The Confusion Over Psychopathy (I): Historical Considerations

The Confusion Over Psychopathy (I): Historical Considerations

The Confusion Over Psychopathy (I): Historical Considerations

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

International Journal of Offender <strong>The</strong>rapy and Comparative Criminology<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Confusion</strong> <strong>Over</strong> <strong>Psychopathy</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Confusion</strong> <strong>Over</strong> <strong>Psychopathy</strong> (I):<br />

<strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Considerations</strong><br />

Bruce A. Arrigo<br />

Stacey Shipley<br />

Abstract: This article is the first in a two-part series on psychopathy. <strong>Psychopathy</strong> is an elusive<br />

and perplexing psychological construct. Problems posed by this mental disorder are<br />

linked to changing historical interpretations impacting the current clinical community’s general<br />

understanding of it, especially in relation to Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD).<br />

Accordingly, the researchers provide a thorough analytical review of the major transitions<br />

associated with psychopathy’s historical development. This assessment demonstrates where<br />

and how the nomenclature, meaning, degree of social condemnation, and prognosis for this<br />

mental disorder have changed. Ultimately, this article clarifies much of the uncertainty surrounding<br />

this misunderstood psychological construct.<br />

This article is the first in a two-part series on psychopathy published in the International<br />

Journal of Offender <strong>The</strong>rapy and Comparative Criminology. This article<br />

focuses on the history of psychopathy, mindful of its confusing and complicated<br />

evolution. <strong>The</strong> second article addresses the current and practical implications of<br />

the construct’s development, especially in relation to assessment matters, diagnostics<br />

and treatment, and expert testimony.<br />

As an identified mental disorder and evolving label, psychopathy has a long<br />

history, dating back many centuries. Indeed, researchers have found reference to<br />

psychopathic individuals in biblical, classical, and medieval texts (e.g., Cleckley,<br />

1976; Hare, 1996; McCord & McCord, 1964). Notwithstanding its extensive heritage,<br />

psychopathy has been plagued by changing and uncertain diagnostic<br />

nomenclature. For example, a great deal of confusion currently exists regarding<br />

the relationship between Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD), as identified<br />

by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.)<br />

(DSM–IV), and the modern construct of psychopathy as explained by Cleckley<br />

(1941) and further refined and empirically validated by Hare (1985, 1991).<br />

Although contemporary research supporting the diagnosis of psychopathy is at its<br />

strongest, mental health professionals remain perplexed when diagnosing, treating,<br />

or making recommendations to the court system about these individuals (e.g.,<br />

Gacono & Hutton, 1994; Hare, 1996; Stevens, 1993).<br />

Given the ongoing forensic practice problems that ostensibly pervade the psychopathy<br />

construct, understanding how it has been defined and redefined<br />

throughout history may be warranted. In general, we note that the psychopathic<br />

International Journal of Offender <strong>The</strong>rapy and Comparative Criminology, 45(3), 2001 325-344<br />

© 2001 Sage Publications<br />

325

326 International Journal of Offender <strong>The</strong>rapy and Comparative Criminology<br />

label (i.e., explanation) has changed from the morally neutral view of Pinel<br />

(1801/1962) to the more truculent and disparaging characterization described by<br />

Kraepelin (1915). In addition, the designation itself has evolved from the unpopular<br />

term insanity, to the controversial expression moral, to the present moniker<br />

psychopathic (Hare, 1996; Millon, Simonsen, & Birket-Smith, 1998).<br />

<strong>The</strong> elusiveness of the psychopathic construct and its meaning is further confounded<br />

by the theoretical basis out of which social scientists approach and investigate<br />

this mental disorder (Martens, 2000). Indeed, some researchers invoke<br />

descriptors for psychopathy, implying that the individual experiences morality<br />

problems that are solely personality based (e.g., Craft, 1966; Dinges, Atlis, & Vincent,<br />

1998; Millon et al., 1998), exclusively congenitally or biologically derived<br />

(Ellard, 1988; Schneider, 1958; Smith, 1978), or principally behaviorally<br />

grounded (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Moreover, notwithstanding<br />

these interpretations, Hare’s (1996) empirical and qualitative findings consistently<br />

demonstrate that the psychopath has distinctive affective, interpersonal,<br />

and behavioral attributes.<br />

Relatedly, the clinical construct of psychopathy remains inexplicable and puzzling<br />

not only in name and definition but also in consequence. In short, neither the<br />

mental health nor the criminal justice systems have been successful in rehabilitating<br />

the psychopath. Psychopathic individuals historically and at present are<br />

almost uniformly considered difficult, if not impossible, to treat. Indeed, as Hare<br />

(1993) notes, the psychopath is a “self-centered, callous, and remorseless person<br />

profoundly lacking in empathy and the ability to form warm emotional relationships<br />

with others, a person who functions without the restraint of a conscience”<br />

(pp. 2-3). Moreover, the designation carries with it the message that the individual<br />

is untreatable and cannot be rehabilitated (e.g., Coid, 1998; Ogloff, Wong, &<br />

Greenwood, 1990; Rice, Harris, & Cormier, 1992). As one researcher concludes,<br />

psychopaths are “psychiatrically damaged” (Gunn, 1998, p. 34). Given these<br />

institutional limits and professional practice concerns, establishing any form of<br />

ongoing, efficacious intervention can, at best, be described as unrealistic and misguided<br />

(e.g., Meloy, 1996; Rice, 1997; Simon, 1998; Stevens, 1994).<br />

We submit that the diagnostic confusion surrounding psychopathy (i.e., the<br />

label and its meaning) and the adverse consequences persons in the mental health<br />

and criminal justice systems (potentially) experience in the wake of such a determination,<br />

warrant closer scrutiny. To better appreciate these matters, it is first necessary<br />

to explore psychopathy’s long and convoluted history, commencing in the<br />

early 1800s (i.e., the insights of Pinel) and extending to the present day (i.e., the<br />

contributions of Hare). This historical assessment of psychopathy will illustrate<br />

the varied philosophical and scientific perspectives expressed by researchers on<br />

such matters as (a) general nomenclature, (b) form of social condemnation,<br />

(c) cause of mental illness, and (d) amenability to treatment.<br />

Although clearly not exhaustive, this overview will provide an important backdrop,<br />

making it possible to assess provisionally how psychopathy evolved into a<br />

mental disorder and a pejorative label. In addition, the development of the con-

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Confusion</strong> <strong>Over</strong> <strong>Psychopathy</strong> 327<br />

struct as a DSM diagnosis will be examined. In particular, we will consider the<br />

logic of linking psychopathy, as applied to forensic clients, with the behavioral<br />

diagnosis of ASPD. Ultimately, this degree of historical analysis sheds much<br />

needed light on the changing and misunderstood nature of the psychopathy<br />

construct.<br />

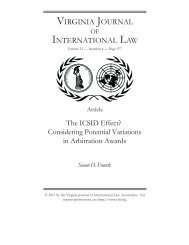

HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF PSYCHOPATHY: A REVIEW<br />

Table 1 summarizes the progression of thought regarding the construct of psychopathy<br />

from the early 1800s to the late 1900s. 1 We note that Table 1 identifies 13<br />

transitions impacting our general understanding of this mental disorder. Each<br />

transition addresses several important components of psychopathy’s’s evolution:<br />

(a) the approximate date of change, (b) the theorist most responsible for the<br />

change, (c) the nomenclature employed, (d) the description of the disorder, (e) the<br />

type/degree of social condemnation, and (f) the perceived prognosis/treatment.<br />

