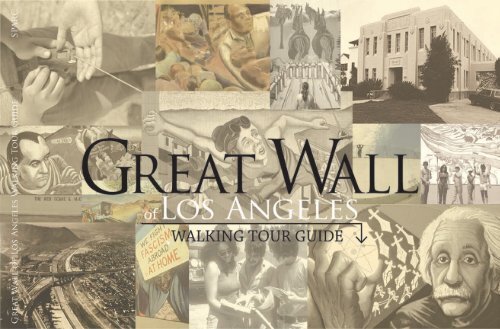

great wall walking tour book - School of Architecture and Allied Arts ...

great wall walking tour book - School of Architecture and Allied Arts ...

great wall walking tour book - School of Architecture and Allied Arts ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

THE RIVER...1<br />

THE TATOO ON THE SCAR WHERE THE RIVER<br />

ONCE RAN...3<br />

GREAT WALL HISTORY...5<br />

ABOUT SPARC...7<br />

GREAT WALL INTRODUCTION...8<br />

ABOUT THE ARTIST - JUDITH F. BACA...9<br />

HOW IT HAPPENED...11<br />

HOW ITS DONE..12<br />

THE 1976 PROJECT: THE FIRST ONE 1000 FT...15<br />

PRE HISTORIC CALIFORNIA...18<br />

SPANISH ARRIVAL...20<br />

1848 BANDAIDE...22<br />

SOJOURNERS...24<br />

1890 L.A. MOUNTAINS TO THE SHORE...26<br />

THE 1978 PROJECT: THE 1920s...27<br />

WORLD WAR I...30<br />

A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON EDISON...32<br />

1980 PROJECT: THE 1930s...33<br />

ILLUSION <strong>of</strong> PROSPERITY...36<br />

CRASH AND DEPRESSION...38<br />

DUSTBOWL REFUGEES...40<br />

1981PROJECT: THE 1940s...41<br />

WORLD WAR II...44<br />

DR. CHARLES DREW...46<br />

ZOOT SUIT RIOTS...48<br />

JEWISH REFUGEES...50<br />

1983 PPROJECT: THE 1950s...51<br />

FAREWELLTO ROSIE THE RIVETER...54<br />

DEVELOPMENT OF SUBURBIA...56<br />

THE RED SCARE...58<br />

CHAVEZ RAVINE AND THE DIVISION OF...60<br />

THE BIRTH OF ROCK AND ROLL...62<br />

ORIGINS OF THE GAY RIGHTS MOVEMENT...64<br />

THE BEATS...66<br />

JEWISH ACHIEVEMENTS IN ARTS AND<br />

SCIENCE...68<br />

INDIAN ASSIMILATION...70<br />

ASIANS GAIN CITIZENSHIP AND PROPERTY...72<br />

OLYMPIC CHAMPIONS 1948-1964...74<br />

GREAT WALL TESTIMONIALS...75<br />

MURAL MAKER TESTIMONIALS...76<br />

THE ERNESTINE JIMENEZ STORY...80<br />

GREAT WALL FUTURE...82<br />

INTERPRETIVE STATIONS...84<br />

NEW DESIGNS FOR THE1960s - THE 1990s...86<br />

MAP...87<br />

FURTHER INFORMATION ON THE GREAT<br />

WALL...88<br />

DIRECTIONS...89<br />

CONTACT SPARC...90<br />

CREDITS...90<br />

GREAT WALL PANORAMIC... 91

THE RIVER<br />

The history <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles begins with a river. It is on the bank <strong>of</strong> this river that the first settlement, which consisted<br />

<strong>of</strong> 22 people <strong>of</strong> black <strong>and</strong> meztiso was formulated. They were outcast from their homel<strong>and</strong>s in Mexico<br />

<strong>and</strong> came north in mule-trains to arrive at the banks <strong>of</strong> the river. Upon arrival, these people found that there was<br />

adequate water, vegetation <strong>and</strong> wildlife to support human <strong>and</strong> they formulated the first settlement.<br />

It wa at the base <strong>of</strong> this river, the city <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles was founded. Settlers found that the river was troublesome.<br />

It began to overflow its banks, <strong>and</strong> as they created these settlements they found that the river did not behave<br />

properly -- it had a tendency to swell in the winter months, contract in the summer months. As it swelled it took<br />

over parts <strong>of</strong> the settlement.<br />

It was very early in the 1920s that the army core visionaries began to systematically concrete the river. Believing<br />

it had to be tamed, they hardened the arteries <strong>of</strong> the l<strong>and</strong>. By the 1970’s they completed the concreting <strong>of</strong> this<br />

river. In the photos to the right you’ll se what this river looked like: It became regularized. In a sense the water<br />

no longer flowed into the aqueduct because the bottom <strong>of</strong> these channels were concreted. So water actually<br />

flowed much more swiftly to the ocean. It had many affects. One <strong>of</strong> the major affects was the loss <strong>of</strong> the water<br />

from the aqua fur. The other was that it caused tremendous pollution in the bay.<br />

A relationship exists between the disappearance <strong>of</strong> the river <strong>and</strong> the people: If you can disappear a river how<br />

much easier is it to disappear the history <strong>of</strong> the people?<br />

1

2<br />

bridge construction picture

THE TATOO ON THE SCAR WHERE THE RIVER ONCE RAN<br />

“What I saw [looking at the river one day] was this metaphor: the hundreds <strong>of</strong> miles <strong>of</strong> concrete conduits<br />

were scars in the l<strong>and</strong>. They recalled the scars I had seen on a young man’s body in a Los Angeles Barrio.<br />

Fern<strong>and</strong>o, my friend <strong>and</strong> mentee, had suffered multiple stab wounds in East Los Angeles’ gang warfare. I<br />

asked him how he was feeling after the attack. “My wounds are healing,” he said. “But every time I lift my<br />

shirt, I see my body as a map <strong>of</strong> violence. So together we began to design transformative tattoos in an effort<br />

to make the ugly marks into something powerful <strong>and</strong> beautiful.<br />

That day, overlooking the channel, I saw a relationship between the scars on his body <strong>and</strong> the scars in this<br />

l<strong>and</strong>. I dreamed <strong>of</strong> a tattoo on the scar where the river once ran as a metaphor for healing our city’s divisions<br />

<strong>of</strong> race <strong>and</strong> class <strong>and</strong> proposed the Great Wall <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles. I dared not speak aloud the words that<br />

I am saying today, that the concreting <strong>of</strong> the river was an act <strong>of</strong> violence against the earth <strong>and</strong> healing was<br />

needed for both the river <strong>and</strong> the people.<br />

In a sense the <strong>great</strong> <strong>wall</strong> is the tattoo on the scar where the river once ran. It is a similar story in the sense that<br />

as the arteries were hardened <strong>and</strong> the river disappeared, so were the people disappeared, so were stories <strong>of</strong><br />

the people that were the originating peoples <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles. The disappearance <strong>of</strong> the river <strong>and</strong> the disappearance<br />

<strong>of</strong> the people seemed to have a common ground. We set about producing this long half a mile <strong>of</strong><br />

mural to tell the story <strong>of</strong> the people that had been disappeared from history <strong>book</strong>s.<br />

For 12 years, 400 young people worked on the recovery <strong>of</strong> their histories, practicing a connection to each other<br />

across racial, class <strong>and</strong> gender differences. We worked to tattoo the scar where the river once ran there, in<br />

the San Fern<strong>and</strong>o Valley, with images that would remember our dismembered history. Life long connections<br />

were made there between us all.”<br />

- Judith F. Baca<br />

3

Fern<strong>and</strong>o picture<br />

4

GREAT WALL HISTORY<br />

The Great Wall <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles, a l<strong>and</strong>mark pictorial representation <strong>of</strong> the history <strong>of</strong> ethnic peoples <strong>of</strong> California<br />

from prehistoric times to the 1950’s, is one <strong>of</strong> the country’s most respected <strong>and</strong> largest monuments to inter-racial<br />

harmony. Conceived by SPARC’S artistic director <strong>and</strong> founder Judith F. Baca, it is SPARC’s first public art project<br />

<strong>and</strong> its signature piece. The Great Wall was begun in 1974 <strong>and</strong> completed over five summers, employing over<br />

400 youth <strong>and</strong> their families from diverse social <strong>and</strong> economic backgrounds working with artists, oral historians,<br />

ethnologists, scholars, <strong>and</strong> hundreds <strong>of</strong> community members.<br />

