Fresh Drinking Water - Stadtwerke Düsseldorf AG

Fresh Drinking Water - Stadtwerke Düsseldorf AG

Fresh Drinking Water - Stadtwerke Düsseldorf AG

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Fresh</strong><br />

drinking<br />

water round<br />

the clock

<strong>Water</strong> –<br />

Essence<br />

of Life<br />

From time immemorial mankind’s<br />

destiny has been closely<br />

linked with water. Civilised<br />

races and empires thrived in<br />

those climes where water was<br />

available. Even nowadays<br />

those regions with a balanced<br />

water supply continue to be<br />

in a more favourable position<br />

than those with little water<br />

or arid regions: industrialization<br />

and the quality of life<br />

clearly depend on the availability<br />

of clean water, and the<br />

latter is by no means evenly<br />

distributed over the globe.<br />

Daily per capita consumption<br />

of drinking water in Germany<br />

is some 128 litres – in contrast,<br />

a family of six in<br />

Ethiopia has a mere 16 litres<br />

at its disposal, and is compelled<br />

to undertake a twohour<br />

walk, carrying the water<br />

home in jerry cans. Only 20%<br />

of all households in the world<br />

are connected up to a central<br />

water system, which is available<br />

as a matter of course to<br />

ourselves.

What is so unique about this<br />

unexceptional substance<br />

“water”?<br />

From a purely chemical<br />

point-of-view water is a<br />

molecule from hydrogen and<br />

oxygen with the formula<br />

H O. This molecule has two<br />

2<br />

poles, that is a positive<br />

partial-charge in the case of<br />

hydrogen and a negative<br />

partial-charge in the case<br />

of oxygen. This so-named<br />

“dipole formation” is<br />

responsible for many of<br />

water’s characteristics.<br />

<strong>Water</strong> is an element, which<br />

exists in nature in three<br />

different forms, the states<br />

of aggregation: as a solid,<br />

a fluid and a gas.<br />

<strong>Water</strong> is the only fluid<br />

which expands when its<br />

temperature drops. Its maximum<br />

density is attained at<br />

+4° Celsius.<br />

The fact that the density of<br />

ice is less than its fluid form<br />

is known as the “density<br />

anomaly”.<br />

Thus water is heavier than<br />

ice. If this were not the case,<br />

water in its various forms<br />

would freeze from the bottom<br />

upwards, leading to destruction<br />

of all underwater<br />

life.<br />

<strong>Water</strong> is an excellent solvent<br />

and, as an accumulator of<br />

heat, a significant climatic<br />

factor as can be seen in the<br />

case of the Golf Stream.<br />

Two thirds of the human<br />

body consist of the substance<br />

water.<br />

We could not live without<br />

water. A human being can<br />

survive for several weeks<br />

without food, but only a few<br />

days without water.

The<br />

Blue<br />

Planet<br />

Almost three quarters of the<br />

earth’s surface (71 percent) is<br />

covered by water, the world’s<br />

total water amounts to some<br />

1.5 billion cubic kilometres.<br />

Not one single drop of this<br />

huge volume of water is lost,<br />

no matter how or for what<br />

purpose the water is used:<br />

Above oceans and land the<br />

surface water is evaporated<br />

by the sun, this then is<br />

changed into water vapour.<br />

The water vapour rises and<br />

condenses to form clouds,<br />

which in their turn pass back<br />

their moisture as rain, dew,<br />

snow or hail, returning once<br />

again to the evaporation<br />

process from the oceans,<br />

lakes and rivers – the neverending<br />

water cycle.<br />

However 97.2 percent of<br />

total water supplies is salt<br />

water and consequently is<br />

not available as drinking<br />

water, at least not directly.<br />

Thus, this leaves 2.8 percent<br />

freshwater, but the bulk of<br />

this is frozen water to be<br />

found in the polar ice caps<br />

and glacier ice as well as<br />

being confined to the atmosphere.<br />

A mere 0.7 percent<br />

of total water on the earth is<br />

immediately available as a<br />

drinking water resource.

