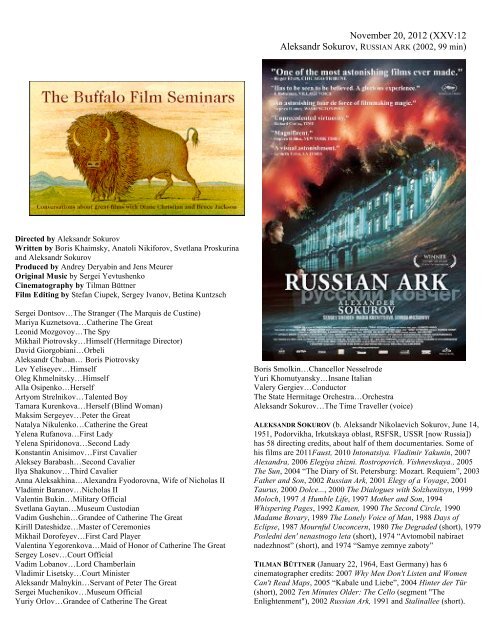

November 20, 2012 (XXV:12 Aleksandr Sokurov, RUSSIAN ARK ...

November 20, 2012 (XXV:12 Aleksandr Sokurov, RUSSIAN ARK ...

November 20, 2012 (XXV:12 Aleksandr Sokurov, RUSSIAN ARK ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Directed by <strong>Aleksandr</strong> <strong>Sokurov</strong><br />

Written by Boris Khaimsky, Anatoli Nikiforov, Svetlana Proskurina<br />

and <strong>Aleksandr</strong> <strong>Sokurov</strong><br />

Produced by Andrey Deryabin and Jens Meurer<br />

Original Music by Sergei Yevtushenko<br />

Cinematography by Tilman Büttner<br />

Film Editing by Stefan Ciupek, Sergey Ivanov, Betina Kuntzsch<br />

Sergei Dontsov…The Stranger (The Marquis de Custine)<br />

Mariya Kuznetsova…Catherine The Great<br />

Leonid Mozgovoy…The Spy<br />

Mikhail Piotrovsky…Himself (Hermitage Director)<br />

David Giorgobiani…Orbeli<br />

<strong>Aleksandr</strong> Chaban… Boris Piotrovsky<br />

Lev Yeliseyev…Himself<br />

Oleg Khmelnitsky…Himself<br />

Alla Osipenko…Herself<br />

Artyom Strelnikov…Talented Boy<br />

Tamara Kurenkova…Herself (Blind Woman)<br />

Maksim Sergeyev…Peter the Great<br />

Natalya Nikulenko…Catherine the Great<br />

Yelena Rufanova…First Lady<br />

Yelena Spiridonova…Second Lady<br />

Konstantin Anisimov…First Cavalier<br />

Aleksey Barabash…Second Cavalier<br />

Ilya Shakunov…Third Cavalier<br />

Anna Aleksakhina…Alexandra Fyodorovna, Wife of Nicholas II<br />

Vladimir Baranov…Nicholas II<br />

Valentin Bukin…Military Official<br />

Svetlana Gaytan…Museum Custodian<br />

Vadim Gushchin…Grandee of Catherine The Great<br />

Kirill Dateshidze…Master of Ceremonies<br />

Mikhail Dorofeyev…First Card Player<br />

Valentina Yegorenkova…Maid of Honor of Catherine The Great<br />

Sergey Losev…Court Official<br />

Vadim Lobanov…Lord Chamberlain<br />

Vladimir Lisetsky…Court Minister<br />

<strong>Aleksandr</strong> Malnykin…Servant of Peter The Great<br />

Sergei Muchenikov…Museum Official<br />

Yuriy Orlov…Grandee of Catherine The Great<br />

<strong>November</strong> <strong>20</strong>, <strong>20</strong><strong>12</strong> (<strong>XXV</strong>:<strong>12</strong><br />

<strong>Aleksandr</strong> <strong>Sokurov</strong>, <strong>RUSSIAN</strong> <strong>ARK</strong> (<strong>20</strong>02, 99 min)<br />

Boris Smolkin…Chancellor Nesselrode<br />

Yuri Khomutyansky…Insane Italian<br />

Valery Gergiev…Conductor<br />

The State Hermitage Orchestra…Orchestra<br />

<strong>Aleksandr</strong> <strong>Sokurov</strong>…The Time Traveller (voice)<br />

ALEKSANDR SOKUROV (b. <strong>Aleksandr</strong> Nikolaevich <strong>Sokurov</strong>, June 14,<br />

1951, Podorvikha, Irkutskaya oblast, RSFSR, USSR [now Russia])<br />

has 58 directing credits, about half of them documentaries. Some of<br />

his films are <strong>20</strong>11Faust, <strong>20</strong>10 Intonatsiya. Vladimir Yakunin, <strong>20</strong>07<br />

Alexandra, <strong>20</strong>06 Elegiya zhizni. Rostropovich. Vishnevskaya., <strong>20</strong>05<br />

The Sun, <strong>20</strong>04 “The Diary of St. Petersburg: Mozart. Requiem”, <strong>20</strong>03<br />

Father and Son, <strong>20</strong>02 Russian Ark, <strong>20</strong>01 Elegy of a Voyage, <strong>20</strong>01<br />

Taurus, <strong>20</strong>00 Dolce..., <strong>20</strong>00 The Dialogues with Solzhenitsyn, 1999<br />

Moloch, 1997 A Humble Life, 1997 Mother and Son, 1994<br />

Whispering Pages, 1992 Kamen, 1990 The Second Circle, 1990<br />

Madame Bovary, 1989 The Lonely Voice of Man, 1988 Days of<br />

Eclipse, 1987 Mournful Unconcern, 1980 The Degraded (short), 1979<br />

Posledni den' nenastnogo leta (short), 1974 “Avtomobil nabiraet<br />

nadezhnost” (short), and 1974 “Samye zemnye zaboty”<br />

TILMAN BÜTTNER (January 22, 1964, East Germany) has 6<br />

cinematographer credits: <strong>20</strong>07 Why Men Don't Listen and Women<br />

Can't Read Maps, <strong>20</strong>05 “Kabale und Liebe”, <strong>20</strong>04 Hinter der Tür<br />

(short), <strong>20</strong>02 Ten Minutes Older: The Cello (segment "The<br />

Enlightenment"), <strong>20</strong>02 Russian Ark, 1991 and Stalinallee (short).