We recognize that the 13 transitions are more overlapping than independent<br />

frames of references; therefore, they should not be interpreted as isolated or exclusive<br />

domains of inquiry. This notwithstanding, the progression of thought contained<br />

within each of the components or categories demonstrates the course of<br />

psychopathy’s development and demonstrates how each has ostensibly functioned<br />

along a continuum (e.g., social condemnation as morally neutral to morally<br />

reprehensible, the disorder’s description based on personality to behavioral traits,<br />

and the locus of treatment from asylums to prisons). In the following sections, we<br />

briefly examine each of these transitions and the unique positions each assumes in<br />

relation to the various categories.<br />

PINEL<br />

As previously stated, the psychopathy construct has a long history with changing<br />

personality patterns and clinical characteristics, dating back through the past<br />

two centuries (Millon et al., 1998). Phillipe Pinel is generally credited with recognizing<br />

psychopathy as a specific mental disorder (Smith, 1978). Pinel advocated<br />

for appropriate, moral treatment rather than cruel interventions (e.g., bloodletting,<br />

cold baths) as the preferred method of intervention for the psychiatrically ill<br />

(Pinel, 1801/1962). Pinel’s contributions occurred in France shortly after the<br />

French Revolution. Prior to this time, France was ruled by a strict class structure<br />

and sanity was judged by the Old Testament of the Bible (Smith, 1978).<br />

In 1801, Pinel observed that some of his patients engaged in impulsive acts,<br />

had episodes of extreme violence, and caused self-harm (Davies & Feldman,<br />

1981; Millon et al., 1998). He noted that these individuals were able to comprehend<br />

the irrationality of what they were doing. <strong>The</strong>re was no evidence of what is<br />

now considered psychosis, and their reasoning abilities did not appear to be<br />

impaired. He described these men as suffering from manie sans délire (insanity

328<br />

TABLE 1<br />

THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF PSYCHOPATHY<br />

Date <strong>The</strong>orist Source Nomenclature Describe Social Condemnation Perceived Prognosis/tx<br />

1801 Pinel manie sans délire insanity w/o delirium morally neutral moral tx; no bleeding<br />

1812 Rush moral alienation total perversion of moral enter social condemnation tx preferred in medical settings<br />

of the mind faculties<br />

1835 Prichard moral insanity deplorable defect in personality social castigation intensifies no volitional control: should be<br />

legal defense<br />

1891 Koch psychopathic strictly congenital personality attempts to shed social depends on the type: chronic or<br />

inferiority types condemnation temporary<br />

1897 Maudsley moral imbecility criminal class affected by criminal class status useless to punish those that<br />

cerebral deficits cannot control their behavior<br />

1904 Krafft-Ebing morally depraved savages in society severe condemnation without prospect of success—<br />

asylums indefinitely<br />

1915 Kraepelin psychopathic most vicious/wicked: born moral judgement/social poor<br />

personalities criminal, liars, swindlers . . . condemnation<br />

1941 Cleckley psychopath detached/narcissistic pejorative poor<br />

interpersonal style

329<br />

1952 APA’s DSM Sociopathic more social perspective; pejorative poor<br />

Personality Cleckley’s features and<br />

Disturbance; some criminal behaviors<br />

antisocial/dyssocial<br />

sociopath<br />

1968 DSM-II ASPD still focused on the personality pejorative poor<br />

dropped dyssocial traits of the psychopath<br />

sociopath; only<br />

antisocial remained<br />

1980/ DSM-III; ASPD chronic violation of social pejorative; includes most typically poor, but symptoms<br />

1987 DSM-III-R norms: Conduct Disorder offenders diminish with age<br />

1985/ Hare’s PCL/ <strong>Psychopathy</strong> 2 Factor Model; reliable and pejorative poor; can become worse<br />

1991 PCL-R valid with tx<br />

1994 DSM-IV ASPD focused on behavioral criteria pejorative equated with poor, but symptoms diminish<br />

criminal with age<br />

NOTE: APA = American Psychiatric Association; DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; ASPD = Antisocial Personality Disorder; PCL = <strong>Psychopathy</strong><br />

Checklist; PCL-R = <strong>Psychopathy</strong> Checklist–Revised; tx = treatment.

330 International Journal of Offender <strong>The</strong>rapy and Comparative Criminology<br />

without delirium) (Dinges et al., 1998; Millon et al., 1998). As Pinel (1801/1962)<br />

explained, “I was not a little surprised to find many maniacs who at no period gave<br />

evidence of any lesion of understanding, but who were under the dominion of<br />

instinctive and abstract fury, as if the faculties of affect alone had sustained injury”<br />

(p. 9). His observations were very controversial during this era, especially<br />

because a low intellect and symptoms of psychosis were the typical criteria for<br />

identifying mental illness (Stevens, 1993).<br />

RUSH<br />

In the early 1800s, Benjamin Rush, an American psychiatrist, also documented<br />

confusing cases that were described by clarity of thought along with<br />

moral depravity in behavior (Millon et al., 1998). However, Rush (1812) went<br />

beyond Pinel’s more affectively based description and maintained that moral<br />

derangement was either a birth defect or was caused by disease. Rush believed this<br />

condition was primarily congenital. As he stated, “<strong>The</strong>re is probably an original<br />

defective organization in those parts of the body which are preoccupied by the<br />

moral faculties of the mind” (p. 112). In addition, Rush held that “it is the business<br />

of medicine to aid both religion and law, in preventing and curing their moral<br />

alienation of the mind” (p. 359). <strong>The</strong> American psychiatrist maintained that the<br />

lack of morality was primarily hereditary, yet unstable environments were largely<br />

responsible for fostering its growth (Smith, 1978). Rush further claimed that<br />

offenders with mental defects were best treated in medical rather than custodial<br />

institutions (Toch, 1998).<br />

Benjamin Rush is recognized as one of the first to begin what has since become<br />

a long-standing practice of social condemnation toward individuals labeled psychopathic.<br />

However, his classification of persons as morally alienated in the mind<br />

did not go without criticism. <strong>The</strong> essence of the criticism was that his clinical<br />

assessment for psychopathy was too generic a diagnosis and was overly inclusive.<br />

As John Adams commented,<br />

Rush is so near to my heart, that I must return to his very interesting Volume. It<br />

seems to me, that every excess of Passion, Prejudice, Appetite; of Love, Fear, Jealousy,<br />

Envy, Revenge, Avarice, Ambition; every Revery and Vagary of Imagination,<br />

the Fairy Tales, the Arabian Nights, in short, almost all Poetry and all Oratory; every<br />