With a mean average annual<br />

precipitation of 790 millimetres<br />

Germany is a region<br />

with an abundance of water<br />

(this is the equivalent of a<br />

volume of 790 litres per<br />

square metre). Taking into<br />

account the loss of water due<br />

to evaporation and flowing<br />

to neighbouring countries<br />

and allowing for water flowing<br />

into Germany from the<br />

latter, the water resources<br />

available in our country is<br />

182 billion cubic metres.<br />

The <strong>Water</strong> Budget illustrates<br />

how this volume is split up<br />

between the consumer<br />

groups. It is obvious that<br />

public sector water supplies,<br />

amounting to some 5.7<br />

billion cubic metres annually,<br />

represents only a small proportion.<br />

At the same time it<br />

is apparent from this Budget<br />

that less than a quarter of<br />

the total amount available is<br />

actually used – therefore we<br />

have no problems regarding<br />

lack of water.<br />

Of greater significance is the<br />

threat to drinking water resources<br />

from industry (waste<br />

water from production processes),<br />

agriculture (soil<br />

penetration of fertilisers and<br />

pesticides) and private households<br />

(two million tons of<br />

household cleaners and detergents<br />

annually). The waterworks<br />

are concerned about<br />

having to invest even more<br />

money in the future in order<br />

to be able to supply drinking<br />

water with the required<br />

quality.<br />

With this in mind <strong>Stadtwerke</strong><br />

<strong>Düsseldorf</strong> actively supports<br />

the appeal made by the<br />

Association of <strong>Water</strong>works in<br />

the Rhine Catchment Area<br />

(IAWR):<br />

The quality of surface water<br />

is intended to be sufficiently<br />

high to permit only<br />

natural methods for treatment<br />

of drinking water.

<strong>Düsseldorf</strong> –<br />

the <strong>Water</strong> Supply<br />

The <strong>Stadtwerke</strong> <strong>Düsseldorf</strong><br />

waterworks supply over<br />

600.000 people in <strong>Düsseldorf</strong><br />

and Mettmann with an<br />

average of 150.000 cubic<br />

metres of drinking water a<br />

day – that is 150 million<br />

litres. (As an illustration,<br />

that is the equivalent of<br />

750.000 bath tubs, each<br />

holding 200 litres). The<br />

water supplied can vary between<br />

120.000 cubic metres<br />

on a winter’s day and<br />

200.000 cubic metres on a<br />

hot day in summer.<br />

Even then there are no<br />

problems. Maximum capacity,<br />

otherwise known as<br />

”bottleneck capacity”, is in<br />

the region of 252.000 cubic<br />

metres per day. In addition<br />

to this almost 120.000 cubic<br />

metres are retained in four<br />

reservoirs, where brisk stirring<br />

and intermingling of<br />

the water ensures consistent<br />

quality.<br />

<strong>Water</strong> supply is maintained<br />

by three waterworks:<br />

“Holthausen” waterworks in<br />

the south of the city, where<br />

the laboratory responsible for<br />

quality maintenance and supervision<br />

is located.<br />

“Flehe” waterworks, in the<br />

vicinity of the Heine-University,<br />

which in 1870 was the<br />

nucleus of the central supply<br />

of water in <strong>Düsseldorf</strong>.<br />

“Am Staad” waterworks to<br />

the north of the trade fair<br />

grounds, which is the control<br />

centre for the Rhine leftbank<br />

emergency waterworks<br />

“Lörick”.<br />

In order to ensure adequate<br />

supplies of water the <strong>Düsseldorf</strong><br />

waterworks, for instance,<br />

are linked up with<br />

the Great Dhünn Valley Dam,<br />

the ground water extraction<br />

facility of the lignite mining<br />

area and the waterworks of<br />

other towns in the vicinity.