SERGEI YEVTUSHENKO has four composer credits: <strong>20</strong>09 The Last<br />

Station, <strong>20</strong>07 The Border, <strong>20</strong>02 Russian Ark, and 1999 Robert. A<br />

Fortunate Life (short).<br />

SERGEI DONTSOV… The Stranger (The Marquis de Custine) (b.<br />

Sergei Simonovich Drejden, September 14, 1941) has 24 acting<br />

credits: <strong>20</strong>11 Expiation, <strong>20</strong>09 “Ivan Groznyy”, <strong>20</strong>09 Taras Bulba,<br />

<strong>20</strong>09 Help Gone Mad, <strong>20</strong>08 Antonina obernulas, <strong>20</strong>07 Jolka, <strong>20</strong>06<br />

Mnogotochie, <strong>20</strong>04 Daddy, <strong>20</strong>03 Do Not Make Biscuits in a Bad<br />

Mood, <strong>20</strong>02 Russian Ark, <strong>20</strong>02 The Tale of Fedot, the Shooter, <strong>20</strong>01<br />

Podari mne lunnyy svet, 1999 Marigolds in Flower, 1998 Tsirk<br />

sgorel, i klouny razbezhalis, 1994 Viva Castro!, 1994 Okno v Parizh,<br />

1993 Drug voyny (short), 1993 Vladimir svyatoy, 1991 Abdulladzhan,<br />

ili posvyashchaetsya Stivenu Spilbergu, 1990 Tank 'Klim Voroshilov-<br />

2', 1989 Fontan, 1975 Moy dom, teatr, 1975 Vozdukhoplavatel, and<br />

1966 A Ballad of Love.<br />

MARIYA KUZNETSOVA…Catherine The Great has 17 acting<br />

credits: <strong>20</strong>09 Dvoynaya propazha, <strong>20</strong>06 Vy ne ostavite menya, <strong>20</strong>06<br />

Travesti, <strong>20</strong>05 Dreaming of<br />

Space, <strong>20</strong>05 The Italian, <strong>20</strong>05<br />

Golova Klassika, <strong>20</strong>05 “Kazus<br />

Kukotskogo”, <strong>20</strong>04 Imeniny,<br />

<strong>20</strong>03 Tayna Zaborskogo omuta,<br />

<strong>20</strong>02 Tycoon: A New Russian,<br />

<strong>20</strong>02 Russian Ark, <strong>20</strong>02 “Lyubov<br />

imperatora”, <strong>20</strong>01 Taurus, 1994<br />

Koleso lyubvi, 1992 Glaza, 1989<br />

Utoli moya pechali, and 1987<br />

“Gde by ni rabotat....”<br />

LEONID MOZGOVOY…The Spy<br />

has 13 acting credits:<br />

<strong>20</strong>11 “Raspoutine”, <strong>20</strong>11 Gogol.<br />

Blizhayshiy, <strong>20</strong>09 “Isayev”, <strong>20</strong>09<br />

“Ivan Groznyy”, <strong>20</strong>07<br />

Dyuymovochka, <strong>20</strong>07 The<br />

Border, <strong>20</strong>06 Gadkie lebedi, <strong>20</strong>05 Garpastum, <strong>20</strong>02 Russian Ark,<br />

<strong>20</strong>01 Taurus, <strong>20</strong>01 Text or Apologia of a Commentary, 1999 Moloch,<br />

1992 Kamen, <strong>20</strong>04 Bozhestvennaya Glikeriya, and <strong>20</strong>03 In One<br />

Breath: Alexander <strong>Sokurov</strong>'s Russian Ark (short).<br />

MIKHAIL PIOTROVSKY…Himself (Hermitage Director) has four<br />

acting credits, all as himself: <strong>20</strong>11 “Pozner”, <strong>20</strong>03 “Shkola<br />

zlosloviya”, <strong>20</strong>03 In One Breath: Alexander <strong>Sokurov</strong>'s Russian Ark<br />

(short), and <strong>20</strong>02 Russian Ark.<br />

ALEKSANDR CHABAN…Boris Piotrovsky has four acting credits:<br />

<strong>20</strong>05 “The Master and Margarita” (9 episodes), <strong>20</strong>02 Russian Ark,<br />

<strong>20</strong>02 “Lyubov imperatora”, and 1992 The Waiting Room.<br />

ALLA OSIPENKO… Herself (1932, Leningrad, USSR [now St.<br />

Petersburg, Russia]) has 8 acting credits: <strong>20</strong>02 Russian Ark, 1989<br />

Otche nash, 1988 Filial, 1987 Fuete, 1987 Mournful Unconcern,<br />

1987 Ampir (short), 1985 Zimnyaya vishnya, and 1982 Golos .<br />

D.<br />

From Wikipedia:<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong>—<strong>RUSSIAN</strong> <strong>ARK</strong>—2<br />

Alexander Nikolayevich <strong>Sokurov</strong> (Russian: Алекса́ндр<br />

Никола́евич Соку́ров; born June 14, 1951) is a Russian filmmaker.<br />

His most significant works include a feature film, Russian Ark<br />

(<strong>20</strong>02), filmed in a single unedited shot, and Faust (<strong>20</strong>11), which was<br />

honoured with the Golden Lion, the highest prize for the best film at<br />

the Venice Film Festival.<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong> was born in Podorvikha, Irkutsk Oblast, in Siberia,<br />

into a military officer's family. He graduated from the History<br />

Department of the Nizhny Novgorod University in 1974 and entered<br />

one of the VGIK studios the following year. There he became friends<br />

with Tarkovsky and was deeply influenced by his film Mirror. Most<br />

of <strong>Sokurov</strong>'s early features were banned by Soviet authorities. During<br />

his early period, he produced numerous documentaries, including an<br />

interview with <strong>Aleksandr</strong> Solzhenitsyn and a reportage about Grigori<br />

