A quArterly mAgAzine of Art And culture issue 7 ... - Visual Studies

A quArterly mAgAzine of Art And culture issue 7 ... - Visual Studies

A quArterly mAgAzine of Art And culture issue 7 ... - Visual Studies

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

CABINET<br />

A <strong>qu<strong>Art</strong>erly</strong> <strong>mAgAzine</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>And</strong> <strong>culture</strong><br />

<strong>issue</strong> 7 summer 2002<br />

us $8 cAnAdA $13 uK £6

cabinet<br />

Immaterial Incorporated<br />

181 Wyck<strong>of</strong>f Street Brooklyn NY 11217 USA<br />

tel + 1 718 222 8434<br />

fax + 1 718 222 3700<br />

email cabinet@immaterial.net<br />

www.immaterial.net<br />

Editor-in-chief Sina Najafi<br />

Senior editor Brian Conley<br />

Editors Jeffrey Kastner, Frances Richard, David Serlin, Gregory Williams<br />

<strong>Art</strong> directors (Cabinet Magazine) Ariel Apte and Sarah Gephart <strong>of</strong> mgmt.<br />

<strong>Art</strong> director (Immaterial Incorporated) Richard Massey/OIG<br />

Editors-at-large Saul Anton, Mats Bigert, Jesse Lerner, Allen S. Weiss,<br />

Jay Worthington<br />

Website Krist<strong>of</strong>er Widholm and Luke Murphy<br />

Image editor Naomi Ben-Shahar<br />

Production manager Sarah Crowner<br />

Development director Alex Villari<br />

Contributing editors Joe Amrhein, Molly Bleiden, Eric Bunge,<br />

<strong>And</strong>rea Codrington, Christoph Cox, Cletus Dalglish-Schommer, Pip Day,<br />

Carl Michael von Hausswolff, Srdjan Jovanovic Weiss, Dejan Krsic,<br />

Tan Lin, Roxana Marcoci, Ricardo de Oliveira, Phillip Scher, Rachel Schreiber,<br />

Lytle Shaw, Debra Singer, Cecilia Sjöholm, Sven-Olov Wallenstein<br />

Editorial assistant James Pollack<br />

Pro<strong>of</strong>readers Joelle Hann & Catherine Lowe<br />

Assistants Amoreen Armetta, Emelie Bornhager, Ernest Loesser,<br />

Normandy Sherwood<br />

Prepress Zvi @ Digital Ink<br />

Founding editors Brian Conley and Sina Najafi<br />

Printed in Belgium by Die Keure<br />

Cabinet (ISSN 1531-1430) is a quarterly magazine published by Immaterial<br />

Incorporated. Periodicals Postage paid at Brooklyn NY.<br />

Postmaster: Send address changes to Cabinet, 181 Wyck<strong>of</strong>f Street, Brooklyn,<br />

NY 11217<br />

Immaterial Incorporated is a non-pr<strong>of</strong>it 501 (c) (3) art and <strong>culture</strong> organization<br />

incorporated in New York State. Cabinet is in part supported by generous grants<br />

from the Flora Family Foundation, the New York State Council on the <strong>Art</strong>s, the<br />

Frankel Foundation, and by donations from individual patrons <strong>of</strong><br />

the arts. Contributions to Immaterial Incorporated and Cabinet magazine are<br />

fully tax-deductible.<br />

Subscriptions<br />

Individual one-year subscriptions (in US Dollars): United States $24,<br />

Europe and Canada $34, Mexico $50, Other $60<br />

Institutional one-year subscriptions (in US Dollars): United States $30,<br />

Europe and Canada $42, Mexico $60, Other $75<br />

Please either send a check in US dollars made out to “Cabinet,” OR send,<br />

fax, or email us your Visa /Mastercard information. To process your credit card,<br />

we need your name, card number, expiry date, and billing address. You can also<br />

subscribe directly on our website at www.immaterial.net/cabinet with a credit<br />

card. Back <strong>issue</strong>s available in the US for $8 and in Europe, Canada, and Mexico<br />

for $13. Institutions can also subscribe through EBSCO and Swets Blackwell.<br />

Advertising<br />

Email advertising@immaterial.net or call + 1 718 222 8434.<br />

Distribution<br />

US and Canada: Big Top Newstand Services, a division <strong>of</strong> the IPA.<br />

For more information, call + 1 415 643 0161, fax + 1 415 643 2983,<br />

or email info@BigTopPubs.com.<br />

Europe: Central Books, London. Email: orders@centralbooks.com<br />

Cabinet is also available through Tower stores around the world.<br />

Please send distribution questions to distribution@immaterial.net<br />

Cabinet eagerly accepts unsolicited manuscripts, preferably sent by e-mail<br />

to proposals@immaterial.net as a Micros<strong>of</strong>t Word document or in Rich Text<br />

Format. Hard copies should be double-spaced and in duplicate. We can only<br />

return manuscripts if a self-addressed, stamped envelope is provided. We do<br />

not publish poetry. Please contact us for guidelines for submitting artworks.<br />

Contents © 2002 Immaterial Incorporated & the authors, artists, translators.<br />

All rights reserved. Unauthorized reproduction <strong>of</strong> any material here is a no-no.<br />

The views published in this magazine are not necessarily those <strong>of</strong> the writers,<br />

let alone the spineless editors <strong>of</strong> Cabinet.<br />

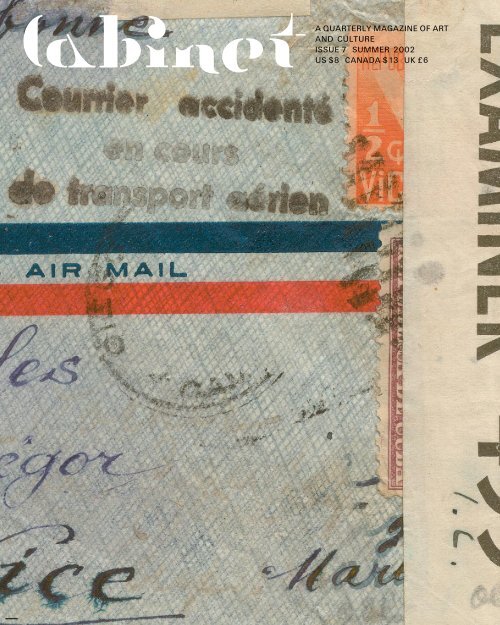

cover: envelope recovered from the crash <strong>of</strong> the Pan American World<br />

Airways plane “Yankee Clipper” in Lisbon on February 22, 1943. Courtesy<br />

Kendall Sanford

Contributors<br />

Magnus Bärtås is an artist and writer based in Stockholm. In 2000, he<br />

published a collection <strong>of</strong> essays Orienterarsjukan och andra berättelser<br />

(together with Fredrik Ekman). His recent exhibitions “Satellites” and “The<br />

Museum <strong>of</strong> Homeless Ideas” were shown at Roger Björkholmen Gallery in<br />

Stockholm and OK Gallery in Rijeka, Croatia (together with Zdenko Buzek).<br />

Mike Ballou is an artist based in Brooklyn, New York.<br />

M. Behrens (born 1970 in Germany) has lived and worked internationally as<br />

an artist and designer in Frankfurt since 1991. Since 1996 he has worked<br />

mainly with sound and video installations.<br />

David Brody is an artist who lives and works near the Kool Man depot in Brooklyn.<br />

Matthew Buckingham is an artist based in New York. He is represented by<br />

Murray Guy Gallery, New York, and Galleri Tommy Lund, Copenhagen.<br />

Brian Burke-Gaffney was born in Canada in 1950 and came to Japan in 1972.<br />

He has been pr<strong>of</strong>essor at the Nagasaki Institute <strong>of</strong> Applied Science since 1996.<br />

Paul Collins edits the Collins Library for McSweeney’s Books, and is the<br />

author <strong>of</strong> Banvard’s Folly (Picador: 2001) and the forthcoming travelogue-memoir<br />

Sixpence House (Bloomsbury USA). He lives in Portland, Oregon.<br />

Nancy Davenport is a New York-based artist represented by Nicole Klagsburn<br />

Gallery. Her work has been exhibited recently at the Rockford Museum in<br />

Illinois and at the 25th São Paulo Biennial.<br />

<strong>And</strong>rew Deutsch is a sound/video artist who lives in Hornell, NY, and teaches<br />

sound art at Alfred University. He is a member <strong>of</strong> the Institute for Electronic <strong>Art</strong><br />

at Alfred University and <strong>of</strong> the Pauline Oliveros Foundation’s board <strong>of</strong> directors.<br />

Jon Dryden is a musician and writer living in Brooklyn, New York.<br />

Elizabeth Esch is completing a dissertation in the Department <strong>of</strong> History at New<br />

York University.<br />

Matt Freedman is an artist and writer living in Brooklyn.<br />

Dr. Merrill Garnett is a cancer researcher and the founder and CEO <strong>of</strong> Garnett<br />

