REZUMATUL - USAMV Cluj-Napoca

REZUMATUL - USAMV Cluj-Napoca

REZUMATUL - USAMV Cluj-Napoca

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

UNIVERSITATEA DE ŞTIINŢE<br />

AGRICOLE ŞI MEDICINĂ<br />

VETERINARĂ, CLUJ-NAPOCA<br />

FACULTATEA DE ZOOTEHNIE ŞI<br />

BIOTEHNOLOGII<br />

DOMENIUL: BIOTEHNOLOGII<br />

<strong>REZUMATUL</strong><br />

TEZEI DE DOCTORAT<br />

SISTEME DE ÎNCAPSULARE A UNOR COMPUŞI<br />

BIOACTIVI EXTRAŞI DIN ULEIURI VEGETALE<br />

MONICA TRIF<br />

Ing. Dipl. Biotehnolog<br />

CONDUCĂTOR ŞTIINŢIFIC:<br />

PROF. Dr. Dr. h.c. HORST A. DIEHL<br />

2009

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

CUPRINS<br />

I. INTRODUCERE. SCOP ŞI OBIECTIVE............................................................................ III<br />

PARTEA II. CONTRIBUŢII PROPRII (ORIGINALE) .........................................................IX<br />

CAPITOL II. CARACTERIZAREA ULEIURILOR FUNCŢIONALE UTILIZATE LA<br />

BIOÎNCAPSULARE ...............................................................................................................IX<br />

II.1. MATERIALE ŞI METODE .........................................................................................IX<br />

II.2. REZULTATE ŞI DISCUŢII.......................................................................................... X<br />

II.3. CONCLUZII .............................................................................................................. XIV<br />

CAPITOLUL III. BIOÎNCAPSULAREA ULEIURILOR: PROTOCOALE DE PREPARE A<br />

CAPSULELOR ŞI CARACTERIZAREA LOR.................................................................... XV<br />

III.1. MATERIALE ŞI METODE...................................................................................... XV<br />

III.2. REZULTATE ŞI DISCUŢII .................................................................................... XVI<br />

III.3. CONCLUZII............................................................................................................XXII<br />

CAPITOL IV. EFICIENŢA ÎNCAPSULĂRII ŞI STUDII DE ELIBERARE A ULEIURILOR<br />

DIN CAPSULE....................................................................................................................XXII<br />

IV.1. MATERIALE ŞI METODE....................................................................................XXII<br />

IV.2. REZULATTE ŞI DISCUŢII ................................................................................. XXIII<br />

IV.3. CONCLUZII ......................................................................................................... XXVI<br />

CAPITOL V. CARACTERIZAREA FTIR A OXIDĂRII ULEIURILOR .....................XXVII<br />

V.1. MATERIALE ŞI METODE ..................................................................................XXVII<br />

V.2. REZULTATE ŞI DISCUŢII..................................................................................XXVII<br />

V.3. CONCLUZII.........................................................................................................XXVIII<br />

CONCLUZII GENERALE ................................................................................................ XXIX<br />

BIBLIOGRAFIE SELECTIVĂ ......................................................................................... XXXI<br />

PUBLICAŢII PE DURATA STAGIULUI DOCTORAL SI PARTICIPARI LA<br />

SIMPOZIOANE ŞI CONFERINŢE NATIONALE ŞI INTERNAŢIONALE............... XXXIV<br />

II

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

I. INTRODUCERE. SCOP ŞI OBIECTIVE<br />

BIOÎNCAPSULAREA reprezintă o tehnologie nouă, bazată pe inserţia şi imobilizarea<br />

moleculelor bioactive, în ‘’suporturi’’ specifice (matrici). Tehnologia încapsulării este bine<br />

dezvoltată şi utilizată în industria farmaceutică, chimică, cosmetică, alimentară precum şi în<br />

cea tipografică (Augustin et al., 2001; Heinzen, 2002). Potenţialul bioîncapsulării s-a<br />

concretizat tot mai mult în domeniile biotehnologiei, mai ales în cele agricole şi alimentare. În<br />

ultimele decenii, încapsularea compuşilor activi a devenit o tehnologie de mare interes şi<br />

însemnătate, fiind adecvată atât pentru ingredienţii alimentari cât şi pentru cei chimici,<br />

farmaceutici sau cosmetici.<br />

Aplicarea acestei metode de success, de bioîncapsulare a compuşilor bioactivi extraşi<br />

din uleiuri vegetale ar putea permite stabilirea combinaţilor şi a calitaţilor optime ale acestor<br />

substanţe. Este de luat în considerare că o asemenea metodă şi anume bioîncapsularea,<br />

aplicată în aria comercială, ar avea beneficii semnificative pentru industria farmaceutică,<br />

alimentară şi cosmetică. În afară de aceasta este de consemnat faptul că, cercetarea şi<br />

dezvoltarea în aceste domenii este semnificativă mai ales în ceea ce priveşte conservarea<br />

compuşilor naturali bioactivi extraşi din plante.<br />

Scopul acestei tezei constă în utilizarea diferitelor matrici naturale pentru<br />

bioîncapsularea moleculelor bioactive prin metoda gelării ionice (‘’ionotropically crosslinked<br />

gelation’’), precum şi în evaluarea diferenţelor de calitate şi a eficienţei parametrilor pentru<br />

produşii încapsulaţi şi nu în ultimul rând a eliberării controlate a moleculelor bioactive din<br />

matrici.<br />

Structura tezei. Prima parte a acestei teze este reprezentată de un studiu de literatură, partea a<br />

doua include rezultatele experimentale: materiale şi metode, rezultate şi discuţii, concluzii.<br />

Prima parte (Studiul de literatură) este compusă din patru capitole (I-IV):<br />

Capitolul I. Bioîncapsularea: definiţie, principii, aplicaţii, metode şi tehnici<br />

Capitolul II. Uleiuri vegetale funcţionale: caracterizarea fizică, chimică şi autentificarea<br />

Capitolul III: Încapsularea uleiurilor: matrici, metode şi tehnici de încapsulare, evaluarea<br />

eficienţei şi a stabilităţii<br />

Capitolul IV. Metode pentru caracterizarea capsulelor<br />

Partea a doua a tezei (Contribuţiile proprii) include patru capitole, dupa cum urmează:<br />

Capitolul V. Caracterizarea uleiurilor funcţionale utilizate pentru bioîncapsulare.<br />

Această parte caracterizează patru uleiuri funcţionale (ulei de cânepa, ulei de dovleac, ulei<br />

extra virgin de măsline şi ulei de cătină) analizate şi apoi încapsulate prin diferite tehnici:<br />

spectroscopie de absorbţie în ultraviolet (UV), cromatografie de gaze (GC) cu detecţie prin<br />

ionizare în flacără (FID) şi spectroscopie în infraroşu cu transformantă fourier echipată cu<br />

reflectanţă atenuată orizontală (FTIR-ATR), determinările chimice fiind realizate în<br />

conformitate cu metodele descrise în A.O.A.C. şi IOOC.<br />

III

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Capitolul VI. Optimizarea protocoalelor de obţinere a caspsulelor utilizând matrici<br />

naturale şi caracterizarea capsulelor ce conţin ulei încapsulat. Acest capitol descrie<br />

protocoalele pentru: sinteza capsulelor goale de diferite mărimi şi concentraţii, sinteza<br />

capsulelor de diferite mărimi şi concentraţii ce încorporează ulei, caracterizarea capsulelor<br />

goale şi a celor ce conţin uleiuri (în funcţie de mărime şi morfologie), cuprinzând de<br />

asemenea şi analiza FTIR-ATR şi termică a capsulelor.<br />

Capitolul VII. Studierea eficienţei încapsulării şi a eliberării uleiurilor încapsulate. Acest<br />

capitol conţine studii cu privire la eficienţa încapsulării uleiurilor funcţionale în diferite<br />

matrici, determinarea ratei de eliberare a uleiurilor din capsule în timp şi în diferiţi solvenţi,<br />

precum şi eliberarea in vitro a uleiurilor din capsule.<br />

Capitolul VII. Caracterizarea FTIR-ATR a oxidării uleiurilor. Acest capitol include<br />

analize comparative a uleiurilor libere şi încapsulate supuse oxidării în timp în condiţii UV.<br />

Planul experimental se bazeaza pe urmatoarele obiective:<br />

Utilizarea diferitelor matrici naturale (precum alginatul, alginatul în complex cu k-<br />

caragenan şi gume: xantan şi guar, şi chitosan) în scopul încapsulării uleiurilor<br />

funcţionale (ulei de dovleac, ulei extra virgin de măsline, ulei de cânepă şi ulei de<br />

cătină)<br />

Îmbunătăţirea şi optimizarea metodelor de bioîncapsulare pentru uleiurile vegetale cu<br />

proprietăţi funcţionale<br />

Investigarea morfologiei diferitelor capsule obţinute (microscopie electronică de<br />

scanare), caracterizarea capsulelor (suprafaţă, diametru, perimetru, elongaţie,<br />

sfericitate şi compactitate), analize FTIR<br />

Investigarea uleiurilor funcţionale bioîncapsulate: eficienţa şi stabilitatea încapsulării,<br />

eliberarea controlată a uleiurilor încapsulate, materialul şi funcţionalitatea capsulelor<br />

obţinute, caracterizarea FTIR a uleiurilor libere, a capsulelor obţinute şi oxidarea<br />

uleiurilor libere şi încapsulate.<br />

Cercetările prezentate au fost efectuate la Departamentul de Chimie şi Biochimie din<br />

cadrul Universităţii de Ştiinţe Agricole şi Medicină Veterinară, <strong>Cluj</strong>-<strong>Napoca</strong>, în colaborare cu<br />

Universitatea Tehnică Berlin (TU Berlin), Germania, Departamentul de Tehnologie a<br />

Enzimelor, sub supravegherea Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Marion Ansorge-Schumacher. Aş dori de<br />

asemenea să mulţumesc în mod special sponsorilor (Deutsche Bündestiftung Umwelt (DBU)<br />

