The Wreck of DKM Bismarck − A Marine Forensics Analysis 1 The ...

The Wreck of DKM Bismarck − A Marine Forensics Analysis 1 The ...

The Wreck of DKM Bismarck − A Marine Forensics Analysis 1 The ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong><br />

A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

by<br />

James Cameron<br />

Robert O. Dulin, Jr.<br />

William H. Garzke, Jr.<br />

William Jurens<br />

Kenneth M. Smith, Jr.<br />

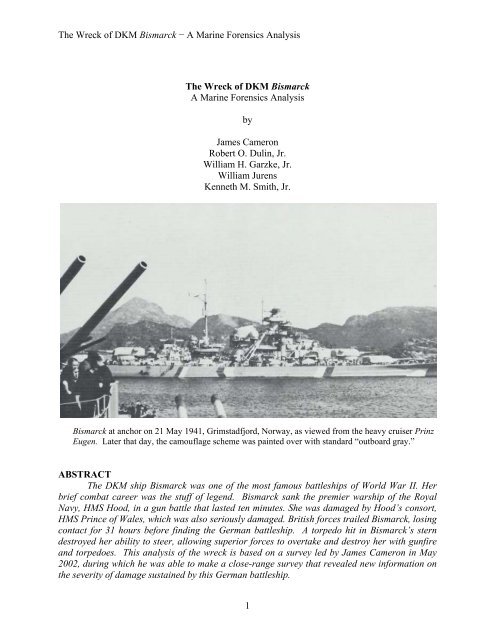

<strong>Bismarck</strong> at anchor on 21 May 1941, Grimstadfjord, Norway, as viewed from the heavy cruiser Prinz<br />

Eugen. Later that day, the camouflage scheme was painted over with standard “outboard gray.”<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> ship <strong>Bismarck</strong> was one <strong>of</strong> the most famous battleships <strong>of</strong> World War II. Her<br />

brief combat career was the stuff <strong>of</strong> legend. <strong>Bismarck</strong> sank the premier warship <strong>of</strong> the Royal<br />

Navy, HMS Hood, in a gun battle that lasted ten minutes. She was damaged by Hood’s consort,<br />

HMS Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales, which was also seriously damaged. British forces trailed <strong>Bismarck</strong>, losing<br />

contact for 31 hours before finding the German battleship. A torpedo hit in <strong>Bismarck</strong>’s stern<br />

destroyed her ability to steer, allowing superior forces to overtake and destroy her with gunfire<br />

and torpedoes. This analysis <strong>of</strong> the wreck is based on a survey led by James Cameron in May<br />

2002, during which he was able to make a close-range survey that revealed new information on<br />

the severity <strong>of</strong> damage sustained by this German battleship.<br />

1

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

This report is the distillation <strong>of</strong> decades <strong>of</strong> research into the design, characteristics, and<br />

operation <strong>of</strong> Germany’s most famous battleship, augmented by interviews and correspondence<br />

with <strong>Bismarck</strong> survivors and the dramatic results <strong>of</strong> a survey <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Bismarck</strong> wreck completed<br />

by James Cameron in May 2002. This has permitted the authors to accomplish this thorough<br />

marine forensics analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong>.<br />

<strong>Bismarck</strong> was the first battleship delivered to the German Navy in over 24 years.<br />

Restrained by the Versailles Treaty from building such ships, the Anglo-German Naval Treaty <strong>of</strong><br />

June 1935 allowed the Germans to build to battleships with a standard displacement <strong>of</strong> 35,000<br />

tons 1 . <strong>The</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> and Tirpitz were much larger than this limiting displacement because the<br />

German Navy was unwilling to use triple or quadruple turrets for their main armament 2 .<br />

Although <strong>Bismarck</strong> and Tirpitz have a similar arrangement to the Baden/Bayern design <strong>of</strong> World<br />

War I, the details <strong>of</strong> their armor, armament, and propulsion plants were very different. <strong>The</strong> actual<br />

displacement <strong>of</strong> these ships was kept secret.<br />

<strong>The</strong> keel for “Battleship F” was laid on 1 July 1936 at the Blohm and Voss Shipyard in<br />

Hamburg. <strong>The</strong> battleship was launched on 14 February 1939. <strong>Bismarck</strong> was commissioned on<br />

24 August 1940. Table 1 highlights the characteristics <strong>of</strong> this powerful, well-protected ship.<br />

Table 1<br />

Characteristics <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong><br />

Full Load Displacement 49,406 tonnes<br />

Maximum Displacement 50,405 tonnes<br />

Waterline Length 241.55 meters<br />

Waterline Beam 36.00 meters<br />

Draft (design) 9.30 meters<br />

Armament Eight 380mm in Twin Turrets<br />

Twelve 150mm in Twin Turrets<br />

Sixteen 105mm in Twin Mounts<br />

Sixteen 37mm Semi-Automatic Guns in Twin Mounts<br />

Twelve 20mm Single Machine Guns<br />

Four Arado-196 Floatplanes<br />

Shaft Horsepower 138,000 mhp<br />

Speed 30.12 Knots<br />

Endurance 9,500 miles at 19 Knots<br />

Fuel 8,294 tonnes<br />

Protection 320mm – Main Side Belt<br />

95mm – Deck (Magazines)<br />

80mm – Deck (Machinery)<br />

1 <strong>The</strong> Washington Naval Treaty, signed in 1922, defined standard displacement as “… the displacement<br />

<strong>of</strong> the vessel complete, fully manned, equipped, and ready for sea, including ammunition, provisions,<br />

fresh water for her crew, and miscellaneous stores and implements <strong>of</strong> every description to be carried in<br />

war, but not including fuel or reserve feed water.” Standard displacement was measured in long tons,<br />

2,240 pounds. Metric tons (tonnes) are defined as 1,000 kilograms (2,204 pounds).<br />

2 By the mid-1930s, naval design staffs struggled with the displacement limitations imposed by a series<br />

<strong>of</strong> naval disarmament treaties. For all practical purposes, all treaty displacement limitations expired on 31<br />

December 1936. Most battleships that were completed during the World War II era exceeded Treaty<br />

constraints.<br />

2

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

FLAWS IN THE DESIGN OF BISMARCK<br />

<strong>The</strong> dramatic story <strong>of</strong> the pursuit and destruction <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Bismarck</strong> was markedly<br />

influenced by deficiencies in her machinery arrangement, her radar equipment, and her<br />

antiaircraft armament:<br />

MACHINERY ARRANGEMENT<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong>, as was typical for German capital ships <strong>of</strong> both the World War I and<br />

World War II eras, featured a three-shaft main propulsion arrangement. Twin rudders, coupled<br />

together, were positioned aft <strong>of</strong> the three propellers. <strong>The</strong> leading edges <strong>of</strong> these rudders were<br />

less than two meters aft <strong>of</strong> the centerline propeller. <strong>The</strong> proximity the rudders to the centerline<br />

propeller was to be a major factor in the destruction <strong>of</strong> the German battleship.<br />

During engineering trials in the Baltic, as recalled by Baron von Mullenheim-Rechberg:<br />

“It was found with both rudders locked in an amidships position, the <strong>Bismarck</strong> could be held on<br />

course only with great difficulty. <strong>The</strong> reason for this was that the convergent design <strong>of</strong> her<br />

propeller shafts provided only a weak turning movement, even with the outboard shafts rotating<br />

in opposition at full power. 3 ” <strong>The</strong>se problems, encountered in calm water with the rudders<br />

locked amidships, revealed the near-impossibility <strong>of</strong> using her engines to steer a damaged<br />

<strong>Bismarck</strong> with no operational rudders, especially in heavy weather.<br />

RADAR EQUIPMENT<br />

During 1940, the German Navy began introducing new shipboard radar equipment on<br />

their warships. <strong>The</strong> radar aboard <strong>Bismarck</strong> was fitted after the trials <strong>of</strong> the 380-mm guns had<br />

been completed based on information gleaned from Baron von Müllenheim Rechberg 4 . <strong>The</strong><br />

