Promise of Time.pdf

Promise of Time.pdf

Promise of Time.pdf

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

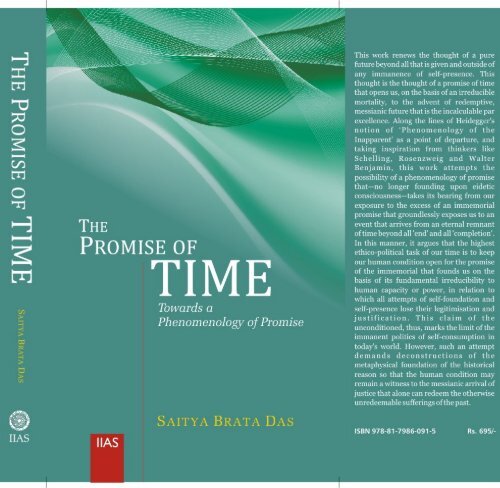

THE PROMISE OF TIME

SAITYA BRATA DAS<br />

Th e <strong>Promise</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Time</strong><br />

Towards a Phenomenology <strong>of</strong> <strong>Promise</strong><br />

INDIAN INSTITUTE OF ADVANCED STUDY<br />

RASHTRAPATI NIVAS, SHIMLA

First published 2011<br />

© Indian Institute <strong>of</strong> Advanced Study, Shimla<br />

All rights reserved.<br />

No part <strong>of</strong> this book may be reproduced<br />

or transmitted, in any form or by any means,<br />

without the written permission <strong>of</strong> the publisher.<br />

ISBN: 978-81-7986-091-5<br />

Published by<br />

Th e Secretary<br />

Indian Institute <strong>of</strong> Advanced Study<br />

Rashtrapati Nivas, Shimla-171005<br />

Typeset at Sai Graphic Design, New Delhi<br />

and printed at Pearl Off set Pvt. Ltd., Kirti Nagar, New Delhi

For<br />

My dear father<br />

Who fi rst taught me to love<br />

Th e love <strong>of</strong> wisdom: philo-sophia

Acknowledgements<br />

We never come to thoughts. Th ey come to us.<br />

—Martin Heidegger<br />

What does it mean to be thankful, and to say ‘thanks’? Th is question,<br />

which is at the very heart <strong>of</strong> an essential thinking, <strong>of</strong> language and <strong>of</strong><br />

our relation to the others, is what has always been a matter <strong>of</strong> thinking<br />

for me, as if, as it were, to think itself is to thank, to be thankful for<br />

the arrival <strong>of</strong> thinking. Th erefore, thinkers like Martin Heidegger<br />

see the connection, nay, discover at the very heart <strong>of</strong> thinking—for<br />

thinking too has its heart, it too has its tears and ecstasy—the light<br />

<strong>of</strong> thankfulness: to think is to thank, to be thankful, thankful for the<br />

advent <strong>of</strong> thinking, for the event <strong>of</strong> thinking coming to us. Th erefore,<br />

a thinker does not possess thinking, even less knowledge: thinking is<br />

what is gifted to the thinker for which he says, simply, ‘thanks’. Th ere<br />

lies the dignity and nobility <strong>of</strong> thinking itself.<br />

So I thank, not only for the gift <strong>of</strong> thinking coming to me, for<br />

this mournful joy <strong>of</strong> the experience <strong>of</strong> thinking, but all those and all<br />

that who inspired me have continued to inspire me to open myself<br />

to the joyous coming <strong>of</strong> thinking; all those who shared the ecstasy<br />

and tears <strong>of</strong> my thinking. Th ere is Franson Manjali, under whose<br />

inspiration I have written from the day I met him, and I will write<br />

in the days to come, whatever will come to me as gift, this event <strong>of</strong><br />

thinking. Th ere is Soumyabrata Choudhury, my loving brother, from<br />

whom I have learnt so much, learning never to lose myself in despair<br />

and hopelessness. Renowned French Philosopher Gérard Bensussan,<br />

who was my mentor during my stay at Université Strasbourg and at

viii • Acknowledgements<br />

Maison des Sciences de L’Homme, Paris where I was a post doctorate<br />

fellow during 2006-2007, the one who has never ceased to be<br />

my mentor, my philosopher and teacher for all these years. From<br />

him I have learnt a great deal, namely, to ‘philosophize’. To him I<br />

acknowledge hereby my deepest gratitude. Th anks to the advent <strong>of</strong><br />

Sarita, my beloved wife, who has inspired me to live my life anew;<br />

from whom once more I have learnt to see the open sea and the blue<br />

sky. Th ese people have had hopes in me and this manuscript recounts,<br />

in its own way, the story <strong>of</strong> such a hope contra all hopelessness, and<br />

the necessity <strong>of</strong> such an affi rmation.<br />

Th anks to this beautiful Shimla and this wonderful Institute that<br />

have both soothed my wounded soul at a diffi cult period <strong>of</strong> life; all the<br />

lovely people with whom I lived, joyously; all the local, lovely friends<br />

I have made at Shimla—Mridula and Pankaj above all—who gave<br />

me company in my lonely hours, away from home and away from<br />

Delhi. Th e Director, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Peter Ronald deSouza has inspired me<br />

in his own peculiar way, without words, silently, whose language I<br />

felt I understood. I wish to thank hereby Dr. Debarshi Sen for his<br />

patience and pr<strong>of</strong>essional effi ciency with which he brought out this<br />

book in so little time. Mr. Ravi Shankar, the typesetter, has made this<br />

book look so beautiful; thanks goes to him as well!<br />

Th ere is my father who gifted me this life, whom I now gift this<br />

book, which has already been given to me by him. And thanks<br />

goes to the loveliest and sweetest mother <strong>of</strong> mine, and my siblings<br />

who have silently inspired me all these years, to whom I can return<br />

nothing but love and my infi nite gratitude. And, lastly, thanks to<br />

this manuscript itself, which henceforth will have its own life, which<br />

will now onwards live without me, outside and away from me, forget<br />

me and leave me without a name. Th is book, for some intimate<br />

reason, is dear to me, for somehow in it I have sought to translate<br />

the language <strong>of</strong> my own soul. But since now it is going out to the<br />

world, its language is no longer the language <strong>of</strong> my soul but I hope it<br />

will become the language <strong>of</strong> the world-soul where human beings live,<br />

suff er and hope for redemption.

Beginning at the moment <strong>of</strong> deepest catastrophe<br />

Th ere exists the chance for redemption.<br />

—Gershom Scholem

Th e following chapters have been published previously<br />

1. Th e fi rst chapter <strong>of</strong> the fi rst part Th e Open originally appeared in<br />

Kritike http://www.kritike.org/journal/issue_6/das_december2009.<br />

<strong>pdf</strong><br />

2. An earlier version <strong>of</strong> the second part Th e Lightening Flash<br />

appeared in Philosophical Forum (Willey Blackwell, fall 2010)<br />

vol. 41, issue 3, p. 315-345.<br />

3. Th e Abyss <strong>of</strong> Human Freedom is published in Journal <strong>of</strong> Indian<br />

Council <strong>of</strong> Philosophical Research, October-December 2010, vol.<br />

XXVII, no 4, p.91-104.<br />

4. Of Pain is published in Journal <strong>of</strong> Comparative and Continental<br />

philosophy (New York: Equinox Publishers, May 2011), vol. 3: 1.<br />

5. A revised version <strong>of</strong> the chapter Th e Metaphysics <strong>of</strong> Language<br />

is published as Th e Destinal Question <strong>of</strong> Language in Kriterion<br />

(Spring 2011, issue 123).<br />

6. Th e Commandment <strong>of</strong> Love: Messianicity and Exemplarity in<br />

Franz Rosenzweig is read as paper at the 6 th Annual Philosophy<br />

Conference at Athens Institute for Education and Research, held<br />

at Athens, Greece, held during 30 May - 2 June 2011.<br />

7. Fragments in Epilogue section is read as paper called Of Fatigue, Of<br />

Patience – Finitude, Writing, Mourning in a seminar on ‘Levinas<br />

– Blanchot: Penser La Diff erence’, organized by UNESCO, Paris<br />

from 13-16 November 2006.