<strong>Water</strong> Supply in<br />

<strong>Düsseldorf</strong> involves<br />

three distinct stages:<br />

<strong>Water</strong> Production<br />

<strong>Water</strong> Processing<br />

<strong>Water</strong> Distribution<br />

<strong>Water</strong> Production<br />

The wells of our waterworks<br />

produce a natural water,<br />

approximately a quarter of<br />

which consists of ground<br />

water and some three quarters<br />

of Rhine water seepage;<br />

these proportions can vary<br />

somewhat, depending on the<br />

water level of the Rhine.<br />

The river water seeps off at<br />

the bottom in the middle of<br />

the Rhine river bed and runs<br />

slowly in the direction of the<br />

bank. The passage through<br />

the bank and layers of sand

Rhine<br />

water-bearing<br />

gravel and sand strata<br />

water-carrying bed<br />

local water table<br />

lowered ground<br />

water table<br />

well<br />

pump<br />

and gravel, up to 30 metres<br />

thick, can take several weeks<br />

until the water reaches the<br />

well pumps. During this period<br />

the water is purified<br />

twice over: firstly the gravel<br />

and sand function as a mechanical<br />

filter, holding back<br />

dirt and turbid substances.<br />

Secondly micro-organisms,<br />

minute forms of life, eliminate<br />

a large number of substances.<br />

This natural biological<br />

process prevents the<br />

slotted pipes<br />

pipe to processing plant<br />

ground water from<br />

Rhine-Berg-District<br />

layers of soil from being burdened<br />

with harmful substances<br />

and thereby depriving<br />

them of their function – in<br />

actual fact the bacteria live<br />

off substances that the<br />

drinking water can well do<br />

without by destroying them.<br />

Thus the water at the pump<br />

well (known as “raw water”)<br />

is of high quality, even at this<br />

early stage.<br />

The pumps in the well lines<br />

extend down to a depth of<br />

30 metres and cause the<br />

subterranean water table to<br />

drop. In this way there is an<br />

uninterrupted flow of water<br />

to the wells The water is<br />

drawn in via pipes with slotshaped<br />

openings and pumped<br />

into the waterworks via<br />

collector pipes.

<strong>Water</strong> Processing<br />

Processing the raw water<br />

is achieved by means of<br />

the “<strong>Düsseldorf</strong> Process”,<br />

a process which has been<br />

developed by the <strong>Düsseldorf</strong><br />

waterworks .<br />

First of all the water flows<br />

through a contact tank and<br />

ozone (O ), this is the highly-<br />

3<br />

active trivalent form of oxygen,<br />

is added to it. Ozone<br />

functions as a highly effective<br />

disinfectant and transforms<br />

organic and inorganic<br />

substances into flaky precipitants,<br />

which can be readily<br />

filtered off. In particular<br />

these are iron and manganese<br />

compounds. Simultaneously,<br />

odours and tastes,<br />

which can affect the quality<br />

of the drinking water are<br />

removed.<br />

The ozone treated water is<br />

retained in an intermediate<br />

tank for some 30 minutes<br />

for a further reaction. Any<br />

substances which have not<br />

been previously treated are<br />

then converted. The residual<br />

ozone leaves the tank via a<br />

catalytic converter and is<br />

passed back to the air as<br />

normal oxygen are now<br />

converted.<br />

The third step in the processing<br />

chain is the filtration.<br />

The water is pumped into<br />

a steel tank filled with two<br />

layers of carbon. As the water<br />

seeps through the 1.5<br />

metre deep upper layer the<br />

flaky precipitation is removed<br />

and organic substances<br />

microbiologically eliminated.<br />

When in due course the efficacy<br />

of the filtration process<br />

deteriorates the carbon is<br />

washed. The sludge rinsed<br />

out holds a high proportion<br />

of carbon shavings and is<br />

incinerated.