Its half-mile length (2,754 ft) in the Tujunga Flood Control Channel <strong>of</strong> the San Fern<strong>and</strong>o Valley with accompanying<br />

park <strong>and</strong> bike trail hosts thous<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> visitors every year, providing a vibrant <strong>and</strong> lasting tribute to the working<br />

people <strong>of</strong> California who have truly shaped its history. In 2000 <strong>and</strong> 2001 SPARC received acknowledgement <strong>and</strong><br />

support from the Ford Foundation’s Animating Democracy: The Role <strong>of</strong> Civic Dialogue in the <strong>Arts</strong> initiative <strong>and</strong><br />

from the Rockefeller Foundation Partnership’s Affirming Community Transformation initiative to continue work on<br />

the Great Wall, to hold civic dialogue sessions, <strong>and</strong> to ultimately design the four decades <strong>of</strong> the 20th century that<br />

remain absent from the mural (the 1960, 1970, 1980 <strong>and</strong> 1990s). In 2006, SPARC was awarded with a California<br />

Cultural <strong>and</strong> Historical Endowment grant as well as a grant from the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy to<br />

acquire <strong>and</strong> develop a new solar-lit bridge with interpretive stations, to construct five additional interpretive<br />

stations along the <strong>wall</strong>, to design the next four decades (60’s, 70’s, 80’s, & 90’s), <strong>and</strong> to develop conservation<br />

education programs. The mural’s restoration (a critical need) <strong>and</strong> continuation, with future panels produced by<br />

the next generation <strong>of</strong> children <strong>of</strong> the Great Wall, remains a vital, ongoing program <strong>of</strong> SPARC. Our latest goal is<br />

the creation <strong>of</strong> a full use park <strong>and</strong> green bridge at the Great Wall thereby establishing the site as an international<br />

educational <strong>and</strong> cultural destination point.<br />

5

ABOUT SPARC<br />

SPARC, the Social <strong>and</strong> Pulibc Art Resource Center, is a cultural center that believes public art to be a vehicle<br />

for fostering civic dialogue, promoting cross-cultural underst<strong>and</strong>ing, <strong>and</strong> addressing critical social issues. We<br />

accomplish our mission by producing, preserving <strong>and</strong> teaching community-based, public art.<br />

SPARC’s intent is to examine what the public chooses to memorialize through public art, <strong>and</strong> to devise<br />

<strong>and</strong> produce artworks through innovative participatory processes that include creative visualization <strong>and</strong><br />

collaboration with local residents. We have been working with Los Angeles’ poor <strong>and</strong> immigrant communities,<br />

youth, children, <strong>and</strong> families for over thirty years. These community members are participants in the production<br />

<strong>of</strong> public monuments. Through our processes, their stories are made accessible to local, national <strong>and</strong><br />

international audiences.<br />

7

GREAT WALL INTRODUCTION<br />

The Great Wall <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles, with its adjoining viewing trails <strong>and</strong> park, are a public monument to the stories<br />

<strong>of</strong> California’s ethnic groups underrepresented in history texts <strong>and</strong> public consciousness. It is the only visual<br />

narration <strong>of</strong> its kind in a public space. A half-mile long work <strong>of</strong> art created during the Civil Rights activism <strong>of</strong> the<br />

70’-80’s, this mural’s inception marks a significant event in 20th century Californian History.<br />

“The Great Wall” is also a seminal work <strong>of</strong> public art created during California’s Chicano Mural Art Renaissance,<br />

whose practitioners went well beyond highlighting a singular ethnic identity to expound a view <strong>of</strong> the rich<br />

ethnic diversity <strong>of</strong> our state. Decade by decade, the <strong>wall</strong> marked culturally significant changes in California’s<br />

demographics in both the stories represented in the mural <strong>and</strong> by the participants who created it.<br />

8<br />

Image by TOC<br />

Ariel Photo <strong>of</strong> the Los Angeles River Basin

ABOUT THE ARTIST - JUDITH F. BACA<br />

“In 1975, when the Great Wall was still a dream, I never imagined it would lead over 400 young “Mural Makers”<br />

<strong>and</strong> 36 artists (including myself) through such a moving set <strong>of</strong> experiences. Nor could I have imagined that over<br />

30 years from the date the first paint was applied to the <strong>wall</strong> that it would still be a work in progress.<br />

‘When I first saw the <strong>wall</strong>, I envisioned a long narrative <strong>of</strong> another history <strong>of</strong> California; one which included<br />

the ethnic peoples, women, <strong>and</strong> minorities who were all so invisible in conventional text<strong>book</strong> accounts. The<br />

discovery <strong>of</strong> the history <strong>of</strong> California’s multi-cultured population was a revelation to me as well as to the<br />

members <strong>of</strong> my teams. We learned each new decade <strong>of</strong> history in summer installments; the 20’s in 1978, the<br />

30’s in 1980, the 40’s in 1981, <strong>and</strong> the 50’s in 1983. Each year our visions exp<strong>and</strong>ed as the images traveled<br />

down the <strong>wall</strong>. While our sense <strong>of</strong> our individual families’ places in history took form, we became family to one<br />

another. Working toward the achievement <strong>of</strong> a difficult common goal shifted our underst<strong>and</strong>ings <strong>of</strong> each other<br />

<strong>and</strong> most importantly <strong>of</strong> ourselves.<br />

‘I designed this project as an artist concerned, not only with the physical aesthetic considerations <strong>of</strong> a space,<br />

but also the social, environmental <strong>and</strong> cultural issues affecting the site as well. I am not a social worker, though<br />

people mistakenly call me one <strong>and</strong> I am not a teacher although I have teaching skills. I draw on skills not<br />

normally used by artists. I’ve learned as much as I’ve taught from the youth I’ve had the good fortune to know<br />

by working alongside <strong>of</strong> them. They’ve taught me, among other things, how to laugh at myself, how to put play<br />

into hard work, <strong>and</strong> how not to be afraid to believe in something. I am extremely grateful.<br />

‘Perhaps most overwhelming to me about the Great Wall experience has been learning <strong>of</strong> the courage <strong>of</strong><br />

individuals in history who endured, spoke out, <strong>and</strong> overcame seemingly insurmountable obstacles. It was true<br />

both <strong>of</strong> the people we painted about <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> ourselves, the Mural Makers.”<br />

- Judith F. Baca<br />

9

10<br />

(caption needed)

HOW IT HAPPENED<br />

In 1974, the Army Corps <strong>of</strong> Engineers contacted Judith F. Baca about the possibility <strong>of</strong> creating a mural in the<br />

flood control channel as part <strong>of</strong> a beautification project that included a mini park <strong>and</strong> a bicycle path. Two years<br />

later the conversion <strong>of</strong> concrete eyesore into community treasure began.<br />

Production <strong>of</strong> the Great Wall has involved the support <strong>of</strong> many government agencies, community organizations,<br />

businesses, corporations, foundations, <strong>and</strong> individuals. In the first several years, SPARC received a <strong>great</strong> deal<br />

<strong>of</strong> support for the project from governmental juvenile justice funding sources, such as the Summer Youth<br />

Employment Program, the Army Corps <strong>of</strong> Engineers, <strong>and</strong> the Flood Control District. In recent years, more private<br />

sector funding has made the Great Wall possible.<br />

By 1976, the Great Wall was already the longest mural in the world: one thous<strong>and</strong> feet <strong>of</strong> California history from<br />

the days <strong>of</strong> the dinosaurs to 1910 had already been painted in the Tujunga Wash drainage canal <strong>of</strong> the San<br />

Fern<strong>and</strong>o Valley. But Baca – artistic director <strong>of</strong> the Social <strong>and</strong> Public Art Resource Center in Venice, California<br />

– was not ready to stop at 1910. Mural Makers continued to work in the wash throughout the summers <strong>of</strong> 1978,<br />

1980, 1981 <strong>and</strong> 1983. Each year they added 350 feet <strong>and</strong> a decade <strong>of</strong> history seen from the viewpoint <strong>of</strong><br />

California ethnic groups, about heir contributions <strong>and</strong> their struggles to overcome obstacles.<br />

By 1980 the mural, dubbed “The Great Wall” rather than its <strong>of</strong>ficial name “The History <strong>of</strong> California,” stretched<br />

more than a third <strong>of</strong> a mile <strong>and</strong> had consumed approximately 600 gallons <strong>of</strong> paint <strong>and</strong> 65,000 hours. With the<br />

completion <strong>of</strong> the decade <strong>of</strong> the Forties in September <strong>of</strong> 1981, the total length reached 2,085 feet while the<br />

number <strong>of</strong> young people who had worked on the mural rose to 185. In the summer <strong>of</strong> 1983, a new segment was<br />

painted, depicting the decade <strong>of</strong> the 1950’s. To date, the length <strong>of</strong> the Great Wall totals 2,754 feet, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

number <strong>of</strong> participating youths totals over 400.<br />

However impressive the currently completed segments may be, they are only part <strong>of</strong> a work in progress. The<br />

completed mural, which will run for nearly a mile, will take history to the present in future panels which will<br />

be formulated by a planning commission composed <strong>of</strong> new <strong>and</strong> veteran youth Mural Makers, artists, <strong>and</strong><br />

representatives for the Great Wall’s diverse sponsors.<br />

11

The mural was flooded five times between 1976 <strong>and</strong> 1983, with water rising as high as Edison’s nose.<br />