McKeen Laboratory, Inc. Dr. Garnett has had research laboratories at the<br />

Central Islip State Hospital, Waldemar Medical Research Foundation,<br />

Northport Veterans’ Administration Medical Center, and the High Technology<br />

Incubator <strong>of</strong> The State University <strong>of</strong> New York at Stony Brook.<br />

Tim Griffin is a writer, curator, and art editor <strong>of</strong> Time Out New York. His book<br />

<strong>of</strong> essays titled Contamination, a collaborative project with artist Peter Halley,<br />

is forthcoming from Gabrius (Milan) in September. His book <strong>of</strong> poetry, July in<br />

Stereo, is forthcoming from Shark Press (New York).<br />

Daniel Harris is the author <strong>of</strong> A Memoir <strong>of</strong> No One In Particular (Basic Books,<br />

2002). He has also written The Rise and Fall <strong>of</strong> Gay Culture and Cute, Quaint,<br />

Hungry, and Romantic: The Aesthetics <strong>of</strong> Consumerism.<br />

David Hawkes teaches at a university in Pennsylvania. He is the author <strong>of</strong><br />

Ideology (Routledge, 1996) and Idols <strong>of</strong> the Marketplace (Palgrave, 2001), and<br />

his work has recently appeared in The Nation, The Times Literary Supplement<br />

and The Journal <strong>of</strong> the History <strong>of</strong> Ideas.<br />

Sharon Hayes is an artist. She is currently an MFA candidate in the Interdisciplinary<br />

Studio at UCLA’s Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>.<br />

Brooklyn-based soundmaker Douglas Henderson has been working with<br />

electro-acoustic composition, music for dance, and installation pieces for 20<br />

years. He has run the Sound <strong>Art</strong>s program at the Museum School, Boston<br />

and holds a doctorate in composition from Princeton University. He can be<br />

reached through www.heartpunch.com.<br />

Bill Jones is an artist and writer. He is represented by the Sandra Gering Gallery in<br />

NY and is currently the Director <strong>of</strong> Operations <strong>of</strong> Garnett McKeen Laboratory, Inc.<br />

Jeffrey Kastner is a New York-based writer and an editor <strong>of</strong> Cabinet.<br />

Kris Lee and Matt Freedman met at the 1985 NCAA diving championships.<br />

They later discovered that they were distantly related.<br />

Nina Katchadourian is an artist who lives in Brooklyn and teaches at Brown<br />

University. She exhibits with Debs & Co in New York and with Catharine Clark<br />

Gallery in San Francisco.<br />

Emma Kay lives and works in London. She has exhibited widely in Europe and<br />

the US. She recently participated in the 2002 Sydney Biennial and has<br />

forthcoming exhibitions at The Approach, London, the Muscarnok Kunsthalle,<br />

Budapest, and Tate Modern, London. She has published an artist’s book,<br />

Worldview (Bookworks).<br />

Peter Lew is a New York-based artist whose work includes painting, installation<br />

and sound art. He has participated in the radio project WAR!, the sound<br />

show constriction at Pierogi gallery, and his paintings were included in Working<br />

in Brooklyn at the Brooklyn Museum. His work has been exhibited in Austria,<br />

Switzerland, and Japan.<br />

Dirk Libeer remembers Danny from when he was a boy.<br />

Paul Lukas, author <strong>of</strong> Inconspicuous Consumption: An Obsessive Look at the<br />

Stuff We Take for Granted and editor <strong>of</strong> Beer Frame: The Journal <strong>of</strong> Inconspicuous<br />

Consumption, is a Brooklyn-based writer who specializes in minutiae fetishism.<br />

His favorite color is green and his favorite state is Wisconsin.<br />

Christ<strong>of</strong> Migone is a multidisciplinary artist and writer. He lives and works in<br />

Montreal and New York.<br />

Susette Min is currently a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow at Pomona College.<br />

She is also an indepedent curator and most recently curated Rina Banerjee in<br />

a show entitled “Phantasmal Pharmacopia.” She lives in Los Angeles.<br />

Sina Najafi is editor-in-chief <strong>of</strong> Cabinet magazine.<br />

Pauline Oliveros (born 1932) is a composer living in Kingston, NY, and teaching<br />

at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Mills College, and Bard College. She is<br />

president <strong>of</strong> Pauline Oliveros Foundation, a creative cultural center in Kingston<br />

(http://www.deeplistening.org/pauline)<br />

Amy Jean Porter is an artist who recently moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts.<br />

Scott A. Sandage is Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor in the Department <strong>of</strong> History at Carnegie<br />

Mellon University. His book Forgotten Men: Failure in American<br />

Culture, 1819-1893 is forthcoming from Harvard University Press.<br />

Kendall C. Sanford is retired after working forty years in the airline industry and<br />

lives in Geneva. He has collected airmail historical material and air crash covers<br />

for nearly as long. He is a past president <strong>of</strong> the American Air Mail Society, the<br />

world’s largest aerophilatelic society.<br />

Peter Santino was born in Kansas in 1948.<br />

Paul Schmelzer lives in Minneapolis and writes on art and activism for<br />

publications including Adbusters, The Progressive, and Raw Vision.<br />

Tobias Schmitt. 1975: born in Frankfurt; 1989: first experiments with<br />

electronic music; 1994: started working as sbc; 1996: started doing artworks<br />

as Mischstab; 1999: founded Acrylnimbus.<br />

David Serlin is an editor and columnist for Cabinet. He is the co-editor <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>ificial<br />

Parts, Practical Lives: Modern Histories <strong>of</strong> Prosthetics (NYU Press, 2002).<br />

Lytle Shaw’s most recent poetry book is The Lobe (Ro<strong>of</strong>, 2002). He co-edits<br />

Shark magazine and curates the Line Reading Series at The Drawing Center.<br />

Michael Smith is an artist based in New York.<br />

Nedko Solakov is a Bulgarian artist living and working in S<strong>of</strong>ia. His work has<br />

been exhibited in many venues, including the 48th and 49th Venice Biennials,<br />

the 3rd and 4th Istanbul Biennials, the 1994 São Paulo Biennial, and Manifesta<br />

1. The series from which his Cabinet contribution is drawn was first presented<br />

at Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Berlin, in May 2002 and will then travel to the<br />

Ulmer Museum, Ulm, and Reina S<strong>of</strong>ia, Madrid.<br />

Yasunao Tone is a co-founder <strong>of</strong> Group Ongaku and an original member <strong>of</strong><br />

Fluxus. Born in Tokyo in 1935, he has resided in New York since 1972.<br />

He has exhibited in numerous shows, including the 1990 Venice Biennial and<br />

the 2001 Yokohama Triennial.<br />

Tom Vanderbilt lives in Brooklyn and is the author <strong>of</strong> Survival City: Adventures<br />

Among the Ruins <strong>of</strong> Atomic America (Princeton Architectural Press).<br />

Claude Wampler is an artist based in New York City.<br />

Allen S. Weiss has been working hard on ingestion: He recently co-edited<br />

French Food (Routledge), and his Feast and Folly is forthcoming (SUNY).<br />

Gregory Whitehead is the author <strong>of</strong> numerous broadcast essays and earplays,<br />

and is presently at work on a new play, Resurrection Ranch.<br />

Gregory Williams is a critic and art historian living in New York City. He is also an<br />

editor <strong>of</strong> Cabinet.<br />

David Womack was a Darmasiswa scholar in Indonesian literature and Javanese<br />

language at the Universitas Gadjah Mada in Yogyakarta, Java.<br />

He is currently the Director <strong>of</strong> New Media at the American Institute <strong>of</strong><br />

Graphic <strong>Art</strong>s.

