10. Class, Race & Opportunity Hoarding

10. Class, Race & Opportunity Hoarding

10. Class, Race & Opportunity Hoarding

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

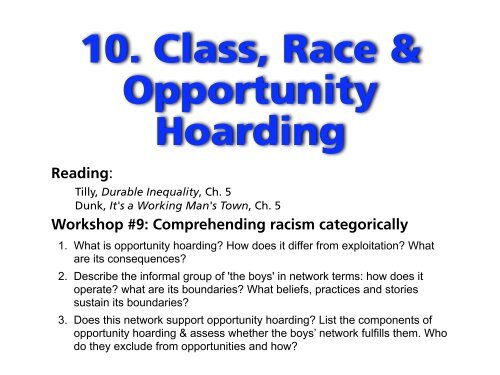

<strong>10.</strong> <strong>Class</strong>, <strong>Race</strong> &<br />

<strong>Opportunity</strong><br />

<strong>Hoarding</strong><br />

Reading:<br />

Tilly, Durable Inequality, Ch. 5<br />

Dunk, It's a Working Man's Town, Ch. 5<br />

Workshop #9: Comprehending racism categorically<br />

1. What is opportunity hoarding? How does it differ from exploitation? What<br />

are its consequences?<br />

2. Describe the informal group of 'the boys' in network terms: how does it<br />

operate? what are its boundaries? What beliefs, practices and stories<br />

sustain its boundaries?<br />

3. Does this network support opportunity hoarding? List the components of<br />

opportunity hoarding & assess whether the boys’ network fulfills them. Who<br />

do they exclude from opportunities and how?