However, more dangerous than water damage is the effect <strong>of</strong> air pollution, years <strong>of</strong> exposure to direct<br />

sunlight, <strong>and</strong> fertilizer damage from the adjoining park lawns.<br />

Painted during the first summer <strong>of</strong> work in 1976, the first one thous<strong>and</strong> feet are divided into sections <strong>of</strong> 100<br />

feet each. Although the content is highly integrated, each section was designed by a different artist under<br />

the general supervision <strong>of</strong> Judith Baca. Many problems were encountered in the beginning. Until the Mural<br />

Makers built a staircase down to the wash, people had to be trucked two <strong>and</strong> a half miles to the work site,<br />

bringing everything necessary with them, including water, food <strong>and</strong> restroom facilities. The entire mural area<br />

had to be s<strong>and</strong>bagged so that the residual water would not make the work area slippery. Several tons <strong>of</strong><br />

s<strong>and</strong> were trucked in, shoveled, bagged <strong>and</strong> then dragged into place.<br />

12

13<br />

Time Line <strong>and</strong> Sketches for Mural Planning

HOW IT IS DONE<br />

Each section takes a full year to research, organize, <strong>and</strong> execute. Youth <strong>of</strong> varied ethnic backgrounds<br />

between the ages <strong>of</strong> 14 <strong>and</strong> 21 must be recruited <strong>and</strong> interviewed. Those selected are employed as assistants<br />

<strong>and</strong> participate in both the planning <strong>and</strong> execution <strong>of</strong> the mural. These Mural Makers, mostly from low-income<br />

families, are paid through the Summer Youth Employment Program. In 1981 <strong>and</strong> 1983 additional youth were<br />

hired through a grant from the Jewish Community Foundation. Funds must be raised, research begun, <strong>and</strong><br />

artist supervisors hired. Pr<strong>of</strong>essional artists work with youth four to eight hours a day. They also receive art<br />

instruction, attend lectures from historians specializing in ethnic history, do improvisational theater <strong>and</strong> teambuilding<br />

exercises <strong>and</strong> acquire the important skill <strong>of</strong> learning to work together in a context where the diversity<br />

<strong>of</strong> their cultures is the focus.<br />

After the subjects to be included are selected <strong>and</strong> sketched, Baca makes finished designs along with a<br />

team <strong>of</strong> artists <strong>and</strong> youth selected to work under her direction on the “design team”. The finished drawings<br />

are blueprinted or turned into large drawings for pounce transfers. On site work begins with heavy labor:<br />

S<strong>and</strong>blasting, waterblasting <strong>and</strong> sealing the surface. Grid lines are marked on the <strong>wall</strong> to match those on<br />

the blueprints, <strong>and</strong> the images are transferred; a process that provides on-the-job math (as well as drawing)<br />

training for the kids. After the lines are drawn <strong>and</strong> painted a dark blue, a transparent magenta undercoat is<br />

applied over the entire surface. This serves to harmonize the colors as well as to cut the glare <strong>of</strong> the sunlight<br />

in the painter’s eyes. Snow blindness is a real hazard for the team on the massive <strong>wall</strong>. The colors are applied<br />

first as flat areas <strong>and</strong> then highlighted <strong>and</strong> shaded with two tones <strong>of</strong> the same “color-tri-color blends,” as the<br />

painters call it. Finally, a clear acrylic sealer is applied to protect the painting.<br />

14

1976 PROJECT:<br />

THE FIRST 1000 FT<br />

15<br />

Painted during the first summer <strong>of</strong> work in 1976,<br />

the first one thous<strong>and</strong> feet are divided into<br />

sections <strong>of</strong> 100 feet each. Although the content<br />

is highly integrated, each section was designed<br />

by a different artist under the general supervision<br />

<strong>of</strong> Judith Baca. Many problems were<br />

encountered in the beginning. Until the<br />

Mural Makers built a staircase down to the wash,<br />

people had to be trucked two <strong>and</strong> a half miles<br />

to the work site, bringing everything necessary<br />

with them, including water, food <strong>and</strong> toilets. The<br />

entire mural area had to be s<strong>and</strong>bagged so<br />

that the residual water would not make the work<br />

area slippery. Several tons <strong>of</strong> s<strong>and</strong> were trucked<br />

in, shoveled, bagged <strong>and</strong> then dragged<br />

into place.

16<br />

Great Wall Youth Crew, 1976

17<br />

Pre-Historic Portion <strong>of</strong> Mural in Progress

PRE HISTORIC CALIFORNIA<br />

The initial segment, designed by Kristi Lucas, begins in 20,000 BC, when the animals whose bones were<br />

found in the La Brea Tar Pits still w<strong>and</strong>ered among the plants <strong>and</strong> trees native to the area. In their<br />

research, the Mural Makers discovered that many <strong>of</strong> the trees we think <strong>of</strong> as typically Californian, such<br />

as the Eucalyptus <strong>and</strong> Pepper, were brought by settlers. By 10,000 BC, the Chumash Indian peoples had<br />

settled in this region having migrated, most likely by way <strong>of</strong> a l<strong>and</strong> bridge. They had a special relationship<br />

to <strong>and</strong> respect for the animals, especially porpoises. These are shown both in their natural environment<br />

<strong>and</strong> at the center <strong>of</strong> the prayer wheel, which forms the transition to the second segment. Designed by<br />

Christina Schlesinger, this section provides an overview <strong>of</strong> Chumash practical <strong>and</strong> spiritual life as it might<br />

have been in 1000 BC. A vision in which human <strong>and</strong> animal spirits mingle expresses Chumash religious<br />

sentiments. Much <strong>of</strong> this section was painted by an American Indian boy who shares this worldview. The<br />

peaceful early history <strong>of</strong> the region ends with a White h<strong>and</strong> rising from the sea, a symbol <strong>of</strong> the destruction<br />

<strong>of</strong> Native American life by White settlers.<br />

18

19<br />

Judy Baca on Scafolding, 1976

SPANISH ARRIVAL<br />

The arrival <strong>of</strong> the Spanish explorer Portillo, who brought the first expedition from Mexico to L.A. in 1769, begins<br />

the third segment, designed by Judith Baca. The figures in the clouds <strong>of</strong> smoke that rise from the Indian<br />

campfires represent Califia, the legendary Black Amazon Queen who Portillo expected to find <strong>and</strong> for whom<br />

California is named. Further on, riding a mule, Father Junipero Serra arrives. Founder <strong>of</strong> missions throughout<br />

California, he is depicted with the San Fern<strong>and</strong>o mission behind him. Within a year after the arrival <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Spaniard, a large percentage <strong>of</strong> the 150,000 Native American inhabitants had died <strong>of</strong> diseases brought over<br />

by the Europeans. For this reason, the San Fern<strong>and</strong>o Mission became known to the Indians as the “House <strong>of</strong><br />

Death.”<br />

It is commonly believed that the founders <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles were Spanish. However, on September 4, 1781,<br />

El Pueblo de la Reina de Los Angeles was founded by 46 pobladores from Mexico, only two <strong>of</strong> whom were<br />

Spanish. The majority were Indian, Meztiso, Mulatto <strong>and</strong> Black.<br />

Mexico governed California until 1848. In February <strong>of</strong> that year, Mexico signed the Treaty <strong>of</strong> Guadalupe<br />

Hidalgo, selling the Mexican Cession, including all <strong>of</strong> California, to the United States for $15 million. The fourth<br />

segment, designed by Judith Hern<strong>and</strong>ez, is dominated by the figure <strong>of</strong> a Spanish l<strong>and</strong> baron, illustrating the<br />

“hacendados” who dominated early California. His serape is formed by the l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> labor <strong>of</strong> the Indians,<br />

which he has taken <strong>and</strong> used to build the hacienda. He looks toward this hacienda where an elegant<br />

wedding is taking place. The panel begins with soldiers who raise the Spanish flag <strong>and</strong> ends with the battle<br />

between the Mexican army <strong>and</strong> the U.S. cavalry for the control <strong>of</strong> California.<br />