Germany şi EU COST 865) ce au facut aceste cercetări posibile, acordându-mi cele două<br />

burse pentru studiile doctorale.<br />

IV

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

INTRODUCERE<br />

Microîncapsularea este procesul de producere a capsulelor la o scară micrometrică sau<br />

milimetrică, fiind cunoscute sub numele de capsule.<br />

Bioîncapsularea beneficiază de principiile fundamentale ale încapsulării şi implică<br />

învelirea efectivă a unei forme vii într-o membrană care este inertă, non-toxică pentru celulă,<br />

şi stabilă la condiţiile interioare ale reacţiilor biochimice precum agitarea (Muralidhar R.V. et<br />

al., 2001).<br />

Microcapsula este o capsulă mică, iar procedura de preparare a acesteia este numită<br />

microîncapsulare. Aceasta poate încorpora diferite tipuri de forme materiale pentru a<br />

suplimeta funcţiile secundare şi/sau pentru a compensa în diferite condiţii de mediu.<br />

Microcapsulele pot fi clasificate în trei categorii de bază în funcţie de morfologia<br />

acestora: mononuleare, polinucleare sau de tip matrice.<br />

Microcapsulele mononucleare conţin membrana care protejează compusul bioactiv; în<br />

Fig.1. sunt prezentate câteva tipuri de capsule.<br />

Fig. 1. Diferite tipuri de capsule utilizate (Birnbaum D.T. şi Brannon-Peppas L., 2003)<br />

Capsulele polinucleare prezintă mai mulţi compuşi bioactivi încorporaţi în interiorul<br />

unei membrane. Încapsularea de tip matrice conţine cmpusul bioactiv distribuit omogen pe<br />

toată suprafaţa interioară.<br />

Scopul microîncapsulării<br />

În general există numeroase motive pentru care substanţele ar trebui încapsulate (Li S.P. şi<br />

col., 1988; Finch C.A., 1985; Arshady, R., 1993):<br />

• Creştera stabilităţii pentru protejarea compuşilor activi de mediul extern<br />

• Pentru convertirea componenţilor lichizi activi într-un sistem solid uscat<br />

• Pentru separarea componenţilor incompatibili din punct de vedere funcţional<br />

• Pentru a masca proprietăţile nedorite a componenţilor activi<br />

• Pentru a proteja mediul extern al microcapsulelor de componenţi activi<br />

• Pentru a controla eliberarea compuşilr activi de procesel de eliberare întârziată sau<br />

eliberarea susţinută<br />

• Separarea omponenţilor incompatibili<br />

V

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

• Conversia lichidelor în solide<br />

• Mascarea mirosului, activităţii, etc.<br />

• În scop farmaceutic<br />

Tehnologia de încapsulare este foarte bine dezvoltată fiind acceptată în multe industrii<br />

precum: farmaceutică, chimică, cosmetică, alimentară (Augustin et al., 2001; Heinzen, 2002).<br />

În industria alimetară, grăsimile şi uleiurile, compuşii aromatizanţi şi oleorezinele,<br />

vitaminele, mineralele, coloranţii şi enzimele au fost deja încapsulate (Dziezak, 1988; Jackson<br />

şi Lee, 1991; Shahidi şi Han, 1993).<br />

Alegerea unei tehnici adecvate de bioîncapsulare depinde de utilizarea finală a<br />

produsului şi de condiţiile de procesare implicate în obţinerea produsului final.<br />

Bioîncapsularea îşi găseşte aplicaţie din ce mai multă aplicabilitate în domeniul<br />

biotehnologiilor şi în special în alimentaţie şi agricultură. În ultimele decenii, încapsularea<br />

compuşilor activi a devenit un process de mare interes şi însemnătate, fiind adecvat atât<br />

pentru ingredienţii alimentari cât şi pentru cei chimici, farmaceutici sau cosmetici.<br />

Pfutze S. (2003) consideră că tehnologiile de încapsulare pot fi divizate în două<br />

categorii:<br />

• formarea matricea capsulelor: un ingredient activ şi protector formează granule<br />

omogene. Produsul activ este uniform distribuit în granulă fiind înconjurat din<br />

abundenţă de material protector, formând matricea activă.<br />

• formarea învelişului capsulelor: materialul activ este granulat şi acoperit de un strat<br />

protector. Materialul activ şi protector este bine separat.<br />

Obiectivul principal este construirea unei bariere între particulele componente şi<br />

mediu. Această barieră reprezintă o protecţie împotriva oxigenului, apei, luminei; evitarea<br />

contactului cu alte particule sau ingrediente; sau controlul eliberării lor în timp. Protecţia<br />

compuşilor bioactivi pe parcursul procesării şi păstrării, precum şi eliberarea controlată în<br />

tractusul gastrointestinal este o prioritate în exploatarea potenţialului benefic al multor<br />

compuşi bioactivi.<br />

Tehnicile utilizate la bioîncapsulare necesită un material drept înveliş şi o substanţă<br />

protejată. Materialul utilizat trebuie aprobat de Administraţia Alimentaţiei şi Farmacie (US)<br />

sau de Autoritatea Europeană pentru Securitatea Alimentelor (Europa) (Amrita şi col., 1999).<br />

Coacervarea: încapsularea lichidelor<br />

Coacervarea complexelor (sau faza de separare), este prima aplicaţie la scară largă a<br />

tehnologiei de microîncapsulare. Coacervarea este un proces care are loc în soluţii coloidale şi<br />

de multe ori privită ca metoda originală de încapsulare (Risch, 1995).<br />

Aplicabilitate coacervării complexelor este enormă dar are şi limite datorită costurilor<br />

ei ridicate, în unele aplicaţii. Aceasta include încapsularea:<br />

aromelor<br />

vitaminelor<br />

cristaleor lichide pentru dispozitivele de display<br />

sisteme de imprimare<br />

VI

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

ingredienţi activi pentru industria farmaceutică<br />

bacteri şi celule<br />

Matricile – materiale pentru încapsulare<br />

Există diferite materiale ce pot fi utilizate pentru încapsulare precum: polielectroliţi<br />

sintetici (Sukhorukov şi col., 1998; Donath şi col., 1998), polielectroliţi naturali (Shenoy şi<br />

col., 2003), nanoparticule anorganice (Caruso şi col., 2001), grăsimi (Moya şi col., 2000),<br />

coloranţi (Dai şi col., 2001), ioni polivalenţi (Radtchenk şi col., 2005), şi biomacromolecule<br />

(Yang şi col., 2006).<br />

În general trei clase de materiale au fost utilizate: materiale naturale derivate (colaen ş<br />

alginat), matrici tisulare acelulare (submucoase intestinale) şi polimeri sintetici (acid<br />

poliglicolic, etc.). Aceste clase de biomateriale au foste testate în concordanţă cu<br />

biocomapatibilitatea lor (Pariente şi col., 2002).<br />

Biopolimerii sunt polimeri care provin din surse naturale, sunt biodegradabili, şi<br />

nontoxici. Pot fi produşi de sisteme biologice (ex: microorganisme, plante şi animale), sau<br />

chimic sintetizate din materiale biologice (ex: amidon, grăsimi sau uleiuri, etc.).<br />

Polimeri naturali şi derivaţi ai acestora: polimeri anionici: acid alginic, pectină,<br />

caragenan; polimeri cationici:chitosan, polilizină; polimeri amfipatici: colagen (and gelatină),<br />

chitină; polimeri neutri: dextran, agaroză, pululan.<br />

Guma guar (E412, numită şi guaran) este extrasă din seminţele leguminoaselor din<br />

familia Cyamopsis tetragonoloba. Guma guar prezintă vâscozitate scăzute dar este un bun<br />

agent de întărire. Fiind un polimer non-ionic, nu este influenţat de pH, dar este influenţat de<br />

temperaturi extreme la anumite pH-uri (ex: pH=3 la 50°C).<br />

Alginatul (E400-E404) este produs extras din algele brune (Phaeophyceae, în special<br />

Laminaria). Proprietăţile de gelifiere depind de interacţia cu unii ioni (Mg 2+

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Uleiul de măsline conţine trigliceroli şi cantităţi mici de acizi graşi liberi, glicerol,<br />

pigmenţi, compuşi aromatizanţi, steroli, tocoferoli, fenoli, componenţi răşinoşi neidentificaţi,<br />

etc.(Kiritsakis A., 1998).<br />

Uleiul de dovleac este foarte sănătos, de caliate superioară, fiind în clasamentul<br />

primelor 3 uleiuri nutritive. Seminţele de dovleac au un gust intens şi sunt bogate în acizi<br />

graşi polinesaturaţi. Uleiul brun are un gust amărui. Conţinutul în tocoferoli ai uleiurilor<br />

oscilează de la 27,1 la 75,1 μg/g de ulei pentru α-tocoferol, de la 74.9 la 492.8 μg/g pentru γtocoferol,<br />

şi de la 35.3 la 1109.7 μg/g pentru δ-tocopherol (Stevenson şi col., 2007)<br />

Uleiurile de cătină conţin o cantitate ridicată de acizi esenţiali, linoleic şi alfa linoleic<br />

(Chen şi col., 1990), care sunt precursori ai altor acizi graşi polinesaturaţi cum ar fi acidul<br />

arahidonic sau eicosapentanoic. Este stocat în organitele extracitoplasmatice numite vezicule<br />

de ulei, o formă naturală de încapsulare (Socaciu et all, 2007, 2008). Uleiul din pulpa frutelor<br />

de cătină este bogat în acid palmitoleic şi acid oleic (Chen şi col., 1990).<br />

Uleiurile conţin de asemenea flavonoizi (Chen şi col., 1991), carotenoizi, steroli liberi<br />

şi esterificaţi, triterfenoli şi izoprenoli (Goncharova şi Glushenkova, 1996). Conţinutul în<br />

carotenoizii variază de asemenea în funcţie de sursa de provenienţă a uleiului.<br />

Proprietăţile fizice şi chimice ale uleiurilor funcţionale<br />

Proprietăţile fizice şi chimice ale uleiurilor, incluzând indicele de iod, de saponificare<br />

