OUSEION - Memorial University's Digital Archives Initiative ...

OUSEION - Memorial University's Digital Archives Initiative ...

OUSEION - Memorial University's Digital Archives Initiative ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

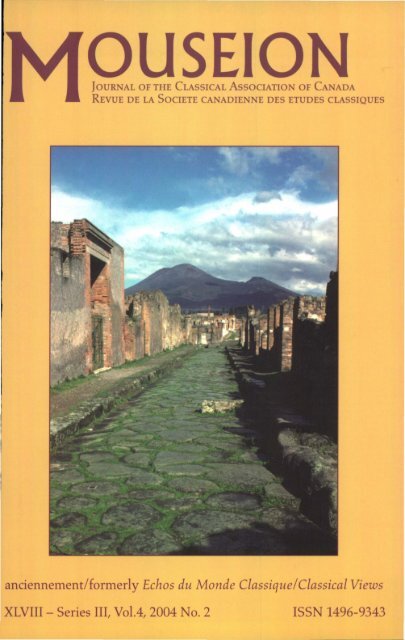

<strong>OUSEION</strong><br />

JOURNAL OF THE CLASSICAL ASSOCIATION OF CANADA<br />

REVUE DE LA SOCIETE CANADIENNE DES ETUDES CLASSIQUES<br />

anciennementlformerly Echos du Monde Classique/Classical Views<br />

XLVIII - Series III, VolA, 2004 No.2 ISSN 1496-9343

Mouseion (formerly Echos du Monde Classique/Classical Views) is publishcd by the<br />

University of Calgary Press for the Classical Association of Canada. Members of the<br />

Association receive both Mouseion and Phoenix. The journal appears three timcs per<br />

year and is available to those who are not members of the CAC at $25.00 Cdn./U.S. (individual)<br />

and $40.00 Cdn./U.S. (institutional). Residents of Canada must add 7% GST.<br />

ISSN: 1496-9343.<br />

MOl/seion (anciennement Echos du Monde Classique/Classical Views) est publie par les<br />

Presses de l'Universite de Calgary pour Ie compte de la Societe canadienne des etudes<br />

c1assiques. Les membres de cette societe reyoivent Mouseion et Phoenix. La revue parait<br />

trois fois par an. Les abonnements sont disponibles, pour ceux qui ne seraient pas IllCIllbres<br />

des SCEC, au prix de $25.00 Cdn./U.S., ou de $40.00 Cdn./U.S. pour les institutions.<br />

Les residents du Canada doivent payer la 7% TPA. ISSN: 1496-9343.<br />

Send subscriptions (payable to "Mouseion") to:<br />

Envoyer les abonnements (

M<strong>OUSEION</strong><br />

Journal of the Classical Association of Canada<br />

Revue de la Societe canadienne des etudes dassiques<br />

XLVIII - Series III, Vol. 4, 2004<br />

ARTICLES<br />

No.2<br />

Liz Warman. Hope in a Jar I07<br />

Eugenio Amato, Une nouvelle allusion aSimonide chez Chorikios<br />

de Gaza<br />

Jacqueline Clarke. "Goodbye to All That": Propertius'magnum iter<br />

between Elegies 3.16 and3.21 127<br />

Stephen Brunet, Female and DwarfGladiators 145<br />

Pascale Hummel. En qUt?te d'un reel1inguistique, ou 1a construction<br />

des 1angues anciennes par 1a tradition phi1010gique 171<br />

BOOK REVIEWS/COMPTES RENOUS<br />

Claude Calame, Myth and History in Ancient Greece: The Symbolic<br />

Creation ofa Colony. Translated by Daniel W. Berman (Noel<br />

Robertson) 191<br />

Samuel Shirley, trans., Herodotus: On the War for Greek Freedom.<br />

Selections from the Histories (Steven J. Willett) 194<br />

Gerard J. Pendrick, ed., Antiphon the Sophist: The Fragments<br />

(Brad Levett) 198<br />

Jenny March, ed., Sophocles: Electra: Leona MacLeod, Oolos and<br />

Dike in Sophokles' Elektra (Martin Cropp) 202<br />

Angela Hobbs, Plato and the Hero: Courage, Manliness and the<br />

Impersonal Good (John P. Harris) 207<br />

Ruby Blondell. The Play ofCharacter in Plato's Dialogues<br />

(Harold Tarrant) 212<br />

Malcolm K. Brown. The "Narratives" ofKonon. Text, Translation<br />

and Commentary of the Diegeseis (Rory B. Egan) 217<br />

Susan Treggiari. Roman Social History (Helene Leclerc) 224<br />

Roy K. Gibson, ed., Ovid. Ars Arnatoria, Book 3 (Peter E. Knox) 226<br />

S. Phillippo, Silent Witness: Racine's Non-Verbal Annotations of<br />

Euripides (Gerald Sandy) 229

Editorial Correspondents/Conseil consultatif: Janick Auberger. Universite<br />

du Quebec a Montreal: Patrick Baker. Universite Laval; Barbara<br />

Weiden Boyd. Bowdoin College; Robert Fowler. University of Bristol;<br />

John Geyssen. University of New Brunwsick; Mark Golden. University<br />

of Winnipeg; Paola Pinotti. Universita di Bologna; James Rives. York<br />

University; c.J. Simpson. Wilfrid Laurier University<br />

REMERCIEMENTS/ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

Pour l'aide financiere qU'ils ont accordee a la revue nous tenons a<br />

remercier / For their financial assistance we wish to thank:<br />

Conseil de recherches en sciences humaines du Canada / Social Sciences<br />

and Humanities Research Council of Canada<br />

Dean of Arts. <strong>Memorial</strong> University of Newfoundland<br />

Dean of Arts. University of Manitoba<br />

University of Manitoba Centre for Hellenic Civilization<br />

Brock University<br />

Dalhousie University<br />

University of New Brunswick<br />

University of Victoria<br />

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada.<br />

through the Publication Assistance Program (PAP). toward our mailing<br />

costs.<br />

No part of this publication may be reproduced. stored in a retrieval system or<br />

transmitted. in any form or by any means. without the prior written consent of<br />

the editors or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access<br />

Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence. visit www.accesscopyright.ca or<br />

call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Mouseion aims to be a distinctively comprehensive Canadian journal of<br />

Classical Studies. publishing articles and reviews in both French and<br />

English. One issue annually is normally devoted to archaeological topics.<br />

including field reports. finds analysis. and the history of art in antiquity.<br />

The other two issues welcome work in all areas of interest to<br />

scholars; this includes both traditional and innovative research in philology.<br />

history. philosophy. pedagogy. and reception studies. as well as<br />

original work in and translations into Greek and Latin.<br />

Mouseion se presente comme un periodique canadien d'etudes classiques<br />

polyvalent. publiant des articles et comptes rendus en fran

ABSTRACfS/RESUMES<br />

HOPE IN AJAR<br />

LIZ WARMAN<br />

Dans Les Travaux et les fours d'Hesiode, EATTIc, ['incertitude par rapport it<br />

l'avenir, est Ie seul mal it ne pas s'echapper de la jarre de Pandore. La liberation<br />

des maux genere des conditions de precarite, qui sont necessaires it<br />

l'epanouissement d'EATTic. Alors que les autres maux parcourent librement Ie<br />

monde, EAlTlc, comme Pandore, prefere rester a la maison en compagnie de<br />

l'homme, un mal aimable que l'homme embrasse. Puisqu'elles promettent<br />

toutes deux l'abondance, dIes incitent a la paresse. C'est pourquoi EAlTic<br />

represente un danger pour l'homme, don't la seule chance de succes dans Ie<br />

cosmos voulu par Zeus passe par un travail incessant.<br />

UNE NOUVELLE ALLUSION A SIMONIDE CHEZ CHORIKIOS DE GAZA<br />

EUGENIO AMATO<br />

Choricius of Gaza, Apologia mimorum p. 344.4-8 Foerster-Richtsteig, seems to<br />

reflect a passage of Simonides (fr. 93 Page). However, an examination of the<br />

context allows the suggestion that this late author is not alluding to Simonides<br />

directly but rather through Plato's imitation.<br />

"GOODBYE TO ALL THAT":<br />

PROPERTIUS' MAGNUM ITER BETWEEN 3.16 AND 3.21<br />

JACQUELINE CLARKE<br />

Cet article traite de la fa

que ces poemes sont organises strategiquement pour mener au grand voyage<br />

(magnum iter) de Properce (3.21) vers l'erudite Athenes.<br />

FEMALE AND OWARF GLADIATORS<br />

STEPHEN BRUNET<br />

Les historiens ont longtemps admis que les empereurs romains faisaient combattre<br />

des femmes gladiateurs contre des nains pour produire une etrange<br />

parodie des combats de l'arene. Or. un nouvel examen des temoignages au sujet<br />

des gladiatrices indique que ces paires de combattants n'ont jamais existe. En<br />

realite. les femmes gladiateurs et venatores n'etaient pas un element commun<br />

des jeux. La raison pour laquelle ces guerrieres ont frappe l'esprit de leurs contemporains<br />

a mal ete comprise. En effet. ce n'etait pas leur inaptitude amusante<br />

que l'on appreciait chez elles. mais leur talent a faire preuve de valeur guerriere<br />

alors qu'on les en considerait incapables.<br />

EN QUETE D'UN REEL LINGUISTIQUE. OU LA CONSTRUCTION<br />

DES LANGUES ANCIENNES PAR LA TRADITION PHILOLOGIQUE<br />

PASCALE HUMMEL<br />

Philology constitutes a major part of the history of the tradition, just as the tradition<br />

is substantially defined by its philological character. Philology and the<br />

tradition-and both together. through the philological tradition-assure the<br />

transmission of previously constituted knowledges, at the same time as they<br />

interrogate all their details. The structural discrepancy that diachrony introduces<br />

constitutes languages that have become ancient (i.e.. dead) as objects. This<br />

study analyzes how philological reality (by nature epistemological and historiographical)<br />

takes account of the linguistic reality of the languages in question.<br />

and defines the nature of this reality.

