Under Travelling Skies departures from Larkin - University of Hull

Under Travelling Skies departures from Larkin - University of Hull Under Travelling Skies departures from Larkin - University of Hull

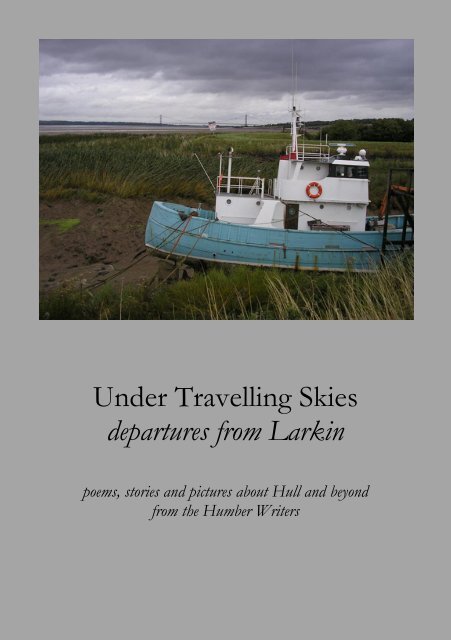

Under Travelling Skies departures from Larkin poems, stories and pictures about Hull and beyond from the Humber Writers

- Page 2 and 3: UNDER TRAVELLING SKIES Departures f

- Page 4 and 5: Contents Under Travelling Skies 6 F

- Page 6 and 7: 108 Mary Aherne Quadrille 110 David

- Page 8 and 9: Under Travelling Skies Architexts (

- Page 10 and 11: Under Travelling Skies loud complai

- Page 12 and 13: Under Travelling Skies ‘I don’t

- Page 14 and 15: Under Travelling Skies Philip Larki

- Page 16 and 17: Under Travelling Skies Larkin, who,

- Page 18 and 19: Maurice Rutherford Absences My pare

- Page 20 and 21: Cliff Forshaw Still Here This is th

- Page 22 and 23: Under Travelling Skies And all the

- Page 24 and 25: Under Travelling Skies up the road

- Page 26 and 27: House Clearance Under Travelling Sk

- Page 28 and 29: Cliff Forshaw: Humber Bridge Englis

- Page 30 and 31: Spurn Head Under Travelling Skies A

- Page 32 and 33: Under Travelling Skies and leering,

- Page 34 and 35: Under Travelling Skies Kath McKay C

- Page 36 and 37: Under Travelling Skies The session

- Page 38 and 39: Under Travelling Skies One autumn n

- Page 40 and 41: Where do the arguments of the sea e

- Page 42 and 43: above the feeble rush of the founta

- Page 44 and 45: Under Travelling Skies Malcolm Wats

- Page 46 and 47: Four-Minute Warning: Kilnsea A mons

- Page 48 and 49: Maurice Rutherford Friday ‘Friday

- Page 50 and 51: Kingston Upon Hull (A Fabled City)

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

<strong>departures</strong> <strong>from</strong> <strong>Larkin</strong><br />

poems, stories and pictures about <strong>Hull</strong> and beyond<br />

<strong>from</strong> the Humber Writers

UNDER TRAVELLING SKIES<br />

Departures <strong>from</strong> <strong>Larkin</strong><br />

edited by<br />

Cliff Forshaw<br />

Kingston Press<br />

Published with the assistance <strong>of</strong><br />

The <strong>Larkin</strong>25 Words Award<br />

and<br />

The <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong>

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

British Library Cataloguing in Publications Data.<br />

A catalogue record for this book is available <strong>from</strong> the British library.<br />

First published 2012<br />

Published by Kingston Press<br />

A <strong>Larkin</strong>25 Words Award commission.<br />

Individual poems, stories and articles © the authors unless specified.<br />

Images © John Wedgwood Clarke: pages 82, 86, 88, and 111; Cliff<br />

Forshaw: cover, all photographs and pages 27, 39, 67, 92, 105; Malcolm<br />

Watson: pages 18, 23, 26, 31, 37, 58, 75 and 102.<br />

All rights reserved. No part <strong>of</strong> this publication may be reproduced,<br />

stored in retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means,<br />

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without<br />

prior permission <strong>of</strong> the publishers.<br />

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way <strong>of</strong><br />

trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired or otherwise circulated, in any<br />

form <strong>of</strong> binding or cover other than that in which it is published,<br />

without the publisher’s prior consent.<br />

The Authors assert the moral right to be identified as the Authors <strong>of</strong> the<br />

work in accordance with the Copyright Design and Patents Act 1988.<br />

ISBN 978-1-902039-19-0<br />

Kingston Press is the publishing imprint <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> City Council Library<br />

Service,<br />

Central Library, Albion Street, <strong>Hull</strong>, England, HU1 3TF<br />

Telephone: +44 (0) 1482 210000<br />

Fax: +44 (0) 1482 616827<br />

e-mail: kingstonpress@hullcc.gov.uk<br />

www.hullcc.co.uk/kingstonpress<br />

Printed by Butler, Tanner & Dennis, Frome, Somerset, UK.<br />

2

Contents<br />

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

6 Foreword<br />

8 James Booth<br />

Far Away <strong>from</strong> Everywhere Else: <strong>Larkin</strong> and <strong>Hull</strong><br />

17 Maurice Rutherford<br />

Absences<br />

Here 2012<br />

19 Cliff Forshaw<br />

Still Here<br />

22 David Wheatley<br />

Bridge for the Dying: Dispatches <strong>from</strong> <strong>Larkin</strong>’s <strong>Hull</strong> 1<br />

26 Carol Rumens<br />

Bibliomythos<br />

English Bridges<br />

The Whitsun Awayday<br />

Spurn Head<br />

30 Malcolm Watson<br />

Philip and the Monsters<br />

Keyingham, Midwinter 1898<br />

33 Kath McKay<br />

Craters, lava plains, mountains and valleys<br />

38 Sarah Stutt<br />

Notice to Mariners<br />

Scat Singing in Pearson Park<br />

42 Christopher Reid<br />

The Clarinet<br />

43 Malcolm Watson<br />

Blues at the Black Boy<br />

Saint Helen’s Well, Great Hatfield, Holderness<br />

Four-Minute Warning: Kilnsea<br />

47 Maurice Rutherford<br />

Friday<br />

Des Res<br />

Kingston Upon <strong>Hull</strong><br />

3

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

4<br />

50 Cliff Forshaw<br />

Gone<br />

54 Carol Rumens<br />

After a Deluge<br />

Shades<br />

Almost True: A Guided Walk through <strong>Larkin</strong>’s<br />

Cottingham<br />

Reinscriptions<br />

Coats<br />

61 Kath McKay<br />

“Not Much Evidence <strong>of</strong> the Docks”<br />

Coupling<br />

Carving it up<br />

On the train Reading Philip <strong>Larkin</strong><br />

66 Mary Aherne<br />

Down in the Dumps<br />

68 Carol Rumens<br />

Squibs<br />

71 John Mowat<br />

<strong>Larkin</strong>’ About in <strong>Hull</strong><br />

His Almost Funny Valentine<br />

Snaps Like a Crocodile<br />

76 Mary Aherne<br />

A Walk Through Beverley<br />

80 David Wheatley<br />

Bridge for the Dying 2<br />

89 Kath McKay<br />

The Curtain<br />

93 John Wedgwood Clarke<br />

Wander<br />

95 Ray French<br />

Elsewhere<br />

103 Cliff Forshaw<br />

The Bohemian <strong>of</strong> Pearson Park<br />

Dead Level

108 Mary Aherne<br />

Quadrille<br />

110 David Wheatley<br />

Erosion<br />

111 Contributors’ Notes<br />

Artwork<br />

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

John Wedgwood Clarke<br />

82 Winter Sea, Cornelian Bay. Oil on canvas, 27”x 22”.<br />

86 Freighter (Ravenscar). Oil on canvas, 27”x22”.<br />

88 Fishing Gear, Scarborough Harbour, Squall . Watercolour, 7”x5”.<br />

111 Cornelian Bay (low tide). Oil on canvas. 36” x 24”.<br />

Cliff Forshaw<br />

27 Humber Bridge. Acrylic on canvas, 39” x 12”.<br />

39 Spurn Lightship. Acrylic on canvas, 32” x 40”.<br />

67 Spurn Lightship Variations. Digital image.<br />

92 Another <strong>from</strong> the Myth Kitty – <strong>Larkin</strong> Surprised by Aphrodite on the<br />

Humber. Acrylic on canvas with gold-coloured wire and shells,<br />

50” x 40”.<br />

105 Sketch for Another <strong>from</strong> the Myth Kitty – After a Bibulous Lunch,<br />

<strong>Larkin</strong> Stumbles on Some Hippies and Mistakes Them for the Retinue<br />

<strong>of</strong> Dionysus. Acrylic on canvas with wine corks, 50” x 40”.<br />