şi valorile de aciditate şi pentru peroxizi, indicele de refracţie, densitate şi materia<br />

nesaponificabilă sunt determinate conform procedurilor standard. Indicele de iod măsoară<br />

gradul de nesaturare al uleiurilor. Valoarea acestuia sub 100 demonstrază că uleiul prezintă un<br />

grad redus de saturare (Pa Quart, 1979; Pearson, 1981). Indicele de saponificare este un<br />

indicator al mediei masei moleculare a acizilor graşi prezenţi în ulei (AOAC, 1980; Pearson,<br />

1981). Indicele de peroxid este frecvent utilizat pentru măsurarea stadiului de oxidare al<br />

uleiului. Acesta indică oscilarea oxidativă a uleiului (deMan, 1992).<br />

Tehnicile pentru caracterizarea şi autentificarea uleiurilor funcţionale<br />

Există diferite tehnici pentru caracterizarea şi autentificare produselor alimetare.<br />

Metodele de autentificare aplicate pentru uleiuri şi grăsimi pot fi clasificate ca şi chimice (de<br />

separative) sau fizice (non-separative).<br />

Spectrometrele de infraroşu cu transformantă fourier (FTIR) prezintă multe avantaje în<br />

comparaţie cu instrumentele convenţionale de dispersie, printr-o excelentă reproductibilitate<br />

şi acurateţe a lungimilor de undă, precisa manipulare spectrală şi utilizarea unor programe<br />

chemometrice pentru calibrare. Accesoriile HATR au fost de asemenea larg utilizate în<br />

dezvoltarea metodelor FTIR pentru analizarea uleiurilor şi a grăsimilor, deoarece acestea pot<br />

oferi mijloace convenable şi simple pentru o manipulare uşoară (Sedman şi col., 1999).<br />

Spectroscopia infraroşu de mijloc (MIR) poate fi utilizată pentru identificarea compuşilor<br />

organici deoarece unele grupe de atomi prezintă proprietăţi ale frecvenţei de absorbţie a<br />

vibraţiilor în regiunea infraroşie a spectrului electromagnetic. Reflectanţa orizontală totală<br />

atenuată (HATR) este accesoriul cel mai des utilizat in metoda FTIR pentru analizele<br />

uleiurilor şi a grăsimilor (Sedman şi col., 1999).<br />

VIII

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

O largă varietate de alimente utilizează pentru încapsulare aromatizanţi, acizi, baze,<br />

îndulcitori artificiali, coloranţi, antioxidanţi, agenţi cu arome nedorite, mirosuri, etc. Aceştia<br />

îşi păstreză bioactivitatea şi rămân accesibili agenţilor externi.<br />

Fitosterolii, flavonoizii şi compusii organici cu sulf, reprezintă trei grupe de compuşi<br />

caracteristici fructelor şi legumelor, care ar putea prezenta importanţă în reducerea riscului de<br />

ateroscleorză. (Howard şi Kritchevsky, 1997). Unele substanţe fitochimice, cu ar fi acidul<br />

ascorbic, carotenoizii, vitamina E, fitofenoli, izoflavoni şi fitosteroli, au fost evidenţiate ca<br />

ingredienţi fiziologic activi ce îmbunătăţesc rezistenţa la anumite boli.<br />

Încapsularea poate fi utilizată pentru condiţionarea uleiurilor în forme solide sau<br />

solubile în apă, extinzând utilizarea lor în multe alte aplicaţii. Încapsularea uleiurilor include<br />

ca metode şi tehnici: spray-drying, spray-chilling, fluid bed encapsulation, extrusion<br />

encapsulation şi încapsularea prin coacervare.<br />

Extrudarea este utilizată pentru încapsularea mineralelor şi vitaminelor în uleiuri<br />

(grăsimi saturate) într-o matrice de tip polizaharidic (Van Lengerich şi Lakis, 2002). Protecţia<br />

împotriva oxidării metil-linoleatului încapsulat cu gumă acacia prin metoda spray drying şi<br />

freeze drying, depinde de umiditatea relativă a mediului (Minemoto şi col., 1997).<br />

În majoritatea cazurilor matricile utilizate pentru încapsularea uleiurilor şi grăsimilor<br />

sunt gume (acacia, arabică), proteine, carbohidraţi (cazeină/zaharuri), maltodextrină, betaciclodextrine,<br />

alginat de sodiu, gelatină.<br />

PARTEA II. CONTRIBUŢII PROPRII (ORIGINALE)<br />

CAPITOL II. CARACTERIZAREA ULEIURILOR FUNCŢIONALE UTILIZATE LA<br />

BIOÎNCAPSULARE<br />

Uleiurile extrase din plante (floarea-soarelui, dovleac, soia, rapita, etc.) sunt foarte<br />

utilizate in domeniul alimentar, dar si in alte industrii (cosmetică, farmaceutică, etc.).<br />

PrezintĂ o deosebita insemnatate datorita numerosilor componenţi benefici care intră în<br />

alcătuirea lor. Calitatea şi autenticitatea acestor uleiuri se realizează prin diferite tehnici. Cele<br />

mai utilizate trei tehnici în vederea caracterizării acestor uleiuri sunt: spectrometriA UV-Vis,<br />

cromatografia gaz cu detecţie prin ionizare în flacără FID, şi spectroscopia infraroşu cu<br />

transformantă fourier (FTIR).<br />

II.1. MATERIALE ŞI METODE<br />

Au fost alese în vederea încapsulării patru uleiuri de mare interes: cătină (SBO) extras<br />

din fructele de catina, colectate din regiunea <strong>Cluj</strong>ului (Transilvania, nordul Romaniei), ulei de<br />

măsline extra virgin (EVO) din Italia, cânepă (HP) şi dovleac (PK) din Romania.<br />

Analizele chimice au fost determinate conform metodelor descrise de: A. O. A. C. şi<br />

IOOC sau de Comisia Uniunii Europene (EU): aciditatea şi indicele de iod. Toate probele au<br />

fost analizate în triplicat. Aciditatea a fost calculată luându-se în considerare conţinutul de<br />

IX

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

acizi graşi liberi ale uleiurilor analizate, determinat prin titrare conform metodei oficiale Ca<br />

5a-40. Indicele de iod a fost determinat prin metoda AOCS Cd 1c-85 (1997).<br />

II.2. REZULTATE ŞI DISCUŢII<br />

Determinarea acidităţii şi a indicelui de iod<br />

Rezultatele analizelor chimice prezentate în Tabelul II.1. au demonstrat o bună<br />

corelaţie a valorilor obţinute cu cele publicate în literatură.<br />

Tabel II.1. Caracteristicile chimice şi fizice ale uleiurilor analizate în comparaţie cu literatura<br />

Aciditate<br />

(mg KOH/g ulei)<br />

Ulei de Cânepa Ulei de măsline<br />

extra virgin<br />

Caracteristicile fizice si chimice<br />

Ulei de dovleac Ulei de cătină<br />

1.93 / 4.0* 2.64 / 6.6* 1.32 / 4.0* 3.7 / 4.0*<br />

Indicele de iod** 162 / 145-166* 87 / 75-95* 130 / 116-133* 71 / 98-119*<br />

**Indicele de Iod a fost calculat cu metoda AOCS Cd 1c-8<br />

* Date din literatura<br />

Aceste date demonstrează faptul că valorile acestor uleiuri corespund cu indicii de<br />

calitate ai iodului din Codex, excepţie uleiul de cătină, a cărui valori în cazul acidităţii nu<br />

corespund intervalelor acidităţii precizate în literatură.<br />

Determinarea amprentei uleiurilor prin spectrometrie ultra violet/visibil (UV-Vis)<br />

Caracterizarea spectrală (fingerprintul) specifică fiecărui ulei analizat prin UV-Vis<br />

este prezentat in Fig. I.1. Diferenţele dintre un ulei autentic si un ulei falsificat a fost<br />

demonstrate prin poziţia şi absorbanţa peakurilor caracteristice fiecărui ulei (Socaciu C. et al.,<br />

2005).<br />

Ulei de cânepă (Cannabis sativa L)<br />

Amprenta spectrală UV-Vis caracteristică uleiului de cânepă în conformitate cu datele<br />

precizate de OMLC, este dat de conţinutul ridicat în pigmenţi clorofilici, având absorbanţa<br />

maximă la 411 nm (Fig.II.1.A.).<br />

X

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

A. B<br />

C. D.<br />

Fig.II.1. Spectrele UV-Vis ale uleiurilor analizate (amprenta specifică în regiunea 350-600 nm<br />

continând detalii referitoare la maximul absorbantei peakului specific: A. Ulei de cânepă; B.<br />

Ulei de măsline extra virgin (EVO); C. Ulei de dovleac (PK); D. Ulei de cătină (SB)<br />

Ulei de măsline extra virgin (Olea europaea )<br />

Culoarea caracteristică uleiului de măsline depinde de majoritatea pigmenţilor<br />

conţinuţi, în principiu acest ulei având un conţinut ridicat în carotenoide şi clorofile. Uleiul<br />

provenit din măslinele ajunse la maturitate prezintă o culoare galbenă datorită continutului în<br />

pigmenţi carotenoidici galbeni. În general culoarea acestui ulei variază şi este datorată<br />

combinaţiei şi diferetelor proporţii de pigmenţi. Exista o simplă ecuaţie: Culoarea= clorofilă<br />

(verde) + carotenoide (galben) + alţi pigmenţi.<br />

Conţinutul în pigmenţi clorofilici se diminueaza odată cu atingerea maturităţii<br />

fructelor. Fingărprintul specific uleiului de măsline analizat este atribuit ‘’ecuaţiei culorii’’<br />

menţionată anterior (Fig.II.1.D.).<br />

Ulei de dovleac (Cucurbita pepo)<br />

Amprenta spectrală (fingerprintul) a acestui ulei este acceptat ca avand doua umere,<br />

unul la 418 nm cu absorbanţă mai mică, şi unul la 435 nm cu absorbanţă mai mare<br />