écart, every deviation from pure, logical mathematical Reason; may in Some Sense<br />

be called a disease of the mind. (quoted in Ellard, 1988, pp. 384-385)<br />

PRICHARD<br />

J. C. Prichard (1835) was a British physician and the first to actually coin the<br />

expression moral insanity. Prichard defined moral insanity as “a morbid perversion<br />

of the natural feelings, affections, inclinations, temper, habits, moral dispositions,<br />

and natural impulses, without any remarkable disorder or defect of the

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Confusion</strong> <strong>Over</strong> <strong>Psychopathy</strong> 331<br />

intellect or knowing and reasoning faculties, and particularly without any insane<br />

illusion or hallucination” (1837/1973, p. 16). Prichard agreed with many aspects<br />

of Pinel’s findings; however, he fervently disagreed with Pinel’s “morally neutral”<br />

position toward such individuals (Millon et al., 1998, p. 5). In fact, Prichard<br />

argued that the morally insane exhibited a deplorable defect in personality that<br />

constituted social castigation (p. 5). He postulated that those afflicted knew the<br />

difference between right and wrong but were compelled to engage in reprehensible<br />

behaviors. As Prichard (1835) observed,<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is a form of mental derangement in which the intellectual functions appear to<br />

have sustained little or no injury, while the disorder is manifested principally or<br />

alone in the state of the feelings, temper or habits. In cases of this nature the moral or<br />

active principles of the mind are strangely perverted or depraved; the power of<br />

self-government is lost or greatly impaired and the individual is found to be incapable,<br />

not of talking or reasoning upon any subject proposed to him, but of conducting<br />

himself with decency and propriety in the business of life. (p. 85)<br />

Critics of Prichard’s observations contend that his moral insanity category was<br />

so broad that it encompassed other mental disorders recognized as such today<br />

(e.g., Toch, 1998). This notwithstanding, others note that Prichard’s contributions<br />

added to the clinical perception of what constituted a mental disorder (Millon<br />

et al., 1998). Investigators generally agree, however, that the antisocial or dangerous<br />

acts committed by these individuals were not the cause of the mentally ill designation.<br />

Rather, the overwhelming and irresistible impulses that functioned outside<br />

the person’s control led to the moral insanity classification. Thus, it follows<br />

that moral insanity reduced criminal culpability. Indeed, according to Prichard,<br />

moral insanity should be employed as a legal defense (Toch, 1998).<br />

KOCH<br />

<strong>The</strong> appropriate designation for what is today known as psychopathy underwent<br />

several changes and iterations. For example, a number of German theorists<br />

described a series of trait syndromes for the psychopath (Craft, 1966). In 1891,<br />

Koch used the term psychopathic inferiority to characterize individuals who<br />

engaged in abnormal behaviors due to heredity but who were not insane. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

were determined to have moral defects, but these defects were not equated with<br />

viciousness or wickedness (Ellard, 1988). This new terminology (i.e., psychopathic<br />

inferiority) described emotional and moral aberration based on congenital<br />

factors and found wide acceptance in Europe and America (Smith, 1978).<br />

In part, because of Koch’s findings, clinical and forensic assessment efforts<br />

have recognized, until more recently, that psychopathic inferiority broadly represents<br />

all personality disorders (Millon et al., 1998). Koch’s work was an attempt<br />

to identify personality types. He divided his congenital psychopathic inferiorities<br />

into three groups: (a) psychopathic disposition—psychic tenderness in an<br />

asthenic individual; (b) psychic inferiority—vulnerable types (sensitive and

332 International Journal of Offender <strong>The</strong>rapy and Comparative Criminology<br />

weak), vigorous types (grandiose, troublemaker), and the intermediate types<br />

(blunted nature); and (c) psychopathic degeneration—intellectual and moral failure<br />

caused by cerebral defects (Schneider, 1958, pp. 20-21).<br />

Koch sought to displace much of the social condemnation underscoring<br />

Prichard’s concept of moral insanity (Schneider, 1958). In addition, he attempted<br />

to recast psychopathic inferiority as strictly a congenital disorder. This initiative<br />

was thwarted, however, when the more social perspective of sociopathy emerged<br />

(Ellard, 1988). Despite Koch’s attempts to deviate from what had been considered<br />

moral insanity, the more current conceptualizations of psychopathy still reflect its<br />

derogatory character (Millon et al., 1998). In other words, following Koch, during<br />

the first several years of the 20th century, psychopathy signified nothing more<br />

than abnormality in behavior that was congenital in nature (Schneider, 1958, p. 21).<br />

However, notwithstanding Koch’s efforts, the meaning of psychopathy in subsequent<br />

years once again became something quite pejorative but also something<br />

more reflective of the internal world and personality traits of the individual.<br />

MAUDSLEY<br />

Maudsley (1897/1977) was a British psychiatrist who asserted that persons<br />

prone to moral imbecility could not be rehabilitated in prisons. He believed that a<br />

distinct class of offenders was “marked by a defective physical and mental organization<br />

determin[ing] their destiny ...[and creating] an extreme deficiency or<br />

complete absence of moral sense” (quoted in Toch, 1998, p. 146). Maudsley<br />

argued that moral imbecility was caused by cerebral deficits. As such, he believed<br />

it was useless to punish those who could not control their actions. He identified a<br />

criminal class; namely, “chronic offenders of lower-class origin” (Toch, 1998, p.<br />

147), and wrote the following as evidence of moral imbecility:<br />

When we find young children, long before they can possibly know what vice and<br />

crime means, addicted to extreme vice, or committing great crimes, with an instinctive<br />

facility, and as if from an inherent proneness to criminal actions...andwhen<br />

experience proves that punishment has no reformatory effect upon them—that they<br />

cannot reform—it is made evident that moral imbecility is a fact, and that punishment<br />

is not the fittest treatment of it. (quoted in Toch, 1998, p. 147)<br />

KRAFFT-EBING<br />

Krafft-Ebing (1904) was even less sympathetic toward those considered morally<br />

depraved than was Benjamin Rush. <strong>The</strong> former was among the first to assert<br />

that such individuals were “without prospect of success” and commented that<br />

“these savages...must be kept in asylums for their own [good] and [for] the safety<br />

of society” (quoted in Toch, 1998, p. 148). It was at this historical juncture that<br />

psychopathic individuals were regarded as impervious to rehabilitation and that<br />

chronic social deviance was equated with pathology (Ellard, 1988).

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Confusion</strong> <strong>Over</strong> <strong>Psychopathy</strong> 333<br />

Krafft-Ebing is also credited with discovering several other important and<br />

enduring psychological constructs that present critical implications for the most<br />

violent of psychopaths. For example, he introduced the terms sadism and masochism<br />

into the assessment lexicon (Millon et al., 1998). <strong>The</strong>se terms were derived<br />

from the short stories and other works by Marquis de Sade, a French nobleman<br />

and writer who lived during the 18th century (Millon et al., 1998) <strong>The</strong> Marquis’<br />

stories described the intentional infliction of pain and sexual domination (i.e.,<br />

sadism) as well as the pleasure and sexual gratification or both of being humiliated<br />

or suffering bodily harm (i.e., masochism). Krafft-Ebing claimed that all humans<br />

have an “innate desire to humiliate or hurt” and that “sexual emotion, if<br />

hyperesthetic, might degenerate into a craving to inflict pain” (quoted in Millon<br />

et al., 1998, p. 9). Aggression was considered a normal element of the male sex<br />

drive, which, if exaggerated, could lead to sadism (Millon et al., 1998).<br />

Krafft-Ebing found that sadism in a psychopath was particularly alarming<br />

because those subjected to this mental illness were much more likely to act on<br />

their dangerous impulses.<br />

KRAEPELIN<br />

<strong>The</strong> approach to the disorder of psychopathy derived principally from somatic<br />

descriptors evolved from German theorists who explained it by utilizing massive<br />

typological systems (Craft, 1966). By 1915, Kraepelin expanded Koch’s psychopathic<br />

inferiority terminology to contain categories essentially defined by the<br />

most vicious and wicked of disordered offenders (Ellard, 1988). Prior to<br />

Kraepelin, the categories of psychopathies contained various personality descriptions.<br />