Malcolm Watson<br />

18 Look downward, Angel, down Cemetery Road. Collage on card, 11½”<br />

x 11½”.<br />

23 Cherry Cobb Sands Road, Stone Creek . Acrylic, pen and ink and<br />

coloured pencils on paper, 10½” x 14<br />

26 Shelved. Fibrepen and coloured pencils on paper, 11½ x 14½”.<br />

31 Lonelier and lonelier... and then the sea. Collage and gouache on<br />

embossed paper, 12” x 12”.<br />

37 Sunk Island Sands. Acrylic on canvas, 39¼” x 31¼.<br />

58 Complimentary/Complementary? Acrylic on Card, 11½” x 11½”.<br />

75 Inside Out. Collage on Card.,11½” x 11½”.<br />

102 Purple Haze. Graphite and gouache on embossed paper, 12”<br />

x12”.<br />

All photographs and overall design: Cliff Forshaw<br />

5

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong>: Departures <strong>from</strong> <strong>Larkin</strong><br />

Foreword<br />

The Humber Writers are a loose group <strong>of</strong> poets and fiction writers<br />

associated with the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong>. Many teach or have taught<br />

in the English Department, and Carol Rumens and Christopher<br />

Reid have both been Pr<strong>of</strong>essors <strong>of</strong> Creative Writing there. Over<br />

the years members <strong>of</strong> the group have collaborated on a number <strong>of</strong><br />

projects specifically focused on <strong>Hull</strong> and its neighbouring land-<br />

and seascapes, <strong>of</strong>ten resulting in books and performances for the<br />

Humber Mouth Literature Festival: A Case for the Word (2006);<br />

6

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

Architexts (2007); Drift (2008); Hide (2010); and Postcards <strong>from</strong> <strong>Hull</strong><br />

(2011).<br />

<strong>Larkin</strong>25 was a unique cultural programme, celebrating the<br />

life, work and legacy <strong>of</strong> the poet, novelist, librarian and jazz critic<br />

Philip <strong>Larkin</strong> twenty-five years after his death. The <strong>Larkin</strong>25<br />

Words Award continues this celebration by supporting the<br />

development <strong>of</strong> literature in <strong>Hull</strong> and the East Riding and it is a<br />

great privilege for our group to have won the first commission for<br />

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong>. It has been a pleasure editing this anthology<br />

and I would like to thank all the contributors for rising to the<br />

challenge. Here we have not only poems and stories but essay and<br />

reminiscence; we look at <strong>Larkin</strong>’s life and times in <strong>Hull</strong>, but also<br />

venture further afield to <strong>Larkin</strong>’s other haunts in Beverley, in<br />

Holderness and along the coast. We look at what those places<br />

meant to him and his contemporaries, and what they mean to us –<br />

and we hope to you − now.<br />

There are many, apart <strong>from</strong> the writers here, who have made<br />

this project and the accompanying film and exhibitions possible,<br />

and I would particularly like to thank Graham Chesters and Rick<br />

Welton and The Philip <strong>Larkin</strong> Society as a whole; John Bernasconi<br />

at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> Art Gallery and Kate Crawford and<br />

Emma Dolman at Artlink for organising the exhibitions; Charlie<br />

Cordeaux, Jo Hawksworth and Kit Hargreaves at Holme House<br />

Media Centre, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> who helped me make the film.<br />

Many thanks also to the <strong>University</strong> for its continued and generous<br />

support to the Humber Writers.<br />

Cliff Forshaw, <strong>Hull</strong>, May 2012.<br />

7

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

James Booth<br />

8<br />

Far Away <strong>from</strong> Everywhere Else: <strong>Larkin</strong> and <strong>Hull</strong><br />

Some writers celebrate the places where they were born or lived<br />

and are embraced by them. They become identified with a city, a<br />

region, a tribe, a nation: Hardy with Dorchester and Dorset,<br />

Dickens with London and the Thames ports, Dylan Thomas with<br />

Swansea and Wales, Heaney with Anahorish and Ireland. Local<br />

commercial, political and tourist interests have long been<br />

accustomed to brand their locations by appropriating a national or<br />

international figure as one <strong>of</strong> their ‘sons’. The Lake District claims<br />

Wordsworth, Stratford-on-Avon claims Shakespeare, Lichfield<br />

claims Dr Johnson. Dorcestrians feel an intimate pride that<br />

Thomas Hardy is one <strong>of</strong> their own. In contrast, when the <strong>Larkin</strong><br />

Society promoted the idea <strong>of</strong> a statue in <strong>Hull</strong> station there were

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

loud complaints that the poet was a posh southerner with no roots<br />

in the city. He wasn't born here; just listen to his accent. He got a<br />

job in <strong>Hull</strong> purely by accident. He didn’t even like <strong>Hull</strong>. Even<br />

those inhabitants <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> who are pleased that <strong>Larkin</strong> lived and<br />

worked here for so long, do not feel the tribal intimacy with him<br />

which a favoured son usually elicits.<br />

<strong>Larkin</strong> always denied that he was ‘at home’ anywhere. ‘No, I<br />

have never found / The place where I could say / This is my proper<br />

ground, / Here I shall stay…’ Rootlessness is intrinsic to his selfimage<br />

as a lyric poet. Attempts to claim him on behalf <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong>, or<br />

even <strong>of</strong> England, never quite work. One <strong>of</strong> his keynote poems,<br />

‘The Importance <strong>of</strong> Elsewhere’, written just before his move to<br />

<strong>Hull</strong>, concerns his fear <strong>of</strong> returning <strong>from</strong> the anonymous freedom<br />

<strong>of</strong> his life in Belfast, where he lived <strong>from</strong> 1950 until 1955, to the<br />

threatening responsibilities <strong>of</strong> England. He had been ‘Lonely in<br />

Ireland, since it was not home’. Nevertheless somehow<br />

‘strangeness made sense’: His existence was ‘underwritten’ by this<br />

elsewhere. In Ireland he had permission to be separate, and felt<br />

‘not unworkable’. Back ‘home’ in England, he has no excuse <strong>of</strong><br />

difference: ‘These are my customs and establishments / It would<br />

be much more serious to refuse.’ He will be forced to toe the line.<br />

It is amusing to see how Seamus Heaney misconstrues this poem:<br />

‘during his sojourn in Belfast in the late (sic) fifties, he gave thanks,<br />

by implication, for the nurture that he receives by living among his<br />

own’. Heaney’s is an organically tribal sensibility, and he imagines<br />

that <strong>Larkin</strong> must be tribal also. But <strong>Larkin</strong> had nowhere where he<br />

felt ‘nurtured’ by being among ‘his own’. Though he hated abroad<br />

in one sense, in a wider sense he is perpetually ‘abroad’ in the<br />

world.<br />

Nevertheless, anywhere is always somewhere, and ‘elsewhere’<br />

and ‘nowhere’ are lexically rooted in ‘here’. <strong>Larkin</strong> cannot avoid<br />

topography. Indeed his poems contain a select but intense<br />

gazetteer <strong>of</strong> real places. These places are, however, always first and<br />

9

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

foremost ideograms <strong>of</strong> inner states <strong>of</strong> mind, or cultural<br />

stereotypes: Coventry where his childhood was unspent, Oxford<br />

where he had to account to the Dean for ‘these incidents last<br />

night’, Dublin where afternoon mist drifts round race-guides and<br />

rosaries, Leeds, home <strong>of</strong> chain-smoking salesmen, Stoke where Mr<br />

Bleaney’s sister has her house. During his early years in <strong>Hull</strong>, when<br />

he was as he put it ‘living the life <strong>of</strong> Bleaney’, <strong>Hull</strong> became a<br />

symbol <strong>of</strong> his ‘failure’ in life. His verdict, in a letter to Monica<br />

Jones <strong>of</strong> September 1955, was damning<br />

10<br />

Dearest,<br />

Back to this dreary dump,<br />

East Riding’s dirty rump,<br />

Enough to make one jump<br />

Into the Humber –<br />

God! What a place to be:<br />

How it depresses me;<br />

Must I stay on, and see<br />

Years without number?<br />

– This verse sprang almost unthought-<strong>of</strong> <strong>from</strong> my<br />

head as the train ran into <strong>Hull</strong> just before midday. I’m<br />

sure no subsequent verse could keep up the high<br />

standard. Pigs & digs rhyme, <strong>of</strong> course, likewise work &<br />

shirk, & <strong>Hull</strong> & dull, but triple rhymes are difficult.<br />

There is something infectiously euphoric about this jaunty<br />

doggerel. Reading between the lines, he was wondering whether he<br />

might do worse than spend his life in this place. He already had a<br />

‘subsequent’ version <strong>of</strong> this glum celebration in his mind. Six years<br />

later this poem was to see the light in the form <strong>of</strong> the sumptuous<br />

and magical ‘Here’.

