Download (23MB) - University of Salford Institutional Repository

Download (23MB) - University of Salford Institutional Repository Download (23MB) - University of Salford Institutional Repository

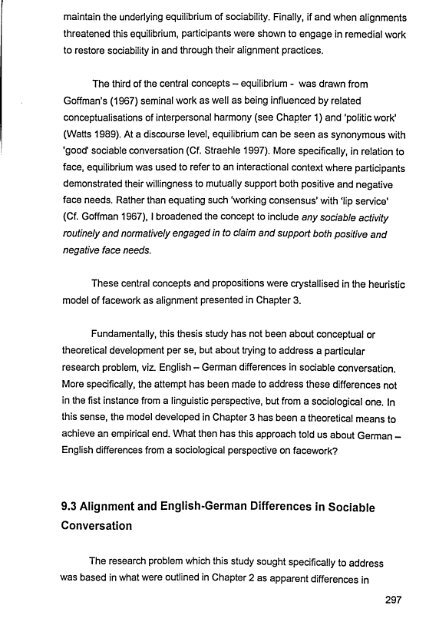

Fig. 9.1 The Symbolic Propensities of the Conversational Self - Contraction of Expansion of Contraction Self Self of Self Mobilisation and Alignment of Selves as Conversational Players and Images ONGOING CONVERSATIONAL FLOW --jo. The Self as Conversational Construal Face Needs I have treated the second key term of alignment in quite general terms to refer to the way selves are mobilised vis-ý-vis other selves in talk. Participants in sociable episodes have been conceived of as being both alignable and align- dependent entities in their sociable capacities. In sociable episodes, particular selves were shown to be mobilised, commonly typical ones, recognisable by co- participants as sociable. In order to ratify and support these selves, appropriate recipient selves were shown to be mobilised and, appropriately aligned. I demonstrated in Chapter 6 that the facework as alignment approach allows for a range of conversational possibilities centred around the ratification and n on-ratifi cation of sociable selves. It was argued that - and in line with Goffman's (1967) comments on the fundamental condition of ritual equilibrium under normal circumstances, selves are aligned in a way that encouraged ratification and support. This preference for ratification was shown to apply equally to both negative and positive alignment. On occasions when selves were not ratified, participants were shown to normatively re-align so as to 296

maintain the underlying equilibrium of sociability. Finally, if and when alignments threatened this equilibrium, participants were shown to engage in remedial work to restore sociability in and through their alignment practices. The third of the central concepts - equilibrium - was drawn from Goffman's (1967) seminal work as well as being influenced by related conceptualisations of interpersonal harmony (see Chapter 1) and 'politic work' (Wafts 1989). At a discourse level, equilibrium can be seen as synonymous with 'good' sociable conversation (Cf. Straehle 1997). More specifically, in relation to face, equilibrium was used to refer to an interactional context where participants demonstrated their willingness to mutually support both positive and negative face needs. Rather than equating such 'working consensus' with 'lip service' (Cf. Goffman 1967), 1 broadened the concept to include any sociable activity routinely and normatively engaged in to claim and support both positive and negative face needs. These central concepts and propositions were crystallised in the heuristic model of facework as alignment presented in Chapter 3. Fundamentally, this thesis study has not been about conceptual or theoretical development per se, but about trying to address a particular research problem, viz. English - German differences in sociable conversation. More specifically, the attempt has been made to address these differences not in the fist instance from a linguistic perspective, but from a sociological one. In this sense, the model developed in Chapter 3 has been a theoretical means to achieve an empirical end. What then has this approach told us about German - English differences from a sociological perspective on facework? 9.3 Alignment and English-German Differences in Sociable Conversation The research problem which this study sought specifically to address was based in what were outlined in Chapter 2 as apparent differences in 297