Baron was puzzled by the decision to outfit the ship with radar equipment following the gunnery<br />

trials. When Norfolk was engaged on 23 May in the Denmark Strait, the firing <strong>of</strong> the two<br />

forward turrets disabled the two forward radars, making it necessary for Prinz Eugen to take the<br />

lead to search sector ahead <strong>of</strong> the formation with her radar. This exchange in ships would cause<br />

great confusion on board Hood in identifying <strong>Bismarck</strong> on 24 May. (<strong>The</strong> German heavy cruisers<br />

were very similar in appearance to the <strong>Bismarck</strong> and Tirpitz.)<br />

ANTIAIRCRAFT ARMAMENT<br />

<strong>Bismarck</strong> featured a mixed-caliber secondary armament, with six twin turrets mounting<br />

150mm guns intended to engage enemy surface ships combined with eight twin mounts fitted<br />

with 105mm guns for antiaircraft fire. This design feature, typical <strong>of</strong> German, Italian, and<br />

Japanese capital ships, was inferior to the concept adopted by the United States and British Royal<br />

navies <strong>of</strong> mounting a single battery <strong>of</strong> dual-purpose guns, adequate for both surface engagements<br />

and for antiaircraft fire. (<strong>The</strong> American dual-purpose gun was 127mm; the Royal Navy adopted<br />

a 134-mm gun for this service.)<br />

3<br />

Baron Burkard von Müllenheim-Rechberg. Battleship <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A Survivor’s Story. Annapolis,<br />

Naval Institute Press, 1980. Page 39.<br />

4<br />

Baron Burkard von Müllenheim-Rechbereg, as recalled during a conversation with authors Bill Garzke<br />

and Bob Dulin in Annapoolis, MD, 20 September 1980.<br />

3

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> 105mm battery on <strong>Bismarck</strong> was flawed in several other aspects. Due to the<br />

diversion <strong>of</strong> four new mounts to be used in a trade arrangement with the Soviet Union, four <strong>of</strong><br />

the older Dopp LC/31 type being used forward instead <strong>of</strong> the more modern Dopp LC/37 type,<br />

which were mounted aft. <strong>The</strong> 105mm mounts, interestingly, were unable to fully depress to<br />

engage very low-flying targets, such as enemy biplane torpedo bombers.<br />

<strong>The</strong> 37mm guns mounted on <strong>Bismarck</strong> were single-shot, semi-automatic weapons,<br />

capable <strong>of</strong> a maximum rate <strong>of</strong> fire <strong>of</strong> about 30 rounds per minute per gun. <strong>The</strong> comparable<br />

40mm B<strong>of</strong>ors machine guns mounted on modern American warships were capable <strong>of</strong> firing<br />

about 160 rounds per minute per gun.<br />

<strong>The</strong> antiaircraft armament on <strong>Bismarck</strong> was fatally flawed, as events were to show on the<br />

evening <strong>of</strong> the 26 th <strong>of</strong> May.<br />

PRINCE OF WALES AND HOOD ENGAGE BISMARCK<br />

<strong>Bismarck</strong> left Gydnia (Gotenhafen) at 0200 on 19 May 1941 and was joined by the heavy<br />

cruiser Prinz Eugen <strong>of</strong>f Cape Arkona later that day. This was to be <strong>Bismarck</strong>’s first operational<br />

mission. <strong>The</strong> purpose <strong>of</strong> the sortie was to attack British convoy shipping in the North Atlantic.<br />

<strong>The</strong> German ships eluded British forces until detected by HMS Suffolk at 1922 on 23 May during<br />

their attempt to break out into the North Atlantic through the Denmark Strait, between Iceland<br />

and Greenland.<br />

Hood was the largest warship in service in the Royal Navy in 1941. This beautiful ship, completed at<br />

the end <strong>of</strong> World War I, was typical <strong>of</strong> battle cruisers <strong>of</strong> that era, with high speed attained at the cost<br />

<strong>of</strong> inferior armor protection. Hood had adequate side armor protection, but her inferior horizontal<br />

protection doomed the ship during her brief engagement with <strong>Bismarck</strong>.<br />

4

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> newly-commissioned Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales and the older battle cruiser Hood engaged<br />

<strong>Bismarck</strong> early on the morning <strong>of</strong> 24 May 1941. Hood was hit and destroyed only 9 minutes<br />

after opening fire.<br />

Hood was utterly destroyed by the fifth salvo fired by <strong>Bismarck</strong>. A single 380-mm shell,<br />

possibly two, did the job. This was the consequence <strong>of</strong> stunningly accurate gunnery coupled<br />

with a flawed protective system <strong>−</strong> Hood was the last <strong>of</strong> the World War One-era battle cruisers,<br />

ships designed and built with an emphasis on speed and gun power at a time when such could<br />

only be achieved by sacrificing protection.<br />

Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales managed to hit <strong>Bismarck</strong> with three 356-mm shells, two <strong>of</strong> which caused serious<br />

damage and the loss <strong>of</strong> critical fuel 5 . (In turn, the British battleship was damaged by seven shell hits,<br />

four 380-mm from <strong>Bismarck</strong> and three 203-mm from Prinz Eugen.)<br />

Although the Hood design was modified to marginally improve her armor protection, the<br />

ship remained fatally vulnerable to long-range, plunging shellfire from heavy guns. (<strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Bismarck</strong>’s modern 380-mm guns fired 800-kilogram shells at a substantially higher muzzle<br />

velocity than the older 381-mm guns on the Hood. <strong>The</strong> German guns out-ranged the Hood’s<br />

5 This was confirmed during an extensive correspondence with two <strong>of</strong>ficers who served on Prince <strong>of</strong><br />

Wales, the spotting <strong>of</strong>ficer, CDR Arthur Skipwith (RN, Ret.) and the gunnery <strong>of</strong>ficer, CAPT Colin<br />

McMullen (RN, Ret.). CDR Skipwith recalled that he had his binoculars trained on <strong>Bismarck</strong> during the<br />

entire engagement and was able to follow the fall <strong>of</strong> shot for each salvo fired from his ship. At no time<br />

did he note the fall <strong>of</strong> any rounds fired by Hood.<br />

5

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

guns by more than 5,000 meters.) Painfully aware <strong>of</strong> the vulnerability <strong>of</strong> the Hood, the British<br />

were attempting to close the range and lessen the risk <strong>of</strong> destruction resulting from plunging fire.<br />

Less than ten minutes after opening fire, Hood blew up and sank, destroyed by 381-mm shellfire<br />

which penetrated to and detonated her magazines.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ammunition on Hood was destroyed by deflagration <strong>−</strong> intense burning (<strong>of</strong> some 112<br />

tons <strong>of</strong> cordite) with no means to dissipate its energy vertically or horizontally <strong>−</strong> which wrecked<br />

the Hood’s hull structure, causing the ship to break apart into two sections before beginning its<br />

plunge to the sea bed.<br />

A KEY HIT ON THE BISMARCK’s BOW<br />

Abeam <strong>of</strong> the capstans on the forecastle <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> is a large oblique-shaped hole in the<br />

starboard side, above the water line and Batteriedeck 6 and forward <strong>of</strong> the 60-mm splinter belt. It<br />

occurs just above the forward edge <strong>of</strong> a faded painted fake bow wave. <strong>The</strong> hole is clearly bent<br />

outward, apparently from the effects <strong>of</strong> a shell passing through the ship from the port side 7 . An<br />

elongated hole in the deck above was first thought to be the entry hole for this round, but careful<br />

measurement indicates the two holes are unrelated.<br />

<strong>The</strong> entry hole on the port side was not imaged, as there were a number <strong>of</strong> shell holes<br />

noted in the area where the shell was believed to have entered. <strong>The</strong> exit hole is consistent with a<br />

trajectory through the bow with an angle <strong>of</strong> fall <strong>of</strong> about 15 degrees and a shell path from astern.<br />

This is consistent with the expected angle <strong>of</strong> fall for a shell fired by Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales at a range <strong>of</strong><br />

about 16,000 meters <strong>−</strong> refer to Table 2.<br />

Table 2<br />

Range Table Data for the 356-mm Gun 8<br />

Range Angle <strong>of</strong> Fall Striking Velocity<br />

13,720 meters 11.5 degrees 526 meters per second<br />

18,290 meters 18.2 degrees 476 meters per second<br />

<strong>The</strong> shell’s path was an oblique one from port to starboard across Compartments XX and<br />

XXI; the second, third, and fourth watertight compartments aft <strong>of</strong> the forward perpendicular<br />

