4 - California Historical Society

4 - California Historical Society

4 - California Historical Society

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

california history<br />

volume 87 number 4 2010<br />

The Journal of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

Executive Director<br />

DaviD Crosson<br />

Editor<br />

JanET FirEMan<br />

Managing Editor<br />

shElly KalE<br />

Reviews Editor<br />

JaMEs J. raWls<br />

Spotlight Editor<br />

JonaThan spaulDing<br />

Design/Production<br />

sanDy bEll<br />

Editorial Consultants<br />

LARRY E . BURGESS<br />

ROBERT W . CHERNY<br />

JAMES N . GREGORY<br />

JUDSON A . GRENIER<br />

ROBERT V . HINE<br />

LANE R . HIRABAYASHI<br />

LAWRENCE J . JELINEK<br />

PAUL J . KARLSTROM<br />

R . JEFFREY LUSTIG<br />

SALLY M . MILLER<br />

GEORGE H . PHILLIPS<br />

LEONARD PITT<br />

<strong>California</strong> History is printed in<br />

Los Angeles by Delta Graphics.<br />

Editorial offices and support for<br />

<strong>California</strong> History are provided by<br />

Loyola Marymount University,<br />

Los Angeles.<br />

california history<br />

volume 87 number 4 2010 The Journal of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

c o n t e n t s<br />

From the Editor: Something in the Soil . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2<br />

Collections . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3<br />

<strong>California</strong> Legacies: James D . Houston, <strong>California</strong>n . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6<br />

By Forrest G. Robinson<br />

Sidebar: Farewell to Manzanar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17<br />

Luther Burbank’s Spineless Cactus:<br />

Boom Times in the <strong>California</strong> Desert . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26<br />

By Jane S. Smith<br />

A Life Remembered: The Voice and Passions of<br />

Feminist Writer and Community Activist Flora Kimball . . . . . . . . 48<br />

By Matthew Nye<br />

Notes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66<br />

Reviews . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72<br />

Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80<br />

Donors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84<br />

Spotlight . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88<br />

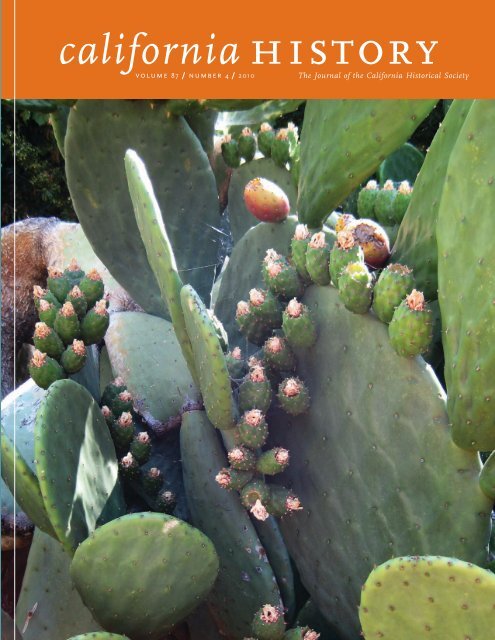

on the front cover<br />

Spineless cactus at the Luther Burbank Home &<br />

Gardens, Santa Rosa<br />

Famed plant breeder Luther Burbank “has shown<br />

us the way to new continents, new forms of life, new<br />

sources of wealth,” declared <strong>California</strong> Governor<br />

George C. Pardee in 1905. When Burbank offered his<br />

new spineless cactus for public sale in 1907, after more<br />

than twenty years of experimentation, it was instantly<br />

hailed as a miracle crop that would transform desert<br />

ranching. Jane S. Smith reveals the little known but<br />

fascinating “race to riches” story of the spineless cactus<br />

craze in her essay, “Luther Burbank’s Spineless Cactus:<br />

Boom Times in the <strong>California</strong> Desert.”<br />

Photograph by photojournalist Debra Lee<br />

Baldwin, author of Designing with Succulents<br />

(Timber Press); www.debraleebaldwin.com<br />

1

2<br />

CALIFORNIA HISTORY, September 2010<br />

Published quarterly © 2010 by <strong>California</strong><br />

<strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

LC 75-640289/ISSN 0162-2897<br />

$40.00 of each membership is designated<br />

for <strong>California</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong> membership<br />

services, including the subscription to <strong>California</strong><br />

History.<br />

KNOWN OFFICE OF PUBLICATION:<br />

<strong>California</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

Attn: Janet Fireman<br />

Loyola Marymount University<br />

One LMU Drive<br />

Los Angeles, CA 90045-2659<br />

ADMINISTRATIVE HEADQUARTERS/<br />

NORTH BAKER RESEARCH LIBRARY<br />

678 Mission Street<br />

San Francisco, <strong>California</strong> 94105-4014<br />

Contact: 415.357.1848<br />

Facsimile: 415.357.1850<br />

Bookstore: 415.357.1860<br />

Website: www.californiahistoricalsociety.org<br />

Periodicals Postage Paid at Los Angeles,<br />

<strong>California</strong>, and at additional mailing offices.<br />

POSTMASTER<br />

Send address changes to:<br />

<strong>California</strong> History CHS<br />

678 Mission Street<br />

San Francisco, CA 94105-4014<br />

THE CALIFORNIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY is a<br />

statewide membership-based organization designated<br />

by the Legislature as the state historical<br />

society. The <strong>California</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong> inspires<br />

and empowers <strong>California</strong>ns to make the past a<br />

meaningful part of their contemporary lives. In<br />

support of this mission, CHS respects and incorporates<br />

the multiple perspectives, stories, and<br />

experiences of <strong>California</strong>; acts as a respon sible<br />

steward of historical resources within its care;<br />

supports the work of other historical organizations<br />

throughout the state; fosters and disseminates<br />

scholarship to the broadest audi ences; and<br />

ensures that <strong>California</strong> history is integrated fully<br />

into the social studies curricula at all levels.<br />

A quarterly journal published by CHS since 1922,<br />

<strong>California</strong> History features articles by leading<br />

scholars and writers focusing on the heritage<br />

of <strong>California</strong> and the West from pre-Columbian<br />

to modern times. Illustrated articles, pictorial<br />

essays, and book reviews examine the ongoing<br />

dialogue between the past and the present.<br />

Articles appearing in this journal are abstracted<br />

and indexed in <strong>Historical</strong> Abstracts and America:<br />

History and Life. The <strong>Society</strong> assumes no<br />

responsibility for statements or opinions of the<br />

authors . MANUSCRIPTS for publication and<br />

editorial correspondence should be sent to<br />

Janet Fireman, Editor, <strong>California</strong> History, History<br />

Department, Loyola Marymount University,<br />

One LMU Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90045-8415,<br />

or jfireman@lmu.edu. BOOKS FOR REVIEW<br />

should be sent to James Rawls, Reviews Editor,<br />

<strong>California</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong>, 678 Mission Street,<br />

San Francisco, CA 94105-4014 .<br />

<strong>California</strong> historical society<br />

www.californiahistoricalsociety.org<br />

f r o m t h e e d i t o r<br />

soMEThing in ThE soil<br />

What produces a writer who, grounded so deeply in his native state, rousingly<br />

evoked the heights and depths of his characters’ hearts and souls commensurate<br />

with powerful portrayals of lofty mountains and the arc of the ocean waves?<br />

What nurtures the quirky genius of a New England immigrant whose imagination<br />

and unique skill in plant breeding were so productive and innovative that<br />

he was heralded by scientists and poets alike: “a unique, great genius” (the<br />

botanist Hugo De Vries) and “the man who is helping God make the earth more<br />

beautiful” (the poet Joaquin Miller)?<br />

What yields the steadfastness of an isolated, rural woman who promoted radical<br />

ideas about women’s suffrage and financial independence, persevering and<br />

finally translating her commitments into effective civic activism, including<br />

becoming the first woman in the country elected Master of a chapter of the<br />

Grange, the influential farmers’ movement?<br />

For each of these extraordinarily creative and gifted individuals, <strong>California</strong> provided<br />

the challenge, environment, and inspiration to carve a distinctive niche<br />

and establish varying degrees of recognition and status in their own times.<br />