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

‘I don’t really notice where I live’ <strong>Larkin</strong> said in an interview,<br />

‘as long as a few simple wants are satisfied – peace, quiet, warmth<br />

– I don’t mind where I am. As for <strong>Hull</strong>, I like it because it’s so far<br />

away <strong>from</strong> everywhere else’. He effectively found his proper place<br />

when in the autumn <strong>of</strong> 1956 he rented a third storey flat at 32<br />

Pearson Park <strong>from</strong> the <strong>University</strong>. The room was reserved by the<br />

<strong>University</strong> for new members <strong>of</strong> staff while they looked around for<br />

something better. But, once he was installed, <strong>Larkin</strong> never looked<br />

further, and spent the rest <strong>of</strong> his writing life in transit. This was for<br />

him the most creative <strong>of</strong> situations: high up in a rented attic on the<br />

edge <strong>of</strong> things.<br />

So, when, five years later, in October 1961, he wrote his great<br />

poem <strong>of</strong> place, he called it not ‘<strong>Hull</strong>’, but ‘Here’. <strong>Hull</strong>, as it was in<br />

the 1950s and 1960s is a recognisable element in the poem: its<br />

ships up streets, slave museum, consulates, tattoo shops and grim<br />

head-scarved wives. Its inhabitants, a ‘cut-price crowd’, are<br />

precisely observed as they push through plate-glass doors to their<br />

desires: ‘Cheap suits, red kitchen-ware, sharp shoes, iced lollies’.<br />

But it is also aesthetically distanced: a universal ‘pastoral’, if an<br />

unorthodox ‘terminate and fishy-smelling’ one. This ‘urban, yet<br />

simple’ world has the same idyllic innocence as Theocritus’s or<br />

Virgil’s artificial visions <strong>of</strong> nymphs and shepherds. Though the<br />

ostensible medium is social realism, <strong>Larkin</strong>’s vignette <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> is<br />

also an archetype <strong>of</strong> the social existence <strong>of</strong> all readers, wherever<br />

our particular ‘here’ may be.<br />

As the poem drives towards its goal the reader becomes aware<br />

that this city- and landscape is invironment as much as<br />

environment. From beginning to end the poem is a restless quest<br />

across country, never stopping for breath until it reaches the sea.<br />

Life, the poet is aware, is an ever-moving point <strong>of</strong> consciousness;<br />

we have nothing else. Wherever we may be in a <strong>Larkin</strong> poem we<br />

are always here. Similarly, as the speaker <strong>of</strong> an early work<br />

euphorically reassures his beloved, ‘always is always now’. The<br />

11

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

largest vista in his work, the seascape in ‘Absences’ is an ‘attic’ in<br />

his head. Even more adverbially and relativistically it is an attic<br />

‘cleared <strong>of</strong>’ him. The end <strong>of</strong> ‘Here’ takes us to the same sublime<br />

place as ‘Absences’, where bluish neutral distance ends the land<br />

suddenly and we find ourselves contemplating ‘unfenced existence:<br />

/ Facing the sun, untalkative, out <strong>of</strong> reach’.<br />

Are we questing outwards, <strong>from</strong> the enclosure <strong>of</strong> a railway<br />

carriage, to the roads and shops <strong>of</strong> the town, to vast empty<br />

skyscape? Or are we questing inwards <strong>from</strong> traffic all night north<br />

through the busy social world <strong>of</strong> the city into solitude and silence?<br />

Either way, time is lost in place. There are no events; only an<br />

undated present. The clock has stopped. <strong>Larkin</strong> was aware in<br />

October 1961 that his life had reached its zenith: its central<br />

moment <strong>of</strong> balance. He had entered his fortieth year and things<br />

would never be better than this. In the workbook the poem was<br />

originally entitled ‘Withdrawing Room’, the archaic form <strong>of</strong><br />

‘drawing room’, imaging the ever-moving moment <strong>of</strong> being here as<br />

the most intimate <strong>of</strong> the rooms into which we withdraw (or which<br />

withdraw <strong>from</strong> us). Stanza is the Italian for ‘room’ (usually in the<br />

plural, stanze: a suite <strong>of</strong> rooms). In this patterned stanza-form<br />

<strong>Larkin</strong> has found a comfortable poetic withdrawing room <strong>of</strong> his<br />

own, to match his literal room in Pearson Park.<br />

As he said, <strong>Hull</strong> is far away <strong>from</strong> everywhere else; even further<br />

away in his day, when it took four or five hours to reach London<br />

by train. Like Belfast, <strong>Hull</strong> was an elsewhere which made him feel<br />

welcome by insisting on difference. Belfast had been a ferry<br />

journey away, but <strong>Hull</strong> was almost equally secluded, at the end <strong>of</strong><br />

the railway line with only the North Sea beyond. It is: ‘On the way<br />

to nowhere, as somebody once put it... Makes it harder for people<br />

to get at you... And <strong>Hull</strong> is an unpretentious place. There’s not so<br />

much crap around as there would be in London.’ Even the ‘salt<br />

rebuff’ <strong>of</strong> the Northern Irish accent is replicated in the local <strong>Hull</strong><br />

dialect which makes ‘phone’ into ‘fern’ and ‘road’ into ‘rerd’. At a<br />

12

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

Philip <strong>Larkin</strong> Society dinner held in 2010 to raise money for the<br />

erection <strong>of</strong> <strong>Larkin</strong>’s statue, Maureen Lipman stood beside a fibreglass<br />

toad in the form <strong>of</strong> Philip <strong>Larkin</strong> and declared, in her best<br />

<strong>Hull</strong> accent, that this was the first time she had ever shared the<br />

stage with a ‘turd’.<br />

‘Friday Night in the Royal Station Hotel’, written in 1966, five<br />

years after ‘Here’, shows <strong>Larkin</strong> evoking the same poetic territory<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> and Holderness. But the mood has shifted. He was now<br />

well into his forties and the warm social perspectives <strong>of</strong> his Whitsun<br />

Weddings period were being replaced by the mannered inwardness<br />

<strong>of</strong> his late style. This may be the Royal Station Hotel in <strong>Hull</strong>, but it<br />

is also a metaphorical plight, like that <strong>of</strong> Kafka or Beckett, in<br />

which we wait for our trial to begin, or for Godot to arrive. In the<br />

deserted hotel lounge, the speaker contemplates the headed paper,<br />

‘made for writing home’, and interjects in lugubrious parenthesis<br />

‘(If home existed)’. At the conclusion <strong>of</strong> the poem we withdraw<br />

inward, as in ‘Here’, in contemplation <strong>of</strong> the North Sea coast. But<br />

the sublime daylight <strong>of</strong> the earlier poem is replaced by moody<br />

crepuscular gloom: ‘Night comes on. / Waves fold behind<br />

villages.’<br />

Older and with the shades falling, <strong>Larkin</strong> took his inspiration<br />

<strong>from</strong> a more ominous <strong>Hull</strong> location. Seven years later than ‘Friday<br />

Night in the Royal Station Hotel’, in 1972, as he approached 50, he<br />

completed ‘The Building’. The opening catches an exact visual<br />

impression <strong>of</strong> the ‘lucent [honey]comb’ <strong>of</strong> the yellow-lit <strong>Hull</strong> Royal<br />

Infirmary on the Anlaby Road. But this image <strong>of</strong> a ‘cliff’ <strong>of</strong> light,<br />

surrounded by ‘close-ribbed’ streets, like ‘a great sigh out <strong>of</strong> the<br />

last century’, is also extravagantly romantic. In one <strong>of</strong> the most<br />

remarkable rhetorical coups <strong>of</strong> twentieth-century poetry dull reality<br />

becomes poetic dream as the death-bound patients are tantalised<br />

by the poignantly inaccessible vision <strong>of</strong> ‘Red brick, lagged pipes,<br />

and someone walking [...] / Out to the car park, free’. There,<br />

outside the hospital is the gorgeous normality <strong>of</strong> traffic, children<br />

13

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

playing, and, in an elegiac metonym <strong>of</strong> life as glamorous as<br />

anything in Yeats: ‘girls with hair-dos’ fetching their ‘separates<br />

<strong>from</strong> the cleaners’. Everyday things take on the glowing,<br />

inaccessible loveliness <strong>of</strong> an image on a Grecian Urn or a mythical<br />

Byzantium.<br />

In an acknowledgement <strong>of</strong> the fact that he had indeed, in his<br />

own contradictory and provisional way, found his proper ground<br />

in <strong>Hull</strong>, <strong>Larkin</strong> did, in one late poem, take upon himself the<br />

uncharacteristic role <strong>of</strong> a local spokesman. ‘Bridge for the Living’<br />

was written to a commission <strong>from</strong> the <strong>Hull</strong> construction company,<br />