20

1848 BANDAID<br />

The Gold Rush era, as designed by Ulysses Jenkins, provides a Black-American perspective on this period. It<br />

begins with the discovery <strong>of</strong> gold at Sutters’ Mill <strong>and</strong> the subsequent migration <strong>of</strong> Blacks, Mexicans, Indians,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Whites by ship to California. Above the bay are portraits <strong>of</strong> Mifflin W. Gibbs, publisher <strong>of</strong> the first Black<br />

newspaper <strong>and</strong> Mary Ellen Pleasant, a civil rights activist who helped defend Blacks arraigned under the<br />

fugitive slave laws. The globe represents the world’s desire for the riches <strong>of</strong> the 49ers. Beside it st<strong>and</strong>s William<br />

A. Leidesdorf, pilot <strong>of</strong> the first steamboat to arrive in San Francisco Bay, who later became a vice consul to<br />

Mexico.<br />

Meanwhile, though California entered the Union as a free state, the framers <strong>of</strong> the state constitution wrote<br />

into law the systematic denial <strong>of</strong> suffrage <strong>and</strong> other civil rights to non-white citizens. From this time until 1863,<br />

Indians <strong>and</strong> other non-whites could not testify against whites in California courts. During this time, Biddy<br />

Mason, an ex-slave from Georgia who fought extradition under the fugitive slave laws, became very wealthy<br />

<strong>and</strong> known for her charity. She was also a founder <strong>of</strong> the African Methodist Church in Los Angeles <strong>and</strong> is<br />

depicted in the mural. Joaquin Murrieta, a legendary Mexican Robin Hood is also depicted, fighting for the<br />

oppressed: The l<strong>and</strong>less who “squat” on the state; the “hanging tree” victims <strong>of</strong> prejudice; <strong>and</strong> the Indians<br />

who are slaughtered with the coming <strong>of</strong> the “Iron Horse.”<br />

22

SOJOURNERS<br />

The “Iron Horse” also brought a wave <strong>of</strong> Chinese immigration. Designed by Gary Takamoto, the Chinese<br />

segment shows the workers on the transcontinental railroad, which was built largely by Chinese labor. The<br />

faces, which appear in the smoke <strong>of</strong> the locomotive, honor those who died in the course <strong>of</strong> this mammoth<br />

undertaking. A surge <strong>of</strong> racism that accompanied Chinese immigration led to the death <strong>of</strong> 19 Chinese men<br />

<strong>and</strong> boys during the “Chinese Massacre” <strong>of</strong> 1871 when 500 non-Asian Angelinos stormed Chinatown to loot<br />

homes <strong>and</strong> businesses <strong>and</strong> to attack residents.<br />

The Woman’s Suffrage Movement also began at this time. This segment was designed by Olga Muniz.<br />

24

1890 L.A. MOUNTAINS TO THE SHORE<br />

Designed by American Indian artist Charlie Brown, “From the Mountains to the Shore” begins with San Pedro<br />

Harbor where, until recently, there was a <strong>great</strong> abundance <strong>of</strong> flying fish. In Los Angeles, the “Red Car”<br />

provided an early energy efficient form <strong>of</strong> transportation. A vast network <strong>of</strong> electric railway lines operated by<br />

the Pacific Electric (PE) blanketed the Los Angeles area with more than 1000 miles <strong>of</strong> rail lines. The typical shops<br />

<strong>and</strong> buildings <strong>of</strong> turn-<strong>of</strong>-the-century L.A. are depicted in this lyrical segment.<br />

The first summer’s work concluded with an homage to the new wave <strong>of</strong> immigrants <strong>and</strong> their labor, which was<br />

so important to the development <strong>of</strong> this region. Designed by Isabel Castro, the section begins with an image<br />

showing these new arrivals in a wave <strong>of</strong> flags that indicate their varied origins. The segment continues with the<br />

invention <strong>of</strong> the car <strong>and</strong> airplane, two vehicles that shaped the development <strong>of</strong> 20th century California.<br />

The first 1,000 feet were completed in nine weeks <strong>of</strong> painting. The names <strong>of</strong> all those who participated were<br />

stenciled onto the <strong>wall</strong>.<br />

26

1978 PROJECT<br />

27<br />

Many lessons were learned through the experience <strong>of</strong><br />

the first summer’s work. In looking back, Baca realized<br />

that, “In those first 1,000 feet, the mural [was] a loosely<br />

connected series <strong>of</strong> easel paintings.” Beginning in<br />

1978, she exerted more control over the design,<br />

which resulted in more stylistic unity <strong>and</strong> an evolving<br />

complexity both in the transitions between the sections<br />

<strong>and</strong> the linkages between historical incidents.

28<br />

Great Wall Youth Crew, 1978

WORLD WAR I<br />

Emphasis in this section is placed on women’s role in the war experience. Depicted are the “doughboys”<br />

as they leave for war, kissing their wives <strong>and</strong> girlfriends goodbye. In the recruiting poster, woman appears<br />

in her mythic form as the symbol <strong>of</strong> Liberty. In reality, she took on “men’s jobs” in manufacturing plants or<br />

contributed to the war effort through “women’s jobs” like nursing.<br />

As the war reached into every aspect <strong>of</strong> American life, Charlie Chaplin, the famous silent movie comedian<br />

<strong>and</strong> a symbol <strong>of</strong> the common man, threw his support behind World War I. He is represented in the mural as<br />

a typical “doughboy,” fighting in the trenches for the ideals in which he believes <strong>and</strong> for which the war was<br />

being fought. His presence also links the war section with the development <strong>of</strong> Hollywood <strong>and</strong> the movie<br />

industry.<br />

30

A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON EDISON<br />

In researching Thomas Alva Edison, inventor <strong>of</strong> the light bulb, the Mural Makers found much evidence to<br />

support the theory that Edison was born in Zacatecas, Mexico, <strong>and</strong> adopted by U.S. parents. According<br />

to Edison’s daughter, Madeline Edison Sloane, there is no birth record for her father in the United States. In<br />

addition, almost all American biographers <strong>and</strong> historians agree that Edison could speak, read <strong>and</strong> write<br />

Spanish as fluently as a native speaker even though he had only three months <strong>of</strong> formal education.<br />

Edison’s Mexican-American heritage is symbolized by the Chichimeca corn goddess who whispers the<br />

secrets <strong>of</strong> the ancient builders <strong>and</strong> inventors in his ear. In one h<strong>and</strong> he holds a light bulb that lights the world.<br />

In the other h<strong>and</strong> we see a movie camera, symbolizing the modern communications industry. Hollywood is<br />

celebrated in the final image <strong>of</strong> William S. Hart, star <strong>of</strong> the first cowboy movie ever made, “The Great Train<br />

Robbery.” The scene shows the movie actors on the set <strong>and</strong> also in the camera viewer.<br />

32

1980 PROJECT<br />

33<br />

In 1980 the crew consisted <strong>of</strong> some 40 youth, a group<br />

<strong>of</strong> historians who helped workshops <strong>and</strong> programs for<br />

the participants, <strong>and</strong> a team <strong>of</strong> five artists working<br />

under the supervision <strong>of</strong> Judith Baca. The last 1,050<br />

feet <strong>of</strong> the <strong>wall</strong>, painted in the summers <strong>of</strong> 1980,<br />

1981, <strong>and</strong> 1983, are more complex in design with<br />

more sophisticated linkages between sections. The<br />

increased aesthetic quality <strong>of</strong> the <strong>wall</strong> began to bring<br />

both national <strong>and</strong> international attention. Feature<br />

articles on the Great Wall appeared in Life Magazine,<br />

Art in America, Ms, <strong>and</strong> German news magazine, Der<br />

Spiegel. In October <strong>of</strong> 1981, the Wadsworth Atheneum<br />

in Hartford, Connecticut, provided the Great Wall with<br />

its “first museum show.” The mural was also the focus <strong>of</strong><br />

a segment <strong>of</strong> Bill Moyers “Creativity in America” public<br />

television series.

