Untitled

Untitled Untitled

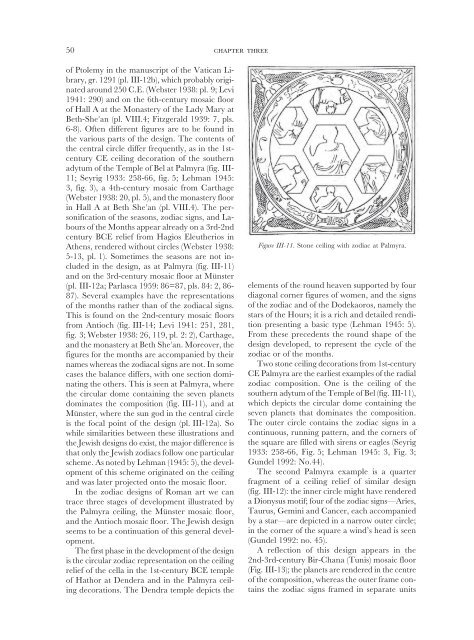

50 of Ptolemy in the manuscript of the Vatican Library, gr. 1291 (pl. III-12b), which probably originated around 250 C.E. (Webster 1938: pl. 9; Levi 1941: 290) and on the 6th-century mosaic floor of Hall A at the Monastery of the Lady Mary at Beth-She"an (pl. VIII.4; Fitzgerald 1939: 7, pls. 6-8). Often different figures are to be found in the various parts of the design. The contents of the central circle differ frequently, as in the 1stcentury CE ceiling decoration of the southern adytum of the Temple of Bel at Palmyra (fig. III- 11; Seyrig 1933: 258-66, fig. 5; Lehman 1945: 3, fig. 3), a 4th-century mosaic from Carthage (Webster 1938: 20, pl. 5), and the monastery floor in Hall A at Beth She"an (pl. VIII.4). The personification of the seasons, zodiac signs, and Labours of the Months appear already on a 3rd-2nd century BCE relief from Hagios Eleutherios in Athens, rendered without circles (Webster 1938: 5-13, pl. 1). Sometimes the seasons are not included in the design, as at Palmyra (fig. III-11) and on the 3rd-century mosaic floor at Münster (pl. III-12a; Parlasca 1959: 86=87, pls. 84: 2, 86- 87). Several examples have the representations of the months rather than of the zodiacal signs. This is found on the 2nd-century mosaic floors from Antioch (fig. III-14; Levi 1941: 251, 281, fig. 3; Webster 1938: 26, 119, pl. 2: 2), Carthage, and the monastery at Beth She"an. Moreover, the figures for the months are accompanied by their names whereas the zodiacal signs are not. In some cases the balance differs, with one section dominating the others. This is seen at Palmyra, where the circular dome containing the seven planets dominates the composition (fig. III-11), and at Münster, where the sun god in the central circle is the focal point of the design (pl. III-12a). So while similarities between these illustrations and the Jewish designs do exist, the major difference is that only the Jewish zodiacs follow one particular scheme. As noted by Lehman (1945: 5), the development of this scheme originated on the ceiling and was later projected onto the mosaic floor. In the zodiac designs of Roman art we can trace three stages of development illustrated by the Palmyra ceiling, the Münster mosaic floor, and the Antioch mosaic floor. The Jewish design seems to be a continuation of this general development. The first phase in the development of the design is the circular zodiac representation on the ceiling relief of the cella in the 1st-century BCE temple of Hathor at Dendera and in the Palmyra ceiling decorations. The Dendra temple depicts the chapter three Figure III-11. Stone ceiling with zodiac at Palmyra. elements of the round heaven supported by four diagonal corner figures of women, and the signs of the zodiac and of the Dodekaoros, namely the stars of the Hours; it is a rich and detailed rendition presenting a basic type (Lehman 1945: 5). From these precedents the round shape of the design developed, to represent the cycle of the zodiac or of the months. Two stone ceiling decorations from 1st-century CE Palmyra are the earliest examples of the radial zodiac composition. One is the ceiling of the southern adytum of the Temple of Bel (fig. III-11), which depicts the circular dome containing the seven planets that dominates the composition. The outer circle contains the zodiac signs in a continuous, running pattern, and the corners of the square are filled with sirens or eagles (Seyrig 1933: 258-66, Fig. 5; Lehman 1945: 3, Fig. 3; Gundel 1992: No.44). The second Palmyra example is a quarter fragment of a ceiling relief of similar design (fig. III-12): the inner circle might have rendered a Dionysus motif; four of the zodiac signs—Aries, Taurus, Gemini and Cancer, each accompanied by a star—are depicted in a narrow outer circle; in the corner of the square a wind’s head is seen (Gundel 1992: no. 45). A reflection of this design appears in the 2nd-3rd-century Bir-Chana (Tunis) mosaic floor (Fig. III-13); the planets are rendered in the centre of the composition, whereas the outer frame contains the zodiac signs framed in separate units