Fenner, for words to a cantata marking the completion <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Humber Bridge. As one might expect, his heart was not fully in the<br />

task. He told Anthony Hedges, Reader in Composition at the<br />

<strong>University</strong>, who wrote the music, that he ‘felt more like writing a<br />

threnody for the things he loved about the region which the bridge<br />

would put an end to.’ Nevertheless the poem is a not unattractive<br />

example <strong>of</strong> the genre <strong>of</strong> the topographical poem. The words are<br />

well suited to a musical setting, and the sections (summer and<br />

winter, before the bridge and after), are easily apprehended. The<br />

register is a rhetorically heightened pastiche <strong>of</strong> ‘Here’, with<br />

elevated diction: ‘Isolate’, ‘parley’, ‘manifest’, and with fugato<br />

chiming effects: ‘Tall church-towers parley airily audible, /<br />

Howden and Beverley, Hedon and Patrington.’ The description <strong>of</strong><br />

the suspended single span <strong>of</strong> the bridge, ‘The swallow rise and fall<br />

<strong>of</strong> one plain line’, is itself, appropriately, one plain line. The poem’s<br />

ending again recalls ‘Here’. But where that poem culminated in a<br />

vision <strong>of</strong> unfenced existence, out <strong>of</strong> reach, ‘Bridge for the Living’<br />

ends by ‘reaching’ grandiosely ‘for the world’.<br />

* * *<br />

In his recently published selection <strong>of</strong> <strong>Larkin</strong>’s poems Martin Amis<br />

contrasts the life <strong>of</strong> his own father, Kingsley, who he takes to have<br />

been a true ‘bohemian’, with that <strong>of</strong> the ‘nine-to-five librarian’,<br />

14

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

<strong>Larkin</strong>, who, in his version: ‘lived for thirty years in a northern city<br />

that smelled <strong>of</strong> fish (<strong>Hull</strong> – the sister town <strong>of</strong> Grimsby).’ Here in<br />

<strong>Hull</strong>, Amis believes, <strong>Larkin</strong>, wifeless and childless, lived out a<br />

personal history <strong>of</strong> sad ‘gauntness’ with ‘no emotions, no vital<br />

essences, worth looking back on’. The aridity <strong>of</strong> his life, Amis tells<br />

us, ‘contributed to the early decline <strong>of</strong> his inspiration.’ He<br />

‘siphoned all his energy, and all his love, out <strong>of</strong> the life and into the<br />

work’; he had ‘no close friends’. Martin’s father, Kingsley Amis,<br />

had never visited <strong>Hull</strong> during the whole 30 years that <strong>Larkin</strong> lived<br />

here. Like father like son.<br />

Those who were closer to <strong>Larkin</strong> than either Amis do not<br />

recognise this version. <strong>Larkin</strong> was by all accounts an empathetic<br />

friend, an entertaining companion, and a passionate and loyal<br />

lover. He did not produce a young Kingsley <strong>Larkin</strong>, which might<br />

have s<strong>of</strong>tened Martin Amis’s verdict. But no one enjoyed ‘the<br />

million-petalled flower <strong>of</strong> / Being here’ more intensely than he,<br />

even in <strong>Hull</strong>. With his haunting sense <strong>of</strong> life as an insecure passing<br />

moment it was <strong>Larkin</strong>, not Amis, who was the true bohemian.<br />

Reading the poems tells one as much. His inspiration declined not<br />

because <strong>of</strong> sterile provincial inertia, but because he had been burnt<br />

out by the crowded intensity <strong>of</strong> his imaginative and emotional life.<br />

In 1982, three years before he died, <strong>Larkin</strong> was induced, a<br />

touch reluctantly, to write a one-page foreword to an anthology <strong>of</strong><br />

local poets, A Rumoured City: New Poets <strong>from</strong> <strong>Hull</strong>, edited by his<br />

colleague in the Library at the time, the Scottish poet, Douglas<br />

Dunn. He had now spent the best part <strong>of</strong> three decades in <strong>Hull</strong><br />

and his tone is mellow and retrospective. He revisits the<br />

conclusion <strong>of</strong> ‘Here’ for a final time, this time in a glowing prosepoem:<br />

When your train come to rest in Paragon Station<br />

against a row <strong>of</strong> docile buffers, you alight with an end<strong>of</strong>-the-line<br />

sense <strong>of</strong> freedom. Signs in foreign languages<br />

15

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

16<br />

welcome you. Outside is a working city, yet one neither<br />

clenched in the blackened grip <strong>of</strong> the industrial<br />

revolution nor hiding behind a cathedral to pretend it<br />

is York or Canterbury. Unpretentious, reticent, full <strong>of</strong><br />

shops and special <strong>of</strong>fers like a television commercial, it<br />

might be Australia or America, until you come upon<br />

Trinity House or the Dock Offices. For <strong>Hull</strong> has its<br />

own sudden elegancies.<br />

People are slow to leave it, quick to return. And there<br />

are others who come, as they think, for a year or two,<br />

and stay a lifetime, sensing that they have found a city<br />

that is in the world yet sufficiently on the edge <strong>of</strong> it to<br />

have a different resonance. Behind <strong>Hull</strong> is the plain <strong>of</strong><br />

Holderness, lonelier and lonelier, and after that the<br />

birds and lights <strong>of</strong> Spurn Head, and then the sea. One<br />

can go ten years without seeing these things, yet they<br />

are always there, giving <strong>Hull</strong> the air <strong>of</strong> having its face<br />

half-turned towards distance and silence, and what lies<br />

beyond them.<br />

Once again the topographical <strong>Hull</strong> <strong>of</strong> social realism is doubled by<br />

a more elusive <strong>Hull</strong> <strong>of</strong> the mind, on the way to nowhere, far away<br />

<strong>from</strong> everywhere else. The face <strong>of</strong> this <strong>Hull</strong> is half-turned, in airy,<br />

beautiful phrases, towards distance and silence, and what lies<br />

beyond them. And what is that, one might ask. <strong>Larkin</strong>’s<br />

relationship with the city is exactly caught by Martin Jennings’s<br />

great statue on Paragon Station. The poet rushes out <strong>of</strong> the hotel<br />

bar, larger than life, <strong>of</strong>f balance but very much alert to the here<br />

and now. He holds his manuscript under his arm and casts the<br />

dark shadow <strong>of</strong> his anxieties before him. But there ahead, a few<br />

seconds away, forever waiting for him to board, is the train which<br />

will take him <strong>from</strong> this elsewhere to the next. Always is always<br />

now.

Maurice Rutherford Absences<br />

My parents, seen through mist that brings them near,<br />

blurred grans and aunts who peopled Perth Street West,<br />

Chant’s Ave, back when … I brush away the blear:<br />

they die again, with siblings, and the best<br />

school pal I ever had at Park Street Tech.,<br />

lost wartime army mates and all the rest<br />

including those forgotten, as the wreck<br />

<strong>of</strong> self erodes my brain. Discrepancies —<br />

flawed fluency <strong>of</strong> thought — the loss <strong>of</strong> rhyme<br />

and rea… Where was I? … Ah, yes … absences …<br />

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

17

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

Here 2012<br />

Were Philip <strong>Larkin</strong> now alive<br />

there’d be, as passengers arrive<br />

by train at <strong>Hull</strong>, no sculpted Bard<br />

to greet them in the station yard,<br />

no Trail. They might instead explore<br />

a sparsely-peopled large cool store;<br />

not Toads, but more <strong>of</strong> cut-price lives,<br />

<strong>of</strong> jobless men <strong>from</strong> raw estates<br />

sustained by part-time-earning wives<br />

and hand-outs <strong>from</strong> their working mates<br />

to whom the poet’s <strong>of</strong> small account<br />

nor does his death itself amount<br />

to more than’s carved in stone. And yet<br />

this voice whose lines they can’t forget<br />

remains in town to quicken blood<br />

<strong>of</strong> folk far <strong>from</strong> <strong>Hull</strong>’s gull-marked mud<br />