Contents<br />

Acknowledgements vii<br />

Foreword by Gérard Bensussan xv<br />

Premise 1<br />

PROLOGUE<br />

§ Th e <strong>Promise</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Time</strong><br />

To Come/Th e Claim <strong>of</strong> Redemption and the Question<br />

<strong>of</strong> History/Truth beyond Cognition/Existence/Messianic/<br />

Th e Lightning Flash <strong>of</strong> Language/Wandering, Th inking/<br />

Confi guration Saying<br />

5<br />

§ Radical Finitude<br />

Th e Immemorial/Th e Mournful Gift/the Logic <strong>of</strong> the World/<br />

Mortality/Introducing this Work<br />

20<br />

PART I – CONFIGURATION<br />

§ Th e Open 39<br />

§ Judgement and History:<br />

Of History/ Metaphysics and Violence/Th e Passion <strong>of</strong><br />

Potentiality<br />

51<br />

§ Transfi guration, Interruption 76<br />

§ Th e Logic <strong>of</strong> Origin 87<br />

Of Beginning/Madness/Astonishment

xii • Contents<br />

§ Repetition 108<br />

Repetition and Recollection/ Moment<br />

§ Language and Death 119<br />

Th e States <strong>of</strong> Exception/Th e Facticity <strong>of</strong> Love and Th e<br />

Facticity <strong>of</strong> Language/Th e Gift <strong>of</strong> Language<br />

§ Confi guration 132<br />

Caesura/Th e Star <strong>of</strong> Redemption/ Discontinuous Finitude/<br />

En-framing, Revelation/Lightning, Clearing/ Constellation<br />

<strong>of</strong> Temporalities/ Transfi nitude<br />

PART II – THE LIGHTNING FLASH<br />

§ Th e Language <strong>of</strong> the Mortals<br />

Th e Presupposition//Kierkegaard’s Indirect Communication<br />

161<br />

§ Pain<br />

Work and Pain/Th e Melancholic Gift/ Naming and<br />

Overnaming/Th inking and Th anking<br />

175<br />

§ Apollo’s Lightning Strike<br />

Th e Lightning Flash/Th e Divine Violence<br />

201<br />

§ Revelation<br />

Th e Argument/Synthesis without Continuum/Language as<br />

Revelation in Schelling’s Philosophy <strong>of</strong> Freedom<br />

210<br />

PART III – EVENT<br />

§ Of Event 225<br />

Th e Question <strong>of</strong> Event and the Limit <strong>of</strong> Foundation/<br />

Freedom, <strong>Time</strong> and Existence/Origin, Leap, Event<br />

§ Love and Death 243<br />

§ Th e Sense <strong>of</strong> Freedom 251<br />

§ Th e Irreducible Remainder 267<br />

§ Th e Abyss <strong>of</strong> Human Freedom 291<br />

Th e No-Th ing <strong>of</strong> Freedom and the Finitude <strong>of</strong> Man/<br />

Causality as a Problem <strong>of</strong> Freedom/Philosophy as Strife

PART IV – MESSIANICITY<br />

§ Th e Commandment <strong>of</strong> Love 305<br />

Exemplarity <strong>of</strong> Translation/the Aporia <strong>of</strong> Love/Revelation <strong>of</strong><br />

Love/Th e Th eologico-Political<br />

PART V – ON PHILOSOPHY<br />

Contents • xiii<br />

§ Erotic and Philosophic 343<br />

§ On Philosophical Research 354<br />

Th e Th ought <strong>of</strong> Death/ Philosophical Research/Notes on this<br />

Work<br />

EPILOGUE<br />

Fragments 381<br />

Notes 399<br />

Bibliography 407<br />

Index 415

Foreword<br />

Between End and Beginning:<br />

The <strong>Time</strong> <strong>of</strong> Speech<br />

Th e beautiful book <strong>of</strong> Satya Das is committed to a phenomenology<br />

<strong>of</strong> promise and explores manifold ways in it. What animates this<br />

phenomenology <strong>of</strong> promise is explicitly inspired by a paradoxical<br />

‘phenomenology <strong>of</strong> the unapparent that the later Heidegger had<br />

named his aspirations. It can be said that the pages you are going<br />

to read contribute to it in a remarkable manner because they lean<br />

towards the exercises <strong>of</strong> it from a very singular angle and access. Th e<br />

developments devoted here to the question <strong>of</strong> the promise have a<br />

force and a fl ash which come to them from an indisputable source<br />

which supports them: the fecundity <strong>of</strong> time, the temporality bursting<br />

forth and stratifi ed by waiting, opening to the event, and the fi nitude<br />

opened to infi nity, wherein the idea that appears in us, according to<br />

Descartes, signifi es in the fi nal analysis this very opening. Th us the<br />

promise, this astonishing object if one can put it this way, evokes<br />

a style, a writing, a strategy <strong>of</strong> presentation (Darstellung) about<br />

which Satya Das explicates in the fi rst part, where one sees how the<br />

deployment <strong>of</strong> this enterprise here is held together with the rigour<br />

<strong>of</strong> a true philosophical research while also being able to emancipate<br />

oneself from one’s most forceful constraints, which results in the<br />

most remarkable originality.<br />

It is under this double and confl icting exigency according to<br />

which an ‘object’ commands a writing that messianism as such, and

xvi • Foreword<br />

especially its very paradigm, the messianic as the index <strong>of</strong> time comes<br />

to be <strong>of</strong> help in the most lively part <strong>of</strong> this work (I am thinking<br />

particularly <strong>of</strong> the fourth part <strong>of</strong> the book) and brings it relief with<br />

its counter-dialectical resources. For this ‘phenomenology <strong>of</strong> the<br />

promise’ is necessarily a phenomenology <strong>of</strong> the event and, therefore, a<br />

phenomenology <strong>of</strong> the impossible, which is not far from signifying (but<br />

that would indeed be a point that could be discussed—as we used to do<br />

together in Strasbourg not long ago!) an impossible phenomenology.<br />

What is really an event if not an aff ectivity preceding its own<br />

possibility? How, then, can such impossible, impossible before being<br />

real, allows it to be thought, and furthermore, phenomenological<br />

thought? Satya Das does this according to the time <strong>of</strong> the end and<br />

the time <strong>of</strong> beginning and he does it again as well on the basis <strong>of</strong><br />

language.<br />

Th e author here explains in particular that the event bears together<br />

and supports the end and the beginning ‘in a monstrous coupling’<br />

which would signify something like a logic <strong>of</strong> the world. Th ere is,<br />

in fact, between the end and beginning a complex pairing that the<br />

messianism alone can achieve to determine it without elucidating it,<br />

according to a causal knowledge. Th e end promises. Th e beginning<br />

begins only from a kind <strong>of</strong> impossibility; because it promises the<br />

promise. Th us, what messianism names fi rst and foremost is an<br />

experience <strong>of</strong> temporality <strong>of</strong> the awaiting and <strong>of</strong> the decision, and <strong>of</strong><br />

the relation to the expected event and its reversal. Th us, messianism<br />

would be an irremissible impossibility <strong>of</strong> thinking whatever is referred<br />

to as the ‘origin’. ‘Th e origin’ will always be older than the objects we<br />

want to genealogize by retracing them to their point <strong>of</strong> departure. It<br />

forbids or interrupts the possibility <strong>of</strong> linking the beginning and the<br />

end as two ‘moments’, two given ‘points <strong>of</strong> time’ that are indiff erent<br />

and interlinked by virtue <strong>of</strong> their being having qualitatively similar<br />

presents. Formalized representations <strong>of</strong> time force us to consider that<br />

what happens in the present at a given ‘point <strong>of</strong> time’ could also<br />

happen in an ‘other’ present having the same quality <strong>of</strong> presence,<br />

at a given ‘point <strong>of</strong> time’ that is anterior and similar. It is against<br />

these representations that messianism has its signifi cance. And that’s<br />

where we grasp its fundamental diff erence in relation to teleology,<br />

eschatology, progressivism and all types <strong>of</strong> fi nalism. Freedom,<br />

existence and experienced time from then on appear as the very

Foreword • xvii<br />

endurance <strong>of</strong> the unexpected and unconditional <strong>of</strong> the messianic<br />

arrival and it is Satya Das’ own style <strong>of</strong> working with this messianic<br />

paradigm that I on my part have tried to elaborate as a novel thought<br />

<strong>of</strong> the event.<br />

To say that the beginning promises the promise is to say that it<br />

puts it ahead <strong>of</strong> itself. Th e beginning is the diff erence, altogether the<br />

coming <strong>of</strong> the promise (without beginning, there’s no promise) and<br />

the projection that dismisses its very appearance (without beginning,<br />

the promise would always be accomplished ipso facto). It is the<br />

promise itself that is promised and it is time itself which is structured<br />

like promise.<br />

As the title Th e <strong>Promise</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Time</strong> suggests, this promising structure<br />