Kozintsev's flat in St Petersburg. His film Mournful Unconcern was<br />

nominated for the Golden Bear at the 37th Berlin International Film<br />

Festival in 1987.<br />

Mother and Son (1997) was his first internationallyacclaimed<br />

feature film. It was mirrored by Father and Son (<strong>20</strong>03),<br />

which baffled the critics with its<br />

implicit homoeroticism (though<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong> himself has criticized this<br />

particular interpretation). Susan<br />

Sontag included two <strong>Sokurov</strong><br />

features among her ten favorite<br />

films of the 1990s, saying:<br />

"There’s no director active today<br />

whose films I admire as much." In<br />

<strong>20</strong>06, he received the Master of<br />

Cinema Award of the International<br />

Filmfestival Mannheim-<br />

Heidelberg.<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong> is a Cannes Film<br />

Festival regular, with four of his<br />

movies having debuted there.<br />

However, until <strong>20</strong>11, <strong>Sokurov</strong><br />

didn't win top awards at major<br />

international festivals. For a long time, his most commercially and<br />

critically successful film was the semi-documentary Russian Ark<br />

(<strong>20</strong>02), acclaimed primarily for its visually hypnotic images and<br />

single unedited shot.<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong> has filmed a tetralogy exploring the corrupting<br />

effects of power. The first three installments were dedicated to<br />

prominent <strong>20</strong>th-century rulers: Moloch (1999), about Hitler, Taurus<br />

(<strong>20</strong>00), about Lenin, and The Sun (<strong>20</strong>04) about Emperor Hirohito. In<br />

<strong>20</strong>11, <strong>Sokurov</strong> shot the last part of the series, Faust, a retelling of<br />

Goethe's tragedy. The film, depicting instincts and schemes of Faust<br />

in his lust for power, premiered on 8 September <strong>20</strong>11 in competition<br />

at the 68th Venice International Film Festival. The film won the<br />

Golden Lion, the highest award of the Venice Festival. Producer<br />

Andrey Sigle said about Faust: "The film has no particular relevance<br />

to contemporary events in the world—it is set in the early 19th<br />

century—but reflects <strong>Sokurov</strong>'s enduring attempts to understand man<br />

and his inner forces."<br />

The military world of the former USSR is one of <strong>Sokurov</strong>’s<br />

ongoing interests, because of his personal connections to the subject<br />

and because the military marked the lives of a large part of population<br />

of the USSR. Three of his works, Spiritual Voices: From the Diaries<br />

of a War, Confession, From the Commander’s Diary and Soldier’s

Dream revolve around military life. "Confession" has been screened<br />

at several independent film festivals, while the other two are virtually<br />

unknown.<br />

In 1994 <strong>Sokurov</strong> accompanied Russian troops to a post on<br />

the Tajikistan-Afghanistan border. The result was Spiritual Voices:<br />

From the Diaries of a War, a 327-minute cinematic meditation on the<br />

war and the spirit of the Russian army. Landscape photography is<br />

featured in the film, but the music (including works by Mozart,<br />

Messiaen and Beethoven) and the sound are also particularly<br />

important. Soldiers’ jargon and the combination of animal sounds,<br />

sighs and other location sounds in the fog and other visual effects<br />

give the film a phantasmagorical feel. The film brings together all the<br />

elements that characterize <strong>Sokurov</strong>’s films: long takes, elaborate<br />

filming and image processing methods, a mix of documentary and<br />

fiction, the importance of the landscape and the sense of a filmmaker<br />

who brings transcendence to everyday gestures.<br />

On the journey from Russia to the border post, in the film,<br />

fear never leaves the faces of the young soldiers. <strong>Sokurov</strong> captures<br />

their physical toil and their mental desolation, as well as daily rituals<br />

such as meals, sharing tobacco, writing letters and cleaning duties.<br />

There is no start or end to the dialogues; <strong>Sokurov</strong> negates<br />

conventional narrative structure. The final part of the film celebrates<br />

the arrival of the New Year, 1995, but the happiness is fleeting. The<br />

following day, everything remains the same: the endless waiting at a<br />

border post, the fear and the desolation.<br />

In Confession: From the Commander’s Diary, <strong>Sokurov</strong><br />

films officers from the Russian Navy, showing the monotony and<br />

lack of freedom of their everyday lives. The dialogue allows us to<br />

follow the reflections of a Ship Commander. <strong>Sokurov</strong> and his crew<br />

went aboard a naval patrol ship headed for Kuvshinka, a naval base in<br />

the Murmansk region, in the Barents Sea. Confined within the limited<br />

space of a ship anchored in Arctic waters, the team filmed the sailors<br />

as they went about their routine activities.<br />

Soldier’s Dream is another <strong>Sokurov</strong> film that deals with<br />

military themes. It contains no dialogue. This film actually came out<br />

of the material edited for one of the scenes in part three of Spiritual<br />

Voices. Soldier’s Dream was screened at the Oberhausen Film<br />

Festival in Germany in 1995 – when Spiritual Voices was still at the<br />

editing stage – as <strong>Sokurov</strong>'s homage to the art critic and historian<br />

Hans Schlegel, in acknowledgement of his contributions in support of<br />

Eastern European filmmakers.<br />

Pasquale Iannone in Senses of Cinema:<br />

Following on from Goethe’s famous observation that “architecture is<br />

frozen music”, Raymond Durgnat has argued that cinema is<br />

“unfrozen architecture”: “When the camera moves, the roofline flows<br />

past us like a river. The camera tilts rapidly up, and banister and<br />

staircase cascade down.”<br />

However, the camera, Durgnat argues, “explodes<br />

architecture” because of its ability to distort scale. The latter emphasis<br />

on the camera almost as mutilator could not be further from the<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong>—<strong>RUSSIAN</strong> <strong>ARK</strong>—3<br />

reverence, the child-like wonder with which Alexandr <strong>Sokurov</strong><br />

approaches the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, the setting of his<br />

monumental film Russian Ark/Russkiy kovcheg.<br />

The film’s sheer scale and ambition elicited gasps of awe<br />

upon its release in <strong>20</strong>02. Four years in development, it was the first<br />

feature to be shot in one continuous, HD Steadicam shot covering<br />

more than one and a half kilometres. Utilising more than 850<br />

professional actors, 1000 extras and spanning three centuries of<br />

Russian history, the film is set in a museum which holds several<br />

million artworks. Russian Ark was, as <strong>Sokurov</strong> has stated, an attempt<br />