who may themselves be on short-time<br />

but head for Paragon each year<br />

in thrall to what he left in rhyme,<br />

and find him, out <strong>of</strong> reach, still here.<br />

Malcolm Watson: Look downward, Angel, down Cemetery Road<br />

18

Cliff Forshaw Still Here<br />

This is the future furthest childhood saw<br />

Between long houses, under travelling skies ‘Triple Time’<br />

You’d hardly recognise some parts,<br />

though other streets would take you back<br />

between the bombers and the planners.<br />

We needed then, <strong>of</strong> course, a brand new start;<br />

those times would soon be history, we thought.<br />

The shining future was already overdue<br />

the day you lugged your case <strong>of</strong> shirts, socks, suits,<br />

books, LPs, spare specs, those Soho mags;<br />

that struggling with umbrella, flapping mac<br />

− all the impedimenta <strong>of</strong> being you.<br />

We may have lacked the phrase, but, boy, we knew,<br />

before your train stopped shy <strong>of</strong> our docile buffers,<br />

we were already ready. It was time to move on,<br />

the day you hailed that cab at Paragon.<br />

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

19

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

That waste ground in the middle distance could,<br />

just about, proclaim that brand new start.<br />

The past had gone; the future lay in wait.<br />

And now? The past clings on, and on, and on,<br />

down ten-foot and outside large cool store alike.<br />

The past is never over: it isn’t even past.<br />

And when the future finally turned up here,<br />

we felt it both too slow yet far too fast.<br />

It wasn’t what we’d seen back then, playing<br />

on waste-ground in imagined silver-suits:<br />

protein capsules, the four-hour week, jet-packs;<br />

the dreams <strong>of</strong> winged de Loreans, marinas, sex.<br />

Tomorrow’s World so suddenly vacuum-packed;<br />

now was full <strong>of</strong> nothing. So was the past.<br />

*<br />

He would have known the old dry docks,<br />

the frosted extravagance <strong>of</strong> the Punch<br />

and, a street or two behind, the plain Dutch:<br />

the miscegenation <strong>of</strong> honest-to-God austerity<br />

with municipal baroque, aldermanic<br />

fantasies <strong>of</strong> marble and mahogany,<br />

leather-upholstered, overstuffed portraits.<br />

Nostalgia, that’s Greek for ‘home’ and ‘pain’.<br />

Home is where the hearth was: is always in the past.<br />

What he thought he knew were ships up streets,<br />

but his cold northern ships, historic moons,<br />

candles, cobbles was one long false start,<br />

full <strong>of</strong> sentimental cruelty,<br />

like many a family, or ‘prentice poetry.<br />

20

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

And all the while a part <strong>of</strong> us still sits<br />

in the back seat <strong>of</strong> a half-timbered Morris Traveller<br />

or squeaks the leatherette <strong>of</strong> a Hillman Imp,<br />

is intent on the dials set in the walnut fascia<br />

or peers into the future through the broken wipers<br />

<strong>of</strong> a Jowett Javelin up on bricks in the drive<br />

− that’s us forever asking ‘Are we there yet?’<br />

Steamy Sunday windows, Bisto, mint<br />

<strong>from</strong> the allotment, dads breezing back <strong>from</strong> swift halves,<br />

the fizz <strong>of</strong> Cherryade, Family Favourites: Osnabrück,<br />

BFPO, Auntie Ethel and Uncle Ted<br />

in Alice, Sydney, or Upper Hutt, En Zed.<br />

Is this untrumpeted arrival our long-awaited destination?<br />

Are we there yet? Is this, at last, the place we dare call home?<br />

21

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

David Wheatley Bridge for the Dying 1<br />

Bubonic Plague<br />

The case <strong>of</strong> former paratrooper Christopher Alder was much in<br />

the news when I moved to <strong>Hull</strong> in 2000. He had died in police<br />

custody, and the arresting <strong>of</strong>ficers were tried for unlawful killing,<br />

allowing him to asphyxiate without coming to his aid; the case<br />

ended in an acquittal. There was a racial dimension too, with<br />

allegations <strong>of</strong> monkey noises having been made over Alder as he<br />

lay on the floor. Now eleven years later he is in the news again as<br />

we learn that the body buried under his name in Western<br />

Cemetery, on Chanterlands Avenue, is not his after all but that <strong>of</strong> a<br />

female pensioner. The possibility <strong>of</strong> an exhumation is complicated<br />

by the fact that when the plot was last opened, it was to allow the<br />

scattering <strong>of</strong> his niece’s ashes over ‘his’ c<strong>of</strong>fin. I know the<br />

cemetery well, as will anyone who has seen the 1964 Monitor film<br />

<strong>of</strong> Philip <strong>Larkin</strong> briskly cycling through it. In one overgrown<br />

corner is a mass grave for the Irish victims <strong>of</strong> a Victorian cholera<br />

epidemic, in another the elaborately inscribed headstone <strong>of</strong><br />

Captain Gravill, Captain <strong>of</strong> the Diana, the ill-fated last whaler to<br />

sail out <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong>, wrecked <strong>of</strong>f Greenland in 1866. Not far up the<br />

road is Northern Cemetery, in whose children’s section I have<br />

spent lugubrious half-hours inspecting the teddy bears and<br />

balloons. In fact, the necropolises <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> are all too well known to<br />

me: the Jewish cemeteries on St Ninian’s Walk and beside the<br />

Alexandra Hotel, the overgrown and fenced-<strong>of</strong>f plots <strong>of</strong><br />

Sculcoates, the city-margins reliquaries <strong>of</strong> Eastern Cemetery and its<br />

‘columbarium’, in which I stumbled on the grave <strong>of</strong> a bubonic<br />

plague victim, died 1916. How does a <strong>Hull</strong> teenager catch bubonic<br />

plague in 1916? A bubo is a swollen gland, but a bubo bubo is an<br />

eagle owl, that splendid creature, an example <strong>of</strong> which used to live<br />

22

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

up the road <strong>from</strong> Eastern Cemetery in the village <strong>of</strong> Paull. I<br />

imagine the complex traceries <strong>of</strong> bone that must make up eagle<br />

owl pellets. Let each bone be numbered and identified. Vole, fieldmouse,<br />

shrew. Let our remains too be mourned over according to<br />

our various rites, in our various graves: inscribed, communal,<br />

mistaken, nameless, unknown.<br />

Malcolm Watson: Cherry Cobb Sands Road , Stone Creek<br />

23

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

Purity <strong>of</strong> Heart is to Will One Thing<br />

‘Perhaps a maritime pastoral /Is the form best suited /To a<br />

northern capital’, writes Tom Paulin in ‘Purity’, <strong>from</strong> his second<br />

book The Strange Museum, a collection strongly marked by his time<br />

as an undergraduate at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong>. <strong>Hull</strong> may not be a<br />

northern capital, but when attacked in the Blitz it was referred to<br />

by the BBC, for security reasons, as ‘a Northern city’. This appears<br />

to have sown some confusion in Berlin, where Lord Haw Haw<br />

mentioned the bombing <strong>of</strong> Gilberdyke, a hamlet fifteen miles<br />

upstream, under the impression that it was in <strong>Hull</strong>. Tom Paulin has<br />

written a lot about the war, and I think <strong>of</strong> him when I find the<br />

story in Gillett and MacMahon’s History <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> (OUP, 1980) <strong>of</strong><br />

‘one public <strong>of</strong>ficial, <strong>of</strong> moderate importance, who had formed a<br />

fascist cell’ in the 1930s but withdrew to Northern Ireland when<br />

the war broke out. (With his strong views on <strong>Larkin</strong>, Paulin might<br />

be reminded <strong>of</strong> <strong>Larkin</strong>’s German-admiring father Sydney, who<br />

waited until the day war was declared to take down the Nazi regalia<br />

adorning his <strong>of</strong>fice at Coventry City Council.) Reaching<br />

pensionable age our Northern Irish refugee wrote to <strong>Hull</strong> City<br />

Council demanding his due and was told to return to <strong>Hull</strong> to<br />

collect it, the intention being to arrest and intern him. Before he<br />

could do this he was killed in Belfast by a German bomb, a turn <strong>of</strong><br />

events that may have caused him some mixed feelings in the splitsecond<br />

<strong>of</strong> his death. In more recent times, a <strong>Hull</strong> Nazi <strong>of</strong> sorts<br />

found himself in trouble with the law for distributing holocaustdenying<br />

literature, and skipped bail to the United States, where he<br />

unsuccessfully sought asylum before being deported back to prison<br />

in the UK. Paulin’s ‘Purity’ ends with a vision <strong>of</strong> a crowded<br />

troopship in the distance, ‘Its anal colours /Almost fresh in the<br />

sun’, a ‘pink blur /Of identical features’. Purity <strong>of</strong> heart is to will<br />

one thing, said Kierkegaard. There’s a lot more <strong>of</strong> it about than he<br />

suspected.<br />

24

House Clearance<br />

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

When Philip <strong>Larkin</strong> died, the house in Newland Park he shared<br />

with Monica Jones stayed just as it was in his lifetime. The brave<br />

souls (not many) who dropped in on Jones in later life have<br />

described the testing mix <strong>of</strong> odours that hung in the air, and the<br />

Miss Havishamesque creature camped amid her nests <strong>of</strong> empties<br />

and curdled Terry and June-era décor. Hundreds <strong>of</strong> <strong>Larkin</strong>’s letters<br />

lay strewn round the house, many stuffed down the back <strong>of</strong> a s<strong>of</strong>a.<br />

A sad end. When Monica died, the house was cleared. The <strong>Larkin</strong><br />

Society worked the place over, and the resulting harvest <strong>of</strong> papers<br />

went to the Bodleian. A builder was then told to empty the<br />

property. Imagine the surprise <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Larkin</strong>ites when the builder<br />

announced he had found a notebook with jottings <strong>of</strong> unpublished<br />

