Download (23MB) - University of Salford Institutional Repository

Download (23MB) - University of Salford Institutional Repository Download (23MB) - University of Salford Institutional Repository

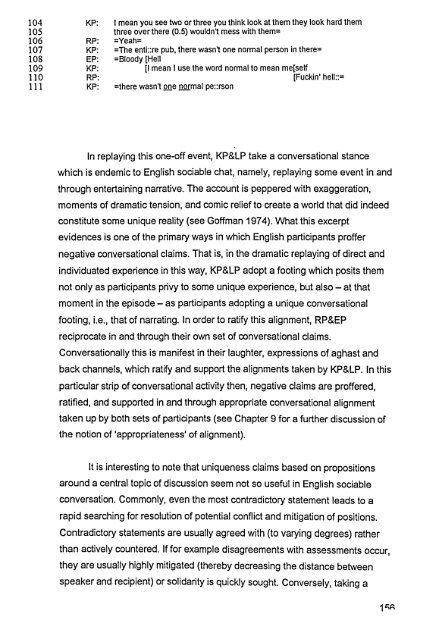

104 KP: I mean you see two or three you think look at them they look hard them 105 three over there (0.5) wouldn't mess with them= 106 RP: =Yeah= 107 KP: =The enti:: re pub, there wasn't one normal person in there= 108 EP: =Bloody [Hell 109 KP: 11 mean I use the word normal to mean me[self 110 RP: [Fuckin'hell:: = ill KP: =there wasn't one normal pe:: rson In replaying this one-off event, KPUP take a conversational stance which is endemic to English sociable chat, namely, replaying some event in and through entertaining narrative. The account is peppered with exaggeration, moments of dramatic tension, and comic relief to create a world that did indeed constitute some unique reality (see Goffman 1974). What this excerpt evidences is one of the primary ways in which English participants proffer negative conversational claims. That is, in the dramatic replaying of direct and individuated experience in this way, KP&LP adopt a footing which posits them not only as participants privy to some unique experience, but also - at that moment in the episode - as participants adopting a unique conversational footing, i. e., that of narrating. In order to ratify this alignment, RP&EP reciprocate in and through their own set of conversational claims. Conversationally this is manifest in their laughter, expressions of aghast and back channels, which ratify and support the alignments taken by KP&LP. In this particular strip of conversational activity then, negative claims are proffered, ratified, and supported in and through appropriate conversational alignment taken up by both sets of participants (see Chapter 9 for a further discussion of the notion of 'appropriateness' of alignment). It is interesting to note that uniqueness claims based on propositions around a central topic of discussion seem not so useful in English sociable conversation. Commonly, even the most contradictory statement leads to a rapid searching for resolution of potential conflict and mitigation of positions. Contradictory statements are usually agreed with (to varying degrees) rather than actively countered. If for example disagreements with assessments occur, they are usually highly mitigated (thereby decreasing the distance between speaker and recipient) or solidarity is quickly sought. Conversely, taking a 1 '; r,

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 standpoint which is somehow differentiated from those proffered by others co- present seems to be a prime way for German participants in sociable episodes to make and have supported negative conversational claims. When similar minded Germans come together (or more accurately when similar 'conversational selves' are mobilised - see Chapters 7 and 8), the result is what has been termed 'Wettkampf (Kotthoff 1991). At such moments, Germans interactants 'agree to disagree' as it were. Conflictual standpoints of 'real' argumentation are 'keyed' (Goffman 1974) in the playing out of a sociable pursuit. Such Wettkampf encounters were not as endemic in my own German conversations as the literature suggested, but they did provide a primary and salient routinised way in which negative alignment was normatively conducted in the same way that narrative functions in English. The following example of focused topic talk - about something as innocuous as the length of queues in Aldi - demonstrates nicely this use of conversational topic as a resource for individuated claims and negative alignment Excerpt 6.6 'Schlange bei Aldi' The immediately preceding talk has been about similar experiences of having to queue in mutually known supermarkets HB: Bei Ald! habe ich mich oft drüber geärgert ich >sage mir was soll das< EP: =hm:: = HB: =Ja bevor (. ) die Schlange nicht zehn Meter lang ist (0.5) denn=denn kommt keine zweite Person an die Kasse=und wenn wieder auf fünf=drei=vier-- fünf Meter abgebaut ist (. ) dann geht die ex (. ) zweite schon wieder weg= KN: Ja >aber wenn [die DA WAS SOLL DEnn die machen< wenn die nur mit HB: [Ich sach die RAUBT einem doch nur drei [Personen da stehen HB: [DIE RAUbt einem doch nur die Zeit (. ) das ist [doch KN: [JA::: = HB: =Das fördert doch nicht den ihren Umsatz und [und KN: [Ja:: HB: E: r-denn ich sage ja nicht=>na gut wenn ich mehr Zeit habe< dann kaufe ich mehr das ist doch Quatsch:: ne (. ) >nur daß die Leute mehr stehen und verä[rgert sindAber die haben zu wenig Leute< [das ist HB: [Und irgendwann sind sie=ja ja: ist mir kla: rja:: [: GB: [Ganz knapp [kalkuliert= 1 r%7