(XX, XXI, and XXII) were damaged by fragments caused by the passage <strong>of</strong> this heavy projectile<br />

through the ship. <strong>The</strong> entry hole is above the Batteriedeck, while the exit hole, above that deck<br />

or near that deck’s intersection with the side shell. <strong>The</strong> plating around the exit hole is bent<br />

outward. <strong>The</strong> condition <strong>of</strong> the exit hole in the <strong>Bismarck</strong>’s starboard bow supports the judgment<br />

that the shell passed through the ship without exploding 9 .<br />

Compartments XX and XXI are roughly centered on the fore capstans, which correspond<br />

perfectly to the exit hole. Since the exit hole was slightly above the waterline but was within the<br />

bow wave, water flowed in and eventually flooded compartments on the Upper, Middle and<br />

Lower Platform Decks. <strong>The</strong> ship’s trim down by the bow aggravated this problem. <strong>The</strong> reserve<br />

oil tanks were located in way <strong>of</strong> the shell trajectory, but below the Middle Platform Deck. Hence<br />

we believe that none <strong>of</strong> the reserve tanks were affected by this shell’s trajectory. If there was a<br />

6 This is the Second Deck in the US Navy.<br />

7 LT Gerhard Junack mentioned in correspondence with William Garzke that the shell passed through the<br />

ship without exploding. We believe it may have detonated in the water adjacent to the ship.<br />

8 John Campbell. Naval Weapons <strong>of</strong> World War Two. London: Conway Maritime Press, Ltd., 1985.<br />

9 Admiral Lütjens reported this in a message after the battle was over.<br />

6

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

loss <strong>of</strong> fuel in this area <strong>of</strong> the ship, then it must have come from shell or ship fragments that<br />

severed pipes to these tanks and damaged structure in the deck or platform over these tanks.<br />

Such damage would mean that the shell may have exploded within the bow structure in the<br />

vicinity <strong>of</strong> the exit hole (which appears unlikely) or more probably from fragments associated<br />

with the shell’s passage through the ship.<br />

It should be noted that when <strong>Bismarck</strong> refueled for this mission on 18 May, a fuel hose<br />

broke. Since time was spent in cleaning up the spill, the reserve fuel oil tanks were probably the<br />

last ones that would be filled. Inexplicably, Admiral Lütjens did not complete the refueling<br />

evolution after the loss <strong>of</strong> time resulting from the parted fuel hose incident. <strong>Bismarck</strong> left<br />

Gotenhafen (now Gdynia) with 200 tons <strong>of</strong> fuel less than full load capacity.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se reserve fuel tanks were intended for <strong>Bismarck</strong>’s consorts. <strong>The</strong> pump room for<br />

them was located outside the armored citadel. In an emergency, <strong>of</strong> course, this fuel could have<br />

been used by the battleship. To retrieve the oil in the reserve oil tanks, the <strong>Bismarck</strong>’s damage<br />

control team devised a plan to run a refueling hose over the main deck to the forward tanks, so<br />

the problem was isolation, not rupture <strong>of</strong> these tanks. Observers aboard Prinz Eugen reported oil<br />

on both sides <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong>'s wake. Some <strong>of</strong> the reserve oil tanks could have been holed by<br />

fragments caused by this hit in the bow.<br />

<strong>The</strong> damage in Compartment XXI was examined by LT Karl-Ludwig Richter, second engineer<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficer <strong>of</strong> Damage Control Central. Richter noted that there was about a meter <strong>of</strong> water on the<br />

Batteriedeck level 10 . <strong>The</strong> main bulkhead between Compartments XX and XXI and<br />

Compartments XXI and XXII were holed and no longer watertight. A gaping hole about a meter<br />

in diameter was torn in the ship's starboard hull and another hole <strong>of</strong> similar size was made in the<br />

port side plating. This was confirmed by James Cameron’s survey. <strong>The</strong> 356-mm shell passed<br />

through Compartments XXI and XXII, with fragments rupturing two emergency fuel tanks and<br />

flooding the forward pump room, where manifolds to the fuel and ballast tanks were located.<br />

<strong>Bismarck</strong> began to lose what little fuel remained in those forward tanks. <strong>The</strong> battleship now had<br />

as much as 1,000 tons <strong>of</strong> seawater in her bow.<br />

<strong>The</strong> question as to how much fuel oil was lost from this area <strong>of</strong> the ship has never been<br />

determined. <strong>The</strong> reserve fuel tanks were located below the Middle Platform Deck with a pipe<br />

tunnel running along the centerline <strong>of</strong> the ship to port. Was a fuel line, air vent piping, or<br />

sounding tube severed? Did downflooding prevent access to valves, manifolds, or pumps used to<br />

remove or stow fuel? Did downflooding in vent pipes, sounding tubes, or fill piping contaminate<br />

the fuel? Another visit to the wreck to examine the inner spaces may resolve this enigma.<br />

Counter-flooding voids, provided to allow counter-flooding to compensate for list and<br />

trim due to damage below the waterline and resultant flooding, were filled to starboard,<br />

according to information provided to author William Garzke by Seaman Josef Statz 11 .<br />

10 From German Battleship <strong>Bismarck</strong>, Interrogation <strong>of</strong> Survivors, CB4051 (24), page 13. Although LT<br />

Richter was not a survivor, several survivors who were damage control specialists recalled his report <strong>of</strong><br />

the damage in the bow.<br />

11 Josef Statz, with relevant draftsman experience (Lübeck Shipyard) prior to his naval service, was<br />

assigned to Damage Control Central, which was supervised by the Executive Officer, CDR Hans Oels.<br />

7

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

This depiction <strong>of</strong> the subdivision numbering scheme on <strong>Bismarck</strong> will help in visualizing and locating<br />

the damage described in this paper.<br />

ANOTHER DAMAGING HIT AMIDSHIPS ON THE PORT SIDE<br />

Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales achieved another important hit, abeam <strong>of</strong> the forward superstructure. A<br />

356-mm shell with an underwater trajectory penetrated the port side hull plating below the<br />

termination <strong>of</strong> the armor belt and passed into the side protection system. <strong>The</strong> shell exploded near<br />

the main transverse bulkhead between Compartments XIII and XIV, detonating with great force<br />

against the 45-mm torpedo bulkhead outboard <strong>of</strong> Electrical Power Station No. 4. This detonation<br />

also affected the watertight boundaries between that space and the adjacent port No. 2 Boiler<br />

Room, as well as the inboard auxiliary boiler room inboard in Compartment XIV. Shell splinters<br />

also passed into double bottom tanks and wing fuel bunkers in Compartment XIV, causing the<br />

eventual flooding <strong>of</strong> those tanks and contaminating the feed water in the double bottom <strong>of</strong><br />

Compartment XIV. <strong>The</strong> damaged wing tank in Compartment XIV also began leaking oil into the<br />

sea, as salt water gradually replaced those tanks’ contents. It is believed that the shell and<br />

structural fragments did not reach the double bottom below Boiler Room No. 2.<br />

British observers on the Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales saw a burst <strong>of</strong> black smoke come from the<br />

<strong>Bismarck</strong>’s funnel at this time. Some German survivors recalled a slight shock response from<br />

this hit.<br />

8

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

Two views <strong>of</strong> the exit hole for the key hit achieved by Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales during her engagement with<br />

<strong>Bismarck</strong>. This hole is on the starboard side, just above the forward edge <strong>of</strong> the false bow wave.<br />

This hole was below the bow wave created by the battleship at 28 knots, once the ship trimmed down<br />

by the bow. After this damage and the hit in Compartment XIV, fuel trailed in the <strong>Bismarck</strong>’s wake.<br />

9

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

According to survivors, large cracks appeared in the welded seams in the outboard<br />

strakes <strong>of</strong> the main transverse bulkhead, which was also the forward boundary <strong>of</strong> Port Boiler<br />

Room No. 2 in Compartment XIII. Seawater seeped through these cracks and caused gradual<br />

flooding <strong>of</strong> this boiler room. A damage-control team attempted to seal <strong>of</strong>f these leaks with<br />

hammocks, but their efforts only slowed the seepage. <strong>The</strong> boiler room was back in operation for<br />

a short time. Boiler III was lighted, while Boiler IV was salt-contaminated and had to be shut<br />

down because there was a real danger <strong>of</strong> saltwater intrusion into the feed water system. By midafternoon,<br />