In this issue, Forrest G. Robinson sketches the life and labor of an author whose<br />

novels and nonfiction works replicated and memorialized his beloved <strong>California</strong><br />

and his adopted second home of Hawaii. With “James D. Houston, <strong>California</strong>n,”<br />

Robinson delineates Houston’s status as a <strong>California</strong> Legacy.<br />

Jane S. Smith’s “Luther Burbank’s Spineless Cactus: Boom Times in the <strong>California</strong><br />

Desert” is a witty telling of a fascinating experiment. With narrative as<br />

smooth as the spineless paddles of the un-prickled pear (Opuntia) cactus that<br />

the Wizard of Santa Rosa bred, Smith unveils the ingredients of the spineless<br />

cactus craze—an agricultural bubble based on practicality, greed, science, and<br />

Burbank’s own deliberate quest for fame, all generated by his development of<br />

countless horicultural feats.<br />

Matthew Nye brings to light for the first time “A Life Remembered: The Voice<br />

and Passions of Feminist Writer and Community Activist Flora Kimball.” Educator,<br />

writer, and influential advocate of equal suffrage for women, Kimball was a<br />

founder, with her husband and his brothers, of National City. Through her writings<br />

in the statewide Grange publication, the <strong>California</strong> Patron, she left a permanent<br />

record of her position on the equality of women, surely representative of<br />

thousands of her silent contemporaries.<br />

What spurred the exceptional accomplishments of Houston, Burbank, and Kimball?<br />

Could it have been something in the soil?<br />

Janet Fireman<br />

<strong>California</strong> History • volume 87 number 4 2010

c o l l e c t i o n s<br />

Ex Libris<br />

(From the Library of . . .)<br />

The bookplates of hundreds of individuals<br />

and organizations in CHS’s<br />

Kemble Collections on Western<br />

Printing and Publishing are part of a<br />

long-standing tradition. Beginning in<br />

the fourteenth century, when books<br />

were rare, book owners glued decorative<br />

labels to the inside covers of their<br />

books to safeguard their possessions.<br />

As the popularity of bookplates soared<br />

between 1890 and 1940, the number<br />

of collectors in the United States grew<br />

to about 5,000. The CHS bookplate<br />

collection, which merges literature<br />

with art and typography, preserves this<br />

time-honored hobby and confirms its<br />

appeal. Its example can only hint at the<br />

satisfaction that comes from knowing<br />

a book’s provenance and its owner’s<br />

interests.<br />

After the 1950s, perhaps due to the<br />

introduction of the paperback book,<br />

William A. Brewer Collection of <strong>California</strong> Bookplates,<br />

Kemble Collections on Western Printing and Publishing<br />

bookplate production nearly disappeared.<br />

Today, with the advent of electronic<br />

book-readers, many people may<br />

never even know about, much less<br />

use them.<br />

The accompanying plates reveal varieties<br />

of self-expression and styles of art,<br />

as well as individual attitudes toward<br />

book ownership—from a sketch club’s<br />

warning to “Drink deep or taste not” to<br />

the claim, illustrated by bookplate artist<br />

Franklin Bittner, that “Dog on it, this is<br />

my Book.”<br />

3

c o l l e c t i o n s<br />

4 <strong>California</strong> History • volume 87 number 4 2010

6<br />

c a l i f o r n i a l e g a c i e s<br />

James D. Houston, <strong>California</strong>n<br />

By Forrest G. Robinson<br />

James D. Houston, known to his friends as<br />

Jim, placed a high value on order, stability,<br />

continuity, permanence. He spent virtually<br />

all of his adult life married to the same<br />

woman, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston; they lived<br />

together and raised three children in the same<br />

old house in Santa Cruz, a coastal town tucked<br />

into the northwestern end of Monterey Bay,<br />

about an hour and a half south of San Francisco<br />

on scenic Highway 1. The town—itself pretty old,<br />

as such things go in this region—is famous for<br />

its redwoods, its surfing, and its branch of the<br />

University of <strong>California</strong>.<br />

Jim loved northern <strong>California</strong>—the land, the<br />

history, the culture—and he especially loved<br />

the beautiful setting and slow-paced, unpretentious<br />

style of life in the seaside town that he and<br />

Jeanne made their home. It was here that Jim,<br />

over a period of nearly half a century, established<br />

himself as a writer, a musician, a teacher, a very<br />

visible and valued member of the local community,<br />

and a beloved friend to many. When he and<br />

Jeanne first moved to Santa Cruz in 1962, Jim<br />

recalled in a recent interview, “We both agreed<br />

<strong>California</strong> History • volume 87 number 4 2010<br />

we wanted to live here. . . . There was no lucrative<br />

job calling us. It wasn’t about professional advantage.<br />

Something about the locale itself had an<br />

appeal that turned out to be very strengthening.<br />

You might say I was sticking close to my natural<br />

habitat.” 1<br />

Jim was born in San Francisco in 1933. His parents<br />

were newcomers to <strong>California</strong>, recent arrivals<br />

from Texas who joined the Depression-era<br />

migration west in search of a better life. They<br />

weren’t disappointed. The family moved only<br />

once more, just a short distance south to the<br />

Santa Clara Valley, where they put down roots.<br />

After finishing high school, Jim completed a<br />

B.A., studying drama at nearby San Jose State<br />

University. Here he met Jeanne Wakatsuki, the<br />

daughter of Japanese immigrants who were living<br />

in the area. They were married in Honolulu<br />

in 1957, then moved to England where Jim completed<br />

a three-year tour as an information officer<br />

with a tactical fighter-bomber wing of the U.S.<br />

Air Force. The young couple traveled extensively<br />

in Europe before returning to northern <strong>California</strong><br />

and to a course of study leading to an M.A. in<br />

American Literature at Stanford University.

Alfred Russel Wallace<br />

Naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–<br />

1913) is considered by many the codiscoverer,<br />

with Charles Darwin, of the theory of natural<br />

selection. During his 1886–87 lecture<br />

tour in America, Wallace explained the principles<br />

of evolution to American audiences<br />

from Boston to San Francisco. Later, his<br />

lectures were published in his signature work<br />

on that subject, Darwinism (1889). Among<br />

the noted individuals he met in <strong>California</strong><br />

was pioneer environmentalist John Muir,<br />

to whom he presented this studio portrait,<br />

made in San Francisco, with a note of “kind<br />

remembrances” on the back.<br />

John Muir Papers, Holt-Atherton Special<br />

Collections, University of the Pacific Library;<br />

copyright 1984 Muir-Hanna Trust<br />

“Few writers have more consistently addressed the<br />

enduring issues arising out of the <strong>California</strong> experience,”<br />

