The Transmission and Impact of the Hadhrami and Persian ... - Rihlah

The Transmission and Impact of the Hadhrami and Persian ... - Rihlah

The Transmission and Impact of the Hadhrami and Persian ... - Rihlah

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Transmission</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Impact</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> Lute-Type Instruments<br />

on <strong>the</strong> Malay World<br />

by<br />

Larry Francis Hilarian<br />

Musical instruments have always accompanied sea-fearers as entertainment artifacts in <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

long sea voyages. Along <strong>the</strong> grain <strong>of</strong> politics, conquests <strong>and</strong> economic exploits, some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se<br />

instruments have become identified as cultural icons amongst <strong>the</strong> communities so linked to this trade,<br />

mercantilism <strong>and</strong> adventure. <strong>The</strong> main focus <strong>of</strong> this paper is on <strong>the</strong> transmission <strong>and</strong> adaptation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Hadhrami</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> lute-type instruments commonly known as <strong>the</strong> gambus in alam melayu 1<br />

(Malay world). <strong>The</strong> gambus, although not <strong>of</strong> Malay origin, shares “kinship” ties not only with <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Hadhrami</strong> qanbus (lute) but also <strong>the</strong> European lute, Spanish guitar, <strong>Persian</strong> barbat, Greek bouzouki,<br />

Chinese pipa, Japanese biwa <strong>and</strong> also many o<strong>the</strong>r Central Asia <strong>and</strong> Eastern European lute<br />

instruments. This paper will also examine <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>and</strong> influences <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> musical <strong>and</strong><br />

cultural practices on <strong>the</strong> various aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malay Muslim society.<br />

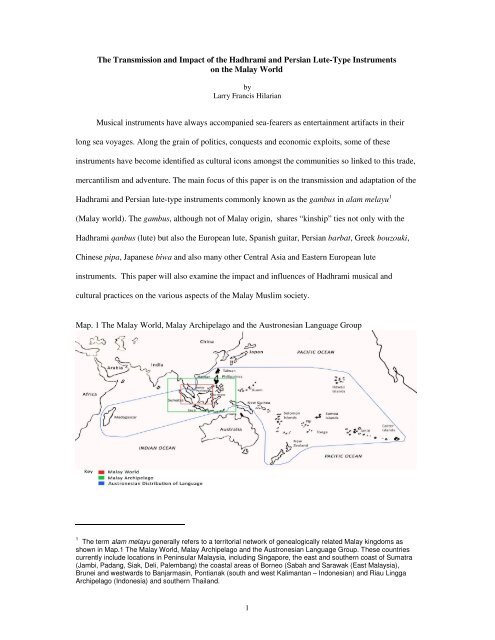

Map. 1 <strong>The</strong> Malay World, Malay Archipelago <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Austronesian Language Group<br />

1 <strong>The</strong> term alam melayu generally refers to a territorial network <strong>of</strong> genealogically related Malay kingdoms as<br />

shown in Map.1 <strong>The</strong> Malay World, Malay Archipelago <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Austronesian Language Group. <strong>The</strong>se countries<br />

currently include locations in Peninsular Malaysia, including Singapore, <strong>the</strong> east <strong>and</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn coast <strong>of</strong> Sumatra<br />

(Jambi, Padang, Siak, Deli, Palembang) <strong>the</strong> coastal areas <strong>of</strong> Borneo (Sabah <strong>and</strong> Sarawak (East Malaysia),<br />

Brunei <strong>and</strong> westwards to Banjarmasin, Pontianak (south <strong>and</strong> west Kalimantan – Indonesian) <strong>and</strong> Riau Lingga<br />

Archipelago (Indonesia) <strong>and</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn Thail<strong>and</strong>.<br />

1

<strong>The</strong> Definition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> word “Gambus” <strong>and</strong> its Ambiguity<br />

<strong>The</strong> word “gambus” refers to two distinctive types <strong>of</strong> lute instruments found in alam<br />

melayu. 2 Both <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se types are known simply as “gambus” to <strong>the</strong> Malay Muslim community<br />

as shown in Plate (i) [a] Gambus Hadhramaut <strong>and</strong> Plate (i) [b] Gambus Melayu. 3<br />

Plate (i) [a] Gambus Hadhramaut Plate (i) [b] Gambus Melayu<br />

However, both instruments are also known at times by o<strong>the</strong>r names to traditional players,<br />

makers <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> wider community. 4 <strong>The</strong> gambus that looks like <strong>the</strong> classical Arabian ūd can<br />

be referred to as gambus Hadhramaut, sometimes as gambus Arab or ūd. <strong>The</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r form <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> instrument, which is much smaller, but appears similar to <strong>the</strong> Yemeni qanbus (sometimes<br />

2 Capwell (1995:80) describes <strong>the</strong> multiform nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gambus as two distinctive types <strong>of</strong> plucked lutes<br />

bearing <strong>the</strong> same name, which are also found in Indonesia.<br />

3 <strong>The</strong> gambus usually performed with <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> three or more marwas or kompang instruments. Marwas are<br />

small double-headed frame-drums, which come in three sizes. Two skins on each side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> marwas cover <strong>the</strong><br />

instrument, which have a diameter <strong>of</strong> between 14 <strong>and</strong> 20 cm. It is laced with lea<strong>the</strong>r <strong>and</strong> has metal studs nailed<br />

around its frame. Goatskin is used for <strong>the</strong> membrane <strong>and</strong> jackfruit-wood is used for <strong>the</strong> frame <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> instrument.<br />

Kompang are single-headed frame-drums <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y also come in three different sizes. <strong>The</strong>ir sizes could range<br />

from 15 to 40 cm. <strong>The</strong> frame is also made from jackfruit-wood <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> membrane is from goatskin <strong>and</strong> cowhide.<br />

<strong>The</strong> marwas is used mainly in <strong>the</strong> zapin ensemble whereas <strong>the</strong> kompang is used extensively in many Malay<br />

music genres, most importantly in Malay wedding processions <strong>and</strong> in <strong>the</strong> welcoming ceremonies (Hilarian: 2009).<br />

4 <strong>The</strong> Hornbostel <strong>and</strong> Sachs category for <strong>the</strong>se lutes would be: 321. 321 “Necked bowl lute”, a classification <strong>the</strong><br />

gambus Hadhramaut shares with <strong>the</strong> European lute, Greek bozouki, Chinese pipa, Arabic ūd <strong>and</strong> many o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

instruments. As for <strong>the</strong> gambus Melayu it can be classified under: 321.32 “Necked lutes - <strong>the</strong> h<strong>and</strong>le is attached<br />

to or curved from <strong>the</strong> resonator, like a neck”, translated by Baines <strong>and</strong> Wachmann (1961).<br />

2

called qabus, turbi, or tarab in Yemen, shown in Plate (ii) Qanbus from Yemen 5 is referred<br />

to as <strong>the</strong> gambus Melayu. 6<br />

Plate (ii) Qanbus from Yemen<br />

<strong>The</strong> term “gambus” when used to refer to <strong>the</strong> two types <strong>of</strong> lute instruments are still<br />

confusing <strong>and</strong> ambiguous. <strong>The</strong> earliest western documented source that I have come across<br />

in English, which records <strong>the</strong> word “gambus” is Sachs’ <strong>The</strong> History <strong>of</strong> Musical Instruments. 7<br />

Short lutes, carved out <strong>of</strong> a single piece <strong>of</strong> wood with no distinct neck <strong>and</strong> tapering towards<br />

<strong>the</strong> pegbox, are found first in Iran (Persia), <strong>the</strong> same country which afterwards became <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

centre; Elamic clay figures attributed to <strong>the</strong> eighth century B.C. show <strong>the</strong>m in rough<br />

outlines; <strong>the</strong> strings <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir attachment are not distinguishable. …..Islam migration <strong>and</strong><br />