Mouseion, Series III. Vol. 4 (2004) 107-119<br />

©2004 Mouseion<br />

HOPE IN A JAR 1<br />

LIZ WARMAN<br />

The significance of the EATTic in the TT180c of Hesiod's Pandora story has<br />

been the subject of protracted and inconclusive scholarly debate. The<br />

Pandora narrative as a whole has often been thought deficient in coherence.<br />

West, editor of the standard text of the Works and Days,2 finds<br />

two stories inadequately blended, the first in which Pandora herself is<br />

the evil promised as punishment for the theft of fire, the second in<br />

which the jar is the source of all evils. He calls the final product"an unusually<br />

clear instance of the way narrative inconsistencies arise as old<br />

stories are retold. "3 Nagy. on the other hand, finds the Works and Days<br />

to be characterized by "cohesiveness and precision," and calls for "rigorous<br />

internal analysis"4 on the part of Hesiod's readers to demonstrate<br />

that coherence. I believe that such an analysis should at least be attempted<br />

before West's judgement against Hesiod's mastery of his material<br />

is accepted.<br />

I will argue for a general definition of EAlTic as emotion-tinged uncertainty<br />

about the future. and discuss possible translations of EAlTlc as<br />

well as Greek authors' evaluations of it. I will then follow the path taken<br />

by Vernant,5 whose reading of the Pandora story has been lauded as<br />

"completely persuasive."6 While I subscribe in the main to Vernant's<br />

interpretation and offer support for several of his conclusions, I will<br />

sometimes diverge from him and offer correctives to certain of his<br />

, This title is borrowed from Charles Revson, founder of Revlon, who himself<br />

unwittingly borrowed Hesiod's image of delusive promise when he called<br />

his cosmetics "hope in a jar" (Peiss [r998] 200).<br />

2 West (1978) is the text cited throughout this essay. unless otherwise noted.<br />

3 West (lg66) 307. The second-century A.D. version of the story found in<br />

Babrius (58) is held up by many as a model of coherence. In it, a man with no<br />

self-control opens a jar full of good things given to men by Zeus. Most of the<br />

goods fly out and are lost. Only EAnle remains in the jar. The inference is obvious:<br />

good hope is preserved to help men face a dreadful world. With admiration<br />

for Babrius' lucidity goes the conviction that his story "more closely reflects<br />

the original sense of the myth than does the version forced upon posterity<br />

by Hesiod" (Panofsky [1956] 6; d. Cow [r914] 106; Rudhardt [1986]235)·<br />

4 Nagy (19go) 80. 82.<br />

5 Vernant (lg81). id. (1989).<br />

6 Clay (2003) 10 1.<br />

107

II2 LIZ WARMAN<br />

within the context of early Greek literature. uncontroversiaVo In the<br />

Theogony. Hesiod's race of women resembles drone-bees who stay inside<br />

the beehive (EVToc8E IlEVOVTEC. 598). EAlTlc. figured as a woman in a<br />

house. is associated in its immediate context with Pandora. the first<br />

woman ever made. 2'<br />

As Pandora is taken to wife by heedless Epimetheus. so. as Hesiod's<br />

image implies. EAlTlc is admitted into Epimetheus' house. EAlTlc. like a<br />

bride. lives with a man. becomes part of his household. Diseases. by<br />

contrast. wander the world freely of their own devices (atJTOllaTol. Op.<br />

103). completely beyond a householder's ken. 22 What Hesiod means. according<br />

to Dover. is that man is the overseer of his own EATIIc, but at the<br />

mercy of diseases. 2J This overstates the control men have over EATIlc.<br />

Diseases, EAlTlc and Pandora are all divine gifts and therefore cannot be<br />

avoided. They are part and parcel of the human condition. But whereas<br />

diseases are known evils, never willingly accepted. EAlTlc is, like Pandora.<br />

an evil that men will embrace (KaKov all

HOPE INA JAR II3<br />

less undeniably bad thing. a delusive "hope. "24<br />

Interpreters who have missed the Pandora-EATTic analogy have supposed<br />

Hesiod's €ATTic to be a good thing. Moschopulus infers that Zeus<br />

punishes men by leaving EATTic in the jar "so as to leave them no trace of<br />

encouragement" (we I-lllOE Ixvoe TTapal-lveiae a\JTole EeXeElv. ad Op. 96).<br />

For West. EATTIc is an "antidote to present ills." but one permitted to<br />

men by Zeus. 25 Picard explains the presence of good EATTIe in a jar otherwise<br />

full of ills as Hesiod's incomplete reduction of the two (sid TTieOl<br />

of Zeus in 11. 24.527 to a single nieoe with mixed contents. Hesiodic pessimism<br />

leads to an attempt to suppress the jar of goods altogether.<br />

"mais il se trahit. en y laissant l'Esperance."26 Recently. Lauriola has<br />

proposed that the jar's mixed good and bad contents make it a match for<br />

the fallen world itsel£.2 7 But any reading that entails an unhomogeneous<br />

mixture in the jar is. as Fink has noted...nicht logischer. "28<br />

That homogeneity must be maintained is strongly suggested by the<br />

contents of actual storage nieOl. which held, for example. only grain.<br />

only oil. only wine. 29 Accordingly. the jars on the threshold of heaven<br />

from which Zeus dispenses changes to men's fortunes store goods separate<br />

from ills (11. 24.529-30). No post-Hesiodic version of our story<br />

makes the contents of the jar a mixture of goods and ills. 3D Philodemus<br />

(On Piety 51.4) reports the fall of men through the escape into the world<br />

of ills from a jar containing only ills. while Macedonius (AP IO.7r) and<br />

Babrius (58) depict the fall as the flight of goods from jars containing<br />

only goods. EATTIe in the Pandora story must be regarded as an ill remaining<br />

in a jar that once contained it and other illsY<br />

24 Emphasis here is on the visual aspect of womanly EAnlc. But Pucci (1977)<br />

105 implies another link between Pandora and EAnlc: "The discourse of Elpis is<br />

without grounds and far from truth. tending towards emptiness and vanity."<br />

Pandora also lies (Op. 78).<br />

25 West (1978) 169.<br />

26 Picard (1932) 54.<br />

27 Lauriola (2000) 12-13.<br />

28 Fink (1958) 70.<br />

29 For the use of ni801 as storage jars on MBA Crete see Cullen and Keller<br />

(1990) 190-191; for their use in LBA Macedonia see Wardle (1987) 317-318,328<br />

329: for their use in Dark Age Boeotia see McDonald (1983) 37-40.<br />

3D Panofsky (1956) 7.<br />

3' A recent interpretation by Beall (1990) 227-230 preserves homogeneity.<br />

but at too great a cost. Beall urges us to relinquish the idea that the jar ever contained<br />

any ills. Goods flew out when Pandora opened it. and EAnlc is a good to<br />

combat ever-present ills. Beall thus overlooks the flight of diseases from the jar<br />

which Hesiod elaborates in detail.