ozone gas<br />

from ozone<br />

unit<br />

injector<br />

motive water<br />

catalyctic converter<br />

for removal of<br />

residual ozone<br />

natural water inlet contact tank intermediate tank active carbon tank<br />

The second layer, 2.5 metres<br />

deep consists of active<br />

carbon, a very fine and<br />

extremely porous granulate.<br />

Organic chlorine compounds,<br />

odours and tastes<br />

and other undesirable substances<br />

are retained in the<br />

capillary tubes. As soon as<br />

50% of the active carbon is<br />

affected by residues, the<br />

layer is removed and replaced<br />

by fresh carbon. The<br />

carbon is cleansed by calcination<br />

at a temperature of<br />

700 to 800 °C in its own<br />

reactivation unit.<br />

The active carbon is removed<br />

immediately and replaced by<br />

fresh activated carbon, if the<br />

waterworks report abnormal<br />

or hazardous incidents of<br />

pollution of Rhine water.<br />

pump<br />

chlorine<br />

dioxide<br />

phosphate/<br />

silicate<br />

upper<br />

layer<br />

lower<br />

layer<br />

carbon<br />

removal<br />

vent<br />

drinking water<br />

outlet to network<br />

The fourth and last step<br />

involves adding a phosphatesilicate<br />

mixture to the water,<br />

initially in small doses<br />

(1 mg/l) in order to prevent<br />

damage to the pipes from<br />

corrosion.<br />

Finally 0.06 mg/l chlorine<br />

dioxide is added to prevent<br />

the formation of bacteria in<br />

the water. The water undergoes<br />

a constant check for a<br />

large number of substances<br />

which it might contain, not<br />

only before it enters the network,<br />

but also after it is in<br />

the system for the purposes<br />

of complying with the regulations<br />

of the <strong>Drinking</strong><br />

<strong>Water</strong> Act. In this way our<br />

customers can expect excellent<br />

drinking water round<br />

the clock.

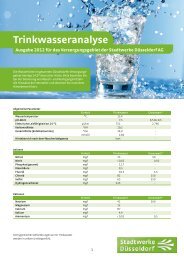

Extract from the <strong>Düsseldorf</strong> <strong>Drinking</strong> <strong>Water</strong> Analysis<br />