5 I am grateful to Mr. Pierre d’Herouville for this photograph.<br />

6 Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Christian Poche told me that <strong>the</strong> gambus Melayu is probably from <strong>the</strong> Yemeni qanbus (personal<br />

communication: 4th July 1999) in Abbaye de Royaumont, France. <strong>The</strong> widely disseminated qanbus has various<br />

names: gabbus [gambusi] in Zanzibar, gabbus in Oman, gabusi or gambusi in <strong>the</strong> Comoros Archipelago, gabus<br />

in Saudi Arabia <strong>and</strong> kabosa in Madagascar. <strong>The</strong>se types <strong>of</strong> skin-bellied lute instruments are also known as<br />

kibangala or taarab in Mombasa <strong>and</strong> in <strong>the</strong> coastal areas <strong>of</strong> Kenya. Poche concluded that <strong>the</strong> term “qanbus”<br />

derives from <strong>the</strong> root “q-n”, <strong>of</strong>ten found in musical vocabulary <strong>of</strong> Semitic languages. <strong>The</strong> dropping <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> “n” from<br />

“qanbus” to “qabus” has led to erroneous speculation that <strong>the</strong> word originated as a mutation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Turkish kopuz,<br />

(qopuz, qupuz) a long-necked lute (baglama, saz) described by Farmer (1967:209) <strong>and</strong> Sachs (1940:252). See<br />

<strong>The</strong> New Grove Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Musical Instruments (Poche:1984:168). Also see Poche, Musiques du Monde<br />

Arabe (1994).<br />

7 German ethnomusicologist Curt Sachs was probably <strong>the</strong> first European scholar to have used <strong>the</strong> word<br />

“gambus” in his 1913 German publication <strong>of</strong> “Reallexikon der Musikinstrumente” (p.152) Georg Olm<br />

Verlagsbuch<strong>and</strong>lung Hildesheim 1964 Nachdruck der Ausgabe, Berlin, 1913 mit Genehmigung des Verlag Max<br />

Hesse. Later, Dutch ethnomusicologist Jaap Kunst used <strong>the</strong> word gambus in an article in 1934, describing <strong>the</strong><br />

gambus as a plucked pear-shaped lute. He concluded that <strong>the</strong> gambus is fairly common throughout <strong>the</strong> entire<br />

Malay Archipelago in strict Islamic areas. Kunst described it as having seven strings: three double-strung pairs<br />

<strong>and</strong> one low single string (1934). In ano<strong>the</strong>r article Kunst also mentioned that its (gambus) country <strong>of</strong> origin was<br />

<strong>the</strong> Hadhramaut region <strong>of</strong> Yemen where it is known as quopuz. This article appeared in “Two Thous<strong>and</strong> Years <strong>of</strong><br />

South Sumatra Reflected in its Music” (1952). Both reprints also appeared in Indonesian Music & Dance<br />

published by <strong>The</strong> Royal Tropical Institute/Tropenmuseum University <strong>of</strong> Amsterdam/Ethnomusicology Centre<br />

“Jaap Kunst”, (1994:170; 237).<br />

3

conquests carried this lute eastwards from Persia as far as Celebes, [Sulawesi] <strong>and</strong><br />

southwards to Madagascar. In all <strong>the</strong>se countries it has been called by a name probably <strong>of</strong><br />

Turkish origin, variously spelled as gambus, kabosa or qupuz (1940: 251-252).<br />

Sachs claims that <strong>the</strong> word “gambus” derived from <strong>the</strong> Arabic name qobus, lute-type<br />

instruments that are still used in Turkey, Hungary, Russia, Romania <strong>and</strong> some o<strong>the</strong>r places in<br />

Europe. He mentions that in Borneo this instrument is called gambus <strong>and</strong> in Zanzibar it is<br />

gabbus. He attributes that <strong>the</strong> instrument arrived in <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago as early as <strong>the</strong><br />

seventh century. Sachs based his <strong>the</strong>ories on <strong>the</strong> sickle-shaped peg-box, tracing <strong>the</strong>se types <strong>of</strong><br />

instruments to a kind <strong>of</strong> rebab still used in Borneo <strong>and</strong> Zanzibar (Panum: 1971). 8<br />

Sir Richard Winstedt (1960) in Kamus Bahasa Melayu (Malay Dictionary), R.J.<br />

Wilkinson (1955) in A Malay-English Dictionary, <strong>and</strong> also in ano<strong>the</strong>r st<strong>and</strong>ard edition <strong>of</strong><br />

Kamus Dewan (Malay Dictionary, 1998) all mentioned that <strong>the</strong> word gambus may be an<br />

Arabic loan word in <strong>the</strong> Malay language. 9 M.A.J. Beg (1982) did not mention <strong>the</strong> word<br />

gambus in his book on Malay neologism from Turkish-<strong>Persian</strong> words but referred to <strong>the</strong><br />

word barbat, a type <strong>of</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> origin pear-shaped lute. 10<br />

8 <strong>The</strong> etymological links to <strong>the</strong> terms “gambus” <strong>and</strong> “viola da gamba” have been puzzling to ethnomusicologists.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Grove Dictionary for Music <strong>and</strong> Musicians (vol: 19: 1980: 814) says that <strong>the</strong> derivative <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> word gambus is<br />

“obscure” <strong>and</strong> suggests it may have come from an Italian word to describe early European bowed-lute. However,<br />

I would argue that <strong>the</strong> Malay, Arabic <strong>and</strong> Turkish link seems equally possible.<br />

9 <strong>The</strong>se Malay dictionaries (Kamus Bahasa Melayu <strong>and</strong> Kamus Dewan) describe <strong>the</strong> word gambus although not<br />

quite accurately as 6 stringed lute <strong>of</strong> Arabian origin. With hindsight, <strong>the</strong> word gambus has no roots in Bahasa<br />

Melayu. This has been confirmed by <strong>the</strong> members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malay Language Unit at Nanyang Technological<br />

University/National Institute <strong>of</strong> Education, Singapore (personal communication: 1997).<br />

10 Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Henry Farmer states that <strong>Persian</strong> lexiconographers derived <strong>the</strong> word from bar (“breast”) <strong>and</strong> bat<br />

(“duck”), because its shape was like <strong>the</strong> breast <strong>of</strong> a duck. He also mentioned that 11 th century Arab scholar Majd<br />

al-Din Isn al Athir (d.1210) said it was “because <strong>the</strong> player upon it places it against his breast” (1931a:95). Dr.<br />

Jean Lambert commented that <strong>the</strong>re is no historical or iconographical evidence to show how <strong>the</strong> barbat looks <strong>and</strong><br />

historical treatises on <strong>the</strong> barbat are not explicit enough to draw conclusions about how it may have appeared (In<br />

a letter to me commenting on my research: December: 1999). I will argue that <strong>the</strong> depiction shown in Plate (iii [a]<br />

Sassanian lute player) provides convincing evidence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> lute barbat. <strong>The</strong> author is grateful to <strong>the</strong><br />

British Museum for <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> this picture.<br />

4

Plate (iii) [a] Sassanian Lute (barbat?) A.D. 224 Plate (iii) [b] Greco-G<strong>and</strong>hara lute A.D. 100<br />

<strong>The</strong> Malays may have adopted <strong>the</strong> generic term gambus to refer to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> barbat,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Arabian qanbus (qabus) <strong>and</strong> ūd, found in alam melayu. 11 <strong>The</strong> word gambus may<br />

originally have referred to a <strong>Persian</strong> lute with a pear-shaped body, skin belly <strong>and</strong> a “C”<br />

shaped peg-box as shown in Fig.1 “C” Shaped Pegbox. 12<br />

Fig. 1 “C” Shaped Pegbox<br />

<strong>The</strong> Early Migration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> Lute-Type Instruments<br />

11 This point about <strong>the</strong> probable Arabic word “gambus” being borrowed by <strong>the</strong> Malays to describe <strong>the</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> lute<br />

was unanimously <strong>the</strong> opinion expressed by Malay Language specialists at Nanyang Technological<br />

University/National Institute <strong>of</strong> Education in Singapore (personal communication: April 1997).<br />

12 While visiting <strong>the</strong> British Museum, I came across a silver plate [see Plate (ii[a]) showing a banqueting scene<br />

from <strong>the</strong> 3rd –7th century Sassanian Period (Persia [Iran]). This is <strong>the</strong> only evidence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> “barbat” in visual form<br />

that I have seen (16th May 2001). <strong>The</strong> design on <strong>the</strong> plate depicted a musician playing a lute-type instrument that<br />

looked similar to <strong>the</strong> gambus Melayu. This could also be <strong>the</strong> lute-type instrument that Farmer, During (1984) <strong>and</strong><br />