Figure III-12. Part of a stone ceiling with zodiac at Palmyra. (Gaukler 1910, no. 447; Lehman 1945: 5, n. 29; Hachlili 1977: fig. 9; Dunbabin 1978: 161, pl. 162; Gundel 1992: no. 210). However, rather than forming a continuous pattern, the zodiac signs on the Bir-Chana mosaic are framed in separate units. The next phase, represented by the 3rd-century Münster-Sarnsheim mosaic floor, has the same basic pattern (pl. III-12a). However, the frontal sun god has replaced the seven planets, and in the outer circle the zodiac signs are divided into individual units (Parlasca 1959: 86-87, pl. 42, 84: 2; Gundel 1992: No.84). The sun god in the central circle at Münster-Sarnsheim is the focal point of the design. In both the examples of Palmyra and Münster the central circle is the focal point, the zodiac signs are rendered as a narrow outer circle, and the objects situated diagonally in the corners of the square are similar in composition. The final phase, showing a more balanced re - pre sentation of the same pattern, is found in the 2nd-century mosaic floor from the triclinium in the ‘House of the Calendar’ at Antioch (fig. III-14). The central circle has become smaller, the outer circle larger (Webster 1938: 26, 119, pl. 2: 2; Levi 1941: 251, 281, fig. 3; 1947: 36-38; Stern 1953: 224-227, 256-258, 296, pl. XLII, 2; Campbell 1988: 60-62, fig. 24-25; pls. 183-185). 2 The Antioch mosaic pavement depicts the representations of the months rather than the zodiac signs. The 4 Hanfmann (1951: 248) maintains that ‘no later than the 2nd century CE, a type of composition in which the sun god is standing in his chariot, surrounded by the signs of the zodiac and the months with the tropai placed in the corners…the Seasons are not yet Seasons, but astronomical the zodiac panel and its significance 51 outer circle is divided into radial units containing the figures of the months, while the corners contain representations of the seasons. The inner circle has not survived. The development of the design in these examples of Roman art can be traced from ceiling to pavement, from Palmyra to Antioch; the growing number of calendar representations on mosaic floors proves an increasing attraction in the cyclic movement of time (Lehman 1945: 8- 9). The basic form remains the same: two concentric circles within a square. What changes is the composition of the various parts and the balance among them. A central circle containing the planets in a geometric design undergoes a transition to a centre with the sun god. A continuous, running zodiac in the outer circle is transformed gradually into one divided into radial units with a zodiac sign in each. The purely aesthetic design of sirens or fishes in the corners of the square is replaced by the functional, but still aesthetic, design of the seasons. Eventually the total design develops from those of Palmyra and Münster, where one section, the central circle, is dominant, to the more harmoniously balanced design of Antioch. The Jewish zodiac mosaic design, with the earliest Hammath Tiberias panel, thus seems related to the Antioch school and has its origins in Roman art. Each part of the design (central circle, outer circle, corners of the square) has comparable representations in the art of the preceding Roman period. Several examples of the calendar’s balanced circular design have survived from the late Roman and Byzantine periods. On the 4th-5th century mosaic pavement from Carthage the central circle contains a seated figure, probably representing Mother Earth. The outer circle renders in a continuous frieze the Labours of the Months, with their names inscribed above their heads. The outside spandrels contain four seated seasons inscribed with their names (Webster 1938: 20, pl. 5; Åkerström-Hougen 1974: 124, no. 5, fig. 80; Hachlili 1979: fig. 11; only a drawing of this mosaic is known). The most striking resemblances to the Jewish zodiac are found on two contemporary Roman- Byzantine mosaic pavements in Greece: tropai, the turning points of the sun during the year… Since these ‘Turning Points’ were represented with the attributes of Seasons, they are constantly confused with the seasons in later renderings’.