to make a film “in one breath”.<br />

The film’s narrative drive comes from the relationship<br />

between the off-screen Russian narrator (<strong>Sokurov</strong> himself) and the<br />

on-screen Marquis Astolphe de Custine (Sergei Dreiden), a 19 th<br />

century French diplomat. Custine, in his inflexible conviction of the<br />

supremacy of Western European art over that of Russia, is the oftencynical<br />

guide to the 33 opulent salons of the Hermitage (which,<br />

before 1917, was of course the Winter Palace). As the camera moves<br />

through the museum, the director recreates critical moments in<br />

Russian history, introducing historical figures such as Catherine the<br />

Great, Peter I (the founder of St Petersburg in 1703) and Tsar<br />

Nicholas II.<br />

Charlotte Garson has rightly observed that the film, as an<br />

extended plan-séquence, has its aesthetic antecedents in such films as<br />

those of Miklos Jancsò, Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948) and the<br />

cinema of Max Ophuls. Garson tantalisingly speculates on how, with<br />

access to <strong>Sokurov</strong>’s technology, these directors would have<br />

undoubtedly relished the opportunity of composing an entire feature<br />

in a single extended sweep of the camera. However, for Sukurov, the<br />

technique is no gimmick, no “vain formal feat” or “supplementary<br />

aesthetic trump card” – it is the very essence of the film. It could be<br />

argued that the key relationship of Russian Ark is not that between the<br />

narrator and the Marquis but that between the camera and the<br />

Hermitage. The film’s mise en scène is the living culture of Russian<br />

and European history.<br />

Of the directors cited above, I would argue that camera<br />

movement in <strong>Sokurov</strong>’s film comes closest to the feathery, ethereal<br />

glide of Ophuls, indeed many references are made in <strong>Sokurov</strong>’s film<br />

to floating, birds and flying. One passage near the beginning of the<br />

film, moving left to right outside a succession of windows recalls the<br />

opening sequence of “Le Maison Tellier”, the central story in Le<br />

Plaisir (1952), Ophuls’ adaptation of three stories by Guy de<br />

Maupassant. Decidedly Ophulsian too, is <strong>Sokurov</strong>’s frequent<br />

subjugation of camera movement to actors. In the densely populated<br />

ceremonial scenes or the climactic ball, the movement of Tilman<br />

Büttner’s steadicam, whether moving along tightly regimented<br />

columns of soldiers or weaving amongst dancers, is never intrusive –<br />

characters swirl around the camera unencumbered. However, whilst<br />

Ophuls’ camera at times takes flight (and, as Kubrick famously<br />

exclaimed, “moves through walls”), <strong>Sokurov</strong>’s gaze can be more<br />

closely likened to that of a child – free certainly, insatiably curious,<br />

but also cautious, often coming close to being a Deleuzian seer. On<br />

the opening of each salon door, the camera hovers in wide-eyed<br />

anticipation. Each opening is a revelation and none more so than the<br />

door opening into “1917” and leading to the introduction of Anastasia<br />

and her sisters, one of the film’s most joyous, exhilarating passages.<br />

The Marquis shoos, then playfully runs after the children. Passing an<br />

exhausted Custine, the camera too careers breathlessly after them. As<br />

a snapshot of the twilight of the Romanov dynasty, it is

unmistakeably Viscontian in its elegiac quality.<br />

The relationship between Custine and the narrator is one<br />

whose dynamic shifts as regularly as the film’s diegesis shifts in<br />

space and time. The Marquis is first presented almost as a Nosferatulike<br />

figure emerging from the shadows. Wiry, pallid, hunched and<br />

clad in black with sprigs of grey hair he becomes an irascible, laconic<br />

guide to the treasures of the Hermitage. His teacherly status is<br />

abruptly reversed when he arrives at a cold, colourless salon, filled<br />

with dust and empty frames – we are now in the time of World War<br />

II. A bewildered Marquis is warned by the narrator not to enter but he<br />

does so nonetheless, encountering a museum worker in a room<br />

depicting the hardship imposed on the Russian people and its culture<br />

during the siege of Leningrad.<br />

Tim Harte has observed that Custine “has gotten a stark<br />

glimpse of the mortality<br />

that contrasts with the<br />

film’s earlier evocations<br />

of the eternal within the<br />

ubiquitous ‘living’<br />

frames featured<br />

elsewhere in the<br />

museum.” It is the<br />

narrator now who has to<br />

provide a history lesson<br />

for the Marquis. Apart<br />

from this wartime<br />

segment, it is interesting<br />

to note that there almost<br />

nothing in the film on<br />

the Soviet era, with no<br />

mention of figures such<br />

as Lenin or Stalin.<br />

Somewhat<br />

predictably for a film<br />

whose visuals are so<br />

spectacular, the film’s sound design has been largely neglected in<br />

critical writings. There can surely be little doubt that the meticulous<br />

visual choreography is also matched by the aural. After the opening<br />

titles, and before a fade-in allows the camera to begin its flight,<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong> introduces his narrator in complete darkness, with gusts of<br />

wind whistling on the soundtrack. The director’s own delivery is akin<br />

to that of one who has awoken from deep sleep in a state of<br />

bewilderment: “Where am I? Where are they rushing to? Has this all<br />

been staged for me? Am I expected to play a role?” If we return to the<br />

motif of the child, this emergence from darkness is of course akin to<br />

birth.<br />

As the camera progresses through the Hermitage, the<br />

soundtrack is peppered by whispers, chatter and hushed laughter from<br />

a plethora of characters. But constant throughout the film is an<br />

audible breathing – presumably of the narrator – symbolic of a culture<br />

that is living, a culture “destined to sail forever”.<br />

Harry Sheehan in LA Weekly, Jan 10-16, <strong>20</strong>03, “Russian Ark”:<br />

Writer-director Alexander (née <strong>Aleksandr</strong>) <strong>Sokurov</strong> — a perennial<br />

presence at major film festivals with such recent work as Taurus<br />

(<strong>20</strong>00), Moloch (1999) and, earlier and much more satisfactorily,<br />