Zonis (1973) were referring to as <strong>the</strong> barbat from Persia. Similar lute instruments to those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sassanid period<br />

were also found during <strong>the</strong> Greco-G<strong>and</strong>hara [see Plate (ii[b]) period (c.100 A.D.) This picture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> G<strong>and</strong>hara<br />

lute was taken from Sachs (1940: plate IX (B):160) <strong>and</strong> Marcuse (1975: 410). <strong>The</strong>se pictorial facts on <strong>the</strong> barbat<br />

are some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> conclusive evidence, which match <strong>the</strong> documentary descriptions.<br />

5

<strong>The</strong>re are various hypo<strong>the</strong>se as to how <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong>-<strong>Persian</strong> lute-type instruments,<br />

now referred to as gambus Melayu <strong>and</strong> gambus Hadhramaut, arrived in <strong>the</strong> Malay<br />

Archipelago. Picken (1975:269) mentioned gambus in his book, Folk Musical Instruments<br />

from Turkey, in which he states: “<strong>The</strong> name gambus (from Indonesia [alam melayu] <strong>and</strong><br />

gabbus (Zanzibar), applied to structurally related lutes resembling <strong>the</strong> rebab <strong>of</strong> North-west<br />

Africa, are forms <strong>of</strong> kopuz – as Sachs recognized. …..<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> disappearance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> name<br />

kopuz from central regions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Islamic world, indicate that transmission to Zanzibar <strong>and</strong><br />

Madagascar, as well as to Indonesia (Borneo), probably occurred at an early date”.<br />

A <strong>Persian</strong> colony on <strong>the</strong> Malay Peninsula during <strong>the</strong> 5 th <strong>and</strong> 6 th centuries is reported<br />

by Chinese sources. Heuken (2002:13-29) mentions that 500 hundred <strong>Persian</strong> families lived<br />

during <strong>the</strong> 4 th century in Tun-sun on <strong>the</strong> Malayan Peninsula. Gujarati (in India) <strong>and</strong> <strong>Persian</strong><br />

merchants created a wide network <strong>of</strong> trading posts entirely controlled by Muslim Melaka in<br />

1414, Java <strong>and</strong> as far as Ternate (“spice” isl<strong>and</strong>) in <strong>the</strong> late 1460 A.D.<br />

Mohd. Anis has attributed <strong>the</strong> arrival <strong>of</strong> gambus to <strong>the</strong> Arabs during <strong>the</strong> Islamization<br />

<strong>of</strong> Melaka in <strong>the</strong> 15 th century. <strong>The</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>sis that I am suggesting for <strong>the</strong> transmission <strong>of</strong><br />

gambus to <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago could be even much earlier than <strong>the</strong> 15 th century. I am<br />

propounding that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Persian</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Arabs were trading in <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago as early<br />

as <strong>the</strong> 9 th century <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>se instruments could have been carried on board <strong>the</strong>ir ships for<br />

personal entertainment on long voyages. <strong>The</strong> barbat, qanbus <strong>and</strong> ūd could have been<br />

introduced by <strong>the</strong>se traders when trading along <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago. 13<br />

13 To assume <strong>the</strong> claim made by Sachs that <strong>the</strong> instruments may have been introduced into <strong>the</strong> Malay<br />

Archipelago as early as <strong>the</strong> 7 th century lacks convincing historical evidence <strong>and</strong> this claim is too far-fetched<br />

(1940). However <strong>the</strong>re are tangible historiograhical sources sighting Arab/<strong>Persian</strong> trading activities to support my<br />

hypo<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>of</strong> a later arrival [see Andaya <strong>and</strong> Andaya (1982); Alatas (1985); Mohad. Taib Osman (1988); Hourani<br />

6

<strong>The</strong> arrival <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gambus-type instruments into <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago may not<br />

imply that <strong>the</strong> acceptance <strong>and</strong> indigenization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> instruments was immediate but ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

happened through a gradual process <strong>of</strong> adaptation. <strong>The</strong>se instruments may have been used<br />

only by <strong>Persian</strong> <strong>and</strong> Arab traders based in <strong>the</strong> Malay trading ports. It was probably after <strong>the</strong><br />

Islamization <strong>of</strong> Melaka (Fig. 2, Stage 2) that <strong>the</strong> gambus was more fully integrated into <strong>the</strong><br />

region, especially after <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malay World became Islamized. My schematic map in<br />

Fig. 2 provides a diagrammatic illustration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>tical historical routes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gambus<br />

to alam melayu.<br />

(1995); <strong>and</strong> Hueken (2002)]. With those historical records, I am more convinced <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 9 th century arrival <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se<br />

instruments ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> 7 th century.<br />

7

Fig.2<br />

A Historical Hypo<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Arrival, Development <strong>and</strong> Dissemination <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> lutetype<br />

Instruments in alam melayu (<strong>the</strong> Malay World) from <strong>the</strong> 9 th to <strong>the</strong> 20 th century<br />

8

Alatas supports <strong>the</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>sis that <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> large <strong>Persian</strong> <strong>and</strong> Arab trading<br />

Muslim settlements in <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago. 14 He states that a thriving port also existed on<br />

<strong>the</strong> west coast <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malay Peninsular in <strong>the</strong> 9 th century (named Kalah or Klang) inhabited<br />

by Muslims from Persia <strong>and</strong> India. Kalah is in <strong>the</strong> State <strong>of</strong> Selangor where <strong>the</strong> capital Kuala<br />

Lumpur is situated. 15 It is not unreasonable to suggest that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Persian</strong>s brought <strong>the</strong> barbat to<br />

<strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago. <strong>The</strong> question that comes to mind is whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> gambus-type<br />

instruments come from Persia or <strong>the</strong> Arabian Peninsula? <strong>The</strong> gambus Melayu that came to<br />

<strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago could be ei<strong>the</strong>r a direct descendant <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> barbat or from <strong>the</strong><br />

Yemeni “qanbus”, which itself may have evolved from <strong>the</strong> “barbat”. 16<br />

<strong>The</strong> gambus Melayu has striking resemblances to both barbat <strong>and</strong> qanbus-type<br />

instruments in its physical structures. <strong>The</strong>re is historical evidence to suggest that ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se routes from Persia <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Arabian Peninsula were possible. <strong>The</strong> similarities between<br />

<strong>the</strong> gambus <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> barbat are those that also link <strong>the</strong> gambus with <strong>the</strong> qanbus. 17 Even <strong>the</strong><br />

14 Summary <strong>of</strong> papers on “<strong>Hadhrami</strong> Diaspora” were discussions in <strong>the</strong> conference at al-Wehdah (<strong>The</strong> Arab<br />

Association <strong>of</strong> Singapore) on <strong>the</strong> 20th August 1995. Speakers were: Dr. Farid Alatas, Alwiyah Abdul Aziz,<br />

Harasha bte. Khalid Banafa <strong>and</strong> Heikel bin Khalid Banafa. Also see Muslim World 75 nos.3-4, (Alatas: 1985:163).<br />

15 Alatas mentions in an article, “Notes on Various <strong>The</strong>ories Regarding <strong>the</strong> Islamization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago”<br />

that <strong>the</strong> Arab historians <strong>and</strong> geographers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 9th century knew <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> existence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Srivijaya Empire<br />

(Indonesia) which included large parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago. Ya’quibi, for example writes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> trading<br />

connections between Kalah on <strong>the</strong> west coast <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malay Peninsula <strong>and</strong> Aden (Yemen). Ano<strong>the</strong>r writer, Ibn al-<br />

Faqih (902) mentioned <strong>the</strong> cosmopolitanism <strong>of</strong> Kalah. Abu Zayd <strong>of</strong> Siraf (d.916) said Kalah lay half-way between<br />

China <strong>and</strong> Arabia <strong>and</strong> mentioned Kalah as a prosperous town inhabited by Muslims from India <strong>and</strong> Persia.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r 10th century source by Ismail b. Hasan mentioned this region in a condensed nautical treatise, as a work<br />

based in part on travels in <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago (Muslim World 75: nos: 3-4: 1985:163-4). However, historians<br />

Andaya <strong>and</strong> Andaya describe <strong>the</strong> Muslim trading colony <strong>of</strong> Kalah as being in <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malay<br />

peninsular (1982:51). Kalah Bar, probably at <strong>the</strong> modern Kedah State (north) <strong>of</strong> Peninsula Malaysia <strong>and</strong> Tiuman<br />