wrote Kevin Starr about James D. Houston<br />

(1933–2009). Finding inspiration in the state’s natural<br />

environment, history, and culture, and empathizing<br />

with the human emotions they produced, Houston<br />

contributed to the <strong>California</strong> literary landscape with<br />

eight novels, numerous essays, and nonfiction books.<br />

This photograph, made circa 2000 in his studio in the<br />

cupola of his historic Santa Cruz home, provides an<br />

intimate glimpse of the man and his work: standing up<br />

to write, with drafts of pages displayed on a clothesline<br />

running across the length of his desk.<br />

Courtesy of Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston;<br />

photograph by Thomas Becker<br />

7

8<br />

c a l i f o r n i a l e g a c i e s<br />

Once settled in Santa Cruz, just an hour’s drive<br />

away, Jim returned to Stanford in 1966, this<br />

time as a fellow in the celebrated creative writing<br />

program directed by Wallace Stegner, who was a<br />

valued mentor and enduring influence. Jim supported<br />

his growing family and bought time for<br />

writing by teaching classical and folk guitar and<br />

playing bass in a local piano bar. His first book,<br />

Surfing: The Sport of Hawaiian Kings, which he coauthored<br />

with Ben R. Finney and which reflected<br />

his strong attraction to Hawaiian culture,<br />

appeared in 1966. A teaching stint at Stanford<br />

coincided with the publication of his first novel,<br />

Between Battles, in 1968. Teaching on a more<br />

permanent footing commenced at the new Santa<br />

Cruz campus of the University of <strong>California</strong> in<br />

1969. A second novel, Gig, winner of the Joseph<br />

Henry Jackson Award for Fiction—presented by<br />

the San Francisco Foundation as an encouragement<br />

to new writers—and dedicated “with special<br />

thanks to Wallace Stegner,” appeared in the<br />

same year. Jim’s career as a full-time professional<br />

writer was now well launched.<br />

It is probably impossible to overstate the importance<br />

of place—of northern <strong>California</strong> and the<br />

wide Pacific region it embraces—in Jim’s life<br />

and work. “By place,” he has written, “I don’t<br />

mean simply names and points of interest and<br />

identified on a map.” Rather, it is “the relationship<br />

between a locale and the lives lived there,<br />

the relationship between terrain and the feelings<br />

it can call out of us, the way a certain place can<br />

provide us with grounding, location, meaning,<br />

can bear upon the dreams we dream, can sometimes<br />

shape our view of history.” 2<br />

Drawn directly from Jim’s personal experience,<br />

this credo for literature and life took reinforcement<br />

from his teacher Wallace Stegner’s emphasis<br />

on a western “geography of hope” and echoes<br />

the views of his contemporary and friend Kevin<br />

Starr, preeminent chronicler of the <strong>California</strong><br />

Dream. Jim’s earliest published writing may<br />

appear, in retrospect, to be journeyman work in<br />

<strong>California</strong> History • volume 87 number 4 2010<br />

which he perfected his technical skills and at the<br />

same time sharpened his focus on the specific<br />

place, culture, and themes that came, in time,<br />

to define his literary identity as a modern realist<br />

and historical novelist of <strong>California</strong> and the<br />

Pacific Rim.<br />

Early WorK<br />

Surfing is an enthusiast’s overview of all aspects<br />

of the sport, with special attention to its antiquity<br />

and to its decline during the century of foreign<br />

incursions to the Hawaiian Islands culminating<br />

in the American takeover in 1898. This<br />

“tragedy,” which robbed the Hawaiians of their<br />

social, economic, and political independence,<br />

was accompanied by a sharp decline in the native<br />

population and in traditional religious beliefs and<br />

cultural practices. Against this grave background,<br />

Houston welcomes the twentieth-century revival<br />

of surfing, which spread from Waikiki Beach in<br />

Honolulu to the coast of <strong>California</strong>, and more<br />

widely after World War II to coastal sites around<br />

the world. Much of the wonder of the old Hawaiian<br />

order was lost forever. But the renewal and<br />

flourishing of this ancient sporting institution—<br />

complete with “clubs, championships, commercial<br />

importance, mountainous waves to generate<br />

modern myths, and worldwide romantic symbolism”<br />

3 —is the source of evident gratification to<br />

a lover of natural beauty, sunshine, the sea, and<br />

time-tested expressions of human pleasure and<br />

solidarity.<br />

Between Battles draws on another major dimension<br />

in Jim’s early life, his military service on<br />

an American air base in England. Though set<br />

in the historical period “between battles” of the<br />

late 1950s, the novel was written and published<br />

a decade later, as the Vietnam War escalated. It is<br />

everywhere alive to the comedy of incompetence<br />

and waste and tedium of military life. Some of its<br />

best writing surfaces in brief, wonderfully imagined<br />

takes on the all-too-human actors in a peacetime<br />

army. There is the colonel who “resembled

Houston began writing in the Air Force while stationed in Britain, publishing his first story in 1959 in the London<br />

literary journal Gemini. Another early work won a U.S. Air Force short story contest. In this photograph from 1959,<br />

he and his new wife, Jeanne, look out the window of Hillcrest, their thatched-roof cottage in Finchingfield.<br />

Courtesy of Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston<br />

9

10<br />

c a l i f o r n i a l e g a c i e s<br />

Orson Welles trying to imitate Curtis LeMay” and<br />

“Staff Sgt. Hart, a serious little man from Nevada,<br />

with the neck and face of a surprised turkey.” 4<br />

But with an obvious eye to the much more consequential<br />

realities of Vietnam, the novel offers<br />

itself as a cautionary tale about how good people<br />

can get caught up in the darkly seductive allure<br />

of modern warfare. Don Stillwell, a pilot whose<br />

plan to become an architect is cut short by a fatal<br />

crash, admits just before the book’s end that his<br />

military career has been “entirely senseless.”<br />

He is “sickened” by the thought of “training for<br />

years just to learn more efficient ways to destroy<br />

installations and cities with nuclear weapons,”<br />

and looks forward instead to learning “how to<br />

build cities” for the future. Stillwell’s message is<br />

not lost on the novel’s narrator, Lieutenant Sam<br />

Young, a college graduate and fledgling writer<br />

from <strong>California</strong> clearly modeled on the novelist<br />

himself. Traveling across England by train after<br />

his discharge, he surveys the “thatched rooves<br />

and tangled lanes and steeples poking over every<br />

country knoll” and reflects that “this world had<br />

often beguiled me. I too was drawn to things<br />

that lasted.” 5<br />

Jim’s third book and second novel, Gig, is the<br />

first actually set in northern <strong>California</strong>. Written<br />

during the year of his Wallace Stegner Creative<br />

Writing Fellowship at Stanford, Gig draws<br />

directly on Jim’s experiences as the bass player<br />

in a combo playing at a fashionable Santa Cruz<br />

restaurant. The novel’s narrator and protagonist,<br />

Roy Ambrose, confines his story to the events of a<br />

single evening at the lounge where he entertains<br />

a large handful of patrons who gather to drink<br />

and socialize around his piano. Attentive in an<br />

evidently self-conscious way to the classical unities<br />

of time, place, and action, the narrative has a<br />

partial focus in what Roy describes as his “invisible<br />

iron maiden,” 6 the fear that he will somehow<br />

fail as an entertainer and lose his audience.<br />

<strong>California</strong> History • volume 87 number 4 2010<br />

Along with occasional traces of then fashionable<br />

existentialism, the novel demonstrates signs<br />

of impatience with the smug conservatism of<br />

American middle-class life in the late 1960s, a<br />

time when “spending is the ultimate act of faith”<br />

and people “are dying of complacency and too<br />

much food.” 7 Though well written and lively in<br />

its pacing, it is a rather slender performance, and<br />

feels at times like a linked sequence of literary<br />

exercises in plot management, characterization,<br />

and dialogue.<br />

Though none of these early books fully anticipates<br />

the more important work that would soon<br />

follow, viewed in the aggregate, Surfing, Between<br />

Battles, and Gig display many of the most prominent<br />

elements in that later writing. The key<br />

locations—Santa Cruz, northern <strong>California</strong>, and<br />

Hawaii—are all featured. So are many of the key<br />

players: young people, musicians, Hawaiians,<br />

surfers. There is the emphasis that would endure<br />

on ordinary people following their dreams in<br />

search of the good life as it is frequently imagined<br />

and sometimes realized in the golden West.<br />

hisToriCal QuEsTs For ThE<br />

CaliFornia DrEaM<br />

It was clear from the start that Jim’s writing<br />

would draw heavily on his own experience, and<br />

that it would form itself into realistic, often<br />

redemptive narratives strong on tolerance,<br />

humor, pleasure, and peace. Much of this would<br />

find expression in his favorite music, which<br />

figures prominently both in the lives of his characters<br />

and in the themes that dominate their<br />

stories. Indeed, Jim was aware from early on that<br />

music was definitive in his life, as a form of pleasure,<br />

as a profession, and as a range of preferred<br />

styles and techniques that situated him in time.<br />

Though he began to emerge as a novelist of note<br />

during the era of the Beatles and rock and roll,<br />

Jim’s tastes ran to a wide array of earlier musical<br />

forms—the Hawaiian slack-key guitar and “Okie”

Houston’s passion for music nurtured his writing and revealed his individuality. His Santa Cruz bluegrass band, the Red Mountain<br />

Boys—shown here walking in an open field on the University of <strong>California</strong>, Santa Cruz campus circa 1972—was a popular<br />

mainstay of the area’s music scene: (left to right) Jim Houston, Ron Litowski, Marsh Leiceter, Kent Taylor, and Page Stegner.<br />