Boiler III also had to be shut down and the space was evacuated. Fuel from the<br />

damaged wing tanks in Compartment XIV was leaking into the sea.<br />

Soon after the action with Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales ended, a damage-control team attempted to<br />

seal <strong>of</strong>f the leaks in the 45-mm torpedo bulkhead on the portside in Compartment XIV with<br />

hammocks and mating, but their efforts only slowed the seepage into the boiler room. Eventually<br />

the boiler room was evacuated after the water became chest deep.<br />

Steam from other boilers was rerouted to the turbine in the port engine room. Splinters<br />

from the exploding shell also severed a main steam line in the No. 4 Turbo-Generator Room,<br />

scalding five <strong>of</strong> its occupants and necessitating the shutdown <strong>of</strong> the generators. <strong>The</strong> Turbo-<br />

Generator Room also flooded 12 . <strong>The</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> this electrical generating station was not serious,<br />

because the power supply <strong>of</strong> German battleships was so conceived that either the forward or the<br />

after station could supply the battle circuit load individually (i.e., the ship had 100% reserve<br />

battle load power).<br />

<strong>The</strong> bow flooding, coupled with the displacement <strong>of</strong> fuel oil in Compartment XIV and<br />

subsequent flooding <strong>of</strong> spaces there, caused the battleship to trim 1.5 meters by the bow, with a<br />

three-degree list to port <strong>−</strong> not nine degrees previously estimated. <strong>The</strong>se hits came around 0605<br />

(after Hood had sunk). <strong>The</strong> combination <strong>of</strong> trim and list caused the starboard propeller blades to<br />

break the water surface.<br />

Soon after the action with Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales ended, a damage-control team attempted to<br />

seal <strong>of</strong>f the leaks in the 45-mm torpedo bulkhead on the portside in Compartment XIV with<br />

hammocks and mating, but their efforts only slowed the seepage into the boiler room. Eventually<br />

the water was chest deep. <strong>The</strong>re was a real danger <strong>of</strong> saltwater intrusion into the feed water<br />

system. <strong>The</strong> crew managed to get Port Boiler Room No. 2 temporarily back in operation. Boiler<br />

III was back in service, although while Boiler IV was salt contaminated and had to be shut down.<br />

By mid-afternoon, however, Boiler III also had to be shut down and the boiler room was<br />

evacuated. Shell splinters also passed into double bottom tanks and wing fuel bunkers, causing<br />

the eventual flooding <strong>of</strong> that tankage and contaminating the fuel.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se reserve fuel tanks were intended for <strong>Bismarck</strong>’s consorts. <strong>The</strong> pump room for<br />

them was located outside the armored citadel. In an emergency, <strong>of</strong> course, this fuel could have<br />

been used by the battleship. To retrieve the oil in the reserve oil tanks, the <strong>Bismarck</strong>’s damage<br />

control team devised a plan to run a refueling hose over the main deck to the forward tanks, so<br />

the problem was isolation, not rupture <strong>of</strong> these tanks. Some <strong>of</strong> the reserve oil tanks could have<br />

been holed by fragments caused by this hit in the bow. Fuel leaking into the sea would have<br />

flowed along the side <strong>of</strong> the ship, being mixed by the turbulence in the wake, convincing<br />

observers aboard Prinz Eugen that there was oil on both sides <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong>'s wake.<br />

12 Midshipman Hans-Georg Stiegler, a naval constructor in training, was assigned to the electrical shop.<br />

He recalled that this compartment was successfully dewatered the next day.<br />

10

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

ADMIRAL LÜTJENS’ DAMAGE REPORT TO NAVAL GROUP NORTH<br />

Admiral Lütjens’ report to Naval Group North, based on damage assessments by<br />

<strong>Bismarck</strong>’s damage control teams, is most revealing:<br />

"Two heavy hits. One in Compartments XIII-XIV with the loss <strong>of</strong> electrical station 4; port<br />

boiler room is taking water, which we can control. Second hit Compartment XX-XXI in<br />

the forecastle. Shell entered port, exited starboard above armor deck. Third hit on a<br />

boat, <strong>of</strong> no concern."<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> the port list was due to the flooded No 4 turbo-generator room, the port No. 2<br />

Boiler Room, fuel tanks outboard <strong>of</strong> these spaces, and some <strong>of</strong> the port counterflooding tanks in<br />

Compartments XIII-XIV. Lütjens’ report about the shell hit forward that exited the starboard<br />

side shell and the size <strong>of</strong> the hole would indicate that the shell did not explode within the ship.<br />

However, its penetration through ship structure did create fragments that had sufficient energy to<br />

penetrate through the deck structure to the port reserve fuel oil tanks and perhaps the pipe tunnel.<br />

<strong>The</strong> starboard tanks were probably intact. What fuel was left in those tanks would have mixed<br />

with seawater and because the exit hole was below the bow wave created by the ship’s forward<br />

motion and trim the fuel/seawater mix would exit from the starboard and port side. <strong>The</strong> flooding<br />

<strong>of</strong> the pipe tunnel and port fuel reserve tanks that were partially empty would also contribute to<br />

the port list, which reached about 4.5 degrees.<br />

What is significant is that two shells fired at a range <strong>of</strong> 15,000-16,000 meters by the 356mm<br />

guns <strong>of</strong> Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales materially damaged <strong>Bismarck</strong>, leading to the eventual decision to<br />

abort the <strong>Bismarck</strong>’s commerce-raiding mission. It would not be possible to conceal <strong>Bismarck</strong>’s<br />

presence at sea with fuel leaking into the sea. This gunfire damage is important, because it<br />

clearly documents the effectiveness <strong>of</strong> main armament-caliber plunging fire at long range. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

are the precise conditions <strong>of</strong> the earliest part <strong>of</strong> the final battle on 27 May, but most definitely<br />

were not the situation during the latter part <strong>of</strong> that battle, when Rodney had moved to starboard<br />

(firing at low angles <strong>of</strong> elevation at less than 3,700 meters) and King George V was also firing at<br />

close range from port.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se two shell hits 13 achieved by Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales occurred about the time Hood<br />

sustained her fatal damage, approximately 0600. Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales was about 16,000 meters<br />

distant at the time, eventually closing to 14,500 meters. Angle <strong>of</strong> fall <strong>of</strong> both shells would have<br />

been between 12-15 degrees. It is interesting that the descent angle was sufficient to allow one<br />

shell which fell short to follow an underwater trajectory, being deflected and substantially<br />

slowed by the water, to pass under the armor belt and enter the hull abeam <strong>of</strong> the bridge. It is<br />

unlikely the latter projectile could have crossed the width <strong>of</strong> the Batteriedeck at that angle <strong>of</strong> fall,<br />

unless it ricocheted <strong>of</strong>f the deck before it exploded against the shell plating (a possibility). <strong>The</strong><br />

level <strong>of</strong> the exit hole for the forward shell hit, however, seems to correspond to Zwischendeck<br />

level, not the Batteriedeck level.<br />

After the engagement with Hood and Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales, the ship’s engineers suggested<br />

slowing <strong>Bismarck</strong> and heeling the ship once to port and then to starboard and welding on steel<br />

13 An analysis <strong>of</strong> the gunnery report <strong>of</strong> Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales and an extensive correspondence by William<br />

Garzke with then-CDR Colin McMullen, the gunnery <strong>of</strong>ficer, and LCDR Arthur Skipwith, spotting<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficer, confirms it was the Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales (not Hood) that achieved these two hits. Gunners on the new<br />

British battleship had only two weeks <strong>of</strong> gunnery drills, NONE firing live rounds.<br />

11

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

patches over the entrance and exit holes to repair the damage at the bow. <strong>The</strong> plates to cover the<br />

entrance and exit holes were cut and ready to install. This plan was rejected by Admiral Lütjens,<br />

as it would involve slowing the ship and creating a list to port or starboard to permit the repairs.<br />

