Enric MirallEs + BEnEdETTa TagliaBuE - collage and architecture

Enric MirallEs + BEnEdETTa TagliaBuE - collage and architecture

Enric MirallEs + BEnEdETTa TagliaBuE - collage and architecture

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

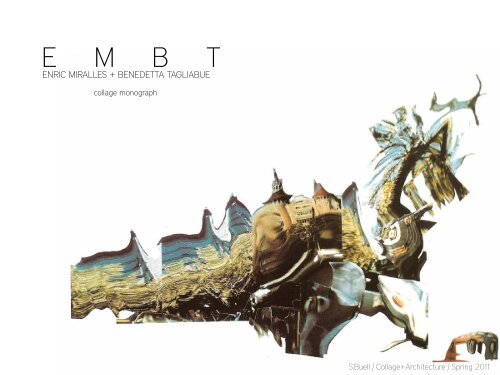

E M B T<br />

<strong>Enric</strong> <strong>MirallEs</strong> + <strong>BEnEdETTa</strong> <strong>TagliaBuE</strong><br />

<strong>collage</strong> monograph<br />

s.Buell | <strong>collage</strong>+<strong>architecture</strong> | spring 2011

E M B T<br />

<strong>Enric</strong> <strong>MirallEs</strong> + <strong>BEnEdETTa</strong> <strong>TagliaBuE</strong><br />

“a <strong>collage</strong> is a document that fixes a thought in a place, but it fixes it in a vague way, deformed <strong>and</strong> deformable; it fixes a reality in<br />

order to be able to work with it.”<br />

“When we turn a pocket inside out, the objects fall <strong>and</strong> we gather them.”<br />

-E. Miralles<br />

in 1992, <strong>Enric</strong> Miralles <strong>and</strong> Benedetta Tagliabue joined to create their namesake firm, EMBT. Their <strong>collage</strong> <strong>and</strong> photomontage work was an integral part<br />

of their partnership’s design development. The built <strong>and</strong> paper projects resonate with the theme of juxtaposing disparate elements of a place through the<br />

actions of excavation, addition, <strong>and</strong> reconfiguration.<br />

a study of <strong>Enric</strong> Miralles’ (<strong>and</strong> later, EMBT’s) <strong>collage</strong>s reveals a development of his representational methods <strong>and</strong> means. although the methods have<br />

evolved, a few constants have remained:<br />

First, the importance of manipulation of the perimeter of a composition is a persistent theme. “These <strong>collage</strong>s, like a puzzle, represent a space in a<br />

way that repeats the process of making a project itself. They are like a surprise, continually offering new definitions of the limits <strong>and</strong> contours.” Benedetta<br />

Tagliabue reflects on the beginnings of the cut-outs of the firm: “The very first cut-outs, around 1990, were done simply to eliminate an unwanted<br />

background. But later the scissors became a kind of liberating tool, creating the illusion that the building, in its final, constructed form, could still be worked<br />

on, varied. They seemed to bring the projects back to the drawing board.”<br />

second, there is an insistent curiosity about perspective, point of view, <strong>and</strong> simultaneity in the <strong>collage</strong>s. The destabilization of perspective through<br />

panoramic assemblages <strong>and</strong> unsuspected adjacencies recur over the years. The multiplicity of their photomontages as an assemblage of views is described<br />

as, “aim[ing] to fix, in a single view, all the different images which accompany the eye as it moves along the profiles <strong>and</strong> sections. They attempt to explain<br />

a complete <strong>and</strong> simultaneous kind of perception, to convey all knowledge contained in all the drawings <strong>and</strong> perspectives of a project.”<br />

This monograph traces the lineage of the <strong>collage</strong> work of <strong>Enric</strong> Miralles, from his beginnings in the late 1970’s through his collaboration with Benedetta<br />

Tagliabue (EMBT), <strong>and</strong> until his death in 2000. Today, Benedetta Tagliabue still practices in Barcelona, <strong>and</strong> continues to use <strong>collage</strong> <strong>and</strong> photomontage as<br />

a method of exploring design.<br />

s.Buell | <strong>collage</strong>+<strong>architecture</strong> | spring 2011

[BT][EM]<br />

<strong>TagliaBuE</strong><br />

Born in Milan 1963<br />

graduated from the university of Venice 1989<br />

Joined <strong>Enric</strong> Miralles’ studio<br />

Took leadership of EMBT<br />

igualada cemetary 1985-1996<br />

[EM]<br />

BacKground + oVErViEW<br />

<strong>MirallEs</strong><br />

1955: Born in Barcelona<br />

1974: graduated from ETsaB (Escuela Técnica superior de arquitectura de Barcelona)<br />