HOPE INA JAR II7<br />

must teach her to have "careful ways" (neea KESVcl. Op. 699). Thus the<br />

inherently evil ways the woman inherits from Pandora (Op. 67. 78) are<br />

ameliorated and she is. as far as possible. redeemedY In other wordsand<br />

this is hardly surprising within the context of our poem-a man<br />

has to work on his wife just as he must work the fields. So also. we may<br />

infer. a right-minded man will "work on" his essentially evil EAlTlc. Its<br />

trap will be evaded only if a man maintains a wary attitude towards its<br />

beautiful promise and keeps on working. Working through adversarial<br />

EAlTlc. then. is a portion of fallen men's toiL<br />

Hesiodic EAlTlc is inextricably bound to the earth. The lTieoe in which<br />

it resides would have been set deeply into the ground, in effect burying<br />

EAlTlc in the soiL EAlTlc comes into men's world together with the need to<br />

work the earth hard. The earth. changed by an angry Zeus from endlessly<br />

fruitful to fruit-concealing. is the home of EAlTic. EAlTlc presents a<br />

heartwarming vision of future riches to be won from the earth. a vision<br />

that must remind men of a lost age of plenty and ease. of nearness to<br />

godhood. Men nowadays inhabit a fragment of Zeus' cosmos whose<br />

beauty is delusive. whose promise is made and then withheld. whose<br />

"hope" seems to be a resource but is. in fact. an obstacle to success. 43<br />

DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS<br />

UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO<br />

TORONTO. ON MS5 2E8<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Beall. E.F. 1990. "The contents of Hesiod's Pandora jar." Hermes I IT 227-230.<br />

Broccia. G. 1958. "Pandora. il pithos e la elpis." PP 13: 296-309.<br />

Carson. A. 1990. "Putting her in her place: Women. dirt. and desire." in O.M.<br />

Halperin. J.J. Winkler. F.r. Zeitlin. eds.. Before Sexuality: The Construction of<br />

Erotic Experience in the Ancient World. Princeton. 135-169.<br />

Clay. J.5. 2003. Hesiod's Cosmos. Cambridge.<br />

Cohen. O. 1989. "Seclusion. separation. and the status of women in Classical<br />

Athens," Greece and Rome36: 3-15.<br />

Cullen. T., O.R. Keller. 1990. "The Greek pithos through time: Multiple functions<br />

and diverse imagery," in W.O. Kingery, ed. The Changing Roles of Ceramics<br />

in Society 26.000 B.P. to the Present. Westerville, OH. 183-2°9.<br />

42 Cf. Zeitlin (1996) 71. The need to train one's wife is a topic addressed again<br />

by Ischomachus in Xenophon's Oeconomicus. For discussion of this wifely education<br />

and its implications for the Greek view(s) of women. see Murnaghan<br />

(1988); Pomeroy (1984) and (1989).<br />

43 I would like to dedicate this essay to my Greek class of 200213. with thanks<br />

and love.

IIB LIZ WARMAN<br />

Dover, K.J. 1966. "Aristophanes' speech in Plato's Symposium," fHS86: 41-50.<br />

Evelyn-White, H.G., ed. and trans. 1919. Hesiod, The Homeric Hymns and<br />

Homerica. Cambridge, MA/London.<br />

Fink, G. 1958. Pandora und Epimetheus: Mythologische Studien. Diss. Erlangen.<br />

Frazer, J.G., trans. and comm. 1898. Pausanias' Description of Greece, n. London.<br />

Gow, A.S.F. 1914. "Elpis and Pandora in Hesiod's Works and Days," in E.C<br />

Quiggan, ed. Essays and Studies Presented to William Ridgeway. Cambridge.<br />

99-109.<br />

Hubbard, T.K. 2001. '''New Simonides' or old Semonides? Second thoughts on<br />

POxy 3965 fro 26," in D. Boedeker, D. Sider, eds. The New Simonides: Contexts<br />

ofPraise and Desire. Oxford. 226-23 I.<br />

Kahn, CH. 1979. The Artand Thought ofHeraclitus. Cambridge.<br />

Krafft, F. 1963. Vergleichende Untersuchungen zu Homer und Hesiod. Hypomnemata<br />

6. G6ttingen.<br />

Lauriola, R. 2000. '''EAlTis e la giara di Pandora (hes. Op. 90-104): 11 bene e il<br />

male nella vita dell'uomo," Maia 52: 9-18.<br />

Leinieks, V. 1984. "'EAlT1S in Hesiod, Works and Days 96," Philologus 128: 1-8.<br />

Loraux, N. 1978. "Sur la race des femmes et quelques-unes de ses tribus," Arethusa<br />

I I: 43-87.<br />

Mazon, P., ed. and comm. 1914. Hesiode: Les Travaux et les fours. Paris.<br />

McDonald, W.A. et al., eds. 1983. Excavations at Nichoria in Southwest Greece<br />

III: Dark Age and Byzantine Occupations. Minneapolis.<br />

McLaughlin, J.D. 1981. "Who is Hesiod's Pandora?," Maia 33: 17-18.<br />

Murnaghan, S. 1988. "How a woman can be more like a man: The dialogue between<br />

Ischomachus and his wife in Xenophon's Oeconomicus," AfP 15: 9-22.<br />

Nagy, G. 1990. Greek Mythology and Poetics. Ithaca.<br />

Paley, F.A., ed. and comm. 1883. The Epics ofHesiod. London.<br />

Panofsky, D. and E. 1956. Pandora's Box: The Changing Aspect of a Mythical<br />

Symbol. New York.<br />

Peiss, K. 1998. Hope in a far: The Making of America's Beauty Culture. New<br />

York.<br />

Pertusi. A., ed. 1955. SchoJia Vetera in Hesiodi Opera et Dies. Milan.<br />

Picard, C 1932. "Le peche de Pandora," L'Acropole T 39-57.<br />

Pomeroy, S.B. 1984. "The Persian King and the Queen Bee," AfAH9: 98-108.<br />

__. 1989. "Slavery in the Greek domestic economy in the light of Xenophon's<br />

Oeconomicus," Index IT 11-18.<br />

Pucci. P. 1977. Hesiod and the Language ofPoetry. Baltimore.<br />

Rudhardt, J. 1986. "Pandora, Hesiode et les femmes," MH43: 231-246.<br />

Verdenius, W.J. 1971. "A hopeless line in Hesiod Works and Days 96," Mnemosyne24:<br />

225-231.<br />

Vernant, J-P. 1981. "The myth of Prometheus in Hesiod" (trans. J. Lloyd), in R.L.<br />

Gordon, ed. Myth. Religion and Society. Cambridge. 43-56.<br />

__.1989. "At man's table: Hesiod's foundation myth of sacrifice" (trans. P.<br />

Wissing), in M. Detienne, J-P. Vernant, eds. The Cuisine of Sacrifice Among<br />

the Greeks. Chicago. 21-86.

HOPEINA JAR JIg<br />

Waltz. P. 1910. "A propos de l'elpis hesiodique," REG 23: 49-57.<br />

Wardle. K.A. 1987. "Excavations at Assiros Toumba 1986: A preliminary report."<br />

ABSA 82: 313-329.<br />

Weizsacker, P. 1897-1902. "Pandora," in W.H. Roscher. ed, Ausfiihrliches Lexicon<br />

der griechischen und romischen Mythologie, III. Leipzig. 1520-1530.<br />

West. M.L.. ed. and comm. 1966. Hesiod: Theogony. Oxford.<br />

__' ed. and comm. 1978. Hesiod: Works and Days. Oxford.<br />

Zeitlin, F.I. 1996. Playing the Other: Gender and Society in Classical Greek Literature.<br />

Chicago/London.

UNE NOUVELLE ALLUSIONIi SIMONIDE 123<br />

au A6yoc. Ie rheteur ecrit :<br />

01 CVIlIlOXOUVTEC tmOTTTOVC TTPCcYIlOCI AOyOlC Ti) IlEV yAwTTlJ TOU<br />

TTOplOVTOC q>EpOVCI KOCIlOV, T4> OE TpOTTI+> OI0130Anv, OET OE IlnTE TTlV<br />

aOIKOV tmOVOIOV EVAo13ETceOl IlnTE 13ICcsEc801 TTlV OAn8EIOV' TO IlEV<br />

yap OTTi8ovov, TO OE YEIlEI OEIAioc. WV OVOETEpOV oTIlOl PrlTOpl<br />

TTpETTEIV.<br />

Les discours qui soutiennent des faits suspects apportent la gloire a la<br />

langue de rorateur.la calomnie pour son attitude. Mais il faut eviter a<br />

la fois de craindre Ie sou}J

Mouseion. Series III, Vol. 4 (2004) 127-143<br />

©2004 Mouseion<br />

"GOODBYE TO ALL THAT": PROPERTIUS' MAGNUM ITER<br />

BETWEEN ELEGIES 3. 16 AND 3.21'<br />

JACQUELINE CLARKE<br />

Propertius' third book of elegies is a very interesting study because<br />

within it he makes the transition from writing almost exclusively on<br />

love to elegies on other themes. Hubbard observes that the book deserves<br />

a lengthy and complete analysis because it is one of the rare<br />

ancient books in which we can see a poet discontent with what has<br />

brought him success and striving for a new manner. 2<br />

By examining<br />

this work we gain insight into Propertius' attempts to adapt the poetic<br />

form of elegy to meet external and internal pressures and trace his<br />

evolution as a poet.<br />

As many critics have observed, from the very outset the book has a<br />

different feel to iP In the first two books of elegies Propertius' mistress<br />

Cynthia dominates the initial poems. In I. I Cynthia prima corne<br />

as the first words and in 2. I Propertius claims that it is his mistress<br />

rather than the Muse Calliope who inspires him (3-4). The opening of<br />

Book 3, however, is quite different. Propertius neither addresses Cynthia<br />

nor talks about her but summons the shades of Callimachus and<br />

Philetas (I). With his call upon Greek models. Propertius signals that<br />

there will be a departure from personal love elegy, for. as Hubbard<br />

observes, love elegy did not choose to represent itself as the result of a<br />

successful plundering expedition from Greece. 4 When a few lines later<br />

I This article was first delivered as a paper at the Department of Greek and<br />

Roman Studies at the University of Calgary, Alberta in November 2003. I am<br />

grateful for the feedback I received on my paper on that occasion. especially from<br />