From pictures, it appears the bow was down 1.5 to 2.5 meters, so one could anticipate a<br />

commensurate rise at the stern. In fact, the underside <strong>of</strong> the stern was clear <strong>of</strong> the water in one<br />

picture. Survivor accounts say the starboard screw was running with its blade tips out <strong>of</strong> the<br />

water after the 24 May battle.<br />

Captain Lindemann ordered the flooding <strong>of</strong> starboard voids in Compartments II and III in<br />

the stern to restore trim and list, but it is unknown how effective this was. Presumably, trim was<br />

not fully restored. Unfortunately, these counter flooding measures increased draft and decreased<br />

the overall freeboard. This could have been a factor in later events, since a lower freeboard<br />

meant less reserve buoyancy. A lower freeboard made it more difficult to hit below the main<br />

side belt when firing at close range. Close-range gunfire is more likely to have shells ricochet <strong>of</strong>f<br />

the water surface, substantially reducing the likelihood <strong>of</strong> shells having an underwater trajectory.<br />

THE CHASE ─ 24 May through 26 May 1941<br />

<strong>Bismarck</strong> was hit by one torpedo dropped by a Swordfish torpedo bomber launched from<br />

HMS Victorious the evening <strong>of</strong> 24 May. This contact detonation, on the starboard side in way <strong>of</strong><br />

the 320-mm main side belt armor was not a factor in the ultimate destruction <strong>of</strong> the German<br />

This minor damage on the starboard side amidships was caused by an aerial torpedo the evening <strong>of</strong> 24<br />

May 1941. <strong>The</strong> torpedo detonated against the 320-mm main side belt armor, failing to penetrate. <strong>The</strong><br />

gouges in the upper (145-mm) and main side belts are from hits by 203-mm or smaller caliber shells<br />

that did not penetrate.<br />

12

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

battleship. Minor flooding resulted, as the belt armor displaced inboard and damage control<br />

packing in way <strong>of</strong> the shell hit in way <strong>of</strong> Compartments XIII and XIV was loosened.<br />

Overnight, <strong>Bismarck</strong> broke contact with her British pursuers and headed for shelter and<br />

major repair facilities at the Penhoet-Loire Shipyard in St. Nazaire, France. <strong>The</strong> heavy cruiser<br />

Prinz Eugen was detached to continue the originally-planned commerce-raiding mission into the<br />

Atlantic. After an interval <strong>of</strong> 31 hours, the German battleship was spotted by a British Catalina<br />

aircraft, piloted by an American naval aviator, ENS Leonard B. (“Tuck”) Smith. 14<br />

This sighting permitted aircraft from HMS Ark Royal to attack the German ship during<br />

the evening <strong>of</strong> 26 May. If the Germans were not diverted from their course to France in the next<br />

few hours, they would soon be within range <strong>of</strong> friendly shore-based aircraft and likely out <strong>of</strong><br />

danger, despite the best efforts <strong>of</strong> the men and ships <strong>of</strong> the Royal Navy.<br />

At this time, the light cruiser Sheffield was shadowing the German ship. Fortunately, as<br />

matters turned out, the Royal Navy aviators, unaware <strong>of</strong> the presence <strong>of</strong> the friendly cruiser,<br />

attacked one <strong>of</strong> their own ships! This near-tragic incident was <strong>of</strong> enormous importance, since the<br />

men on the cruiser reported that those torpedoes directed at their ship detonated prematurely. It<br />

was judged that the magnetic-fused detonators fitted to the torpedoes were defective.<br />

When a last-gasp attempt by Swordfish torpedo bombers to stop <strong>Bismarck</strong> was launched<br />

later on the afternoon <strong>of</strong> the 26 th <strong>of</strong> May, more reliable contact fuses were installed. <strong>The</strong><br />

torpedoes were also set for a relatively shallow running depth, about three meters. This attach<br />

was successful, scoring three torpedo hits. Two hits amidships caused relatively inconsequential<br />

damage ─ minor inboard flooding was caused by a hit on the port side, in way <strong>of</strong> Compartment<br />

VII. <strong>The</strong> detonation severed the degaussing system cable in the vicinity. <strong>The</strong> damaged cable<br />

can be seen adjacent to the torpedo hole. A second hit on the starboard side in way <strong>of</strong><br />

Compartment VII caused some flooding, which was confined to the side protective system.<br />

Unfortunately for the Germans, the third torpedo detonated in the stern near the starboard<br />

rudder. This damage caused the instantaneous and devastating loss <strong>of</strong> steering control.<br />

THE MORTAL TORPEDO HIT<br />

Identification <strong>of</strong> torpedo hits was extremely difficult except for the mortal torpedo hit in<br />

way <strong>of</strong> the rudders. It is very important to remember that water was frequently forced out by the<br />

phenomenon <strong>of</strong> hydraulic outburst, discussed later in this paper, even where there were no preexisting<br />

holes. We believe this phenomenon accounts for the majority <strong>of</strong> the damage to the<br />

lower hull. Jim Cameron’s team clearly imaged an area on the port side where the lower hull<br />

shell was detached from the main side belt and the plating forced outward, but the separation<br />

attenuated to zero both forward and aft, and there was absolutely no evidence <strong>of</strong> torpedo or shell<br />

damage in the vicinity, thus indicating the start <strong>of</strong> the hydraulic outburst process which was<br />

stopped before the lower hull section completely detached. <strong>The</strong> forensic evidence at the wreck<br />

site strongly supports the conclusion that any pre-existing torpedo or shell damage acted to stop<br />

the propagation <strong>of</strong> cracks running along the joint between main side belt armor and the lower<br />

hull shell, probably by acting as a relief valve to vent the overpressure. When a crack is running<br />

in a piece <strong>of</strong> plexi-glass, for example, a hole is drilled ahead <strong>of</strong> the crack and that measure halts<br />

the crack propagation at the hole. We believe what is seen on <strong>Bismarck</strong> is a similar mechanism<br />

on a much larger scale. Almost all the damage that the team has seen from the May 2002 survey<br />

14 As related by CAPT Leonard Smith (USN, Ret.) in correspondence with author William Garzke.<br />

13

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

can be explained in this manner, including the explosion damage starboard in way <strong>of</strong> Turret<br />

Dora. What is seen there is an outburst propagation which ended at a pre-existing torpedo hole.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re may be other, similar instances <strong>of</strong> this, but the evidence is masked by sediment.<br />

<strong>Bismarck</strong> had a slight list to port before the Swordfish aircraft made their torpedo attacks<br />

during the evening <strong>of</strong> 26 May. A review <strong>of</strong> the British airmen’s report <strong>of</strong> the attack is<br />

inconclusive as to the number <strong>of</strong> torpedo hits or where they may have struck the battleship. As<br />

has been mentioned earlier, German survivor testimony is rather conclusive that there were two<br />

torpedo hits sustained amidships, one on either side 15 .<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the last attacking planes reported <strong>Bismarck</strong> was in a port turn. Several survivors<br />

(LCDR Baron von Müllenheim-Rechberg, and Apprentice Seamen Bruno Rzonca and Georg<br />

Herzog) observed two low-flying aircraft making their approach from starboard aft. With the<br />

ship turning to port, the two aircraft made a turn toward <strong>Bismarck</strong> and dropped their torpedoes<br />

very close to the stern 16 . <strong>The</strong>y then over-flew <strong>Bismarck</strong> in their successful effort to escape.<br />

Herzog noted that the 105-mm guns couldn’t depress their barrels low enough to engage the<br />

aircraft as they approached 17 .<br />

During the last torpedo attack that came from astern, two torpedoes quickly approached<br />

<strong>Bismarck</strong>. One missed. <strong>The</strong> other torpedo continued on its fateful path toward the stern. <strong>The</strong>re<br />

are three plausible scenarios regarding the location <strong>of</strong> its detonation:<br />

○ It exploded against the trailing edge <strong>of</strong> the starboard rudder.<br />

○ It exploded to the starboard side <strong>of</strong> the centerline between the two rudders.<br />

○ It exploded in the wake <strong>of</strong> centerline propeller.<br />

We believe that this torpedo passed under the stern and that the wake from the propellers<br />

forced it upwards against the underside <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong>’s stern plating, between the two rudders,<br />

whereupon it exploded with tremendous force. Based on the nature <strong>of</strong> the damage to the hull, we<br />

believe that the torpedo actually exploded to the starboard side <strong>of</strong> the centerline, destroying a<br />

large amount <strong>of</strong> structure, including the structural support for the starboard rudder stock. <strong>The</strong><br />

venting force <strong>of</strong> the torpedo explosion was carried to the port side, causing the port rudder stock<br />

to fail. None <strong>of</strong> the British airmen observed the characteristic water plume <strong>of</strong> an exploding<br />

torpedo in the stern area. This is strong evidence that almost all <strong>of</strong> the force <strong>of</strong> the exploding<br />

torpedo was vented against and into <strong>Bismarck</strong>’s overhanging stern structure.<br />