Courtesy of Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston<br />

songs that his father loved, traditional bluegrass,<br />

and the popular tunes, show music, and big-band<br />

sound that Gig’s Roy Ambrose claims for people<br />

of his own generation, “whose tastes and images<br />

were mainly shaped during the thirties and forties.”<br />

Jim was certainly attuned to and supportive<br />

of the forward-looking ideals of young people in<br />

the 1960s and 1970s, but his musical tastes were<br />

part and parcel with his attraction to the values<br />

and lifestyles of ordinary people in an earlier, less<br />

sophisticated America. As Ambrose goes on to<br />

observe of his generation, we “are afflicted with<br />

nostalgia and constantly look for ways to bring<br />

our past into the present.” 8 The fictional narrator<br />

speaks clearly here for his maker, a novelist alive<br />

to the lessons of history and to the great value of<br />

“things that lasted.”<br />

Published just two years after Gig, A Native Son of<br />

the Golden West is a more ambitious installment<br />

on the theme of historical continuities. The novel<br />

is longer, formally more sophisticated, and more<br />

elaborate in matters of plot and characterization<br />

than anything that Jim previously had written.<br />

Hooper Dunlap, a young, footloose surfer from<br />

southern <strong>California</strong>, quits college and migrates<br />

to Hawaii, where he hopes to satisfy his yearning<br />

for adventure—which he defines quite vaguely<br />

as “something improbable we can take real<br />

pride in.” 9<br />

Hooper’s character and quest are variations on<br />

a Dunlap family tradition, represented in the<br />

narrative by a series of flashbacks to generations<br />

of forebearers migrating from Great Britain to<br />

the United States in the eighteenth century and<br />

crossing the continent to <strong>California</strong> in the twentieth.<br />

But Dunlap habits of mobility are in tension<br />

for the young protagonist with the values of his<br />

father, a hardworking Christian fundamentalist<br />

11

12<br />

c a l i f o r n i a l e g a c i e s<br />

who has put down roots in <strong>California</strong>. In taking<br />

flight to Hawaii, Hooper has rejected religious<br />

rectitude and domestic stability for a life of aimless,<br />

sun-drenched self-indulgence in surfing,<br />

sex, booze, and music. His role model and adoptive<br />

father figure in Honolulu is Jackson Broome,<br />

an aging vagabond who owns the condemned<br />

boardinghouse where Hooper takes up temporary<br />

residence. They recognize their kinship almost<br />

immediately. “Whenever that Hooper comes in<br />

here,” Broome declares, “he makes me want<br />

to cry. He’s so much like me at that age, I can’t<br />

hardly stand it. Not much idea what he wants to<br />

do. Just out here farting around. The way all of<br />

us wish we could do all our lives. Matter of what<br />

you can get away with. I’ve always thought that<br />

was the main aim of damn near every man I’ve<br />

ever run across, to fart around as much as possible.<br />

Sooner or later a woman’ll come along,<br />

though, and throw you off course.” 10<br />

The old man proves prophetic; indeed, the<br />

woman who comes along to throw Hooper off<br />

course is Broome’s niece, Nona, a beautiful<br />

young dancer who works at a hotel near the<br />

boardinghouse. She is soon pregnant, and looks<br />

to Hooper for commitments to herself, their<br />

child, and a responsible future. But he is indecisive.<br />

This is not what he had in mind when he<br />

left <strong>California</strong>. Events accelerate toward a crisis.<br />

Broome dies suddenly of a heart attack; Hooper<br />

and a friend transport his body in a sailboat out<br />

to sea for burial. But will he decide to go back<br />

for Nona? That question goes unanswered when<br />

Hooper is killed in a careless accident. The novel<br />

closes nearly two decades later, as his son leaves<br />

<strong>California</strong> on his own.<br />

Like father, like son. And yet in seeming to<br />

affirm Hooper’s legacy, A Native Son of the<br />

Golden West represents the young man’s dream<br />

of carefree wandering in a decidedly critical<br />

light. Though a talented and attractive character,<br />

Hooper is emotionally immature; he takes what<br />

he wants from others, but shares little of him-<br />

<strong>California</strong> History • volume 87 number 4 2010<br />

self in return. “I keep getting the feeling,” Nona<br />

complains, “that you don’t care about me.” 11 Her<br />

concerns are well founded. Hooper is enthralled<br />

by an image of himself engaged in endless new<br />

beginnings—new places, new people, new experiences,<br />

with little that is constant save sunshine,<br />

music, sexual conquest, and the regularity of<br />

change itself.<br />

We can be sure that Jim Houston had a more<br />

than passing familiarity with his young protagonist’s<br />

ideas about the good life. The proof is in<br />

the energy and plausibility of his writing about<br />

those ideas. But where Hooper succumbed in his<br />

early twenties to the consequences of his own<br />

carelessness, the rising novelist in his late thirties<br />

was preparing to settle down in one place<br />

with a wife and growing family. Cast in this light,<br />

A Native Son of the Golden West may be read as<br />

a meditation on two versions of the <strong>California</strong><br />

dream, one of youthful indulgence in variety and<br />

change, the other of mature dedication to growth,<br />

continuity, and permanence.<br />

Jim’s ambivalence about accelerating change in<br />

<strong>California</strong> takes humorous expression in The<br />

Adventures of Charlie Bates, first published in 1973<br />

and reissued in slightly modified form as Gasoline<br />

in 1980. The slender volume is a gathering<br />

of seven darkly comical stories unified around<br />

the eponymous hero and his love/hate relationship<br />

with the modern automobile. In the course<br />

of his adventures, Charlie runs through several<br />

cars, as many fascinating females, several nearly<br />

global traffic jams and earth-shaking collisions,<br />

right into the madhouse. Cars are potently seductive—fast,<br />

liberating, fun. But they are also the<br />

chrome-plated symptoms—internally combustible<br />

metal monsters roaring at breakneck speed<br />

through toxic fumes on endless miles of concrete<br />

over hubcaps and tailpipes and humans and<br />

other debris—of accelerating social lunacy. One<br />

of society’s children, Charlie is literally car crazy.