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 10 —<br />

<strong>Opportunity</strong> hoarding<br />

I. <strong>Opportunity</strong> hoarding defined<br />

“When members of a categorically bounded network<br />

acquire access to a resource that is valuable, renewable,<br />

subject to monopoly, supportive of network activities,<br />

& enhanced by the network’s modus operandi, network<br />

members regularly hoard their access to the resource,<br />

creating beliefs & practices that sustain their<br />

control” (Tilly, 91)<br />

II. Relation to exploitation<br />

• a secondary mechanism of durable inequality<br />

• complements exploitation<br />

• done mainly by members of non-elite (i.e. those who are not<br />

exploiters, not powerholders, not owners)<br />

• benefits accrue to members of categorically bounded network<br />

that practices opp. hoarding (conversely, losses to members who<br />

leave the category)<br />

• differences:<br />

• exploitation enlists efforts of others<br />

• opportunity hoarding excludes others<br />

2

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 10 —<br />

Elements of <strong>Opportunity</strong> hoarding<br />

I. categorically bounded network<br />

a. categories<br />

b. boundaries:<br />

i. lumping, splitting & defining<br />

c. network<br />

i. its activities & routines<br />

II. access to a resource<br />

a. valuable<br />

b. renewable<br />

c. subject to monopoly<br />

3

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 10 —<br />

Elements of <strong>Opportunity</strong> hoarding<br />

III. beliefs & practices that sustain their control<br />

a. beliefs<br />

• stories that remind members of affiliation<br />

• negative attributions to other side of boundary<br />

• providing reasons for exclusion<br />

b. practices<br />

• that monitor conduct of members & sanction deviance<br />

• rituals that mark belonging & create emotional bonds<br />

4

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 10 —<br />

Examples of opportunity hoarding<br />

I. Italians in New Jersey vs. Lyon (Tilly, ch. 5)<br />

II. ‘The boys’<br />

III. Professions & occupations<br />

IV. Settler Colonies - nationalism from above<br />

V. Politically mobilized excluded ‘minorities’ -<br />

nationalism from below<br />

5

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 10 —<br />

Analysing opportunity hoarding<br />

II. ‘The boys’ (fill in the information yourself for workshop)<br />

a. categorically bounded network<br />

i. categorical pairs —<br />

•<br />

from whom do the boys try to distinguish themselves?<br />

ii. network: transactions & social relations, and their limits<br />

•<br />

who do they interact with? who don’t they interact with?<br />

iii. boundaries<br />

• how do they mark the boundary between themselves & others?<br />

b. to what extent do they have access to resources that are<br />

i. valuable<br />

ii. renewable<br />

iii. subject to monopoly<br />

iv. supportive of network activities<br />

v. enhanced by the network’s modus operandi<br />

c. what are the beliefs & practices that sustain their control?<br />

i. beliefs: stories, negative attributions, reasons<br />

ii. practices: monitoring, rituals<br />

6

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 10 —<br />

Two approaches to racism<br />

I. Dunk: cultural symbols<br />

a. “The ‘Indian’ is employed as a symbol through which<br />

the Boys establish their own moral worth and their<br />

difference from the perceived dominant power bloc.<br />

They ‘imagine’ their own community in opposition to<br />

others, and racial and ethnic characteristics provide<br />

easily discernible markers upon which such divisions<br />

can be constituted.” (Dunk, 102)<br />

b. “The Indian is perceived as an inferior other against<br />

whom white define themselves. The Indian is also a<br />

powerful symbol in the whites’ understanding of<br />

their relationship to other whites, especially those in<br />

the metropolis located in the southern part of the<br />

province.” (Dunk, 102-3)<br />

7

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 10 —<br />

Two approaches to racism<br />

II. Dunk: ethnic categories<br />

c. ethnic divisions within the European working-class of<br />

Fort William / Port Arthur were important at one<br />

time, with some evidence of concentrations of ethnic<br />

groups in particular industries.<br />

i. “The elevators had been a Scottish preserve in the<br />

early years of their existence” (p. 106).<br />

d. but they became practically insignificant by the<br />

1970s:<br />

i. although stereotypes remain, ethnicity plays no role in<br />

qualifying or disqualifying for membership in the Boys, or in<br />

their choice of female companions; it has little significance for<br />

employment, class or social status (p. 107)<br />

8

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 10 —<br />

Two approaches to racism<br />

III. Dunk: racial categories<br />

e. “… when discussions of Indians arose … Physical<br />

markers, such as relatively dark skin, straight black<br />

hair, high cheekbones and so on become significant<br />

in relation to a cultural, social, and economic<br />

context” (102)<br />

i. ethnic categories: based on perceived cultural differences<br />

ii. racial categories: based on perceived physical differences<br />

f. Where does racial categorization come from?<br />

i. The Boys’ “racism is rooted in the immediate experiences of<br />

their everyday lives and in the prejudices and practices which<br />

are widely present in the culture of the Anglo-Saxon<br />

world” (107)<br />