Columns<br />

main<br />

failure<br />

and<br />

13<br />

17<br />

17<br />

19<br />

23<br />

30<br />

33<br />

36<br />

40<br />

44<br />

47<br />

51<br />

53<br />

58<br />

62<br />

66<br />

69<br />

70<br />

73<br />

76<br />

81<br />

85<br />

88<br />

90<br />

94<br />

96<br />

98<br />

102<br />

106<br />

108<br />

110<br />

113<br />

118<br />

122<br />

124<br />

126<br />

128<br />

the Clean room DaviD serlin<br />

leftovers Paul lukas<br />

Colors Tim Griffin<br />

ingestion allen s. Weiss<br />

ernst haeCkel and the miCrobial baroque<br />

DaviD BroDy<br />

field traCes Bill Jones<br />

mm, mm, good: marketing and regression in<br />

aesthetiC taste DaviD HaWkes<br />

beautiful indonesia (in miniature) DaviD Womack<br />

Paint and Paint names Daniel Harris<br />

things fall aPart: an interview with<br />

george sCherer Jeffrey kasTner<br />

the six grandfathers, Paha saPa,<br />

in the Year 502,002 C.e. maTTHeW BuckinGHam<br />

interPretations <strong>of</strong> the national Park serviCe<br />

sHaron Hayes<br />

soothe oPerator: muzak and modern sound art<br />

suseTTe min<br />

birds <strong>of</strong> north ameriCa sing hiP-hoP and<br />

sometimes Pause for refleCtion amy Jean PorTer<br />

hungrY for god GreGory WHiTeHeaD<br />

not Your name, mine Paul scHmelzer<br />

the bible from memorY emma kay<br />

blaCk box Tom vanDerBilT<br />

Crash Covers Jeffrey kasTner<br />

“shades <strong>of</strong> tarzan!”: ford on the amazon<br />

elizaBeTH escH<br />

hashima: the ghost island Brian Burke-Gaffney<br />

the floating island Paul collins<br />

old rags, some grand scoTT a. sanDaGe<br />

the war <strong>of</strong> the flea marvin Doyle<br />

the short, sad life <strong>of</strong> dannY the dragon Dirk liBeer<br />

better luCk next time GreGory Williams<br />

the disaPPointed and the <strong>of</strong>fended maGnus BärTås<br />

the invention <strong>of</strong> failure: an interview with<br />

sCott a. sandage sina naJafi & DaviD serlin<br />

travelfest is Closed micHael smiTH & naTHan HeiGes<br />

sYntax error: sPeCial Cd insert<br />

in Case <strong>of</strong> moon disaster William safire<br />

romantiC landsCaPes with missing Parts<br />

neDko solakov<br />

the life <strong>of</strong> ernst moiré lyTle sHaW<br />

ConCert nancy DavenPorT<br />

a/C cHeaTer.com<br />

orPhan nina kaTcHaDourian<br />

unlimited edition kris lee<br />

stoCk in failure institute PeTer sanTino

columns

“The Clean Room,” David Serlin’s column on science and<br />

technology, appears in each <strong>issue</strong> <strong>of</strong> Cabinet / “Leftovers” is<br />

a column in which Cabinet invites a guest to discuss leftovers<br />

or detritus from a cultural perspective / “Colors” is a column<br />

in which a guest writer is asked to respond to a specific color<br />

assigned by the editors <strong>of</strong> Cabinet / “Ingestion” is a column by<br />

Allen S. Weiss on cuisine, aesthetics, and philosophy<br />

the clean room / the new Face<br />

oF terrorism<br />

DaviD Serlin<br />

In the winter <strong>of</strong> 2002, the US Food and Drug Administration<br />

approved the use <strong>of</strong> Clostridium botulinum, a highly toxic<br />

microorganism, for medical use. In large, unsupervised<br />

doses, the bacterium taints organic products like meat,<br />

resulting in <strong>of</strong>ten-fatal cases <strong>of</strong> botulism or food poisoning.<br />

In small, controlled doses, the bacterium produces a<br />

paralyzing effect on nerve endings. Like anti-depressant<br />

medications such as Prozac, C. botulinum blocks the release<br />

<strong>of</strong> neural signals that transmit information to various<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> the body. For some physicians, the federal stamp<br />

<strong>of</strong> approval on Type A C. botulinum – otherwise known as<br />

Botox—means that patients suffering from cerebral palsy,<br />

blepharoplasm (eyelid muscle spasms), and other neuromuscular<br />

disorders will have much easier access to this<br />

medication.<br />

For many more physicians, however, the governmentapproved<br />

mass production and widespread availability <strong>of</strong><br />

Botox means a surplus <strong>of</strong> cold, hard cash. In elite consumer<br />

circles, the tiny bacterium has beckoned hither with one<br />

seductive promise: a single Botox injection paralyzes the<br />

nerve endings in an individual’s forehead muscles for up to<br />

three months. A middle-aged matron seeking to restore the<br />

smooth, wrinkle-free countenance <strong>of</strong> youth can undergo<br />

as many injections as her forehead (and bank account) can<br />

endure. Among the latest cosmetic possibilities for Botox are<br />

direct injections into the armpit to paralyze the sweat glands<br />

and render them moisture-free, a procedure whose effects<br />

can last for as long as half a year. Recent figures reveal that<br />

in 2001, physicians delivered over one million Botox injections,<br />

and the popularity <strong>of</strong> the procedure is expected to<br />

increase tenfold over the next few years. In response to<br />

consumer demand, Allergen, the main bio-medical supplier<br />

<strong>of</strong> Botox, is working with recombinant DNA technology to<br />

produce strains <strong>of</strong> C. botulinum that will double or triple the<br />

bacterium’s potency, thereby increasing its appeal for both<br />

new and longtime users.<br />

Not since the successful Dannon campaigns <strong>of</strong> the 1970s,<br />

featuring hardy Eastern European octogenarians wrapped<br />

in furs and babushkas extolling the virtues <strong>of</strong> eating yogurt<br />

for breakfast, have Americans so enthusiastically embraced<br />

the idea <strong>of</strong> putting active bacterial <strong>culture</strong>s into their bodies.<br />

Historically, individuals exposed to bacterial agents have<br />

been members <strong>of</strong> populations vulnerable to the authority <strong>of</strong><br />

medical science. In the 18th century, British scientist Edward<br />

Jenner infected himself with tiny traces <strong>of</strong> smallpox-rich pus<br />

to prove that the immune system could build up tolerance<br />

to illness, thereby establishing a precedent for the evolution<br />

<strong>of</strong> vaccines. But as Susan Lederer has described in her book<br />

Subjected to Science, in the 19th and 20th centuries, a large<br />

number <strong>of</strong> scientists eager to test new vaccines gravitated<br />

toward soldiers, prisoners, children, prostitutes, the elderly,<br />

and the mentally retarded, <strong>of</strong>ten with unimaginably brutal<br />

consequences. In 1908, for example, when pediatricians at<br />

the University <strong>of</strong> Pennsylvania wanted to perform diagnostic<br />

tests for tuberculosis, they intentionally infected more than<br />

140 children from a nearby Catholic orphanage, most <strong>of</strong><br />

whom were under eight years old. In 1911, Hideyo Noguchi,<br />

a microbiologist sponsored by the Rockefeller University,<br />

subjected over 400 patients to luetin, the causative agent <strong>of</strong><br />

syphilis. 1<br />

In the case <strong>of</strong> Botox injections, however, we see a transformation<br />

in the target audience <strong>of</strong> experimental infection<br />

from the most vulnerable to the most elite, while the parameters<br />

<strong>of</strong> what delineates “infection” have become utterly<br />

negotiable. At $300-500 a pop, vanity-obsessed dowagers<br />

and their cohorts are willing to pay exorbitant fees for the<br />

privilege <strong>of</strong> becoming vehicles for transporting dangerous

strains <strong>of</strong> bacteria in their foreheads—bacteria for which scientists<br />

have still not found a vaccine. Only under the genius<br />

<strong>of</strong> capitalism can a toxic killer grow up to become a cosmetic<br />

amenity.<br />

Initially, Botox injections seem to be the latest tool<br />

in an enormous arsenal <strong>of</strong> medical implants, injections, and<br />

other cosmetic technologies that include collagen, silicone,<br />

and even Gore-Tex. Virtually all <strong>of</strong> the organic or synthetic<br />

materials injected or implanted into human bodies produce<br />

physical side effects, many far worse than the petulant ennui<br />

that <strong>of</strong>ten leads one to pursue cosmetic procedures in the<br />

first place. As Elizabeth Haiken has described, in the first<br />

decades <strong>of</strong> the 20th century, doctors injected paraffin wax<br />

mixed with olive oil, goose grease, and vegetable soap into<br />

their patients’ faces, breasts, and legs in order to banish<br />

wrinkles and “sculpt” body parts to meet the cultural expectations<br />

<strong>of</strong> the era. 2 The practice ended by the 1930s with the<br />

high incidence <strong>of</strong> paraffin-related cancers, but the desire for<br />

a sculpted, malleable body among patients persisted.<br />

In the mid-1960s, famed San Francisco stripper Carol<br />

Doda injected a pint <strong>of</strong> silicone directly into each <strong>of</strong> her<br />

breasts. This was much more silicone than the standard<br />

amount used in breast implants produced by Dow Corning,<br />

which were taken <strong>of</strong>f the market three decades later amid<br />

a firestorm <strong>of</strong> controversy and litigation. <strong>And</strong> while the use<br />