- Page 255 and 256: as re-invoking selves. The category

- Page 257 and 258: An interesting phenomenon which is

- Page 259 and 260: An additional consequence of alignm

- Page 261 and 262: Conversely, in considering the next

- Page 263 and 264: 100 KP: I mean you see two or three

- Page 265 and 266: however, such narrating selves are

- Page 267 and 268: Running alongside these narrative s

- Page 269 and 270: capabilities of KP&EP and in this w

- Page 271 and 272: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

- Page 273 and 274: 6 (0.5) 7 EP: America is booming at

- Page 275 and 276: own unemployment levels -a concern

- Page 277 and 278: In terms of the selves mobilised, t

- Page 279 and 280: in 'Cookie's Party'- again, a secon

- Page 281 and 282: 35 GB: kann man nie als [endgültig

- Page 283 and 284: is HB: =Yeah not at all but e:: rm=

- Page 285 and 286: episode takes place. Rather, the ta

- Page 287 and 288: The excerpt begins as HB is proffer

- Page 289 and 290: What this talk demonstrates is that

- Page 291 and 292: N work or'Arbeit' being an extremel

- Page 293 and 294: demeaned and knowledgeable selves (

- Page 295 and 296: preceding comments regarding sociab

- Page 297 and 298: CHAPTER 9 CONCLUSION: THE TO AND FR

- Page 299 and 300: identified in conversational behavi

- Page 301 and 302: handled sociable topics, in terms o

- Page 303 and 304: to bring themselves and their inter

- Page 305: sociable conversation. This sociabl

- Page 309 and 310: allowed for by the facework as alig

- Page 311 and 312: somebody who is overly-friendly, ge

- Page 313 and 314: Fig 9.2 A Maxim of Conversational P

- Page 315 and 316: Notes to Chapter 9 1 When we are ta

- Page 317 and 318: German Participants Name Age Occupa

- Page 319 and 320: German Gatherings Gathering Date Se

- Page 321 and 322: Brown, G., and Yule, G. (1983) Disc

- Page 323 and 324: Ervin-Tripp, S., Nakamura, K, and G

- Page 325 and 326: Hellweg, S A., Samovar, L A., and S

- Page 327 and 328: Hu, H C. (1944) The Chinese concept

- Page 329 and 330: - (1979) 'Stylistic Strategies with

- Page 331 and 332: - (1994) 'Facework in Communication

- Page 333 and 334: Snell-Hornby, M.. (1984) 'The Lingu

- Page 335 and 336: Trubisky, P., Ting-Toomey, S., and

maintain the underlying equilibrium <strong>of</strong> sociability. Finally, if and when alignments<br />

threatened this equilibrium, participants were shown to engage in remedial work<br />

to restore sociability in and through their alignment practices.<br />

The third <strong>of</strong> the central concepts - equilibrium - was drawn from<br />

G<strong>of</strong>fman's (1967) seminal work as well as being influenced by related<br />

conceptualisations <strong>of</strong> interpersonal harmony (see Chapter 1) and 'politic work'<br />

(Wafts 1989). At a discourse level, equilibrium can be seen as synonymous with<br />

'good' sociable conversation (Cf. Straehle 1997). More specifically, in relation to<br />

face, equilibrium was used to refer to an interactional context where participants<br />

demonstrated their willingness to mutually support both positive and negative<br />

face needs. Rather than equating such 'working consensus' with 'lip service'<br />

(Cf. G<strong>of</strong>fman 1967), 1 broadened the concept to include any sociable activity<br />

routinely and normatively engaged in to claim and support both positive and<br />

negative face needs.<br />

These central concepts and propositions were crystallised in the heuristic<br />

model <strong>of</strong> facework as alignment presented in Chapter 3.<br />

Fundamentally, this thesis study has not been about conceptual or<br />

theoretical development per se, but about trying to address a particular<br />

research problem, viz. English - German differences in sociable conversation.<br />

More specifically, the attempt has been made to address these differences not<br />

in the fist instance from a linguistic perspective, but from a sociological one. In<br />

this sense, the model developed in Chapter 3 has been a theoretical means to<br />

achieve an empirical end. What then has this approach told us about German -<br />

English differences from a sociological perspective on facework?<br />

9.3 Alignment and English-German Differences in Sociable<br />

Conversation<br />

The research problem which this study sought specifically to address<br />

was based in what were outlined in Chapter 2 as apparent differences in<br />

297