Curry, Callaloo & Calypso - Macmillan Caribbean

Curry, Callaloo & Calypso - Macmillan Caribbean

Curry, Callaloo & Calypso - Macmillan Caribbean

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

It would be remiss of me not to speak briefly about the cooking methods that were used in<br />

the early days. The slaves would cook for the plantation owners, much of the cooking taking<br />

place in a building away from the great house. In these buildings the slaves usually cooked on an<br />

open fire contained by large stones. The fire was made in the centre and the pots placed upon<br />

the frame of the stones. If baking was done on this fire the pot was placed over the fire, and the<br />

bread dough placed in the pot. The pot was then covered with a sheet of metal and some heat<br />

was placed on top of this metal sheet so as to give heat at both ends. This method was used to<br />

make what we know as ‘pot bake’. Meats were spit-roasted on an open spit. Other baked items<br />

were cooked in a dirt oven, and many areas had a communal oven where anyone could go to<br />

bake their breads and cakes.<br />

By 1797 the English had conquered the islands, also bringing their own slaves, and a<br />

distinctively different type of cooking began to surface. English expertise was shown in the<br />

making of jams and jellies, and beverages like mauby, sorrel and ginger beer.<br />

In 1834 the slaves were emancipated, and from then they refused to work on the plantations.<br />

The skilled cooks amongst them set up shop on street corners, selling dishes they had learned<br />

to cook, such as souse and black pudding, and hence the parlour or shop-front refreshment<br />

stand was born. The land-owners then began to import workers from Barbados, who brought<br />

their own form of recipes such as float and accras and heavy coconut sweet bread. These were<br />

sold under rum shops and in some instances on the street corner. Workers also began to arrive<br />

from China, Portugal and Madeira, all leaving their mark on our culinary map. The largest group<br />

amongst these was the Chinese, whose cooking was changed considerably to suit the palates<br />

of the locals. Their cuisine is very popular as is evident by the number of Trinidad-Chinese<br />

restaurants that exist today.<br />

East Indian immigrants began to arrive between 1845 and 1917, and were registered under<br />

the indenture-ship system to Trinidad. They<br />

brought with them spices like coriander, also<br />

called dhannia, cumin seed (geera), turmeric<br />

or saffron powder, fenugreek, dried legumes<br />

such as channa (chickpeas), rice, and two<br />

sorts of animal: the water buffalo for hard<br />

labour and a type of humped cattle that<br />

provided milk for their beloved yogurt and<br />

butter which was made into ghee. The spices<br />

were ground by hand on what was called<br />

a sill and made into curries, which have<br />

evolved through the years to the distinctively<br />

delicious curry that has become indigenous<br />

to our country.<br />

The East Indians brought not only<br />

ingredients but their own specific methods of<br />

cooking. When they first arrived they began<br />

to cook on a chulla, or mud stove, made with<br />

a combination of river mud, leaves and sticks,<br />

and cow dung. Water was used to smooth<br />

the mud to get a finished look, a process<br />

called leepay. The fire burned from the base<br />

of the chulla. After the chulla came the coal<br />

pot, and then the oil stove followed by the<br />

gasoline stove and, of course, the electric<br />

stove.<br />

16<br />

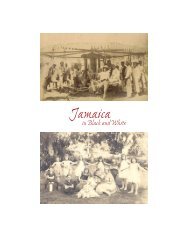

Indentured labourer certificate<br />

9780230038578.indd 16 25/07/2011 13:08