The stories trace the gradual deepening of<br />

Charlie’s derangement. The first, “Gas Mask,”<br />

finds him at the numb stage. Ingenuous, utterly<br />

uncritical, he views a weeklong traffic jam as an<br />

interesting diversion. Charlie and his wife, Fay,<br />

pack sandwiches and a thermos, rent an apartment<br />

near the freeway, and calmly survey the<br />

spectacle through a pair of navy binoculars. After<br />

all, Charlie reflects, “this was really the only civilized<br />

way to behave.” But as one story succeeds<br />

another, Charlie’s world becomes more chaotic<br />

and absurd. Against a background of squealing<br />

tires, collapsing bumpers, and the hiss of steam<br />

from twisted radiators, baffled motorists try in<br />

vain to find their way. “Hey, what the hell’s going<br />

on around here!” 12 cries a red-faced man lost on<br />

the fifty-fifth floor of a hundred-story parking<br />

tower. There are no answers. The wreckage simply<br />

continues to pile up as more and more people<br />

disappear under it.<br />

Charlie survives, but only by retreating into a<br />

world of fantasy. The final story, “The Odyssey<br />

of Charlie Bates,” opens to the cacophony of a<br />

multicar collision outside a freeway tunnel. Bolting<br />

from what remains of his car, Charlie runs<br />

into Antonia, a fetching astrology freak. Together<br />

they wander into the tunnel, where hundreds of<br />

frenzied accident victims surrender to their animal<br />

urges. Naked bodies writhe; a mad bomber<br />

threatens; soldiers join in with guns and clubs.<br />

Reaching the far end of the long, narrowing tunnel,<br />

Charlie next teams up with Fanny, a vendor<br />

of griddle cakes. In a fanciful rebirth, they emerge<br />

from the darkness into a pre-automotive world of<br />

banjo bands and bicycles built for two. The only<br />

answer to the madness of the present, it appears,<br />

is nostalgic retreat to an imagined, idyllic past.<br />

Jim’s next novel emphatically confirms that his<br />

imaginative treatment of the <strong>California</strong> dream<br />

runs readily and frequently to nightmare. Published<br />

in 1978, Continental Drift is the first of<br />

three novels centrally concerned with the lives<br />

and mingled fortunes of the Doyle family. The<br />

book’s title refers to the massive fault line that<br />

runs like original sin right down the spine of<br />

<strong>California</strong>, always there, below the surface of<br />

the action, ready to unleash destruction. It cuts<br />

across the west side of the inherited, northern<br />

<strong>California</strong> family ranch of Monty Doyle and<br />

serves as a constant reminder that the dream of<br />

human possibility in this Pacific outpost of paradise<br />

is extremely fragile, just one major upheaval<br />

away from disintegration.<br />

Jim’s writing is more confident than ever in<br />

Continental Drift, probably the best of the three<br />

volumes in the Doyle trilogy. It is a very complicated<br />

narrative, with lots of twists and turns<br />

through multiple strands and perspectives deftly<br />

coordinated to produce a maximum of suspense.<br />

In many of its episodes, and in its pervasive tone<br />

of imminent catastrophe, the novel is strongly<br />

reminiscent of the period and place in which it<br />

is set, Santa Cruz in the 1970s, with its backdrop<br />

of war, generational conflict, drugs, cults, and<br />

ghastly serial murders. “You ever get the feeling<br />

that everybody in the whole wide world is going<br />

nuts?” asks Monty’s older son, Grover. “It’s more<br />

than a feeling,” his father replies; “I get an absolute<br />

certainty.” 13<br />

Geological instability is the natural correlative to<br />

major disturbances in the local community as<br />

they play themselves out in the Doyle family. In<br />

the broadest historical terms, such troubles are<br />

linked to those of all the fortune seekers who<br />

have come to <strong>California</strong>, “dreaming of conquest,<br />

dreaming of ranches . . . unending waves of<br />

explorers, wizards, gypsies, visionaries, conquistadors,<br />

people who want to take what is here and<br />

turn it into something else.” 14<br />

Closer to home, tremors run through the family<br />

in waves of marital infidelity, sibling rivalry,<br />

and the bitter harvest of war. Monty’s younger<br />

son, Travis, is just back from a tour of duty in<br />

Vietnam, an experience that has left him physically<br />

and emotionally handicapped. He places<br />

the blame for his suffering on his father, “the old<br />

13

14<br />

Santa Cruz’s 1894 courthouse—renamed the Cooper House in the 1960s and destroyed by the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake—was<br />

the scene for this 1973 assemblage of members of the Santa Cruz literary community: (windows, left to right) Morton Marcus,<br />

Peter S. Beagle, Anne Steinhardt, Robert Lundquist, James B. Hall, Steve Levine, Victor Perera, T. Mike Walker; (standing, left<br />

to right) James D. Houston, William Everson, Mason Smith; (seated, left to right) John Deck, Lou Mathews, Nels Hanson,<br />

