Download (23MB) - University of Salford Institutional Repository

Download (23MB) - University of Salford Institutional Repository Download (23MB) - University of Salford Institutional Repository

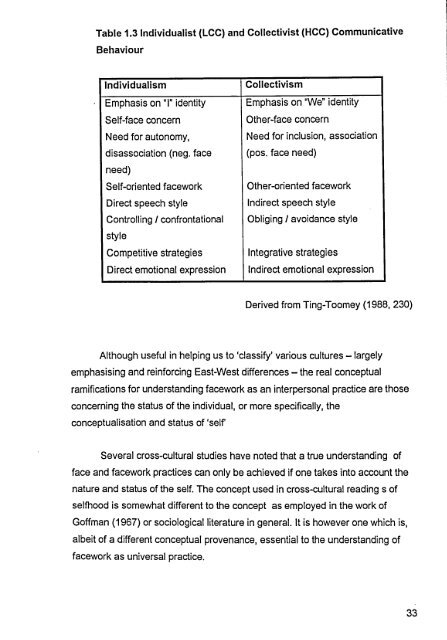

ecognition of and orientation to the individual as an autonomous entity (6 la Brown and Levinson), the latter by taking the individual to be intrinsically bound up to a much greater extent with the wider community. Because of their conceptualisation of the individual and beliefs and values associated with facework, various cultures can be placed along the individualism - collectivism continuum (see fig. 1.5). Fig. 1.4 Examples of Collectivist and Individualist Cultures Collectivist, Japan / China US / Canada 10 Individualist Similarly affecting communicative style across cultures, the high-context - low-context dimension has been posited as more appropriate for understanding cultural variation in situated facework practices. In the former, contextual factors such as the hierarchical relations between interlocutors heavily impact on the nature of the interaction. Conversely, in low-context cultures this is much reduced, with, in effect, more expressive freedom allowed the individual speaker. Again, scholars drawing on this paradigm frequently place Eastern and Western cultures towards opposing ends (see fig. 1.5). Fig. 1.5 Examples of HCC / LCC Cultures HCC LCC -4 lo Korea / Vietnam Germany / Switzerland A culture's positioning along either of these dimensions, not only informs the general attitude an individual may have toward his / her own and others' face concerns, but is manifest in the communicative preferences routinely played out in face to face communication (see table 1.3). 32

Table 1.3 Individualist (LCC) and Collectivist (HCC) Communicative Behaviour Individualism Collectivism Emphasis on "I" identity Emphasis on "We" identity Self-face concern Need for autonomy, Other-face concern Need for inclusion, association disassociation (neg. face (pos. face need) need) Self-oriented facework Other-oriented facework Direct speech style Controlling / confrontational style Competitive strategies Direct emotional expression Indirect speech style Obliging / avoidance style Integrative strategies Indirect emotional expression Derived from Ting-Toomey (1988,230) Although useful in helping us to 'classify' various cultures - largely emphasising and reinforcing East-West differences - the real conceptual ramifications for understanding facework as an interpersonal practice are those concerning the status of the individual, or more specifically, the conceptualisation and status of 'self Several cross-cultural studies have noted that a true understanding of face and facework practices can only be achieved if one takes into account the nature and status of the self. The concept used in cross-cultural reading s of selfhood is somewhat different to the concept as employed in the work of Goffman (1967) or sociological literature in general. It is however one which is, albeit of a different conceptual provenance, essential to the understanding of facework as universal practice. 33