Kraepelin, however, wanted to narrow the classification to only those characteristics<br />

that were the most devastating and most frequently detected by physicians<br />

working in institutions. His psychopathic personalities described in detail<br />

the “born criminal . . . the excitable, shiftless, impulsive types, the liars, swindlers,<br />

antisocial and troublemaking types” (Schneider, 1958, p. 23). Kraepelin portrayed<br />

“morbid liars and swindlers” as manipulative, glib, charming, and unconcerned<br />

for others (Millon et al., 1998, p. 19). Another category designated by<br />

Kraepelin included criminals by impulse, who were overcome by uncontrollable<br />

desires to commit offenses like arson or rape for purposes unrelated to material<br />

gain. A third classification included professional criminals, who acted out of cold,<br />

calculated self-interest rather than from uncontrollable impulse. Finally, a fourth<br />

type consisted of morbid vagabonds, who wandered through life with neither<br />

self-confidence nor responsibility (Millon et al., 1998).<br />

Clearly with these characterizations, Kraepelin moved the focus of psychopathy<br />

back to one of moral judgment and social condemnation. Interestingly, as<br />

Millon et al. (1998, p. 19) note, his categories of psychopathic personalities more<br />

closely represent our conceptualization of psychopathy and ASPD today. This<br />

association is found in Kraepelin’s statements on the classification of antisocial<br />

personalities. He described these disordered individuals as

334 International Journal of Offender <strong>The</strong>rapy and Comparative Criminology<br />

the enemies of society...characterized by a blunting of the moral elements. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

are often destructive and threatening . . . there is a lack of deep emotional reaction;<br />

and of sympathy and affection they have little. <strong>The</strong>y are apt to have been troublesome<br />

in school, given to truancy and running away. Early thievery is common<br />

among them and they commit crimes of various kinds. (quoted in Millon et al., 1998,<br />

p. 10)<br />

CLECKLEY<br />

<strong>The</strong> publication of Cleckley’s text, <strong>The</strong> Mask of Sanity (1941), marked the<br />

beginning of the modern clinical construct of psychopathy, and his characterization<br />

has remained relatively stable to the present day (Hart & Hare, 1997).<br />

Cleckley based his description of the psychopath on observations of White,<br />

middle-class male patients, residing as inpatients of a mental hospital (Dinges<br />

et al., 1998). He acknowledged the confusion caused by the changing psychopathic<br />

nomenclature and the overly inclusive descriptions of past investigators.<br />

Hart and Hare (1997) summarized the essential features of Cleckley’s psychopath<br />

as follows:<br />

Interpersonally, psychopaths are grandiose, arrogant, callous, superficial, and<br />

manipulative; affectively, they are short-tempered, unable to form strong emotional<br />

bonds with others, and lacking in empathy, guilt or remorse; and behaviorally, they<br />

are irresponsible, impulsive, and prone to violate social and legal norms and expectations.<br />

(pp. 22-23)<br />

According to Lykken (1995), Cleckley viewed moral feelings or the human<br />

conscience as learned, and the learning process was directed and reinforced by<br />

emotional feelings. In addition, Cleckley contended that if normal human emotions<br />

were diminished, the development of morality or socialization would be<br />

jeopardized. Ultimately, he found that normally socializing experiences were ineffectual<br />

with psychopaths. <strong>The</strong> conceptualization of the psychopath by Cleckley<br />

focused on the patient’s intrapersonal characteristics or “inferred, nonobservable,<br />

processes . . . such as lack of judgment, impulsivity, an inability to feel remorse or<br />

guilt, an inability to learn from punishment, and rationalizing or blaming others<br />

for one’s behavior” (Dinges et al., 1998, p. 463). Clearly, then, the focus was not<br />

on their criminal history.<br />

Indeed, Cleckley (1941) recognized that many psychopaths never became<br />

involved with the criminal justice system. Moreover, many could succeed in business<br />

or in other endeavors, particularly in those careers that offered considerable<br />

material success. Commenting on the differences between the nonoffending psychopaths<br />

and their criminal counterparts, Cleckley noted that<br />

a very deep seated disorder often exists. <strong>The</strong> true difference between them and the<br />

psychopaths who continually go to jails or psychiatric hospitals is that they [i.e., the<br />

nonoffenders] keep up a far better and more consistent outward appearance of being<br />

normal. (pp. 198-199)

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Confusion</strong> <strong>Over</strong> <strong>Psychopathy</strong> 335<br />

Following these observations, Cleckley (1941) observed that the primary psychopathic<br />

characteristics of glibness, superficial charm, emotional detachment,<br />

and lack of remorse or guilt could be used for successful criminal or noncriminal<br />

careers. Psychopaths can pursue what they want without experiencing anxiety attributable<br />

to a concern for how their actions might impact others. In the long run,<br />

Cleckley argued that the impulsive conduct of psychopaths would frequently be<br />

detrimental to them. In addition, the inability to plan for the future or learn from<br />

consequences were other traits inherent to his interpretation of the psychopathic<br />

personality. Cleckley also described the psychopath’s behavior. As he<br />

commented,<br />

It is impossible for him to take even the slightest interest in the tragedy or joy or the<br />

striving of humanity as presented in serious literature or art. He is also indifferent to<br />

all these matters in life itself. Beauty and ugliness, except in a very superficial sense,<br />

goodness, evil, love, horror, and humor have no actual meaning, no power to move<br />

him. (p. 90)<br />

Cleckley (1941) also said that the psychopath<br />

is lacking in the ability to see that others are moved. It is as though he were<br />

color-blind, despite his sharp intelligence, to this aspect of human existence. It cannot<br />

be explained to him because there is nothing in his orbit of awareness that can<br />

bridge the gap with comparison. He can repeat the words and say glibly that he<br />

understands, and there is no way for him to realize that he does not understand.<br />

(p. 90)<br />

Cleckley’s research on psychopathy and his subsequent classification of its essential<br />

traits reflected a distinct psychiatric category (Ellard, 1988). His conceptualization<br />

of the psychopath identified the impact of heredity on crucial learned behaviors;<br />

that is, a developed human conscience. For example, the psychopath<br />

would be unable to experience the emotions necessary to reinforce moral behavior.<br />

In addition, the psychopath would not experience the typical anxiety that<br />

would cause someone to fear behaving in a socially inappropriate manner.<br />

Evidence concerning the impact of heredity and other supporting data about<br />

this category were presented to the Royal Commission on the Law Relating to<br />

Mental Illness and Mental Deficiency 1954-1957 (Ellard, 1988; Lykken, 1995).<br />

In the wake of Cleckley’s (1941) findings, the word psychopath became popular<br />

among laypersons as well as mental health professionals. Ellard (1988) attributes<br />

this notoriety to the term’s status as both an explanation for and a cause of<br />

depraved and frequent criminal behavior. He cautions, however, that this logic<br />

was as inherently circular and suspect during Cleckley’s period as it is today.<br />

Illustrating the tautological nature of Cleckley’s psychopath, Ellard questions,<br />

“Why has this man done these terrible things? Because he is a psychopath. And<br />

how do you know that he is a psychopath? Because he has done these terrible<br />

things” (p. 387).