XI

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

(Fig.II.1.C.), în cazul falsificării sau oxidării, acest ulei prezintă absorbanţele celor două<br />

umere schimbate (Lankmayr şi col., 2004).<br />

Uleiul de cătină (Hippophae rhamnoides)<br />

Spectrului acestui ulei demonstrează ca fingărprintul este dat de cele trei umere care<br />

dau spectrul, care sunt caracteristice carotenoidelor, mai exact beta-carotenului, intre 400 şi<br />

500 nm (Fig.II.1.A.), acesta fiind compusul principal al acestui ulei (Lichtenthaler şi<br />

Buschmann, 2001).<br />

Analiza uleiurilor prin spectroscopia infrarosu cu furie transformata (FTIR)<br />

Studiile FTIR ale uleiurilor analizate au demonstrate existenta relatiei intre fecventele<br />

si absorbantele benzilor specifice si compozitia acestora. Aceste frecvenţe şi valoarea<br />

absorbanţei lor, au fost utilizate în continuare pentru evaluarea oxidarii uleiurilor (Guillen, M.<br />

D. şi Cabo, N, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2002).<br />

În conformitate cu aceste spectre au fost identificate principalele benzi şi frecvente în<br />

domeniul infraroşu ale uleiurilor analizate ( Tabel II.2.).<br />

Nr.<br />

banda<br />

HP<br />

(cm -1 )<br />

EOV<br />

(cm -1 )<br />

Tabel.II.2. Benzile infraroşu relevante ale uleiurilor investigate<br />

PK<br />

(cm -1 )<br />

SB<br />

(cm -1 )<br />

Grupul functional Modul de vibratie<br />

1 3008 3005 3008 3006 =C-H (cis-) de întindere<br />

2 2956 2956 2956 2956 -C-H (CH3) de întindere (asimetrică)<br />

3 2923 2923 2923 2922 -C-H (CH2) de întindere (asimetrică)<br />

4 2853 2853 2854 2853 -C-H (CH2) de întindere (asimetrică)<br />

5 1742 1742 1742 1742 -C=O (ester) de întindere<br />

6 1654 1653 1653 1653 -C=C- (cis-) de întindere<br />

7 1463 1464 1464 1464 -C-H (CH2, CH3)<br />

8 1456 1456 1456<br />

9 1418 1417 1418 1417 =C-H (cis-) de deformare<br />

10 1396 1402 1398 1402 de deformare<br />

11 1377 1377 1377 1377 -C-H (CH3) de deformare (simetrică)<br />

12 1317 1319 de deformare<br />

13 1236 1238 1238 1238 -C-O, -CH2- de întindere, de deformare<br />

XII

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

14 1155 1159 1157 1161 -C-O, -CH2- de întindere, de deformare<br />

15 1120 1118 1120 1116 -C-O de întindere<br />

16 1097 1097 1099 1095 -C-O de întindere<br />

17 1028 1028 1029 1033 -C-O de întindere<br />

18 958 962 968 -HC=CH- (trans-) de deformare înafara<br />

planului<br />

19 914 914 -HC=CH- (cis-) de deformare înafara<br />

planului<br />

20 721 721 721 721 -(CH2)n-, -HC=CH-<br />

(cis-)<br />

de deformare ( rocking)<br />

Spectrele uleiurilor analizate par a fi in principiu similare, însă diferenţele în<br />

intensitatea benzilor ca de altfel şi a frecvenţelor fac posibilă diferenţierea foarte clară a<br />

compoziţiei acestor uleiuri (see Fig. II.2.).<br />

Fig.II.2. Spectrul FTIR-ATR al zonei de fingerprint (1700-800 cm -1 ) a uleiurilor analizate<br />

HP= cânepă, EVO (EOV) = măsline extra virgin; PK= dovleac; SB= cătină<br />

XIII

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Profilul acizilor graşi prin cromatografia gaz<br />

Compoziţia acizilor grasi analizaţi prin GC-FID in acest studio sunt evidentiati in<br />

Tabelul II.3. Profilul acizilor graşi a fost comparat cu al uleiurilor din literature.<br />

Acizi grasi %<br />

Tabel.II.3. Compoziţia procentuală a acilor graşi din uleiurile analizate<br />

Ulei de Canepa Ulei de masline<br />

extra virgin<br />

Ulei de dovleac Ulei de catină<br />

Palmitic (16:0) 7.48 7.28 6.29 7.76<br />

Stearic (18:0) 1.66 2.67 3.64 0.3<br />

Arachidic (20:0) 1.06 - - 0.11<br />

Σ saturati % 10.02 9.95 9.93 8.17<br />

Palmitoleic<br />

(C16:1)<br />

Oleic<br />

(C18:1)<br />

Linoleic<br />

(C18:2)<br />

Linolenic<br />

(18:3n3)<br />

Eicosadienoic<br />

(C20:2)<br />

-<br />

14.94<br />

72.6<br />

-<br />

0.55<br />

-<br />

36.81<br />

43.14<br />

0.93<br />

-<br />

-<br />

42.44<br />

46.71<br />

Σ nesaturati % 87.54 80.88 90.07 12.5<br />

C18:1/C18:2 0.21 0.85 0.91 6.3<br />

omega 3 : omega<br />

6 acizi grasi<br />

II.3. CONCLUZII<br />

0.92<br />

- 0.022 0.02 -<br />

Prin GC-FID, s-a determinat compoziţia în acizi graşi a uleiurilor analizate şi s-a facut<br />

comparaţia cu datele din literatură. În urma acestei analize s-au concluzionat urmatoarele:<br />

• compoziţia uleiului de cânepă nu corespunde cu valorile precizate în literatură pentru<br />

acizii graşi, acesta avand un conţinut mai scăzut. Acidul oleic se incadrează in<br />

intervalul prevăzut in literatură<br />

• principalii acizi graşi în uleiul de măsline extra virgin sunt acidul oleic şi linoleic, şi de<br />

asemenea în cantitate mai mică acidul lonoleic<br />

-<br />

5.4<br />

6.3<br />

-<br />

0.8<br />

-<br />

XIV

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

• în cazul uleiului de dovleac, compoziţia în acizi graşi corespunde cu valorile precizate<br />

în litaratura, excepţie facând acizii palmitic şi stearic care sunt prezenţi in concentrţii<br />

mai mici<br />

• profilul acizilor graşi a uleiului de cătină a demonstrat faptul că acest ulei provine din<br />

pulpa/pielea fructelor şi nu din seminţe, fiind foarte bogat in acidul palmitic şi oleic<br />

CAPITOLUL III. BIOÎNCAPSULAREA ULEIURILOR: PROTOCOALE DE<br />

PREPARE A CAPSULELOR ŞI CARACTERIZAREA LOR<br />

III.1. MATERIALE ŞI METODE<br />

În vederea realizării parţii experimentale din acest capitol s-au utilizat urmatoarele:<br />

• matrici pentru încapsulare: alginat, k-caragenan, chitosan, gumă xantan şi<br />

gumă guar, procurate de la Sigma Aldrich<br />

• solvenţii si reactanţii necesari de asemenea de la Sigma Aldrich<br />

• uleiurile utilizate la încapsulare au fost prezentate in capitolul anterior<br />

Protocol pentru sintetizarea capsulelor goale de diferite mărimi şi concentraţii<br />

Diferite concentratii de alginat (1%, 1.5%, 2% w/v), amestec de: alginat si caragenan,<br />

alginat si guma xantha, alginat si guma guar au fost dizolvate in apa deionizata pentru ~ 30<br />

minute. Diferite concentratii de chitosan (1%, 1.5%, 2% w/v) au fost dizolvate 0.7% v/v acid<br />

acetic glacial.<br />

Alginatul şi amestecul de alginat au fost pipetate într-o solutie de 2% CaCl2 în apa (ca şi<br />

baie de întărire), utilizând o pompa peristaltica cu un injector de 0.4 x 20mm, iar capsulele au<br />

fost formate instantaneu.<br />

Chitosanul a fost pipetat in 5% (w/v) solutie de NaTPP in apa (ca si baie de intarire),<br />

utilizând pipeta pentru control.<br />

Dupa ~ 1h, capsulele au fost separate din baia de intarire şi transferate în placi “Petri”<br />

pentru protecţie si conservare.<br />

Protocol pentru sintetizarea capsulelor de diferite mărimi şi concentraţii cu uleiri<br />

încorporate<br />

S-au luat în considerare doar concentraţiile de matrici care au prezentat emulsiile cele mai<br />

stabile. De asemenea vâscozitatea soluţiilor a fost considerat un factor principal în vederea<br />

alegerii concentraţiilor de matrici. Protocolul pentru obţinerea capsulelor a fost descris<br />

anterior.<br />

XV

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Evaluarea microscopica a emulsiilor înaintea încapsulării<br />

Evaluarea microscopică a emulsiilor înaintea încapsulării a fost determinată utilizând<br />

un microscop Olimpus optical microscope BX51M, echipat cu camera digitală.<br />

Caracterizarea capsulelor: dimensiuni şi morfologie, analize FTIR şi termice<br />

Parametri luaţi in considerare în vederea caracterizării capsulelor, precum dimensiune,<br />

arie, perimetru, elongaţie si compactitate, au fost determinaţi utilizând UTHSCSA ImageTool<br />

ca şi software.<br />

Morfologia suprafeţei capsulelor a fost determinată utilizându-se microspia electronică<br />

scanată (Hitachi S-2700, iMOXS, cu detector BSE). Capsulele analizate au fost suflate şi<br />