- Page 1 and 2: FACEWORK IN ENGLISH AND GERMAN SOCI

- Page 3 and 4: CHAPTER 4: DOING SOCIA(B)L(E) SCIEN

- Page 5 and 6: Table List of Tables 1.1 Archetypal

- Page 7 and 8: Conversational Excerpts Excerpt Pag

- Page 9 and 10: Acknowledgments Acknowledgements se

- Page 11 and 12: The 'Research Problem' Introduction

- Page 13 and 14: Taking these problematics as a star

- Page 15 and 16: At the time, this proposal seemed e

- Page 17 and 18: the self and its relationship to on

- Page 19 and 20: activity of sociable conversation,

- Page 21 and 22: including the application of the fa

- Page 23 and 24: CHAPTER I FACE AND FACEWORK: CONCEP

- Page 25 and 26: 1.1 Foundational Texts In order to

- Page 27 and 28: communicative action could be seen

- Page 29 and 30: Fig. 1.1 Goffman's Model of Ritual

- Page 31 and 32: distribution of his feelings, and t

- Page 33 and 34: empirically difficult' phenomenon (

- Page 35 and 36: etween self and other). Conversatio

- Page 37 and 38: allowing in effect a speaker to cri

- Page 39 and 40: as an equilibric practice, allowing

- Page 41: universality, particularly in studi

- Page 45 and 46: Morisaki and Gudykunst (1994) emplo

- Page 47 and 48: Mao (1994) addresses this tension b

- Page 49 and 50: Tannen's work (1981 a; 1981 b) perh

- Page 51 and 52: 1.3 Culture, Facework, Equilibrium

- Page 53 and 54: facework operates on an underlying

- Page 55 and 56: CHAPTER 2 ANGLO-SAXON CHALK AND TEU

- Page 57 and 58: impolite. However, I soon came to r

- Page 59 and 60: in potential or actual conflict sit

- Page 61 and 62: salient differences. For example, G

- Page 63 and 64: Watts observed that German conversa

- Page 65 and 66: Finally, although Watts argued that

- Page 67 and 68: elatively little overlap, and a gen

- Page 69 and 70: contributions, with the former set

- Page 71 and 72: fully and substantively, what was r

- Page 73 and 74: oriented to unmitigated disagreemen

- Page 75 and 76: 2.3 Communicative Underpinnings The

- Page 77 and 78: service but by more confrontational

- Page 79 and 80: Finally, additional explanatory dim

- Page 81 and 82: specific communicative practices, a

- Page 83 and 84: Brown and Levinson (1987). Indeed,

- Page 85 and 86: Notes to Chapter 2 11 use the term

- Page 87 and 88: This chapter then can be regarded a

- Page 89 and 90: asic irreducible sociological varia

- Page 91 and 92: Fraser (1990) who, in also attempti

Table 1.3 Individualist (LCC) and Collectivist (HCC) Communicative<br />

Behaviour<br />

Individualism Collectivism<br />

Emphasis on "I" identity Emphasis on "We" identity<br />

Self-face concern<br />

Need for autonomy,<br />

Other-face concern<br />

Need for inclusion, association<br />

disassociation (neg. face (pos. face need)<br />

need)<br />

Self-oriented facework Other-oriented facework<br />

Direct speech style<br />

Controlling / confrontational<br />

style<br />

Competitive strategies<br />

Direct emotional expression<br />

Indirect speech style<br />

Obliging / avoidance style<br />

Integrative strategies<br />

Indirect emotional expression<br />

Derived from Ting-Toomey (1988,230)<br />

Although useful in helping us to 'classify' various cultures - largely<br />

emphasising and reinforcing East-West differences - the real conceptual<br />

ramifications for understanding facework as an interpersonal practice are those<br />

concerning the status <strong>of</strong> the individual, or more specifically, the<br />

conceptualisation and status <strong>of</strong> 'self<br />

Several cross-cultural studies have noted that a true understanding <strong>of</strong><br />

face and facework practices can only be achieved if one takes into account the<br />

nature and status <strong>of</strong> the self. The concept used in cross-cultural reading s <strong>of</strong><br />

selfhood is somewhat different to the concept as employed in the work <strong>of</strong><br />

G<strong>of</strong>fman (1967) or sociological literature in general. It is however one which is,<br />

albeit <strong>of</strong> a different conceptual provenance, essential to the understanding <strong>of</strong><br />

facework as universal practice.<br />

33