(Pulau Tioman – east side <strong>of</strong> Peninsula Malaysia) became important ports in <strong>the</strong> 10th century for Arab traders<br />

(Hourani: 1995:71). Heuken mentions that during <strong>the</strong> 9th century Kalah (known to <strong>the</strong> Chinese as Ko-lo) became<br />

important to <strong>the</strong> Arab seafarers, who, toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> <strong>Persian</strong>s traded <strong>the</strong>re with Chinese <strong>and</strong> Malay merchants<br />

as described by Ibn Khurdadhbih (2002:13). All <strong>the</strong>se facts support <strong>the</strong> evidence <strong>of</strong> Muslims from Persia, Arabia<br />

<strong>and</strong> India, inhabiting some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> important ports in <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago since <strong>the</strong> 9th century. Hence, this<br />

far<strong>the</strong>r supports <strong>the</strong> likelihood <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 9 th century dissemination <strong>of</strong> gambus lute-type instruments to this region.<br />

16 Shiloah mentions in his writing that <strong>the</strong> ūd was invented by a <strong>Persian</strong> philosopher Ibn Hidjdja (b.1366-d.1434)<br />

who called it a barbat (1979:180).<br />

17 <strong>The</strong> description given by Jean During in <strong>The</strong> New Grove Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Musical Instruments closely identifies <strong>the</strong><br />

barbat with <strong>the</strong> gambus Melayu. However, During did not say where <strong>the</strong> barbat came from but he did say: “<strong>The</strong><br />

barbat had four silk strings, sometimes doubled, tuned in 4ths <strong>and</strong> plucked with a plectrum…at an early date it<br />

9

strings <strong>of</strong> both types <strong>of</strong> gambus instruments are tuned in perfect 4ths, as is <strong>the</strong> case with most<br />

<strong>Persian</strong> <strong>and</strong> Arabian lutes. 18<br />

Plate (iv) Yemeni Qanbus Player 19<br />

Information ga<strong>the</strong>red about <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gambus Melayu is similar in manner<br />

to <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> barbat. Ella Zonis (1973:179-180) in her book Classical <strong>Persian</strong><br />

Music concludes that <strong>the</strong> barbat was constructed from one piece <strong>of</strong> wood, in contrast to <strong>the</strong><br />

Arab ūd, where <strong>the</strong> body <strong>and</strong> neck were separate. This confirms <strong>the</strong> close similarities<br />

apparent in <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> barbat <strong>and</strong> gambus Melayu.<br />

Plate (v) Qanbus Making 20<br />

was exported to Arabia via Ai-Hira on <strong>the</strong> Ephrates. <strong>The</strong> North African kwitra <strong>and</strong> Arab ūd can be considered<br />

descendants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> barbat as can <strong>the</strong> Chinese pipa <strong>and</strong> Japanese biwa” (1984: No.1: 156).<br />

18 Jean Lambert described in his book La médecine de l’âme that <strong>the</strong> qanbus from Yemen has three doublecourse<br />

strings tuned progressively in 4ths except for <strong>the</strong> low single string which is tuned an octave lower to <strong>the</strong><br />

high double-course strings (1997:90). <strong>The</strong> tuning in 4ths is similar to most gambus <strong>of</strong> alam melayu.<br />

19 Photograph is courtesy <strong>of</strong> Mr. Rafiq al-Akuri.<br />

10

One cannot doubt <strong>the</strong> possibility <strong>of</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> influence in <strong>the</strong> construction method <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

gambus Melayu. <strong>The</strong> descriptions by Sachs <strong>and</strong> Zonis about <strong>the</strong> gambus imply <strong>the</strong> instrument<br />

may be <strong>of</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> origin. Also, according to Farmer, <strong>the</strong> barbat was exported to <strong>the</strong> Arabian<br />

Peninsula from Persia. This may explain <strong>the</strong> close similarities between <strong>the</strong> ūd <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> qanbus<br />

from Yemen. Farmer (1967:108) concludes that <strong>Persian</strong> lutes were taken to Arabia in <strong>the</strong> late<br />

7 th century by <strong>Persian</strong> slaves who were to work in Mecca <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Arabian<br />

Peninsula. 21 In <strong>the</strong> 8 th century Zalzal introduced a new type <strong>of</strong> ūd which superseded <strong>the</strong><br />

barbat. It was this new invention (ūd) that was brought to Europe by <strong>the</strong> Arab invasion <strong>of</strong><br />

Spain <strong>and</strong> became known to <strong>the</strong> West as <strong>the</strong> lute. 22<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Impact</strong> <strong>of</strong> Islamisation on <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago<br />

Without doubt <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> Islamization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago played a crucial<br />

role in <strong>the</strong> transmission <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> lute-type instruments <strong>and</strong> Arab culture. S.Q. Fatimi<br />

has suggested that Islam arrived in <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago in four stages. First, early contacts<br />

from 674 A.D., second, Islam obtained a foothold in coastal towns around 878 A.D., third,<br />

Islam began achieving political power in 1204 A.D. <strong>and</strong> finally <strong>the</strong> decline set in from 1511<br />

A.D (69-70). It is difficult to state categorically when <strong>and</strong> how <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> lute-type<br />

instruments arrived in alam melayu. With little or no information regarding <strong>the</strong> specific<br />

arrival <strong>of</strong> gambus-type instruments, <strong>the</strong> present research relied heavily on historical accounts<br />

20 I am grateful to Mr. Samir Mokrani for this photograph.<br />

21 By <strong>the</strong> 5th century, <strong>the</strong> barbat was used by Byzantine <strong>and</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> singing girls. <strong>The</strong> Arabic ūd appeared in<br />

Mecca in <strong>the</strong> 6th century (Marcuse: 1975: 413).<br />

22 Farmer (1931a) concludes that <strong>the</strong> old pear-shaped barbat type lute, without a definite neck continued to exist<br />

side by side with <strong>the</strong> ūd in <strong>the</strong> Castigas de Santa Maria (<strong>The</strong> Origin <strong>of</strong> Arabian Lute <strong>and</strong> Rebec: p.98). Sachs also<br />

describes how a type <strong>of</strong> Moorish guitar <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 14th century ‘la guitarra morisca’ used by <strong>the</strong> Spaniards was more<br />

<strong>and</strong> more influenced by <strong>the</strong> lute today which descended from <strong>the</strong> ūd (1940:252).<br />

11

<strong>and</strong> on <strong>the</strong>ories regarding <strong>the</strong> Islamization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago during <strong>the</strong> 15 th<br />

century. 23 Early historical accounts <strong>of</strong> Islamization are vital clues for underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>the</strong><br />

dissemination <strong>of</strong> Arabian <strong>and</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> lute-type instruments in <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago.<br />

<strong>The</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>sis about <strong>the</strong> arrival <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> lute-type instruments<br />

through <strong>the</strong> Arabs <strong>and</strong> <strong>Persian</strong>s to <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago is a strong possibility since<br />

economic growth <strong>and</strong> political stability could have influenced cultural adaptation <strong>and</strong><br />

behaviour from a more dominant <strong>and</strong> influential cultural group (<strong>the</strong> Arabs). 24 <strong>The</strong>re is<br />

evidence to show that <strong>the</strong> early Arabs, who came to alam melayu to trade <strong>and</strong> settle down,<br />

were from Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Yemen (Alatas:1985;1997). Today <strong>the</strong> Arab community in Indonesia,<br />

Malaysia <strong>and</strong> Singapore is solely made up <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> Arabs <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> gambus, zapin <strong>and</strong><br />

sharah are closely associated with <strong>the</strong>m. <strong>The</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong>s could account for <strong>the</strong><br />

arrival <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> arched-back ūd (gambus Hadhramaut) <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Yemeni qanbus. 25<br />

Plate (vi) Yemeni musicians at a Wedding 26<br />

23 Hall D.G.E. (1970); Johns, A.H. (1981); Wolters (1982); Andaya <strong>and</strong> Andaya (1982); Alatas (1985); Reid<br />