<strong>The</strong> torpedo hit or exploded under the stern. Its explosion also caused the failure <strong>of</strong> a<br />

large portion <strong>of</strong> the trailing edge <strong>of</strong> the starboard rudder (about 25-50% <strong>of</strong> the total rudder area).<br />

<strong>The</strong> starboard rudder stock and the rudder itself were pushed forward and towards the centerline<br />

15<br />

This information was provided by Baron von Müllenheim-Rechberg during a discussion aboard the<br />

heavy cruiser Dorsetshire after his recovery, as related to authors William Garzke and Robert Dulin<br />

during an interview in Annapolis, Maryland during September 1980. <strong>The</strong> Baron, an artillery specialist,<br />

was the fourth gunnery <strong>of</strong>ficer on <strong>Bismarck</strong>, with a rank <strong>of</strong> LT. Seaman Josef Statz, who was assigned to<br />

Damage Control Central, provided Mr. Garzke a detailed flooding diagram <strong>of</strong> the ship, further confirming<br />

this information.<br />

16<br />

Baron von Müllenheim-Rechberg in his book, Battleship <strong>Bismarck</strong>, A Survivor’s Story, commented<br />

that the torpedo was dropped from only 20 meters astern. That estimate cannot be correct, for that short a<br />

distance would not allow the torpedo to arm. Perhaps the distance was 200 meters.<br />

17<br />

<strong>The</strong> extreme motions <strong>of</strong> the ship in the sea way, coupled with the port list and the trim down by the<br />

bow, may have contributed to this difficulty.<br />

14

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

about 3 meters, causing the lower portion <strong>of</strong> the rudder’s leading edge to enter the turning circle<br />

<strong>of</strong> the spinning center propeller.<br />

<strong>The</strong> most interesting find during the 2002 Cameron Expedition was the damage sustained<br />

by the center propeller. Only one <strong>of</strong> the three blades is visible, while the other two are buried in<br />

sediment. <strong>The</strong> centerline propeller gouged the rudder repeatedly until finally there was no<br />

contact. Striations were found in the forward and after edges <strong>of</strong> the exposed propeller blade.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se marks are consistent with repeated strikes <strong>of</strong> the rudder by the rotating propeller. <strong>The</strong> tips<br />

<strong>of</strong> the three blades were damaged, and part <strong>of</strong> one blade was torn away. Most <strong>of</strong> one blade from<br />

the centerline propeller was found embedded in the lower leading edge <strong>of</strong> what remains <strong>of</strong> the<br />

starboard rudder. Whether the blades were bolted to the propeller hub or the propeller was a<br />

one-piece manganese-bronze casting, we believe this blade fractured at the root <strong>of</strong> the blade near<br />

the hub. <strong>The</strong> starboard rudder was found displaced forward <strong>of</strong> the plane <strong>of</strong> the centerline<br />

propeller. This displacement occurred either during the explosion event, due to stern slamming<br />

prior to the sinking, or during the sinking event. <strong>The</strong> broken propeller blade is now more than a<br />

meter aft <strong>of</strong> the visible centerline propeller blade 18 .<br />

This is a view <strong>of</strong> the starboard rudder and the centerline propeller, as seen from the port side<br />

<strong>of</strong> the wreck. Note that one <strong>of</strong> the three blades <strong>of</strong> the centerline propeller is projecting above<br />

the sediments below the remains <strong>of</strong> the rudder. Note the outer portion <strong>of</strong> its blade is chipped.<br />

It must have taken quite a force to break <strong>of</strong>f such a blade. We are not sure whether<br />

<strong>Bismarck</strong> actually had single-piece propellers or propellers with removable blades. <strong>The</strong> drawing<br />

set shows both types <strong>of</strong> installation. We suspect that Blohm and Voss put a hub with removable<br />

18 All <strong>of</strong> these conclusions are based on stereoscopic HD imaging done from the Mir submersibles and on<br />

an extremely close ROV survey done with the “JAKE” spiderbot ROV, both during the May 2002<br />

expedition. <strong>The</strong> “JAKE” ROV was also piloted inside the steering gear room.<br />

15

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

blades on first, with slotted bolt holes to allow the propeller to be adjusted slightly for maximum<br />

efficiency, then <strong>−</strong> once the best position was found from tests in the Baltic in the fall <strong>of</strong> 1940 <strong>−</strong><br />

manufactured and installed solid, one-piece propellers to replace the experimental ones.<br />

In his recollection <strong>of</strong> leaving the center engine room after placing scuttling charges, LT<br />

Gerhard Junack advised author Bill Garzke, Jochen Brennecke 19 , and Dr. Oscar Parkes 20 that he<br />

left the engine room around 1010 with shining lights and a slowly turning shaft. For that shaft to<br />

keep turning, either the coupling in the shafting was parted by the jamming <strong>of</strong> the rudder into the<br />

center propeller, the keys holding the center propeller to the shaft failed in shear, or the propeller<br />

was able to keep turning once the intact portions <strong>of</strong> the three blades were free <strong>of</strong> the rudder<br />

structure.<br />

<strong>Bismarck</strong> underwent an extensive stay in the Blohm & Voss Shipyard from December<br />

1940 until March 5, 1941. We have seen no photographs taken <strong>of</strong> the propellers during that stay<br />

<strong>−</strong> views taken in July 1940 cannot answer the question as to what was fitted when the battleship<br />

sortied for combat. It is very probable that single-piece propellers were fitted during that final<br />

availability. <strong>The</strong> dramatic discovery <strong>of</strong> the embedded blade in the rudder gives a new insight<br />

into the condition <strong>of</strong> the propellers and rudders at the time <strong>of</strong> the sinking <strong>of</strong> the battleship. Bolted<br />

blades are used today in controllable pitch propellers in FFG-7 and DDG-51 class ships, with<br />

hefty bolts.<br />

Until the James Cameron May 2002 Expedition, the seriousness <strong>of</strong> damage to the rudders<br />

was unknown. Photography <strong>of</strong> the underside <strong>of</strong> the hull revealed that the rudder stock for the<br />

port rudder had fractured. Did the force <strong>of</strong> the torpedo explosion bend this rudder, which was<br />

already canted outboard about 8 degrees, further to port causing it to contact the port propeller?<br />

<strong>The</strong> answer to that question is “no”, because the port propeller shows no sign <strong>of</strong> damage. Did the<br />

subsequent slamming <strong>of</strong> the hull in the heavy seas lead to the failure <strong>of</strong> the rudder stock through<br />

the forces <strong>of</strong> accelerated fatigue? <strong>The</strong> answer can never be known with certainty.<br />

In the meantime, the light cruiser Sheffield reported that <strong>Bismarck</strong> was heading to the<br />

northeast at a slow speed. Sea conditions hampered the Sheffield’s efforts to determine the nature<br />

<strong>of</strong> the damage caused by the torpedo attack. Due to her port turn, <strong>Bismarck</strong> closed range and<br />

then opened fire with her 380-mm guns in a brief engagement. Before the cruiser could open the<br />

range, <strong>Bismarck</strong>’s gunfire disabled Sheffield’s radar, caused minor fragment damage, and<br />

inflicted several casualties. This incident reminded the British that the <strong>Bismarck</strong> remained a<br />

formidable adversary, even if damaged and apparently unable to escape.<br />

Captain Lindemann ordered the ship to be slowed so that assessment <strong>of</strong> the damage in the<br />

stern could begin. He ordered two <strong>of</strong> his best damage control personnel, LT Gerhard Junack and<br />

LTJG Hermann Giese, to the area to determine the nature <strong>of</strong> the damage and to commence the<br />

needed temporary repairs. <strong>The</strong>ir efforts had to be halted at times, as Admiral Lütjens, Captain<br />

Lindemann, and CDR Oels wanted reports regarding the efforts to restore the steering function.<br />