336 International Journal of Offender <strong>The</strong>rapy and Comparative Criminology<br />

THE DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL<br />

OF MENTAL DISORDERS (DSM)<br />

<strong>The</strong> first publication of the American Psychiatric Association’s (1952) DSM<br />

renamed the evolving psychopathic construct Sociopathic Personality Disturbance<br />

(Millon et al., 1998). This change demonstrated the fusion of previous psychiatric<br />

explanations with more socially sensitive interpretations. Researchers,<br />

too, began to support this more integrative position. As McCord and McCord<br />

(1964) explained, “In addition to the individual causative factors, consideration<br />

should be given to the cultural factors that may contribute to psychopathy” (p. 87).<br />

Investigators hoped that this psychosocial emphasis would clarify how the individual<br />

was also a part of a group and not just an isolated subject experiencing<br />

internal perversions (Smith, 1978). Interestingly, however, the original DSM criteria<br />

for Sociopathic Personality Disturbance included many of the personality<br />

characteristics set forth by Cleckley (1941) in his description of the psychopath.<br />

<strong>The</strong> focus on internal processes and personality traits would give way to more<br />

behavioral criteria in later DSM editions.<br />

<strong>The</strong> scientific push to explain how actions were determined externally is attributable<br />

to the large behaviorist movement that occurred in the United States during<br />

the mid-20th century. Smith (1978) discussed the social trespass theory that was<br />

prevalent during this period. <strong>The</strong> theory states that specific cultures are responsible<br />

for judging certain behaviors deviant. In other words, actions are considered<br />

abnormal if, and only if, they violate the social and legal boundaries of the group<br />

to which they belong. This focus on deviant behavior was criticized by some<br />

because all classes of criminals (e.g., thieves, sex offenders) were pushed into the<br />

same category (i.e., Sociopathic Personality Disorder) (McCord & McCord,<br />

1964). In effect, the focus shifted from the abnormal internal processes of the psychopath<br />

to include generic and overly inclusive deviant behaviors of many types<br />

of (offending) individuals.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se concerns notwithstanding, the DSM retained personality traits such as a<br />

lack of guilt, anxiety, or a sense of responsibility as a part of the diagnostic criteria.<br />

<strong>The</strong> diagnosis had no requirement for the presence of childhood symptoms (APA,<br />

1952). Another distinction for this diagnosis was the existence of antisocial and<br />

dyssocial sociopaths. <strong>The</strong> dyssocial sociopath was identified as a professional<br />

criminal who could be extremely loyal to his comrades (e.g., members of organized<br />

crime) (Smith, 1978).<br />

DSM-II<br />

<strong>The</strong> dyssocial sociopath distinction was eliminated with the publication of the<br />

DSM-II (APA, 1968). Smith (1978) contended that the extreme loyalty to family<br />

and friends made this classification represent no other pathology except illegal<br />

behaviors. <strong>The</strong> personality characteristics of the psychopath were not conveyed in<br />

the dyssocial sociopath. <strong>The</strong> antisocial classification that remained still focused

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Confusion</strong> <strong>Over</strong> <strong>Psychopathy</strong> 337<br />

on the psychopath’s personality traits. For example, the DSM-II described this<br />

type of individual as callous, impulsive, selfish, and unable to learn from experience<br />

(APA, 1968). However, some critics maintained that the DSM-II did not provide<br />

specific diagnostic criteria for the disorder (Hare, 1996).<br />

DSM-III and DSM-III-R<br />

<strong>The</strong> issue of explicit diagnostic criteria was solved with the publication of the<br />

DSM-III (1980) and the DSM-III-R (1987). Following both manuals, the diagnosis<br />

for psychopathy was called Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD); however,<br />

it no longer focused on personality traits. <strong>The</strong> criteria were changed by emphasizing<br />

behaviors. <strong>The</strong> DSM-III Task Force felt that the clinical inferences necessary<br />

to determine the personality characteristics of a psychopath lowered the reliability<br />

of the diagnosis. <strong>The</strong>refore, a diagnostic shift to behavioral characteristics<br />

commonly associated with the disorder was considered more reliable for identification<br />

purposes than were the personality factors explaining why the behaviors<br />

occurred (Hare, 1996). However, the new criteria were so broad they included<br />

almost every known criminal offense (Stevens, 1993).<br />

This new formulation of ASPD included Conduct Disorder or a history of deviant<br />

behavior before the age of 15 as a necessary element to reach the diagnosis.<br />

This diagnostic criterion is met by finding 3 of 12 types of deviant behaviors<br />

including, among others, lying, truancy, physical cruelty to animals or people,<br />

arson, and fighting (APA, 1987). However, some critics note that this criterion can<br />

also be a self-fulfilling prophecy (e.g., Millon et al., 1998). Indeed, some children<br />

may engage in antisocial behavior as a protective function, rather than a biologically<br />

based psychopathic personality (Lykken, 1995; Widom, 1998).<br />

Examining the presence of antisocial behavior in adolescents, Widom (1998)<br />

explains that abuse or neglect encourages the development of childhood coping<br />

styles that, although adaptive in an dysfunctional home, would not be adaptive as<br />

an adult in other relationships. <strong>The</strong> youth might develop characteristics such as a<br />

lack of realistic long-term goals, manipulation, pathological lying, or superficial<br />

charm to cope in his or her abusive home. Robins (1978) articulating this view,<br />

explained the process through a behavioral sequence of events:<br />

<strong>The</strong> very fact of deviance beginning early in childhood makes a succession of interconnected<br />

problems highly probable. Early truancy leads to leaving school before<br />

graduation, which in turn creates job problems, which then encourages theft, which<br />

leads to jail ...wearetalking about the consequences of severe antisocial behavior<br />

occurring early in childhood. (pp. 269-270)<br />

For the ASPD diagnosis, at least 4 of 10 behavioral categories must be met. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

categories include such things as “inability to sustain consistent work behavior...fails<br />

to conform to social norms with respect to lawful behavior ...isirritable<br />

and aggressive, as indicated by physical fights or assaults” (APA, 1980,

338 International Journal of Offender <strong>The</strong>rapy and Comparative Criminology<br />

p. 345). Other behavioral categories include lying, impulsive conduct, inability to<br />

establish lasting, stable relationships, and a disregard for personal safety (APA,<br />

1987; Stevens, 1993).<br />

At least one member of the DSM-III Task Force was not convinced that this<br />

new diagnosis appropriately represented the psychopathy construct it was<br />

designed to identify and measure. Millon (1981) wrote of his dissatisfaction with<br />

the Task Force’s diagnosis of ASPD, alleging that “the write-up fails to deal with<br />

personality characteristics at all, but rather lists a series of antisocial behaviors<br />

that stem from such characteristics”(p. 182). In addition, he explained that too<br />

great an emphasis was placed on delinquent and criminal behaviors for the diagnosis.<br />

Millon also cited instances where some individuals with similar psychopathic<br />

personalities will express these characteristics in socially appropriate<br />

ways. In other words, he argued that the ASPD diagnosis was overly inclusive.<br />

Following Millon’s (1981) criticisms, not everyone who engages in criminal<br />

behavior experiences an absence of anxiety, guilt, or has shallow emotions. Furthermore,<br />

some psychopaths do not fit under the ASPD diagnosis, given the heavy<br />

emphasis on illicit conduct in adolescence and adulthood. Indeed, consistent with<br />

Millon’s observations, some researchers conclude that the newest nomenclature<br />

for psychopathy (i.e., ASPD) sacrifices validity for the sake of reliability (Hare,<br />