<strong>of</strong> time is co-originarily associated with the question <strong>of</strong> language,<br />

a paradisiacal language in which the spoken language <strong>of</strong> naming is<br />

restrained and reserved. Here the inspiration comes from Rosenzweig<br />

who was able to link time and the waiting for language and<br />

the alterity <strong>of</strong> the other man, who is speaking and awaiting. Th e<br />

delinking, or in the fi nal analysis, redemption itself commands the<br />

‘never ultimate’ <strong>of</strong> the relation to the other, <strong>of</strong> the speech addressed<br />

to him, <strong>of</strong> time and <strong>of</strong> the absolute indetermination <strong>of</strong> the Messiah.<br />

Rosenzweig’s ‘never ultimate’ intends an arrival but without ever<br />

leaving for the assured departure <strong>of</strong> a language to be translated. Such<br />

is the fi ne line along which all speech moves. We always counter pose<br />

the ceaseless overcoming faced with absolute confusion (as many<br />

languages as there are subjects to speak) and the uncertain promise<br />

<strong>of</strong> absolute comprehension (one language for all subjects). Speaking<br />

is thus caught in the momentum that proceeds from an impossible<br />

origin to an event promised but not yet happened. Th is promise <strong>of</strong><br />

speech, this Versprechen has nothing to do with belief, with values,<br />

with an intention or a reference. It is speech itself, language itself,<br />

das Versprechen spricht, the promise speaking. And as Derrida says<br />

in Monolingualism <strong>of</strong> the Other, where I see a certain proximity<br />

to Rosenzweig, it is not possible to speak outside or without that<br />

promise.<br />

Language is, therefore, the rare singular power <strong>of</strong> aff ect and<br />

<strong>of</strong> time. It exceeds itself; it is not adequate to the beingness <strong>of</strong> its<br />

object, and even less to the being that it intends. Th is power is its<br />

impotence—or rather, simply the opposite: it does not know that

xviii • Foreword<br />

it is power-less to know, that it is the very fragility that gives it the<br />

power to say that it can not say, not what she can not say, but its very<br />

ineff ability. Language is self-transcendence par excellence.<br />

It is not that this dense intertwining does not produce a series<br />

<strong>of</strong> specifi c philosophical eff ects which the fi fth part <strong>of</strong> this book<br />

particularly echoes while refl ecting upon the link, knotted around<br />

the question <strong>of</strong> death that passes through so many developments <strong>of</strong><br />

Satya Das, between philosophy and what is named called here as the<br />

‘ethics <strong>of</strong> fi nitude’. It is possible, I think, to determine its fi gure while<br />

thinking <strong>of</strong> the Walter Benjamin’s Angel in Th eses on the Philosophy <strong>of</strong><br />

History. Th e Angel <strong>of</strong> History can’t be allowed to be pushed towards<br />

radiant tomorrows and toward a future where the mechanical storm<br />

<strong>of</strong> progress drives it. It neither can nor wants to leave without justice<br />

those who are dead and defeated, without providing them a redressal,<br />

whereas pure mechanical progress runs the risk <strong>of</strong> ignoring disasters<br />

and ruins for the sake <strong>of</strong> an end, a fi nality and a conclusion. Th e<br />

experience to come, the future happiness that is legitimate to wait<br />

for, therefore, must be based on the past failures. Th e past asserts its<br />

rights; the past, i.e., the dead who were the living. Benjamin links<br />

large chunks <strong>of</strong> historical time with contents that are not reducible<br />

to historical causality, to progress, to the concept, with experiences<br />

<strong>of</strong> suff ering, I would rather say with passions. In Benjamin, there is<br />

no passion for the past, in the sense <strong>of</strong> a backward looking pastism,<br />

a politics <strong>of</strong> nostalgia, but there is an ever passionate past, that is to<br />

say, never dead. As a result, the contents <strong>of</strong> the three dimensions<br />

<strong>of</strong> historical time are thereby distorted. Th e past can’t be reduced<br />

to the thought <strong>of</strong> its necessity. Th e present is not exhausted in the<br />

mere signifi cance <strong>of</strong> my full presence in this present. Th e future is<br />

not predetermined by historical reason. Th ese torsions are worked<br />

by a thought <strong>of</strong> the return <strong>of</strong> time upon itself, no doubt, but it does<br />

not correspond literally to the ‘abyssal thought’ <strong>of</strong> Zarathustra—<br />

but yet I see here somehow an echo, an attempt to speak in the<br />

somewhat unspeakable language <strong>of</strong> Nietzsche. Th is attempt stays<br />

close to the eternal return <strong>of</strong> the same. What Benjamin thinks<br />

and <strong>of</strong>f ers us to think is the tragedy <strong>of</strong> a past that is irremovable,<br />

surrounded by an absolute immutability or something that would<br />

never return to be identical to the same temporality. He comes up<br />

for and against Nietzsche, with something like a hope <strong>of</strong> the past,

Foreword • xix<br />

as much as a remembrance <strong>of</strong> the future. Th e weakness <strong>of</strong> the past<br />

waits for a possible rectifi cation, to come, promised by time. Th e<br />

present is thus never contemporary to itself, purely adequate to<br />

a full presence, heedless <strong>of</strong> the past and headed for the future. If<br />

all that happens happened in the pure present, time would never<br />

be a surprise, a grasping <strong>of</strong> the subject. But time is precisely this<br />

dispossession <strong>of</strong> mastery, the subject seized in the moment. Between<br />

the two allegories, namely the Angel <strong>of</strong> Benjamin, and Nietzsche’s<br />

Postern, there is a kind <strong>of</strong> repulsive affi nity, both challenging and<br />

diffi cult.<br />

It seems incontestable to me that the ethics <strong>of</strong> fi nitude according to<br />

Satya Das cannot be anything other than an ethics <strong>of</strong> the temporality<br />

and <strong>of</strong> the temporalization magnetized by the ever impossible<br />

fulguration <strong>of</strong> the ethical moment. I see in this one <strong>of</strong> the richest<br />

areas <strong>of</strong> this beautiful book and I hope it will have numerous and<br />

diverse readers.<br />

Gérard Bensussan<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Strasbourg

§ Premise<br />

Th is mortal called ‘man’ is an open existence, exposed to mortality and<br />

free towards the coming that is revealed to him in lightning fl ash. Free<br />

towards the ever new possibility <strong>of</strong> beginning, the mortal is endowed with<br />

the gift <strong>of</strong> time, as if an eternity that remains beyond his death, a time<br />

always ‘to come’. In this messianic remnant <strong>of</strong> time alone lies redemptive<br />

fulfi llment for the mortals—in the possibility <strong>of</strong> the ever new beginning<br />

in the time ‘to come’.<br />

It is this question <strong>of</strong> time to come, the affi rmation <strong>of</strong> a redemptive<br />

future that is pursued in this work. It occurs as and in a confi guration <strong>of</strong><br />

questions, which is not a system but rather, let’s say, a gesture or style <strong>of</strong><br />

pursuing a thought which is repetitively and, therefore, discontinuously<br />

seized as questions. Th ese are the questions <strong>of</strong> mortality and temporality,<br />

<strong>of</strong> the lightning fl ash <strong>of</strong> language that reveals man, beyond any predicative<br />

historical closure, his fi nitude and the Openness where man fi nds<br />

himself exposed to the event <strong>of</strong> coming, to the redemptive fulfi lment in this<br />

coming itself, which he anticipates in an existential attunement <strong>of</strong> hope.<br />

All these questions are introduced in the movement <strong>of</strong> confi guration, or<br />

constellation that affi rms the coming time, and feels the requirement <strong>of</strong><br />

redemption in hope, beyond all that is given to our historical existence.<br />

Th ese exercises <strong>of</strong> thinking are to be called: ‘confi guration thinking’.

