Download (23MB) - University of Salford Institutional Repository

Download (23MB) - University of Salford Institutional Repository Download (23MB) - University of Salford Institutional Repository

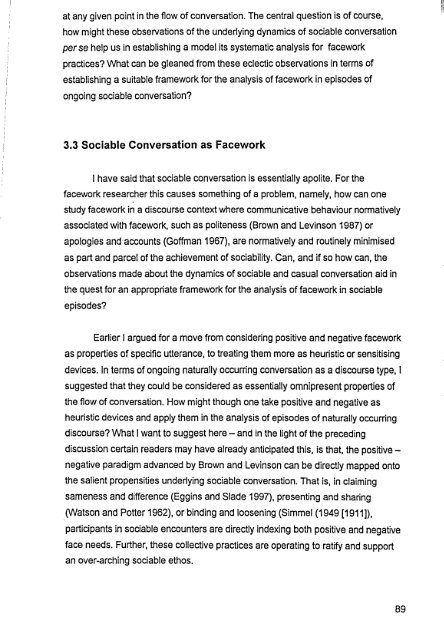

Fig. 3.3 The Interactional Motor of Casual Conversation Movement d comemeboraWsms v*my % trom e 'coi " Kw conim Difference Different/ autonomous selves I It = %% % =1 + Realisation of - Sameness Similar / soliclaric selves (I SI 4. Progression of conversation episodes Other work on sociable conversation further echoes these opposing moveftwm of convefsabonalists tDwards o'coff~ centre alignments taken by conversationalists. For example, drawing on Goffman's (1974) concept of 'frame', Schiffrin noted that Jewish speakers shifted suddenly from consensual to argumentative frames and back again during sociable conversation - what she termed sociable argumentation. Conversations essentially flitted unpredictably to and fro between these two opposing frames as part and parcel of sociable interaction. Finally, this work bears resemblances to conversational dynamics such as independence-involvement (e. g. Tannen 1984) and affiliative- idividuating styles (e. g. Malone 1997)'B. What this work might be boiled down to then is the fact that sociable conversation might be characterised by, indeed normatively require, a certain symbolic 'to-ing' and 'fro-ing' of participants, evidenced in their varying conversational expression of sameness and difference. Importantly, what has been alluded to is that these styles have a relationship to the self in talk as it is perceived RR

at any given point in the flow of conversation. The central question is of course, how might these observations of the underlying dynamics of sociable conversation per se help us in establishing a model its systematic analysis for facework practices? What can be gleaned from these eclectic observations in terms of establishing a suitable framework for the analysis of facework in episodes of ongoing sociable conversation? 3.3 Sociable Conversation as Facework I have said that sociable conversation is essentially apolite. For the facework researcher this causes something of a problem, namely, how can one study facework in a discourse context where communicative behaviour normatively associated with facework, such as politeness (Brown and Levinson 1987) or apologies and-accounts (Goffman 1967), are normatively and routinely minimised as part and parcel of the achievement of sociability. Can, and if so how can, the observations made about the dynamics of sociable and casual conversation aid in the quest for an appropriate framework for the analysis of facework in sociable episodes? Earlier I argued for a move from considering positive and negative facework as properties of specific utterance, to treating them more as heuristic or sensitising devices. In terms of ongoing naturally occurring conversation as a discourse type, I suggested that they could be considered as essentially omnipresent properties of the flow of conversation. How might though one take positive and negative as heuristic devices and apply them in the analysis of episodes of naturally occurring discourse? What I want to suggest here - and in the light of the preceding discussion certain readers may have already anticipated this, is that, the positive - negative paradigm advanced by Brown and Levinson can be directly mapped onto the salient propensities underlying sociable conversation. That is, in claiming sameness and difference (Eggins and Slade 1997), presenting and sharing (Watson and Potter 1962), or binding and loosening (Simmel (1949 [1911 ]), participants in sociable encounters are directly indexing both positive and negative face needs. Further, these collective practices are operating to ratify and support an over-arching sociable ethos. 89