George Hitchcock.<br />

Courtesy of Gary Griggs<br />

conquistador” who now deeply regrets having “let<br />

his son be crippled fighting another country’s<br />

wars.” It hardly helps that Monty lusts after Crystal,<br />

the pretty but promiscuous girl that Travis<br />

has brought home with him. She is a potent<br />

reminder of old fractures in Monty’s marriage to<br />

Leona, his wife of many years and the intuitive,<br />

morally grounded center of gravity in the entire<br />

trilogy. Leona is attentive to the movements<br />

of Pele, the Hawaiian volcano goddess, and to<br />

ominous turbulence around the dread “ring of<br />

fire” that encircles the Pacific Rim. The times<br />

are out of joint. Globally, nationally, locally, and<br />

right at home, Leona is witness to linked portents<br />

of an “apocalyptic turning point in the near or<br />

distant future.” 15<br />

<strong>California</strong> History • volume 87 number 4 2010<br />

The domestic drama at the center of Continental<br />

Drift intersects with a gripping murder mystery<br />

that Monty—who is a journalist when he is<br />

not tending to the ranch—follows closely and<br />

finally helps to solve. It will not do to spoil the<br />

pleasure of future readers by summarizing the<br />

plot. Suffice it to say that the unraveling of the<br />

mystery brings the members of the Doyle family<br />

through a painful crisis to subsequent stages of<br />

clarification and real, if incomplete, resolution.<br />

The earthquake of their recent lives is restored<br />

to calm and sanity at the Tassajara hot springs, a<br />

remote Zen Buddhist retreat in the Ventana Wilderness<br />

east of Big Sur. Here, at novel’s end, the<br />

Doyles rediscover what they love about <strong>California</strong>,<br />

the health and wholeness and union with nature<br />

that generously compensate for its faults. Travis

makes the trip but draws back from the reunited<br />

family once they have arrived in order to explore<br />

the healing potential of Zen spirituality. We have<br />

not heard the last of his troubles.<br />

Jim returned to the Doyle saga with Love Life,<br />

published in 1985. It is a novel true to its title,<br />

mixing roughly equal parts of family drama,<br />

soul-searching dialogue, sex, whiskey, country<br />

music, and the mysterious tides of fate, all set<br />

in and around the family ranch in northern<br />

<strong>California</strong>. The domestic crisis is played out this<br />

time against a background of biblical flood reminiscent<br />

of the punitive deluge that swamped the<br />

region in the winter of 1981.<br />

In a strikingly formal departure, Jim elected to<br />

tell his story in the first-person voice of Holly<br />

Doyle, the thirty-two-year-old wife of Monty and<br />

Leona’s older son, Grover. He succeeds admirably<br />

in creating a narrative around topics and in a<br />

tone that will strike many as distinctively “feminine.”<br />

Indeed, Love Life comes closer than anything<br />

else Jim wrote to being a popular romance.<br />

It is all about the trials and tribulations—some<br />

serious, some decidedly humorous—of sexually<br />

liberated modern love. The narrative is set<br />

in motion by Grover’s infidelity. There is no<br />

little attention to women’s liberation, to selfactualization,<br />

and to sexual experiment. “There<br />

is a male within the female,” Grover insists,<br />

“and there is a female within the male. Until you<br />

are in touch with that, you are only living half<br />

a life.” As if to acknowledge that her story tilts<br />

rather perilously toward pulp melodrama, Holly<br />

tells her friend Maureen that “we were all acting<br />

like those people you hear about on the jukebox.<br />

No matter how hard you try, sooner or later<br />

you end up somewhere inside a country-andwestern<br />

song.” 16<br />

The natural fury unleashed by the storm of<br />

Grover’s betrayal brings ordinary life to a standstill,<br />

and forces Holly and Grover into a week<br />

of isolation on their remote homestead. There,<br />

threatened by mudslides and on limited supplies,<br />

but thanks to the sage counsel of Leona and the<br />

lubricating influence of alcohol, they come to<br />

terms with some hard truths about themselves<br />

and their marriage. Down to earth and completely<br />

honest, Leona admits that she has made<br />

mistakes in raising her sons but nonetheless<br />

brings Holly to the recognition that her own<br />

doubts and fears have been major obstacles to the<br />

success of her marriage to Grover. Leona is more<br />

bluntly open with her son. “Mothers always know<br />

what’s going on,” she warns, but only as the<br />

prelude to a tearful outpouring of maternal love.<br />

Strengthened inwardly by his mother’s display of<br />

support, Grover comes in time to recognize that<br />

his own disabling fear of losing control has been<br />

an impediment to the fruition of his relationship<br />

with Holly. The storm has passed, and the novel<br />

ends, as Jim’s novels tend to, with a renewal of<br />

clarity and with real, if measured, affirmations<br />

of home, family, continuity, and the informing<br />

influence of place. Fittingly enough, Hank Williams<br />

has what amounts to the last word: “I can’t<br />

help it if I’m still in love with you.” 17<br />

The final volume in the Doyle trilogy, The Last<br />

Paradise, appeared in 1998. Like Continental Drift,<br />

it is a mystery novel, this time with a discernibly<br />

noir plot and tone. And like both of its predecessors,<br />

it follows a love story through multiple<br />

complications to a crisis and final resolution. The<br />

action of the novel has moved to Hawaii, though<br />

ties with northern <strong>California</strong> are clearly maintained,<br />

and there are constant reminders of geological,<br />

historical, and cultural continuities within<br />

the region defined by the Pacific Rim. Nature is<br />

again one of the principal dramatis personae,<br />

this time as the molten “ring of fire” encircling<br />

the entire Pacific and locally manifest in Pele, the<br />

mythological goddess of volcanoes, said to reside<br />

in the Halemaumau Crater at the summit of<br />

Kilauea volcano on the Big Island of Hawaii. Like<br />

the earthquakes and storms in the earlier novels,<br />

Pele is a force to be reckoned with, chastening<br />

foolish humans when they wander from the path<br />

of natural goodness.<br />

15

16<br />

c a l i f o r n i a l e g a c i e s<br />

Travis Doyle, last seen seeking the truth at Tassajara,<br />

is now thirty-two years old and still lost.<br />

His marriage is on the rocks, and he is an insurance<br />

claims adjuster on assignment in Hawaii,<br />

where a mainland company drilling for geothermal<br />

energy is locked in conflict with the local<br />

Hawaiians, who have had enough of outsiders<br />

exploiting and desecrating their sacred homeland.<br />

Travis has a special affinity for the Pacific.<br />

As his mother, Leona, later reveals to him, his<br />

“touch point” in life, the place of his conception,<br />

was right on the fault line. For a long time, she<br />

believed that “his years of restlessness and roaming”<br />

were directly linked to the fact that he was<br />

“a natural-born son of earthquake country.” But<br />

events persuade her that “we have been looking<br />

in the wrong place” for explanations. Instead<br />

of looking back to their ranch on the fault line,<br />

poised “to break loose at any moment and float<br />

away,” they should “look straight ahead and think<br />

about this ring, this rim we are on. . . . Aren’t we<br />

on the edge of some great big wheel here?” 18 As it<br />

turns out, Travis’s business trip to Hawaii is the<br />

beginning of a spiritual journey toward the hub of<br />

that wheel, the volcanic Pacific Rim, where he will<br />

discover his rightful place and people.<br />

It is entirely consistent with Leona’s prophetic<br />

emphasis on hidden continuities that Travis’s<br />

future should centrally involve a woman who<br />

emerges out of his past. He first met Evangeline—his<br />

destined evangelist and literary descendant<br />

of the heroine of Longfellow’s famous<br />

poem—during a visit to Hawaii when he was just<br />

sixteen. While their fathers paid their respects at<br />

the national monument at Pearl Harbor, Travis<br />

and Evangeline commenced a passionate eightweek<br />

romance that lived on in his consciousness,<br />

not in words or remembered images but as “a<br />

globe of honey-colored light.” 19 Now, two decades<br />

later, they are fatefully reunited at a time of crisis<br />

in which their rekindled love nearly succumbs to<br />

the torque of competing affiliations.<br />

<strong>California</strong> History • volume 87 number 4 2010<br />

In time, however, Evangeline converts Travis to<br />

the teachings of Pele and enlists his support in<br />

the struggle to protect the native environment<br />

from the depredations of the mainland developers.<br />

Like Travis, Evangeline is a child of fire,<br />

having been baptized by her native Hawaiian<br />

great-grandmother in the name of Pele. In bringing<br />

Travis to the fire goddess, she restores him to<br />

his natal spirituality, and thus reaffirms the special<br />

force of the love that first drew them together.<br />

At novel’s end, Travis returns to <strong>California</strong>, leaving<br />

Evangeline, who is pregnant with their child,<br />

temporarily behind. But we feel that their future<br />

as a couple is secure, aligned as it is with traditional<br />

spirituality and grounded in primordial<br />

continuities linking remote ancestors with the<br />

children of tomorrow. “The mind forgets” such<br />

things, Evangeline reflects, “but the body can<br />

remember and hear that oldest calling.” 20<br />

farewell to Manzanar anD<br />

nonFiCTion WorKs<br />

In the course of his long, extremely productive<br />

career as a professional writer, Jim earned wide<br />

recognition as a regional novelist of the first<br />

rank. But he also made stellar contributions to<br />

the field of nonfiction. Most notably, perhaps, he<br />

worked together with his wife, Jeanne, in composing<br />

Farewell to Manzanar, the autobiographical<br />

narrative of her childhood years in a World<br />

War II Japanese American internment camp in<br />

the Owens Valley. First published in 1972—and<br />

adapted for a two-hour television production in<br />

1976—the memoir broke important new historical<br />

ground and quickly established itself as<br />

a staple in high school and university courses<br />

across the country.<br />

Jim and Jeanne teamed up again in the singlevolume<br />

1985 publication that combined her<br />

Beyond Manzanar: Views of Asian American<br />

Womanhood with his One Can Think About Life<br />

After the Fish Is in the Canoe, and Other Coastal<br />

ConTinUeD on P. 20

Farewell to Manzanar<br />

In the early 1970s, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston began<br />

to recall long-suppressed memories of her family’s<br />

exile in an internment camp in Owens Valley during<br />

World War II. These encounters with her past produced a<br />

groundbreaking and compelling account of the wartime<br />

treatment of Japanese Americans, which was published<br />

in 1973 as Farewell to Manzanar. Co-authored with her<br />

husband, the book is now a <strong>California</strong> classic and standard<br />

reading in schools and colleges across the country.<br />

As James recalled in a 2007 interview, “Not long after<br />

Pearl Harbor was bombed by the Japanese military in<br />

December 1941, an entire subculture was rounded up<br />

and evacuated to ten camps, remote and godforsaken<br />

places well inland, away from the coast—120,000 people,<br />

whole families and mostly native-born American citizens,<br />

my wife among them, her nine brothers and sisters, her<br />

mother and father. The book we wrote together is her<br />

story, her family’s story. She was seven when the war<br />

started, eleven when they got out of Manzanar. Twentyfive<br />

years later we sat down in our living room here with<br />

a tape recorder and she began to voice things she’d<br />

never talked about, not with me, not with anyone.” 1<br />

Houston also spoke of his writing in the contexts of <strong>California</strong><br />