Prologue

§ Th e <strong>Promise</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Time</strong><br />

To Come<br />

Th is is an attempt to elaborate upon the notion <strong>of</strong> coming time, the<br />

coming into existence, not what has come as ‘this’, or ‘that’, but the<br />

coming itself, the messianic promise <strong>of</strong> the redemptive arrival. In a<br />

phenomenological and deconstructive manner, which is a gesture<br />

<strong>of</strong> reading and seizing a truth rather than a method here, I will<br />

attempt to reveal the metaphysical foundation <strong>of</strong> what is meant in<br />

the dominant sense <strong>of</strong> ‘politics’, ‘history’, or even ‘logic’, to loosen<br />

this structure—<strong>of</strong> what Heidegger calls Abbau and Destruktion der<br />

Ontologie in Sein und Zeit—so that outside the closure <strong>of</strong> the Struktur<br />

to affi rm and to welcome the coming, the future Not Yet. Th is is a<br />

movement towards a messianic affi rmation that problematizes the<br />

dominant metaphysical determination <strong>of</strong> history whose immanence<br />

is guaranteed by an immanent self-grounding subject. Th is will<br />

be shown in the subtle, extremely complex connection between a<br />

certain metaphysical determination <strong>of</strong> history and the dominant<br />

determination <strong>of</strong> logic based upon predicative proposition. In so far<br />

as predicative proposition determines the truth on the basis <strong>of</strong> what is<br />

already revealed and opened history, understood speculatively, that is<br />

based upon predicative proposition cannot think <strong>of</strong> any event as event,<br />

this coming into existence itself as coming. Hence, the immemorial<br />

promise <strong>of</strong> the ‘time to come’, this gift <strong>of</strong> the taking place <strong>of</strong> time<br />

is always attempted to be closed in the immanence <strong>of</strong> self-presence<br />

that <strong>of</strong>ten assumes the form <strong>of</strong> a mythic foundation. If the task <strong>of</strong><br />

politics and history is to be thought in a more originary manner, and

6 • THE PROMISE OF TIME<br />

if politics and history is not to be mere reductive totalization <strong>of</strong> this<br />

promise in the name <strong>of</strong> the task <strong>of</strong> an immanent negativity (since it<br />

must already presuppose the originary promise <strong>of</strong> their redemptive<br />

fulfi lment), then it will be necessary here to think another notion<br />

<strong>of</strong> history and politics outside this given sense <strong>of</strong> these concepts that<br />

means, outside their ground in metaphysics—history that opens itself<br />

up to the intensity <strong>of</strong> the messianic fulfi lment, to the redemption <strong>of</strong><br />

the violence <strong>of</strong> history itself.<br />

What is to think ‘to come’, understood in the verbal resonance <strong>of</strong><br />

the infi nitive ‘to’? What does it mean ‘now’ or, what is this ‘now’?—<br />

to think this ‘to come’ again, to think <strong>of</strong> the promise and the gift<br />

<strong>of</strong> event, to think again the remnant <strong>of</strong> time after the end <strong>of</strong> time,<br />

after each end and after each completion, after each ‘after’, this hope<br />

for an infi nite after only because it is already an infi nite before? Is<br />

it necessary now, more than ever before and more than ever after,<br />

precisely here and now, with an urgency <strong>of</strong> the moment, which is<br />

also urgency <strong>of</strong> each moment and each place, to be borne with ‘the<br />

principle <strong>of</strong> hope’—as Ernst Bloch (1995) names this principle—<br />

till and beyond, till and after death when the large-scale devastation<br />

and devaluation <strong>of</strong> all values seemed to have been accomplished, and<br />

seem to be accomplishing all the time? What, whence, is the necessity<br />

<strong>of</strong> hope now when all hopes seemed to have vanished from life, and<br />

life appears now more unredeemed and damaged than ever before,<br />

and yet whose claim <strong>of</strong> redemption has remained, precisely because<br />

<strong>of</strong> its utter impoverishment, undiminished, whose distant light is not<br />

yet extinguished?<br />

The Claim <strong>of</strong> Redemption and<br />

the Question <strong>of</strong> History<br />

Th e question <strong>of</strong> ‘to come’ is essentially about the claim <strong>of</strong> redemption<br />

in our historical destinal existence which is heard in its utmost<br />

intensity and urgency when a certain metaphysical determination <strong>of</strong><br />

history seems to have come to its gathering force and to its exhaustion.<br />

As if now the claim <strong>of</strong> redemption must enter anew, if the above<br />

questions have still retained their sense today, into the thought <strong>of</strong><br />

death and exhaustion, outside any thanatology and outside ontology,<br />

and outside death’s service into the metaphysical foundation <strong>of</strong>

Th e <strong>Promise</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Time</strong> • 7<br />

politics and history, not to take side <strong>of</strong> death against life, nor to take<br />

side <strong>of</strong> life against death, but to take side <strong>of</strong> future, to take the side from<br />

future which is always coming. Th is necessity <strong>of</strong> an ‘after’ after every<br />

‘after’, this ‘not yet’ that must remain ‘not yet’ is a necessity <strong>of</strong> another<br />

faith, <strong>of</strong> another promise and another thought <strong>of</strong> revelation. Th is faith<br />

is the one that is not satisfi ed merely being attached as an appendix<br />

to reason, nor merely with positing another being as a transcendental<br />

object somewhere in a transcendental world beyond this ‘world’. It<br />

is, rather, a thought <strong>of</strong> promise in the not yet which is rescued from<br />

the womb <strong>of</strong> the damaged present; it is to gather together again those<br />

sparks after the vessel is broken once into thousand pieces.<br />

Th is thought <strong>of</strong> the affi rmative, which is perhaps the most<br />

urgent task <strong>of</strong> thinking that we call ‘philosophical’, demands that<br />

the metaphysical foundation <strong>of</strong> our history and politics be made<br />

manifest and un-worked so that thinking can inaugurate another<br />

history which is not satisfi ed merely with grasping what has happened<br />

on the basis <strong>of</strong> its apophansis, but one that ecstatically remains open<br />

to the immemorial and to the incalculable and the unconditional<br />

arrival. Th is is to envisage an ecstatic history without monuments<br />

or monumentality whose the historical task <strong>of</strong> inauguration must<br />

accompany the un-working <strong>of</strong> the closure <strong>of</strong> immanence <strong>of</strong> selfpresence.<br />

In this sense, this historical task <strong>of</strong> rescuing the redemptive<br />

possibility <strong>of</strong> the advent from any immanence <strong>of</strong> apophantic closure<br />

is inseparable from the question <strong>of</strong> the possibility <strong>of</strong> truth, truth<br />

that releases in philosophical contemplation that element <strong>of</strong> the<br />

immemorial from the violence <strong>of</strong> cognition.<br />

Truth beyond Cognition<br />

At stake in these labours <strong>of</strong> thought is an attempt <strong>of</strong> a discovery, or<br />

un-covery <strong>of</strong> the moments <strong>of</strong> the originary event <strong>of</strong> the historical<br />

when history itself makes momentary pauses. It is to welcome the<br />

event <strong>of</strong> history during those fl eeting moments <strong>of</strong> lightning fl ash<br />

that illumine the taking place <strong>of</strong> history itself as a phenomenon <strong>of</strong><br />

unapparent apparition that defi nes it as the phenomenality <strong>of</strong> any<br />

phenomenon par excellence. We are concerned here with this taking<br />

place <strong>of</strong> history itself and not what is ‘presently given’ within the realm<br />

<strong>of</strong> a given historical totality. Philosophical truth, if it does not have to

8 • THE PROMISE OF TIME<br />

be saturated with the knowledge <strong>of</strong> the phenomenon ‘presently given’,<br />

is only rescued truth, ‘wrested truth’. It is truth that momentarily<br />

advents in the midst <strong>of</strong> existence, like what Benjamin says <strong>of</strong> ‘pr<strong>of</strong>ane<br />

illumination’ that makes its sudden apparition felt when ‘dialectics<br />

comes to a standstill’ (Benjamin 2002, p. 10). Th is truth, in contrast<br />

to the categorical cognition <strong>of</strong> ‘given presences’, calls forth an entirely<br />

diff erent notion <strong>of</strong> temporality and historicality, an entirely diff erent<br />

notion <strong>of</strong> phenomenality: not the phenomenality that is categorically<br />

grasped in the apophantic judgement but a phenomenality when the<br />

unapparent in a lightning fl ash makes itself felt, that dispropriates us,<br />

that takes away from us the foundation <strong>of</strong> language and judgement<br />

and exposes us to the openness <strong>of</strong> time, opening to the immemorial<br />

and to the Not Yet. Th is open is not a topological or ontological site<br />

but the monstrous site <strong>of</strong> history where event arrives as an event, the<br />

coming comes into presence. Th is coming cannot be predicated on the<br />

basis <strong>of</strong> what has come, or what would come to pass by. It is a coming<br />

that moves history or better inaugurates history out <strong>of</strong> a fundamental<br />

fi nitude <strong>of</strong> our being.<br />

What, then, does it mean ‘to come’? Let’s say, ‘to come’ is the<br />

occurring <strong>of</strong> the truth <strong>of</strong> existence, the truth <strong>of</strong> the occurring <strong>of</strong><br />

existence, the truth <strong>of</strong> the occurring itself, or still better, the occurrence<br />

<strong>of</strong> truth itself. It is this occurring, this event before anything that has<br />

occurred is the true and genuine notion <strong>of</strong> the historical. In this sense<br />

truth is essentially historical, but more originally understood, no<br />

longer as that is assimilable to the periodic breaks belonging to the<br />

accumulative gathering <strong>of</strong> truth, but truth as this epochal break itself,<br />

which for that matter is to be thought as historical before history,<br />

before memory and before monumentality.<br />

Existence<br />

To come: it is in this infi nitive <strong>of</strong> the verbal lies the resonance <strong>of</strong><br />

existence, not as an accidental property <strong>of</strong> existence, but existence in<br />

its existential character in its ecstasy and exuberance <strong>of</strong> advent. In this<br />

sense, this infi nitive verbal character <strong>of</strong> existence is more originary<br />

than any categorical predication <strong>of</strong> existence as ‘given presence’.<br />