2002 2003<br />

<strong>Water</strong> temperature 13.1 °C 12.9 °C<br />

pH value 7.2 mg/l 7.23 mg/l<br />

Total hardness 14.1 °dH 15.7 °dH<br />

Hardness range 3.0 3.0<br />

Calcium 89.0 mg/l 92.0 mg/l<br />

Magnesium 11.4 mg/l 23.0 mg/l<br />

Sodium 37.0 mg/l 39.0 mg/l<br />

Potassium 4.5 mg/l 4.3 mg/l<br />

Sulphate 63.0 mg/l 62.0 mg/l<br />

Chloride 71.0 mg/l 73.0 mg/l<br />

Nitrate 15.4 mg/l 16.2 mg/l<br />

Phosphate 1.1 mg/l 1.02 mg/l<br />

<strong>Water</strong><br />

Distribution<br />

A 1.800 kilometre pipe network<br />

extends throughout<br />

the water supply area. With<br />

a diameter of one metre the<br />

pipes leave the waterworks,<br />

eventually finding their way<br />

to the end consumer’s<br />

home, reducing to some<br />

15 - 20 millimetres in diameter.<br />

The pipes undergo<br />

regular checks, are cleaned<br />

and, if necessary, replaced.<br />

In this way damage can be<br />

identified in time before it<br />

leads to leakage and loss in<br />

the network.<br />

Furthermore the quality of<br />

water in the pipes is under<br />

constant supervision: every<br />

day samples are taken at<br />

80 different observation<br />

stations and tested by our<br />

laboratory. All of the test<br />

readings are registered and<br />

monitored by the Municipal<br />

Health Office.<br />

An in-depth analysis of the<br />

drinking water can be<br />

obtained under the<br />

following telephone number<br />

from the utilities at any<br />

time of the day:<br />

+49 (211) 821 821 or<br />

www.swd-ag.de

International<br />

Cooperation<br />

The Rhine has undergone<br />

radical change since the<br />

fifties and these are still<br />

of great significance as far<br />

as production of drinking<br />

water is concerned.<br />

The waterworks have<br />

merged into regional<br />

confederations in order to<br />

promote their own interests<br />

and requirements.<br />

In 1950 the Dutch set up<br />

RIWA (Rijncommissie<br />

<strong>Water</strong>leidingsbedrijven), in<br />

1957 the German waterworks,<br />

extending to the<br />

mouth of the Neckar, established<br />

ARW (Association of<br />

the Rhine-<strong>Water</strong>works) and<br />

in 1968 the south German,<br />

French and Swiss water<br />

suppliers launched AWBR<br />

(Association of the Lake<br />

Constance-Rhine <strong>Water</strong>works).<br />

In order to consolidate the<br />

resources of the individual<br />

confederations and to act in<br />

unison whilst promoting<br />

the interests of the water<br />

industry at the European<br />

Union, IAWR was founded<br />

in 1970 in <strong>Düsseldorf</strong><br />

(Internationale Association<br />

of <strong>Water</strong>works in the Rhine<br />

Catchment Area). Currently<br />

120 waterworks from seven<br />

countries are members of<br />

IAWR.

Protection for<br />

valuable resources<br />

<strong>Drinking</strong> water is exposed<br />

to numerous hazards. It<br />

should not be overlooked<br />

that a constant strain on<br />

resources, entailing even<br />

only minute quantities, can<br />

be a greater burden than a<br />

temporary high concentration<br />

of harmful substances<br />

caused by an accident at a<br />

chemical plant. Thus this a<br />

is a challenge to each and<br />

everyone of us. We have to<br />

reconsider our attitudes<br />

radically: Nowadays it is all<br />

too convenient to strew<br />

weed killers where in former<br />

times the weeds were simply<br />

pulled up from the garden.<br />

People resort to any of<br />

the countless home care<br />

products available rather<br />

than taking the trouble to<br />

keep the home clean, just<br />

using water, brush and floor<br />

cloths. This should not<br />

however obscure one’s view<br />

regarding practical quality<br />

requirements for production<br />

of drinking water. If it is a<br />

generally accepted fact that<br />

these products can be used,<br />

it is unreasonable to expect<br />

the waterworks to function<br />

as a technical helpdesk for<br />

the purposes of remedying<br />

harm caused to the<br />

environment.<br />

Much has been achieved to<br />

protect the Rhine as our<br />

major source of drinking<br />

water. A number of waterworks<br />

confederations set up<br />

an early warning system as<br />

early as 1960, which informs<br />

all the participants of<br />

any significant incidents in<br />

a link-up from Basel to<br />

Rotterdam. Furthermore a<br />

fleet of so-named “bilge-oil<br />

extraction vessels” has been<br />

established. These vessels<br />

collect the bilge oil, which<br />

accumulates in the bilge of<br />

a vessel and dispose of it<br />

efficiently and free of<br />

charge. Last, but not least,<br />

these confederations carry<br />

out research projects, involving<br />

not inconsiderable expense<br />

and academic support<br />

in order to improve the<br />

water quality – but, nevertheless,<br />

what has been<br />

achieved to date can only<br />

be preserved and enhanced<br />

if everybody makes a contribution.

Imprint<br />

Publishers<br />

<strong>Stadtwerke</strong> <strong>Düsseldorf</strong> <strong>AG</strong><br />

Abteilung Öffentlichkeitsarbeit<br />

Höherweg 100<br />

40233 <strong>Düsseldorf</strong><br />

Phone: +49 (211) 821 821<br />

Internet: http//www.swd-ag.de<br />

E-Mail: pbeardsley@swd-ag.de<br />

Text<br />

Michael Pützhofen,<br />

<strong>Stadtwerke</strong> <strong>Düsseldorf</strong> <strong>AG</strong><br />

Concept, Layout and Illustration<br />

Palmer Jurk Design, Meerbusch<br />

Picture Credits<br />

– SWD-Archiv<br />

– Stockbyte<br />

– Goodshoot<br />

– Adobe<br />

– Photo of the earth with<br />

kind permission of NASA B-102/99/12.02