9

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 10 —<br />

Two approaches to racism<br />

IV. Dunk: from racial categories to racism<br />

g. Negative attribution<br />

i. For the Boys “the Indian stands for negative personality<br />

traits” (107): Indians are lawless (110), don’t respect possessions<br />

(111), are hostile to whites (112), their culture is unsustainable<br />

because the land can no longer support it (112), they have<br />

special privileges (‘we give them too much’ — 113).<br />

h. Boundaries on social relations<br />

i. they avoid places where Indians hang out such as ‘Indian<br />

bars’ (108), and they avoid Indian women (109)<br />

10

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 10 —<br />

Two approaches to racism<br />

V. Dunk: deeper into culture<br />

i. images of Indians in the boys discourse:<br />

• noble savage<br />

• backward simpleton<br />

• victim of outside forces<br />

• degenerate, uncivilized, immoral<br />

• welfare bum<br />

• Indian women: sexually ‘easy’, victims of Indian men (p.<br />

113-115)<br />

j. deep cultural roots<br />

i. images of the other in European ideas of “the wild man and<br />

woman” (122)<br />

ii. alternating images of the noble or the depraved savage (123-4)<br />

11

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 10 —<br />

Two approaches to racism<br />

VI. Dunk: from culture to social relations<br />

a. “The Indian is not only an image against which local<br />

whites define themselves. It is also an important<br />

symbol in their understanding of the hinterland/<br />

metropolis relationship between the region and the<br />

centre of political and economic power in the<br />

South” (115)<br />

b. The Boys feel exploited by the South (118-9), and in<br />

competition with Indians for the benefits of the<br />

welfare state (who pays and who receives) (122).<br />

12

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 10 —<br />

Two approaches to racism<br />

VII. From Dunk to Tilly<br />

‘the Boys’<br />

northern white<br />

working class<br />

‘the South’<br />

political &<br />

economic elite<br />

exploitation opportunity hoarding<br />

opportunity hoarding<br />

boundary<br />

‘Indians’<br />

northern<br />

First Nations<br />

& Métis<br />

13

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 10 —<br />

Two approaches to racism<br />

VIII. Tilly: opportunity hoarding by colonial state<br />

(settler colonialism):<br />

a. excluding natives from land - treaties<br />

b. legal definition of categories<br />

c. definition of ‘Indian’ in Indian Act of 1876<br />

14

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 10 —<br />

Two approaches to racism<br />

IX. Tilly: From opportunity hoarding to exploitation<br />

to opportunity hoarding<br />

a. state’s opportunity hoarding sets stage for<br />

exploitation<br />

i. “powerful, connected people command resources from which<br />

they draw … returns by coordinating the efforts of outsiders<br />

whom they exclude from the full value added by that<br />

effort” (Tilly, 10)<br />

ii. metropolitan - hinterland relation in which resources are<br />

extracted from the hinterland<br />

iii. working-class whites like the Boys benefit from settler colonial<br />

opportunity hoarding, but are exploited, & relatively powerless<br />

compared to the political and economic elite<br />

b. the Boys engage, wittingly or unwittingly, in informal<br />

opportunity hoarding “… a process of informal<br />

exclusion which insures that Natives do not learn of<br />

opportunities in areas such as employment …” (p. 120)<br />

15

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 10 —<br />

Two approaches to racism<br />

X. Tilly: opportunity hoarding in response to<br />

opportunity hoarding<br />

a. treaty rights & aboriginal rights as renewable<br />

resources<br />

b. nationalism ‘from below’: opportunity hoarding to<br />

preserve<br />

i. benefits: welfare benefits, health care, housing, access to jobs,<br />

resource royalties<br />

ii. power to determine their distribution, including who is eligible<br />

to receive them — categorical boundaries<br />

• e.g. Bill C-61<br />

16

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 10 —<br />

Two approaches to racism<br />

XI. Conclusions<br />

a. Two forms of opportunity hoarding?<br />

i. by organizations: “a well-bounded set of ties in which at least<br />

one site has the right to establish ties across the boundary…”<br />

ii. by informal networks: triads + categorical pairs<br />

b. Critique of Dunk, Ch. 5<br />

i. Dunk starts to put the Boys racism in a relational context, but<br />

keeps sliding into its cultural roots instead<br />

c. Tilly’s approach<br />

i. social structure of durable inequality: opportunity hoarding &<br />

exploitation,<br />

ii. culture as a repertoire of stories and beliefs that justify<br />

categorical inequalities of class and ‘race’<br />

17

Soci 220 2009-10 Week 9 —<br />

Next week — December 3<br />

11. <strong>Class</strong>, Knowledge & <strong>Opportunity</strong> <strong>Hoarding</strong><br />

Reading:<br />

Dunk, It's a Working Man's Town, Ch. 6<br />

Workshop #11:<br />

Categorical inequalities, education and occupation<br />

Questions:<br />

1. Why are 'the boys' so anti-intellectual? Why is common sense<br />

highly valued?<br />

2. Can the stories the boys tell about intellectuals and<br />

professionals best be understood in terms of exploitation,<br />

opportunity hoarding or adaptation?<br />

3. Do their stories contribute to creating categorical boundaries<br />

or to solidarity?<br />

18