34<br />

Great Wall Youth Crew, 1980

ILLUSION OF PROSPERITY<br />

The temperance movement’s axe looses a river <strong>of</strong> whiskey from the barrels <strong>of</strong> booze that the gangsters,<br />

symbolized by an Al Capone figure, used to become rich <strong>and</strong> powerful, while flappers dance in an “illusion<br />

<strong>of</strong> prosperity.” During this heyday <strong>of</strong> jazz, racial discrimination against Blacks continued. Black musicians <strong>and</strong><br />

their audiences were not allowed in White hotels. But the Dunbar Hotel enabled them to stay <strong>and</strong> perform in<br />

Los Angeles. Above the musicians, between the hotel <strong>and</strong> a bank beginning to topple in the crash <strong>of</strong> 1929, a<br />

Black worker drinks from a fountain marked, “Colored Only.”<br />

36

CRASH AND DEPRESSION<br />

The Great Depression began with the stock market crash on October 29, 1929. But in spite <strong>of</strong> Hollywood’s<br />

depiction <strong>of</strong> prosperity <strong>and</strong> romance, this economic disaster was inevitable. It could not be hidden by the<br />

illusions produced by the movie industry. In the mural, while the unemployed sell apples <strong>and</strong> warm their<br />

h<strong>and</strong>s on a trash can fire, the marching feet <strong>of</strong> the unemployed lead directly into strikes against low wages.<br />

The strikers symbolize the beginnings <strong>of</strong> the militant union movement <strong>of</strong> the Thirties <strong>and</strong> show its brutal<br />

repression. Still victimized in the 20th century by invalid treaties, Native Americans were forced to sell two<br />

thirds <strong>of</strong> their l<strong>and</strong> to developers at 45 cents per acre. Additionally, three hundred <strong>and</strong> fifty thous<strong>and</strong><br />

Mexican-Americans were rounded up <strong>and</strong> shipped across the border in mass deportations.<br />

38

DUSTBOWL REFUGEES<br />

As Mexicans were deported, “Okies,” refugees from the Oklahoma dustbowl whose fields were destroyed<br />

by drought, began to provide a new source <strong>of</strong> cheap farm labor. These “Okies,” in spite <strong>of</strong> their misery,<br />

migrated by their own will. The following migration, that <strong>of</strong> the Japanese, was the result <strong>of</strong> a force; In the<br />

wake <strong>of</strong> the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, approximately 110,000 Japanese nationals <strong>and</strong><br />

Japanese Americans were relocated to internment camps. The problem <strong>of</strong> how to connect these two<br />

migrations puzzled the Mural Makers. Baca remembers asking her assistants, “What did the Okies <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Nisei have in common?” The answer: Laundry. Lines <strong>of</strong> hanging wash form a visual connection between<br />

these two sections.<br />

40

1981 PROJECT<br />

41<br />

The 1940’s section – painted in the summer <strong>of</strong> 1981 with a<br />

crew <strong>of</strong> 34 youth, six artist-supervisors <strong>and</strong> two designers<br />

(Judith Baca <strong>and</strong> Jan Cook) – began where the Thirties<br />

section ended: With the role <strong>of</strong> the Japanese-Americans<br />

during this period.

42<br />

Great Wall Youth Crew, 1981

WORLD WAR II<br />

The 442nd Japanese-American infantry division comes out <strong>of</strong> the stripes <strong>of</strong> the American flag, yet in the<br />

shadow <strong>of</strong> these stripes, Japanese-Americans move backward toward the internment camps depicted in<br />

the previous section, forced to discard their possessions as they go. The mural continues to explore, in turn,<br />

the contradictory situation <strong>of</strong> each <strong>of</strong> the other ethnic minorities in California. A Jewish-American family,<br />

in the shadow <strong>of</strong> Hitler’s h<strong>and</strong>, listens to the news from Europe. Hitler’s other h<strong>and</strong> makes a fist. From it,<br />

goosesteppers lead toward an anti-Fascist rally in Los Angeles <strong>and</strong> toward World War II. Below, on the home<br />

front, the California Aqueduct is built to transport water from north to south to aid developers, but creates a<br />

desert in the Owens Valley region. The World War II segment shows Jeanette Rankin in Congress below <strong>and</strong><br />

Pearl Harbor above. A group <strong>of</strong> generals <strong>and</strong> businessmen plan the war effort. From that cooperative effort<br />

streams the lines <strong>of</strong> soldiers, arms <strong>and</strong> women war workers.<br />

44

CHARLES DREW<br />

The war industry also provided jobs for black women workers. In the mural they are shown opening the doors<br />

to the war industry with Dr. Charles Drew, the inventor <strong>of</strong> large-scale blood banks. Dr. Drew is shown cradling<br />

himself in his own arms as he dies unnecessarily because <strong>of</strong> a southern hospital’s refusal to treat him for<br />

blood loss. The iron h<strong>and</strong>, symbolizing the dehumanization that racial discrimination brings, is shown cutting<br />

<strong>of</strong>f the flow <strong>of</strong> blood, ending life. Beyond these accomplishments <strong>of</strong> African Americans in the war industry,<br />

the mural depicts the discrimination that continued in housing. “We Fight Fascism At Home <strong>and</strong> Abroad,”<br />

commemorates the struggle by Mrs. Laws against the covenant laws that denied Blacks access to equal<br />

housing in South Central L.A.<br />

46

ZUIT SUIT RIOTS<br />

The contradictions in the Chicano experience are expressed by contrasting the experience <strong>of</strong> Chicano<br />

servicemen with the experience <strong>of</strong> those at home. David Gonzalez, a local Chicano Congressional Medal<br />

<strong>of</strong> Honor winner, is shown st<strong>and</strong>ing with his mother in a collage <strong>of</strong> photos from a family album. In the next<br />

panel, we see the “Zoot Suit Riots,” a series <strong>of</strong> riots that erupted in Los Angeles during World War II, between<br />

white Marines stationed throughout the city <strong>and</strong> Latino youths. Mexican-American boys wearing Zoot Suits<br />

were stripped <strong>and</strong> beaten by marines with the consent <strong>of</strong> the police. Also depicted, trains carry “braceros,”<br />

Mexican farm workers, contracted to work temporarily in the California farm fields. The struggle to organize<br />

the farm workers <strong>and</strong> dem<strong>and</strong>s for more humane working conditions are represented by the portrait <strong>of</strong> labor<br />

organizer Luiso Moreno, who is wrapped in the flag <strong>of</strong> the Congress <strong>of</strong> Hispanic Groups.<br />

48

JEWISH REFUGEES<br />

Parallel to the train bringing migrant workers, the St. Louis – a Jewish-European immigrant ship that was<br />

refused entry to the U.S. because the Jewish immigration quota was already met – is painted. The spirit<br />

<strong>of</strong> these starved <strong>and</strong> suffering Jewish victims <strong>of</strong> the Holocaust emerges from the ship <strong>and</strong> reaches for<br />

American soil. Behind we see the death camps where the Germans murdered more than six million Jews.<br />

Beyond the death camps is the mushroom cloud <strong>of</strong> the Atomic Bomb, another symbol <strong>of</strong> death, <strong>and</strong><br />

beyond that the founding <strong>of</strong> Israel <strong>and</strong> the greening <strong>of</strong> the desert. The end <strong>of</strong> the War brought about a<br />

wave <strong>of</strong> prosperity, the development <strong>of</strong> tract homes, <strong>and</strong> the baby boom. In the kitchen <strong>of</strong> a typical tract<br />

house in the San Fern<strong>and</strong>o Valley (the rest <strong>of</strong> the development can be seen through the window) we see<br />

a baby scream. On the television, Ronald Reagan stars in a 1940’s era war movie. Outside, peering at the<br />

“American Dream” through the plate glass windows, soldiers <strong>of</strong> color discover that little has changed for<br />

them on their return.<br />

50

1983 PROJECT<br />

51<br />

The 1950’s section was painted in the summer <strong>of</strong><br />

1983 with a crew <strong>of</strong> 30 youth, seven artist supervisors,<br />

<strong>and</strong> muralist/director Judith Baca. This 350-foot<br />

segment attained sponsorship from such groups as<br />

the National Endowment <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Arts</strong>, the California<br />

Council for the Humanities, the Los Angeles Olympic<br />

Organizing Committee <strong>and</strong> numerous other groups<br />

<strong>and</strong> individuals. With the aid <strong>of</strong> over a dozen humanist<br />

scholars <strong>and</strong> historians, workshops <strong>and</strong> programs<br />

were held for the muralists in selecting, designing <strong>and</strong><br />

enlivening the images.