1978-1987: Works as an apprentice for Piñon <strong>and</strong> Vallaplana in Barcelona<br />

1987: Presented his doctoral thesis, “Things seen to the right <strong>and</strong> left (Without glasses)”<br />

1987-1989: collaboration with carme Pinós<br />

1990: Begins working as director <strong>and</strong> professor of the Master class at städelschule of Frankfurt<br />

1991: Began working with Benedetta Tagliabue, served at the “Kenzo Tange chair” professor at Harvard<br />

2000: His death was met with a flurry of publications <strong>and</strong> accolades<br />

scottish Parliament 2004<br />

[EM]BT<br />

scottish Parliament 2004<br />

[EM]BT<br />

Mercat santa catalina<br />

1997-2005<br />

[EM]BT

figure 1.<br />

PErsPEcTiVal BEginnings: 1976-<br />

Miralles’ focus on perspective <strong>and</strong> fragmentation evidenced his doctoral research. in his thesis, he discusses drawing as a collection of fragments. He describes the<br />

making of the drawings as, “the beginning of the dialogue between thought <strong>and</strong> construction.” although line drawings, the perspectives explore fragments of other<br />

buildings to make space <strong>and</strong> the transparency of these pieces. in the drawings, the transparency is literal, not phenomenal. His focus appears to be on the creation<br />

of absence through layering. He also employed the use of photocopies (figure 1) to explore the distance between the immediacy of drawing <strong>and</strong> the creation of an<br />

image. “ now these drawings are cuttings from photocopies; i try to see them as though for the first time: they are enlargements that distance themselves from<br />

the h<strong>and</strong>, from the curving arch of the wrist, articulations whose movement is repeated continuously in drawing (no matter how much one tries to get away from<br />

them).” He compares his thesis to “the enthusiastic awareness of eighteenth century travelers, in whom active contemplation is conflated with creation.” This kind<br />

of active contemplation aligned with creation also describes his <strong>collage</strong> making.

figure 2.<br />

igualada cEMETary 1985-1996<br />

The igualada cemetary project began with the partnership of Miralles with carme Pinós. However, the project took eleven years (1985-1996) to complete, <strong>and</strong><br />

in that time, Pinós left Miralles <strong>and</strong> Tagliabue became a partner. Much of the work was completed in 1985 <strong>and</strong> 1986, but the chapel was designed five years<br />

after the first phase of construction. The design of the chapel marks the beginning of Miralles’ use of photomontage. using photographs of the completed project,<br />

Miralles revisited his work by cutting into the images. Miralles said, “in this way we returned to the initial character of the building, tying together the distant stages<br />

of beginning <strong>and</strong> end, re-establishing the direct relationship that exists almost independently of the development of the work.” Tagliabue states, “Within this<br />

framework, the built work is not the ‘main’ stage of the architectonic process, but simply another stage.”<br />

The cut-out images of the cemetery are single pieces of paper, with the negative space that surrounds the perimeter becoming a <strong>collage</strong>d element (figures 2,3).<br />

although some may require <strong>collage</strong> to be two or more elements juxtaposed, these ‘cut-outs’ use varied perimeters to engage the negative space in more than one<br />

way, therefore becoming <strong>collage</strong>s. Beyond the profile of the hills, the space is infinite, while at the bottom of the compositions the negative space is foregrounded,<br />

almost becoming an object itself.<br />

figure 3.

figure 6.<br />

osTHaVEn PorT ProJEcT 1992<br />

“The photomontages attempt to recapture the existence of the other river bank, the immaterial presence of other places, images of streets, windows of city<br />

dwellings: what exists <strong>and</strong> what could exist.”<br />

The use of photomontage <strong>and</strong> drawing fragments in the representation of the osthaven Port Project reveals the importance of “excavating” the ground in the<br />

project. a comparison of two <strong>collage</strong>s produced for the project reveals the use of photomontage as a means for underst<strong>and</strong>ing figure <strong>and</strong> ground in relation to<br />

the project’s context. in figure 5, the photos constitute the foreground of the proposal, the design, as well as the panoramic context. in figure 6, the photos play a<br />

different role, they inhabit the negative space of the water, adding context to what was blank in the first <strong>collage</strong>. This interplay between what is added, subtracted,<br />

covered <strong>and</strong> uncovered allows for the design’s details to remain ambiguous.<br />

figure 5.