Oels also sent two divers to the area to determine what damage occurred in the steering gear<br />

rooms. Lowering divers over the side was discussed, but sea conditions were causing the stern to<br />

rise and fall with such force that an accurate inspection was impossible and might have caused<br />

the death <strong>of</strong> the divers,as well. Attempts to steer the ship with the propellers were unsuccessful,<br />

due to the position <strong>of</strong> the starboard rudder in the race <strong>of</strong> the center propeller. <strong>Bismarck</strong> was<br />

doomed.<br />

19 Schlachtschiffe <strong>Bismarck</strong>, Kohlers Verlag, 1960, page 361.<br />

20 Dr. Oscar Parkes’ paper on <strong>Bismarck</strong> in the 1948 Transactions <strong>of</strong> the Royal Institution <strong>of</strong> Naval<br />

Architects. Dr. Parkes did not name the source except as a survivor.<br />

16

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> edge <strong>of</strong> the damaged starboard rudder is shown below the hull opening for the fractured<br />

port rudder stock (arrow.)<br />

<strong>The</strong> damaged starboard rudder with the embedded centerline propeller blade.<br />

17

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

This drawing, showing the proximity <strong>of</strong> the centerline propeller to the two rudders, shows how it was<br />

possible that the damaged rudder was forced into contact with the centerline propeller.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re was no mention <strong>of</strong> the center propeller being disabled in dialog with the Baron and<br />

with LT Junack 21 , who were the senior surviving <strong>of</strong>ficers. Because <strong>of</strong> the rough sea conditions,<br />

the Germans were unaware <strong>of</strong> the damage to the centerline propeller and the seriousness <strong>of</strong> the<br />

rudder damage. <strong>The</strong>y did hear or feel banging and vibration after the torpedo explosion. As<br />

ordered by Captain Lindemann, LCDR Walter Lehmann, the battleship’s Chief Engineer 22 ,<br />

varied the propeller rotations on the three shafts in an effort to counter the effects <strong>of</strong> what they<br />

believed were jammed rudders.<br />

LCDR Lehmann called each <strong>of</strong> the <strong>of</strong>ficers in charge <strong>of</strong> the three engine rooms and told<br />

them to station a man at the forward throttle to the turbines, another at the throttle for the astern<br />

turbine, and a standby in case <strong>of</strong> an emergency, instead <strong>of</strong> manning the engine controls in each <strong>of</strong><br />

the engine rooms. This procedure was followed to respond precisely to the commands that would<br />

be given by Captain Lindemann from the bridge. According to LCDR von Müllenheim-<br />

Rechberg:<br />

21 Author Bill Garzke corresponded with CDR Junack from 1961-1975 and the Baron from 1965-1993.<br />

Bob Dulin and Bill Garzke interviewed the Baron in Annapolis, Maryland in September 1980.<br />

22 Although <strong>of</strong>ficial USN terminology is “engineer <strong>of</strong>ficer,” “chief engineer” is the most common usage.<br />

18

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

"<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong>'s hull shook noticeably as Lindemann ordered various speeds and combinations<br />

<strong>of</strong> propellers in an attempt to bring us back on course. <strong>The</strong> orders came down from the bridge in<br />

rapid succession: 'Port engines half ahead, center and starboard engines stop' - 'Port and center<br />

engines half ahead, starboard engines back slow' – ‘Port engines full ahead, starboard engines<br />

stop.' ”<br />

<strong>The</strong>se orders were carried out in the machinery spaces in violation <strong>of</strong> all routine safety<br />

procedures for waiting between "full ahead," “full astern,” or "all stop." It was a desperate effort<br />

to bring the ship back on a course away from the enemy. Severe vibrations were noted,<br />

particularly in the region <strong>of</strong> the center engine room. With the machinery space ventilation and<br />

accesses closed due to a night engagement with the British destroyers, temperatures in the boiler<br />

and engine rooms reached 50 o Centigrade <strong>−</strong> 122° Fahrenheit <strong>−</strong> with men in leather jackets! 23<br />

Efforts to restore the steering continued until the divers realized that they could not<br />

continue any damage repairs due to the swirling <strong>of</strong> water within the steering gear room. <strong>The</strong>re<br />

was some discussion <strong>of</strong> using explosives to sever the rudder shafts, but Captain Lindemann<br />

would not allow this, as he felt it would cause damage the centerline propeller, which was<br />

located very close to the rudders.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se efforts lasted for about 15 minutes until Captain Lindemann realized that any<br />

further attempts to use the propellers for steering were futile. At one point, the ship would<br />

respond and take a favorable heading, but in the next instant the rudder position and the wind and<br />

sea conditions would turn the ship around to the northwest again. Such behavior in a seaway is<br />

typical <strong>of</strong> a ship with no steering control. When Captain Lindemann tried variations in speed<br />

and combinations <strong>of</strong> propellers in an attempt to resume a course to the southeast, the <strong>Bismarck</strong>’s<br />

hull shook noticeably. It was unknown to the crew that this vibration was caused by the<br />

damaged centerline propeller.<br />

<strong>The</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> steering control caused the ship to head into the prevailing heavy seas,<br />

leading to stern slamming that might have changed the damaged rudder’s position. Since the gas<br />

bubble from the torpedo explosion was trapped under the stern and not free to vent to the water<br />

surface, as it would be at the side <strong>of</strong> the ship, the force <strong>of</strong> the torpedo explosion caused a<br />

sensation <strong>of</strong> lifting the stern. It also ripped a hole in the underside <strong>of</strong> the hull that allowed water<br />

to enter the steering gear rooms. <strong>The</strong> foundation surrounding the starboard rudder stock was<br />

very severely damaged. Since both the port and starboard rudder were cross-connected, the<br />

steering machinery was mangled and the steering system was permanently disabled. <strong>The</strong><br />

position <strong>of</strong> the damaged starboard rudder in the wake <strong>of</strong> the center propeller kept the ship in a<br />

port turn. Just after the torpedo hit occurred, the ship heeled violently to port. <strong>The</strong> sensation<br />

from that heeling was such that some survivors thought she might capsize. LT Gerhard Junack,<br />

who was in charge <strong>of</strong> the center engine room, reported that "floor plates in the center engine<br />

were moved upward about 0.5 meters 24 . Welds failed. Water poured in through the port shaft<br />

alley. <strong>The</strong> safety valve in the starboard engine room closed and the turbines were shut down or<br />

slowed.”<br />

23<br />

<strong>The</strong> Baron interviewed LT Junack to obtain this information.<br />

24<br />

<strong>The</strong> vertical displacement <strong>of</strong> the floor plates may have been caused by the damaged out-<strong>of</strong>-balance<br />

centerline propeller.<br />

19

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> stormy night <strong>of</strong> 26-27, the battleship was harassed by a series <strong>of</strong> determined but<br />

unsuccessful torpedo attacks by five destroyers. By day break on the following morning, most <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>Bismarck</strong>’s crew were physically and mentally exhausted. <strong>The</strong>se men were confronted with<br />

the likelihood <strong>of</strong> imminent death.<br />

THE FINAL BATTLE ─ 27 May, 1941<br />

<strong>Bismarck</strong> was making no more than 5 knots when the action started, unable to maneuver<br />

or take evasive action. Later, she had no forward speed due to the prevailing sea conditions. For<br />

her later salvos, Rodney closed from 18,000 to 3,700 meters, firing at virtually point-blank range<br />

by naval gunnery standards. King George V eventually closed to less than 3,700 meters, as well.<br />

<strong>The</strong> heavy sea conditions (20' swells or higher) affected gunnery accuracy, even at close range.<br />

<strong>The</strong> 356-mm and 406-mm guns had malfunctions. King George V was especially plagued by<br />

mechanical breakdowns <strong>of</strong> her heavy guns during the battle.<br />