52<br />

Great Wall Youth Crew, 1983

FAREWELL TO ROSIE THE RIVETER<br />

During World War II, millions <strong>of</strong> American women left their traditional roles as housewives <strong>and</strong> entered the<br />

industrial market as manual laborers <strong>and</strong> managers. But in the post-war years, “Rosie the Riveter” returned<br />

to the kitchen as the men returned home <strong>and</strong> reclaimed their power <strong>and</strong> position in labor. Women’s<br />

access to work positions traditionally dominated by men was revoked. The television set depicted in this<br />

segment propagates mass social images <strong>of</strong> the housewife <strong>and</strong> a workingwoman being sucked into the<br />

T.V. image.<br />

54

DEVELOPMENT OF SUBURBIA<br />

Behind the televised images <strong>of</strong> American womanhood, an all-American family <strong>of</strong> 2.5 kids (The .5 represented<br />

by “Howdy Doody”) moves into a new suburb <strong>of</strong> endless box houses in endless rows. These boxes represent<br />

“white flight,” a demographic trend in which white people move away from urban neighborhoods that are<br />

becoming racially desegregated to white suburbs <strong>and</strong> exurbs. Meanwhile, minorities <strong>and</strong> poor immigrants<br />

move from rural communities into the city. Rows <strong>of</strong> orange trees have been uprooted as suburbs sprawl<br />

throughout the L.A. basin <strong>and</strong> valleys.<br />

56

THE RED SCARE AND MCCARTHYISM<br />

Joseph McCarthy, the infamous prosecutor during the second “Red Scare,” holds up a blacklist, naming<br />

film industry people who are accused <strong>of</strong> being Communist activists <strong>and</strong> sympathizers. The “Hollywood Ten,”<br />

a group <strong>of</strong> Hollywood producers, directors, writers <strong>and</strong> actors, are subpoenaed <strong>and</strong> found in contempt<br />

<strong>of</strong> Congress for refusing to answer McCarthy’s charges by naming names (it was not enough to admit to<br />

being a communist at this time. One had to also incriminate one’s friends <strong>and</strong> colleagues by providing their<br />

names.). These ten, as well as others, were blacklisted <strong>and</strong> shunned, their pr<strong>of</strong>essional <strong>and</strong> personal lives<br />

destroyed. A typewriter, tied <strong>and</strong> bound by the lists, represents the fear <strong>of</strong> being blacklisted <strong>and</strong> the denial <strong>of</strong><br />

5th Amendment rights. In the background, Sputnik hovers over the scene, reminding the viewer <strong>of</strong> the Soviet<br />

Union’s techno-military progress which startles <strong>and</strong> frightens America.<br />

58

CHAVEZ RAVINE AND THE DIVISION OF THE CHICANO COMMUNITY<br />

In the 1940s, Chavez Ravine was a poor, though cohesive, Mexican-American community. But in the early<br />

50’s, the Housing Authority <strong>of</strong> the City <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles labeled the area as “blighted” <strong>and</strong> began relocating<br />

residents so that the area could be redeveloped to include Dodger Stadium. In many parts <strong>of</strong> LA, new<br />

freeways began to encircle <strong>and</strong> dislocate various areas, effectively dividing minority communities. In this<br />

panel, serpentine thoroughfares separate a Chicano family as the pillared highway breaks through the ro<strong>of</strong>s<br />

<strong>of</strong> houses. Resembling a massive UFO, Dodger Stadium descends from the twilight sky into Chavez Ravine.<br />

A bulldozer <strong>and</strong> policemen forcibly uproot the Chicano community so that Dodger Stadium can be built<br />

on l<strong>and</strong> designated at one time for public housing. Many individuals resisted this forced eviction from their<br />

neighborhood, but to no avail.<br />

60

THE BIRTH OF ROCK AND ROLL<br />

Pop 50’s culture is captured in this scene at a drive-in theater. A huge Elvis Presley wails his rock songs from<br />

the silver screen, but behind him a smaller image <strong>of</strong> Chuck Berry acknowledges the original force <strong>of</strong> rock’s<br />

creativity <strong>and</strong> inspiration in the Black community. Various hotrods <strong>and</strong> low-riders face the screen, as a starspeckled<br />

sky forms the background. Behind Elvis <strong>and</strong> the movie screen, Black musicians again represent the<br />

spirit <strong>and</strong> contribution <strong>of</strong> the Black community to popular culture. Jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker <strong>and</strong> Blues<br />

vocalist Big Mama Thornton (who wrote “Ain’t Nothin’ But A Hound Dog” which Elvis popularized without<br />

crediting her) perform. Behind these Black musicians, a Charles White portrait <strong>of</strong> a Black woman holding up<br />

South L.A. portrays the sustaining community activism <strong>of</strong> Black women in volunteer <strong>and</strong> church organizations.<br />

This scene emerges with another depiction <strong>of</strong> the interior <strong>of</strong> a local bus. Paul Robeson, Rosa Parks, Gwendolyn<br />

Brooks, Ralph Bunche <strong>and</strong> Martin Luther King, Jr., rise from their bus seats <strong>and</strong> move forward for new<br />

destinations: the Civil Rights movement.<br />

62

ORIGINS OF THE GAY RIGHTS MOVEMENT<br />

The 1950’s witnessed the emergence <strong>of</strong> homosexual community organizing, represented in this panel by<br />

the first gay/lesbian publications <strong>and</strong> social change organizations. As police enter the closet to repress<br />

the homosexual community through violence <strong>and</strong> entrapment, women forming the first lesbian rights<br />

organization, the “Daughters <strong>of</strong> Bilitis,” meet in a kitchen <strong>and</strong> mimeograph copies <strong>of</strong> their newsletter, “The<br />

Ladder.” These newsletters float out <strong>of</strong> the closet above the heads <strong>of</strong> the police. In a gay bar, solitary men<br />

sit in front <strong>of</strong> mirrors, cautiously glancing at one another, fearing entrapment by vice <strong>of</strong>ficers. Each wears a<br />

mask at the back <strong>of</strong> his head symbolizing the false front to society that gays had to assume in order to avoid<br />

persecution. In the mirror, the men see themselves as they wish they could be-warm, affectionate, caring.<br />

The masks also represent the Mattachine Society, founded in 1950 by, amongst others, Harry Hay, depicted<br />

here issuing his call to organize. Inspired by the masked Mattachine male dancers <strong>of</strong> medieval France, the<br />

Mattachine Society was the first to advocate social equality for homosexuals.<br />

64

THE BEATS<br />

In this panel, the Beat movement represents another controversial underground movement. The major<br />

works <strong>of</strong> Beat writing are Allen Ginsberg’s Howl (1956), William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch (1959) <strong>and</strong> Jack<br />

Kerouac’s On the Road (1957). Various Venice cafes sponsored Beat jazz sessions, abstract art exhibitions<br />

<strong>and</strong> poetry readings. But disgruntled conservatives moved to halt these activities <strong>and</strong> close the cafes,<br />

provoking Beats to protest.<br />

66

JEWISH ACHIEVEMENTS IN ARTS AND SCIENCE<br />

Just as Jewish writers like Allen Ginsberg took risks in developing a new creative movement, Jews in Los<br />

Angeles started out in high-risk businesses, which, by the 1950’s, had become among the most important<br />

in California. New York garment workers became recyclers <strong>of</strong> rags in Los Angeles <strong>and</strong>, eventually, the<br />

backbone <strong>of</strong> the garment industry. Also high risk in the 20’s was the fledgling film industry built by Jewish<br />

studio owners into highly successful enterprises. In the mural, a huge image <strong>of</strong> Albert Einstein holding a<br />

diagram <strong>of</strong> an atom reveals his concern that atomic power be used for peaceful purposes <strong>and</strong> not war.<br />

68

INDIAN ASSIMILATION<br />

In this ninth scene, the forced assimilation <strong>of</strong> Indians is depicted by a government <strong>of</strong>ficial stripping an Indian<br />

boy <strong>of</strong> his traditional dress <strong>and</strong> cutting his hair. Indian youth were sent several states away from their homes to<br />

boarding schools where they were taught to give up their traditional culture for Anglo ways. Concurrent with<br />

this program was the urban relocation <strong>of</strong> many other Indian adults <strong>and</strong> children <strong>of</strong>f <strong>of</strong> reservations.<br />

70

ASIANS GAIN CITIZENSHIP AND PROPERTY<br />

Despite harsh immigration quotas, Asian Americans made progress in the Fifties by attaining naturalization<br />

<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> ownership rights. In this panel a civilian is sworn in as the first Korean to be granted American<br />

citizenship. Behind the scene, a Japanese farmer st<strong>and</strong>s proud in his newly purchased field, depicting the<br />

gains <strong>of</strong> Japanese Americans also to become citizens <strong>and</strong> to own l<strong>and</strong>.<br />

72

OLYMPIC CHAMPIONS 1948-1964<br />

In this final panel, a woman runner carries the Olympic torch, its flame <strong>and</strong> smoke swirling into scenes <strong>of</strong> athletes<br />

who overcome tremendous obstacles to win Olympic events. Billy Mills, a Dakota 0glala marathon runner,<br />

overcame his suppression in boarding schools to become an important symbol for Native American pride.<br />

Black runner Wilma Rudolf, overcoming her childhood infirmities (being unable to walk until her eighth birthday)<br />

throws away her leg braces <strong>and</strong> becomes the first American to win three gold medals. Sammy Lee, a Korean<br />

American diver, <strong>and</strong> Vicky Manalo Droves, a Filipina diver, win gold medals as well. The symbolic final runner<br />

carries the torch <strong>of</strong> the 1950’s into the civil rights movements <strong>of</strong> the 1960’s.<br />

74<br />

Sketch <strong>of</strong> Olympic Winners for portion <strong>of</strong> the Great Wall

GREAT WALL<br />

TESTIMONIALS<br />

75<br />

On the last day <strong>of</strong> the 1983 summer project, each<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Mural Makers sat down to write about their<br />

experiences <strong>of</strong> working on the mural. The following are<br />

excerpts from their thoughts.