<strong>of</strong> autologous human fat, which is cleaned <strong>of</strong> biological<br />

impurities before it is injected, seemed promising in the<br />

early 1990s, recent case studies have revealed its unsavory<br />

side effects. At best, the fat migrates from the injection<br />

site to one’s least-favored body part to join its kin; at worst,<br />

the fat forms an unsightly bas-relief comparable to the shape<br />

and volume <strong>of</strong> a small dwarf. The migration <strong>of</strong> autologous fat<br />

in penile enlargement procedures shocked many men who<br />

found themselves looking at penises with truly mushroomshaped<br />

heads.<br />

The use <strong>of</strong> Botox marks a departure from the history <strong>of</strong><br />

earlier cosmetic implants and injections in two distinct ways.<br />

First, it does not simply introduce an organic product (such<br />

as paraffin or collagen) into the body; it introduces a living<br />

microorganism, and a highly toxic one at that. Second, Botox<br />

injections do not seek merely to produce youthful-looking<br />

skin, or to aesthetically reshape a facial feature that will<br />

continue to function normally. The goal <strong>of</strong> the Botox injection<br />

is to paralyze and otherwise obliterate the function <strong>of</strong><br />

the collateral muscles in the forehead, just above the bridge<br />

<strong>of</strong> the nose. In practical terms, this means that one needs to<br />

be willing to sacrifice subjective expression for wrinkle-free<br />

features. On some level, the allure <strong>of</strong> Botox injections may<br />

be similar to that <strong>of</strong> exotic delicacies whose charm resides<br />

in their power to put consumers in danger: one thinks <strong>of</strong><br />

the pleasure/pain dialectic derived from the poisonous substances<br />

found in absinthe, psychedelic mushrooms, and the<br />

Japanese fish called fugu. Botox, however, is distinguished<br />

from these organic materials as an impure toxin to the body<br />

that produces—however temporarily—a youthful appearance<br />

and not an aesthetic experience or altered state <strong>of</strong><br />

consciousness.<br />

The widespread use <strong>of</strong> Botox ushers the first period<br />

in the modern era—certainly since the rise <strong>of</strong> visual technologies<br />

in the mid-19th century—where facial expressions<br />

will be disaggregated from the signified meanings to which<br />

they are typically moored. Over time, physicians expect that<br />

Botox customers will have to forfeit use <strong>of</strong> their forehead<br />

or eyebrows, two key vectors through which humans typically<br />

engage in nonverbal communication. As Norbert Elias<br />

described in his classic study The Civilizing Process, facial<br />

gestures are a central part <strong>of</strong> the modern lexicon <strong>of</strong> performative<br />

visual cues that, along with etiquette and refined<br />

behavior, are public markers <strong>of</strong> social class. 3 In the 1860s,<br />

Nadar captured the prototype <strong>of</strong> the exaggerated furrowed<br />

brow in his photographs <strong>of</strong> Parisian asylum<br />

15<br />

patients; in the 1970s, John Belushi elevated the mischievous<br />

single-raised eyebrow to an art form on Saturday Night<br />

Live. Indeed, what the frozen foreheads <strong>of</strong> Botox consumers<br />

call to mind, more than anything else, is the passivity and<br />

imperturbability <strong>of</strong> European aristocracy. One imagines an<br />

unflappable, furrow-less Queen Victoria waving from her<br />

horse-drawn carriage, or perhaps the sunken, emotionless<br />

visage <strong>of</strong> Catherine de Medici in languid repose, with<br />

a pomegranate in one hand and an open book in another.<br />

These were faces indifferent to the whims <strong>of</strong> fashion or<br />

popular opinion, born not only to rule but to resist physical<br />

weaknesses that might link them with their social inferiors.<br />

The iconic value <strong>of</strong> unruffled monarchs and aristocrats<br />

may have represented the solidity <strong>of</strong> power in pre-modern<br />

times, but in our current media-saturated <strong>culture</strong>, the desire<br />

to humanize celebrities and political figures demands an<br />

increased capacity to physically express a wider spectrum<br />

<strong>of</strong> emotions than ever before. The fertile territory between<br />

these two competing ideals <strong>of</strong> public expression is precisely<br />

what <strong>And</strong>y Warhol mined in his multiple silk-screened<br />

portraits <strong>of</strong> Jackie Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe in the early<br />

1960s. During the national mourning over Princess Diana’s<br />

death in 1997, the British public, seeking psychological<br />

satisfaction, called in desperation for the royal family to<br />

exhibit its collective grief through open displays <strong>of</strong> emotion.<br />

Instead, the House <strong>of</strong> Windsor’s decision to affect a traditional<br />

and icy aristocratic stance seemed to many to expose<br />

the artifice <strong>of</strong> hereditary power, rather than its permanence.<br />

In this sense, it is hard to conceive <strong>of</strong> a more O. Henryesque<br />

historical moment than our own: an era in which<br />

a volatile microorganism invisible to the naked eye has<br />

achieved popularity among a social niche that is completely<br />

indifferent to the political economy <strong>of</strong> global terrorism.<br />

Herein lies the paradox <strong>of</strong> Botox: how else to understand<br />

the staving-<strong>of</strong>f <strong>of</strong> aging, and ultimately the fear <strong>of</strong> death, by<br />

pursuing a medical treatment that promises to bring one in<br />

closer proximity to death than ever before?<br />

According to Science, US <strong>of</strong>ficials recently ranked C.<br />

botulinum second only to anthrax as the microorganism<br />

most likely to be used in bioterrorist activities—an unnerving<br />

statistic, considering that unlike anthrax, there is no<br />

known antidote even for common strains <strong>of</strong> the bacterium. 4<br />

Indeed, any country that can manufacture mass quantities<br />

<strong>of</strong> C. Botulinum—let alone synthesize new mutant strains<br />

<strong>of</strong> it—will have a weapon <strong>of</strong> incalculable power. After all,<br />

even the cosmetic use <strong>of</strong> Botox does not work to protect the<br />

immune system, but instead works to erode the body’s natural<br />

defenses. In our enthusiasm to promote the ephemera<br />

<strong>of</strong> youth over the grace <strong>of</strong> maturity, could we be producing,<br />

however inadvertently, a passive army <strong>of</strong> terrorists clad not<br />

in combat boots but in Prada heels?<br />

1 Susan Lederer, Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America Before<br />

the Second World War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), p. 60.<br />

2 Elizabeth Haiken, “Modern Miracles: The Development <strong>of</strong> Cosmetic Prosthetics,” in Kath-<br />

erine Ott et al, <strong>Art</strong>ificial Parts, Practical Lives: Modern Histories <strong>of</strong> Prosthetics<br />

(New York: NYU Press, 2002), pp. 171-198.<br />

3 See Norbert Elias, The Civilizing Process, [1937], trans. Edmund Jephcott (New York:<br />

Urizen Books, 1978).<br />

4 Donald Kennedy, “Beauty and the Beast,” Science vol. 295 (March 1, 2002), p. 1601.<br />

opposite: Franz Xaver Messerschmidt’s 18th-century character heads from an age before<br />

Botox. Clockwise: the contrarian; the smiling old man; the mischievous man; the beaked man.

leFtovers / how to use scotch tape<br />

Paul lukaS<br />

We’ve all heard the cliché about “the gift that keeps on<br />

giving.” Those words never rang truer for me than they did<br />

last Christmas, when a friend <strong>of</strong> mine gave me a small,<br />

stocking-stuffer-ish gift: an old metal Scotch tape dispenser<br />

from 1942, scavenged at a secondhand store, its tape roll<br />

still intact but now hopelessly gummed up. At first glance<br />

it appeared to be just another eye-pleasing tchotchke given<br />

from one design geek to another. Upon closer inspection,<br />

however, it has turned out to be a veritable treasure trove <strong>of</strong><br />

corporate and design history.<br />

All artifacts are historical documents, <strong>of</strong> course, but the<br />

Scotch tape dispenser <strong>of</strong>fers an unusually broad window on<br />

several historical fronts, in part because both the product<br />

and its manufacturer, 3M, remain staples <strong>of</strong> the consumer<br />

landscape today, making time-wrought changes easy to<br />

gauge. Let’s start with the product name itself, which is<br />

printed on the dispenser’s side: Scotch Cellulose Tape. This<br />

sounds vaguely <strong>of</strong>f, because most <strong>of</strong> us would think <strong>of</strong> it<br />

as cellophane tape, not cellulose. But cellophane is a cellulose<br />

derivative, and in 1942 it was a trademarked product<br />

<strong>of</strong> DuPont, which would not allow 3M to use it as part <strong>of</strong> the<br />

product’s name. That is also why the dispenser’s front panel<br />

features a little logo seal that reads: “Made <strong>of</strong> Cellophane<br />

[Trademark], The DuPont Cellulose Film.”<br />

Although Scotch is a ubiquitous brand today, its familiar<br />

plaid design motif is absent on the dispenser. In order to<br />

understand why, we need to go back to the origin <strong>of</strong> the<br />

brand name itself. “Scotch” was born in 1925, when a 3M<br />

engineer named Richard Drew created a form <strong>of</strong> masking<br />

tape that he envisioned being used by auto painters. But his<br />

two-inch-wide tape had adhesive only at the outer edges,<br />

not in the middle, much to the frustration <strong>of</strong> a local painter<br />

who tried one <strong>of</strong> Drew’s prototype rolls. As the tape kept<br />

falling <strong>of</strong>f the surfaces to which it had been applied, the<br />

exasperated painter told Drew, “Take this tape back to those<br />

Scotch bosses <strong>of</strong> yours and tell them to put more adhesive<br />

on it!” In this context, “Scotch” was an ethnic slur connoting<br />

stinginess—an unlikely source for a brand name, but one<br />

that served 3M well during the Depression, when Scotch<br />

tape became a symbol <strong>of</strong> thrift and do-it-yourself mending.<br />