- Page 115 and 116: The decision on quantity of data wa

- Page 117 and 118: largely anecdotal evidence from whi

- Page 119 and 120: such as laughter sequences. I also

- Page 121 and 122: Table 4.3 Data: Omissions from Anal

- Page 123 and 124: The obtrusiveness of my recording w

- Page 125 and 126: hand, I did not want to engage in t

- Page 127 and 128: German. However, these episodes asi

- Page 129 and 130: presented here provides a necessary

- Page 131 and 132: two chapters (Chapters 6 and 7). He

- Page 133 and 134: Hand shakes for example were infreq

- Page 135 and 136: eing invariably solidaric in nature

- Page 137 and 138: claimed on the part of the particip

- Page 139 and 140: Table 5.1 Sociable Topics Topic Cat

- Page 141 and 142: in my observations of German sociab

- Page 143 and 144: collective past peppered with indiv

- Page 145 and 146: In the next chapter I want to explo

- Page 147 and 148: CHAPTER 6 ALIGNMENT IN ACTION: NEGA

- Page 149 and 150: shall not be carried forward into t

- Page 151 and 152: These various symbols are intended

- Page 153 and 154: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

- Page 155 and 156: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Rather than

- Page 157 and 158: 19 EP: ' [Although I mean that [now

- Page 159 and 160: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

- Page 161 and 162: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

- Page 163 and 164: detrimental effects foreigners are

- Page 165: 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52

- Page 169 and 170: 28 HB: but at the end of the day >1

- Page 171 and 172: approach, I hope to further illumin

- Page 173 and 174: 37 KJ: I never had any day to day (

- Page 175 and 176: 2 bevor (. ) die Schlange nicht zeh

- Page 177 and 178: ot non-ratifi cation and non-suppor

- Page 179 and 180: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

- Page 181 and 182: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

- Page 183 and 184: What happens in this particular exc

- Page 185 and 186: To reiterate, positive threshold br

- Page 187 and 188: 41 LIP: [IN FACT THERE WAs quite a

- Page 189 and 190: What happens here is that KIP proff

- Page 191 and 192: 17 KH: the road (1) >and if he want

- Page 193 and 194: 1 2 3 4 5 6 which a new set of indi

- Page 195 and 196: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

- Page 197 and 198: and English differences in conversa

- Page 199 and 200: Notes to Chapter 6 1 The only insta

- Page 201 and 202: study is a sociological one, and it

- Page 203 and 204: performer, a player, an image, a fi

- Page 205 and 206: English cultures respectively. In a

- Page 207 and 208: I will shortly illustrate how each

- Page 209 and 210: 18 KJ: [(Graphic drawin)= 19 LM: =O

- Page 211 and 212: The in-the-know self is a second sy

- Page 213 and 214: documentaries to having witnessed r

- Page 215 and 216: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 is

104 KP: I mean you see two or three you think look at them they look hard them<br />

105 three over there (0.5) wouldn't mess with them=<br />

106 RP: =Yeah=<br />

107 KP: =The enti:: re pub, there wasn't one normal person in there=<br />

108 EP: =Bloody [Hell<br />

109 KP: 11 mean I use the word normal to mean me[self<br />

110 RP: [Fuckin'hell:: =<br />

ill KP: =there wasn't one normal pe:: rson<br />

In replaying this one-<strong>of</strong>f event, KPUP take a conversational stance<br />

which is endemic to English sociable chat, namely, replaying some event in and<br />

through entertaining narrative. The account is peppered with exaggeration,<br />

moments <strong>of</strong> dramatic tension, and comic relief to create a world that did indeed<br />

constitute some unique reality (see G<strong>of</strong>fman 1974). What this excerpt<br />

evidences is one <strong>of</strong> the primary ways in which English participants pr<strong>of</strong>fer<br />

negative conversational claims. That is, in the dramatic replaying <strong>of</strong> direct and<br />

individuated experience in this way, KP&LP adopt a footing which posits them<br />

not only as participants privy to some unique experience, but also - at that<br />

moment in the episode - as participants adopting a unique conversational<br />

footing, i. e., that <strong>of</strong> narrating. In order to ratify this alignment, RP&EP<br />

reciprocate in and through their own set <strong>of</strong> conversational claims.<br />

Conversationally this is manifest in their laughter, expressions <strong>of</strong> aghast and<br />

back channels, which ratify and support the alignments taken by KP&LP. In this<br />

particular strip <strong>of</strong> conversational activity then, negative claims are pr<strong>of</strong>fered,<br />

ratified, and supported in and through appropriate conversational alignment<br />

taken up by both sets <strong>of</strong> participants (see Chapter 9 for a further discussion <strong>of</strong><br />

the notion <strong>of</strong> 'appropriateness' <strong>of</strong> alignment).<br />

It is interesting to note that uniqueness claims based on propositions<br />

around a central topic <strong>of</strong> discussion seem not so useful in English sociable<br />

conversation. Commonly, even the most contradictory statement leads to a<br />

rapid searching for resolution <strong>of</strong> potential conflict and mitigation <strong>of</strong> positions.<br />

Contradictory statements are usually agreed with (to varying degrees) rather<br />

than actively countered. If for example disagreements with assessments occur,<br />

they are usually highly mitigated (thereby decreasing the distance between<br />

speaker and recipient) or solidarity is quickly sought. Conversely, taking a<br />

1 '; r,