MURAL MAKER TESTIMONIALS<br />

This was definitely not a waste <strong>of</strong> my time. I feel I<br />

have accomplished something very worthwhile. I<br />

have educated myself with the work I have done I<br />

will help to educate countless others. I have never<br />

been involved with the creating <strong>of</strong> a l<strong>and</strong>mark before,<br />

but if I had a choice <strong>of</strong> any the mural is the one I<br />

would choose. The fact that this mural is recognized<br />

internationally is very exciting <strong>and</strong> has fulfilled my<br />

dream <strong>of</strong> doing something with international impact.<br />

I’m not just a Mural Maker, I’m a history maker <strong>and</strong><br />

proud <strong>of</strong> the history on the <strong>wall</strong> I got the chance to<br />

show.<br />

Kelly Watts, age 19<br />

Third summer on the project<br />

If I can come back next year I would come back right<br />

away. I have a lot <strong>of</strong> feeling that I can’t explain on<br />

paper. All I can say is I wish everybody the best <strong>of</strong> luck<br />

in the future <strong>and</strong> I wish Judy all the success that she<br />

needs to continue.<br />

Robert Martinez, age 18<br />

Third summer on the project<br />

It’s been <strong>great</strong> working at the Great Wall <strong>and</strong> having<br />

76<br />

a large family <strong>of</strong> forty. I bet you can’t top that I’ve<br />

learned to get along with people <strong>of</strong> all colors <strong>and</strong> the<br />

responsibility <strong>of</strong> doing for myself. I would do it again.<br />

But it was not all fun <strong>and</strong> play. It takes time to get<br />

things all together. But still in all, the best part is getting<br />

to the end <strong>and</strong> looking back<br />

at what you helped do.<br />

Rena Robinson, age 17<br />

First summer on the project<br />

To me the mural means a piece <strong>of</strong> art, it means<br />

workmanship among others, it means a part <strong>of</strong><br />

ourselves, also making new friends, doing a good job<br />

<strong>and</strong> having lots <strong>of</strong> fun.<br />

Alex Alvarez, age 14<br />

First summer on the project<br />

There’s one way to describe our worksite <strong>of</strong> people<br />

<strong>and</strong> that is we’re on Big Family <strong>and</strong> I hope when the<br />

public comes to admire our mural they’ll share the<br />

magic <strong>and</strong> emotion that our crew shared with one<br />

another.<br />

Nancy Jane Avila, age 17<br />

First summer on the project

In today’s society where there’s not many<br />

constructive <strong>and</strong> positive activities or happenings, this<br />

mural is a very positive thing. Where else can kids from<br />

all kinds <strong>of</strong> cultural backgrounds come together <strong>and</strong><br />

work towards a goal. I have found this<br />

experience to be very rewarding <strong>and</strong> got a lot out<br />

<strong>of</strong> it. The work was very hard at times but the finishing<br />

product was well worth the effort, you know, the end<br />

justifying the means. There were times when I had my<br />

bad days but mostly they were <strong>great</strong>. I’m very proud<br />

that I worked on the mural this year <strong>and</strong> if there’s any<br />

way possible I would more than happily come back<br />

next year. It got to the point where I didn’t’ care if I<br />

was getting<br />

paid or not, but the pay was nice to get for it. It’s<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> neat knowing that you’re becoming a part <strong>of</strong><br />

history <strong>and</strong> that it’s a community project that people<br />

will appreciate.<br />

Michelle Russell, age 21<br />

First summer on the project<br />

77<br />

This was my second year on the mural, but it was a<br />

completely new experience. The group feeling was<br />

tremendous, stronger sooner than two years ago. This<br />

year had obstacles that weren’t present previously,<br />

<strong>and</strong> this unity kept us going because we were so<br />

proud <strong>of</strong> our unity that the idea <strong>of</strong> giving up after the<br />

flood <strong>and</strong> splitting the crew, was inconceivable. After<br />

my first year on the mural, I left with a sense <strong>of</strong> who I<br />

was <strong>and</strong> what I could do that was unlike anything I’d<br />

ever felt before. The feeling came from encountering<br />

people <strong>of</strong> different backgrounds <strong>and</strong> outlooks, <strong>and</strong><br />

confronting history from new perspectives, <strong>and</strong> seeing<br />

what I was personally capable <strong>of</strong> at a time<br />

in my life when my self0confidence had been<br />

extremely low. This year was different largely because<br />

I had been changed by my earlier experience on the<br />

mural. The feelings <strong>of</strong> identity <strong>and</strong> pride came in new<br />

ways. Because <strong>of</strong> the unity we share, I feel now that<br />

everything on the mural is my history, in a deeper way<br />

than I think I felt before.<br />

Todd Ableser, age 18<br />

Second summer on the project

Being a crew leader <strong>and</strong> all, it gave me responsibility<br />

<strong>and</strong> an incentive to perform the<br />

desired duties to its full extent. It was hard to ask a<br />

friend to do a difficult job but in time everything fell<br />

into place. I want this mural to continue forever. I<br />

hope we paint in the summer <strong>of</strong> 1984 <strong>and</strong> every year<br />

after. I was a born surfer <strong>and</strong> I gave up the beach for<br />

the project <strong>and</strong> I will always be dedicated<br />

Marc Meisels, age 18<br />

This year has definitely been a year to remember, with<br />

the accident <strong>of</strong> the weather <strong>and</strong> the media. But in the<br />

end we pulled through. Everyone now seems to know<br />

the spirit <strong>of</strong> unity; sharing, caring <strong>and</strong> working it out.<br />

Esther Martinez, age 19<br />

Third summer on the project<br />

The mural project is composed <strong>of</strong> a group <strong>of</strong> young<br />

people working toward one mutual goal: the<br />

completion <strong>of</strong> a work <strong>of</strong> art from which will come<br />

<strong>and</strong> in-depth look to the drama <strong>and</strong> importance <strong>of</strong><br />

many <strong>great</strong> persons who have worked toward the<br />

banishment <strong>of</strong> racial injustice, discrimination <strong>and</strong><br />

human struggle. These are goals that we, as Mural<br />

Makers, see daily working on the mural. There is a<br />

feeling <strong>of</strong> camaraderie <strong>and</strong> friendship among the<br />

persons. Out <strong>of</strong> this bond shall be initiated another<br />

78<br />

strong addition to the Great Wall.<br />

Glenn Cho, age 16<br />

First summer on the project<br />

When I started working here I did it for the money,<br />

then began to take <strong>great</strong> pride in the mural <strong>and</strong> in<br />

the Chicano section in particular. At first I didn’t think<br />

an assortment <strong>of</strong> races could work together because<br />

in my neighborhood there is primarily one race. This<br />

project made me realize that the prejudices I had<br />

inside me were not only false but also ignorant. I<br />

only wish all mankind could have gone through this<br />

experience with me. I regret that when I leave here<br />

my new attitude will change back to before. I hope<br />

that when people see this mural they forget all their<br />

prejudices <strong>and</strong> try to live with all people, no matter<br />

what race, in peace.<br />

Sergio Moreno, age 16<br />

First summer on the project

THE ERNESTINE JIMENEZ STORY<br />

It was with this project that Ernestine became part <strong>of</strong> the SPARC alumni. Ernestine’s story is a testament to the<br />

value <strong>of</strong> our work <strong>and</strong> epitomizes so many similar stories over the years <strong>of</strong> how our work in community <strong>and</strong><br />

bringing art to the lives <strong>of</strong> young people has truly made a difference:<br />

As a young girl <strong>of</strong> 14 years, on PCP <strong>and</strong> pregnant, Ernestine desperately needed an outlet from her troubling<br />

environment. She met our Founder/Artistic Director Judy Baca who immediately knew that Ernestine<br />

could benefit from the experience <strong>of</strong> working with other young people <strong>and</strong> at the same time be part <strong>of</strong> a<br />

monumental cultural l<strong>and</strong>mark. Ernestine spent five significant years on the project <strong>and</strong> at the end became<br />

a crew leader. She has shared the story many times <strong>of</strong> how Judy Baca <strong>and</strong> the Great Wall project helped<br />

change her life those many years ago.<br />

In June <strong>of</strong> 2001, a film crew was in Los Angeles to do a story on Judy Baca, who was being honored as<br />