This helps explain the brand’s rather austere blue-and-white<br />

design visage during its first two decades <strong>of</strong> existence. The<br />

more playful plaid motif appeared in 1945, as national optimism<br />

surged in the wake <strong>of</strong> WWII.<br />

On the other side <strong>of</strong> the dispenser, in block letters, is the<br />

manufacturer’s name: Minnesota Mining & Mfg. Co. Many<br />

<strong>of</strong> us have forgotten—indeed, if we ever knew—that these<br />

words are the source <strong>of</strong> 3M’s three ems. Indeed, 3M has<br />

become so synonymous with high-tech polymer innovation<br />

that a hardscrabble activity like mining seems hopelessly<br />

old-economy by comparison. But in fact the firm was founded<br />

in 1902 by a group <strong>of</strong> Minnesota investors who planned<br />

to mine a mineral deposit for grinding wheel abrasives.<br />

The abbreviation “3M”—not quite an acronym, more like a<br />

ligature—entered the corporate lexicon soon enough, but<br />

old-timers in the Twin Cities region still refer to the company<br />

as “Mining” (as in “Oh sure, I used to work for Mining”).<br />

Those looking for present-day manifestations <strong>of</strong> the company’s<br />

old name will be pleased to learn that 3M’s stock-ticker<br />

symbol is MMM, and that its Internet domain name is mmm.<br />

com.<br />

3M’s nomenclatorial transition from unwieldy 15syllable<br />

name to two-character symbol was already under<br />

way in the early 1940s, as is evident in the company’s old<br />

logo, which is printed on both sides <strong>of</strong> the tape dispenser.<br />

The spelled-out name and “3M Co.” both appear on<br />

17<br />

the logo, a busy jumble <strong>of</strong> typography and geometry. That<br />

logo design is a variation on one that first appeared in 1906;<br />

its basic diamond-within-a-circle template remained 3M’s<br />

visual signature until 1950, when the first <strong>of</strong> several revisions<br />

took place. Each subsequent logo facelift has moved<br />

toward simplicity, culminating—for now, at least—in the<br />

current 3M logotype, whose simple sans serif typography<br />

was designed by the New York firm Siegel & Gale in 1977.<br />

Tucked into the dispenser is a small instruction sheet.<br />

Imaginatively entitled “How and Where to Use Scotch<br />

Cellulose Tape,” it uses a series <strong>of</strong> captioned illustrations to<br />

explain the product’s function. Repeated mention is made <strong>of</strong><br />

the dispenser’s “sawtooth edge”: One caption instructs<br />

the consumer to “pick up tape between roll and sawtooth<br />

edge”; another helpfully tells the user to “pull desired length<br />

[<strong>of</strong> tape] and tear down against sawtooth edge.” While all<br />

this may seem superfluous today, it’s worth remembering<br />

that the first tape dispenser with a built-in cutter blade didn’t<br />

appear until 1932, and the design patent for this one (one <strong>of</strong><br />

many patents listed by number on the dispenser’s bottom<br />

panel and, like all American patents, accessible at the United<br />

States Patent and Trademark Office’s website, www.uspto.<br />

gov) wasn’t filed until 1939. So 3M’s decision to leave nothing<br />

to chance may well have been warranted.<br />

As it happens, the whole thing will soon come full circle,<br />

because the instruction sheet is all tattered and crinkled and<br />

looks like it’s about to fall apart. At which point I will reach<br />

across my desk, deploy a certain sawtooth edge, and patch<br />

the sheet back together with some fresh Scotch tape.<br />

colors / saFety orange<br />

Tim Griffin<br />

These are the days <strong>of</strong> disappearing winters, and <strong>of</strong> anthrax<br />

spores whose origin remains unknown, or unrevealed.<br />

Concrete phenomena float on abstract winds, seeming<br />

like mere signatures <strong>of</strong> dynamics that supercede immediate<br />

perception. The world is a living place <strong>of</strong> literature,<br />

interstitial, eclipsing objects with the sensibility <strong>of</strong> information,<br />

and experience floating on the surface <strong>of</strong> lexicons.<br />

Everything is so characterless and abstract as the weather:<br />

Wars are engaged without front lines, and weapons operate<br />

according to postindustrial logic, intended to destabilize<br />

economies or render large areas uninhabitable by the<br />

detonation <strong>of</strong> homemade “dirty bombs” that annihilate<br />

<strong>culture</strong> but do little damage to hard, architectural space.<br />

Radical thought is also displaced, as the military, not the<br />

academy, <strong>of</strong>fers the greatest collective <strong>of</strong> theorists today; all<br />

possibilities are considered by its think tanks, without skepticism<br />

or humanist pretensions, and all nations are potential<br />

targets. Ordinary health risks described in the popular press<br />

are totally relational, regularly enmeshing microwaves and<br />

genetic codes; the fate <strong>of</strong> ice caps belongs to carbon. Everything<br />

is a synthetic realism. Everything belongs to safety<br />

orange.<br />

It is a gaseous color: fluid, invisible, capable <strong>of</strong> moving<br />

out <strong>of</strong> those legislated topographies that have been<br />

traditionally fenced <strong>of</strong>f from nature to provide significant<br />

nuances for daily living. Perhaps it is a perfume: an optical<br />

Chanel No. 5 for the turn <strong>of</strong> the millennium, imbuing our<br />

bodies with its diffuse form. (Chanel was the first abstract<br />

perfume, as it was completely chemical and not based on<br />

any flower; appropriately, it arrived on the scene at roughly<br />

the same time as Cubism.) The blind aura <strong>of</strong> safety orange<br />

has entered everyday living space. One pure distillation<br />

appears in the logo for Home Depot, which posits one’s<br />

photos: Ricardo de Oliveira

most intimate sphere, the household, as a site that is under<br />

perpetual construction, re-organization, and improvement.<br />

The home becomes unnatural, industrial, singed with toxic<br />

energy. Micros<strong>of</strong>t also uses the color for its lettering,<br />

conjuring its associative power to suggest that a scientific<br />

future is always here around us, but may be fruitfully<br />

harnessed (Your home computer is a nuclear reactor).<br />

Such associative leaps are not unique. In postindustrial<br />

capitalism, experience is <strong>of</strong>ten codified in color. During the<br />

economic surge <strong>of</strong> the past decade, corporations recognized<br />

and implemented on a grand scale what newspapers<br />

documented only after the onset <strong>of</strong> the recession: that<br />

colors function like drugs. Tunneled through the optic<br />

nerve, they generate specific biochemical reactions and<br />

so determine moods in psychotropic fashion; they create<br />

emotional experiences that lend themselves to projections<br />

upon the world, transforming the act <strong>of</strong> living into lifestyle.<br />

Something so intangible as emotion, in turn, assumes a<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> property value as it becomes intimately maneuvered<br />

by, and then associated with, products. (One business<br />

manual recently went so far as to suggest that “consumers<br />

are our products.”)<br />

The iMac, to take one artifact <strong>of</strong> the 1990s, was<br />

introduced to the general public in a blue that was more<br />

than blue: Bondi Blue, which obtained the emotional heat<br />

accorded to the aquatic tones <strong>of</strong> a cosmopolitan beach<br />

in Australia, for which the color is named. Similarly, the<br />

iMac’s clear sheath is neither clear nor white—it is Ice.<br />

(Synesthesia reigns in capitalism; postindustrial exchange<br />

value depends on the creation <strong>of</strong> ephemeral worlds and<br />

auras within which to house products. <strong>And</strong> so, as colors<br />

perform psychotropic functions, total, if virtual, realities<br />

are located within single, monochromatic optical fields.<br />

Control <strong>of</strong> bodies, the original role designated for safety<br />

orange, is set aside for access to minds, which adopt the<br />

logic <strong>of</strong> addiction.) In fact, the 1990s boom might be usefully<br />

read through two specific television commercials that<br />

were geared to hues: It began with the iMac’s introduction<br />

in blue, orange, green and gray models, in a spot that<br />

was accompanied by the Rolling Stones lyric “She comes<br />

in colors.” Later, against the backdrop <strong>of</strong> 2001’s dot-com<br />

wasteland, Target released an advertisement featuring<br />

shoppers moving through a hyper-saturated, blood-red,<br />

vacuum-sealed field <strong>of</strong> repeating corporate logos—colors<br />

and brands were by then entirely deterritorialized, lifted<br />

from objects and displaced onto architecture—to the sound<br />

<strong>of</strong> Devo’s post-punk, tongue-in-cheek number “It’s a<br />

Beautiful World.”<br />

Devo <strong>of</strong>ten wore jumpsuits <strong>of</strong> safety orange, which<br />

was, at the time, the color <strong>of</strong> nuclear power plants and<br />

biohazards—a color created to oppose nature, something<br />

never to be confused with it. It is the color <strong>of</strong> information,<br />

