Download (23MB) - University of Salford Institutional Repository

Download (23MB) - University of Salford Institutional Repository Download (23MB) - University of Salford Institutional Repository

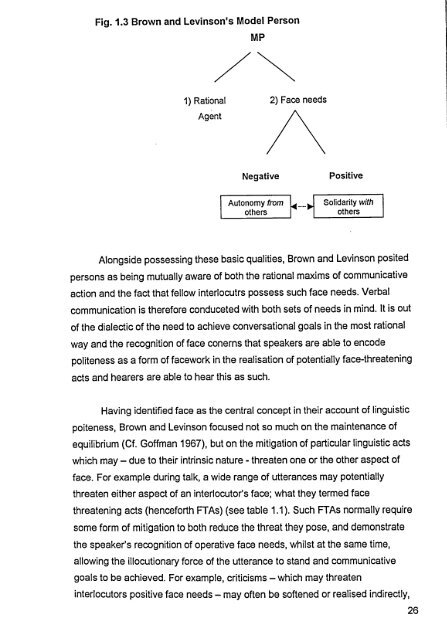

Fig. 1.3 Brown and Levinson's Model Person MP Z**ý'ýý 1) Rational 2) Face needs Agent Negative Positive Autonomy firom Solidarity ; Ersfýý ithý I rr othe others, Alongside possessing these basic qualities, Brown and Levinson posited persons as being mutually aware of both the rational maxims of communicative action and the fact that fellow interlocutrs possess such face needs. Verbal communication is therefore conduceted with both sets of needs in mind. It is out of the dialectic of the need to achieve conversational goals in the most rational way and the recognition of face conerns that speakers are able to encode politeness as a form of facework in the realisation of potentially face-threatening acts and hearers are able to hear this as such. Having identified face as the central concept in their account of linguistic poiteness, Brown and Levinson focused not so much on the maintenance of equilibrium (Cf. Goffman 1967), but on the mitigation of particular linguistic acts which may - due to their intrinsic nature - threaten one or the other aspect of face. For example during talk, a wide range of utterances may potentially threaten either aspect of an interlocutor's face; what they termed face threatening acts (henceforth FTAs) (see table 1.1). Such FTAs normally require some form of mitigation to both reduce the threat they pose, and demonstrate the speaker's recognition of operative face needs, whilst at the same time, allowing the illocutionary force of the utterance to stand and communicative goals to be achieved. For example, criticisms - which may threaten interlocutors positive face needs - may often be softened or realised indirectly, 26

allowing in effect a speaker to criticise politely. Table 1.1 Archetypal Face Threatening Acts and Aspects of Face Threatened Particular face threatened? Aspect of face threatened Negative face Positive face Threaten S Offers Apologies Threaten H Requests Criticisms Brown and Levinson go on to organise a range of such strategies under a hierarchical typology of 'superstrategies for performing FTAs', directly relating to their conceptual isati on of face, and centred around the concepts of positive politeness and negative politeness. I will come back to the specifics of negative and positive politeness in Chapter 3 and subsequent chapters. But, to take for example the act of disagreeing, speakers may encode a disagreement with varying degrees of politeness (see table 1.2). Table 1.2 Politeness and Disagreement Disagreement and politeness: Examples from Brown and Levinson's Superstrategies strategy 1- baldly: "that's a load of rubbish, strategy 2- positive politeness: "come on mate, you must be jokin'", strategy 3- negative politeness: "sorry but I have to disagree there", strategy 4- off record: 'Well, I suppose that's one way of looking at it" strategy 5- don't do FTA 'don't disagree at all'. Essentially then, Brown and Levinson see politeness as the avoidance or mitigation of certain face-threatening acts, according to the aspect of - primarily 27