<strong>Larkin</strong> poems. How could this have happened? Had he removed it<br />

during Jones’ lifetime and waited until her death to stage his<br />

‘discovery’? Things got murky, <strong>of</strong>fers were made and rejected. A<br />

rare book dealer was involved. The jottings in question were<br />

largely drafts <strong>of</strong> Christmas card greetings, I was told. No matter.<br />

The builder and a rare book dealer met on a railway platform in<br />

King’s Cross and the builder returned to <strong>Hull</strong> a richer man.<br />

However, the time has come to reveal the truth. The notebook<br />

was a hoax. I planted it. I needed my gutters fixing and didn’t have<br />

the money. Preparations are already in hand for my own demise:<br />

an explosive correspondence tucked away in the sideboard, a lost<br />

novel under the sink. The house nosily feasts on these hidden<br />

treasures. I come in the front door and find it going through my<br />

filing cabinet. I let out an indignant roar. The drawer snaps shut<br />

and we agree not to speak <strong>of</strong> this further.<br />

25

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

Carol Rumens Bibliomythos<br />

To discover you, <strong>of</strong> the calm, precise mind,<br />

incarnate at the core <strong>of</strong> my obsession<br />

is to face a book that stirs, acquires a backbone,<br />

and crawls out <strong>of</strong> the water, mortal, moral,<br />

peppercorn eyes amassing strings <strong>of</strong> light-cells.<br />

Meanwhile, I’m knocked back to fishy dimness.<br />

I read as peasants read: four thought-racked fingers<br />

sweat into linenboard, left thumb defines<br />

attention-span and page-depth, right fist grinds<br />

the fiery cheek, but the gaze floats <strong>from</strong> the carrel,<br />

searching the city ro<strong>of</strong>s for lambs or samphire.<br />

Hours pass with evolutionary momentum −<br />

Then a sudden scuffle <strong>of</strong> leaves, the whip <strong>of</strong> an arrow<br />

and you, <strong>of</strong> the calm, precise mind, you, who were god-like, jump<br />

out <strong>of</strong> the undergrowth, pursued by muses −<br />

on fawn’s hooves, wearing nothing but your heart.<br />

26<br />

Malcolm Watson: Shelved

Cliff Forshaw: Humber Bridge<br />

English Bridges<br />

clasping the little girl she<br />

crouched on the safety-rail a man<br />

lost in the custody fight<br />

shudders, the crowd below<br />

the woman leapt, survived, was jailed for<br />

is howling do it do it<br />

attempted murder<br />

do it chicken do it<br />

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

27

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

The Whitsun Awayday<br />

We left at bright mid-day, and again I wondered<br />

what violence <strong>of</strong> the sun could ever bruise<br />

the sabulous and sky-denying river.<br />

I thought <strong>of</strong> all the c<strong>of</strong>fee-machines, drizzling<br />

and dripping in the renovated dockside<br />

<strong>of</strong>fices, bland talk <strong>of</strong> brand and target,<br />

lingering reek <strong>of</strong> the whale-shed, corporate stab-wounds −<br />

and the main attraction slopped across her sandbanks<br />

portside to the Transpennine Express,<br />

then retreated to a pinkish stain and sank<br />

behind the neat apologetic factories.<br />

Like Ambhas, I had made my bed, too many<br />

returning tides had smoothed the wrong conclusion,<br />

approaching now under the bridge that slowed<br />

ominously starboard. I would live here<br />

a little longer, I had always lived here,<br />

stumbling behind a heavy-drinking, scornful<br />

shade, his large, desolate footprints wandering<br />

with the old villages, patterning the night-wolds<br />

by gravitational chance.<br />

Was he consoled,<br />

too, thinking about the quicker, braver<br />

suicides, their loss barely reported,<br />

some never missed, the majority kept<br />

long enough for the waves to maul them faceless;<br />

the solar beast that vainly flared, the roaring<br />

water-noise as they fought and dropped past caring?<br />

I’m history. So are you. Flow on, flow nowhere.<br />

(Ambhas : Sanskrit for ‘water’; believed to be the origin <strong>of</strong> the name ‘Humber.’)<br />

28

Spurn Head<br />

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

Ambhas is fat and slow and sorrowful<br />

Today. She feels she’s always on the wrong side<br />

Of the dunes – and this is an accurate perception.<br />

Changes <strong>of</strong> heart are runnels in the sand,<br />

That never go far enough: her aspirations<br />

A mile <strong>of</strong> marsh grass, patchy and withered.<br />

She looks up, lachrymose, and imagines being where<br />

The atmosphere is dry and radiant, sparkling<br />

With buckthorn-fruit, plastered like orange coral<br />

Around ungrateful wrists, and gorse-flowers, plump-lipped<br />

In an occupational kiss. She doesn’t envy<br />

Their wind-crazed glamour, but their vantage-point.<br />

They see so far. They can always see her darling<br />

Gracefully showing <strong>of</strong>f his specialised muscles,<br />

Pimping his creamy plumage for anyone, no-one.<br />

She pretends she has never touched him, never licked<br />

A salt-grain <strong>from</strong> his tongue. Nothing will change,<br />

When his glittering cross-purposes subsume her<br />

In the next longed-for moment, nothing will brim her<br />

But her own muddled energy and shadows.<br />

They dawn on her like nausea, and she’s<br />

Already breaking up, like a caller’s voice in a tunnel;<br />

Already heaving her yellow flesh against the barrier wall.<br />

29

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

Malcolm Watson Philip and the Monsters<br />

He’s come again to the meridian, that’s neither east<br />

nor west. To here. To nowhere. Forward to the past,<br />

fast-receding like the ebb-tide, through carucates<br />

and wapentakes, oxgangs and hides,<br />

here to the lovely Queen <strong>of</strong> Holderness.<br />

Happy as a child let out to splash through puddles<br />

and annihilate the mirrored sky. Captain Bligh,<br />

he knows, that Captain Bligh, surveyed the sly<br />

and ever-shifting shoreline <strong>from</strong> this spire.<br />

How <strong>of</strong>ten has he traced this graceful arrow’s flight<br />

into the sky? How many times? How <strong>of</strong>ten have<br />

these gargoyles glared at him beneath the crockets<br />

and the crenellations? Familiar demons. A fiend gripping<br />

a sinner. A man holding a pig. A bagpiper and fiddler.<br />

A lion thrusting out his tongue. A soldier slitting<br />

a woman’s throat. A grinning monster grasping a girl.<br />

Samson rending the lion’s jaw. He smiles. Rain dripping<br />

<strong>from</strong> their gullets spatters the sodden shoulders <strong>of</strong> his mac.<br />

Inside, the frowsty smell he loves. Silence. Sudden sunlight<br />

slides through transoms and tracery, splashing the walls,<br />

illuminating aisles and arches, ogee hoodmoulds, vaulting,<br />

blind-arcading, spandrels, paterae, the chancel screen.<br />

Everything in sharp relief. The soldiers on the Easter<br />

Sepulchre. The ornamented capitals, no two alike.<br />

He marvels and looks up, and up. And suddenly he spies<br />

a hundred faces staring down he’d never seen before.<br />

Imps. Boggarts. Shapeless things. Blemyae. Deformed<br />

30

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

and leering, gaping mouths and eyes like knives. Oh God, like<br />

knives. They slink slowly into darkness as the clouds blanket<br />

the sky. He stumbles to the reredos and sees the loving<br />

look the Virgin gives her child. His heart catches, knowing<br />

that he does not sleep on light and wake to kisses. The earth<br />

swallows the sun, turns hot beneath his feet among the shadows<br />

<strong>of</strong> the nave. Back on the lonely road to <strong>Hull</strong> <strong>from</strong> Patrington,<br />

an empty hearse shoots past at speed. He smiles again,<br />

and sits up higher in the saddle in the November rain.<br />

Malcolm Watson: Lonelier and lonelier... and then the sea<br />

31

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

Keyingham, Midwinter 1898<br />

The boneyard’s crammed. The ground<br />

is gorged. It isn’t meet to stack the dead<br />

like cordwood for the winter. These last<br />

three years, since 1895, we have convened<br />

a score <strong>of</strong> times and studied maps and deeds<br />

and rolls and boundaries. All our requests<br />

have come to naught. The last negotiation<br />

failed at Cherry Garth; the brewer, fearful<br />

that his water would be soured, turned us<br />

down. Now the Parish has secured a site<br />

on Eastfield Road, a fit and seemly site<br />

that will not be water-logged and ought<br />

to serve a century. We had no clue,<br />

when we appointed Mr Goundrill as<br />

gravedigger in November, that before<br />

Twelfth Night, his daughter Florrie,<br />

seven months, would be the first<br />

that he must put in that cold ground.<br />

32

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

Kath McKay<br />

Craters, lava plains, mountains and valleys<br />

‘Salt and vinegar?’<br />

Vicky, my wife, shovels cod and chips into greasepro<strong>of</strong> bags.<br />

