WT_2004_05: ROLEX: THE STATUS SYMBOL

WT_2004_05: ROLEX: THE STATUS SYMBOL

WT_2004_05: ROLEX: THE STATUS SYMBOL

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>ROLEX</strong><br />

<strong>THE</strong> <strong>STATUS</strong><br />

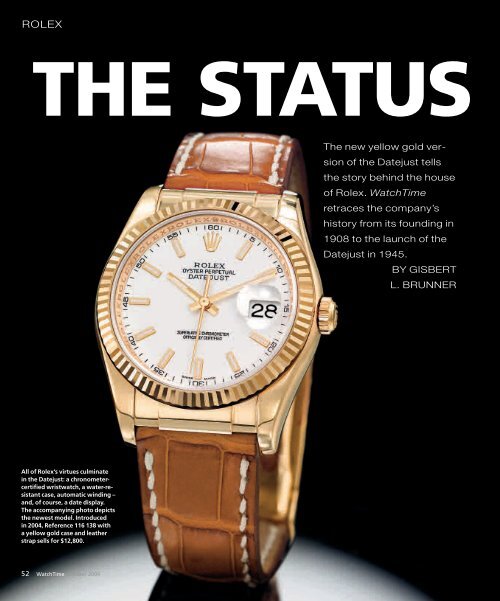

All of Rolex’s virtues culminate<br />

in the Datejust: a chronometercertified<br />

wristwatch, a water-resistant<br />

case, automatic winding –<br />

and, of course, a date display.<br />

The accompanying photo depicts<br />

the newest model. Introduced<br />

in <strong>2004</strong>, Reference 116 138 with<br />

a yellow gold case and leather<br />

strap sells for $12,800.<br />

52 WatchTime October <strong>2004</strong><br />

The new yellow gold version<br />

of the Datejust tells<br />

the story behind the house<br />

of Rolex. WatchTime<br />

retraces the company’s<br />

history from its founding in<br />

1908 to the launch of the<br />

Datejust in 1945.<br />

BY GISBERT<br />

L. BRUNNER

<strong>SYMBOL</strong><br />

The history of Rolex, like that of so<br />

many important global brands, began<br />

with an impressive entrepreneurial<br />

personality. Hans Wilsdorf left his native Germany<br />

at age 19 and went to Switzerland,<br />

where he got his first taste of the watch business.<br />

He moved on to London a few years later,<br />

where he found a business partner and<br />

started his own business. The company of<br />

Wilsdorf & Davis Ltd. conducted business at<br />

83 Hatton Gardens, where Wilsdorf laid the<br />

foundation for what would ultimately become<br />

a global watch empire.<br />

Wilsdorf was a skilful businessman with<br />

ambition and foresight. Soon after the turn of<br />

the 20th century, when most men wore pocket-watches<br />

and many people ridiculed the first<br />

timepieces for the wrist, he sensed that the future<br />

would in fact belong to the wristwatch.<br />

His business idea was a good one, but a critical<br />

ingredient was lacking. Wilsdorf hadn’t yet<br />

found a precise movement that could be encased<br />

inside a fashionable and adequately water-resistant<br />

case.<br />

This was the situation facing him when he<br />

moved his business to 44 Holborn Viaduct.<br />

The market square in Kulmbach, Germany. Wilsdorf’s<br />

grandfather’s shop can be seen in the center of the photo.<br />

Wilsdorf’s contacts with the Swiss watchmaking<br />

industry stood him in good stead now. He<br />

traveled to Biel and visited Aegler SA, a watch<br />

business that had developed an 11-ligne movement<br />

with a lever escapement and had already<br />

successfully encased that caliber inside its own<br />

wristwatches. Wilsdorf offered to distribute Aegler’s<br />

wristwatches in Great Britain, and the<br />

Swiss firm was amenable to the idea. By the end<br />

of his visit, the partners agreed on a first deal<br />

worth several hundred thousand Swiss francs.<br />

This was a daring step for Wilsdorf because the<br />

value of the deal was five times larger than the<br />

total operating capital of Wilsdorf & Davis Ltd.<br />

Fortunately, the reward for his courage was<br />

soon forthcoming. In 1913, Wilsdorf & Davis<br />

was granted exclusive rights to distribute Aegler<br />

wristwatches in Great Britain and throughout<br />

the British Empire.<br />

This trailblazing success didn’t materialize<br />

out of thin air. To simplify business dealings be-<br />

tween London and Switzerland, Wilsdorf had<br />

established an office in La Chaux-de-Fonds in<br />

1907. In 1912, when the collaboration with<br />

Aegler was already proceeding smoothly, Wilsdorf<br />

moved the office to Biel, where a managing<br />

agent ran things.<br />

Wilsdorf was too ambitious to accept the<br />

fact that the big English specialty shops like<br />

The Goldsmiths Company or Asprey insisted<br />

that their own name appear on the dials (and<br />

HANS WILSDORF WAS TOO AMBITIOUS TO LANGUISH<br />

IN ANONYMITY. HE WANTED TO MAKE A<br />

WATCH WITH HIS OWN BRAND NAME ON <strong>THE</strong> DIAL.<br />

sometimes even on the movements), forcing<br />

suppliers to languish in anonymity. With characteristic<br />

tenacity, he set out to put an end to<br />

this glory-hogging tradition. To accomplish his<br />

goal, however, he needed a brand name of his<br />

own and highly recognizable products.<br />

The beginning came in 1908 with the coining<br />

of the word “Rolex.” According to an unconfirmed<br />

legend, the neologism was born as<br />

an abbreviation of the French phrase “horlogerie<br />