During the morning <strong>of</strong> 27 May, the battleships Rodney and King George V, accompanied<br />

by heavy cruisers Dorsetshire and Norfolk, shelled <strong>Bismarck</strong> for a period <strong>of</strong> 92 minutes, firing a<br />

total <strong>of</strong> 2,876 shells. (See Table 3.) <strong>The</strong> German battleship’s main battery gunfire control system<br />

was disabled in the first few minutes <strong>of</strong> the gunnery engagement. All four 380-mm main battery<br />

turrets were silenced in less than 45 minutes.<br />

Table 3<br />

British Shells Fired at the <strong>Bismarck</strong> (27 May 1941)<br />

406-mm 356-mm 203-mm 152-mm 134-mm<br />

King George V --- 339 --- --- 660<br />

Rodney 380 --- --- 716 ---<br />

Dorsetshire --- --- 254 --- ---<br />

Norfolk --- --- 527 --- ---<br />

<strong>The</strong>re were hundreds <strong>of</strong> hits ranging from 134-mm to 406-mm in caliber. <strong>The</strong><br />

devastation caused by the shellfire combined with the effects <strong>of</strong> several torpedo hits to<br />

overwhelm and defeat the <strong>Bismarck</strong>, causing the ship to begin sinking due to uncontrollable<br />

progressive flooding. <strong>The</strong> German crew sped the inevitable demise <strong>of</strong> their ship by initiating<br />

scuttling measures.<br />

THE GUNNERY ENGAGEMENT ─ A DAMAGE ANALYSIS<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are several large shell entry holes that correspond to the 406-mm guns on Rodney<br />

and the 356-mm guns on King George V. <strong>The</strong>re are also many shell gouges on the 145-mm and<br />

320-mm armor belts where 203-mm, 152-mm, and 134-mm shells hit and ricocheted <strong>of</strong>f before<br />

exploding, detonated without penetrating the armor, or were disarmed by their impact. <strong>The</strong>re are<br />

numerous entry holes about the diameters <strong>of</strong> the penetrating projectiles, varying from circular to<br />

elongated ellipses, depending upon the angle <strong>of</strong> entry. <strong>The</strong>re are approximately twenty holes<br />

caused by the larger caliber shells. In a few cases, the explosion was at or just above deck level,<br />

producing a large irregular hole and a depressed area in the deck structure.<br />

20

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

DAMAGE HIGHLIGHTS<br />

○ About 0859, one <strong>of</strong> Rodney’s 406-mm shells damaged Turret Bruno and blew <strong>of</strong>f<br />

pieces <strong>of</strong> armor from the turret back plate, killing almost all men in exposed portions on<br />

the bridge. Another 406-mm projectile holed the fore bulkhead <strong>of</strong> the lower bridge.<br />

○ At 0859, a 203-mm shell fired by Norfolk hit and disabled the forward fire-control<br />

director. This certainly resulted in a disruption <strong>of</strong> the fire-control function and the deaths<br />

<strong>of</strong> personnel there, including LCDR Adalbert Schneider, the gunnery <strong>of</strong>ficer.<br />

○ Around 0900, several 406-mm shells struck in the vicinity <strong>of</strong> Turret Bruno. One<br />

<strong>of</strong> these shells hit the upper course <strong>of</strong> 220-mm armor on the port side <strong>of</strong> this turret’s<br />

barbette, creating a significant hole that can be seen on the wreck. <strong>The</strong> turret was trained<br />

to port at the time, engaging Rodney. A chunk <strong>of</strong> 220-mm armor was thrust into the<br />

barbette structure as the shell tore its way through the armor. <strong>The</strong>re was a splinter screen<br />

inside the barbette, which appears designed to absorb the fragments from just such<br />

impacts. However, heavy shells which penetrated the barbette armor more-or-less intact<br />

probably would easily pass through the fragment screen, exploding within the barbette<br />

structure. <strong>The</strong>re is every indication that this is what occurred in this instance. Pieces <strong>of</strong><br />

the shell or debris created a chip about 0.5 meters in length in the upper course <strong>of</strong> 220mm<br />

armor on the far (starboard) side <strong>of</strong> the barbette. Other fragments probably found<br />

their way to the powder magazine, where they caused powder canisters to ignite, along<br />

with some charges within the hoists to the turret above. Since both turrets Anton and<br />

Bruno were in action with Rodney at the time <strong>of</strong> this shell hit, the crew in the gun house<br />

was busy loading shells and powder and canisters into the breeches <strong>of</strong> both guns. Pieces<br />

from that shell’s detonation could have found their way into the turret’s inner spaces and<br />

caused a fire or an explosion to occur there.<br />

○ <strong>The</strong>re is also the possibility that another 406-mm shell penetrated the turret<br />

structure itself at the same time. That situation cannot be confirmed until a thorough<br />

examination <strong>of</strong> Turret Bruno is made from its location on the side <strong>of</strong> the seamount, a<br />

challenging task which may never be possible. It is known that the turret’s back plate was<br />

blown <strong>of</strong>f with pieces <strong>of</strong> that wreckage projected aft, killing all personnel in exposed<br />

positions on the bridge. <strong>The</strong> pressure <strong>of</strong> burning powder and cartridges devastated Turret<br />

Bruno, as the rear <strong>of</strong> the turret was uplifted and thrust forward. That massive pivoting<br />

motion created a divot some one-meter in circumference in the inner forward portion <strong>of</strong><br />

the 220-mm armor plate. <strong>The</strong> turret magazines were flooded shortly thereafter to prevent<br />

a catastrophic explosion. Turret Anton was also silenced around this time. <strong>The</strong> turret’s<br />

guns ran down to maximum depression, probably due to the loss <strong>of</strong> hydraulic power.<br />

○ Sometime during 0900-0915, a 203-mm shell from Norfolk struck the S61 turret<br />

(forward starboard secondary turret) jamming its access hatch. <strong>The</strong> turret crew was<br />

trapped and doomed.<br />

○ About the same time, another 406-mm shell from Rodney hit the forward conning<br />

tower. A series <strong>of</strong> 356-mm and 406-mm hits occurred in rapid sequence, killing many <strong>of</strong><br />

the men inside and chipping or holing the 350-mm armor 25 . <strong>The</strong> port door to the conning<br />

tower is open on the seabed, with some apparent damage to its hinges.<br />

25 Frequently, even non-penetrating hits can cause damage and casualties on the interior due to spalling,<br />

with fragments <strong>of</strong> armor ricocheting around the interior. Another devastating phenomenon is the noise<br />

caused as supersonic projectiles impact on the armor, much like being inside a huge bell as it is rung.<br />

21

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Wreck</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>DKM</strong> <strong>Bismarck</strong> <strong>−</strong> A <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Forensics</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

○ At 0913, a 356-mm shell hit the aft rangefinder over the secondary conning<br />

position and carried away the cupola, optics, and rotating arms. <strong>The</strong> 2001 Expedition<br />

found this cupola with a shell hole (356-mm) clean through.<br />

○ At 0921, a 356-mm shell struck and exploded against the face plate <strong>of</strong> Turret<br />

Caesar. <strong>The</strong>re was no damage within the turret, but its left gun would not elevate. Shell<br />

fragments from the shell’s detonation penetrated the Aufbaudeck and other decks below,<br />

starting small fires that were easily extinguished. <strong>The</strong>se penetrations are still visible in the<br />

deck outside the barbette. <strong>The</strong> Turret Officer, LT Günter Brückner, was forced to halt<br />

firing his guns. He turned to his gun crew and said, “Comrades, we have loved life. Now,<br />

if nothing changes, we will die as good seamen. You may abandon this turret.”<br />

○ Shells struck the forward port side 150-mm secondary turret (P62) and its<br />

magazine, causing internal explosions that tore <strong>of</strong>f the after portion <strong>of</strong> the ro<strong>of</strong> armor<br />

plate (80 mm) and riddled the adjacent superstructure with shell fragments and debris<br />

from the turret.<br />

○ At 0927, gun spotters aboard Norfolk observed a 356-mm shell hit near Turret<br />

Anton. Firing range <strong>of</strong> the shell was estimated to be between 7,300 and 10,000 meters.<br />

○ Sometime during 0930-0935 there was a probable shell hit on the upper main<br />

battery director, which subsequently toppled over to port.<br />

○ Around 0931, the right barrel 26 <strong>of</strong> Turret Dora burst. This probably occurred when<br />

the turret crew fired the gun after it had been damaged by British shellfire. Petty Officer<br />

Friedrich Helms, the gun captain, was able to fire two more rounds from the undamaged<br />

left barrel. <strong>The</strong> hit on the barrel was likely from a 406-mm shell, because soon after the<br />

bursting <strong>of</strong> the right gun, another shell hit the forward port quadrant <strong>of</strong> Turret Dora’s<br />