învelite în aur înaintea supunerii analizelor microscopice.<br />

III.2. REZULTATE ŞI DISCUŢII<br />

Evaluarea microscopica a emulsiilor înaintea încapsulării<br />

Stabilitatea emulsiilor este un factor cheie în evaluarea în condiţii de temperatura în<br />

vederea păstrării timp mai îndelungat a produselor pe baze de emulsii.<br />

Mărimea picăturilor de ulei dispersate in structura matricilor dizolvate care au fost<br />

comparate in vederea evaluarii stabilitatii emulsiilor obtinute. Emuliile cu cea mai bună<br />

stabilitate în timp au fost utilizate mai departe pentru încapsulare. Mărimea picăturilor de<br />

uleiuri au fost dispersate uniform in matrici, în funcţie de stabilitatea matricei, uniformitatea<br />

crescând odată creşterea concentraţiei matricilor (Fig.III.1.).<br />

Caracterizarea capsulelor<br />

Dupa obtinerea emulsiilor, si pipetarea lor in baile de intarire, datorita interactiilor cu<br />

ionii de legare in vederea formarii gelurilor.<br />

Capsulele continand uleiuri au avut o forma aproximativ sferica, culoare variind intre<br />

alb-galbui si portocaliu.<br />

Luându-se in considerare toate caracteristicile capsulelor obtinute, si facand o<br />

comparatie intre aceste caracteristici ale capsulelor goale şi a celor continand uleiuri, s-a<br />

constatat ca incorporarea uleiurilor în capsule modifica aceste caracteristici (Fig.III.2.).<br />

Compararea capsulelor între ele continand uleiuri, a demonstrat ca sfericitatea şi<br />

compactitatea nu au fost prea mult afectate de incorporarea uleiurilor. Insa in cazul<br />

diametrului, ariei, elongatia, au fost clar determinate diferente foarte mari.<br />

XVI

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

A. B.<br />

C. D.<br />

Fig. III.1. Imagini microscopice ale diferitelor emulsii: A. alginat 2%; B. alginat 1%; C. complex alginat-gumă<br />

guar; D. complex alginat-gumă xantan. Scala reprezintă 5 μm.<br />

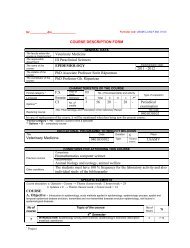

Parameter values/Valoarea parametrilor<br />

9<br />

8<br />

7<br />

6<br />

5<br />

4<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

0<br />

AG-CAR (0.5:0.5)<br />

AG-XG (0.75:0.75)<br />

AG-CAR (0.75:0.75)<br />

AG-XG (0.5:0.5)<br />

AG-GG (0.75:0.75)<br />

AG-GG (0.5:0.5)<br />

Samples/Probele<br />

AGoil2%<br />

AGoil1.5%<br />

AGoil1%<br />

CHoil2%<br />

CHoil1.5%<br />

CHoil1%<br />

Area / Aria (cm2)<br />

Perimeter / Perimetru<br />

Elongation (axes ratio)/<br />

Elongatia (raportul axelor)<br />

Roundness (up to 1) /<br />

Sfericitatea val. max. 1<br />

Diameter / Diametrul (cm)<br />

Compactness (up to 1)/<br />

Compactitatea (val. max. 1)<br />

Fig.III.2. Reprezentarea grafică comparată a caracteristicilor capsulelor din complexul alginat cu k-caragenan,<br />

gume xantan şi guar, alginat şi chitosan continând ulei: AG-CAR (0.5:0.5) = complex alginat-k-carrageenan<br />

(raport 0.5:0.5) continând ulei; : AG-CAR (0.75:0.75) = complex alginat-k-carrageenan (raport 0.75:0.75)<br />

continând ulei; AG-XG (0.75:0.75) = complex alginate-guma xantan (raport 0.75:0.75) continând ulei; AG-XG<br />

(0.5:0.5) = complex alginate-guma xantan (raport 0.5:0.5) continând ulei;AG -GG (0.75:0.75) = complex<br />

alginate-guma guar (raport 0.75:0.75) continând ulei; AG -GG (0.5:0.5) = complex alginate-guma guar (raport<br />

0.5:0.5) continând ulei; AGoil2% = capsule alginat 2% continând ulei; AGoil1.5% = capsule alginat 1.5%<br />

continând ulei; AGoil1% = capsule alginat 1% continând ulei; ; CHoil2% = capsule chitosan 2% continând<br />

ulei; CHoil1.5% = capsule chitosan 1.5% continând ulei; CHoil1% = capsule chitosan 1% continând ulei<br />

XVII

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Microscopia electronică scanată (SEM)<br />

Scopul acestor analize a fost de a evalua si caracteriza topologia capsulelor obtinute<br />

continand uleiuri. Suprafata capsulelor a fost non-regulara, aceasta datorita picaturilor de ulei<br />

prezente, exceptand chitosanul care prezinta o suprafata mult mai mata (Fig.III.3.A).<br />

Fotografiile SEM ale capsulelor nu prezintă porozitate (Fig.III.3.).<br />

A. B.<br />

Fig.III.3. Morfologia suprafetei diferitelor capsule obtinute continand uleiuri utilizand microscopia electronica<br />

de scanare: A. alginat-caragnan complex; B. chitosan. Bara indicand scala este reprezentata in fiecare poza.<br />

Magnificatia 70x.<br />

Analizele FTIR<br />

Caracterizarea FTIR a matricilor<br />

În urma analizelor FTIR-ATR s-a realizat caracterizarea matricilor utilizate la<br />

încapsulare, realizându-se astfel o comparaţie între matrici (AG, CAR, CH, GG, XG).<br />

Principalele frecvenţe caracteristice matricilor în vederea identificării individuale sunt: 3244-<br />

3302 cm -1 (O-H stretch), 1400-1474 cm -1 (CH2 bending), 1000-1200 cm -1 (C-O şi C-C<br />

stretch), 924-1000 cm -1 ( poly OH şi CH2 twist), 776-892 cm -1 (glycoside).<br />

Vibraţiile şi grupurile<br />

funcţionale<br />

O–H intindere 3244 3514<br />

AG CAR GG XG CH<br />

grupul poliOH<br />

3299 3302 3289<br />

O-H +<br />

N-H de<br />

întindere<br />

XVIII

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

C–H întinderea grupului CH2 2926 2953, 2911, 2894 2884 - 2935<br />

C-O de întindere ( COOH) 1597 - 1636 - 1651<br />

deformarea grupării CH2 1408 1474, 1400 1408 1400 1428<br />

O-H deformare - 1223 ( S=O vibraţia<br />

de întindere a sulfet<br />

esterului)<br />

1350 1247 -<br />

C-O şi C-C întindere 1200-1000 - 1145 1150 1151<br />

–CH2OH modul de întindere 1054 1063 1054 1061<br />

Gruparea C–OH alcolică<br />

(C-O întinderea zaharidelor)<br />

–CH2 vibraţie 948, 902,<br />

1024 1024 - 1025 1024<br />

Provenite de la<br />

acizii: guluronic<br />

şi maluronic<br />

924, 910<br />

Grupările<br />

polihidroxi<br />

legaturile glicozidice 809 842<br />

Sulfatul galactozic,<br />

legatura glicozidică<br />

FTIR characterization of different beads containing oils<br />

1016 - -<br />

866,777<br />

(1,4; 1,6) legatura<br />

galactozei şi<br />

manozei<br />

785<br />

C-H de<br />

deformare<br />

C-C întindere<br />

Spectrele matricelor, ale capsulelor goale, capsulelor continand uleiuri au fost<br />

analizate. Concentratia matricelor nu a influentat caracteristicile capsulelor prin FTIR. Un<br />

exemplu concludent este reprezentat in Fig.III.4., spectrele uleiului de cătină (SB) şi ale<br />

capsulelor din alginat 2% conţinand ulei SB.<br />

În urma încapsulării uleiului de SB în capsule de alginate, se produce o creştere a<br />

intensităţii absorbanţei la 3400 cm -1 (care este direct proporţională cu creşterea concentraţiei<br />

de alginate utilizată la încapsulare) precum şi o shiftare a unor peakuri spre valori şi frecvenţe<br />

mai scăzute în regiunea 1000-1500 cm -1 , regiune specifică uleiului de SB<br />

Spectrele amestecului de uleiuri si capsule au demonstrat prezenta peakurilor specifice<br />

uleiurilor in doua zone distuncte (2800-2900 cm -1 şi 1700-900 cm -1 ), confirmându-se astfel<br />

prezenţa uleiurilor în capsule.<br />

892,<br />

776<br />

XIX

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Fig.III.4. Spectru FTIR-ATR înregistrat pentru: A. Capsule de alginat 2% conţinând SB; B. pudră alginat; C.<br />

ulei SB; D. capsule goale de alginat 2%<br />

Analize termice<br />

Analize DSC<br />

Termogramele DSC ale uleiurilor libere si ale diferitelor capsulelor continand uleiuri,<br />

au fost masurate.<br />

Cateva dintre peakurile endotermice, ca si exemplu ale uleiului de catina, si ale unor<br />

capsule continand ulei de catina, sunt prezentate in reprezentarea grafica din Fig.III.5.;<br />

temperature peakurilor cerste direct proportional cu cresterea temperaturii, fiecare peak fiind<br />

characteristic fiecărui tip de capsula obţinută.<br />

Analize termogravimetrice<br />

Termogramele TGA ale uleiurilor libere si ale diferitelor capsulelor continand uleiuri,<br />

au fost masurate.<br />

Cateva rezultate referitoare la pierderea in masa a diferitelor tipuri de capsule<br />

obtinute, este prezentata in graficul din Fig.III.6.. Pierderea în greutate, reprezentata in figura<br />

anterioara, demonstreaza ca aceasta se datoreaza continutului ridicat in apa a unor capsule.<br />

Uleiurile nu influenteaza foarte mult pierderea in greutate, la un ulei liber aceasta fiind de<br />

99.44%. Dar in timpul procesului de oxidare aceste uleiuri pierd din greutate, datorita<br />

reactiilor oxidarii.<br />

XX

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Temperature (°C)<br />

200<br />

180<br />

160<br />

140<br />

120<br />

100<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

AG 2% AG<br />

1.5%<br />

Alginate<br />

1%<br />

AG-CAR<br />

(0.75%)<br />

CH 2% CH 1% AG-GG AG-KG SB<br />

Fig. III.5. Reprezentarea grafica a peakurilor endotermice ale unor tipuri de capsule<br />

DSC si TGA au fost in ultimul timp foarte mult utilizate in monitorizarea stabilitatii, a<br />

comportamentului termic, a parametrilor de cinetica in diferite uleiuri (Jayadas et al., 2006;<br />