Mother and Son (1996) — is on the whole more respected than<br />

beloved. Before attending film school, the now-51-year-old country<br />

boy – turned – St. Petersburger got his university degree in history,<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong>—<strong>RUSSIAN</strong> <strong>ARK</strong>—4<br />

and has looked there for his subject matter ever since. Only it's not<br />

just history, to hear his admirers tell it: On <strong>Sokurov</strong>'s own official<br />

Web site, one Russian critic describes the filmmaker's subject as<br />

"man and his fate" — surely a daunting ambition for anyone's<br />

lifework, and one that has led to accusations of grandiosity.<br />

Certainly, only an artist with an inflated sense of mission could<br />

conceive of his work as a kind of biblical ark for 300 years of modern<br />

Russian history. Russian Ark opens with a black screen and the voice<br />

of an unnamed filmmaker (<strong>Sokurov</strong>'s, actually) explaining that he's<br />

just regaining consciousness after some mysterious "accident" —<br />

perhaps, the viewer may come to believe, the historical "anomaly" of<br />

Russian communism. When the black gives way to a clear image,<br />

we're in a back courtyard of the Hermitage museum complex (of<br />

which Peter the Great's Winter Palace is the oldest building) amid<br />

officers and ladies,<br />

dressed in 18thcentury<br />

finery, as they<br />

make their way to a<br />

party inside. The<br />

camera/unseen<br />

filmmaker scurries<br />

along with them and<br />

soon meets up with<br />

the figure who will be<br />

our companion and<br />

guide, a 19th-century<br />

French diplomat<br />

known only as the<br />

Marquis (Sergey<br />

Dreiden) — a man of<br />

exquisite taste, and at<br />

the same time a<br />

familiar Russian<br />

punching bag, the<br />

Western dilettante<br />

blind to the depths of the aggrieved Russian soul.<br />

With the Marquis' appearance, the film settles into its formal<br />

structure, a journey through the Hermitage as art museum and living<br />

historical presence. Working with German cinematographer Tilman<br />

Büttner, who was the Steadicam operator on Tom Tykwer's Run Lola<br />

Run, <strong>Sokurov</strong> shot all of Russian Ark as one continuous take. To<br />

accomplish this, he employed a high-definition video camera that<br />

stored its images on a specially developed portable hard drive that<br />

could record up to 100 minutes of uncompressed images. (The video<br />

image was eventually transferred to 35mm film.) As the camera<br />

makes its way through the Hermitage museum in St. Petersburg, the<br />

"ark" of the title, it weaves in and out of time periods, assessing<br />

canvases and sculptures, glimpsing small vignettes and vast scenes.<br />

To make sure that our eyes don't get bored, the camera moves up,<br />

down and all around, compensating for the absence of editing by<br />

continually reframing the action.<br />

But clearly, something more serious than stylistic innovation is<br />

afoot here — something too serious, <strong>Sokurov</strong> must have felt, for mere<br />

drama. Russian Ark doesn't act so much as it muses: on art, on<br />

history, on Russia versus the West, on politics. The first long segment<br />

of the tour touches upon the creation of the Winter Palace by Peter<br />

the Great (Maxim Sergeyev), whom we spy in a small room, dressed<br />

in one of his favored peasant costumes, thrashing a general<br />

presumptuous enough to have made advances to a princess. This

Asiatic tyrant, the Marquis sniffs, is a cultural parvenu who, tellingly,<br />

built his "European" edifice on a swamp.<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong>'s rejoinder is purely cinematic, a stunning coup of motion<br />

that brings us up and down twisting<br />

staircases, out into a vineyard of ropes and<br />

creaking pulleys, a working backstage,<br />

down across the top of an orchestra pit, and<br />

up to a balcony where Catherine the Great<br />

(who founded the Hermitage as a museum<br />

and stocked it with paintings and sculpture)<br />

directs her own play, then dashes out to an<br />

upstairs foyer in desperate need of a place<br />

in which to "piss." High art, low comedy,<br />

hard labor and royal prerogative are here<br />

thrown together in an elegant unity, a<br />

breathtaking demonstration of Russian<br />

cinematic — hence artistic — brilliance.<br />

Russian Ark now begins a new sequence, detouring into a gallery<br />

filled with modern-day museum visitors. Without finding the Marquis<br />

particularly out of place, two of them — a doctor and an actor, friends<br />

of <strong>Sokurov</strong> — draw him over to a Tintoretto painting (The Birth of<br />

John the Baptist) and discuss the symbolism of a cat and a chicken.<br />

Next, the Marquis encounters a blind woman feeling a statue; she<br />

takes him onward to her favorite painting and stands aside as he<br />

smells the oil on the canvas.<br />

An intense desire to reanimate the artworks by bringing all the<br />

senses to bear on them culminates in a gallery of Goyas. Both the<br />

Roman Catholic Marquis and the ever-unseen <strong>Sokurov</strong> are struck<br />

dumb by the religiously themed canvases, as the camera nearly<br />

brushes up against them in a gesture of infatuation. By now, the film's<br />

allusiveness has grown extraordinarily intense: Goya's rejection of<br />

perspective and line in favor of color and light reflects the differences<br />

between film and video. And in the very next scene, the Marquis<br />

attacks a young Russian boy for not knowing enough to admire a<br />

portrait of saints Peter and Paul he's gazing at, undoubtedly a<br />

reference to the palace's Tower of Saints Peter and Paul, a site of<br />

much historical strife.<br />

Up till now, Russian Ark has been technically fascinating, but<br />

essentially cold and didactic. Now, energized by his encounter with<br />

fine art, the Marquis starts rhapsodizing over the cultural<br />

sophistication of the Russian czars. Oh, they were beasts, he says, but<br />

what good taste! (He would naturally think so: The Romanov court<br />

famously aped the French court in fashion and etiquette.) Then, in a<br />

fit of idle curiosity, he opens a door, only to find a hulk of a<br />

workingman — a survivor of Germany's 900-day siege of Leningrad<br />

(Soviet-speak for St. Petersburg), in which as many as a million<br />

Russians succumbed to hunger and disease — talking of death and<br />

destruction. But the Marquis doesn't want to hear about it. He slams<br />

the door shut and runs off to another building to join in a series of<br />

masques, official ceremonies and, finally, a gigantic, brilliantly<br />

photographed ball that, according to the press notes, depicts the last<br />

Great Royal Ball ever held in the Winter Palace, in 1913. Transfixed<br />

by the high life of the royal court, the Marquis doesn't want to hear<br />

about the struggles of the Russian masses.<br />

But what, in the end, does <strong>Sokurov</strong> want to tell us about them?<br />