Th erefore Heidegger at the beginning <strong>of</strong> his Being and <strong>Time</strong> (1962)

Th e <strong>Promise</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Time</strong> • 9<br />

distinguishes the existential analytic <strong>of</strong> Dasein from the predicative,<br />

categorial grasp <strong>of</strong> ‘the given presence’ (Vorhandenheit) in so far as<br />

existence, in the infi nitive <strong>of</strong> its verbal resonance is open to its own<br />

coming to presence, which is at each moment irreducible to what is and<br />

what has become present as ‘given presence’, as ‘constant presence’.<br />

Th e infi nitude <strong>of</strong> the verbal resonance which is the existentiality<br />

<strong>of</strong> existence as such, therefore, lies in a more originary manner: in<br />

‘the there’ <strong>of</strong> the verbal, as ex-sistence, which means, its ecstatic<br />

exceeding <strong>of</strong> any ‘-sistence’. Existence is essentially excessive. Herein<br />

lies the transcendence <strong>of</strong> Dasein, the essential non-closure <strong>of</strong> Dasein,<br />

Dasein which is each time fi nite and mortal. Here, ‘to come’ is not one<br />

particular mode <strong>of</strong> the three modes <strong>of</strong> time, but a ‘to come’ which is at<br />

each time a ‘to come’ without which there is neither past, nor presence,<br />

nor future for Dasein. At each moment <strong>of</strong> existing, Dasein is to come to<br />

itself, is to come to presence, because at each moment <strong>of</strong> existing Dasein is<br />

fi nite and mortal in its innermost ground. Unlike the ‘entities presently<br />

given’ (Vorhandenheit), Dasein ex-sists ecstatically, i.e., as an opening<br />

to the coming whose facticity, its ‘the there’ (Da <strong>of</strong> Da-sein), must<br />

already always be manifested if there is to be predicative, categorical<br />

grasp <strong>of</strong> presently given entities. How then, or when its ‘Da’ appears<br />

itself as ‘Da’ to Dasein if not as that which not merely, unlike<br />

‘presently given entities’, is the apparition <strong>of</strong> the apparent, but <strong>of</strong> the<br />

unapparent in lightning fl ash <strong>of</strong> the immemorial? In his later works,<br />

Heidegger attempts to develop a ‘phenomenology <strong>of</strong> the unapparent’,<br />

a phenomenology that is more originary than the phenomenology<br />

<strong>of</strong> consciousness’ self-presence. Such a ‘phenomenology <strong>of</strong> the<br />

unapparent’ is concerned with phenomenon that, being more<br />

originary than ‘constant presence’ <strong>of</strong> given present, is the event <strong>of</strong><br />

being, the coming to presence, or rather, presencing <strong>of</strong> the presence <strong>of</strong><br />

being, which for that matter, cannot be thought within the reductive<br />

totalization <strong>of</strong> the dominant metaphysics which is the history <strong>of</strong><br />

being as presence. Th is presencing <strong>of</strong> presence or, coming to come: ‘the<br />

phenomenology <strong>of</strong> the unapparent’ precedes and is more originary<br />

than dialectical mediation, and is, in a certain sense, a tautology. Th e<br />

unapparent is the letting or giving (‘es gibt’) <strong>of</strong> Being—the open ‘Da’ <strong>of</strong><br />

Dasein—where the presencing presences. In his Zähringen seminar <strong>of</strong><br />

1973, Heidegger speaks <strong>of</strong> this ‘phenomenology <strong>of</strong> the unapparent’:

10 • THE PROMISE OF TIME<br />

What is to be thought is ’presencing namely presences’.<br />

A new diffi culty arises: this is clearly a tautology. Indeed! Th is is a<br />

genuine tautology: it names the same only once and indeed as itself.<br />

We are here in the domain <strong>of</strong> the unapparent: presencing itself<br />

presences.<br />

Th e name for what is addressed in this state <strong>of</strong> aff airs is: which is<br />

neither being nor simply being, but … :<br />

Presencing presences itself (Heidegger 2003, p.79)<br />

And little later, again,<br />

I name the thinking herein question tautological thinking. It is the<br />

primordial sense <strong>of</strong> phenomenology. Further, this kind <strong>of</strong> thinking<br />

is before any possible distinction between theory and praxis. To<br />

understand this, we need to learn to distinguish between path and<br />

method. In philosophy, there are only paths; in sciences, on the<br />

contrary, there are only methods, that is, modes <strong>of</strong> procedure.<br />

Th us understood, phenomenology is a path that leads away to come<br />

before… and it lets that before which it is led to show itself. Th is<br />

phenomenology is a phenomenology <strong>of</strong> the unapparent. (Heidegger<br />

2003, p. 80).<br />

What Heidegger calls ‘facticity’ <strong>of</strong> existence (<strong>of</strong> the ‘Da’ <strong>of</strong> Dasein) with<br />

which ‘the phenomenology <strong>of</strong> the unapparent’ is concerned, Schelling<br />

calls it ‘actuality’ which is ‘un-pre-thinkable’ (Unvordenkliche) that<br />

must already hold sway beforehand even in order for a ‘speculative<br />

judgement’ which Hegel elaborated dialectically speculatively in<br />

Phenomenology <strong>of</strong> Spirit (1998). In this way Schelling distinguishes the<br />

‘metaphysical empiricism’ <strong>of</strong> his positive philosophy from Hegelian<br />

speculative empiricism <strong>of</strong> negative philosophy (Schelling 2007a).<br />

While negative philosophy can only grasp in a categorial-predicative<br />

manner what is the result <strong>of</strong> a process by retrogressively recuperating<br />

what has become <strong>of</strong> it, Schelling seeks the beginning in the ‘un-prethinkable’<br />

actuality (the ‘Da’ <strong>of</strong> Dasein, the event <strong>of</strong> ex-sisting) which<br />

must already always manifest itself before thematizing, predicative,<br />

categorical cognition, opening thereby existence to its coming as it were<br />

for the fi rst time. Th e exposure to the immemorial is what Schelling

Th e <strong>Promise</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Time</strong> • 11<br />

calls ‘irreducible remainder’, a ‘not yet’ <strong>of</strong> a past, an irrecuperable past<br />

that continuously exposes existence to its inexhaustible outside, to its<br />

un-predicative past <strong>of</strong> promise. What renders existence an ‘irreducible<br />

remainder’—its originary non-closure is nothing but its inextricable<br />

mortality—its radical fi nitude that refuses to be lifted up unto<br />

thought completely. Th is fundamental incompletion <strong>of</strong> existence,<br />

its originary un-accomplishment and non-work refuses Hegelian<br />

Aufhebung, the consolation <strong>of</strong> the concept, and the concept’s false<br />

promise <strong>of</strong> infi nitude and Absolute. Th e coming is the advent <strong>of</strong> time<br />

itself cannot be thought within any reductive historical-metaphysical<br />

totalization, or within the immanence <strong>of</strong> a self-presencing Subject.<br />

It is the positive beyond any immanence <strong>of</strong> negativity. Such is the<br />

presencing <strong>of</strong> presence.<br />

So it is with Rosenzweig. If the concept, the Absolute Concept’s<br />

promise <strong>of</strong> infi nite and immortality is a false, vain consolation for the<br />

mortal beings, it is because philosophy, as the cognition <strong>of</strong> the All<br />

presupposes—at the same time denying this presupposition—that<br />

death is Nothing for the mortals if it cannot be made into work for the<br />

sake <strong>of</strong> the universal. In this way, the multiple singularities <strong>of</strong> mortal<br />

cries will not be heard in the universal pathos <strong>of</strong> the One Absolute,<br />

for Absolute can only be One and be One only. What would the<br />

value <strong>of</strong> a system be, a system <strong>of</strong> philosophy (for it is question <strong>of</strong> value<br />

and not <strong>of</strong> knowledge) for the mortal beings who are individuated<br />

and singularized by its mortality, and yet this morality is foreclosed<br />

in order to make possible <strong>of</strong> a system <strong>of</strong> categories? Since existence,<br />

which is fi nite and mortal, is not enclosed within any philosophical<br />

discourse <strong>of</strong> totality or is not consoled by the vain consolation <strong>of</strong><br />

the concept, existence is thereby granted the gift, in its mortality,<br />

<strong>of</strong> a time to come which Rosenzweig thinks in a messianic manner<br />

as ‘redemption’ that is beyond the concept and beyond any closure,<br />

which is an eternal remnant <strong>of</strong> time, or a time <strong>of</strong> remnant that is to<br />

arrive eternally. It is always to come because it is the event <strong>of</strong> coming<br />

itself.<br />

Schelling, Heidegger, and Rosenzweig—in their irreducibly<br />

singular manners—are thinkers <strong>of</strong> coming and <strong>of</strong> mortality, <strong>of</strong><br />

promise and <strong>of</strong> fi nitude, <strong>of</strong> future and <strong>of</strong> the gift. One can name<br />

them as ‘the thinkers <strong>of</strong> fi nitude’.