Milovanovic et al., 2006; Bahruddin et al., 2008). În acest studiu analizele termice au fost<br />

efectuate pana la temperatura de 300°C. Diferenţele nu foarte mari între probe se datoreaza<br />

tocmai acestei temperature, deoarece conform cu literatura, oxidarea uleiuriloe prin metode<br />

termice se poate determina la expunerea probelor la o temperatura mai mare de 300°C, iar<br />

pierderea in greutate poate fi pana la 10%, aceasta depinzând de natura uleiului (Jayadas et<br />

al., 2006; Milovanovic et al., 2006; Bahruddin et al., 2008).<br />

Restmass %<br />

120<br />

100<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

AG 2% AG 1.5% AG-CAR<br />

(0.75%)<br />

AG-GG AG-KG SB<br />

Fig.III.6. Reprezentarea grafică a pierderii de masă % a probelor analizate TGA<br />

Scopul acestor analize termice a fost acela de a analiza şi a determina stabilitatea<br />

termică a capsulelor obţinute continând diferite uleiuri, în vederea viitoarelor aplicaţii ale<br />

acestora în domeniul alimentar şi cosmetic. În astfel de aplicaţii se cunoaşte necesitatea<br />

XXI

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

sterilizării probelor sau expunerea la presiuni înalte în vederea evitării biohazardului sau<br />

contaminării, aceste tratamente fiind facute în timpul proceselor tehnologice.<br />

III.3. CONCLUZII<br />

Studiile experimentale realizate, cu scopul bioîncapsulării unor uleiuri funcţionale în<br />

matrici naturale, utilizând ca şi metodă ‘’ionotropically crosslinked gelation’’, au demonstrate<br />

posibilitatea utilizării acestei tehnici în vederea bioîncapsulării unor compuşi naturali şi<br />

eliberarea lor condiţionată.<br />

Cele mai bune matrici în vederea bioîncapsulării uleiurilor s-au dovedit a fi: alginatul<br />

şi chitosanul în concentrţii de 2%, 1.5% şi 1%, complexele alginatului cu k-caragenan, şi<br />

gume guar şi xantan în raport de concentraţie 0.75:0.75.<br />

Rezultatele au arătat faptul că bioîncapsularea uleiului a afectat diametrul capsulelor,<br />

acesta crescând direct proporţional cu cantitatea de ulei utilizată pentru încapsulare. De<br />

asemenea şi ceilalţi parametri masuraţi în vederea caracterizării capsulelor au fost influenţaţi<br />

şi de cantitatea de ulei utilizată.<br />

Prin analizele FTIR-ATR, diferitele capsule conţinând uleiuri au prezentat peakuri<br />

care sunt atribuite atat uleiurilor cât şi capsulelor goale (regiunile dintre 2800-2900 cm -1 şi<br />

1700-900 cm -1 ). Astfel se demonstrează prezenţa uleiurilor în capsule, deci încapsularea<br />

acestora.<br />

CAPITOL IV. EFICIENŢA ÎNCAPSULĂRII ŞI STUDII DE ELIBERARE A<br />

ULEIURILOR DIN CAPSULE<br />

IV.1. MATERIALE ŞI METODE<br />

Eficinţa încapsulării e uleiurilor în capsule<br />

Încapsularea uleiurilor a fost determinată calculând cantitatea de beta-caroten sau<br />

cantitatea de carotenoid care este principalul component major al fiecărui ulei analizat înainte<br />

şi după încapsulare. Această determinare a fost realizată spectrofotometric, iar eficinţa<br />

încapsulării (EE%) a fost calculată conform ecuaţiei:<br />

EE% = C1/C2 x 100, C1= concentraţia carotenoid din ulei iniţială<br />

C2= concentraţia carotenoid din ulei după încapsulare<br />

XXII

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Măsurarea ratei de eliberare a uleiurilor din capsule<br />

Eliberarea controlată a uleiurilor din capsule a fost determinata de asemenea<br />

spectrofotometric, utilizând un spectrofotometru CarWin 50 UV-VIS. Măsurătorile au fost<br />

facute în triplicat la temperatura camerei, utilizându-se cuvete de cuarţ de 2 mm.<br />

Eliberarea in vitro a uleiurilor din capsule<br />

Stimularea fluidului gastric a fost realizată conform urmatorul protocol:<br />

• timp de o ora la pH 1.2 intr-o solutie de 0.1N HCl cu⁄si 5 ml Sanzyme (sirop de<br />

enzime continand 80 mg papaina, 40 mg pepsina and 10 mg sanzyme 2000)<br />

• in urmatoarele 2-3 ore capsulele au fost transferate in intr-o solutie in vederea<br />

stimulatii fluidului intestinal pH 4.5 tot asa cu⁄si fara enzyme<br />

• urmatoare ore au fost transferate in solutie stimuland fluidul intestinal la pH 7.4,<br />

aceasta fiind formata din KH2PO4 1.074g in 30 ml de 0.2N NaOH, si pancreatina 275<br />

mg (utilizand “Triferment”)<br />

• toate testările s-au efectuat la 37ºC cu barbotare continuă de CO2<br />

IV.2. REZULATTE ŞI DISCUŢII<br />

Eficinţa încapsulării e uleiurilor în capsule<br />

Eficienţa încapsulării este reprezentata în graficul din Fig.IV.1. pentru diferite tipuri de<br />

capsule. Valorile prezentate sunt ale uleiului de cătină, însa pentru toata uleiurile analizate<br />

aceasta eficienţă a prezentat aceleaşi valori.<br />

După cum se poate observa şi în graficul prezentat, eficienţa încapsulării este direct<br />

proporţionala cu creşterea concentraţiei matricilor. Dintre toate matricile şi complexele de<br />

matrici utilizate, după cum se poate observa şi in graficul din Fig.IV.1., s-a obţinut cea mai<br />

bună eficienţa a încapsulării utilizând ca şi matrici: alginatul în concentraţie de 2%, chitosanul<br />

in aceeaşi concentraţie, urmate de concentraţiile de 1.5%, şi de alginatul în complex cu kcaragenan<br />

şi gume în raport de 0.75:0.75%.<br />

XXIII

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Fig.IV.1. Reprezentarea grafica comparata a eficientei incapsularii a uleiurilor in capsule din complexul alginat<br />

cu k-caragenan, gume xantan si guar, alginat si chitosan : AG2% = capsule alginat 2% ; CH2% = capsule<br />

chitosan 2% ; CH1.5% = capsule chitosan 1.5% ; AG1.5% = capsule alginat 1.5% ; AG-CAR (0.75:0.75) =<br />

complex alginat-k-carrageenan (raport 0.75:0.75) ; AG-XG (0.75:0.75) = complex alginate-guma xantan (raport<br />

0.75:0.75); CH1% = capsule chitosan 1%; AG -GG (0.75:0.75) = complex alginate-guma guar (raport<br />

0.75:0.75) ; AG1% = capsule alginat 1% ; AG -CAR (0.5:0.5) = complex alginat-k-carrageenan (raport<br />

0.5:0.5); AG -GG (0.5:0.5) = complex alginate-guma guar (raport 0.5:0.5); AG-XG (0.5:0.5) = complex<br />

alginate-guma xantan (raport 0.5:0.5)<br />

Măsurarea ratei de eliberare a uleiurilor din capsule<br />

Ca şi sisteme de eliberare s-au luat in considerare 3 solvenţi: tetrahidrofuran (THF),<br />

metanol si hexan. În toate cazuri s-a evidentiat o rapida eliberare in THF ca si solvent din<br />

toate capsule obtinute, si o mai lenta eliberare in cazul metanolului si o foarte slaba in cazul<br />

hexanului (vezi Fig.IV.2., graficele fiind parte din lucrarea publicata in revista Chemické<br />

Listy Journal (IF=0.683)). THF este considerat şi în litaratura ca fiind solventul cel mai<br />

eficient în extracţia carotenoidelor, lucru dovedit şi în acest studiu. Rata de eliberare a<br />

uleiurilor din capsule depinde de difuzitatea şi solubilitatea uleiului în matrice.<br />

Eliberarea uleiurilor din capsule a demonstrat faptul ca alginatul, complexul dintre<br />

alginat cu k-caragenan şi gume, precum şi chitosanul, sunt matrici pretabile la încapsularea<br />

uleiurilor vegetale.<br />

XXIV

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

A.<br />

B.<br />

Absorbance (u.a.)<br />

Absorbance (a.u.)<br />

0.4<br />

0.35<br />

0.3<br />

0.25<br />

0.2<br />

0.15<br />

0.1<br />

0.05<br />

0.7<br />

0.6<br />

0.5<br />

0.4<br />

0.3<br />

0.2<br />

0.1<br />

0<br />

0<br />

0 100 200<br />

Wavelenght (nm)<br />

300 400<br />

0 100 200<br />

Wavelenght (nm)<br />

300 400<br />

Fig.IV.2. Reprezentarea grafica a eliberarii in timp din diferitele capsule in metanol si hexan, ca si solventi<br />

Eliberarea in vitro a uleiurilor din capsule<br />

Alginate-carrageenan<br />

complex in hexane<br />

Alginate-carrageenan<br />

complex in methanol<br />

Alginate 2% in methanol<br />

Alginate 2% in hexane<br />

Chitosan 1.5% in methanol<br />

Chitosan 1% in methanol<br />

Chitosan 1% in hexane<br />

Chitosan 1.5% in hexane<br />

Alginate 2% in methanol<br />

Alginate 2% in hexane<br />

În cazul mimării mediului digestiv s-a demosntrat stabilitatea capsulelor la pH 1.2 si pH<br />