Between the big fancy-dress scenes, there are smaller, more nostalgic<br />

moments. After a small group of lovely girls skip down a hall dressed<br />

as angels, one goes in to sit with her father, Emperor Nicholas II, and<br />

mother, Empress Alexandra, and is addressed as Anastasia. <strong>Sokurov</strong><br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong>—<strong>RUSSIAN</strong> <strong>ARK</strong>—5<br />

is invoking one of the great myths of White Russia, that of the<br />

missing princess who escaped the Bolshevik firing squad. Russian<br />

Ark is dallying with reaction here, and the flirtation persists right up<br />

to the film's end, which coincides with the end<br />

of the ball. As many hundreds of noble and<br />

military guests make their way down<br />

decorous, baroque-neoclassical halls to the<br />

huge main staircase, the camera walks among<br />

this politely surging mass of polished<br />

humanity and, in a last bravura flourish, turns<br />

and faces them head-on at the door and<br />

watches as they pass behind and into the street.<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong> displays enormous ambivalence<br />

throughout these scenes of court life. While<br />

the Marquis runs off to join in the ball — and,<br />

indeed, on many occasions when the Marquis<br />

runs off — the director's voice warns him to hold back. During the<br />

ball, the Marquis, as he waltzes, can't even hear the director's voice as<br />

he mourns the passing of so many lives, though not the end of this<br />

way of life. As he stands and watches the partygoers exit to their<br />

doom, it's with a certain detachment.<br />

The film has a secret code, and the code book is V.I. Pudovkin's<br />

1927 Bolshevik classic The End of St. Petersburg, a story of the<br />

communist revolution. As dedicated to expressive editing as <strong>Sokurov</strong><br />

is to long, long takes, Pudovkin ended his film on the same grand<br />

staircase as does <strong>Sokurov</strong>. But Pudovkin used montage to ascend the<br />

stairs and focused on an individual, a revolutionary woman searching<br />

for her husband.<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong>’s long, unbroken shot with a huge group of aristocrats is<br />

a riposte to Pudovkin’s. Additionally, <strong>Sokurov</strong>’s movie ends the same<br />

year Pudovkin’s begins. Is <strong>Sokurov</strong> voicing a preference for the<br />

refinement of individual taste drawn from masses of undifferentiated<br />

aristocrats over the masses as represented by a single individual. It’s<br />

difficult to say. Both films, in a sense, are overcome by their<br />

techniques.<br />

But <strong>Sokurov</strong> does connect one piece of history with another and<br />

that is no small accomplishment.<br />

Jeremy Heilman on MovieMartyr.com:<br />

Surely one of the most technically impressive cinematic stunts ever<br />

attempted, I suppose one could say that Russian Ark, <strong>Aleksandr</strong><br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong>’s ambitious new film centers around a gimmick, but you<br />

realize it’s one hell of a gimmick once you see it implemented.<br />

Filmed entirely in one shot, this digital experiment is insanely<br />

elaborate in its compositions and costuming. It makes even the<br />

complex multiple split screen techniques of Mike Figgis’ Time Code<br />

look simplistic. What begins as an exploration of the halls of the<br />

Royal Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg soon becomes a tour of<br />

modern Russia’s, and human, history. Instead of the series of<br />

relatively static tableaux that I expected, though, Sokoruv ducks,<br />

bobs, and weaves his way throughout the museum with as much<br />

aplomb as any director working without a one-shot quota. The<br />

script’s surprising playfulness keeps things fresh as the movie buzzes<br />

along. History becomes a malleable and transient thing as with entry<br />

into each decked out room we enter into another era of time and<br />

history. When we encounter an elderly Catherine II after earlier<br />

seeing a younger version of her frolicking about in the same shot<br />

some minutes earlier, it comments mournfully on the rapidity with<br />

which we age.

All of the sumptuous period detail that <strong>Sokurov</strong> piles on during<br />

Russian Ark is given the expected reverence of a film that's been<br />

made with the blessing of a state museum, but the film never becomes<br />

didactic or boring because of the larger theme that binds together all<br />

of the temporal and spatial places that we travel during the course of<br />

the shot. With his typically sparse philosophical aloofness, the<br />

director puts forth the intriguing idea that we honor history and save<br />

art so that we might fend off our own undeniable mortality. In<br />

scattered moments throughout the journey, this premise achieves real<br />

emotional poignancy. The gracefully floating camera conveys the<br />

mostly unseen narrator’s point of view, but he occasionally interacts<br />

with a mysterious European man in black, who is a lot more vocal<br />

about his sense of loss. Through their relationship, which echoes the<br />

rapport between Russia and the rest of Europe, we come to<br />

understand the way that Russia became a country that became so<br />

utterly convinced of the power of its own pageantry. Other scenes,<br />

such as the indelible one where we see a blind woman caressing the<br />

works of a master sculptor so she might understand their greatness,<br />

are no less affecting. It becomes quite apparent that the bond between<br />

the transcendent nature of great art and the inevitability of human<br />

foible is an unbreakable and necessary link, and <strong>Sokurov</strong>’s<br />

examination of the two is as thought provoking as it’s nimbly<br />

presented. For those who find <strong>Sokurov</strong>’s philosophies tiresome,<br />