Professor Peter Toohey who made a number of helpful suggestions. My thanks<br />

also to Professor Butrica for his comments on my article.<br />

2 M. Hubbard. Propertius (London 1974) 92. All quotations from Propertius are<br />

from Barber'socr edition (1960).<br />

3 H.E. Butler and E.A. Barber, The Elegies ofPropertius (Oxford 1933) xii; ].L.<br />

Marr, "Structure and sense in Propertius III." Mnemosyne21 (1978) 266.<br />

4 "Whether because the Greek genre. the epigram. that elegy derived from was<br />

so minor or because of the poets' consciousness that Roman elegy as it had developed<br />

did not owe its form to any Greek poet. love elegy did not chose to represent<br />

itself as the result of a successful plundering expedition" (Hubbard [above. n.<br />

2]69). }.L. Butrica argues that the type of learned Hellenistic elegy. exemplified by<br />

Callimachus, to which Propertius aspires is almost directly antithetical to Roman<br />

love elegy: "The Amores of Propertius; Unity and structure in Books 2-4."<br />

127

I28 JACQUELINE CLARKE<br />

he makes the claim that he is the first to write on Italian subjects in<br />

Greek style (4) he echoes Horace who makes a similar claim in Carm.<br />

3.30.5 Once again the implication is that Propertius intends to move<br />

away from the quintessentially Roman world of the love elegists.<br />

But Propertius' departure is by no means sudden or abrupt. In the<br />

second poem he makes a return (redeamus. I) to the customary round<br />

of love elegy. Indeed poems with Cynthia or love as their main theme<br />

constitute at least one half to two thirds of the book (for instance. elegies<br />

2. 5. 6. 8. 10. IS. 16. 19. 20. 24. 25). These are interspersed with a<br />

curious collection of elegies. some on or to political personages such as<br />

Caesar (4) or Maecenas (9). some on women (13. 14), and some "hybrid"<br />

poems such as elegy II. which begins like a love poem but turns<br />

into a political poem on the fall of Cleopatra. It has often been observed<br />

that this book has an experimental or investigatory air and<br />

Marl' comments that Propertius experiments with hybrid forms to a<br />

degree not found elsewhere in Augustan poetry.6<br />

The book is thus somewhat of a "mixed bag." but for it to be successful<br />

as an entity. the two concluding elegies where Propertius dismisses<br />

Cynthia in sarcastic and biting tones should appear a logical<br />

consequence of what has gone before. In these two final poems Propertius<br />

discards his puella by telling her that her beauty no longer has a<br />

hold upon him (24.1-2). announcing that her tears will not move him<br />

in the slightest (25.5) and envisaging the lonely and decrepit old age<br />

that will descend upon her once her charms have faded (25.11-16).<br />

This should not come as a surprise to the reader; there need to be enough<br />

clues in the previous elegies for the reader to be able to accept<br />

this dismissal and. in company with Propertius. move away from Cynthia.<br />

Propertius has to be able to bring the reader with him in his<br />

great journey towards Book 4. 7<br />

ICS21 (1996) 101. 138. Even rB. Debrohun. Roman Propertius and the Reinvention<br />

ofElegy (Ann Arbor 2003). who is of the opinion that Callimachus had a significant<br />

influence on the love elegies of Propertius' first three books (2). admits that<br />

in Book 4 Propertius turns to a more direct engagement with the Greek poet (8).<br />

5 princeps Aeolium carmen ad ltalos / deduxisse modos. "I am the first to<br />

have adapted Aeolian Song to Italian verse" (13-14).<br />

6 Marl' (above. n. 3) 267.<br />

7 Scholars debate exactly what Propertius sets out to achieve in Book 4 and<br />

how he fulfils his role as a Roman Callimachus. R.J. Baker thinks that it was the<br />

aetiological elegies of Book 4. inspired by Callimachus' Aetia. that gave Propertius<br />

the scope to explore nobler themes: "The military motif in Propertius." Latomus<br />

27 (1968) 348. Butrica (above. n. 4) 107 basically agrees with this view. suggesting<br />

that in Book 4 Propertius tries to realize his aspirations of becoming a<br />

Roman Callimachus by imitating his Aetia while resisting Cynthia's persistent

"GOODBYE TO ALL THAT" 129<br />

This is the major question of this article. How does Propertius indicate<br />

his gradual disengagement from Cynthia and effect the transition<br />

to other forms of poetry?8 How is the reader made aware of the evolution<br />

of his poetic intent? This article will argue that the transition is<br />

effected largely between elegies 3.16 and 3.21.<br />

If the love elegies before this group are examined. there is very<br />

little indication that Propertius intends to discard Cynthia. The poems<br />

to and about his puella are the standard fare encountered in Books I<br />

and 2: a poem celebrating his love for Cynthia and her beauty in<br />

elegy 2. fights and reconciliations in elegies 6 and 8. a poem celebrating<br />

Cynthia's birthday in elegy 10. It is only perhaps at elegy 5 that<br />

the reader is given a hint that there may come some closure to the<br />

endless cycle of their relationship. Propertius suggests that, while it<br />

was appropriate in his youth for him to worship Helicon and twine<br />

spring roses round his brow. in his old age he will turn to the study of<br />

natural philosophy (23-4). Here then he poses a question that most love<br />

poets eventually had to deal with: what happens to the lover and his<br />

mistress when they begin to age? But even this poem is to some extent<br />

based on stock materiaI,9 and Propertius' avowed intention to turn to<br />

influence. Hubbard (above. n. 2) 121. on the other hand. argues that a Roman Aetia<br />

was not a particularly novel enterprise and that the influence that Callimachus<br />

exerted on Propertius was more to do with style and perspective; J.P. Sullivan<br />

adopts a similar line. arguing that it was an ironical use of language and a detached.<br />

humorous viewpoint that constituted Propertius' greatest debt to Callimachus<br />

(Propertius: A Critical Introduction [Cambridge/New York 1976] [47).<br />

Most recently. Debrohun (above. n. 4) 27 argues that what Propertius produces is<br />

not pure patriotic elegy but a sort of hybrid discourse between the competing<br />

values of Roma and amor but she modifies this view with the qualification that<br />

Roma tends to dominate most of the elegies

130 JACQUELINE CLARKE<br />

philosophy should not be taken with a great deal of seriousness. It is<br />

not until elegy 17 that he first professes a wish for escape from love. JO<br />

It is between 3.16 and 3.21, therefore, that Propertius' struggle to<br />

free himself from both Cynthia and love poetry becomes most evident."<br />

These two poems are strategically placed within the collection. Indeed,<br />

in several respects they could be said to mirror one another in<br />

reverse. The first describes a journey Propertius makes to Tibur ter<br />

wards his mistress (2), the second a journey he will make to Athens<br />

away from his mistress (I). In the first Propertius states that his union<br />

with his mistress will enable his death (21 -2); in the second he claims<br />

that his separation from his mistress will ensure that his death is not<br />

disgraceful (34). Most significantly the first describes a journey within<br />

Italy, the second one to Greece. The setting of these two poems is part<br />

of the interesting balance between Greek and Roman in Book 3: for<br />

instance elegy 13 castigates the behaviour of Roman women. while<br />

elegy 14 praises the behaviour of Spartan women. In addition the fact<br />

that Propertius associates his departure from his mistress with a journey<br />

to Greece echoes his call upon Greek models at the beginning of<br />

the book and symbolises his move from the introspective Roman<br />

10 E. Courtney. "The structure of Propertius Book 3," Phoenix 24 (1970) 48. Hubbard<br />

(above, n. 2) 114 suggests that it is in elegy 9 that Propertius first indicates<br />

that he will abandon love poetry for a Roman Aetia. But scholars such as Baker<br />

(above. n. 7) 334 argue that this is just another recusatio and that Propertius' intention<br />

to change his poetic style is made conditional upon the unlikelihood of<br />

Maecenas giving up his career. Indeed the poem is too ambiguously phrased and<br />

too vague in expression to be viewed as a clear declaration to break from love<br />

poetry.<br />

II Previous scholarship does not seem to have treated these six poems as a<br />

group. although Man (above. n. 3) 266 does group elegies 16-20 together as<br />

"poems on various themes," and A. Woolley includes them as part of a larger<br />

grouping from 14-22: "The structure of Propertius Book IlL" BICS 14 (1967) 80. The<br />

tendency is to treat 3.21 (a journey to Athens) with 3.22 (a return to Rome), and it<br />

is true that these poems have themes in common that will be dealt with at the end<br />

of this paper. But. as will be demonstrated. 3.21 also has many themes in common<br />

with 3.16 and can be viewed as an answer to the dilemmas set forth in that poem.<br />

Furthermore, as we will see, the four elegies that come between this pair have<br />

verbal and thematic links with one another. encouraging the reader to think of<br />

them as a group and read them in a linear progression. See H. Jacobson. "Structure<br />

and meaning in Propertius Book III," ICS I (1976) 160. who argues that the<br />

structure of Book 3 is mainly a linear one in which the meaning of any individual<br />

poem is defined and developed by the poem or poems which immediately follow.<br />

Butrica (above, n. 4) g8 supports a linear reading with the argument that this is<br />

virtually demanded by the form of the ancient bookroll.