- Page 29 and 30: foreword xxvii FOREWORD התדיב

- Page 31 and 32: One of the most significant and fru

- Page 33 and 34: pavement at Caesarea the word is sp

- Page 35 and 36: mosaic pavements adorning buildings

- Page 37 and 38: mosaic pavements adorning buildings

- Page 39 and 40: mosaic pavements adorning buildings

- Page 41 and 42: mosaic pavements adorning buildings

- Page 43 and 44: mosaic pavements adorning buildings

- Page 45 and 46: mosaic pavements adorning buildings

- Page 47 and 48: Introduction: Jewish Figurative Art

- Page 49 and 50: Figure II-3. Beth "Alpha synagogue:

- Page 51 and 52: to the Sefer HaRazim Yahoweh reside

- Page 53 and 54: ut all served as repositories for t

- Page 55 and 56: pomegranates and cups (Hachlili 200

- Page 57 and 58: open ark with scrolls is depicted,

- Page 59 and 60: are rendered in non-identical symme

- Page 61 and 62: pavements of Samarian synagogues an

- Page 63 and 64: of two columns surmounting an arche

- Page 65 and 66: A group of ancient synagogues disco

- Page 67 and 68: the zodiac panel and its significan

- Page 69 and 70: the zodiac panel and its significan

- Page 71 and 72: the zodiac panel and its significan

- Page 73 and 74: the zodiac panel and its significan

- Page 75 and 76: the bust of the season Nisan (Sprin

- Page 77 and 78: The Summer attributes, the sickle a

- Page 79: Table III-1. Comparative chart of t

- Page 83 and 84: A Roman villa at Odos Triakosion in

- Page 85 and 86: the four seasons, representing the

- Page 87 and 88: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 89 and 90: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 91 and 92: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 93 and 94: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 95 and 96: Noah’s Ark biblical narrative the

- Page 97 and 98: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 99 and 100: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 101 and 102: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 103 and 104: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 105 and 106: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 107 and 108: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 109 and 110: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 111 and 112: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 113 and 114: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 115 and 116: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 117 and 118: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 119 and 120: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 121 and 122: Jonah biblical narrative themes and

- Page 123 and 124: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 125 and 126: iblical narrative themes and images