bureaucracy, and toxicity. Variations <strong>of</strong> orange have <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

played this role. Ancient Chinese bookmakers, for example,<br />

printed the edges <strong>of</strong> paper with an orange mineral to save<br />

their books from silverfish.<br />

Times change. In 1981, the Day-Glo connoisseur Peter<br />

Halley suggested that New Wave bands like Devo were<br />

“rejecting the cloddish substance <strong>of</strong> traditional humanistic<br />

values,” comparing their work to that <strong>of</strong> the Minimalists.<br />

(All colors are minimal.) Yet the course <strong>of</strong> Devo has been<br />

the course <strong>of</strong> <strong>culture</strong>: the band’s rejection <strong>of</strong> humanistic<br />

values has become more abstract and expansive, and<br />

enmeshed in cultural t<strong>issue</strong>. Their music moved away from<br />

the specialized artistic realm <strong>of</strong> electro-synth composers<br />

like Robert Fripp and Brian Eno (who produced the band’s<br />

first music in a German studio at the behest <strong>of</strong> David<br />

Bowie) and into the world. First, it appeared for the mass<br />

audiences <strong>of</strong> the television show Pee-wee’s Playhouse,<br />

for whom the band wrote music. More recently, its band<br />

members have written music to accompany Universal<br />

Studio’s Jurassic Park ride and, most recently,<br />

19<br />

Purina Cat Chow commercials. Their anti-humanism no<br />

longer approaches <strong>culture</strong> from any critical remove; there is<br />

no synthetic outside from which to unveil the bureaucratic,<br />

unnatural structures <strong>of</strong> a social façade that presents itself<br />

as entirely natural. We have entered an era <strong>of</strong> synthetic<br />

realism.<br />

Devo is hardly alone in this kind <strong>of</strong> abstract migration.<br />

Vito Acconci has recounted a similar shift in his subjectivity,<br />

which may be traced in his shifting modes <strong>of</strong> production<br />

from poetry and sculpture to architecture and, finally,<br />

design—where his work is intended to disappear into the<br />

world. His changing taste in music is more to the point.<br />

He started in the 1960s by listening to the long, introspective<br />

passages <strong>of</strong> Van Morrison, then moved to the public<br />

speakers <strong>of</strong> punk in the 1970s. Today, he prefers Tricky,<br />

in whose music “it is impossible to tell where the human<br />

being ends and where the machine begins.” Individuals,<br />

in other words, have given way to engineers. Music by a<br />

composer like Moby has no signature sound or style; art by<br />

a painter like Gerhard Richter similarly leaps from genre to<br />

genre. Subjectivity itself is encoded for Napster. <strong>And</strong> safety<br />

orange, the color <strong>of</strong> this synthetic reality, becomes <strong>culture</strong>’s<br />

new heart <strong>of</strong> darkness.<br />

ingestion / how to cook a phoenix<br />

allen S. WeiSS<br />

Angels must be very good to eat. I would imagine they are very<br />

tender, between chicken and fish.<br />

— Peter Kubelka<br />

Every art form is a matrix <strong>of</strong> synaesthesia. Each art informs<br />

all others. Every sentence, every allusion, every word activates<br />

a different complex <strong>of</strong> sensations. These evidences<br />

should not be lost on our daily pleasures. As a translator,<br />

one is perpetually caught in the dilemmas that stem from<br />

these complexities. For example, one quandary I encountered<br />

was in Valère Novarina’s Le discours aux animaux,<br />

which ends with the sentence, “One day I played the horn<br />

like this all alone in a splendid woods, and the birds were<br />

becalmed at my feet when I named them one by one with<br />

their names two by two,” followed by a list <strong>of</strong> 1,111 imaginary<br />

birds, beginning with:<br />

la limnote, la fuge, l’hypille, le ventisque, le lure, le figile,<br />

le lépandre, la galoupe, l’ancret, le furiste, le narcile,<br />

l’aulique, la gymnestre, la louse, le drangle, le ginel, le<br />

sémelique, le lipode, l’hippiandre, le plaisant, la cadmée, la<br />

fuyau, la gruge, l’étran, le plaquin, le dramet, le vocifère, le<br />

lèpse, l’useau, la grenette, le galéate… 1<br />

Needless to say, it would be impossible to translate such<br />

names, and transliteration would hardly be satisfying, as<br />

it would be but sheer linguistic play. Rather, the challenge<br />

is to recreate the very conditions <strong>of</strong> such idiosyncratic<br />

naming, to imitate not Novarina’s words, but his poetic<br />

methods; to designate as language itself designates; to<br />

be a demiurge unto one’s own speech. In the ornithological<br />

context, most names are in some part descriptive, referring<br />

either to a bird’s relation to its habitat, to its physical<br />

aspect, behavioral conditions, or decidedly unverifiable<br />

mythical analogies. I would, in all modesty, propose<br />

the following English parallels (if not, strictly speaking,<br />

translations):<br />

pimwhite, sandkill, partch, barnscrub, stiltback, goskit,<br />

persill, peeve, phyllist, corntail, perforant, titibit, queedle,<br />

jewet, phew, marshquiver, graywhip, corvee, rillard, preem,<br />

peterwil, cassenut, flusher, willowgyre, trillet, silverwisp,<br />

eidereye, wheeltail, ptyt, jeebill, wheatspit...

In an early volume, Flamme et festin, I had begun to muse<br />

upon the possibility <strong>of</strong> creating recipes for just such<br />

creatures, but I now must admit that this was a rather<br />

disingenuous proposition. Not because these birds are<br />

imaginary, but simply because each such name is a hapax<br />

(a word that occurs only once in a language), appearing<br />

without predication or description, in a context that <strong>of</strong>fers<br />

no denotations, but only the undemonstrable connotations<br />

implied by the name itself. (For how can we ever really determine<br />

if the cassenut actually breaks open nut shells in its<br />

quest for nourishment, or if the barnscrub lives in barns like<br />

certain swallows and owls, or if the sandkill is a shore bird?)<br />

Any such hapax is a pure signifier without signified, a word<br />

without object—we can never know whether or not it is a<br />

figment <strong>of</strong> the imagination. While they might enter a dictionary<br />

<strong>of</strong> imaginary creatures, they cannot be catalogued in a<br />

universal encyclopedia, for sheer lack <strong>of</strong> information.<br />

Years ago, I had hoped for some practical help from<br />

the International Society <strong>of</strong> Cryptozoology, located in<br />

Tucson, Arizona. But none was forthcoming. Cryptozoology<br />

is the science <strong>of</strong> nonexistent animals, such as the<br />

banshee, centaur, chimera, griffon, kraken, minotaur, rukh,<br />

unicorn—not to mention all those nameless species that<br />

haunt our fantasies and nightmares. I sought more precise<br />

qualifications in order to fortify my belief that this obscure<br />

field <strong>of</strong> wisdom could be made more joyous through its<br />

intersection with cryptogastronomy. However, it was rather<br />

in the abstract realm <strong>of</strong> theory that I found my inspiration,<br />

specifically in Umberto Eco’s article “Small Worlds,” 2 where<br />

he proposes a theory <strong>of</strong> fictional discourse whereby one may<br />

judge truth value and descriptive validity within imaginary<br />

or possible worlds. Such domains span the spectrum from<br />

those most resembling our quotidian environment to the<br />

farthest reaches <strong>of</strong> the speculative utopian imagination; their<br />

epistemological status may be verisimilar, non-verisimilar,<br />

inconceivable, or even impossible. In all cases, such worlds<br />

can be either relatively empty or furnished, depending upon<br />

the amount <strong>of</strong> information given about a particular fictional<br />

milieu. Following this lead, it is obvious that the general<br />

world <strong>of</strong> Novarina’s animals is relatively unfurnished, and<br />

the specific context in which the birds appear is absolutely<br />

impoverished: we are <strong>of</strong>fered no ornithological information<br />

whatsoever, and thus cannot begin to conceive <strong>of</strong> appropriate<br />

recipes for them.<br />

But, luckily, this is not always the case for fanciful<br />

animals. Consider the phoenix, that mythical bird which is<br />

consumed in spontaneously generated flames, to be reborn<br />

from its own ashes, a symbol particularly appreciated by<br />

the early Christian church for its blatantly resurrectional<br />

qualities. Indeed, we know much more about the phoenix<br />

than we do <strong>of</strong> many real animals. The history <strong>of</strong> this bird is<br />

ancient, and it appears in Hesiod, Herodotus, Plutarch,<br />

Tertulius, Tacitus, Pliny, Martial, Ovid, Dante, Cyrillus, Saint<br />

Ambrose, and Milton, among many others. It is estimated<br />

that half <strong>of</strong> the pre-modernist European poets have written<br />

about it, with, for example, seven mentions in Shakespeare.<br />

There thus exists a wealth <strong>of</strong> detail, albeit somewhat contradictory<br />