The acrid smell <strong>of</strong> malt vinegar catches at our throats.<br />

Three weeks since we started working together and today a<br />

customer tells me that a new chip shop has opened round the<br />

corner.<br />

The queue shuffles forward. I bang drink cans hard on the<br />

counter and fill the fridge.<br />

This new brown-haired Vi, with her roots showing, feels like a<br />

stranger, all false smiles and easy phrases.<br />

‘Lovely day.’<br />

‘Nice out.’<br />

I gather up cardboard packaging and squash it into a plastic<br />

bin. Then I lift a large pan <strong>of</strong> peeled potatoes towards the chip<br />

cutter. Vicky frowns. She says I’m unfit; that we should move to<br />

frozen.<br />

It’s always a miracle how the stubby chips fall out, like larvae<br />

hatching. When the bucket is full, I load up the fryers and scrape<br />

out the serving hatches. I pause, serving spoon in hand. The view<br />

is <strong>of</strong> boarded up shops, and people hurrying. Everyone’s broke.<br />

Rain oozes down. If this keeps up, people will stay home and<br />

eat frozen pizza, drains will fill and burst again, the streets will<br />

smell <strong>of</strong> sewage.<br />

I wriggle out <strong>of</strong> my white coat, throw on a jacket.<br />

‘Back soon.’<br />

‘Where are you going? What if we get a big queue?’<br />

I shrug, hand on the door.<br />

Then I’m down at the old pier, staring out at rough waves,<br />

cold rain on my face. The heave and tug <strong>of</strong> the water, the pull <strong>of</strong><br />

33

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

the far <strong>of</strong>f sea. My father helped fill in this dock, driving lorry<br />

roads <strong>of</strong> rubble back and forth, arriving home sweaty and dusty,<br />

the first work he’d had for years.<br />

‘Filling in, concreting over, that’s what this place is about<br />

now,’ he said.<br />

The cobbles are wet with rain.<br />

Back in the shop Vicky has her head in a book.<br />

‘The Golden Fleece,’ she says.<br />

Savagely, I extract a piece <strong>of</strong> cod, and stomp to the back room<br />

where I eat with my fingers.<br />

Vicky hates it when I don’t use a knife and fork:<br />

‘Eat proper.’<br />

The afternoon wears on: we load the dishwasher, arrange sheets <strong>of</strong><br />

greasepro<strong>of</strong> paper, stack food cartons, refill the forks container.<br />

‘Are you going tonight?’ she asks.<br />

Me, a grown man. Embarrassing.<br />

When she raises her arms, there’s a loose layer <strong>of</strong> fat hanging<br />

<strong>from</strong> her upper arm. A wave <strong>of</strong> love steals over me. She is on my<br />

side.<br />

‘Are you?’<br />

‘OK.’<br />

‘Good.’<br />

And she kisses me full on the lips. I taste salt.<br />

‘Don’t worry. It’ll be fine.’<br />

‘Control to Houston. Hello?’ A customer in a wet mac wipes<br />

rain <strong>of</strong>f his glasses, and Vicky, blushing, serves him. I hear my<br />

grandfather’s voice: Pollack, Flounder, Shark. Fish is what made this<br />

place. We’ll always survive with fish.<br />

‘Pollack, Flounder, Shark,’ I say aloud. The customer scuttles<br />

away.<br />

We turn the sign to ‘Closed.’<br />

34

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

The session is held in a draughty portacabin, with tea <strong>from</strong> a<br />

machine.<br />

Vicky’s still up when I get back, the living room table covered in<br />

paper, cuttings, an old notebook.<br />

‘What you doing?’<br />

She pores over squiggles, and reads.<br />

‘250,000 miles <strong>from</strong> the moon to the earth. There is no wind<br />

or weather on the moon. No water. The moon influences fishing.<br />

Fishermen <strong>of</strong>ten consult the moon before they decide when to<br />

fish. The footprints left by the Apollo crew will remain for millions<br />

<strong>of</strong> years. The moon is 4.4 billion years old. Its surface consists <strong>of</strong><br />

craters, lava plains, mountains and valleys.’<br />

‘What?’<br />

‘Crater, lava plains, mountains and valleys.’<br />

‘Craters, lava plains, mountains and valleys,’ I repeat. ‘I didn’t<br />

know you were interested in the moon.’<br />

There are parts <strong>of</strong> her I know nothing about.<br />

‘My dad was obsessed. I was conceived the night <strong>of</strong> the moon<br />

landing. It’s in my blood.’<br />

‘Yeah?’<br />

I want to laugh, but her face is dreamy.<br />

‘Every year, on July 20, we’d watch the video. My mum even<br />

made fairy cakes with silver baubles on, called them moon cakes.<br />

‘Huh?’<br />

Her family did something together.<br />

‘It was fun. But one year, I fell asleep, and when I woke,<br />

Armstrong was still padding across the Sea <strong>of</strong> Tranquillity, and the<br />

real moon was coming in through the window. Everything was<br />

silvery, like the moon was in the room.’<br />

I put out my hand. Hers is warm and s<strong>of</strong>t and I want to bury<br />

myself in it.<br />

‘And then what?’<br />

35

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

‘I decided to become an astronaut.’<br />

Her face stops me laughing.<br />

‘The careers <strong>of</strong>ficer said there wasn’t much call for astronauts<br />

in <strong>Hull</strong>.<br />

“You’re good with your hands,” he said. “There’s a free<br />

hairdressing taster course at the college. Interested?” And no, he<br />

didn’t want to see my moon scrapbook.’<br />

I kiss her head.<br />

‘Anyway, how was your night?’<br />

‘They gave us Garibaldi biscuits, and made us read a poem.’<br />

‘Show us.’<br />

‘That Whitsun, I was late getting away,’ she reads. I repeat the<br />

lines after her as we press our thighs together.<br />

The next day she’s on King Midas.<br />

‘Everything he touched turned to gold.’<br />

Scary.<br />

Through September, I go the classes twice a week. My dad used to<br />

point out notices: Danger. Do not touch. And recite lists <strong>of</strong> ports he<br />

travelled to: Stavanger, Rotterdam, Helsingfors. He’d buy me comics<br />

and borrow books <strong>from</strong> the library. But nothing stuck. Now it’s<br />

like putting on glasses: everything clearer.<br />

Takings are down: each day fewer customers. Then the other shop<br />

shuts after the police take the owner away. There are rumours<br />

about dealing.<br />

Vi says we’ve got a chance. So we paint one wall <strong>of</strong> the shop<br />

black, and scrawl ‘traditional’ in big letters.<br />

A man in the queue says ‘every good fish needs a poem.’ Pulls<br />

a piece <strong>of</strong> paper <strong>from</strong> his pocket, and pins it on the wall.<br />

Soon the wall is full <strong>of</strong> poems. Word spreads, and we’re busy<br />

again.<br />

36

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

One autumn night a meteor shower streaks across the sky. It looks<br />

like the interference on old TVs, but Vicky’s zinging. Says just<br />

because she can’t be an astronaut doesn’t mean she can’t be<br />

interested in space. Goes online, joins a group.<br />

In the morning, we wake early, and bring tea back to bed.<br />

She’s fizzing.<br />

‘Read to me,’ she says. ‘That poem you started with.’<br />

When I get to the bit with the ‘arrow-shower’, we fall into<br />

each other.<br />

Behind us, there is rain.<br />

Malcolm Watson: Sunk Island Sands<br />

37

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

Sarah Stutt Notice to Mariners<br />

Keep your eye on the swans at New Holland.<br />

Wait for them to leave the dock at slack water,<br />

for everyone knows the difficulty <strong>of</strong> mooring,<br />

knowing when and where to drop anchor.<br />

Use the backscatter <strong>of</strong> your own lights<br />

to find your way home, at Skitter Haven,<br />

South Shoal, Holme Ridge and Killingholme,<br />

on to Paull Sand and Pyewipe Outfall.<br />

If you tune to the frequency <strong>of</strong> love, at the bridge,<br />

you might see a mother and son, playing on the walkway,<br />

hear the delicate sound <strong>of</strong> descent and disappearance<br />

before they are wrapped in the skin <strong>of</strong> river, bone by bone.<br />