4.5, dizolvarea acestora si eliberarea continutului realizandu-se la pH 7.4, atat in cazul<br />

solutiilor continand enzime cat si a celor fara continut enzimatic în cazul capsulelor din<br />

alginat şi alginat în complex cu k-caragenan şi gume (Fig.IV.3.), ceea ce demonstreaza<br />

aplicabilitatea viitoare a acestor capsule continand ulei de catina ca si nutraceutice sau in<br />

industria farmaceutica. Capsulele de chitosan nu s-au dizolvat la nici unul dintre pH-urile<br />

testate.<br />

XXV

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

A. B.<br />

C. D.<br />

Fig.IV.3. Eliberarea ”in vitro” a uleiului de catina din capsulele de alginate 2% de la stanga la dreapta in fiecare<br />

poza fluidele stimulatoare fara enzyme si cu adios de enzyme (Sanzyme): A. capsulele obtinute; B. dupa 1 ora in<br />

stimulatul fluid gastric la pH 1.2; C. dupa 3 ore in mixul dintre fluidul gastric si fluidul intestinal la pH 4.5; D. in<br />

stimulatul fluid intestinal pH 7.4 dupa 30 minute<br />

IV.3. CONCLUZII<br />

Studiile referitoare la eficienţa încapsulării şi stabilitatea capsulelor conţinând uleiuri au<br />

demonstrat:<br />

1. Creşterea concentraţiei matricilor sau a complexului de matrici determină obţinerea<br />

unei mai bune eficienţe la încapsulare. s-a obţinut cea mai bună eficienţa a încapsulării<br />

utilizând ca şi matrici: alginatul în concentraţie de 2%, chitosanul in aceeaşi<br />

concentraţie, urmate de concentraţiile de 1.5%, şi de alginatul în complex cu kcaragenan<br />

şi gume în raport de 0.75:0.75%.<br />

2. Rata de eliberare a uleiurilor din capsule depinde de difuzitatea şi solubilitatea uleiului<br />

în matrice. Eliberarea a fost mai lentă in cazul hexanului, mai ridicată în cazul<br />

metanolului şi cea mai buna eliberare fiind in THF, indiferent de matricea sau<br />

concentraţia utilizată la încapsulare.<br />

3. Stabilitatea capsulelor la pH 1.2 si pH 4.5, dizolvarea acestora şi eliberarea<br />

continutului realizandu-se la pH 7.4.<br />

XXVI

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

CAPITOL V. CARACTERIZAREA FTIR A OXIDĂRII ULEIURILOR<br />

V.1. MATERIALE ŞI METODE<br />

Analiza spectrala in domeniul IR s-a utilizat spectrofotometru FT-IR Shimadzu<br />

Prestige-21, echipat cu Reflectanta Totala Atenuata Orizontala (HATR), cu accesoriu de<br />

ZnSe. Masuratorile au fost efectuate in domeniul infrarosu 650-4000 cm -1 , 100 scanari fiecare<br />

proba la rezolutia 2 cm -1 . Dupa fiecare proba accesoriul a fost spalat cu acetona.<br />

Uleiurile libere si capsulele cu uleiuri au fost supuse in vederea oxidarii la temperatura<br />

de 105ºC, si la iradiere UV (254µm) timp de o ora, 4 ore si 6 ore.<br />

S-au inregistrat spectrele FTIR-ATR dupa fiecare oxidare, atat la uleiul liber cat si<br />

extras din capsule. In cazul analizelor FTIR-ATR au fost posibile inregistrarea spectrelor<br />

capsulelor cu ulei, nefiind necesara extracţia uleiului din capsule.<br />

V.2. REZULTATE ŞI DISCUŢII<br />

În cazul analizelor FTIR-ATR a fost stabilit stadiul oxidării, calculandu-se raportul<br />

între intensităţile principalele peakuri considerate markeri ai oxidarii conform literaturi<br />

(Guillén and Cabo, 1999, 2000, 2002): A2853/A3005, A1746/A3006, A1474/A3006, A1377/A3006 and<br />

A1163/A3006, înainte şi după tratamentul UV.<br />

S-a constat ca uleiul liber avea un stagiu mai avansat al oxidarii 2 sau 3, in timp ce<br />

uleiul incapsulat se afla in stagiu 1 al oxidarii. S-a demosntrat astfel ca uleiul de catina<br />

incapsulat in diferitele capsule obtinute din matricile utilizate a fost mult mai protejat<br />

impotriva oxidarii in urma diferitelor tratamente, comparativ cu uleiul liber (ex: la uleiul de<br />

cătină, Fig.V.1.).<br />

Cea mai bună protecţie împotriva oxidării a fost asigurată de urmatoarele capsule<br />

formate din matrcile şi concentraţiile urmatoare: alginat 1%, chitosan 1.5%, complexele<br />

alginate-gumă gum şi alginat-gum xantan în raport 0.5:0.5, şi alginat-k-caragenan complex în<br />

raport 0.75:0.75.<br />

XXVII

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Ratio values/Valoarea raportelor<br />

8<br />

7<br />

6<br />

5<br />

4<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

0<br />

A B C D E A B C D E A B C D E<br />

After 1h UV/Dupa 1h<br />

UV<br />

After 4h UV/Dupa 4h<br />

UV<br />

After 6h UV/Dupa 6h<br />

UV<br />

Types of ratios on time/Tipul rapoartelor in timp<br />

Oil free/Ulei liber<br />

Oil from AG 1%/Ulei din AG 1%<br />

Oil from AG 1.5%/Ulei din AG 1.5%<br />

Oil from AG 2%/Ulei din AG 2%<br />

Fig. V.1. Reprezentarea grafica a uleiului de canepa liber si incapsulate (in diferite capsule<br />

de alginate) in timpul oxidarii<br />

(A= A2853/A3005-3008, B= A1744/ A3005-3008, C= A1464/ A3005-3008, D= A1377/ A3005-3008, E= A1160/<br />

A3005-3008)<br />

V.3. CONCLUZII<br />

Uleiurile încapsulate prezintă o mai buna stabilitate împotriva oxidării provocate de<br />

diferite conditii comparativ cu uleiurile libere.<br />

Cea mai bună protecţie împotriva oxidării a fost asigurată de urmatoarele capsule<br />

formate din matrcile şi concentraţiile urmatoare: alginat 1%, chitosan 1.5%, complexele<br />

alginate-gumă gum şi alginat-gum xantan în raport 0.5:0.5, şi alginat-k-caragenan complex în<br />

raport 0.75:0.75.<br />

Spectroscopia FTIR este considerată o foarte buna tehnică de monitorizare a oxidării<br />

uleiurilor libere şi încapsulate, dovedindu-se totodată a fi o tehnică rapidă, acurată şi simplă.<br />

XXVIII

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

CONCLUZII GENERALE<br />

În conformitate cu scopul si obiectivele acestei teze de doctorat, s-a realizat<br />

bioîncapsularea a patru uleiuri funcţionale din plante în diferite matrici naturale, precum şi<br />

evaluarea eficienţei încapsulării, stabilitatea şi eliberarea uleiurilor din capsulele obtinute.<br />

S-a realizat o evaluare comparativă si sistematică a calităţii celor patru uleiuri<br />

funcţionale din plante înaintea încapsulării lor: uleiul de cânepă (HP), uleiul extra virgin de<br />

măsline (EVO), uleiul de dovleac (PK) şi uleiul de cătină (SB) (de provenienţă din România<br />

şi Italia).<br />

Având în vedere obiectivele propuse s-a realizat:<br />

I. S-au identificat caracteristicile uleiurilor înainte de încapsulare, stabilindu-se<br />

markeri de calitate si autenticitate:<br />

1. Majoritatea uleiurilor analizate prezintă indicele de iod în conformiatte cu<br />

specificaţiile din CODEX 210, excepţie uleiul de cătină care prezintă a valoare mai<br />

scazută.<br />

2. Spectrele UV-Vis ale uleiurilor au relevant peakurile specifice, ca şi markeri ai<br />

autenticităâii.<br />

3. Studiile FTIR-ATR au demonstrat relaţia dintre benzile aparute în spectre şi<br />

compoziţia specifică fiecarui ulei, putându-se astfel stabili fingerprintul specific<br />

uleiurilor studiate.<br />

4. Analizele GC-FID au demonstrate faptul rpofilul acizilor din compoziţia uleiurilor<br />

analizate este în conformitate cu datele din literatură.<br />

II. Studiile experimentale utilizând ca şi metodă gelarea ionicăde<br />

numită:‘’ionotropically crosslinked gelation’’, în vederea bioîncapsulării uleiurilor<br />

funcţionale în matrici naturale, au demonstrat stabilitatea şi eliberarea controlată a<br />

uleiurilor bioîncapsulate<br />

1. S-a reusit obţinerea diferitelor tipuri de capsule utilizănd matrici naturale şi<br />

complexe dintre acestea, fiind incorporate uleiuri<br />

2. Caracteristicile capsulelor obţinute (aria, perimetrul, compactitatea, sfericitatea şi<br />

elongaţia), în special mărimea lor, au fost influenţate de conţinutul de uleiuri<br />