Russian Ark is still a must-see. Even before it builds up to its insanely<br />

staged ballroom scene, in which 3000 actors appear in full regalia, it’s<br />

waltzed itself into the art film pantheon.<br />

Birgit Beumers, KinoKultura <strong>20</strong>03:<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong>’s Russian Ark (Russkii kovcheg, <strong>20</strong>02) is a 96-minute-long<br />

tracking shot filmed with a steadicam held by the director of<br />

photography Tilman Buettner, whose excellent camerawork could be<br />

seen in Run Lola Run (Lola rennt, Tom Tykwer, 1997). There is thus<br />

not a single cut in this film. The camera follows minutely<br />

choreographed movements along a 1.5 km track with 33 sets of the<br />

862 actors donning 360 costumes and masked with three buckets of<br />

powder. The filming took place on 23 December <strong>20</strong>01, the shortest<br />

day in the year, in the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, leaving<br />

just four hours of daylight during the polar nights for filming after<br />

two days of preparation in the museum. The film creates the<br />

impression that the uninterrupted journey through 300 years of<br />

history and 33 rooms of the Hermitage takes just one long breath. The<br />

sensation of floating through history is achieved by a sheer technical<br />

feat.<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong> compresses time. On the one hand, there are scenes<br />

from the life of the Russian tsars in chronological order: Peter the<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong>—<strong>RUSSIAN</strong> <strong>ARK</strong>—6<br />

Great beats his general; Catherine the Great attends a rehearsal in the<br />

theatre; Nicholas I receives the Persian ambassador to take an<br />

apology for the murder of Russian diplomats, among them<br />

Griboedov, in Tehran; and Nicholas II has breakfast with his wife<br />

Alexandra and his children, including Anastasia and the hemophiliac<br />

Alexis. This sequence of historical events ends with the finale, the<br />

last ball in the Winter Palace in 1913. On the other hand there are<br />

characters of different epochs, rupturing the neat chronology of the<br />

Romanov dynasty: Valerii Gergiev, the conductor of the Mariinskii<br />

Theatre, conducts the mazurka from Glinka’s Life of a Tsar. Past and<br />

current directors of the Hermitage museum discuss problems of<br />

conservation, and worry about the authorities’ lack of understanding<br />

of cultural heritage. Contemporary visitors stand next to historical<br />

characters in the museum. Moreover, time passes at the speed of<br />

breath: the empress Catherine is a young woman during the rehearsal<br />

at the Hermitage Theatre; a few rooms later she is an old woman,<br />

running off into the Hanging Gardens to get some fresh air. Some<br />

rooms contain the future of the past: a room with empty hoar-frosted<br />

frames remind of the blockade of Leningrad during World War II<br />

when the canvasses were evacuated to Sverdlovsk (Ekaterinburg).<br />

The journey through the space of the past is a journey through time,<br />

but the two never intersect. History possesses chronology, while<br />

existing simultaneously with the present and other epochs. The<br />

Hermitage is an enclosed space, containing past and present,<br />

preserving the past for the future. It is the preservation of the past for<br />

the present which interests both the Hermitage museum and the filmmaker<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong>.<br />

The Hermitage functions as the ark of Russian cultural<br />

heritage, containing one of the largest collections of paintings and the<br />

treasures of the Romanov Empire. In travelling through Russia’s past<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong> aims to recreate its splendour. He draws, however,<br />

exclusively on that period of Russian history when the country was<br />

most exposed to European influences. He excludes the period before<br />

Peter the Great (the tsar who opened Russian to the West and founded<br />

the city of Petersburg as the ‘window onto Europe’) and ends his<br />

account with the last tsar, Nicholas II, excluding eighty years of<br />

Soviet rule and ten years of post-Soviet Russia. <strong>Sokurov</strong> refuses to<br />

see continuity from the Russian Empire to Soviet rule, as well as from<br />

the Kievan to the Russian Empire; moreover, he is not at all<br />

concerned with the politics of the time. <strong>Sokurov</strong> thus renounces the<br />

twentieth century as unworthy of depiction and lacking cultural value.<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong> guides his viewer on the journey through the Hermitage not<br />

with an authorial narrative, but through the character of the Marquis<br />

de Custine, the French aristocrat who visited Russia in 1839 in an<br />

attempt to find there a justification for an absolute monarchy. He<br />

returned to France a convinced republican. Custine’s account of his<br />

visit to Russia brought him success as a writer, while his harsh and<br />

cynical account of Russian despotism was banned in Russia. Custine<br />

finds Russia a terrifying police state, a country where people lie<br />

bluntly to the foreign visitor and erect a façade of splendour and<br />

entertainment to hide chaos, where the ruling despot is adored by his<br />

slaves, who live only to achieve salvation of their misery through<br />

salvation in death, where neither the church has any moral authority<br />

nor nobility any duties. Russia is a country that lacks a national<br />

identity, imitating Europe instead. Using Custine as prism for a view<br />

on Russian history and culture, we are invited to acknowledge in<br />

Russian history only those elements that are pale imitations of<br />

European culture and history. At the end of the twentieth century<br />

nothing of value remains of Russia. Russia without its European

connection is void. Russia is neither part of Asia nor its master. The<br />

final image of the film leads from the ‘ark’ (Hermitage) to the sea<br />

(the Neva) – a murky, foggy, grey patch of marshland rises outside<br />

the entrance to the Hermitage:<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong> says farewell to Europe as he leaves the year 1913,<br />

and thus annihilates Russia’s history that ensues. What remains in the<br />

ark is the splendid past, eclipsing the horrors of the Soviet regime, but<br />

also the Russian art movements of the 19th and early <strong>20</strong>th century.<br />

Having severed its links with Europe, the ship is destined to sail<br />

forever in the limbo between Europe and Asia.<br />

While creating a masterpiece of technological mastery of<br />

time <strong>Sokurov</strong> creates an unbridgeable abyss between Europe and<br />