(1993;2000); Tarling (1992) <strong>and</strong> Heuken (2002).<br />

24 Personal communication: Dr. Farid Alatas: 26th July 1999.<br />

25 Farmer mentions that <strong>the</strong> people from Al-Yaman (Yemen) had an instrument called qanbus which is also<br />

referred to as qabus could be traced back to <strong>the</strong> pre-Islamic time (1931:73).<br />

26 Photograph courtesy <strong>of</strong> P. Bonnenfant<br />

12

Even today music plays a significant part in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> community in zapin<br />

performances. 27 Performances <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gambus, zapin <strong>and</strong> sharah music <strong>and</strong> dance are<br />

significant at weddings, circumcisions <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r cultural <strong>and</strong> religious festivals in <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Hadhrami</strong> community. 28 Farmer also mentions that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong>s were not only traders, but<br />

great patrons <strong>of</strong> music. He concludes: “…real Arabian music comes from Al-Yaman,<br />

[Yemen], whilst <strong>the</strong> Hadrami minstrels are always considered to be superior artistes”<br />

(1967:3). 29 This supports <strong>the</strong> point that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> traders brought along <strong>the</strong>ir musical<br />

instruments when <strong>the</strong>y came to <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago to trade <strong>and</strong> settle. Ano<strong>the</strong>r fact that<br />

supports this view comes from many <strong>of</strong> my fieldwork observations that gambus players in<br />

samra performances were usually <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> descent, now settled in alam melayu. 30 My<br />

observation during my research was that many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> Arabs were more highly<br />

accomplished musicians than Malay performers. <strong>The</strong> arrival <strong>of</strong> Arabs from Hadhramaut is a<br />

vital link as it could explain <strong>the</strong> transmission <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> lute-type instruments to alam<br />

melayu, probably brought by <strong>the</strong>se traders <strong>and</strong> religious men from Yemen.<br />

27 Jean Lambert in a letter to me mentioned that zafin (zapin) is a kind <strong>of</strong> dance known to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong>s <strong>and</strong> Gulf<br />

Arabs. Zafin may have a qanbus in <strong>the</strong> musical performance. It is more an aristocratic musical art form (letter<br />

dated: 27th December 1999).<br />

28 On a number <strong>of</strong> occasions I have witnessed <strong>the</strong> performance <strong>of</strong> zapin music <strong>and</strong> dance held within <strong>the</strong> Arab<br />

(<strong>Hadhrami</strong>) community in Singapore. <strong>The</strong>se evening musical performances are called “samra”. <strong>The</strong> gambus<br />

plays <strong>the</strong> main role in <strong>the</strong> zapin performance in samra evenings. An interesting observation made at <strong>the</strong>se<br />

performances was that <strong>the</strong> musicians who were engaged to perform in <strong>the</strong> samra were from Indonesia. Most <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> musicians were <strong>of</strong> Arab (<strong>Hadhrami</strong>) descent. <strong>The</strong>y were very accomplished musicians who not only played<br />

Arabic tunes but also lagu-lagu Melayu (songs) <strong>and</strong> tunes from popular Hindustani film music. Loopuyt mentions<br />

that “morisco” (Moors), referring to <strong>the</strong> Spanish Muslims who were forced to convert to Christianity, continued <strong>the</strong><br />

tradition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> night musical sessions called “zambras”. <strong>The</strong>re seems to be some connection with <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong><br />

musical evenings called “samra” <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Andalusian’s “zambras” (personal communication: July 1999: France).<br />

29 Aghani, iv, 37 as quoted in <strong>the</strong> History <strong>of</strong> Arabian Music (Farmer: 1967). “Kitab al-Aghani” (Book <strong>of</strong> Songs) was<br />

written by Abu al-Faraj al-Isbahani who lived from 897-967 A.D. (Shiloah: 1997).<br />

30 <strong>The</strong> Malays use <strong>the</strong> word “samra” or “sharah” to refer to zapin Arab (zapin <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Arabs). Sharah dance form is<br />

not a zapin but it is usually danced by male performers as an individual solo dance or in pairs. Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Shiloah<br />

pointed out to me <strong>the</strong> word “samra” or “zambras” derives from <strong>the</strong> Arabic samar or musamara, which means<br />

nocturnal conversation <strong>and</strong> depicts a “literary” genre. He also mentioned <strong>the</strong> word “samra” used in Yemen,<br />

designating a nocturnal entertainment session which includes singing, dances <strong>and</strong> music-making (personal<br />

communication: July 1999: France).<br />

13

<strong>The</strong> Significance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 19 th Century <strong>Hadhrami</strong> Arrival<br />

In <strong>the</strong> 19 th century <strong>the</strong>re was a greater interest shown by <strong>the</strong> Arabs in trading with <strong>the</strong><br />

Malay world, <strong>and</strong> some Arabs settled down in <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago. 31 <strong>The</strong> Arab<br />

immigrants in Indonesia, Singapore <strong>and</strong> Malaysia originated predominantly from <strong>the</strong> valley<br />

<strong>of</strong> Hadhramaut (Yemen). In <strong>the</strong> 19 th century <strong>Hadhrami</strong> Arabs played a significant role in <strong>the</strong><br />

spread <strong>of</strong> Islam as well as commercial trade in Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Asia. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> not only<br />

arrived in Malaysia, as traders <strong>and</strong> merchants, but many were cultured <strong>and</strong> scholarly men<br />

imbued in Arabic literature, religious law <strong>and</strong> philosophy. <strong>The</strong>y traded extensively in <strong>the</strong><br />

archipelago where <strong>the</strong>y were granted special commercial privileges because <strong>the</strong>y were <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

same “race” as <strong>the</strong> Prophet. 32 By <strong>the</strong> 19 th century, it had become <strong>the</strong> spread <strong>of</strong> Islam that was<br />

<strong>the</strong> primary goal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Arabs in alam melayu. <strong>The</strong> Arabs brought along not only trade but<br />

rich cultural traditions.<br />

In fact, musical instruments such as <strong>the</strong> arched-back ūd arrived in this region in <strong>the</strong> 19 th<br />

century <strong>and</strong> became <strong>the</strong> predominant form <strong>of</strong> gambus in Peninsular Malaysia. Interestingly,<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> communities in alam melayu provide a fascinating case <strong>of</strong> transnational<br />

communities. <strong>The</strong>y assimilated well into <strong>the</strong>ir host countries <strong>of</strong> Indonesia, Malaysia <strong>and</strong><br />

Singapore but retained <strong>the</strong>ir cultural identity at <strong>the</strong> same time. This is referred to as <strong>the</strong><br />

Hadhami practice <strong>of</strong> asabiyya. 33<br />

31 <strong>The</strong> 19th century events in <strong>the</strong> Malay world were significant because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> : (1) large influx <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong><br />

emigration “diaspora” (Alatas: 1997); (2) <strong>the</strong> opening <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Suez Canal in 1869 <strong>and</strong> shorten sea journey; (3) <strong>the</strong><br />

increase <strong>Hadhrami</strong> trade with <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago <strong>and</strong> (4) <strong>the</strong> new arrival <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Islamic mullahs <strong>and</strong> religious<br />

scholars (ulamas) from Hadhramaut to this region.<br />

32 “Race” is a biological term which is sometimes confused with ethnicity. <strong>The</strong> term race is scientifically flawed<br />

when used to define categories such as Chinese, Malays, Indians, etc. It is a biological term to identify with racial<br />

categories such as Mongoloid, Caucasoid <strong>and</strong> Negroid. Even more important is <strong>the</strong> social <strong>and</strong> cultural factors<br />

that imply one’s membership to a particular ethnic group <strong>and</strong> not just <strong>the</strong> racial outlook, colour <strong>of</strong> hair or skin. It is<br />

a term sometimes exploited for political reasons. However, <strong>the</strong> deeper definition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> term “race” is not within<br />

<strong>the</strong> discussion <strong>of</strong> this research.<br />

14

<strong>The</strong> evidence <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> cultural links is still strong today in Gresik, Surabaya <strong>and</strong><br />

Jakarta in Java <strong>and</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong>s still live in eastern Sumatra in places such as Melayu, Siak,<br />

Padang, Medan, Jambi, Bukit Si Gunung, Siak, Palembang, <strong>and</strong> Aceh. 34 In Singapore <strong>and</strong><br />

Malaysia <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> community, although having adopted some Malay cultural practices,<br />

has not integrated fully with <strong>the</strong> Malay grouping <strong>and</strong> still prefers to be identified as Arab.<br />