Educator <strong>of</strong> the Year from the Kennedy Center/Hispanic Heritage Awards in Washington D.C. This story would<br />

be televised nationally <strong>and</strong> we brought together people whose lives were touched by Judy <strong>and</strong> SPARC’s<br />

work. Ernestine was one <strong>of</strong> the people we chose to have interviewed. The interview took place at the Great<br />

Wall <strong>and</strong> Ernestine brought her son Rudy with her (with whom she was pregnant when she began working on<br />

the Great Wall). Ernestine gave a very moving interview, which aired in September 2001. Segments <strong>of</strong> the<br />

interview follow below, in her own words:<br />

80

The way I grew up was, you know you fight through life, you know, I got ten brothers <strong>and</strong> six sisters, <strong>and</strong> I’m the<br />

baby, <strong>and</strong> There was a fight in my house all time. And that’s the way I believed you were suppose to have<br />

grown up, to fight through life. Don’t like nobody but your own race, <strong>and</strong> even sometimes don’t even like your<br />

own race.<br />

There was a lot <strong>of</strong> tension, um; I think everyone wanted to fight every body; just the way they looked, or looked<br />

at them, or the way they dressed. After time you just started getting to know that person as an individual<br />

instead <strong>of</strong> knowing them as you were taught to, you know. And, everybody became very good friends. It took<br />

a lot a lot <strong>of</strong> growing up. I’m not saying that first year did it, cuz it didn’t. It took a lot <strong>of</strong> growing up. But I made<br />

a lot <strong>of</strong> friends through the four years <strong>and</strong> every year I understood something else, every year.<br />

I wouldn’t have went back to high school because I wouldn’t have had a role model to push me to go there.<br />

Education was Judy’s number one thing. As long as I stood in school, “you can come back <strong>and</strong> paint the<br />

mural”. Even though I got in trouble in school <strong>and</strong> fought <strong>and</strong> everything that was my number one goal. I<br />

wanted to come back. I had to come back.<br />

What really kind <strong>of</strong> freaked me out though, was when I met the people that when we painted the mural <strong>of</strong> the<br />

holocaust, <strong>and</strong> I met the people that had the tattoos on them, that kind <strong>of</strong> blew my mind. That actually made<br />

me cry because I knew there was another world that was harder than mine. And, I just really felt for it.<br />

This mural opened my eyes so much. Even when I’m down <strong>and</strong> out, I still walk by here. And I thank god I did<br />

accomplish something in life. It makes me feel good. I think if it wasn’t for this mural, for me to have my name<br />

on it <strong>and</strong> to have accomplished something, I don’t know where I’d be.<br />

81

GREAT WALL FUTURE<br />

82<br />

In 2000 <strong>and</strong> 2001 SPARC received<br />

acknowledgement <strong>and</strong> support from the Ford<br />

Foundation’s Animating Democracy: The Role <strong>of</strong><br />

Civic Dialogue in the <strong>Arts</strong> initiative <strong>and</strong> from the<br />

Rockefeller Foundation Partnership’s Affirming<br />

Community Transformation initiative to continue<br />

work on the Great Wall, to hold civic dialogue<br />

sessions, <strong>and</strong> to ultimately design the four decades<br />

<strong>of</strong> the 20th century that remain absent from the<br />

mural (the 1960, 1970, 1980 <strong>and</strong> 1990s). In 2006,<br />

SPARC was awarded with a California Cultural<br />

<strong>and</strong> Historical Endowment grant as well as a grant<br />

from the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy<br />

to acquire <strong>and</strong> develop a new solar-lit bridge with<br />

interpretive stations, to construct five additional<br />

interpretive stations along the <strong>wall</strong>, to design the<br />

next four decades (60’s, 70’s, 80’s, & 90’s), <strong>and</strong> to<br />

develop conservation education programs.

83<br />

Digital Model for the new Green Bridge over the L.A, River

INTERPRETIVE STATIONS<br />

SPARC has collaborated with Kulapat Yantrasast <strong>and</strong> Yo-ichiro Hakomori <strong>of</strong> wHY <strong>Architecture</strong> to complete<br />

the designs for a “Green Bridge” which will be solar lit <strong>and</strong> composed in part from the debris <strong>of</strong> the Los<br />

Angeles River with interpretive panels along the expanse <strong>of</strong> the Bridge from which the public can view the<br />

River <strong>and</strong> the ½ mile <strong>of</strong> mural along its banks.<br />

The new Great Wall <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles Interpretive Green Bridge will replaces a former bridge crossing the<br />

Tujunga Wash Flood control Channel. The bridge is in the same location between Mir<strong>and</strong>a Street <strong>and</strong><br />

Hatteras Street on the west side <strong>of</strong> the Coldwater Canyon Blvd. The new bridge functions, not only as a<br />

point to cross the Tujunga wash but also as a viewing station <strong>and</strong> interpretive center to underst<strong>and</strong> the<br />

significance <strong>of</strong> the Great Wall <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles mural <strong>and</strong> the Los Angeles River.<br />

The structure <strong>of</strong> the bridge will be built substantially from trash salvaged from the river itself; concrete <strong>wall</strong>s<br />

cast with bottle glass, cans, styr<strong>of</strong>oam, dirt <strong>and</strong> debris; floor <strong>and</strong> pavement made from recycled tires; bridge<br />

guardrail made from recycled parts <strong>of</strong> shopping carts scattered in the riverbed as a symbol <strong>of</strong> regeneration<br />

<strong>and</strong> sustainable design. Photovoltaic panels on the canopy will generate electricity for lighting at night.<br />

The total impact <strong>of</strong> the bridge is that it serves as an instructional site about the river <strong>and</strong> the history <strong>of</strong> the<br />

diverse people <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles while it reconnects the two sides <strong>of</strong> the channel.<br />

84

85<br />

Sketch for 1960s portion, created by UCLA class

NEW DESIGNS FOR THE 1960s - THE 1990s<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Judy Baca <strong>and</strong> her UCLA class are currently constructing designs for the next four decades <strong>of</strong><br />

the “Great Wall <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles” in the UCLA Cesar Chavez Digital Mural Lab. Classes focus research <strong>and</strong><br />

designes on seminal literature, art, film, key issues, historical events <strong>and</strong> popular culture characterized each<br />

<strong>of</strong> the decades: 1960, 1970, 1980, <strong>and</strong> 1990. Students develop time lines, identify imagery, gather oral histories<br />

<strong>and</strong> family photos from community members, <strong>and</strong> design <strong>and</strong> design the new portions collaboratively.<br />

The students explore muralism as a method <strong>of</strong> representation, community education, development <strong>and</strong><br />

empowerment.<br />

86

Map.....<br />

87

FURTHER INFORMATION<br />

ON THE GREAT WALL<br />

88

LOCATIONS<br />

Directions to THE GREAT WALL<br />

The Great Wall <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles is located in the San Fern<strong>and</strong>o Valley on Coldwater Canyon, between<br />

Burbank Boulevard <strong>and</strong> Oxnard Boulevard in Valley Glen, CA. Exit the 101 Freeway going North on<br />

Coldwater Canyon.<br />

Directions to SPARC<br />

SPARC is located at the Historic Venice Jail, adjacent to the Historic City Hall <strong>and</strong> the Venice Fire Station,<br />

between Lincoln <strong>and</strong> Abbott Kinney.<br />

SPARC RESOURCES<br />

Other tools to learn about the Great Wall <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles include the Great Wall <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles DVD <strong>and</strong><br />

Custom Tours. For more information please contact SPARC.<br />

MAKE HISTORY<br />

The history you have seen depicted in the mural is little known <strong>and</strong> not <strong>of</strong>ten portrayed in popular<br />

images. You can help make this history live for thous<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> people by joining the hundreds <strong>of</strong> Great Wall<br />

supporters. Be a part <strong>of</strong> the longest mural in the world. To help preserve the Great Wall <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles<br />

consider making a tax- deductible donation to SPARC.<br />

89

CONTACT SPARC<br />

Social <strong>and</strong> Public Art Resource Center<br />

685 Venice Boulevard<br />

Venice, California 90291<br />

310.822.9560<br />

www.sparcmurals.org<br />

WALKING TOUR GUIDE CREDITS<br />

Copy:<br />

Production Coordination:<br />

Carlos Rogel<br />

Assistance:<br />

Sarah Brothers<br />

Design:<br />

Robin Gilliam<br />

Printing:<br />

90

92<br />

The Entire Great Wall <strong>of</strong> L.A. frm Pre-Hitory to the 1950s

© 2007, SPARC, All Rights Reserved