as a cultural crossroads and as a region of dreams,<br />

“the ones that come true and the ones that unravel”—<br />

themes that ring true in Farewell to Manzanar. “For me,”<br />

he acknowledged, “meeting Jeanne and her family, then<br />

working with her on Farewell to Manzanar was a huge<br />

awakening. . . . It was the beginning of an education . . .<br />

my first glimpse of another place, another way of being<br />

in this land, of a life and a history that reaches both ways<br />

across the water.” 2<br />

The following excerpts, paired with selections from the<br />

collection of Ansel Adams’s photographs of Japanese<br />

American internment at Manzanar, housed in the Library<br />

of Congress, give a personal voice to a troubled era in<br />

<strong>California</strong>’s history.<br />

—The Editors<br />

excerpts from Farewell to Manzanar by Jeanne Wakatsuki<br />

Houston and James D. Houston. Copyright © 1973 by James D.<br />

Houston. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin<br />

Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.<br />

The cover of this edition of Farewell to Manzanar, published<br />

by Houghton Mifflin Books for Children, features photographs<br />

of Jeanne and members of the Wakatsuki family during their<br />

internment, circa 1942–43.<br />

“We rode all day. By the time we reached our destination, the shades were<br />

up. It was late afternoon. The first thing I saw was a yellow swirl across<br />

a blurred, reddish setting sun. The bus was being pelted by what sounded<br />

like splattering rain. It wasn’t rain. This was my first look at something<br />

I would soon know very well, a billowing flurry of dust and sand churned<br />

up by the wind through Owens Valley.”<br />

17

“We drove past a barbed-wire fence, through a<br />

gate, and into an open space where trunks and<br />

sacks and packages had been dumped from the<br />

baggage trucks that drove out ahead of us. I could<br />

see a few tents set up, the first rows of black barracks,<br />

and beyond them, blurred by sand, rows of<br />

barracks that seemed to spread for miles across this<br />

plain.”<br />

“In Spanish, Manzanar means ‘apple orchard.’<br />

Great stretches of Owens Valley were once green<br />

with orchards and alfalfa fields. It has been a desert<br />

ever since its water started flowing south into<br />

Los Angeles. . . . But a few rows of untended pear<br />

and apple trees were still growing there when the<br />

camp opened, where a shallow water table had<br />

kept them alive. In the spring of 1943 we moved<br />

to Block 28, right up next to one of the old pear<br />

orchards. That’s where we stayed until the end of<br />

the war, and those trees stand in my memory for<br />

the turning of our life in camp, from the outrageous<br />

to the tolerable.”<br />

18 <strong>California</strong> History • volume 87 number 4 2010

“Before Manzanar, mealtime had always been<br />

the center of our family scene. In camp, and<br />

afterward, I would often recall with deep yearning<br />

the old round wooden table in our dining room<br />

in Ocean Park, the biggest piece of furniture we<br />

owned, large enough to seat twelve or thirteen of<br />

us at once. . . . Dinners were always noisy, and they<br />

were always abundant with great pots of boiled<br />

rice, platters of home-grown vegetables, fish Papa<br />

caught. . . . My own family, after three years of<br />

mess hall living, collapsed as an integrated unit.<br />

Whatever dignity or feeling of filial strength we<br />

may have known before December 1941 was lost.”<br />

“As the months at Manzanar turned to years,<br />

it became a world unto itself, with its own logic<br />

and familiar ways. In time, staying there seemed<br />

far simpler than moving once again to another,<br />

unknown place. It was as if the war were forgotten,<br />

our reason for being there forgotten. The present,<br />

the little bit of busywork you had right in front<br />

of you, became the most urgent thing. In such a<br />

narrowed world, in order to survive, you learn to<br />

contain your rage and your despair, and you try to<br />

re-create, as well as you can, your normality, some<br />

sense of things continuing.”<br />

19

c a l i f o r n i a l e g a c i e s<br />

Sketches. Jim’s very readable <strong>California</strong>ns: Searching<br />

for the Golden State, a collection of brief travel<br />

narratives featuring exchanges with such notables<br />

as Luis Valdez, Steve Jobs, and Tom Bradley,<br />

appeared in 1982. Where Light Takes Its Color<br />

from the Sea, A <strong>California</strong> Notebook, published in<br />

2008, is a kindred selection of memories and<br />

reflections highlighted by illuminating chapters<br />

on Wallace Stegner and Ray Carver.<br />

And there is more—a substantial shelf of nonfiction<br />

that stretches to include Open Field (1974),<br />

a biography of 49ers quarterback John Brodie;<br />

The Men in My Life (1987), a volume of “More or<br />

Less True Recollections of Kinship”; In the Ring of<br />

Fire (1997), the narrative of a journey through the<br />

Pacific Basin; Hawaiian Son: The Life and Music<br />

of Eddie Kamae (2004), a tribute to the legendary<br />

ukulele virtuoso; and numerous collections of<br />

West Coast writing, most notably volume 1 of The<br />

Literature of <strong>California</strong>, co-edited with Jack Hicks,<br />

Maxine Hong Kingston, and Al Young, published<br />

by the University of <strong>California</strong> Press in 2000.<br />

Snow Mountain PaSSage anD<br />

laTEr WorKs<br />

But Jim will be remembered best for his novels,<br />

the writing that most fully engaged his creative<br />

attention and talent. Doubtless the most memorable<br />

novel of them all is Snow Mountain Passage,<br />

the superb fictional re-creation of a defining<br />

chapter in <strong>California</strong> history, published to considerable<br />

acclaim in 2001. The inspiration for the<br />

novel lent great credence to Jim’s sense that the<br />

important things in life happen for a reason.<br />

After inhabiting their Santa Cruz Victorian for<br />

several decades, all the while employing its lofty<br />

cupola as his study, Jim discovered, apparently<br />

quite by chance, that Patty Reed, one of the children<br />

who survived the infamous Donner Party<br />

tragedy of 1846–47, had lived in the house until<br />

the end of her long life. Her father, James Frazier<br />

Reed, was one of the principal organizers of<br />

the ill-fated wagon train and a protagonist in the<br />

20 <strong>California</strong> History • volume 87 number 4 2010<br />

conflicted events that left the party trapped for<br />

the winter in the frozen Sierra.<br />

For a novelist interested in history, family, and<br />

continuities of time and place, and who believed,<br />

as Jim certainly did, that “old voices are always in<br />

the air, in the towns and in the soil, waiting to be<br />

heard,” this was a story he was destined to write.<br />

In “Where Does History Live?”—his essay on the<br />

novel’s fateful provenance—Jim describes his<br />

surrender to the potent attraction of the project<br />

and his sudden, startling access to the characterizing<br />

words and cadences of Patty Reed’s voice.<br />

“I would not call it an actual sound in my head,”<br />

he recalls; “nor was it the quaver of ghostly sentences<br />

rising out of shadowy cobwebs at the far<br />

side of the attic. Rather, it was the distinct sense<br />

of a certain way of remembering, a way of speaking<br />

as the elderly woman Patty Reed might have<br />

spoken in the years when she lived here, before<br />

she died in the bedroom downstairs.” It was the<br />

advent of that voice, he goes on, that “gave me a<br />

way into this novel.” 21<br />

There can be no question that Jim’s empathic<br />

ingress to Patty’s sensibility is integral to the success<br />

of Snow Mountain Passage. She is a sturdy<br />

but forgiving moralist who does not shrink from<br />

the appraisal of her father’s very consequential<br />

character flaws and errors in judgment. “I cannot<br />

excuse him,” she admits; “yet neither is it my<br />

place to judge him, as others have, or to judge<br />

the way he contended with the trials of that crossing.”<br />

Her father attracted enemies, she recalls, in<br />

her vigorous western vernacular, “like an open jar<br />

of jam will gather ants and blowflies. This cannot<br />

be denied.” 22<br />

Patty is a woman made wise before her years<br />

by the terrible events of her childhood. “By age<br />

nine,” she reflects, “I had come to see that each<br />

hour of my life was a wonder.” But we approach<br />

the deep human center of what Patty Reed has<br />

taken from her experience in the novel’s extraordinary<br />

opening, an extract from the fictional “trail<br />

notes” that Jim created as the vehicle for her

unique voice. Describing a dream in which she<br />

sees her mother, Patty writes, “She was speaking<br />

words I could not hear. I ran through the snow,<br />

while her mouth spoke the silent words. I was<br />

young, a little girl, and also the age I am now. For<br />

a long time I ran toward her with outstretched<br />

arms. Finally I was close enough to hear her soft<br />

voice say, ‘You understand that men will always<br />

leave you.’ I stopped running and in my mind<br />

called out to her, ‘No. It isn’t so!’ Her mouth<br />

twitched, as if she were about to speak again.<br />

She wanted to say, ‘Listen to me, Patty.’ She was<br />

trying to say it. I woke up then and spoke aloud.<br />

‘Women leave you too.’ I was speaking right to<br />

her, and I waited, expecting to hear her voice in<br />

my ear, as if she were close by me in the dark. I<br />

whispered, ‘Don’t you remember?’ But she was<br />

gone.” 23<br />

Too soon and too painfully for a child, that long,<br />

desperate winter in the Sierra taught Patty that<br />

there are no sure things in life, no durable stays<br />

against the sense of defenseless isolation and<br />

vulnerability that overtakes many people, usually<br />

at some later stage in their allotted time. When<br />

she needs them most—when her child’s real-<br />

Approximately half of the members of the Donner Party who were<br />

trapped in the Sierra Nevada during the deadly winter of 1846–47<br />

perished. Among those who survived, the Reed family settled in San<br />

Jose. Later, Patty Reed (1838–1923) lived in the Victorian house<br />

overlooking the East Cliff beaches of Santa Cruz that became home<br />

in 1962 to Houston and his wife, Jeanne. Patty posed for this photograph<br />

circa 1920 at the house, from which Houston envisioned her<br />

recollections of the Donner saga in Snow Mountain Passage. Following<br />

the book’s publication, Houston recalled:<br />

“I can still sit in the rocking chair Patty Reed sat in eighty-five<br />

years ago. I can look into a beveled mirror she once looked into,<br />

above the oak-paneled fireplace. From the verandah I can regard<br />

her view of Monterey Bay, which still glitters and beckons, and<br />

consider that on the day we moved in, back in 1962, her story,<br />

her family’s story, was already waiting here, inside the house.”<br />

Courtesy, History San José<br />

ity is suddenly exposed to extremes of danger,<br />

deprivation, and the grossest human degradation—both<br />

parents, responding to the necessities<br />

of the crisis, leave her to face the nightmare<br />

on her own. Mortal diminishment and panic in<br />

the face of encroaching anomie is the novel’s<br />

defining theme. Bereft “in the midst of a treeless<br />

desert,” the pioneers are “strangers again, more<br />

estranged than before they met, estranged and<br />

abandoned.” 24<br />

Unfairly judged and then banished from the<br />

wagon train, James Frazier Reed imagines himself<br />

“marooned upon the lonesome face of a<br />

far-off planet, a hundred million miles out into<br />

space, looking back upon this rolling speck, as<br />

small as the smallest pinpoint in the vault of<br />

stars.” All such images have their affective center<br />

of gravity in Patty’s shattering childhood encounter<br />

with parental betrayal at a time of crisis. “I<br />

don’t have to tell you what it felt like,” she writes,<br />

evidently confident that we will understand, “to<br />

be that age and have both your mother and your<br />

father disappear into country that seemed to have<br />

no beginning and no end.” 25<br />

21

22<br />

This photograph of Truckee Lake, where Patty Reed and sixteen other members of the Donner Party were rescued, was taken<br />

from Frémont Pass in 1868 as the Central Pacific Railroad reached completion. The areas inhabited by the emigrants became<br />

known as Donner Pass, Donner Lake, and Donner Peak. In Snow Mountain Passage, Patty observed:<br />