at times, about this creature. The 1967 edition <strong>of</strong><br />

the Encyclopedia Britannica informs us that the phoenix,<br />

whose ecosphere is the Arabian peninsula, is as large as an<br />

eagle, with scarlet and gold plumage, and a melodious cry. It<br />

is most <strong>of</strong>ten said to resemble the purple heron (Ardea purpurea),<br />

and less <strong>of</strong>ten the stork, egret, flamingo, or even the<br />

Bird <strong>of</strong> Paradise. Part <strong>of</strong> the confusion seems to stem from<br />

the fact that in ancient Egyptian mythology, the hieroglyph<br />

<strong>of</strong> the benu—a solar symbol, as is the pheonix— resembles<br />

a heron or some other large water-fowl, and a purple heron<br />

was sacrificed by the priests <strong>of</strong> Heliopolis (City <strong>of</strong> the Sun)<br />

in a grand ceremony every 500 years. It would seem that the<br />

sacred powers invested in this hieroglyph greatly influenced<br />

the perception <strong>of</strong> the natural world, as well as consequent<br />

ornithological classification. The life-cycle <strong>of</strong><br />

20<br />

the phoenix is unique in the animal world, here described in<br />

the classic account by Ovid in the Metamorphoses:<br />

There is one living thing, a bird, which reproduces and<br />

regenerates itself, without any outside aid. The Assyrians<br />

call it the phoenix. It lives, not on corn or grasses, but on the<br />

gum <strong>of</strong> incense, and the sap <strong>of</strong> balsam. When it has completed<br />

five centuries <strong>of</strong> life, it straightway builds a nest for itself,<br />

working with unsullied beak and claw, in the topmost branches<br />

<strong>of</strong> some swaying palm. Then, when it has laid a foundation<br />

<strong>of</strong> cassia, and smooth spikes <strong>of</strong> nard, chips <strong>of</strong> cinnamon bark<br />

and yellow myrrh, it places itself on top, and ends its life amid<br />

the perfumes. Then, they say, a little phoenix is born anew<br />

from the father’s body, fated to live a like number <strong>of</strong> years. 3<br />

The decadent Roman Emperor Heliogabalus—who<br />

shared with the phoenix a part <strong>of</strong> solar divinity—was a great<br />

gourmet and glutton, especially fond <strong>of</strong> such delicacies as<br />

flamingo heads, peacock tongues, and cockscombs cut from<br />

the live animal. He once sent hunters to the land <strong>of</strong> Lydia,<br />

<strong>of</strong>fering two hundred pieces <strong>of</strong> gold to the man who would<br />

bring back a phoenix. None did. An explanation for this prodigious<br />

culinary desire can be extrapolated from Jean-Pierre<br />

Vernant’s analysis:<br />

The incandescent life <strong>of</strong> the phoenix follows a circular<br />

course, increasing and decreasing, with birth, death and<br />

rebirth following a cycle that passes from an aromatic bird<br />

closer to the sun than the eagle flying at great heights, to the<br />

state <strong>of</strong> a worm in rotting matter, more chthonian than the<br />

snake or the bat. From the bird’s ashes, consumed at the end<br />

<strong>of</strong> its long existence in a blazing aromatic nest, is born a<br />

small earth-worm, nourished by humidity, which shall in turn<br />

become a phoenix. 4<br />

What more appropriate dish for a solar emperor?<br />

Perhaps tired <strong>of</strong> the repeated human sacrifices to his own<br />

divine nature, he sought a rarer <strong>of</strong>fering. For Heliogabalus,<br />

true to his own solar name, wished to bring heaven down<br />

to earth in a cruel and erotic scenario <strong>of</strong> death, so that the<br />

blood <strong>of</strong> the human sacrifices organized by the Priest <strong>of</strong><br />

the Cult <strong>of</strong> the Sun, flowing from the sacrificial altars <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Temple <strong>of</strong> Emesa, might have well been augmented by some<br />

more decidedly supernatural <strong>of</strong>ferings. The lifecycle <strong>of</strong> the<br />

phoenix is the very allegory <strong>of</strong> cuisine, taken in its structural<br />

instance, as it spans the antithetical conditions <strong>of</strong> raw/<br />

cooked, cold/hot, fresh/rotten, dry/moist, aromatized/gamy.<br />

The phoenix would thus be the perfect dish and the ideal<br />

<strong>of</strong>fering, paradoxically encompassing the contradictory possibilities<br />

<strong>of</strong> diverse cooking techniques, inherent alimentary<br />

differences, and sacred symbolism. Like the transubstantiation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the host, or cannibalistic communion, the eating <strong>of</strong><br />

the phoenix would constitute a truly transcendental gastronomic<br />

act.<br />

Setting aside whatever extravagance Heliogabalus<br />

might have had in mind, let us consider appropriate recipes<br />

for a phoenix. The end <strong>of</strong> the phoenix’s lifecycle, when it is<br />

consumed in its own flames, quite obviously suggests the<br />

proper manner <strong>of</strong> cooking: the phoenix is to be roasted<br />

outdoors over a fire <strong>of</strong> sweet-smelling resinous woods and<br />

aromatic herbs. This suggestion corresponds to the symbolic<br />

exigencies <strong>of</strong> this sacred bird, a symbolism elucidated<br />

in Claude Lévi-Strauss’s analysis <strong>of</strong> culinary practice in The<br />

Origin <strong>of</strong> Table Manners. The difference between the roast<br />

and the boiled entails respectively the following oppositions,<br />

all pointing to the fact that “one can place the roast<br />

on the side <strong>of</strong> nature and the boiled on the side <strong>of</strong> <strong>culture</strong>”:<br />

non-mediated (cooked directly on an open flame) versus<br />

mediated (cooked in water in a closed utensil); masculine<br />

(open fire) versus feminine (protected hearth); exo-cuisine<br />

(cooked outside and destined for foreigners) versus endocuisine<br />

(cooked in a recipient and destined for the family

or a closed group). 5 Thus while the roast is the sort <strong>of</strong> dish<br />

<strong>of</strong>fered to strangers, the boiled is destined for a small, intimate,<br />

closed group. Furthermore, the sociological markers<br />

are even more precise, ins<strong>of</strong>ar as boiling fully conserves the<br />

meat and its juices, while roasting entails destruction or<br />

loss. The former is popular and economical, the latter aristocratic<br />

and prodigious, with the smoke rising as an <strong>of</strong>fering<br />

to the gods. The boiled is an empirical culinary mode, while<br />

the roast is a transcendental one. The phoenix is, therefore,<br />

the most festive <strong>of</strong> dishes, truly appropriate for a once-in-alifetime<br />

occasion.<br />

The preparation <strong>of</strong> the phoenix is relatively simple, and<br />

similar to the preparation <strong>of</strong> much large game. First <strong>of</strong> all,<br />

as is suggested by its habits, the phoenix should be hung,<br />

so that the flavor <strong>of</strong> the flesh becomes gamy, according to<br />

taste, somewhere between the bird state and the worm state.<br />

Afterwards, it should be marinated in a mixture <strong>of</strong> red wine,<br />

herbs and spices (see infra). The reason for the marinade<br />

is, however, the opposite <strong>of</strong> what is usually the case. Many<br />

types <strong>of</strong> large game need be hung and marinated in order to<br />

s<strong>of</strong>ten their flesh, as their free-ranging lives produces a far<br />

greater proportion <strong>of</strong> muscle to fat than is found in domestic<br />

fowl and livestock. For the phoenix, however, tenderizing<br />

is unnecessary, since it is a very long-lived and sedentary<br />

creature, and thus has an extremely high and volatile fat<br />

content. (This complicates both hanging and roasting, as its<br />

flesh easily falls to pieces if tenderized too long.) As it has a<br />

distinct tendency to burst into flame, a marinade is necessary<br />

for moistening and flame-retarding purposes, and it is<br />

precisely for that reason that the bird should be continually<br />

basted with the marinade mixed with a bit <strong>of</strong> clarified butter<br />

or neutral vegetable oil. As for the recipes themselves,<br />

we should beware <strong>of</strong> misleading analogies. Certain <strong>of</strong> them<br />

believe that the phoenix should be treated like the heron.<br />

The Oxford Companion to Food reveals that the gray heron<br />

(Ardea cinerea) was treated throughout the European Middle<br />

Ages like other “great birds” such as the stork, crane, and<br />

peacock: stuffed with garlic and onions and then roasted<br />

whole, with an <strong>of</strong>ten lavish presentation, including gilding<br />

and the decorative replacement <strong>of</strong> its feathers. 6 But it<br />

is obvious that, though roasting is indeed the proper technique,<br />

the mere accompaniment <strong>of</strong> onions and garlic is an<br />

impoverishment <strong>of</strong> the phoenix’s culinary possibilities. Like<br />

all game, the flesh is already strongly flavored by what it<br />

feeds on: in this case, gum <strong>of</strong> incense, sap <strong>of</strong> balsam, and<br />

diverse savory herbs and berries (the phoenix is a vegetarian<br />

bird, which adds to its symbolic allure <strong>of</strong> purity); and the<br />

composition <strong>of</strong> its nest suggests that certain combinations<br />