BrEMErHaVEn 1993<br />

EMBT’s use of photomontage as a ground for drawing fragments is used in the Bremerhaven Port<br />

reuse competition Proposal. The <strong>collage</strong>s foreground juxtaposed plans, elevations, <strong>and</strong> sections with<br />

fragmented images beyond (figure 3). The photomontages are used as a contextual ground, while<br />

the placement <strong>and</strong> scale of the drawing fragments exhibit the generative aspects of the studies.<br />

“our response was to superimpose a temporal complexity on this unique place with a series of<br />

narrative proposals.” in a later model of the project, photomontage is used in a more conventional<br />

way, with the perimeter becoming less irregular than the previous drawings <strong>and</strong> operating more as a<br />

taciturn base for the articulate model (figure 4). although the photomontage of this model is more<br />

reserved than the base of the previous <strong>collage</strong>s, it is not silent. The perimeter is carefully trimmed,<br />

sometimes tracing the bulwarks of the canal, <strong>and</strong> other times shearing through nearby buildings,<br />

bringing attention to certain edge conditions important to the project.<br />

as a note, the photomontages predate digital automation <strong>and</strong> are arranged by h<strong>and</strong> with developed<br />

photographs. Therefore, the act of making the <strong>collage</strong>s is different than the ubiquitous means of<br />

making panoramas with scripts on a computer. This analog type of making hearkens back to how<br />

Miralles described the drawings he created for his doctoral thesis, “the beginning of the dialogue<br />

between thought <strong>and</strong> construction.”<br />

figure 3.<br />

figure 4.

figure 7.<br />

saragossa MusEuM oF conTEMPorary arT 1994<br />

similarly, the method of using photomontage as a panoramic ground for drawing fragments is used in the representation of the Proposal for the saragossa<br />

Museum of contemporary art (1994). Miralles’ describes the spaces of the project: “These spaces slide in front of existing neighborhood constructions. The outline<br />

of this complex of spaces is confused with that of the city.” This can be seen on the right side of figure 7, where the drawing fragments move between the<br />

negative space <strong>and</strong> the photomontage. on the left side of the composition, multiple views of the same a model are strung together, revealing a non-perspectival<br />

view of the context. The coincident presence of a panorama <strong>and</strong> a bird’s eye view in this <strong>collage</strong> reveal the firm’s curiosity about simultaneous perception. “These<br />

montages aim to make one forget the ways of representing <strong>and</strong> thinking about the physical reality of things characteristic of the perspectival tradition. in a certain<br />

sense, they are like simultaneous sketches, like multiple <strong>and</strong> distinct visions of one single moment.” He continues, “a <strong>collage</strong> is a document that fixes a thought<br />

in a place, but it fixes it in a vague way, deformed <strong>and</strong> deformable; it fixes a reality in order to be able to work with it.”

figure 8.<br />

HosTalETs ciVic cEnTEr ProJEcT 1990<br />

in the Hostalets civic center Project in Balenyá, spain, photomontage is used to document the construction process (figure 8). “These partial, lateral views<br />

constitute a process parallel to the growing stimulus to compile the documentation produced by a project. in addition, these deformations have the capacity to<br />

render the content of the projects explicit.” EMBT seems moved to make sense of the photographic evidence of construction while compelled by the dialogue<br />

between the generative nature of the arrangement of the indexical photographs.

figure 9. figure 10.<br />

roME ParocHial cEnTEr ProPosal 1994<br />

For EMBT, Photomontage is often an arrangement of photographs of a place, with the constituent elements of the <strong>collage</strong> taken from the same location. However,<br />

in the rome Parochial center competition (1994), the <strong>collage</strong>s are of a different nature. The <strong>collage</strong>s are used to explore the idea of the building as a continuous<br />

circle, or an animal eating its tail. This is explored with the assembly of unrelated images. in figure 9, a fish is placed on the site, scaled to the building, resembling<br />

the form, but bringing its own set of meanings. in figure 10, bread, beans, feet, <strong>and</strong> a glass are composed on an image of the site. The proposal was not accepted,<br />

<strong>and</strong> furthermore, the organization never contacted the firm again.

figure 11.<br />

BuggErru TourisT VillagE ProJEcT 1994<br />

in the photomontages for the osthafen Port reuse competition <strong>and</strong> Hostalets civic center Project, the module of the printed photograph guides the perimeter of<br />

the composition. However, in the Buggerru Tourist Village Project in sardinia (1994), the images that are used as the ground begin to act as texture rather than<br />

panorama <strong>and</strong> the perimeter of the composition is dramatically modified from the orthogonal module of the photographic print (figure 11). This may be the next<br />

step in the evolution of the <strong>collage</strong>s produced by the firm, or may also be because of the nature of the projects. While the osthafen <strong>and</strong> Hostalets projects are<br />

urban infill projects, the Buggerru project is rural, with the an undulating l<strong>and</strong>scape being the primary ground for design.

inTErnaTional gardEn Fair in drEsdEn 1995<br />

in the proposal for the international garden Fair in dresden (1995), photomontage brings into question its role as representation or as design. The photomontage in<br />

figure 12 illustrates the modeling approach of using flower petals as a means for developing the design. are the photographs representing the model a the primary<br />

mode of design development, or is the photomontage crucial to the design as well? This is similar to the question of a record of performance art. is the performance<br />

the art piece, or is the record the art piece?<br />

figure 12.