“When I was a girl there were no trains anywhere yet out here. When we came through the mountains there was hardly<br />

any trail. Where the train cuts through the Sierra Nevada now, we made that trail. What a long road we have traveled.”<br />

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Central Regional Library, A. J. Russell Collection<br />

Taking a cue from Grace Paley, Jim has acknowledged<br />

that in order to finish his novel he had<br />

to supplement Patty Reed’s voice with a second<br />

narrative, one which “comes rising up next to the<br />

first, or sometimes comes rising up inside it, and<br />

it’s the telling of the two together that makes the<br />

story.” This second formal and thematic ingredient<br />

integral to the success of Snow Mountain<br />

Passage is the omniscient treatment of the larger<br />

story of the star-crossed migration from Illinois,<br />

through the horrific winter in the Sierra, and<br />

down at last to the promised land in <strong>California</strong>.<br />

The featured player in this half of the drama, and<br />

the counterpoint to Patty’s “strong and contem-<br />

<strong>California</strong> History • volume 87 number 4 2010<br />

plative presence,” is her father, who embodies the<br />

“restless male urge to pull up stakes and make<br />

the headlong continental crossing.” 26<br />

Like so many others who risked the dangerous<br />

journey, James Frazier Reed comes to <strong>California</strong><br />

following a dream of a fresh start in a new<br />

land. He wants adventure and opportunities for<br />

leadership. Most of all, he looks forward to the<br />

day when his family will settle and prosper in a<br />

place of beauty and abundance, a place like the<br />

orchard land adjacent to an abandoned mission<br />

near San Jose. He covets this land as a sanctuary<br />

whose possession will answer a deep human

craving—felt most profoundly by his daughter<br />

Patty—for security, permanence, and repose. “In<br />

his mind,” Reed “sees the year turn, he sees the<br />

pruned limbs sprout new buds. He sees the pears<br />

and plums spring forth, burdening the limbs. He<br />

sees his children climbing among the branches,<br />

and scurrying between the rows to gather windfall<br />

fruit.” 27 This, surely, is something worth<br />

fighting for.<br />

But in the course of achieving his dream, Reed<br />

and his fellow pioneers help to wrest power from<br />

the resident colonials and to violently dispossess<br />

the much larger indigenous population. By the<br />

terms of conquest, security and abundance for<br />

the conquerors are the yield on terrible deracination<br />

and penury for the conquered. While her<br />

father fights valiantly for control of the territory,<br />

Patty, clinging to life in the snowbound Sierra,<br />

discovers “another hero standing in reserve. His<br />

name was Salvador.” 28 In token of his loyalty to<br />

the forsaken child, the young Indian guide gives<br />

her his adobe amulet to wear around her neck.<br />

Later on, as circumstances grow increasingly<br />

dire, poor Salvador is killed and cannibalized by<br />

other members of the party. At novel’s end, his<br />

surviving brother, Carlos, turns up at the mission<br />

orchard that the victorious Reed has now claimed<br />

as a home for his family. Carlos recognizes the<br />

amulet and demands an account of his brother’s<br />

fate. As the terrible truth spills out, Patty realizes<br />

that Salvador’s family, “the sons, the father, the<br />

mother too, a family much like ours,” had until<br />

very recently made their home on the mission<br />

orchard. Carlos gives voice to “a low groan” that<br />

The reunion of Patty and her father, James Frazier Reed, is imagined in this sketch from an 1849 account of the <strong>California</strong><br />

and Oregon territories. Through Patty’s voice in Snow Mountain Passage, Houston described James at the start of their journey—a<br />

depiction that was inevitably altered by the tragic events that followed:<br />

“He was a dreamer, as they all were then, dreaming and scheming, never content, and we were all drawn along in<br />

the wagon behind the dreamer, drawn along in the dusty wake. . . . Sometimes very early, before it gets light, I will<br />

still see him the way he looked the day we left Illinois. In his face I see true pleasure and a boyish gleam that meant<br />

his joy of life was running at the full.”<br />

J. Quinn Thornton, Oregon and <strong>California</strong> in 1848, vol. 2 (new York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1849), 196;<br />

<strong>California</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

23

24<br />

c a l i f o r n i a l e g a c i e s<br />

soon “swelled to a howling wail” of grief for his<br />

brother and for the many thousands more whose<br />

lives were destroyed by the conquest. 29<br />

In this powerfully moving denouement, Jim<br />

draws into sharpened focus the sense of imminent,<br />

retributive catastrophe that runs through<br />

his earlier novels. All those restless, conquering<br />

dreamers and adventurers and settlers are prey<br />

to the nameless, unshakable melancholy, rooted<br />

in historical guilt, which hangs over places like<br />

<strong>California</strong>, where innocent people have been<br />

made homeless so that others might claim a<br />

new place in the world. This is the deeper moral<br />

significance of those recurrent earthquakes and<br />

floods and volcanic eruptions. Patty recognizes<br />

that the faithful Salvador, truly her savior, was<br />

sacrificed to the fruition of her father’s dream of<br />

possession, continuity, and prosperity. She sees<br />

that her long, stable, abundant life has its roots<br />

in Salvador’s lonely grave. Here, then, is the<br />

source of the chastened gratitude and melancholy<br />

that run through Patty’s story. “If only we could<br />

find a way to inhabit a place without having to<br />

possess it,” she broods; “it’s possession that<br />

divides us.” 30<br />

The formal and thematic elements that combine<br />

so successfully in Snow Mountain Passage reappear<br />

in Jim’s last complete novel, Bird of Another<br />

Heaven, which was published in 2007. Sheridan<br />

Brody, a young radio talk show host in San Francisco,<br />

is unexpectedly contacted by a long-lost<br />

grandmother who puts him in touch with his<br />

remote Hawaiian and Native American roots.<br />

The theme, once again, is history, this time with<br />

a special emphasis on racial diversity and on the<br />

grave injustices wrought by nineteenth-century<br />

American expansion in <strong>California</strong> and the Hawaiian<br />

Islands. Sheridan’s program, which reaches<br />

out to a highly diverse audience, is dedicated<br />

to letting “the past speak to the present,” 31 not<br />

least of all by renewing and strengthening ties<br />

between generations.<br />

<strong>California</strong> History • volume 87 number 4 2010<br />

Locating the self in space is also important, as<br />

the novel’s leading characters scrutinize complex<br />

genealogies in order to find their proper homes<br />

in the sprawling geography of the Pacific Rim.<br />

For Nani Keala, Jim’s mixed-race great-grandmother,<br />

identity runs “deeper than ownership,<br />

deeper than boosterism or patriotism. . . . Hers<br />

was an ancestral bond rooted in bedrock not<br />

made of documents.” 32 Finally, like Snow Mountain<br />

Passage before it, Bird of Another Heaven<br />

unfolds in two narratives that run along parallel<br />

tracks toward a final, clarifying resolution.<br />

Sheridan’s story, related in the first person, is<br />

an attempted reconstruction of the mysterious<br />

events surrounding the 1891 death of the Hawaiian<br />

King Kalakaua in San Francisco’s Palace<br />

Hotel. At intervals, meanwhile, Sheridan’s greatgrandmother’s<br />

intimate role in the mystery—she<br />

was the king’s distant cousin and lover—is set<br />

forth by an omniscient narrator. The partial solution<br />

to the mystery emerges from the convergence<br />

of the two narratives at the novel’s end.<br />