<strong>The</strong> differences between <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> <strong>and</strong> Malay communities in music <strong>and</strong> dance are<br />

apparent from <strong>the</strong> interpretation <strong>of</strong> performances <strong>of</strong> zapin (as in zapin Arab or zapin Melayu).<br />

One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most important cultural contributions from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong>s is definitely in<br />

zapin music <strong>and</strong> dance <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> gambus <strong>and</strong> marwas in Malay music. Evidently, <strong>the</strong><br />

Malays have adopted many o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Hadhrami</strong> influences into <strong>the</strong>ir culture. <strong>The</strong> word Rabu<br />

(Wednesday), <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> reciting style <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Qur’an, <strong>the</strong> thuluth script, <strong>the</strong> language <strong>and</strong><br />

knowledge <strong>of</strong> Islam (ilmu) <strong>and</strong> many aspects <strong>of</strong> custom can be traced to that <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong><br />

influences. <strong>The</strong> word adat was also adopted from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> Shafii sect <strong>of</strong> Sunni Islam.<br />

<strong>The</strong> practice <strong>of</strong> death ritual (tahlil), <strong>the</strong> male dress (gamis or tob) <strong>and</strong> Muslim names such as<br />

Ali, Hussein, Omar, Ahmad, Mohamad, Abdullah <strong>and</strong> Ismail are all <strong>Hadhrami</strong> practises. 35<br />

<strong>The</strong> re-introduction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Arched-back <strong>Hadhrami</strong> Gambus<br />

33 Alatas describes this as <strong>Hadhrami</strong> consciousness <strong>and</strong> identity. He pointed out that for centuries, “<strong>Hadhrami</strong>s<br />

married into Malay-Indonesian communities <strong>and</strong> retained <strong>the</strong>ir cultural identities without losing <strong>the</strong>ir sense <strong>of</strong><br />

Hadhami identity because such identity is not national or ethnic but kinship-based” (personal communication:<br />

12th July 1999). Also see Alatas (1996:10).<br />

34 Inhabitants <strong>of</strong> Arab origin can nowadays be found in all Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Asian countries, with <strong>the</strong> exception <strong>of</strong> Laos<br />

(Bajouned 1996). <strong>The</strong> vast majority, however, live in Indonesia, Malaysia <strong>and</strong> Singapore (Jonge <strong>and</strong> Kaptein eds.<br />

2002). However, <strong>the</strong>re are also <strong>Hadhrami</strong> Arabs living in <strong>the</strong> Malay World who do not display any distinctive Arab<br />

cultural attributes, while o<strong>the</strong>rs identify <strong>the</strong>mselves as Arabs first, <strong>the</strong>n Malays. It seems that <strong>the</strong> more recent<br />

migrants identify <strong>the</strong>mselves more as <strong>Hadhrami</strong>s <strong>and</strong> less as Malays. Some <strong>Hadhrami</strong> Arabs also prefer to<br />

identify <strong>the</strong>mselves as Malays because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> privileges <strong>the</strong>y get as Bumiputeras in Malaysia.<br />

35 Interview on <strong>Hadhrami</strong> culture <strong>and</strong> music was conducted with an influential <strong>Hadhrami</strong> community elder, Syed<br />

Ali Alattas from Johor Bahru on <strong>the</strong> 27th June 2000. However, it has also been pointed out to me that all <strong>the</strong> Arab<br />

names mentioned above are not necessarily Muslim names as <strong>the</strong>y are also used by Christian Arabs in <strong>the</strong><br />

Middle-East.<br />

15

Having considered <strong>the</strong> various “<strong>the</strong>ories” on <strong>the</strong> arrival <strong>and</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Hadhrami</strong> lute-type instruments, <strong>the</strong>re is one more hypo<strong>the</strong>sis on <strong>the</strong> arrival <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> arched-<br />

back ūd in particular. <strong>The</strong> opening <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Suez Canal in 1869 would have shortened <strong>and</strong> sped<br />

up <strong>the</strong> sea journey from <strong>the</strong> Middle-East to alam melayu. With <strong>the</strong> impetus <strong>of</strong> steam<br />

navigation <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> opening <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Suez Canal <strong>the</strong> economic prospects for <strong>the</strong> Malay<br />

peninsular was good (Shennan: 2000: 6). <strong>The</strong> Arabian ūd, but this time coming from o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Middle-East, could have been re-introduced as a “second coming” <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gambus<br />

in alam melayu. It can be argued that <strong>the</strong> popularity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ūd (gambus Hadhramaut)<br />

superseded that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> skin-bellied gambus Melayu in <strong>the</strong> late 19 th or early 20 th century in<br />

Peninsular Malaysia. 36 <strong>The</strong> ghazal groups <strong>of</strong> Johor in <strong>the</strong> early 20 th century were replacing<br />

Indian sarangi with <strong>the</strong> gambus Melayu <strong>and</strong> later by <strong>the</strong> gambus Hadharamaut. In Peninsular<br />

Malaysia today, <strong>the</strong> gambus Melayu has been almost completely replaced by <strong>the</strong> gambus<br />

Hadhramaut.<br />

Plate (vii) Lute Maker in Yemen 37<br />

36 This view about <strong>the</strong> popularity <strong>of</strong> ūd replacing <strong>the</strong> gambus Melayu in <strong>the</strong> late 19th century is also shared by<br />

most Malay music scholars. <strong>The</strong> late Pak Fadzil Ahmad, a distinguished performer attached to <strong>the</strong> Ministry <strong>of</strong><br />

Culture, claims that <strong>the</strong> ūd, became more popular in around 1897 in Johor, replacing <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> gambus<br />

Melayu. Although some Malay musicians disagree <strong>and</strong> mention that <strong>the</strong> ūd was only introduced in <strong>the</strong> 1950’s.<br />

37 Photograph courtesy <strong>of</strong> Toni Ferghali.<br />

16

As both <strong>the</strong> gambus Melayu <strong>and</strong> gambus Hadhramaut may have come from <strong>the</strong> same<br />

genealogical development, it seems that no distinction was necessary between <strong>the</strong> two types<br />

<strong>of</strong> instrument but <strong>the</strong> generic term “gambus” was used to refer to both types <strong>of</strong> instruments<br />

by <strong>the</strong> Malays. Ano<strong>the</strong>r important fact explaining <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> any kind <strong>of</strong> differentiation is<br />

that both types <strong>of</strong> gambus are used interchangeably in <strong>the</strong> performance <strong>of</strong> Malay musical<br />

genres such as zapin, hamdolok, asli, inang, masri, <strong>and</strong> ghazal. Both types <strong>of</strong> gambus are<br />

found in Sarawak <strong>and</strong> Sabah in East Malaysia <strong>and</strong> also in Brunei <strong>and</strong> west Kalimantan<br />

(Borneo) in Indonesia.<br />

Conclusion<br />

Some Malays strongly believe that <strong>the</strong> gambus Melayu is <strong>of</strong> Malay origin, as opposed<br />

to <strong>the</strong> gambus Hadhramaut, which <strong>the</strong>y acknowledge to be <strong>of</strong> Middle-Eastern origin. <strong>The</strong><br />

arguments about <strong>the</strong> gambus Melayu <strong>the</strong>y have put forward as Malay origin are unconvincing<br />

<strong>and</strong> inconclusive, as <strong>the</strong>re was no proto-type or primitive forms <strong>of</strong> Malay lute found in <strong>the</strong><br />

Malay World. It is also unlikely from <strong>the</strong> evidence presented in this research shows that <strong>the</strong>se<br />

instruments were brought by <strong>Persian</strong> <strong>and</strong> Arab traders. <strong>The</strong> only examples <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gambus<br />

Melayu considered as modeled on <strong>the</strong> Arabian ūd are those found in Brunei, shown below in<br />

Plate (viii), with <strong>the</strong>ir wooden bellies, arched-back, <strong>and</strong> round sound holes.<br />

Plate (viii) Gambus Melayu<br />

(Brunei)<br />

17

An instrument <strong>of</strong> this kind has also been found in Sulawesi but it has 6 double-strung<br />

strings. A specimen <strong>of</strong> this type <strong>of</strong> gambus from Sulawesi, shown in Plate (ix), was also<br />

found in <strong>the</strong> Musée de l’Homme in France. 38<br />

Plate (ix) Gambusu<br />

Musée de l’Homme (France)<br />

Evidence pointing towards <strong>the</strong> contribution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Muslims from Persia <strong>and</strong> Arabia in<br />