12 • THE PROMISE OF TIME<br />

Messianic<br />

Th e messianic affi rmation <strong>of</strong> the coming has nothing <strong>of</strong> the theological<br />

messianism about it, at least in the given recognizable form <strong>of</strong> a<br />

religious tradition. It is, to say with Jacques Derrida, a ‘messianicity<br />

without messianism’, a messianicity that affi rms unconditionally the<br />

promise <strong>of</strong> the other, or opens itself, outside totality or system, to<br />

this promise <strong>of</strong> the other who is always ‘to come’ in each hic et nunc.<br />

In his Monolingualism <strong>of</strong> the Other or Prosthesis <strong>of</strong> Origin, Derrida<br />

writes about the untotalizable promise <strong>of</strong> future and its prosthetic<br />

origin:<br />

But the fact that there is no necessarily determinate content in this<br />

promise <strong>of</strong> the other, and in the language <strong>of</strong> the other does not make any<br />

less indisputable its opening up <strong>of</strong> speech by something that resembles<br />

messianism, soteriology, or, eschatology. It is structural opening, the<br />

messianicity, without which messianism itself, in the strict or literal<br />

sense, would not be possible. Unless, perhaps, this originary promise<br />

without any proper content is, precisely, messianism. And unless all<br />

messianism demands for itself this rigorous and barren severity, this<br />

messianicity shorn <strong>of</strong> everything (Derrida 1998, p. 68).<br />

In so far as the task <strong>of</strong> thinking this messianic promise <strong>of</strong> the<br />

future demands that the reductive totalization <strong>of</strong> the dominant<br />

metaphysical tradition be opened up and radically put into question,<br />

this task itself is inseparably bound up with experience <strong>of</strong> mortality<br />

as mortality. Th is thinking itself, in this innermost manner, is fi nite<br />

and mortal. If the dominant metaphysics has made death into the<br />

service <strong>of</strong> the dialectical-universal history and made death to retain a<br />

mere sacrifi cial signifi cance, it has its supplement in the theologicopolitical<br />

totalization that has made death a work, a kind <strong>of</strong> production<br />

<strong>of</strong> death through calculative technological manner, that has made our<br />

politics and ethics bereft <strong>of</strong> the sense <strong>of</strong> future. Th is means that our<br />

notions <strong>of</strong> politics and history derive their metaphysical foundation from<br />

a certain tacit theological determination <strong>of</strong> death, i.e., the possibility <strong>of</strong><br />

foundation without any given foundation. Th is death does not know<br />

true mourning.<br />

All movement <strong>of</strong> totalization seeks to denude the future <strong>of</strong> its<br />

sense and to rob our mortality <strong>of</strong> its aff ection. It does not know

Th e <strong>Promise</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Time</strong> • 13<br />

true mourning, and knows not the movement <strong>of</strong> hope. In order to<br />

counter this movement <strong>of</strong> totalization that is permeating in all aspects<br />

<strong>of</strong> our lives to such an extent that such a totality today does not<br />

know any totality that has limits, territory or locality, it is necessary<br />

to introduce another movement—without thetic, positing dialectical<br />

violence <strong>of</strong> concept—the redemptive movement <strong>of</strong> unconditional<br />

promise and the gift <strong>of</strong> time where time itself times, or ‘presencing<br />

itself presences’, a promise <strong>of</strong> coming outside violence <strong>of</strong> immanence<br />

<strong>of</strong> self-consuming presences.<br />

To introduce this movement, that means to expose philosophical<br />

thinking to the non-conditional outside, to the promising remnant<br />

<strong>of</strong> time, is the highest task <strong>of</strong> thinking today. Th e task <strong>of</strong> thinking<br />

today, at the accomplishment <strong>of</strong> certain metaphysics, is no longer<br />

to constitute epochal historical totality that sublates historical<br />

violence into a form <strong>of</strong> reconciliation, as a kind <strong>of</strong> speculativetragic<br />

atonement. Th is reconciliatory movement <strong>of</strong> the speculativetragic-historical<br />

that founds epochal totality has lost its redemptive<br />

sense today, since this totalizing movement can begin and end its<br />

process only with pure, autochthonous, thetic positing that carries<br />

its violent character (<strong>of</strong> positing) right to the end in a manner <strong>of</strong><br />

circular re-appropriation. Th e task <strong>of</strong> thinking is no longer that<br />

<strong>of</strong> reconciliation, dialectically accomplished, which begins with<br />

the violence <strong>of</strong> pure positing that in order to reach beyond this<br />

violence, posits its other which—ins<strong>of</strong>ar as it is still positing—is once<br />

more mere conditioned, once more mere thetic, and so on and so<br />

forth. Th e circular movement <strong>of</strong> the positing never attains to the<br />

unconditional forgiveness beyond the violence <strong>of</strong> pure positing. It<br />

would be necessary to think <strong>of</strong> an originary, unconditional promise<br />

before any power <strong>of</strong> positing, a non-positing positive <strong>of</strong> coming, a<br />

promise <strong>of</strong> the unapparent presencing that itself presences, an ecstasy<br />

that ex-tatically escapes the circular re-appropriation <strong>of</strong> predicates<br />

and conditions. Th e tautological presencing presences or coming comes<br />

that no phenomenology or ontology <strong>of</strong> self-consciousness’ selfpresence<br />

attains, is essentially a phenomenology <strong>of</strong> promise. It is on the<br />

basis <strong>of</strong> this originary promise <strong>of</strong> a radical futurity which is not an<br />

apparition like other phenomenon, but that advents each time each<br />

hic et nunc, may there arrive an ‘unconditional forgiveness’ beyond<br />

any immanent result <strong>of</strong> a dialectical-tragic reconciliation.

14 • THE PROMISE OF TIME<br />

It is here that Derrida’s (2001) messianic thought <strong>of</strong> an<br />

‘unconditional forgiveness’, which is to be distinguished from any<br />

immanent result <strong>of</strong> a dialectical-tragic reconciliation, demands our<br />

careful attention. Th e ‘messianicity without messianism’ is to be<br />

connected with the possibility <strong>of</strong> an ‘unconditional forgiveness’ which<br />

demands another thinking <strong>of</strong> mortality itself, mortality whose refusal<br />

to work clamours for another inception rather than the dialectical. It<br />

is the demand <strong>of</strong> a redemptive forgiveness beyond reconciliation. Th e<br />

thinking <strong>of</strong> forgiveness and the messianic affi rmation <strong>of</strong> the coming must<br />

pass through an experience <strong>of</strong> non-condition, or mortality on the basis <strong>of</strong><br />

which the unapparent appears.<br />

The Lightning Flash <strong>of</strong> Language<br />

In what sense has the tragic-heroic pathos <strong>of</strong> reconciliation today<br />

lost its redemptive meaning if not in the sense that the immemorial<br />

promise and gift is only thought within the notion <strong>of</strong> an epochal<br />

totality? When the notion <strong>of</strong> promise is appropriated and is sought to<br />

be mastered by inscribing it into a categorical conceptual apparatus,<br />

then language—bereft <strong>of</strong> remembrance and promise—reifi es<br />

what has become <strong>of</strong> presence, ‘the given presence’, and forgets the<br />

immemorial promise given in the language <strong>of</strong> naming, in the dignity<br />

<strong>of</strong> the name. Th en the categorical task <strong>of</strong> cognition, its labour <strong>of</strong><br />

predication robs language its linguistic essence, that <strong>of</strong> welcoming<br />

the advent to arrive that lies outside the predicative proposition. Th e<br />

movement <strong>of</strong> confi guration that outside the cognitive categorical<br />

totality rescues the promise in saying and welcomes in a messianic<br />

hope the advent to come without violence is what Rosenzweig calls<br />

‘language-thinking’ (Rosenzweig 2000, pp. 109-139). What arrives<br />

in philosophical language, according to Rosenzweig, is not the<br />

universal essence <strong>of</strong> the One, but the linguistic essence <strong>of</strong> the fi nite<br />

singulars which is the multiple singulars’ exposure or abandonment<br />

to their singularly irreducible fi nitude. Th e linguistic essence <strong>of</strong> the<br />

fi nite beings, who are irreducibly multiple and singulars, is in this<br />

intrinsic intimacy with those beings’ pure exposure to their fi nitude.<br />

Similarly for Heidegger too, ‘the phenomenology <strong>of</strong> the<br />

unapparent’ has an essential relation to the naming the language <strong>of</strong><br />

man who is essentially this fi nite being. Th inking too, ins<strong>of</strong>ar it comes