"GOODBYE TO ALL THA T" 13 1<br />

world of love elegy outwards to Greece for fresh inspiration from<br />

Greek learning.<br />

It comes as no surprise that Propertius represents this as a journey.<br />

for. as several scholars have observed. the topos of the journey is<br />

strong in Book 3. 12<br />

In 7. for instance. Paetus' drowning is described as<br />

a mortis iter. a journey towards death (2). In ro. the celebration of<br />

Cynthia's birthday is defined as a journey (natalis iter. 32). But it is<br />

between elegies 3.16 and 3.21 that the journey motif reaches its climax.<br />

All these poems have references of some sort to journeys. journeys of<br />

many different types. There are journeys through time and space.<br />

journeys in Africa. Italy and Greece. journeys through death and beyond<br />

it. As Propertius himself observes at the beginning of elegy 2 I.<br />

the journey he will make is a magnum iter indeed.<br />

Each of these poems from 3.16 to 3.21 will now be examined for the<br />

stages in the progress of this journey. Within this group of poems<br />

there is an interesting mixture of references to Propertius' monobiblos<br />

and Horace's Odes. In many of these elegies Propertius deliberately<br />

echoes the situations and motifs of elegies in his monobiblos; it is as<br />

though he revisits his former passion in order to farewell it. At the<br />

same time. by paying tribute. even in ironic tones. to Horace's Odes.<br />

Propertius suggests the widening of his outlook.<br />

Elegy 16 is where the journey begins. The poem begins in typical<br />

love elegy fashion in the middle of the night with a letter that comes<br />

from Propertius' mistress summoning him to visit her in the fashionable<br />

resort town of Tibur:<br />

Nox media. et dominae mihi venit epistula nostrae:<br />

Tibure me missa iussit adesse mora.<br />

Midnight. and a letter has come to me from my mistress.<br />

bidding me to be present at Tibur without delay.<br />

(1-2)<br />

Propertius allays his fears about travelling on the night-time roads by<br />

reminding himself that the lover is protected by his love wherever he<br />

goes.<br />

nec tamen est quisquam. sacros qui laedat amantis:<br />

Scironis media sic licet ire via.<br />

Yet there is none would hurt protected lovers:<br />

they can travel even in the middle of Sciron's road.<br />

(lI-I2)<br />

IZ M.C}. Putnam. "Propertius' third book: Patterns of cohesion." Arethusa 13<br />

(1980) 107. The journey motif throughout Book 3 was also the subject of a conference<br />

paper delivered by P. Lee-Stecum at the 2001 Australian Society for Classical<br />

Studies Conference, University of Adelaide.

132 JACQUELINE CLARKE<br />

Like the love elegies that corne before it in Book 3. this is based on a<br />

stock idea. I3 The concept also occurs in Hor. Carm. 1.22. in which Horace.<br />

wandering beyond the boundaries of his Sabine farm. is saved<br />

from a potential wolf attack by the fact that he is singing of his beloved.<br />

14 Both Propertius and Horace. therefore. claim that lovers are<br />

protected; within this claim. however. lies the implication that for lovers<br />

the external world is a dangerous place. To Horace anything outside<br />

the boundaries of his Sabine farm constitutes a threat (an idea that<br />

also occurs in his Carm. 1.17). while Propertius' extravagant claims of<br />

protection in his poem ring a little hollow in the light of his attitude to<br />

the external world in his monobiblos. In his first book Propertius displays<br />

a state of mind cornmon in love poetry. Love is often bound up<br />

with a sense of place; the poet is usually restricted or restricts himself<br />

and his mistress to a particular locality. usually Rome and its environs.<br />

Attempts by him or his mistress to move outside this environment constitute<br />

a threat to the relationship. In 1.6 Propertius rejects an invitation<br />

by Tullus (who will reappear in 3.22) to make a journey to learned<br />

Athens (doctae Athenae) and the wealth of Asia on the grounds that he<br />

will not be able to endure Cynthia's distress (13-18). In I.II Cynthia's<br />

absence in the notorious watering place of Baiae has Propertius worrying<br />

about the strength of her fidelity (27-8). In particular Elegy 3. I 6<br />

recalls 1.17 (and. to some extent. 1.18) where a premature and unsuccessful<br />

attempt on Propertius' part to run away from Cynthia results<br />

in his isolation in a hostile and desolate environment.<br />

There are several intriguing parallels between 3.16 and I.17 that<br />

suggest that Propertius means the reader consciously to recall the<br />

earlier elegy. In both elegies Propertius envisages how he will be<br />

commemorated after death by the attentions of his mistress; it is his<br />

association with his mistress that makes his death celebrated and his<br />

life worthwhile (1.17.21-4. 3.16.23-4). Even more interesting is the<br />

way in which Propertius picks up a word from the final line of I. I 7<br />

and repeats it with a twist in this poem. This is the participle mansuetus.<br />

from the verb mansuescere. to tame or civilize. In 1.17 Propertius<br />

applies it to the shores to which he will return after his isolation from<br />

Cynthia (mansuetis litoribus. 28). At 3.16.10 he applies the adjective to<br />

Cynthia's very hands. recalling how he was once rejected by her for<br />

13 See R.G.M. Nisbet and M. Hubbard. A Commentary on Horace. Odes Book I<br />

(Oxford 1970) 263.<br />

14 namque me silva lupus in Sabina. / dum meam canto Lalagen et ultra /<br />

terminum curis vagor expeditis. / fugit inermem. "For as I was singing of my<br />

Lalage and wandering beyond the boundaries of my farm in the Sabine woods.<br />

unarmed and free from care. there fled from me a wolf" (9-12).

"GOODBYE TO ALL THAT" 133<br />

an entire year and proclaiming in me mansuetas non habet ilIa manus.<br />

"against me that woman doesn't have civilized hands."J5 Thus. as in<br />

1.17. Cynthia's withdrawal of her favours results in Propertius' isolation<br />

from civilization and everything that is good in life: withdrawal<br />

from her implies a separation from fame. human warmth and his creative<br />

impulse as a poet.<br />

Thus in 3.16 the reader encounters a scenario not very far removed<br />

from 1.17. where his mistress. poetry and civilization are inextricably<br />

entwined in Propertius' mind. How does he disengage himself from<br />

this state of mind and bring himself and the reader to 3.2 I where<br />

separation from Cynthia does not result in a desolate environment and<br />

an ignoble death?<br />

Between these two poems Propertius has placed four elegies: a<br />

poem to Bacchus. a consolatio and two love elegies. Each of these elegies<br />

has a verbal or thematic link to the preceding one. suggesting that<br />

they should be read as a sequence: in 3.18 there is a reference to Bacchus<br />

(5-6). linking it with 3.17. the hymn to Bacchus. in 3.19 the allusion<br />

to Minos. the judge of the dead (27-8). connects it with 3.18. the<br />

consolatio. and in 3.20 an allusion to a voyage to Africa (4) echoes a<br />

reference to the straits of the Syrtes in the previous poem (7). It is<br />

noteworthy that the love elegies come last in this sequence. Propertius<br />

firstly moves the reader away from the confined and introspective<br />

world of love elegy to the external world and then revisits his relationship<br />

in the light of these outward journeys.<br />

In the two elegies set in the external world (3.17 and 3.18) the balance<br />

of Greek and Roman themes is continued with the first. the poem<br />

to Bacchus. having a Greek setting and the second. the consolatio for<br />

Marcellus. a Roman one. In the first (3.17) Propertius appeals to the<br />

god of wine to help free him from the tyranny of his love (6). the first<br />

time that he professes a wish for escape from love. He speaks of his<br />

love as a fire ablaze within his bones. a curse that only death or wine<br />

will heal (9-10). He promises that if Bacchus cures him he will devote<br />

himself to the god and sing of Bacchus and his legends (13-14. 21-8).<br />

Finally he draws a parallel between his new-found poetic voice and<br />

that of the lyric poet Pindar (39-40).<br />

The journey motif is reiterated in this poem with Propertius' appeal<br />

to Bacchus to give him prosperous sails (da mihi ... vela secunda, 2).<br />

The direction that Propertius travels in this case is towards Horace's<br />

15 Propertius employs only one other instance of this word in his poetry. at<br />

1.9.12. where he describes elegy in opposition to epic: carmina mansuetus levia<br />

quaerit Amor. "civilized Love seeks smooth songs." In this instance as well.<br />

civilization and love are directly linked to Propertius' productivity as a poet.