- Page 47 and 48: Mao (1994) addresses this tension b

- Page 49 and 50: Tannen's work (1981 a; 1981 b) perh

- Page 51 and 52: 1.3 Culture, Facework, Equilibrium

- Page 53 and 54: facework operates on an underlying

- Page 55 and 56: CHAPTER 2 ANGLO-SAXON CHALK AND TEU

- Page 57 and 58: impolite. However, I soon came to r

- Page 59 and 60: in potential or actual conflict sit

- Page 61 and 62: salient differences. For example, G

- Page 63 and 64: Watts observed that German conversa

- Page 65 and 66: Finally, although Watts argued that

- Page 67 and 68: elatively little overlap, and a gen

- Page 69 and 70: contributions, with the former set

- Page 71 and 72: fully and substantively, what was r

- Page 73 and 74: oriented to unmitigated disagreemen

- Page 75 and 76: 2.3 Communicative Underpinnings The

- Page 77 and 78: service but by more confrontational

- Page 79 and 80: Finally, additional explanatory dim

- Page 81 and 82: specific communicative practices, a

- Page 83 and 84: Brown and Levinson (1987). Indeed,

- Page 85 and 86: Notes to Chapter 2 11 use the term

- Page 87 and 88: This chapter then can be regarded a

- Page 89 and 90: asic irreducible sociological varia

- Page 91 and 92: Fraser (1990) who, in also attempti

- Page 93 and 94: particularly amenable to such a heu

- Page 95 and 96: identify certain underlying dynamic

- Page 97: In fact, these two opposing orienta

- Page 101 and 102: orderly and meaningful conversation

- Page 103 and 104: locally managed and constantly in d

- Page 105 and 106: Poles of Alignment Fig. 3.6 Sociabl

- Page 107 and 108: toward a clearer understanding of w

- Page 109 and 110: Notes to Chapter 3 1 See also Brown

- Page 111 and 112: 4.1 Research Questions In the previ

- Page 113 and 114: eferring to as sociable includes in

- Page 115 and 116: The decision on quantity of data wa

- Page 117 and 118: largely anecdotal evidence from whi

- Page 119 and 120: such as laughter sequences. I also

- Page 121 and 122: Table 4.3 Data: Omissions from Anal

- Page 123 and 124: The obtrusiveness of my recording w

- Page 125 and 126: hand, I did not want to engage in t

- Page 127 and 128: German. However, these episodes asi

- Page 129 and 130: presented here provides a necessary

- Page 131 and 132: two chapters (Chapters 6 and 7). He

- Page 133 and 134: Hand shakes for example were infreq

- Page 135 and 136: eing invariably solidaric in nature

- Page 137 and 138: claimed on the part of the particip

- Page 139 and 140: Table 5.1 Sociable Topics Topic Cat

- Page 141 and 142: in my observations of German sociab

- Page 143 and 144: collective past peppered with indiv

- Page 145 and 146: In the next chapter I want to explo

- Page 147 and 148: CHAPTER 6 ALIGNMENT IN ACTION: NEGA

at any given point in the flow <strong>of</strong> conversation. The central question is <strong>of</strong> course,<br />

how might these observations <strong>of</strong> the underlying dynamics <strong>of</strong> sociable conversation<br />

per se help us in establishing a model its systematic analysis for facework<br />

practices? What can be gleaned from these eclectic observations in terms <strong>of</strong><br />

establishing a suitable framework for the analysis <strong>of</strong> facework in episodes <strong>of</strong><br />

ongoing sociable conversation?<br />

3.3 Sociable Conversation as Facework<br />

I have said that sociable conversation is essentially apolite. For the<br />

facework researcher this causes something <strong>of</strong> a problem, namely, how can one<br />

study facework in a discourse context where communicative behaviour normatively<br />

associated with facework, such as politeness (Brown and Levinson 1987) or<br />

apologies and-accounts (G<strong>of</strong>fman 1967), are normatively and routinely minimised<br />

as part and parcel <strong>of</strong> the achievement <strong>of</strong> sociability. Can, and if so how can, the<br />

observations made about the dynamics <strong>of</strong> sociable and casual conversation aid in<br />

the quest for an appropriate framework for the analysis <strong>of</strong> facework in sociable<br />

episodes?<br />

Earlier I argued for a move from considering positive and negative facework<br />

as properties <strong>of</strong> specific utterance, to treating them more as heuristic or sensitising<br />

devices. In terms <strong>of</strong> ongoing naturally occurring conversation as a discourse type, I<br />

suggested that they could be considered as essentially omnipresent properties <strong>of</strong><br />

the flow <strong>of</strong> conversation. How might though one take positive and negative as<br />

heuristic devices and apply them in the analysis <strong>of</strong> episodes <strong>of</strong> naturally occurring<br />

discourse? What I want to suggest here - and in the light <strong>of</strong> the preceding<br />

discussion certain readers may have already anticipated this, is that, the positive -<br />

negative paradigm advanced by Brown and Levinson can be directly mapped onto<br />

the salient propensities underlying sociable conversation. That is, in claiming<br />

sameness and difference (Eggins and Slade 1997), presenting and sharing<br />

(Watson and Potter 1962), or binding and loosening (Simmel (1949 [1911 ]),<br />

participants in sociable encounters are directly indexing both positive and negative<br />

face needs. Further, these collective practices are operating to ratify and support<br />

an over-arching sociable ethos.<br />

89