Th e <strong>Promise</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Time</strong> • 15<br />

to us and that we never go to thinking and is a gift from a site wholly<br />

otherwise than man, arrives on the basis <strong>of</strong> our fi nitude that demands<br />

that it is to be thanked. Th e dignity and nobility <strong>of</strong> thinking lays in<br />

this recognition. With this thankfulness there is receptivity—in so<br />

far our fi nitude renders us, like an open wound, being receptive—<br />

welcoming the advent <strong>of</strong> coming, or to the presencing <strong>of</strong> the presence.<br />

Language, even before it is categorical cognition <strong>of</strong> ‘given presences’<br />

in apophansis, is the naming-saying that welcomes the unapparent<br />

apparition, i.e., the letting being as such to appear. With thankfulness<br />

and gratitude, mortals welcome the coming and receive the future.<br />

Th is promise <strong>of</strong> future is what the wanderer-thinker, in his path <strong>of</strong><br />

thinking, contemplates and is intimated at during sudden lightning<br />

fl ashes, for the advent <strong>of</strong> which he must be ready to take a leap,<br />

and open his soul to the future <strong>of</strong> thinking itself, without making a<br />

system out <strong>of</strong> it, without totalizing it. Language is this exposure, or<br />

this abandonment to the excessive light <strong>of</strong> the sudden apparition <strong>of</strong><br />

the otherwise that in the lucidity <strong>of</strong> the coming blinds him with its<br />

brilliancy.<br />

In traditional messianic religions, the coming <strong>of</strong> Messiah is<br />

something like violence. It is violence unlike any other violence,<br />

violence without the violence <strong>of</strong> law, <strong>of</strong> what Benjamin calls ‘divine<br />

violence’ as distinguished from law-positing and law-preserving<br />

violence. It is such a lightning fl ash that the poet Hölderlin speaks as<br />

the strike <strong>of</strong> Apollo: in relation to this momentary apparition <strong>of</strong> the<br />

unapparent, the poet-wanderer or the philosopher is always belated.<br />

Hence he must arrive beforehand, like the Nietzschean philosopher<br />

<strong>of</strong> heralding, announcing the unapparent apparition, implying the<br />

presencing that itself presences, the coming itself that comes, and not<br />

like the owl <strong>of</strong> Minerva taking its fl ight at the dusk <strong>of</strong> history.<br />

Wandering, Thinking<br />

In philosophy, there are only paths; in sciences, on the contrary, there<br />

are only methods, that is, modes <strong>of</strong> procedure.<br />

Heidegger (2003, p. 80)<br />

Th erefore, sonority or rhythm <strong>of</strong> wandering is caesural. One who has<br />

the experience <strong>of</strong> wandering in mountain paths knows the fragmented

16 • THE PROMISE OF TIME<br />

joining <strong>of</strong> those mountain paths. Th ese joints are co-junctions <strong>of</strong><br />

the disjointed without any prior principle. One may call such an<br />

experience a constellation or confi guration <strong>of</strong> thinking. Th e experience<br />

<strong>of</strong> wandering on the path <strong>of</strong> thinking refuses gathering, or collecting<br />

into unity, even if it is unity with diff erence. Th inking moves in<br />

pathways and not in methods, i.e., ‘modes <strong>of</strong> procedures’ (Ibid.). It<br />

is tempered with its own dispersal and fragmentation, and thereby<br />

refuses to have to do with the unity <strong>of</strong> a thesis. Th e temporality <strong>of</strong> the<br />

wandering is like relation to a time that has already happened, occurred<br />

to which it is joined as a heterogonous assemblage, a constellation <strong>of</strong><br />

paths, or a confi guration <strong>of</strong> discontinuous ways. What is to come must<br />

have happened, already always, at a moment <strong>of</strong> lucid darkness<br />

wherefrom time itself begins its journey, and spacing emerges. Th is is<br />

to say: ‘presencing itself presences’. Unlike the dialectical-speculative<br />

process <strong>of</strong> a history leading straight to the Absolute, wandering is not<br />

succession <strong>of</strong> instants though, because <strong>of</strong> his fi nitude and mortality,<br />

the wanderer relates to himself as a point in-between. To exist is to<br />

fi nd oneself in this in-between which is, for that matter, absence <strong>of</strong><br />

time’s presence and absence <strong>of</strong> space’s presence, the in-between that<br />

opens itself on both sides to the indefi nite, incalculable lengthening<br />

<strong>of</strong> time, as if time stretches out without beginning and without end.<br />

Th inking, philosophical thinking is this exposure to this time before<br />

time that advents as lightning fl ash where the immemorial presents<br />

itself as unapparent apparition.<br />

Th e wanderer-thinker therefore constantly exposes himself to his<br />

non-condition. It is in this sense that Heidegger speaks <strong>of</strong> Dasein as<br />

‘the placeholder <strong>of</strong> nothing’ (Heidegger 1998, p. 91), the placeholder<br />

<strong>of</strong> the ‘outside’. It is like the caesura <strong>of</strong> a resonance, which in resonating,<br />

inscribes an interval in the pathway <strong>of</strong> thinking. Th inking is this great<br />

caesural resonance that astonishes the wanderer-thinker as he moves<br />

along in the great winding paths <strong>of</strong> solitary mountains. Wandering,<br />

the poet-thinker makes the movement, the movement <strong>of</strong> infi nity<br />

outside the dialectical thesis and anti-thesis. Th erefore, wandering<br />

is non-dialectical movement par excellence. Th is wandering, which<br />

itself is caesural resonance, repeats itself and through this repetition<br />

brings something new that in its advent astonishes him, surprises<br />

him, throws him outside <strong>of</strong> himself, unto the open, unto that site<br />

<strong>of</strong> encounter with the advent. Repetition here never mimetically

Th e <strong>Promise</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Time</strong> • 17<br />

reproduces the same truth at a diff erent level but welcomes truth<br />

that each time suspends the law <strong>of</strong> the dialectical. Th inking, if it has<br />

to open itself in its ecstasy to the space <strong>of</strong> the outside where truth<br />

advents, this manifestation <strong>of</strong> the unapparent must have a diff erent<br />

logic than the logic <strong>of</strong> a scientifi c method.<br />

Configuration Saying<br />

Th erefore, the necessity: to repeat the truth <strong>of</strong> the advent, to repeat<br />

the advent <strong>of</strong> truth, repetitively, to be seized by the advent this is<br />

coming and always remaining to come. Th ere is always something like<br />

a universality <strong>of</strong> thinking, not the universality <strong>of</strong> the concept but the<br />

universality <strong>of</strong> the ‘singular each time’. Language <strong>of</strong> thinking bears this<br />

singularity <strong>of</strong> the universal through its multiple repetitions. Th e task,<br />

through this diff erential repetition, and universalizing the singular<br />

‘presencing <strong>of</strong> presence’, is to preserve each time anew the excess<br />

<strong>of</strong> this event <strong>of</strong> unapparent apparition without reducing it to any<br />

immanence <strong>of</strong> predicates and ‘presently given’ presents. Th erefore,<br />

there arises the necessity to say, again and again, each time anew,<br />

in the poetic naming-language <strong>of</strong> mortals that lets the unapparent<br />

appear, without reducing it to the universality <strong>of</strong> the categorical<br />

cognitive grasp. Since the advent <strong>of</strong> the coming in its momentary<br />

apparition discontinues, suspends, interrupts itself, it does not belong<br />

to any discourse <strong>of</strong> totality or system. It does not fi nd itself as to its<br />

own ground and condition. Such an advent that resonates in every<br />

poetical saying says the whole and yet remains outside <strong>of</strong> any totality.<br />

It is what the present writer shall call confi guration saying, which is<br />

not a method, for it does follow any ‘ism’ as such but a gesture, a<br />

sonority, a resonance <strong>of</strong> saying that says over and over again, which<br />

is at each moment fi nite and new, something that heralds rather than<br />

gives the result <strong>of</strong> a process in the form <strong>of</strong> predicative propositions.<br />

Th e confi guration saying is an attempt to think the whole without<br />

totality, repetition without recuperation, and universality without<br />

universalism. Each coming is a coming singularly universal, a coming<br />

itself which is promised as gift given to beings mortal and fi nite. It is<br />

a gift complete, a completed gift in itself and therefore there is in it a<br />

universality whose completeness completes our speech. Silence is the<br />

beatifi c recognition <strong>of</strong> this completeness <strong>of</strong> speech, a silence which is not