- Page 1 and 2: FACEWORK IN ENGLISH AND GERMAN SOCI

- Page 3 and 4: CHAPTER 4: DOING SOCIA(B)L(E) SCIEN

- Page 5 and 6: Table List of Tables 1.1 Archetypal

- Page 7 and 8: Conversational Excerpts Excerpt Pag

- Page 9 and 10: Acknowledgments Acknowledgements se

- Page 11 and 12: The 'Research Problem' Introduction

- Page 13 and 14: Taking these problematics as a star

- Page 15 and 16: At the time, this proposal seemed e

- Page 17 and 18: the self and its relationship to on

- Page 19 and 20: activity of sociable conversation,

- Page 21 and 22: including the application of the fa

- Page 23 and 24: CHAPTER I FACE AND FACEWORK: CONCEP

- Page 25 and 26: 1.1 Foundational Texts In order to

- Page 27 and 28: communicative action could be seen

- Page 29 and 30: Fig. 1.1 Goffman's Model of Ritual

- Page 31 and 32: distribution of his feelings, and t

- Page 33 and 34: empirically difficult' phenomenon (

- Page 35: etween self and other). Conversatio

- Page 39 and 40: as an equilibric practice, allowing

- Page 41 and 42: universality, particularly in studi

- Page 43 and 44: Table 1.3 Individualist (LCC) and C

- Page 45 and 46: Morisaki and Gudykunst (1994) emplo

- Page 47 and 48: Mao (1994) addresses this tension b

- Page 49 and 50: Tannen's work (1981 a; 1981 b) perh

- Page 51 and 52: 1.3 Culture, Facework, Equilibrium

- Page 53 and 54: facework operates on an underlying

- Page 55 and 56: CHAPTER 2 ANGLO-SAXON CHALK AND TEU

- Page 57 and 58: impolite. However, I soon came to r

- Page 59 and 60: in potential or actual conflict sit

- Page 61 and 62: salient differences. For example, G

- Page 63 and 64: Watts observed that German conversa

- Page 65 and 66: Finally, although Watts argued that

- Page 67 and 68: elatively little overlap, and a gen

- Page 69 and 70: contributions, with the former set

- Page 71 and 72: fully and substantively, what was r

- Page 73 and 74: oriented to unmitigated disagreemen

- Page 75 and 76: 2.3 Communicative Underpinnings The

- Page 77 and 78: service but by more confrontational

- Page 79 and 80: Finally, additional explanatory dim

- Page 81 and 82: specific communicative practices, a

- Page 83 and 84: Brown and Levinson (1987). Indeed,

- Page 85 and 86: Notes to Chapter 2 11 use the term

Fig. 1.3 Brown and Levinson's Model Person<br />

MP<br />

Z**ý'ýý<br />

1) Rational 2) Face needs<br />

Agent<br />

Negative Positive<br />

Autonomy firom Solidarity ; Ersfýý<br />

ithý<br />

I rr<br />

othe<br />

others,<br />

Alongside possessing these basic qualities, Brown and Levinson posited<br />

persons as being mutually aware <strong>of</strong> both the rational maxims <strong>of</strong> communicative<br />

action and the fact that fellow interlocutrs possess such face needs. Verbal<br />

communication is therefore conduceted with both sets <strong>of</strong> needs in mind. It is out<br />

<strong>of</strong> the dialectic <strong>of</strong> the need to achieve conversational goals in the most rational<br />

way and the recognition <strong>of</strong> face conerns that speakers are able to encode<br />

politeness as a form <strong>of</strong> facework in the realisation <strong>of</strong> potentially face-threatening<br />

acts and hearers are able to hear this as such.<br />

Having identified face as the central concept in their account <strong>of</strong> linguistic<br />

poiteness, Brown and Levinson focused not so much on the maintenance <strong>of</strong><br />

equilibrium (Cf. G<strong>of</strong>fman 1967), but on the mitigation <strong>of</strong> particular linguistic acts<br />

which may - due to their intrinsic nature - threaten one or the other aspect <strong>of</strong><br />

face. For example during talk, a wide range <strong>of</strong> utterances may potentially<br />

threaten either aspect <strong>of</strong> an interlocutor's face; what they termed face<br />

threatening acts (henceforth FTAs) (see table 1.1). Such FTAs normally require<br />

some form <strong>of</strong> mitigation to both reduce the threat they pose, and demonstrate<br />

the speaker's recognition <strong>of</strong> operative face needs, whilst at the same time,<br />

allowing the illocutionary force <strong>of</strong> the utterance to stand and communicative<br />

goals to be achieved. For example, criticisms - which may threaten<br />

interlocutors positive face needs - may <strong>of</strong>ten be s<strong>of</strong>tened or realised indirectly,<br />

26