<strong>the</strong> transmission <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong>/<strong>Persian</strong> lute-type instruments to <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago is<br />

substantial <strong>and</strong> conclusive. <strong>The</strong> use <strong>of</strong> terms such as: Hadhramaut, Yemen, gambus, zapin,<br />

sharah, samra, marwas, Arab, <strong>and</strong> Hijaz, could be plausible admission <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong><br />

influences <strong>and</strong> transmission <strong>of</strong> lute instruments from Yemen ra<strong>the</strong>r than Persia. 39 With <strong>the</strong><br />

Islamization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago in <strong>the</strong> 15th century, many Muslim Arab traders<br />

established strong trade links with <strong>the</strong>se areas. However, I have not come across <strong>the</strong> word<br />

“qanbus” in any primary text, although <strong>the</strong> word “barbat” has been used frequently to<br />

describe <strong>the</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> lute. <strong>The</strong>re is also concrete historical evidence that supports <strong>the</strong> presence<br />

38 I am grateful to Lucie Rault at Musée de l’Homme (France) who made all <strong>the</strong> necessary arrangements for me<br />

to make a detailed study <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> instrument. This instrument was labelled as “gambusu” from Sulawesi, in<br />

Indonesia.<br />

18

<strong>of</strong> “Parsi” (<strong>Persian</strong>) influence in alam melayu. However, whe<strong>the</strong>r it was direct or indirect,<br />

<strong>Persian</strong> influence on Malay culture has been particularly strong, especially on <strong>the</strong> Malay<br />

royal courts. Thus, <strong>the</strong> argument that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> lute come to alam melayu cannot be<br />

dismissed altoge<strong>the</strong>r. 40<br />

My argument points to <strong>the</strong> fact that both types <strong>of</strong> gambus were already highly<br />

developed when introduced into <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago. <strong>The</strong>re is no evidence <strong>of</strong> “similar” or<br />

“primitive” types <strong>of</strong> lute found that could point to <strong>the</strong> gambus being indigenous to alam<br />

melayu. 41 <strong>The</strong> gambus may have developed over <strong>the</strong> centuries in alam melayu. However, <strong>the</strong><br />

striking resemblance to qanbus or barbat supports <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory that it was an “imported”<br />

instrument ra<strong>the</strong>r than being indigenous to alam melayu, albeit now modified <strong>and</strong> adapted.<br />

Plate (x) is a photograph <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> qanbus from Yemen. 42<br />

39 See Poche (1984) <strong>and</strong> Kunst (1952/1994).<br />

Plate (x) Qanbus (Yemen)<br />

40 Mohd. Taib Osman mentions <strong>the</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> influence on <strong>the</strong> culture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malays has been<br />

particularly strong especially on <strong>the</strong> Malay royal courts. Malay court ceremonies, <strong>the</strong> title “Shah” for<br />

<strong>the</strong> sultans or rulers, literature <strong>and</strong> ideas on statescraft <strong>and</strong> kingship, <strong>the</strong> literary style <strong>of</strong> court<br />

literature, <strong>and</strong> religious literature <strong>of</strong> Shi’ite tradition, all bear indelible marks <strong>of</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> influence<br />

(1988: 267). Also refer to G.E. Marrison, “<strong>Persian</strong> Influences on Malay Life”, Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malayan<br />

Branch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Royal Asiatic Society, XXVIII (1955:80). G.W.J. Drewes comments that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Persian</strong><br />

influence seems to exist alongside <strong>the</strong> Arabian influences in <strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago in an article “New<br />

Light on <strong>the</strong> Coming <strong>of</strong> Islam to Indonesia” (1985:7-9).<br />

41 <strong>The</strong> musicians <strong>and</strong> scholars I spoke to in Indonesia, (S.Berrain), Malaysia, (Pr<strong>of</strong>essor. Mohd. Anis)<br />

<strong>and</strong> Brunei, (Haji Nayan bin Apong) seem to agree that <strong>the</strong> gambus Melayu originated from alam<br />

melayu (Malay World).<br />

42 I am indebted to Dr. Nizar Ghanem <strong>and</strong> Dr. Jean Lambert for <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> this photograph.<br />

19

I am convinced from <strong>the</strong> arguments that <strong>the</strong> gambus Hadhramaut was a later arrival to<br />

alam melayu as <strong>the</strong> ūd only arrived in Yemen in <strong>the</strong> 19th century. 43 My research suggests that<br />

gambus Melayu type instruments probably arrived first. It could even be possible that <strong>the</strong>se<br />

pear-shaped skin-bellied lutes were transmitted by o<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>and</strong> not only <strong>the</strong> Arabs from<br />

Hadhramaut.<br />

References<br />

Alatas, S. Farid. (1985). Notes on Various <strong>The</strong>ories Regarding <strong>the</strong> Islamization <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Malay Archipelago. Muslim World, 75, No.3-4, 162-175.<br />

Alatas, S. Farid. (1997). Ulrike, F. & William G. Clarence-Smith. (Eds.).<br />

Hadhramaut <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hadhrami</strong> Diaspora: Problems in <strong>The</strong>oretical History.<br />

Hadrami Traders, scholars <strong>and</strong> Statesmen in <strong>the</strong> Indian Ocean, 1750’s1960s.<br />

Leiden-New York-Koln: Brill, 19-34.<br />

Andaya, B.W. & Andaya L.Y. (1982). A History <strong>of</strong> Malaysia. London: Macmillan<br />

Press Ltd.<br />

Bachmann, W.(1969). <strong>The</strong> Origins <strong>of</strong> Bowing. London: Oxford University Press.<br />

Baines, A. (1992).<strong>The</strong> Oxford Companion to Musical Instruments. Oxford<br />

University Press: UK.<br />

Beg, M.A.J. (1982). <strong>Persian</strong> <strong>and</strong> Turkish Loan-Words in Malay. University<br />

Kebangsaan Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: University <strong>of</strong> Malaya Press.<br />

Bouterse, C.(1979). Reconstructing <strong>the</strong> Medieval Arabic Lute: A Reconsideration <strong>of</strong><br />

Farmer’s ‘Structure <strong>of</strong> Arabian <strong>and</strong> <strong>Persian</strong> Lute. <strong>The</strong> Galpin Society Journal,XXXII<br />

(May), 2-76. Oxford University Press, UK.<br />

Brown, C.C. (1970). Sejarah Melayu: Malay Annals trans. (Reprint). Kuala Lumpur:<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Royal Asiatic Society (Malayan Branch), 25 parts, Nos.2 & 3.<br />

Capwell, C. (1995). Contemporary Manifestations <strong>of</strong> Yemeni-Derived Song <strong>and</strong><br />

Dance in Indonesia. Yearbook for Traditional Music, 76-89.<br />

43 This astonishing fact was confirmed to me in a letter by Dr. Jean Lambert on <strong>the</strong> 27th December 1999. Dr.<br />

Lambert is an authority on <strong>the</strong> music <strong>of</strong> Yemen. His work on <strong>the</strong> qanbus <strong>and</strong> ūd from Yemen is discussed in La<br />

médecine de l’âme. Le chant de Sana dans la société Yemenite. Nanterre, Société d’ ethnoligie,1997.<br />

20

Coope, A.E. (1991). Malay-English/English–Malay Dictionary (Revise Edition).<br />

Malaysia: Macmillan Publication.<br />

Cortesáo, A. (Ed.) (1990). <strong>The</strong> Suma Oriental <strong>of</strong> Tome Pires: An Account <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

East, from <strong>the</strong> Red Sea to Japan, Written in Malacca <strong>and</strong> India in 1512-1515 (Vol 1<br />

<strong>and</strong> 2). New Delhi: Asian Educational Services.<br />

Drewes, G.W.J. (1985). Reading on Islam in Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Asia. Compiled by Ahmad<br />

Ibrahim, Sharon Siddique <strong>and</strong> Yasmin Hussain. Singapore: Institute <strong>of</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>ast<br />

Asian Studies.<br />

Fatimi, S.Q.(1963). Shirle Gordon. (Ed). Islam Comes to Malaysia. Singapore:<br />