<strong>of</strong> aromatic herbs and spices found in the Middle East should<br />

be used in the stuffing, such as the already mentioned cinnamon,<br />

cassia, frankincense, myrrh, and nard, to which we<br />

can add cardamom, ginger, turmeric, cumin, nutmeg, mace,<br />

sumac, allspice, etc. In short, many <strong>of</strong> the riches <strong>of</strong> the spice<br />

trade are appropriate; they judiciously harmonize with the<br />

phoenix’s flesh. The particular mixtures <strong>of</strong> spices, like Indian<br />

curries, differ from country to country and family to family.<br />

There is no “classic” recipe.<br />

There is little information about appropriate side<br />

dishes, though here too a false analogy reigns. In Greek,<br />

phoenix also means palm tree, and in Egyptian, the hieroglyph<br />

<strong>of</strong> the benu symbolizes the phoenix and, alternately,<br />

the palm tree; since both the tree and the bird are attributes<br />

<strong>of</strong> the sun god, they are <strong>of</strong>ten confused. This has led some<br />

to believe that the fruit <strong>of</strong> the date palm is either an appropriate<br />

stuffing or accompaniment. While such a rich fruit might<br />

well serve the purpose, I would much prefer a truffe sous<br />

cendres [truffle cooked in ashes] and some pomegranate<br />

jelly.<br />

It should be noted that the phoenix is so rare that<br />

its snob appeal by far supercedes that <strong>of</strong> all other<br />

luxury foods. Even the gold shavings and small gems<br />

21<br />

that Heliogabalus consumed mixed into his vegetables, or<br />

the huge pearls that Cleopatra dissolved in her beverages,<br />

are banal in comparison. The reason for this rarity is both<br />

because only one phoenix is said to exist at any given time,<br />

and because it is so very difficult to capture, as indicated<br />

by its life span: in the lowest estimate, Ovid places it at 500<br />

years; Tacitus claims that it corresponds to the Egyptian<br />

Sothic Cycle <strong>of</strong> 1,461 years; Pliny puts it at the length <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Platonic Year, the 12,994-year period needed for the sun,<br />

moon, and five planets to all return to their original heavenly<br />

positions; one extreme estimate suggests that its life span is<br />

97,000 years, but this seems ridiculous. Taking into account<br />

the ancient Egyptian ritual cycle would most probably lead<br />

one to accept the lowest estimate <strong>of</strong> 500 years. Despite its<br />

rarity, the phoenix is a foodstuff eminently worthy <strong>of</strong> consideration,<br />

and its absence from the culinary literature is most<br />

curious. It is hoped that this brief essay will to some extent<br />

aid in filling this noteworthy gastronomic gap.<br />

The International Society <strong>of</strong> Cryptozoology can be reached at P. O. Box 43070, Tucson,<br />

Arizona (AZ) 85733, USA. Telephone & fax: +1 520 884 8369.<br />

1 Valère Novarina, Le discours aux animaux (Paris, P.O.L., 1987), p. 321.<br />

2 Umberto Eco, The Limits <strong>of</strong> Interpretation (Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1994),<br />

pp. 64-82.<br />

3 Ovid, Metamorphoses, trans. Mary M. Innes (New York, Penguin, 1984), p. 345.<br />

4 Jean-Pierre Vernant, “Introduction” to Marcel Detienne, Les jardins d’Adonis (Paris,<br />

Gallimard, 1972), p. xxxiii.<br />

5 Claude Lévi-Strauss, L’Origine de manières de table (Paris, Plon, 1968), pp. 397-403.<br />

6 Alan Davidson, The Oxford Companion to Food (Oxford, Oxford University Press), p. 379.

maIN

ErNst HaEckEl aNd tHE mIcrobIal<br />

baroquE<br />

DaviD BroDy<br />

In 1895, a group <strong>of</strong> mountains along the spine <strong>of</strong> the Sierras<br />

in California was named to immortalize the apostles <strong>of</strong> evolution,<br />

pioneers <strong>of</strong> a new enlightenment. Mts. Darwin, Agassiz,<br />

and Mendel topped the elevational pecking order. Next in altitude,<br />

at 13,418 feet – higher than Mts. Wallace, Lamarck, and<br />

Huxley – came a peak named for the German zoologist Ernst<br />

Haeckel, who at the time <strong>of</strong> christening was in the full vigor <strong>of</strong><br />

his remarkable career.<br />

You may not have heard <strong>of</strong> Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919), but<br />

for 50 years or so, until his death, he was the most influential<br />

evolutionary theorist on the map. He did more to spread the gospel<br />

<strong>of</strong> evolution than all his fellow snow-capped honorees combined,<br />

lecturing, demonstrating, thundering, and publishing<br />

dozens <strong>of</strong> books, some technical, some popular. In the decades<br />

before World War I, prominent display <strong>of</strong> Haeckel’s books was<br />

de rigeur in European or American households seeking to seem<br />

educated, up-to-date, and non-dogmatic; his opinions – spiritual,<br />

aesthetic, philosophical, political – carried the imprimatur<br />

<strong>of</strong> unquestioned scientific objectivity. But Haeckel was more<br />

than a progenitor <strong>of</strong> the Carl Sagan-like scientist-celebrity. His<br />

immense ambition was founded upon a visionary’s graphic talent,<br />

manifested in biological illustrations so hallucinatory that<br />

his lithographs <strong>of</strong> microorganisms still threaten to overwhelm<br />

all sorts <strong>of</strong> categorical distinctions between art, nature, and<br />

science. These images, however, cannot be examined without<br />

acknowledging the omnivorous, Faustian hunger for consolidation<br />

<strong>of</strong> knowledge that produced them.<br />

Haeckel had made his name, in the 1860s, by describing<br />

hundreds <strong>of</strong> new species <strong>of</strong> radiolarians, publishing volume<br />

after volume <strong>of</strong> taxonomic description <strong>of</strong> this order <strong>of</strong> marine<br />

protozoan. What really set his work apart, though, was not<br />

the science but the plates. Whether this emphasis was<br />

entirely legitimate was debated at the time – had Haeckel<br />

over-embellished and idealized his observations or, as he<br />

claimed, had he discerned for the first time their underlying<br />

crystalline structure? Certainly no biologist before him had<br />

applied the study <strong>of</strong> solid geometry to precise descriptions <strong>of</strong><br />

organic phenomena, and the penetrating insights resulting<br />

from this détente <strong>of</strong> disciplines seemed to justify the boldness<br />

<strong>of</strong> Haeckel’s drawings. If the images were not optically true,<br />

then perhaps they were truer than true. Wasn’t a search for the<br />

pattern beneath the noise the higher purpose <strong>of</strong> science?<br />

If certain <strong>of</strong> Haeckel’s colleagues were dubious, the public<br />

was not. Weltratsel (The Riddle <strong>of</strong> the Universe), first <strong>issue</strong>d<br />

in 1895, sold more than half a million copies in Germany alone,<br />

an unheard-<strong>of</strong> number for the time, and was translated into<br />

thirty languages. Kunstformen der Natur, or <strong>Art</strong> Forms in<br />

Nature published in installments between 1899 and 1904, has<br />

arguably enjoyed an even broader audience. Its lavish images<br />

<strong>of</strong> self-enlacing, baroque jellyfish, with their translucent baldachins<br />

<strong>of</strong> tendrils, and his constellations <strong>of</strong> plankton magnified to<br />

Romanesque filigrees, 1 directly influenced the more self-consciously<br />

decorative, asymmetrical vocabulary <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong> Nouveau<br />

and Jugendstil – René Binet’s cast iron entrance gate to<br />

23<br />

the 1900 Paris Exposition, for example, was modeled on<br />

Haeckel’s beloved radiolarians. 2 <strong>Art</strong> Forms was eagerly perused<br />

by the Surrealists, notably Max Ernst, and almost certainly<br />

by the Bauhaus painters Klee and Kandinsky. Thus, even contemporary<br />

artists who have never seen the book can hardly have<br />

avoided the pulsations <strong>of</strong> its influence. 3 But, about this, more<br />

later.<br />

From his pr<strong>of</strong>essorship in Jena, the university town that was<br />

associated with the immortal polymaths Goethe, Schiller, and<br />

Hegel, Haeckel advocated Darwinism to a hostile world, declaring<br />

war on the medieval mystifications <strong>of</strong> religion and unleashing<br />

a barrage <strong>of</strong> invective at the Catholic Church. In contrast<br />

to Darwin and most <strong>of</strong> his fellow evolutionists, though, he did<br />

not confine himself to the role <strong>of</strong> sober secular materialist. His<br />

almost mystical obsession with a rational and progressive<br />

march toward biological perfection was far removed from the<br />

random impersonality <strong>of</strong> natural selection, and his contempt<br />

for religion did not stop him from establishing one <strong>of</strong> his own.<br />