1998).<br />

Rogers, Dion, and Lynett (1992) criticized the DSM-III and DSM-III-R criteria<br />

for the ASPD diagnosis because of its polythetic model. <strong>The</strong>se investigators contend<br />

that the minimum criteria requirement for this diagnosis is based on two inaccurate<br />

premises: (a) <strong>The</strong> criteria are not weighted; that is, no one criterion is more<br />

significant for a diagnosis than another; and (b) the frequency or severity of symptoms<br />

has no significance with regard to the diagnosis. In addition, Hart and Hare<br />

(1997) contended that “there is little systematic experimental evidence to support<br />

the validity of the DSM criteria” (p. 25).<br />

DSM-IV (1994)<br />

<strong>The</strong> objections leveled against the DSM determination of ASPD resulted in<br />

slight changes in the DSM-IV diagnosis. According to the DSM-IV (APA, 1994),<br />

ASPD “has also been referred to as psychopathy, sociopathy, or dyssocial personality<br />

disorder” (p. 645). Hare (1998) suggested that although this inclusion makes<br />

it easier for forensic psychologists or psychiatrists to discuss psychopathy in their<br />

evaluations or court testimony, greater confusion exists regarding the association<br />

between ASPD and psychopathy. Indeed, although the DSM-IV diagnosis retains<br />

the emphasis on antisocial behavior, many individuals diagnosed may not be<br />

psychopathic.<br />

In addition, the DSM-IV (1994) states that “a lack of empathy, inflated<br />

self-appraisal, and superficial charm are features that have commonly been<br />

included in the traditional conceptions of psychopathy, and may be particularly<br />

distinguishing of Antisocial Personality Disorder in prison or in forensic settings

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Confusion</strong> <strong>Over</strong> <strong>Psychopathy</strong> 339<br />

where criminal, delinquent, or aggressive acts are likely to be nonspecific”<br />

(p. 647). Hare (1998) concluded that an informal dichotomy of the ASPD criteria<br />

has been created for the community and for forensic environments, leaving the<br />

individual clinician to assess for psychopathic traits on his or her own. If a<br />

DSM-IV diagnosis is required, perhaps a diagnosis of severe ASPD with psychopathic<br />

traits should be indicated for psychopathic individuals. A more detailed<br />

discussion of diagnostic possibilities is provided in subsequent sections. For now,<br />

however, we note that changes in the DSM-IV diagnosis of psychopathy present<br />

researchers and (forensic) practitioners with additional and perplexing diagnostic<br />

problems related to ASPD.<br />

HARE’S PSYCHOPATHY CHECKLIST–REVISED<br />

Some critics of the psychopathy construct contend that a pure conceptualization<br />

of it is absent in the ASPD diagnosis, and that it is too behaviorally based, to<br />

the neglect of persistent personality traits (Hart & Hare, 1993, 1997). Hare (1998)<br />

maintained that this construct drift is the result of achieving good reliability with<br />

the ASPD diagnosis but limited validity (p. 190). Arguably, the significant reliance<br />

on behavioral criteria does not accurately measure psychopathy. This particular<br />

objection prompted Hare (1980) to develop his <strong>Psychopathy</strong> Checklist<br />

(PCL), followed by a more revised version; namely, the PCL-R (Gacono, 1998;<br />

Gacono & Hutton, 1994; Hare, 1985, 1991; Hart & Hare, 1997). Both the PCL and<br />

the PCL-R attempt to operationalize the concept of psychopathy based on the primary<br />

features of Cleckley’s (1941) original criteria. <strong>The</strong> PCL-R is a more quantifiable<br />

and semistructured interview with good reliability, validity, and norms<br />

(Hare, 1991).<br />

Hare went beyond describing the psychopath to creating a reliable and valid<br />

way to assess for psychopathy. Validity data on the PCL-R were collected from<br />

1978 to 1991 before the revised instrument was published (Hare, 2000). It was<br />

validated for male adults in forensic settings and validation studies for female<br />

adults are still in progress (Forth, 2000; Hare, 1991). In addition, global ratings of<br />

the disorder were created based on clinical observations (Hare, 1998).<br />

<strong>The</strong> PCL-R is a 20-item instrument that is on a 0-to-40-point scale (Hare, 1991;<br />

Hart & Hare, 1993). A cutoff of 30 is used for research purposes and, due to the<br />

standard error of measurement, a cutoff of 33 is suggested for clinical practice to<br />

reduce the chance of making diagnostic mistakes, particularly with forensic clients<br />

(Hare, 1991). <strong>The</strong> PCL-R approaches psychopathy from a two-factor perspective.<br />

All but 3 of the 20 items load on one of the two factors.<br />

Factor 1 represents interactional/emotional style and has been described as<br />

aggressive narcissism (Meloy, 1988). Items that load on Factor 1 are more indicative<br />

of personality traits, including, among others, (1) glibness and superficial<br />

charm, (2) grandiose sense of self-worth, (4) pathological lying, (5) conning/<br />

manipulative, (6) lack of remorse, (7) shallow affect, (8) callous lack of empathy,<br />

and (16) failure to accept responsibility for one’s own actions (Hare, 1991).

340 International Journal of Offender <strong>The</strong>rapy and Comparative Criminology<br />

Factor 2 items address behaviors or behavioral styles common to psychopaths,<br />

including, among others, (3) proneness to boredom, (9) parasitic lifestyle, (10)<br />

poor behavioral controls, (12) early behavioral problems, (13) lack of realistic<br />

long-term goals, (14) impulsivity, (15) irresponsibility, (18) juvenile delinquency,<br />

(19) revocation of conditional release (Hare, 1991). Whereas Factor 1 items<br />

remain relatively stable over time, Factor 2 items can diminish with age (Hare,<br />

1996). Additionally, in Hare (1996), only Factor 2 items have any correlation with<br />

the DSM-IV’s ASPD diagnosis.<br />

Both interviews with the participant and collateral data are recommended for<br />

the most accurate assessment. However, some researchers have used collateral<br />

data only (e.g., Harris, Rice, & Quinsey, 1991). This approach limits the evaluator’s<br />

ability to assess for glibness and superficial charm as well as many other Factor<br />

1 personality traits (Hare, 2000). In addition, collateral data is mandatory for a<br />

valid assessment of psychopathy (Hare, 1991). <strong>The</strong> instrument uses a 3-point rating<br />

scale (0, 1, 2) for each item that is based on observation of interactional style,<br />

assessing consistency of lifestyle, personality traits, and behavior, and historical<br />

information (Forth, 2000; Hare, 1991). <strong>The</strong> interview covers education, employment,<br />

family, interpersonal relationships, and both adolescent and antisocial<br />

behaviors. <strong>The</strong> interview portion of the assessment can range from approximately<br />

90 to 120 minutes. Additionally, reviewing the collateral data can take anywhere<br />

from 20 minutes to 2 to 3 hours (Forth, 2000; Hare, 1991). Whereas the DSM-IV<br />

includes the ASPD diagnosis, PCL-R scores are used to determine specifically<br />

whether an individual is psychopathic.<br />

Interestingly, many of the items that make up the PCL-R can be identified in<br />

Prichard’s (1873/1973) description of the morally insane. As Prichard commented,<br />