134 JACQUELINE CLARKE<br />

Odes and the world of Greek lyric poetry. This elegy appears to be a<br />

deliberate echo of Horace Carm. 3.25. where Horace makes an appeal<br />

to Bacchus to enable him to write poetry on political themes'6; Horace<br />

intends to set the eternal glory of great Caesar among the stars and in<br />

the council of Jupiter (3-6). This divine inspiration is important because.<br />

as Horace himself states. he is attempting something completely<br />

new in the history of Roman poetry:<br />

dicam insigne recens adhuc<br />

indictum ore alio<br />

I shall sing something fresh and famous.<br />

never spoken by another mouth<br />

As Williams comments. "this type of poetry was virtually an invention<br />

of Augustan poetry. "'7<br />

It could be argued that Propertius. with this deliberate echo of Horace.<br />

is teasing the reader by implying that he will take a similar political<br />

direction with his work. If this is the case. then the reader's expectations<br />

are not met, for Propertius does not continue the elegy in this<br />

direction but travels rather to the world of Greek mythology and Pindar.<br />

who often included such myths in his poems. 18 But it is interesting<br />

that his claim of inspiration from Pindar anticipates Horace's tribute to<br />

Pindar in his Fourth Book of Odes (4.2.1), for the image of poet as<br />

priest goes back to Pindar. 19 Propertius thus lays claim to a similar<br />

16 Hubbard (above. n. 2) 72 also draws a parallel with the other Bacchic poem<br />

Carm. 2.19. but I agree with J.F. Millar. "Propertius' Hymn to Bacchus and contemporary<br />

poetry." AJPh 112 (1991) 78. that the resemblances to this ode may be<br />

due to nothing more than the conventional literary treatment of the god. Carm.<br />

3.25. on the other hand. has specific verbal similarities to elegy 3.11' see Millar 78.<br />

80.<br />

'7 G. Williams. The Third Book of Horace's Odes (Oxford 1969) 31. In Book 4.<br />

Propertius in his role as a Roman Callimachus once again makes an appeal to<br />

Bacchus (1.62-4).<br />

18 Miller (above.n. 16) 79 agrees with this but further suggests that the elegy<br />

also contains deliberate echoes of Tibullus (81-2) that help to anchor the text in<br />

the elegiac tradition. If this is the case (and Millar admits the verbal echoes are<br />

rather slight). then it is another way of teasing the reader; the elegy has a foot<br />

firmly planted in both worlds leaving the reader uncertain as to which direction<br />

Propertius will take. As Millar comments. "He turns to Tibullus and Horace for<br />

new ideas for his poetic experiment. but in each case ultimately distances himself<br />

from his fellow poets" (86). See Butrica (above. n. 4) 140. who is also of the view<br />

that Propertius' apparent uncertainty of direction in Book 3 is deliberate.<br />

19 Hubbard (above. n. 2) 75. J.K. Newman. Augustan Propertius: The Recapitulation<br />

ofa Genre (Hildesheim 1997) 263 cites the opening of the second Dithyramb<br />

(Sn.-M·74)·

"GOODBYE TO ALL THAT" 135<br />

vatic stance for his achievements. 2o and the fact that Pindar's literary<br />

output included dirges leads naturally into the next elegy.<br />

In 17 Propertius asserted that only death or wine could free him<br />

from the tyranny of love: from experimenting with wine in 17 he<br />

moves on to death in 18. But Propertius does not here. as he does so<br />

often in other poems. envisage his own death. Instead this elegy is a<br />

consolatio or epikedion for Marcellus. Augustus' possible successor.<br />

who died at Baiae. the fashionable watering place on the Bay of Naples.<br />

By following the Horatian-inspired elegy 17 with a poem that is in<br />

fact devoted to a member of the Augustan gens. it seems that Propertius<br />

is again teasing the reader about the direction he will take. But the<br />

elegy does not, on the whole. devote much space to eulogising the Augustan<br />

gens and its achievements. On the contrary. Propertius rather<br />

focuses on the futility of Marcellus' genus and his connection with the<br />

house of Caesar in the face of the all-consuming fires of death:<br />

quid genus aut virtus aut optima profuit illi<br />

mater. et amplexum Caesaris esse focos?<br />

aut modo tarn pleno fluitantia vela theatro.<br />

et per maternas omnia gesta manus?<br />

occidit. et rnisero steterat vicesimus annus.<br />

How did he benefit from his birth or courage or<br />

His mother's excellence or his union with the house of Caesar<br />

Or the waving awnings of a theatre. recently full.<br />

And all the things his mother's care contrived?<br />

He is dead, his twentieth year the appointed term for him. poor<br />

wretch!<br />

(II-IS)<br />

While it is the case that such lamentations are not untypical in a cansolatio.<br />

21 the true bleakness and negativity of this picture becomes clear<br />

when one compares the lament for Marcellus in Aeneid 6. There. at<br />

least, Virgil devotes more space to eulogising Marcellus' potential in a<br />

series of future statements and unfulfilled conditions. 22 Here any sug-<br />

20 It is at this point in the poem that the echoes of Hor. Carm.3.25 are most<br />

pronounced: haec ego non humili referam memoranda eoturno. "I will recount<br />

such things which are worthy to be recorded in no humble style" in Propertius<br />

3.17.39 echoes Horace's nil parvum aut humili modo. "nothing small or in humble<br />

manner" at 3.25.17. This suggests that this is the real point of the poem. even if. as<br />

Millar (above. n. 16) 79 observes. Propertius' pledge of a Pindaric offering is<br />

somewhat of a fantasy.<br />

21 See P. Fedeli. Praperzio: IJ Libra Terzo delle Elegie (Bari 1985) 553. Compare<br />

Hor. Carm. 1.24.5-12.<br />

22 neepuer Iliaea quisquam de gente Latinos / in tantum spe tollet avos. nee<br />

Romula quondam / ullo se tantum tellus iaetabit alumno ... non Wi se quisquam<br />

impune tuJisset /obvius armato. seu cum pedes iret in hostem. / seu spumantis

136 JACQUELINE CLARKE<br />

gestion of greatness is undercut in the very first line by the phrase<br />

quid ... profuit.<br />

With his elaborate description of Baiae at the beginning of this<br />

elegy. Propertius means the reader to recall the description of Baiae at<br />

the beginning of elegy I I of his monobiblos. the poem where he represents<br />

the place as a threat to the relationship between himself and<br />

Cynthia. 23 The link is an intriguing one. Baiae has fulfilled its threatening<br />

potential in a way different from that anticipated; rather than<br />

sever Cynthia's fidelity. it has cut short t e life of a noble youth.<br />

Barsby comments that "whereas previously as a lover he [Propertius]<br />

had cursed Baiae for its threat to Cynthia's loyalty, now as a poet of<br />

higher pretensions he curses it as a bringer of death to Augustus' protegee.<br />

"24 Notwithstanding this. the link between these two poems helps<br />

to create the suggestion that Propertius is also mourning the anticipated<br />

ending of his union with Cynthia. Indeed. Falkner argues that<br />

readers would initially presume from the opening description that<br />

they were reading another love elegy about Cynthia and only corne to<br />

the realization that it was a consolatio at 9-1025: another instance of<br />

Propertius teasing the reader about his ultimate direction. The melancholy<br />

tone of the elegy. with its message that beauty. power and<br />

wealth will inevitably succumb to death (27-8). highlights the pettiness<br />

of the world of the courtesan where such concerns are all-important.<br />

The journey motif is taken up at the end of the poem where Propertius<br />

envisages the passage of Marcellus' soul into heaven "far from the<br />

paths of men by the road that Claudius the victor of the Sicilian earth<br />

and Caesar trod" (quo Siculae victor telluris Claudius et quo / Caesar.<br />

equi foderet calcaribus armos. "No youth of Italian race shall raise / his Latin<br />

forefathers so high with his promise. nor shall Romulus' land ever / vaunt so<br />

much in any of her offspring ... against him while armed none would have advanced<br />

/ unscathed. whether he would meet the enemy on foot / or dig his spurs<br />

into the flanks of his foaming horse" (875-'7.879-81).<br />

23 As T.M. Falkner. "Myth. setting and immortality in Propertius 3.18." q 73<br />

(1977) 13 points out. the references to Misenus (]) a d Hercules (4) and the erotic<br />

overtones of clausus and ludit (I) would recall the earlier elegy.<br />

24 Barsby (above. n. 8) 136. See also Falkner (above. n. 23) 14.<br />

25 Falkner (above. n. 23) 13. As he observes. 3.18 is the only poem in Book 3 in<br />

which there is no immediately visible connection with the subject of amor. Cynthia<br />

or the writing of love poetry. Of course. as far as the ancients were concerned.<br />

elegy originated as funeral song: G. Luck. The Latin Love Elegy (London<br />

1969) 26. Thus. by placing a funereal elegy at this point in the book Propertius is in<br />

effect taking it back to its roots. The interesting mixture of epikedion and love<br />

elegy has a precedent in Catullus 68, in which a place (Troy) is employed in a<br />

similar fashion to link a lament for Catullus' deceased brother with his struggle<br />

to come to terms with the imperfections of his relationship with Lesbia.