‘HEaVEn’ insTallaTion 1994-1995<br />

figure 13.<br />

The ‘heaven’ installation at Tateyama Park-Museum in Japan (1994-1995), reveals a <strong>collage</strong>-like fascination with layering <strong>and</strong> multiplicity. The project, comprised<br />

of of suspended copper serpentine b<strong>and</strong>s, investigates the density of light <strong>and</strong> shadow through layering. The dynamism <strong>and</strong> multiplicity of this type of layering<br />

can parallel EMBT’s approach to <strong>collage</strong> <strong>and</strong> design.

figure 14.<br />

Prado MusEuM ExTEnsion coMPETiTion 1995<br />

The representations of the Prado Musem Extension competition in Madrid (figures 14, 15) appear to provide a foil to the dreseden international garden Fair<br />

Proposal (Figure 12). The <strong>collage</strong>s use images of gardens <strong>and</strong> a constructed model to represent the design. in this case, the model is not only being represented,<br />

but reconfigured. unlike the proposal for the garden Fair in dresden, the photographs of the model are trimmed, reconfigured, rescaled in respect to one another.<br />

The multiplicity of views, from almost planar to bird’s eye exhibits a conscious rethinking of the model.<br />

figure 15.

cHEMniTz sPorTs cEnTEr 1995<br />

figure 16.<br />

similar to the Prado Museum Extension (figures 14, 15), the reconfiguration of conventional architectural representation through photomontage is evident in the<br />

representation of the chemnitz sports center (figure 16). rather than presented as a singular drawing, the representation is fractured into modules similar to printed<br />

photographs. These modules are loosely assembled, destabilizing otherwise continuous lines <strong>and</strong> questioning the parts to whole relationship of a perspectival<br />

rendering.

figure 17.<br />

THEssalonoKi Bay MariTiME sTaTion 1996<br />

The plan <strong>collage</strong> of the Thessalonoki Bay Maritime station (figure 17) is yet another variation on the use of photomontage. like the contextual representation<br />

of the Bremerhaven Port reuse competition model (figure 4), photography is used as the base of the model. However, unlike this Bremerhaven model, the<br />

images are not planar, but rather panoramic, showing 360 degrees of vision from the end of a pier. like the Bremerhaven representation, the addition of thick<br />

materials brings the <strong>collage</strong> closer to a model than a two-dimensional composition. The interplay of the photomontage <strong>and</strong> light is caused by the shadows from<br />

the suspension of string above the substrate. This three dimensionality of a linear gesture resonates in the <strong>architecture</strong> of earlier projects, such as the Takaoka<br />

station access (figure 18), the unazuki Meditation Pavilion (figure 19).<br />

figure 18.<br />

figure 19.

figure 20.<br />

nEW rEalE THEaTEr 1996<br />

figure 21.<br />

in the proposal for the new reale Theater in copenhagen, (1996) the <strong>collage</strong> produced exhibits EMBT’s interest in context as well as the introduction of new<br />

techniques to their <strong>collage</strong> making. Miralles states, “it is necessary to respect the rich urban context of this crossroads site before beginning to weave a new theater<br />

into the city. The <strong>collage</strong> illustrates a type of crossroads, or a nexus of two almost-perpendicular paths. The use of <strong>collage</strong> to illustrate a designed perspective in an<br />

almost pictoral way is new in the collection of work (figure 20). unlike previous projects, like the Hostalets civic center construction, photomontage was used to<br />

document existing perspectives, or reconfigured images to construct a bird’s eye representations. The most similar representation to this <strong>collage</strong> is the osthaven<br />

vignettes that use drawing fragments on an existing panoramic photomontage. in addition, the perimeter of the copenhagen <strong>collage</strong> is cropped to a rectangle,<br />

unlike many of the other photomontages where the perimeter is determined by the positioning of the modules of individual photographs. although the materials<br />

<strong>and</strong> means of the <strong>collage</strong> are not detailed, the transparency <strong>and</strong> repetition of constituent pieces of the <strong>collage</strong> suggest that digital means may have been used.<br />

unlike previous analog <strong>collage</strong>s, the flattening <strong>and</strong> repetition of the scale figures compared with the texture of the overlapping photographs on the left side of the<br />

composition suggest a new type of experimentation with a variety of media. This introduction of digital means to representation is also evident in the illustration<br />

of the interior of the theater (figure 21). similarly, the view is cropped to a rectangle, <strong>and</strong> the contextual background is a digital rendering, as exhibited by the light<br />

patterns on the left wall, pixel-like resolution, <strong>and</strong> cyMK coloration of the sculptural elements.