încapsulate.<br />

3. Cele mai bune matrici pentru bioîncapsularea uleiurilor au fost: alginat 2%,<br />

chitosan 2%, şi alginate în complex cu k-caragenan, gumă guar şi gumă xantan în<br />

raport de 0.75:0.75.<br />

III. Caracterizarea capsulelor a fost realizată prin diferite metode: SEM, FTIR,<br />

analize DSC şi TGA<br />

1. Suprafata capsulelor analizată prin SEM, a fost non-regulara, aceasta datorita<br />

picaturilor de ulei prezente, exceptand chitosanul care prezinta o suprafata mult<br />

mai mata<br />

XXIX

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

2. Prin analizele FTIR-ATR, diferitele capsule conţinând uleiuri au prezentat peakuri<br />

care sunt atribuite atat uleiurilor cât şi capsulelor goale (regiunile dintre 2800-2900<br />

cm -1 şi 1700-900 cm -1 ).<br />

3. Termogramele DSC au arătat faptul că temperature peakurilor creşte direct<br />

proportional cu cresterea temperaturii, fiecare peak fiind characteristic fiecărui tip<br />

de capsula obţinută.<br />

4. Analizele TGA au demonstrate ca pierderea în greutate se datoreaza continutului<br />

ridicat in apa a unor capsule. Încapsularea uleiurilor nu afectează pierderea în<br />

greutate a capsulelor.<br />

IV. Evaluarea eficienţei încapsulării<br />

1. Creşterea concentraţiei matricilor sau a complexului de matrici determină<br />

obţinerea unei mai bune eficienţe la încapsulare. s-a obţinut cea mai bună eficienţa<br />

a încapsulării utilizând ca şi matrici: alginatul în concentraţie de 2%, chitosanul in<br />

aceeaşi concentraţie, urmate de concentraţiile de 1.5%, şi de alginatul în complex<br />

cu k-caragenan şi gume în raport de 0.75:0.75%.<br />

2. Rata de eliberare a uleiurilor din capsule depinde de difuzitatea şi solubilitatea<br />

uleiului în matrice. Eliberarea a fost mai lentă in cazul hexanului, mai ridicată în<br />

cazul metanolului şi cea mai buna eliberare fiind in THF, indiferent de matricea<br />

sau concentraţia utilizată la încapsulare.<br />

3. Stabilitatea capsulelor la pH 1.2 si pH 4.5, dizolvarea acestora şi eliberarea<br />

continutului realizandu-se la pH 7.4.<br />

V. Protecţia bioîncapsulării a uleiurilor împotriva<br />

1. Uleiurile încapsulate prezintă o mai buna stabilitate împotriva oxidării provocate<br />

de diferite conditii comparativ cu uleiurile libere.<br />

2. Cea mai bună protecţie împotriva oxidării a fost asigurată de urmatoarele capsule<br />

formate din matrcile şi concentraţiile urmatoare: alginat 1%, chitosan 1.5%,<br />

complexele alginate-gumă gum şi alginat-gum xantan în raport 0.5:0.5, şi alginatk-caragenan<br />

complex în raport 0.75:0.75.<br />

XXX

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

BIBLIOGRAFIE SELECTIVĂ<br />

1. AOAC, 1980, Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical<br />

Chemistry. 13th Ed., AOAC, Washington DC<br />

2. AOAC, 1984, Iodine absorption number of oils and fats. In AOAC official methods<br />

of analysis (14th ed.). Washington, DC, 506<br />

3. BAETEN, V., AND APARICIO, R., 2000, Edible oils and fats authentication by<br />

Fourier transform Raman spectrometry, Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 4 (4), 196–<br />

203.<br />

4. BAETEN, V., AND PIERNA, J. A. F., 2005, Detection of the presence of hazelnut<br />

oil in olive oil by FTRaman and FT-MIR spectroscopy, Journal of Agricultural and<br />

Food Chemistry, 53, 6201-6206.<br />

5. BENITA S., 2006, Microencapsulation-Methods and Industrial Applications, 2 nd<br />

edition, Taylor&Francis, CRC Press, New York.<br />

6. BIRNBAUM, D.T., AND BRANNON-PEPPAS, L., 2003, Molecular weight<br />

distribution changes during degradation and release of PLGA nanoparticles containing<br />

epirubicin HCl, Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition, 14 (1), 87-102.<br />

7. CODEX ALIMENTARIUS, CODEX STANDARD FOR OLIVE OIL, VIRGIN<br />

AND REFINED, AND FOR REFINED OLIVE-POMACE OIL CODEX STAN 33-<br />

1981 (Rev. 1-1989), 25-39.<br />

8. CODEX-STAN 210, CODEX STANDARD FOR NAMED VEGETABLE OILS,<br />

(Amended 2003, 2005), 1-13.<br />

9. CODEX-STAN 210, Other quality and composition factors Commission Regulation<br />

(EEC) no. 2568/91, J. Eur. Commun., No. L, 248, 5.9.91, CODEX STANDARD FOR<br />

OLIVE OIL, VIRGIN AND REFINED, AND FOR REFINED OLIVE-POMACE<br />

OIL CODEX STAN 33-1981 (Rev. 1-1989).<br />

10. DAI, Z., VOIGT, A., DONATH, E., MÖHWALD, H., 2001, Novel Encapsulated<br />

Functional Dye Particles Based on Alternately Adsorbed Multilayers of Active<br />

Oppositely Charged Macromolecular Species, Macromolecular Rapid<br />

Communications, 22 (10), 756 – 762.<br />

11. DE MAN J.M., 1992, Chemical and physical properties of fatty acids, In: Chow CK<br />

(ed) Fatty Acids in Foods and Their Health Implications. Marcel Dekker Inc. New<br />

York, 18 – 46.<br />

12. DHANIKULA AB, AND PANCHAGNULA R., 2004, Development and<br />

Characterization of Biodegradable Chitosan Films for Local Delivery of Paclitaxel,<br />

The AAPS Journal, 6 (3), Article 27.<br />

13. DULIEU, C., PONCELET, D., NEUFELD, R., 1999, Encapsulation and<br />

immobilization techniques, In: Cell Encapsulation Technology and Therapeutics,<br />

W.M. Kühtreiber, R.P. Lanza and W.L. Chick, eds., Birkhäuser, Boston, 3-17<br />

14. DZIEEZAK, J.D., 1988, Microencapsulation and encapsulated ingredients, Food<br />

Technol. 45(4), 136.<br />

15. GUILLEN, M. D. AND CABO, N., 1997, Characterization of edible oils and lard by<br />

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Relationships between composition and<br />

frequency of concrete bands in the fingerprint region, J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc., 74 (10),<br />

1281–1286.<br />

16. GUILLEN, M. D. AND CABO, N., 1997, Infrared Spectroscopy in the Study of<br />

Edible Oils and Fats, J Sci Food Agric., 75, 1-11.<br />

17. GUILLEN, M. D. AND CABO, N., 1998, Relationships between the composition of<br />

edible oils and lard and the ratio of the absorbance of specific bands of their Fourier<br />

XXXI

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

transform infrared spectra. Role of some bands of the fingerprint region, J. Agric.<br />

Food Chem., 46 (5), 1788–1793.<br />

18. GUILLEN, M. D. AND CABO, N., 1999, Usefulness of the frequencies of some<br />

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic bands for evaluating the composition of<br />

edible oil mixtures. Fett-Lipid, 101 (2), 71– 76.<br />

19. GUILLEN, M. D. AND CABO, N., 1999, Usefulness of the frequency data of the<br />

Fourier transform infrared spectra to evaluate the degree of oxidation of edible oils, J.<br />

Agric. Food Chem., 47 (2), 709– 719.<br />

20. GUILLEN, M. D. AND CABO, N., 2000, Some of the most significant changes in<br />

the Fourier transform infrared spectra of edible oils under oxidative conditions, J. Sci.<br />

Food Agric., 80 (14), 2028– 2036.<br />

21. GUILLEN, M. D. AND CABO, N., 2002, Fourier transform infrared spectra data<br />

versus peroxide and anisidine values to determine oxidative stability of edible oils,<br />

Food Chem., 77 (4), 503–510.<br />

22. GUILLEN, M.D., CARTON, I., GOICOECHEA, E. AND URIARTE, P.S., 2008,<br />

Characterization of Cod Liver Oil by Spectroscopic Techniques. New Approaches for<br />

the Determination of Compositional Parameters, Acyl Groups, and Cholesterol from<br />

1H Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectral Data, J.<br />

Agric. Food Chem., 56, 9072–9079.<br />

23. HEINZEN, C., 2002, Microencapsulation solve time dependent problems for<br />

foodmakers. European Food and Drink Review, 3, 27–30.<br />

24. KRAJEWSKA, B., 2005, Membrane-based Processes Performed with use of<br />

Chitin/Chitosan Materials, Separation & Purification Technology, 41, 305–312.<br />

25. LAPITSKY, Y. AND KALER, E. W., 2006, Surfactant and polyelectrolyte gel<br />

particles for encapsulation and release of aromatic oils, Soft Matter, 2, 779-784.<br />

26. LICHTENTHALER H.K., BUSCHMANN C., 2001, Chlorophylls and carotenoids:<br />

measurement and characterization by UV-VIS spectroscopy. Curr. Prot. Food Anal.<br />

Chem. F4.3.1 – F 4.3.8.<br />

27. MADDUR NAGARAJU SATHEESH KUMAR, SIDDARAMAIA, 2007,<br />

Thermogravimetric Analysis and Morphological Behavior of Castor Oil Based<br />

Polyurethane–Polyester Nonwoven Fabric Composites, Journal of Applied Polymer<br />

Science, 106, 3521–3528.<br />

28. MATEA, C.T., NEGREA, O., HAS, I., IFRIM, S., BELE, C., 2008, Tocopherol and<br />

fatty acids contents of selected Romanian cereals grains, Chem. Listy, 99, 1234-2345.<br />

29. OZEN, B. F. AND MAUER, L. J., 2002, Detection of Hazelnut Oil Adulteration<br />

Using FT-IR Spectroscopy, J. Agric. Food Chem., 50 (14), 3898–3901.<br />

30. OZEN, B. F., WEISS, I., et al., 2003, Dietary supplement oil classification and<br />

detection of adulteration using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, Journal of<br />

Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 51, 5871-5876.<br />

31. PARTANEN, R., YOSHII, H., KALLIO, H., YANG, B. AND FORSSELL, P.,<br />

2002, Encapsulation of sea buckthorn kernel oil in modified starches. Journal of the<br />

American Oil Chemists' Society (JAOCS), 79 (3), 219-223.<br />

32. PEREIRA, L., SOUSA, A., COELHO, H., AMADO, A.M., RIBEIRO-CLARO,<br />

P.J.A., 2003, Use of FTIR, FT-Raman and 13C-NMR spectroscopy for identification<br />

of some seaweed phycocolloids, Biomolecular Engineering, 20, 223-228.<br />

33. PFUTZE, S., 2003, Encapsulatation and granulation, XI International Workshop on<br />

Bioencapsulation, 3-6.<br />

34. PONCELET D., 2006, Microencapsulation: Fundamentals, methods and<br />

applications, in Surface Chemistry in Biomedical and Environmental Science ( Brlitz<br />

J. and Gunko K. eds), NATO Science Series, Springer verlag, 23-34.<br />

XXXII

Sisteme de încapsulare a unor compuşi bioactivi extraşi din uleiuri vegetale<br />