"GOODBYE TO ALL THAT" 137<br />

ab humana cessit in astra via. 33-4). This journey of death with its<br />

sense of separation and transcendence heralds the metamorphosis of<br />

Propertius' poetic output. Its final phrases ab humana via ... in astra.<br />

"from the human pathway into the stars." may contain an echo of<br />

Horace Carm. I.1. where in his role of vates he envisages himself as<br />

separated from the common throng (secernunt populo. 32). striking<br />

the stars with his upraised head (sublimi {eriam sidera vertice.36).<br />

It is with the sense of detachment created by these two outward<br />

journeys that Propertius revisits his relationship with Cynthia in 3.19<br />

and 3.20. In the past. commentators voiced doubts about whether these<br />

two poems. particularly 3.20. referred to Cynthia. and suggested that<br />

another woman was being addressed. 26 More recent scholarship has<br />

taken the view that the poems are to Cynthia. and this is the position<br />

taken by this article. for they lose much of their point if they refer to<br />

another woman. One of the main aims of this section of Book 3 is for<br />

Propertius to disengage himself and the reader from Cynthia. As we<br />

will see. these two poems playa crucial role in this process of separation.<br />

So what is the purpose of 19. a fairly conventional and somewhat<br />

uninspiring poem? There is a point to it. and an interesting one. In this<br />

elegy Propertius claims that women's lust is far stronger than that of<br />

men:<br />

Obicitur totiens a te mihi nostra libido:<br />

crede rnihi. vobis imperat ista magis.<br />

Often you reproach me with men's lust:<br />

Believe me. that passion rather rules you women.<br />

(1-2)<br />

He then proceeds to give a series of mythological exempla. all of which<br />

relate to the power of lust over women. In previous poems the power<br />

balance in the relationship has been very much on Cynthia's side: in<br />

16. for instance. Propertius claimed that he was more afraid of Cynthia's<br />

tears than any midnight foe (8) and in 17 he represents his love<br />

as a fire ablaze within his bones (9). There is no hint of that attitude<br />

here; instead. this elegy represents the poet's attempt to turn the tables<br />

on their relationship. placing the burden of lust squarely on Cynthia's<br />

shoulders. The exemplum that concludes this poem. the story of Scylla<br />

who is drowned by the lover for whom she commits treason (2r-6). is<br />

designed to show the sort of fearful punishment that can lie in wait for<br />

lustful and unrestrained women such as Cynthia. The final picture of<br />

Minos. judge of the dead (27-8). suggests the more judgemental and<br />

26 See further under the discussion of 3.20.

138 JACQUELINE CLARKE<br />

active role that Propertius has now assumed in his relationship with<br />

Cynthia. 27<br />

The journey motif is not especially conspicuous in this poem. but<br />

Propertius does compare Cynthia's uncontrollable nature to a journey<br />

over rough seas:<br />

et placidurn Syrtes porturn et bona litora nautis<br />

praebeat hospitio saeva Malea suo.<br />

quam possit vestros quisquam reprehendere cursus<br />

et rabidae stirnulos frangere nequitiae.<br />

Sooner shall the Syrtes offer a calm haven and savage Malea<br />

Give pleasant shores with a kindly welcome to sailors.<br />

Than any man shall be able to check you in your course<br />

Or shatter the goads of your savage wantonness.<br />

(7-10)<br />

The motif is then elaborated at the end of the poem with the picture of<br />

Scylla's body being dragged through the sea (26). While this metaphor<br />

is by no means unusual (Horace. for instance. employs it of Pyrrha at<br />

Carm. 1.5.5-12). the allusion that Propertius makes to the dangerous<br />

straits of the Syrtes (7), a sandbank off the North African coast. is interesting.<br />

for he will revisit this image in the penultimate elegy of this<br />

book. In 3.24 Propertius indicates that he has done with Cynthia forever<br />

by making a statement to the effect that he has crossed the Syrtes<br />

and cast his anchor: traiectae Syrtes. ancora iacta mihi est (16). This is<br />

another link that ties this elegy more closely to the Cynthia cycle.<br />

The second love poem. 20. begins with a departure from Cynthia.<br />

In ironic fashion it is not Propertius who is leaving Cynthia but another<br />

of her lovers who is setting out for Africa (1-4). picking up the<br />

reference to the Syrtes in the previous poem. But Propertius himself<br />

does not leave Cynthia in this elegy: far from it. for the poem apparently<br />

describes a reconciliation with her. Barsby points out that this<br />

poem has echoes of elegy 8 in the monobiblos in which Cynthia. on the<br />

point of departing with another lover. is persuaded to stay and resume<br />

her affair with Propertius. 28 In both cases the reconciliation is<br />

described in such glowing terms that it recalls the very start of their<br />

affair.<br />

This is the last true love elegy of the book and is particularly in-<br />

27 In view of the fact that Cynthia's real name wa allegedly Hostia. it is possible<br />

that there is a play on the word hoste in line 28 (victor erat quamvis, aequus<br />

in hoste fuit. "though he was victor. yet he was fair to his foe"). Propertius assumes<br />

the role of a just and deserving victor over his conquered enemy. Cynthia<br />

(hoste).<br />

28 ].A. Barsby, "Propertius III 20." Mnemosyne28 (1975) 31.

"GOODBYE TO ALL THA T" I39<br />

triguing, for here Propertius revisits the early stages of his relationship<br />

with Cynthia when there is scarcely a stain upon it. 2 ') Indeed, the<br />

language that Propertius employs of their relationship suggests freshness<br />

and renewal: the night of love is described as though it is the first<br />

(nox mihi prima venit, "the first night of love has come for me," 13), a<br />

new contract is written to seal the new love (15-16). The position of this<br />

poem, so close to the final separation, has puzzled some commentators<br />

to the extent that they feel the mistress referred to cannot be Cynthia.<br />

Camps, for instance, thinks that if Propertius had intended the mistress<br />

to be Cynthia and the placement of this poem to produce an<br />

ironic effect he would have exploited it more definitely.3 0 Several<br />

scholars have convincingly refuted this view. As we will see. there is<br />

plenty of irony in the circumstances and language of this poem and. as<br />

Barsby comments. if it is to Cynthia then the poem gains an extra dimension.3'<br />

Nevertheless there may be a level at which the poem is intended<br />

to be deliberately ambiguous. The reader is left guessing as to<br />

whether the poem describes a reconciliation with an old mistress or a<br />

move to a new one. On one level it doesn't really matter. for, given<br />

the conventions of love elegy. the reader should be aware that. new or<br />

old, the relationship once established will inevitably change and decay.<br />

Thus the placement of this poem, next to Propertius' departure for<br />

Athens in 21 and the bitter repudiations of 23 and 24. is designed to<br />

undercut the sense of joy and the protestations of fidelity that are associated<br />

with this first night of love. 32 Quite a lot of space in the poem is<br />

devoted to describing the contract that will guard the renewed love<br />

against the destructive powers of lust; following immediately after<br />

elegy 19 where women's lust breaks all bounds. the reader must be<br />

aware that this contract is doomed to be broken. Significantly there are<br />

several references to cycles of time in this poem. Propertius appeals to<br />

the moon to lengthen its progress and the sun to shorten its course so<br />

the first night of love is prolonged:<br />

nox mihi prima venit! primae date tempora noctis!<br />

longius in primo. Luna, morare toro.<br />

2') Some commentators. for instance Butler and Barber. have divided this elegy<br />

into two. but I agree with Baker's arguments (above. n. 7,338-339) that it is better<br />

to read the elegy as a single poem where a reconciliation is described as though it<br />

is a new love.<br />

30 W.A. Camps. Propertius. Elegies, Book III (Cambridge 1966) 147. Likewise<br />

Butler and Barber (above, n. 3) 312.<br />

3 1 Barsby (above. n. 28) 36. See also R.J. Baker, "Propertius' lost bona," AJPh 90<br />

(1969); G. Williams, Tradition and Originality in Roman Poetry (Oxford 1968) 417.<br />

3 2 See also Baker (above. n. 31) 333-334: Barsby (above, n. 28) 38.

140 JACQUELINE CLARKE<br />

tu quoque. qui aestivos spatiosius exigis ignes.<br />

Phoebe. moraturae contrahe lucis iter.<br />

The first night of love is coming for me. Give me the length of the<br />

first night.<br />

Moon. linger longer than accustomed over our first union.<br />

You too. Phoebus. who draw out your summer fires too long.<br />

shorten the course of your lingering light.<br />

(I3-14. 1I- 12)<br />

Later he refers to the hours that will be drawn out in conversation and<br />

lovemaking (19-20). But both Propertius and the reader are all too<br />

aware that any attempt to stay time must be doomed to failure. Time<br />

has also been represented as a type of journey in this book. 3J and the<br />

message that emerges from these poems is that journeys inevitably go<br />

on.<br />

Finally we come to the first words of 3.21. the magnum iter which<br />

Propertius will make to Athens to separate himself from his mistress.<br />

The poem describes a journey Propertius will undertake but in a sense<br />

he has already made it. Although at the start of the poem he devotes<br />

some lines to describing the hold that his mistress has over him, his<br />

farewell to her a few lines later is quick and easy.34 He has brought<br />

himself and the reader to the mental state where separation is inevitable<br />

and can be effected with little effort.<br />

Thus, unlike the attempts Propertius has made in the monobiblos,<br />

this separation from Cynthia does not result in his isolation from<br />

civilization but in a journey towards Athens, centre of culture and<br />

learning. The first line shows us the difference:<br />

magnum iter ad doctas proficisci cogor Athenas.<br />

I am compelled to set forth on a mighty journey to learned Athens.<br />

Propertius employs the passive cogor that occurs frequently in his<br />

monobiblos in relation to the servitude of love. At 1.1.8. for instance,<br />

he is compelled to keep adverse gods because of Cynthia's hardheartedness.<br />

at 1.7.7-8 he is compelled to serve his sorrow and bemoan<br />

his harsh lot in life and at I.I8.30 his estrangement from his<br />

mistress means that he is compelled to listen alone to shrill-voiced sea<br />

birds. But in 3.21 he is no longer compelled by love but driven towards<br />

learning (doctas), suggesting his move towards Greek models<br />

33 See Putnam (above. n. 12) WI on the journey of time in 3.10. Cynthia's birthday<br />

elegy: "This happy temporal round. a purely symbolic 'journey: extends<br />

from the reddening sun to the fall of night and a final prayer."<br />

34 Hubbard (above. n. 2) 9 remarks upon what she perceives as a lack of seriousness<br />

in this poem. Its glibness reflects the fact that Propertius has already<br />

brought himself to the state where he can separate himself easily from Cynthia.