<strong>The</strong> individual follows the bent of his inclinations; he is continually engaging in new<br />

pursuits, and soon relinquishing them without any other inducement than mere<br />

caprice and fickleness. At length the total perversion of his affections, the dislike,<br />

and perhaps even enmity, manifested toward his dearest friends, excite greater<br />

alarm. . . . Persons labouring under this disorder are capable of reasoning or supporting<br />

an argument upon any subject within their sphere of knowledge that may be presented<br />

to them; and they often display great ingenuity in giving reasons for the<br />

eccentricities of their conduct, and in accounting for and justifying the state of moral<br />

feeling under which they appear to exist. (p. 21)<br />

We note that Item 3 (need for stimulation/proneness to boredom), Item 4<br />

(pathological lying), Item 5 (conning/manipulative), Item 8 (callous/lack of empathy),<br />

Item 10 (poor behavioral controls), Item 13 (lack of realistic long-term<br />

goals), Item 14 (impulsivity), and Item 15 (irresponsibility) can all be inferred<br />

from the observations of Prichard.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Confusion</strong> <strong>Over</strong> <strong>Psychopathy</strong> 341<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

This article traced the development of psychopathy from its historical context<br />

to its modern-day (mis)use. An analytical review of the literature demonstrated<br />

the moral, personality, and social deviance components of the disorder. To help<br />

clarify much of the diagnostic confusion surrounding this construct, the<br />

ASPD/psychopathy continuum was discussed.<br />

From its earliest conception to its present-day manifestation, psychopathy has<br />

spawned enormous debate. <strong>The</strong> controversy has encompassed such wide-ranging<br />

concerns as the morality of the individual and whether the psychopath’s actions<br />

are volitional. One of the most strongly contested elements of the diagnosis is<br />

whether these mentally disordered individuals should be socially condemned.<br />

Although it appears that psychopathy has remained, more or less, a pejorative<br />

label, the most recent debate entails the use of more behavioral criteria rather than<br />

personality traits to diagnose effectively the psychiatric illness. Notwithstanding<br />

its evolution, two features of this mental disorder have remained relatively stable<br />

and constant. First, strong reality contact or the lack of psychosis is an essential<br />

criterion for the existence of psychopathy. Second, psychopathic individuals,<br />

overall, are considered untreatable. As such, some researchers have debated the<br />

fate of psychopaths in asylums or prisons, but most agree their dispositions are<br />

largely unchangeable.<br />

Given the foregoing historical analysis, it remains to be seen what the range of<br />

present-day correctional and psychological practice implications are for psychopaths.<br />

Evaluation, diagnosis/treatment, and courtroom testimony issues are particularly<br />

worth noting. <strong>The</strong>se matters require greater research attention and explanation.<br />

This is the focus of the second article in our two-part series on the<br />

confusion over psychopathy.<br />

NOTE<br />

1. Although missing from the historical analysis, it is worth mentioning a few contributions developed<br />

by the Italian physician Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909). Lombroso was interested in how certain<br />

“inferior” physical characteristics detected in people (e.g., asymmetry of the face, large jaw and<br />

cheekbones, deviations in head size and shape) could be traced to criminals (Lombroso, 1889). Moreover,<br />

in his later theoretical reformulations, Lombroso extended his insights beyond physiological and<br />

anthropological determinants of crime causation. His typology of born criminals, insane criminals,<br />

and criminaloids is particularly useful for understanding the psychopath. Although he did not<br />

expressly describe this psychological condition, he did identify criminaloids as individuals “whose<br />

mental and emotional makeup was such that under certain circumstances they indulge[d] in vicious<br />

and criminal behavior” (Vold, Bernard, & Snipes, 1998, p. 34). Lombroso’s insights, although in some<br />

ways indirectly felt, were to have an impact on subsequent studies interpreting criminal behavior,<br />

including psychopathy.

342 International Journal of Offender <strong>The</strong>rapy and Comparative Criminology<br />

REFERENCES<br />

American Psychiatric Association. (1952). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders.<br />

Washington, DC: Author.<br />

American Psychiatric Association. (1968). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders<br />

(Rev. ed.). Washington, DC: Author.<br />

American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd<br />

ed.). Washington, DC: Author.<br />

American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders<br />

(Rev. ed.). Washington, DC: Author.<br />

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th<br />

ed.). Washington, DC: Author.<br />

Cleckley, H. (1941). <strong>The</strong> mask of sanity (1st ed.). St. Louis, MO: C. V. Mosby.<br />

Cleckley, H. (1964). <strong>The</strong> mask of sanity (5th ed.). St. Louis, MO: C. V. Mosby.<br />

Cleckley, H. (1976). <strong>The</strong> mask of sanity. St. Louis, MO: C. V. Mosby.<br />

Cleckley, H. (1982). <strong>The</strong> mask of sanity (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: C. V. Mosby.<br />

Coid, J. W. (1998). <strong>The</strong> management of dangerous psychopaths in prison. In T. Milolon, E. Simonsen,<br />

M. Birket-Smith, & R. D. Davis (Eds.), <strong>Psychopathy</strong>: Antisocial, criminal, and violent behavior<br />

(pp. 431-457). New York: Guilford.<br />

Craft, M. (1966). Psychopathic disorders and their assessment. Oxford, UK: Pergamon.<br />

Davies, W., & Feldman, P. (1981). <strong>The</strong> diagnosis of psychopathy by forensic specialists. British Journal<br />

of Psychiatry, 138, 329-331.<br />

Dinges, N. G., Atlis, M. M., & Vincent, G. M. (1998). Cross-cultural perspectives on antisocial behavior.<br />

In D. M. Stoff, J. Breiling, & J. D. Maser (Eds.), Handbook of antisocial behavior (pp. 463-473).<br />

New York: Wiley.<br />

Ellard, J. (1988). <strong>The</strong> history and present status of moral insanity. Australian and New Zealand Journal<br />

of Psychiatry, 22, 383-389.<br />

Forth, A. E. (2000, January 5-7). Assessing psychopathy with the PCL-R. Sinclair Seminars, San<br />

Diego, CA.<br />

Gacono, C. B. (1998). <strong>The</strong> use of the psychopathy checklist-revised (PCL-R) and the Rorschach in<br />

treatment planning with antisocial personality disordered patients. International Journal of<br />

Offender and Comparative Criminology, 42, 49-64.<br />

Gacono, C. B., & Hutton, H. E. (1994). Suggestions for the clinical and forensic use of the Hare <strong>Psychopathy</strong><br />

Checklist-Revised (PCL-R). International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 17(3),<br />

303-317.<br />

Gunn, J. (1998). <strong>Psychopathy</strong>: An elusive concept with moral overtones. In T. Millon, E. Simonsen,<br />

M. Birket-Smith, & R. D. Davis (Eds.), <strong>Psychopathy</strong>: Antisocial, criminal, and violent behavior<br />

(pp. 32-39). New York: Guilford.<br />

Hare, R. D. (1980). A research scale for the assessment of psychopathy in criminal populations. Personality<br />

and Individual Differences, 1, 111-119.<br />

Hare, R. D. (1985). Comparison of procedures for the assessment of psychopathy. Journal of Consulting<br />

and Clinical Psychology, 53, 7-16.<br />

Hare, R. D. (1991). <strong>The</strong> Hare <strong>Psychopathy</strong> Checklist-Revised. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health<br />

Systems.<br />

Hare, R. D. (1993). Without conscience: <strong>The</strong> disturbing world of the psychopaths among us. New<br />

York: Guilford.<br />

Hare, R. D. (1996). <strong>Psychopathy</strong>: A clinical construct whose time has come. Criminal Justice and<br />