[E M] B T<br />

<strong>Enric</strong> <strong>MirallEs</strong> + <strong>BEnEdETTa</strong> <strong>TagliaBuE</strong><br />

figure 22.<br />

figure 23.<br />

The new reale theater is one of the last completed projects by <strong>Enric</strong> Miralles before his death. although the scottish parliament <strong>and</strong> the Mercado de santa caterina<br />

rely heavily on his influence, he did not see their completion. The scottish parliament project marks Miralles’ emergence onto the super-architect scene. This<br />

commission is linked to a new kind of note taking for Miralles. He adopted larger sketchbooks <strong>and</strong> glue as traveling companions to more rigorously document his<br />

life. The sketchbooks are filled with precise <strong>collage</strong>s <strong>and</strong> notes, organized for posterity. after Miralles’ death, Tagliabue took control of the firm, completing the<br />

unfinished projects, <strong>and</strong> continues to drive a successful practice today. Photomontage, although still present in the in desing process of the firm, has moved from<br />

physical ubiquity to a broader design approach. in short, after Miralles’ death, <strong>collage</strong>s do not seem to be made as often. However, <strong>collage</strong> does remain a generative<br />

<strong>and</strong> representational device for the firm, but the nature of the photomontage has shifted from a more abstracted dialogue between perspective <strong>and</strong> perimeter<br />

to the use of image for its meaning <strong>and</strong> form. For example, the conceptual <strong>collage</strong>s for the comic <strong>and</strong> animation Museum in china (figure 22) rely heavily on<br />

imagery, with color <strong>and</strong> texture playing a different role than in earlier compositions. similarly the <strong>collage</strong> for school of Music in g<strong>and</strong>ia, spain (figure 23) uses the<br />

imagery of instruments more as a diagram of important urban connections <strong>and</strong> their programmatic symbolism. The <strong>collage</strong>s appear to be less generative; instead<br />

of suspending exactness, they seem demonstrative. Miralles described the distracted gaze as a tool for design: “My working method is closely linked to the idea of<br />

looking about or being distracted. once the problem has been set, the next step is to almost forget about the ultimate aim about what you are doing, almost as a<br />

means of distraction…you move forward through successive beginnings.”<br />

This monograph focuses on the beginnings of the <strong>collage</strong> work of the firm EMBT as traced back to the early work of <strong>Enric</strong> Miralles. There is some significance of<br />

the continuity of <strong>collage</strong>s before Tagliabue joined forces with Miralles <strong>and</strong> the discontinuity of the <strong>collage</strong> making after his death. although Benedetta undoubtedly<br />

had a significant influence on the <strong>collage</strong> process, <strong>Enric</strong> Miralles’ approach to photomontage <strong>and</strong> its influence on his design thinking is unique.

sources:<br />

E M B T<br />

<strong>Enric</strong> <strong>MirallEs</strong> + <strong>BEnEdETTa</strong> <strong>TagliaBuE</strong><br />

“EMBT 2000-2009: <strong>Enric</strong> Miralles Bendetta Tagliabue, afterlife in progress” El croquis, 144 (2009)<br />

“EMBT: <strong>Enric</strong> Miralles Bendetta Tagliabue – arquitectes associats” accessed March 3, 2012. http://www.mirallestagliabue.com/<br />

“EMBT Miralles Tagliabue” aa: arquitecturas de autor, (2006)<br />

“EMBT 1983-2000” El croquis, 100-101 (2002)<br />

Miralles, <strong>Enric</strong> <strong>and</strong> Bendetta Tagliabue, <strong>Enric</strong> Miralles: Mixed Talks (new york: academy Editions, 1995)<br />

Tagliabue, Bendetta <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enric</strong> Miralles, <strong>Enric</strong> Miralles: Works <strong>and</strong> Projects, 1975-1995 (new york: Montacelli Press, 1996)<br />

zabalbeascoa, anatxu <strong>and</strong> Javier rodríguez Marcos, Ed, Mirrales Tagliabue, Time <strong>architecture</strong> (corte Madera, ca: ginko Press, 1999)<br />

s.Buell | <strong>collage</strong>+<strong>architecture</strong> | spring 2011