"GOODBYE TO ALL THA T"<br />

such as Callimachus. 35<br />

It has been observed that this is the first poem in Book 3 in which<br />

Cynthia is actually named. and that Propertius only calls Cynthia by<br />

name when he is ready to say goodbye to her. 36 Her name occurs at<br />

line 9. and its placement is significant. for it is surrounded by the<br />

words mutatis ... terris. Once again Propertius links Cynthia with<br />

Rome and its environs: changing lands will sever their relationship.<br />

this time for good. Also of significance is the following line. where<br />

Propertius states that once Cynthia is absent from his eyes. love will be<br />

far from his soul: quantum oculis. animo tam procul ibit amor. The<br />

word oculis recalls the very first line of the monobiblos: Cynthia<br />

prima suis miserum me cepit ocellis. "Cynthia first ensnared me with<br />

her eyes. "37 This emphasis on eyes is in keeping with the highly visual<br />

nature of Propertius' poetry. and prepares the reader for the extended<br />

visual metaphor of the journey that follows.<br />

Much as Catullus did in his dismissal of Lesbia at poem II. Propertius<br />

envisages the journey as a means of creating a mental distance<br />

between himself and his mistress. At elegy I.17.25-8 he unfurled his<br />

sails to come back to Rome. love and society; here he hoists his sails to<br />

farewell it:<br />

Romanae turres et vos valeatis. amici.<br />

qualiscumque mihi tuque. puella. vale!<br />

You towers of Rome and you my friends. farewell.<br />

And you. my love. whatever you have been to me. farewell!<br />

(15-16)<br />

The towers of Rome. Propertius' friends and Cynthia are dismissed in<br />

a single couplet. 38 and Propertius then undergoes a sea-change. de-<br />

35 It is true that Callimachus is nowhere mentioned in this poem and the journey<br />

is towards Athens rather than Alexandria. On the other hand. as RF.<br />

Thomas points out in "Callimachus back in Rome." in M.A. Harder et aJ.. OOs..<br />

Callimachus (Groningen 1993) 208. intertextuality and allusion and the crossing<br />

of genre boundaries were a vital part of Callimachean poetics. Athens. as the<br />

source of so many different genres of literature as well as the visual arts functions<br />

as a suitable destination for a student of Callimachus. Fedeli (above. n. 21)<br />

620 takes a somewhat different view. arguing that it is mainly Menander (given<br />

the epithet doctus) who symbolizes Hellenistic refinement. It is interesting. as he<br />

points out. that doctus is also applied to Epicurus; the word is thus used three<br />

times in this poem.<br />

3 6 For instance. Camps (above. n. 30) 15I; Williams (above. n. 31) 417·<br />

37 Compare also 2.15.12 and 2.15.23 for the close relationship between love and<br />

the eyes in Propertius.<br />

3 8 Sullivan (above. n. 7) II6 comments on Propertius' habit of addressing his<br />

friends in his elegies. especially in his monobiblos; he attributes this to the influ-

"GOODBYE TO ALL THA T" I43<br />

of separation for the reader. enabling Cynthia to be dismissed with a<br />

few choice words in the final two elegies of the book. His poetry has<br />

taken a meandering route. keeping the reader guessing about his<br />

ultimate destination: he ventures into the worlds of Greek lyric. sepulchral<br />

elegy. back to his own monobiblos and outwards to the Carmina<br />

of his contemporary Horace. All the time his poetry has continued to<br />

evolve in a new direction. away from the close social world of lovers.<br />

friends and enemies. When Propertius returns to Rome in the elegy<br />

following 3.21. or rather welcomes the soldier Tullus back to it from<br />

his travels in the monobiblos. it is a very different Rome that he comes<br />

to. In glowing. patriotic terms he praises the glories of Rome. contrasting<br />

it favourably with the wonders of other lands in a manner reminiscent<br />

of the passages at the end of Georgics 2 and the start of Odes<br />

1.7. In a sense. the world has been turned on its head from the previous<br />

elegy: Courtney comments that the Greek world that seemed so<br />

appealing to Propertius is now a land of monsters. while Italy has become<br />

attractiveY This is a Rome made strong by the sword and pietas<br />

(19-22). one fit for heroes to contract legitimate marriages and beget<br />

children (39-42); there is no place for Cynthia in this Rome. 43 It is this<br />

Rome that Propertius will celebrate in his first elegy of Book 4.<br />

DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS<br />

SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES<br />

UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE<br />

AUSTRALIA 5005<br />

42 Courtney (above. n. 10) 52.<br />

43 It is worth noting that Putnam (above. n. 12) sees this Rome as something of<br />

a compromise between Imperial Rome and the elegists' Rome: see further Putnam<br />

106. It is possible that there is a degree of irony in this poem: it is interesting<br />

that Propertius devotes much more space to castigating Greece than praising<br />

Rome and that his descriptions of the gods and heroes of Greek mythology<br />

(29-36) have a certain lightness and frivolity to them. While this playfulness may<br />

merely be in imitation of Callimachus (see Thomas [above, n. 351 208) it may also<br />

be meant to suggest that neither the old Greece nor the new Rome should be taken<br />

entirely seriously. [ do not, however, agree with Jacobson's view (above. n. I I,<br />

170) that Tullus' return to Rome in this poem symbolizes a rejection of Propertius'<br />

plan to abandon love elegy. Even if the Rome to which Tullus returns is<br />

viewed with a certain ironic light. it is a very different Rome from the one that<br />

nurtured Propertius' and Cynthia's love affair.

Mouseion, Series III, Vol. 4 (2004) 145-170<br />

16>2004 Mouseion<br />

FEMALE AND DWARF GLADIATORS<br />

STEPHEN BRUNET<br />

While female gladiators hold nearly as much fascination for modern<br />

scholars as they did for the Romans, the motivation and rationale for<br />

having women fight in the arena have not been fully appreciated. I<br />

Symptomatic of this lack of understanding is the long-standing and often<br />

repeated idea that female gladiators were matched against dwarf<br />

gladiators as part of the search for unusual spectacles to please Roman<br />

audiences. What this study will first show is that no grounds exist for<br />

believing that women ever fought dwarfs in the arena. In turn, the uncritical<br />

acceptance of this belief by so many scholars indicates the need<br />

for a complete review of the evidence with a view to establishing when<br />

and under what conditions women actually fought in the arena. The<br />

second part of this study provides such a review, showing in particular<br />

that matches between female gladiators or hunts involving women<br />

were fairly rare. As such. the Romans would have found female gladiators<br />

and women venatores to be interesting in and of themselves.<br />

Moreover. spectacles in which women fought each other or wild animals<br />

were attractive to the Romans because they provided an opportunity<br />

to see individuals who would not normally be considered capable<br />

of bravery demonstrate their valor as warriors. Thus, to the Roman<br />

way of thinking, matching female gladiators with dwarfs or having<br />

them participate in other bizarre spectacles was neither necessary nor<br />

desirable.<br />

DID WOMEN FIGHT DWARFS IN THE ARENA?<br />

The belief that Domitian matched female gladiators against dwarf<br />

gladiators at least once. if not more often, during his reign has a long<br />

I I would like to thank my colleagues Richard Clairmont, R. Scott Smith, and<br />

Stephen Trzaskoma for their willingness to comment on multiple drafts of this<br />

article. Alexis Young of Wilfrid Laurier University kindly pointed out the reference<br />

to Kathleen Coleman's article on the female gladiators from Halicarnassus.<br />

The two readers for Mouseion and the editors, James Butrica and Mark<br />

Joyal. also provided many useful observations and corrections that, I hope.<br />

helped to clarify my arguments greatly. Research funding was provided by the<br />

Dean's Office of the College of Liberal Arts and the Center for Humanities at<br />

the University of New Hampshire.<br />

145

STEPHEN BRUNET<br />

history.2 On the basis of the evidence of Stat. Silv. 1.6 and Dio 67.8,<br />

Navarre stated unequivocally that Domitian was responsible for making<br />

women fight dwarfs in the arena. 3 Essentially the same statement<br />

can be found in Wiedemann's study of the gladiatorial games, although<br />

for support he cites Suet. Dom. 4.1 and Mart. Sp. 68. 4 In his commentary<br />

on Dio. Murison interprets the evidence of 67.8. as Navarre had done,<br />

on the basis of two of Martial's epigrams. 1.43 and 14.213. 5 The assumption<br />

that Dio 67.8 proves that women fought dwarfs reappears in Gunderson's<br />

exploration of the gender issues raised by the Roman games<br />