- Page 127 and 128: Nilotic scenes are a recurrent them

- Page 129 and 130: iconographic elements of nilotic sc

50<br />

of Ptolemy in the manuscript of the Vatican Library,<br />

gr. 1291 (pl. III-12b), which probably originated<br />

around 250 C.E. (Webster 1938: pl. 9; Levi<br />

1941: 290) and on the 6th-century mosaic floor<br />

of Hall A at the Monastery of the Lady Mary at<br />

Beth-She"an (pl. VIII.4; Fitzgerald 1939: 7, pls.<br />

6-8). Often different figures are to be found in<br />

the various parts of the design. The contents of<br />

the central circle differ frequently, as in the 1stcentury<br />

CE ceiling decoration of the southern<br />

adytum of the Temple of Bel at Palmyra (fig. III-<br />

11; Seyrig 1933: 258-66, fig. 5; Lehman 1945:<br />

3, fig. 3), a 4th-century mosaic from Carthage<br />

(Webster 1938: 20, pl. 5), and the monastery floor<br />

in Hall A at Beth She"an (pl. VIII.4). The personification<br />

of the seasons, zodiac signs, and Labours<br />

of the Months appear already on a 3rd-2nd<br />

century BCE relief from Hagios Eleutherios in<br />

Athens, rendered without circles (Webster 1938:<br />

5-13, pl. 1). Sometimes the seasons are not included<br />

in the design, as at Palmyra (fig. III-11)<br />

and on the 3rd-century mosaic floor at Münster<br />

(pl. III-12a; Parlasca 1959: 86=87, pls. 84: 2, 86-<br />

87). Several examples have the representations<br />

of the months rather than of the zodiacal signs.<br />

This is found on the 2nd-century mosaic floors<br />

from Antioch (fig. III-14; Levi 1941: 251, 281,<br />

fig. 3; Webster 1938: 26, 119, pl. 2: 2), Carthage,<br />

and the monastery at Beth She"an. Moreover, the<br />

figures for the months are accompanied by their<br />

names whereas the zodiacal signs are not. In some<br />

cases the balance differs, with one section dominating<br />

the others. This is seen at Palmyra, where<br />

the circular dome containing the seven planets<br />

dominates the composition (fig. III-11), and at<br />

Münster, where the sun god in the central circle<br />

is the focal point of the design (pl. III-12a). So<br />

while similarities between these illustrations and<br />

the Jewish designs do exist, the major difference is<br />

that only the Jewish zodiacs follow one particular<br />

scheme. As noted by Lehman (1945: 5), the development<br />

of this scheme originated on the ceiling<br />

and was later projected onto the mosaic floor.<br />

In the zodiac designs of Roman art we can<br />

trace three stages of development illustrated by<br />

the Palmyra ceiling, the Münster mosaic floor,<br />

and the Antioch mosaic floor. The Jewish design<br />

seems to be a continuation of this general development.<br />

The first phase in the development of the design<br />

is the circular zodiac representation on the ceiling<br />

relief of the cella in the 1st-century BCE temple<br />

of Hathor at Dendera and in the Palmyra ceiling<br />

decorations. The Dendra temple depicts the<br />

chapter three<br />

Figure III-11. Stone ceiling with zodiac at Palmyra.<br />

elements of the round heaven supported by four<br />

diagonal corner figures of women, and the signs<br />

of the zodiac and of the Dodekaoros, namely the<br />

stars of the Hours; it is a rich and detailed rendition<br />

presenting a basic type (Lehman 1945: 5).<br />

From these precedents the round shape of the<br />

design developed, to represent the cycle of the<br />

zodiac or of the months.<br />

Two stone ceiling decorations from 1st-century<br />

CE Palmyra are the earliest examples of the radial<br />

zodiac composition. One is the ceiling of the<br />

southern adytum of the Temple of Bel (fig. III-11),<br />

which depicts the circular dome containing the<br />

seven planets that dominates the composition.<br />

The outer circle contains the zodiac signs in a<br />

continuous, running pattern, and the corners of<br />

the square are filled with sirens or eagles (Seyrig<br />

1933: 258-66, Fig. 5; Lehman 1945: 3, Fig. 3;<br />

Gundel 1992: No.44).<br />

The second Palmyra example is a quarter<br />

fragment of a ceiling relief of similar design<br />

(fig. III-12): the inner circle might have rendered<br />

a Dionysus motif; four of the zodiac signs—Aries,<br />

Taurus, Gemini and Cancer, each accompanied<br />

by a star—are depicted in a narrow outer circle;<br />

in the corner of the square a wind’s head is seen<br />

(Gundel 1992: no. 45).<br />

A reflection of this design appears in the<br />

2nd-3rd-century Bir-Chana (Tunis) mosaic floor<br />

(Fig. III-13); the planets are rendered in the centre<br />

of the composition, whereas the outer frame contains<br />

the zodiac signs framed in separate units