Asia, placing Russia clearly in a European context, of which it is a<br />

poor imitator, a chimera, a ghost ship. The Hermitage is the ark,<br />

carrying Russia’s cultural heritage; as such, it harbours vast<br />

collections of Asian, Oriental and Russian art as well as Western<br />

European art. <strong>Sokurov</strong> chooses to ignore the Oriental/Asian part of<br />

the ark’s content, concentrating exclusively on the parts that deprive<br />

Russia of its own/another cultural identity and bear witness to the<br />

imported cultural heritage from Western Europe.<br />

Rob Blackwelder in First Person, Past Tense:<br />

There is a genius to the experimental and utterly surreal historical<br />

epic "Russian Ark" that has nothing to do with the fact that it was<br />

shot in one uninterrupted, mind-boggling 93-minute take that passes<br />

dreamlike through three centuries of Russia's royal past.<br />

If this movie had been made traditionally -- several takes of<br />

every scene edited together with close-ups, two-shots, etc. -- its story<br />

would still be enthralling as it follows a traveler (or is he a ghost?) set<br />

adrift in time inside the breathtakingly grand Hermitage Museum of<br />

St. Petersburg, the former Winter Palace of the czars.<br />

As writer-director Alexander <strong>Sokurov</strong> ("Mother and Son")<br />

turns you, the viewer, into this traveler with psychologically seamless<br />

first-person cinematography (by Tilman Buttner “Run Lola Run”),<br />

the film becomes almost literally transporting, bringing alive the<br />

courts of bygone Catherines and Nicholases as it whisks you from<br />

room to room and era to era.<br />

Guided by an eccentric French stranger (Sergey Dreiden), a<br />

similarly limboed 19th century diplomat who is able to interact with<br />

the people of the various centuries in a way the traveler cannot, we're<br />

witness to incredibly tangible moments of history -- some random,<br />

some pivotal -- as we pass through the opulent halls and ballrooms of<br />

the vast palace.<br />

Leaving an 18th century party through a dark staircase leads<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong>—<strong>RUSSIAN</strong> <strong>ARK</strong>—7<br />

to an ornate private theater where a play is being performed for<br />

Catherine I, 100 years before. The traveler and the stranger later<br />

observe silently as Peter the Great belittles a subservient courtier, and<br />

subsequently debate history's perception of the man as a tyrant.<br />

They're surprised to pass into the present momentarily and discuss the<br />

museum's magnificent collection with modern patrons before opening<br />

a door and finding themselves in the middle of a the Nazi siege on<br />

Leningrad (which was the city's name during the Soviet era).<br />

And on it goes, in one fluid steadycam shot without a single edit,<br />

through a dozen eras of Russian history; through scores of<br />

magnificent rooms with decorated ceilings and marble walls; through<br />

hundreds upon hundreds of lavishly costumed extras; and through<br />

curious philosophical discussions between the two unwitting<br />

companions about Russian history and culture.<br />

The logistical feats of this movie are unprecedented -- imagine the<br />

planning involved in having a 150-room museum filled with<br />

hundreds of people in period costume (including four live orchestras),<br />

all of whom must be in precisely the right places at the right times<br />

because there can be no second take. But "Russian Ark" is so vivid<br />

and spellbinding that such rational thoughts will be the farthest thing<br />

from your mind as you're drawn into the eras and events that unfold<br />

before your eyes.<br />

The history is fascinating, whether you're familiar with<br />

Russia's past or not (although I'm sure the more one knows, the better<br />

it gets), and the journey of its characters as they slip between epochs<br />

is engrossingly bizarre.<br />

The performance of Dreiden as the aged, unruly-haired and<br />

slightly Puckish stranger -- an eerily calm oddity in a long, capsleeved<br />

winter coat who keeps his arms folded formally behind his<br />

back except when struck with the impulse to be flamboyantly<br />

theatrical -- is strange enough to keep the traveler (and by extension<br />

us filmgoers) off balance. But he is congruent enough in the movie's<br />

living history to occasionally merge into a period party crowd, for<br />

example, leaving us momentarily lost in time.<br />

But more importantly, <strong>Sokurov</strong>'s camera behaves exactly as<br />

any of us might if we found ourselves invisibly enveloped in another<br />

time and place. Fascinated by every detail, sometimes we the traveler<br />

become distracted, staring at the tense hands of a royal guard. Other<br />

times we watch in amazed bewilderment as a museum employee<br />

backs away from us in a startled manner. What does he see? During a<br />

19th Century ball, we float through the dancers, then move across the<br />

room to see the view from the orchestra stage (providing the film's<br />

one visual mistake for the detail-oriented -- a musician wearing<br />

modern glasses).

"Russian Ark" may be an astonishing achievement in<br />

filmmaking, but what makes it unforgettable is <strong>Sokurov</strong>'s ability to<br />

draw us so deeply into the vibrant worlds he conjures -- without any<br />

cinematic slight of hand -- that the technical aspects of the picture<br />

<strong>Sokurov</strong>—<strong>RUSSIAN</strong> <strong>ARK</strong>—8<br />

become invisible and forgotten.<br />

Quite simply, I've never seen -- or even imagined -- anything<br />

like it.<br />

COMING UP IN THE FALL <strong>20</strong><strong>12</strong> BUFFALO FILM SEMINARS <strong>XXV</strong>:<br />

Nov 27 WHITE MATERIAL Claire Denis <strong>20</strong>09<br />

Dec 4 A SEPARATION Asghar Farhadi <strong>20</strong>11<br />

CONTACTS:<br />

...email Diane Christian: engdc@buffalo.edu<br />

…email Bruce Jackson bjackson@buffalo.edu<br />

...for the series schedule, annotations, links and updates: http://buffalofilmseminars.com<br />

...to subscribe to the weekly email informational notes, send an email to addto list@buffalofilmseminars.com<br />

....for cast and crew info on any film: http://imdb.com/<br />

The Buffalo Film Seminars are presented by the Market Arcade Film & Arts Center<br />

and State University of New York at Buffalo<br />

with support from the Robert and Patricia Colby Foundation and the Buffalo News<br />

Spring <strong>20</strong>13 Buffalo Film Seminars <strong>XXV</strong>I (preliminary screening list):<br />

George Pabst, Pandora’s Box 1929<br />

Charlie Chaplin, The Great Dictator 1940<br />

Marcel Carné, Les visiteurs du soir1942<br />

Jean Vigo, L’Atalante 1947<br />

Orson Welles, Touch of Evil 1958<br />

Kon Ichikawa, Revenge of a Kabuki Actor 1963<br />

John Huston, Fat City 1972<br />

Volker Schlöndorf, The Tin Drum 1979<br />

Mike Leigh, Naked 1994<br />

Michael Cimino, Heaven’s Gate <strong>20</strong>00<br />

Paul Thomas Anderson, Punch-Drunk Love <strong>20</strong>02<br />

Sidney Lumet, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead <strong>20</strong>07<br />

Zack Snyder, Watchmen <strong>20</strong>09<br />

Marleen Gorris, Within the Whirlwind <strong>20</strong>09