br />

And two, to take into account changes in<br />

regulatory requirements. But good design<br />

can entail minimising sign clutter or<br />

rearranging street furniture without<br />

necessarily compromising road safety. And<br />

as has been evidenced, even small<br />

changes and small schemes can have a<br />

positive impact on <strong>the</strong> local environment and<br />

on passers by…. I'm confident specialists<br />

from different fields can work toge<strong>the</strong>r to<br />

achieve broader benefits than those possible<br />

through working in isolation.”<br />

[McNulty 2004]<br />

3.1.1 Whilst large, modern roads create <strong>the</strong> most<br />

intrusive engineered impact on <strong>the</strong> landscapes<br />

generally, <strong>the</strong> cumulative impact of small changes<br />

on more minor roads can also be significant<br />

[Chilterns <strong>AONB</strong> 1997]; especially in protected<br />

landscapes where major developments are rare<br />

Red Post, Winterborne Zelston:<br />

a forest of signs degrades <strong>the</strong><br />

rural environment<br />

[North Pennines <strong>AONB</strong> 2004]. Bright colours,<br />

geometric shapes and straight lines look out of<br />

place [Chilterns <strong>AONB</strong> 1997]; alterations to road<br />

signage, kerbing, lighting and traffic calming can<br />

all contribute to <strong>the</strong> changing character of roads<br />

[D<strong>AONB</strong> 2004] and to subsequent creeping<br />

urbanisation [CPRE 2004]. It is noted that ‘each<br />

intrusion on its own may seem innocuous but<br />

overall we lose a sense of rural character’<br />

[CPRE 2004].<br />

The problem of clutter has been recognised for<br />

many years, such as in this cartoon by Osbert<br />

Lancaster [from Prince of Wales 1989]

Section II: Evaluation of rural road management methods<br />

3.1.2 Blame is attributed to slavish adherence to<br />

standards, <strong>the</strong> requirement for cost efficiency (to<br />

<strong>the</strong> detriment of quality) and litigation concerns<br />

leading to every danger being highlighted.<br />

However, over-signing in itself may dilute<br />

important road safety messages [Sustrans 2004a]<br />

and <strong>the</strong>re is little statistical evidence to prove that<br />