18 • THE PROMISE OF TIME<br />

defi ance nor recalcitrance <strong>of</strong> speech but the completeness <strong>of</strong> speech itself<br />

wherein consists the dignity <strong>of</strong> the language <strong>of</strong> the mortals. It is not<br />

the silence <strong>of</strong> the mythic-heroic tragic man as defi ance because he<br />

is superior to the God in his mortality, because <strong>of</strong> his capacity <strong>of</strong><br />

death can defy even the God. Th e ‘divine mourning’ that resonates in<br />

silence is the remembrance <strong>of</strong> the immemorial gift, remembrance <strong>of</strong><br />

the immemorial promise, that is, the promise <strong>of</strong> the unthought that<br />

is already always given to man as a gift. Th erefore, in silence language<br />

itself, at its limit, as it were mourns, or mournfully remembers the<br />

immemorial promise, because it fails itself to name the name. Th ere<br />

is, therefore, always certain mournfulness in silence and a silence in<br />

mournfulness, which is distinguished from the silence <strong>of</strong> the tragicmythic<br />

heroic man who asserts at the face <strong>of</strong> his own death his<br />

solitude and his self denuded <strong>of</strong> contingent features <strong>of</strong> his character. 1<br />

What follow in the following pages are confi guring <strong>of</strong> sayings<br />

<strong>of</strong> what the wanderer-thinker is exposed, in his path <strong>of</strong> wandering,<br />

to the appearing <strong>of</strong> unapparent, the coming itself. What kind <strong>of</strong><br />

appearing is this which is appearing <strong>of</strong> the unapparent? What kind <strong>of</strong><br />

phenomenon is this whose phenomenality lies in its un-apparition?<br />

What is this coming, which is not any ‘this’ or ‘that’ coming, which is<br />

not exhausted in anything that has come to pass, that has appeared<br />

to disappear and that has become a phenomenon so that it no longer<br />

appears to us anymore? Is there a coming that is the appearing <strong>of</strong><br />

the non-apparent and phenomena <strong>of</strong> the non-phenomenal? Th e<br />

wandering the poet-thinker, wandering in his solitary winding path<br />

<strong>of</strong> a mountain, is seized by the perplexity, or aporia <strong>of</strong> this question.<br />

If there is an essential thinking, or if thinking is to attain the essential,<br />

then thinking must not shy away from this aporia, but rather must<br />

allow this aporia to move thinking itself and in this pathway <strong>of</strong><br />

thinking, attain the essential. All philosophical thinking is essentially<br />

fi nite and incomplete. Out <strong>of</strong> this essential incompleteness, the poetthinker<br />

repeats himself here and there, as the wanderer must renew<br />

his leaps, because repetition always arises out <strong>of</strong> an essential fi nitude<br />

<strong>of</strong> thinking itself.<br />

What is presented in this work is nothing but the ‘wrested truth’,<br />

spoken in a confi guration that emerges out <strong>of</strong> the experiences <strong>of</strong><br />

wandering. Th erefore, no claim here been made that the truth is to<br />

be presented as completed truth. Once such a claim is made, the

Th e <strong>Promise</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Time</strong> • 19<br />

truth no longer remains the truth but becomes an imbecile, castrated<br />

cognition <strong>of</strong> given phenomenon commensurable with a settled mode<br />

<strong>of</strong> existence. Truth is only to be wrested, seized in its movement, in its<br />

becoming by going under, in its point <strong>of</strong> beginning or starting, but not at<br />

the moment <strong>of</strong> settled result. Th at, however, does not mean that truth<br />

in itself is always incomplete, but only the claim <strong>of</strong> saying the truth—<br />

because <strong>of</strong> the fi nitude <strong>of</strong> the mortal—in its absolute completeness<br />

remains only a false claim. Truth in its absolute presentation and<br />

arrival as an event is the destruction <strong>of</strong> a language. It ruins language<br />

and abandons it to fainting murmur, or to the lament <strong>of</strong> music.<br />

Th erefore, the attempt to say ‘the wrested truth’ can only be a<br />

regulated form <strong>of</strong> divine madness which must constantly be solicited<br />

to. Th ere is always the possibility, not merely by going astray, but <strong>of</strong><br />

madness itself as far as truth is never <strong>of</strong> settled mode <strong>of</strong> cognition but<br />

that which when once seizes the philosopher, it makes him into what<br />

Plato calls a ‘horsefl y’.<br />

Truth in itself is never only a totality <strong>of</strong> the successive moments <strong>of</strong><br />

gradated cognition. In other words, there is no method in philosophy<br />

but only constellation <strong>of</strong> paths. Constellation is an assemblage but<br />

never a totality, a whole that makes sudden, momentary appearance<br />

that in its lightning fl ash seizes the thinker. It is only on the basis <strong>of</strong><br />

this prior seizure, the thinker can seize and wrest truth, for truth is<br />

not property <strong>of</strong> the mortal called ‘man’ but man belongs to truth, is<br />

claimed by truth and makes him fi rst <strong>of</strong> all what he is, the one who<br />

seizes and wrests truth from the immemorial that founds him and<br />

dispropriates him in advance. Th is is the promise <strong>of</strong> thought itself,<br />

ins<strong>of</strong>ar as—to speak with Heidegger—‘we never go to thinking,<br />

thinking comes to us’ (Heidegger 2001, p.6), in its sudden advent,<br />

like a lightning fl ash.

§ Radical Finitude<br />

If the emergence <strong>of</strong> modern philosophy is marked by the<br />

materialization <strong>of</strong> the question <strong>of</strong> fi nitude (once it becomes the<br />

matter <strong>of</strong> recounting the genesis and structure <strong>of</strong> subjectivity that<br />

has to emerge without any given ground, since no condition is given<br />

in the form <strong>of</strong> ‘substance’) that is because this fi nitude is essentially<br />

that <strong>of</strong> the question <strong>of</strong> the subject. Th e question <strong>of</strong> the subject in its<br />

fi nitude becomes the question <strong>of</strong> modernity and its determination <strong>of</strong><br />

historical breaks belonging to the accumulative movement <strong>of</strong> history<br />

itself. In Hegel’s case, therefore, the destinal question <strong>of</strong> history as<br />

he recounts in Phenomenology <strong>of</strong> Spirit becomes the metaphysical<br />

question <strong>of</strong> the subject whose fi nitude is grasped as the labour <strong>of</strong><br />

negativity. At the limit <strong>of</strong> this metaphysics <strong>of</strong> history, when the whole<br />

history <strong>of</strong> that metaphysics <strong>of</strong> subjectivity comes to a ‘standstill’ (in<br />

the sense <strong>of</strong> what Benjamin calls ‘dialectics at a standstill’), it reveals<br />

itself to be that where the claim <strong>of</strong> redemption is not fulfi lled. It<br />

then becomes necessary to think <strong>of</strong> a radical notion <strong>of</strong> fi nitude as<br />

the task <strong>of</strong> inaugurating another thought <strong>of</strong> history which should at<br />

the same time articulate a radical critique <strong>of</strong> the violence <strong>of</strong> history.<br />

Th e notion <strong>of</strong> history is bound with the question <strong>of</strong> fi nitude where<br />

fi nitude is seen less as a labour <strong>of</strong> negativity but as a gift on the basis<br />

<strong>of</strong> which mortals are placed in the open site <strong>of</strong> the inauguration <strong>of</strong><br />

history itself.<br />

The Immemorial<br />

What would our existence be if its days and months and years are to<br />

pass away in monotonous succession like the Hegelian ‘homogenous

Radical Finitude • 21<br />

succession <strong>of</strong> empty instants’ (Benjamin 1977, pp. 251-261) which,<br />

like the leaves <strong>of</strong> trees, appear in Spring only to disappear in Autumn<br />

and return in Spring, or like the infi nite nameless waves <strong>of</strong> the Sea—<br />

without hope, meaning and promise—bringing to us nothing but the<br />

eternal murmur <strong>of</strong> what is already become fi nished, accomplished,<br />

when each moment is like any other moments, an eternal Now, like<br />

the eternal Now <strong>of</strong> the waves, if there is no ‘not yet’ to become, no<br />

‘not yet’ to come, and no hope for the ‘not yet’ to accomplish? If the<br />

great Hegelian dialectical-historical time is none but this eternally<br />

un-redemptive, eternally boring return to the same, without any<br />

ecstatic outside, without the redemptive advent <strong>of</strong> future outside,<br />

then how despairing and desolate our existence would be? What<br />