Behavior, 23(1), 25-54.<br />

Hare, R. D. (1998). Psychopaths and their nature: Implications for the mental health and criminal justice<br />

systems. In T. Millon, E. Simonsen, M. Birket-Smith, & R. D. Davis (Eds.), <strong>Psychopathy</strong>:<br />

Antisocial, criminal, and violent behavior (pp. 188-212). New York: Guilford.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Confusion</strong> <strong>Over</strong> <strong>Psychopathy</strong> 343<br />

Hare, R. D. (2000, January 5-7). Assessing psychopathy with the PCL-R. Sinclair Seminars, San<br />

Diego, CA.<br />

Harris, G. T., Rice, M. E., & Quinsey, V. L. (1991). <strong>Psychopathy</strong> and the DSM-IV criteria for antisocial<br />

personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(3), 391-398.<br />

Hart, S., & Hare, R. D. (1993). <strong>Psychopathy</strong>, mental disorder, and crime. In S. Hodgins (Ed.), Mental<br />

disorder and crime (pp. 104-115). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.<br />

Hart, S. D., & Hare, R. D. (1997). <strong>Psychopathy</strong>: Assessment and association with criminal conduct. In<br />

D. M. Stoff, J. Breiling, & J. D. Maser (Eds.), Handbook of antisocial behavior (pp. 22-35). New<br />

York: Wiley.<br />

Koch, J. L. (1891). Die psychopathischen Mindwertigkeiten. Ravensburg, Germany.<br />

Kraepelin, E. (1915). Psychiatrie: Ein lehrbuch (8th ed., Vol. 4). Leipzig, Germany: Barth.<br />

Krafft-Ebing, R. von. (1904). Textbook of insanity (C. G. Chaddock, Trans.). Philadelphia: F. A. Davis.<br />

Lombroso, C. (1889). L’uomo delinquente [<strong>The</strong> criminal man] (4th ed.). Torino, Italy: Bocca.<br />

Lykken, D. T. (1995). <strong>The</strong> antisocial personalities. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.<br />

Martens, W. (2000). Antisocial and psychopathic disorders: Causes, course, and remission: A Review<br />

article. International Journal of Offender <strong>The</strong>rapy and Comparative Criminology, 44(3).<br />

Maudsley, H. (1897/1977). Responsibility in mental disease. New York: Publications of America.<br />

McCord, W., & McCord, J. (1964). <strong>The</strong> psychopath: An essay on the criminal mind. Princeton, NJ:<br />

Van Nostrand.<br />

Meloy, J. R. (1988). <strong>The</strong> psychopathic mind: Origins, dynamics, and treatment. Northvale, NJ: Jason<br />

Aronson.<br />

Meloy, J. R. (1996). <strong>The</strong> dangerous psychopath [Cassette Recording Vol. 25 No. 1]. Audio Digest<br />

Foundation, Psychiatry.<br />

Millon, T. (1981). Disorders of personality DSM III Axis II. New York: Wiley.<br />

Millon, T., Simonsen, E., & Birket-Smith, M. (1998). <strong>Historical</strong> conceptions of psychopathy in the<br />

United States and Europe. In T. Millon, E. Simonsen, M. Birket-Smith, & R. D. Davis (Eds.), <strong>Psychopathy</strong>:<br />

Antisocial, criminal, and violent behavior (pp. 3-31). New York: Guilford.<br />

Ogloff, J., Wong, S., & Greenwood, A. (1990). Treating criminal psychopaths in a therapeutic community<br />

program. Behavior Sciences and the Law, 8, 81-90.<br />

Pinel, P. (1962). A treatise on insanity (D. Davis, Trans.). New York: Hafner. (Original work published<br />

in 1801)<br />

Prichard, J. C. (1835). A treatise on insanity and other disorders affecting the mind. London:<br />

Sherwood, Gilbert, & Piper.<br />

Prichard, J. C. (1837/1973). A treatise on insanity and other disorders affecting the mind. New York:<br />

Arno.<br />

Rice, M. E. (1997). Violent offender research and implications for the criminal justice system. American<br />

Psychologist, 52(4), 414-423.<br />

Rice, M. E., Harris, G. T., & Cormier, C. A. (1992). An evaluation of a maximum security therapeutic<br />

community for psychopaths and other mentally disordered offenders. Law and Human Behavior,<br />

16, 399-412.<br />

Robins, L. N. (1978). Aetiological implications in studies of childhood histories relating to antisocial<br />

personality. In R. D. Hare & D. Schalling (Eds.), Psychopathic behavior: Approaches to research.<br />

Chichester, UK: Wiley.<br />

Rogers, R., Dion, K. L., & Lynett, E. (1992). Diagnostic validity of antisocial personality disorder.<br />

Law and Human Behavior, 16, 677-689.<br />

Rush, B. (1812). Medical inquiries and observations upon the diseases of the mind. Philadelphia:<br />

Kimber & Richardson.<br />

Schneider, K. (1958). Psychopathic personalities. London: Cassell.<br />

Serin, R. C. (1991). <strong>Psychopathy</strong> and violence in criminals. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 6,<br />

423-431.<br />

Simon, L. M. (1998). Does criminal offender treatment work? Applied & Preventative Psychology, 7,<br />

137-159.

344 International Journal of Offender <strong>The</strong>rapy and Comparative Criminology<br />

Smith, R. J. (1978). Personality and psychopathology: A series of monographs, texts, and treatises.<br />

New York: Academic Press.<br />

Stevens, G. F. (1993). Applying the diagnosis Antisocial Personality to imprisoned offenders. Journal<br />

of Offender Rehabilitation, 19(1/2), 1-26.<br />

Stevens, G. F. (1994). Prison clinicians’ perceptions of Antisocial Personality Disorder as a formal<br />

diagnosis. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 20(3/4), 159-185.<br />

Toch, H. (1998). <strong>Psychopathy</strong> or Antisocial Personality Disorder in forensic settings. In T. Millon,<br />

E. Simonsen, M. Birket-Smith, & R. D. Davis (Eds.), <strong>Psychopathy</strong>: Antisocial, criminal, and violent<br />

behavior (pp. 144-158). New York: Guilford.<br />

Vold, G. B., Bernard, T. J., & Snipes, J. B. (1998). <strong>The</strong>oretical criminology (4th ed.). New York:<br />

Oxford University Press.<br />

Widom, C. S. (1998). Child abuse, neglect, and witnessing violence. In D. M. Stoff, J. Breiling, & J. D.<br />

Maser (Eds.), Handbook of antisocial behavior (pp. 159-170). New York: Wiley.<br />

Zanarini, M. C., & Gunderson, J. G. (1998). Differential diagnosis of antisocial and borderline personality<br />

disorders. In D. M. Stoff, J. Breiling, & J. D. Maser (Eds.), Handbook of antisocial behavior<br />

(pp. 83-91). New York: Wiley.<br />

Zinger, I., & Forth, A. E. (1998). <strong>Psychopathy</strong> and Canadian criminal proceedings: <strong>The</strong> potential for<br />

human rights. Canadian Journal of Criminology, 40, 237-276.<br />

Bruce A. Arrigo, Ph.D.<br />

Professor and Chair<br />

Criminal Justice Department<br />

University of North Carolina–Charlotte<br />

9201 University City Boulevard<br />

Charlotte, NC 28223<br />

USA<br />

Stacey Shipley, M.A.<br />

Milwaukee County Mental Health Complex<br />

Milwaukee, WI 53204<br />

USA