A pilot steamer is holed, portside in the engine room.<br />

Fog swallows the four long blasts <strong>from</strong> her steam whistle<br />

before she vanishes, followed by a commotion<br />

<strong>of</strong> wild geese, signalling the desire to be gone.<br />

They are burning reed over at Faxfleet<br />

when a woman appears <strong>from</strong> the smoke,<br />

holding out her thin hands, all moon-grey silk<br />

and bruise-blue eyes. Some say it is the river, rising.<br />

Heaven leaks onto the water at Stony Binks<br />

as ships clear the Sunk Dredged Channel<br />

at the Sunk Spit Buoy, coursing ahead<br />

in the imaginary gap between river and sky.<br />

38

Where do the arguments <strong>of</strong> the sea end<br />

and the sweet nothings <strong>of</strong> the river begin?<br />

Somewhere between Spurn and Donna Nook,<br />

past the catacomb <strong>of</strong> gull bones at Bull Sand Fort.<br />

Determined not to fall away into the dark,<br />

a defiant finger <strong>of</strong> land fights against erasure.<br />

Muntjac deer bark at the stars as rail lines<br />

steer into the fabric <strong>of</strong> the invisible.<br />

Cliff Forshaw: Spurn Lightship<br />

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

39

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

Scat Singing in Pearson Park<br />

It was a day much like this,<br />

a day with a rose behind its ear.<br />

You were here, hopelessly drunk<br />

on summertime and jazz.<br />

The same, pale-skinned hoods<br />

and carrier bag couture but you,<br />

you had them tuxedoed, in bowler hats,<br />

swinging to an easy riff and scat-singing.<br />

Loose-lipped and just out <strong>of</strong> time<br />

you always played an extra bar,<br />

leant on notes until they split<br />

adding the after-kiss <strong>of</strong> a cymbal.<br />

Skinny men with holes for eyes,<br />

old folk mesmerised<br />

by a staccato bass, drum breaks,<br />

a breath <strong>from</strong> an earlier world.<br />

Children agog, all ears cocked<br />

to supple, rocketing phrases,<br />

nimble, silky reeds,<br />

the simple trick <strong>of</strong> a suspended<br />

beat.<br />

Now slump-shouldered boughs<br />

are overwhelmed by moss.<br />

Heavy, brute-faced dogs<br />

forage in cans at Albert’s feet.<br />

Strident geese heckle the ducks<br />

40

above the feeble rush <strong>of</strong> the fountain.<br />

I follow two tramps<br />

in tragic, baggy pants,<br />

their trolleys filled with nowhere<br />

into Beverley Road,<br />

the street you called<br />

‘a charming chaos<br />

<strong>of</strong> harmonic innovations’ –<br />

shrill, rapid yelps,<br />

rips, slurs, distortions,<br />

a black van charging<br />

with ‘urgent blood’.<br />

Antone’s Guitars,<br />

The Gig Shop,<br />

Slave to the Beat<br />

and the bunting is up<br />

for part-exchange cars.<br />

There is Vodka Blue Charge<br />

at the Cannon Junction,<br />

a shoreline <strong>of</strong> fag-ends<br />

by The Haworth Arms.<br />

I wait for the bus to a cabaret <strong>of</strong> sirens,<br />

the hoarse vocals <strong>of</strong> an orange council van,<br />

remembering those downward runs,<br />

missed cues and you, scooping the air<br />

with your trombone.<br />

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

41

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

Christopher Reid The Clarinet<br />

Lecherous licorice-stick,<br />

with equal ease<br />

you do sweet, you do salty,<br />

you do slow, you do quick.<br />

As soon as lips, tongue<br />

and nimble fingers have primed you,<br />

you’re <strong>of</strong>f to play<br />

among your several registers:<br />

<strong>from</strong> low and guttural,<br />

mucky-edged, molasses-black,<br />

no-apologies down and dirty,<br />

through middle regions<br />

<strong>of</strong> melisma and vibrato,<br />

where extravagant soul-vistas<br />

may tempt you to linger –<br />

but you can’t, because nobody’s<br />

allowed to live for ever –<br />

to those heights where things are apt<br />

to move at a lick,<br />

scampering headlong, squealy-slick,<br />

towards a conclusion<br />

both triumphant and sad.<br />

Then, indefatigable<br />

Jim Dandy, Jack the Lad,<br />

as if you’d learned nothing,<br />

you start up again.<br />

42

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

Malcolm Watson Blues at the Black Boy<br />

Nobody Knows The Way I Feel. I Want You Tonight,<br />

Ma Petite Fleur. If I Could Be With You One Hour Tonight,<br />

Spreadin’ Joy. Old-Fashioned Love. Careless Love!<br />

What A Dream,<br />

Sweetie Dear. Squeeze Me. Slippin’ And Slidin’. Wha’d Ya Do To<br />

Me?<br />

Happy Go Lucky Blues. Breathless Blues. Pounding Heart Blues.<br />

Oh, Lady, Be Good. You’re The Limit. It’s No Sin.<br />

Temptation Rag. I’ve Found A New Baby. Out Of Nowhere.<br />

Deux Femmes Pour Un Homme. Ain’t Misbehavin’. I Know<br />

That You Know. As-Tu Le Cafard? La Complainte Des Infidèles.<br />

Just One Of Those Things. Nuages. Blood On The Moon.<br />

Okey Doke. Blame It On The Blues. Saturday Night Blues.<br />

Lonesome Blues, Jackass Blues. Blues, My Naughty Sweetie.<br />

What Is This Thing Called Love? What I Did To Be Black And<br />

Blue.*<br />

Blues In My Heart. Weary Blues, Old Man Blues. Sobbin’ And<br />

Cryin’.<br />

Blues In The Air. Gone Away Blues. I Had It, But It’s All Gone<br />

Now.<br />

Loveless Love. Save It, Pretty Mama. You’ve Got Me Walkin’<br />

And Talkin’<br />

To Myself. Ce Mossieu Qui Parle. Oh, Didn’t He Ramble. That’s<br />

What Love<br />

Did To Me. That’s The Blues, Old Man. There’ll Be Some<br />

Changes Made…<br />

* All titles <strong>of</strong> Sidney Bechet tracks, except this one by Muggsy Spanier.<br />

43

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

Saint Helen’s Well, Great Hatfield, Holderness<br />

The church, sacred to the dam <strong>of</strong> Constantine, has disappeared,<br />

leaving a graveyard. Stones and bones. The holy well remains<br />

close by, ancient before the emperor and forever young.<br />

Saint Helen in her dotage made the holy pilgrimage<br />

to the Holy Land and found Golgotha and the Cross,<br />

the Crown <strong>of</strong> Thorns and three nails <strong>from</strong> His feet<br />

and hands. One she kept, and two she gave her son<br />

who wore them on his helm and golden bridle chain.<br />

The church has gone. The holy well remains, forever young,<br />

remembering the ancient prayers to pagan gods and nymphs<br />

and water sprites. A hawthorn hedge surrounds it still,<br />

surrounds the steps and ledge that face the eastern sun.<br />

And people come in May before sunrise to dip a rag<br />

into the spring and hang it on the sacred thorns to pray<br />

for blessings, favours, health… Uath, Celtic tree <strong>of</strong> Beauty<br />

whose blossoms crown the Queen <strong>of</strong> May, whose flowers<br />

draw out thorns and splinters, whose berries (still called<br />

cuckoo’s beads and pixie pears) will slow a racing heart.<br />

The lacy blossom ushers luck into the house. The holy plant<br />

that made the Crown <strong>of</strong> Thorns will heal a broken heart,<br />

shoo anger, blame and guilt away. The church has gone.<br />

And every May before sunrise, the holy spring is dressed by unseen<br />

hands with garlands, sprays <strong>of</strong> flowers; the dewy thorns adorned<br />

with dripping tokens, fluttering rags and ribbons drying in the sun.<br />

44

Four-Minute Warning: Kilnsea<br />

A monstrous Heath-Robinson contraption. A ton<br />

<strong>of</strong> concrete moulded to a concave trumpet on<br />

a concrete plinth at Kilnsea. Acoustic mirror<br />

at whose focal point there sits a pipe snaking<br />

away behind the Brobdingnagian ear towards<br />

a troglodytic gnome who strains to hear<br />

the thrum <strong>of</strong> Zeppelin engines far away.<br />

If he’s sure, but only if he’s sure, he has<br />

4 minutes to alert the O/C at the Godwin<br />

battery to blast away the vast dirigible<br />

and save <strong>from</strong> being flattened the burgesses<br />

<strong>of</strong> Scarborough. Listening, listening, listening…<br />

The fellow in the headset suffers <strong>from</strong> anxiety,<br />

the fidgets and dyspepsia. He’s replaced.<br />

<strong>Under</strong> <strong>Travelling</strong> <strong>Skies</strong><br />

He ends up in the hospital at Kilnsea housing thousands<br />

<strong>of</strong> the maimed and wounded, lifted <strong>from</strong> the trains<br />

<strong>from</strong> <strong>Hull</strong>. The men transfer to cemeteries or to training<br />

centres, studying prosthetic manipulation, adaptability,<br />

survivability. Lieutenant J.R.R. Tolkein, just recently<br />

recovered <strong>from</strong> trench fever on the Somme, guards<br />

the Holderness peninsula <strong>from</strong> Orcs. The hospital<br />

is replaced by a TA base, which is replaced<br />