Malaysian Sociological Research Institute, Ltd.<br />

Farmer, H.G. (1931) [a] <strong>The</strong> Origin <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Arabian Lute <strong>and</strong> Rebec. Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Royal Asiatic Society, 91-107.<br />

Farmer, H.G. (1931) [b]. Meccan Musical Instruments. Studies in Oriental Musical<br />

Instruments, First Series. London: Harold Reeves, 71-87.<br />

Farmer, H.G. (1967). A History <strong>of</strong> Arabian Music. London: Luzac <strong>and</strong> Co Ltd.<br />

Gibb, H.A.R. (1999). <strong>The</strong> Travels <strong>of</strong> Ibn Battuta A.D. 1325–1354. New Delhi:<br />

Munshiram Manoh.<br />

Heuken, A. (2002). “Be my Witness to <strong>the</strong> Ends <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Earth!”. Yayasan Cipta Loka<br />

Caraka. Jakarta: Indonesia.<br />

Hilarian, L. F. (2003). Documentación y rastreo histórico del laúd malayo<br />

(gambus). Desacatos Revista de Antropologia Social. 12 Expresiones y sonidos de<br />

los pueblos (Mexico), 78-92.<br />

Hilarian, L. F. (2005). <strong>The</strong> Structure <strong>and</strong> Development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Gambus (Malay-<br />

Lutes). <strong>The</strong> Galpin Society Journal, LVIII, 66-82; 215-216. Oxford University<br />

Press, UK.<br />

Hilarian, L. F. (2009?). Is Kompang Compatible with Islamic Practices <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malay<br />

Muslim Society? Berlin Conference Papers, <strong>The</strong> Publishing House Munster,<br />

Munster M & V Wissenchsaft, Germany. (In-print).<br />

Stanley, S. (Ed). (1980). “VII Sumatra”. <strong>The</strong> New Grove Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Music <strong>and</strong><br />

Musicians. London: Macmillan, Vol.9, 215-216.<br />

Hornbostel, Erich M. von & Sachs, Curt. (1961). Classification <strong>of</strong> Musical<br />

Instruments. (A. Baines <strong>and</strong> K. Wachsmann, Trans.). Galpin Society Journal, 14:3-<br />

39. Oxford University Press: UK.<br />

Hourani, G. (1994). Arab Seafaring. Princeton University Press:USA.<br />

Ismail Haji, Abdul Rahman. (1998). Sejarah Melayu. <strong>The</strong> Malaysian Branch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

21

Royal Asiatic Society. Academe Arts <strong>and</strong> Printing Service Sdn. Bhd.<br />

Jong, de Huub & Kaptein, Nico (Eds.) (2002).Transcending Borders: Arabs,<br />

Politics, Trade <strong>and</strong> Islam in Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Asia. Leiden: KITLV Press<br />

Kunst, J. (1994). Indonesian Music <strong>and</strong> Dance. Traditional Music <strong>and</strong> its<br />

interaction with <strong>the</strong> West. A complilation <strong>of</strong> articles (1934-1952) originally<br />

published in Dutch, with biographical essays by Ernest Heins, Elisabeth den Otter<br />

<strong>and</strong> Felix van Lamsweerde. Royal Tropical Institute: University <strong>of</strong> Amsterdam :<br />

Holl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Lambert, J. (1997). La médecine de l’ậme Le chant de Sanaa dans la société<br />

yéménite. Hommes et Musiques. Société d’ethnologie. Paris: France.<br />

McAmis, R. D. (2002). Malay Muslims. Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing<br />

Co.<br />

Majul, Adib Cesar. (1973). Muslim in <strong>the</strong> Philippines. Diliman, Quezon City:<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Philippines Press.<br />

Marcuse, S. (1975). A Survey <strong>of</strong> Musical Instruments. David <strong>and</strong> Charles Limited:<br />

Great Britain.<br />

Marrison, G. E. (1955). <strong>Persian</strong> Influences on Malay Life, Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malayan<br />

Branch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Royal Asiatic Society, XXVIII, 80.<br />

Mohd. Anis Md. Nor. (1993). Zapin, Folk Dance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Malay World. Singapore:<br />

Oxford University Press.<br />

Mohd.Taib Osman. (Ed). (1974). Traditional Drama <strong>and</strong> Music <strong>of</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Asia.<br />

Dewan Bahasa Dan Pustaka Kementerian Pelajaran. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysia.<br />

Mohd.Taib Osman. (1988). Bunga Rampai: Aspect <strong>of</strong> Malay Culture. Dewan<br />

Bahasa dan Pustaka Kementerian Pendidikan. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysia.<br />

Nik Mustapha Nik M.S.(n.d.). Alat Muzik Tradisional Dalam Masyarakat, Melayu<br />

di Malaysia. Kementerian Kebudayaan, Kesenian Dan Pelancongan. Kuala Lumpur:<br />

Malaysia.<br />

Panum, H. (Ed.). (1971). Stringed Instruments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Middle Ages. Jeffrey Pulver,<br />

London:William Reeves.<br />

Picken, L. (1955). <strong>The</strong> Origin <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Short Neck Lute. Galpin Society Journal, VIII,<br />

32, 32-42<br />

Picken, L. (1975). Folk Musical Instruments <strong>of</strong> Turkey. London: Oxford University<br />

Press, UK.<br />

Poche, C. (1994). Musiques Du Monde Arabe, Ecoute et decouverte. Institut Du<br />

Monde Arabe. Paris: France.<br />

22

Aldo, Ricci. (2002). <strong>The</strong> Travels <strong>of</strong> Marco Polo. New Delhi: (Reprint) Rupa <strong>and</strong> Co.<br />

R<strong>of</strong>f, R. W. (2009). Studies on Islam <strong>and</strong> Society in Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Asia. NUS Press,<br />

Singapore.<br />

Sachs, C. (1913). Reallexikon der Musikinstrumente, Berlin: Nachdruck der<br />

Ausgabe.<br />

Sachs, C. (1940). <strong>The</strong> History <strong>of</strong> Musical Instruments. New York: W.W. Norton <strong>and</strong><br />

Company, Inc. Publishers.<br />

Shennan, M. (2000). Out in <strong>the</strong> Midday Sun (<strong>The</strong> British in Malaya 1880-1960).<br />

London: John Murray (Publishers) Ltd.<br />

Shiloah, A. (1979). <strong>The</strong>ory <strong>of</strong> Music in Arabic Writings c.900-1900. RISM (Edited).<br />

Muchen: G.Henle Verlag<br />

Shiloah, A. (1995). Music in <strong>the</strong> World <strong>of</strong> Islam. Detriot: Wayne State University<br />

Press.<br />

Stanley, Sadie (Ed.) (1980). <strong>The</strong> New Grove Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Music <strong>and</strong> Musicians.<br />

London: Macmillan Publishers Limited.<br />

Stanley, Sadie (Ed.) (1984). <strong>The</strong> New Grove Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Musical Instruments.<br />

London: Macmillan Publishers Limited.<br />

Stanley, Sadie (Ed.) (2001). <strong>The</strong> New Grove Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Music <strong>and</strong> Musicians:<br />

London: Macmillan Publishers Limited.<br />

Tarling, N. (Ed.) (1992). <strong>The</strong> Cambridge History <strong>of</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Asia, from Early<br />

Times to c. 1800. (Vols:1 <strong>and</strong> 2). Cambridge University Press.<br />

Van Leur, J.C. (1955). Indonesian Trade <strong>and</strong> Society. Sumur, B<strong>and</strong>ung. Indonesia.<br />

Winstedt, R.O. (1991). History <strong>of</strong> Malay Literature. Introduction by W.A. Talib,<br />

Malaysian Branch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Royal Asiatic Society Publication.<br />

Wolters O.W. (1982). History, Culture <strong>and</strong> Region in South East Asian<br />

Perspectives. Institute <strong>of</strong> South East Asian Studies Publication: Singapore.<br />

Zeus, A. S. (1998). <strong>The</strong> Malayan Connection, Ang Pilipinas sa Dunia Melayu.<br />

Palimbagan ng Lahi. Quezon: Philippines.<br />

Zonis, E. (1973). Classical <strong>Persian</strong> Music. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard<br />

University Press.<br />

23