exquise,” which means “exquisite ho-<br />

A view of Geneva and Quai Wilson, where<br />

Hans Wilsdorf lived during the 1950s.<br />

October <strong>2004</strong> WatchTime 53

<strong>ROLEX</strong><br />

rology.” Wilsdorf opted for the word “Rolex”<br />

because it could readily be pronounced in<br />

many different languages. Also, the two short,<br />

simple syllables required so little space on a<br />

watch’s dial that there was still plenty of room<br />

left to eternalize a jeweler’s name along with<br />

it. Wilsdorf’s next strategy was to make the Rolex<br />

name synonymous with quality and exclusivity.<br />

He asked his customers for permission to<br />

print “Rolex” on only a few of the watches<br />

that he supplied. After these pioneers had sold<br />

well, he gradually began increasing the number<br />

of “Rolex” watches in each package of six<br />

timepieces. Starting in 1925, he launched a series<br />

of uncommonly creative advertising campaigns<br />

in England. A further contribution to<br />

this successful strategy was made by the British<br />

Commonwealth and its world-traveling citizens,<br />

whose precise Rolex watches attracted<br />

admiring attention wherever they went. Nev-<br />

Rolex’s founder: Hans Wilsdorf<br />

The man who would go down in history as the<br />

founder of the world’s best-known brand of luxury<br />

watches was born in Kulmbach, Germany on<br />

March 22, 1881. Anna and Ferdinand Wilsdorf<br />

named their second child Hans Wilhelm. The talented<br />

boy enjoyed a sheltered childhood for the<br />

first twelve years of his life. But then his parents<br />

died unexpectedly, leaving uncles on his mother’s<br />

side of the family to care for the three orphaned<br />

Wilsdorf children. Hans was sent to a boarding<br />

school in Coburg, from which he graduated at the<br />

unusually young age of 17. He then went to business<br />

school in Bayreuth before turning his back on<br />

Germany at the turn of the 20th century. Wilsdorf’s<br />

late mother was a descendant of the wellknown<br />

Maisel brewing dynasty, so she had hoped<br />

her son would join the family business, but Hans<br />

had other plans. After a brief training with a pearl<br />

dealer in Geneva, he found a job that suited him at<br />

Cuna Korten in La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1900. This<br />

firm, which had its headquarters on posh Boulevard<br />

Léopold Robert, exported watches of all varieties.<br />

For a monthly salary of 80 francs, the multilingual<br />

newcomer took care of English correspondence<br />

and general office tasks. Among his daily<br />

chores was winding and monitoring the rates of<br />

several hundred watches. Korten, which generated<br />

an annual turnover in excess of one million<br />

francs, sparked Wilsdorf’s lifelong fascination with<br />

ticking timepieces. Korten purchased the greater<br />

portion of its merchandise from producers in Germany,<br />

France, and Switzerland. The ambitious<br />

young office assistant soon knew that his true calling<br />

was to go into business on his own. Wilsdorf<br />

54 WatchTime October <strong>2004</strong><br />

ertheless, 19 years would pass before Wilsdorf<br />

was able to deliver nothing but watches bearing<br />

his own insignia on their dials, movements,<br />

and cases. The final breakthrough came with<br />

the launch of the world’s first truly water-resistant<br />

wristwatch. Whether they liked it or not,<br />

dealers who wanted to sell this futuristic product<br />

now had no other choice but to accept the<br />

presence of the name “Rolex.” Wilsdorf had<br />

not only developed a genuinely practical wristwatch<br />

for daily use; he had also given the<br />

product a distinctive brand identity.<br />

More or less simultaneously with the start<br />

of the First World War, Wilsdorf and his partner<br />

in Biel agreed to change the name of the company.<br />

The firm that had formerly been known<br />

as “Les Fils de Jean Aelger – Fabrique Rebberg”<br />

was renamed “Rolex Watch Co., Aegler<br />

S.A., Manufacture d’Horlogerie, Usine du Rebberg.”<br />

Approximately 200 employees were<br />

commissioned three excellent<br />

watchmakers to<br />

each craft a golden chronometer-qualitypocketwatch.<br />

Neuchâtel Observatory<br />

duly awarded an<br />

official rate certificate to<br />

each watch. It didn’t<br />

take Wilsdorf long to sell all three pocket-watches<br />

for a tidy profit. Impressed, Wilsdorf’s bosses entrusted<br />

new tasks and greater responsibilities to<br />

their brilliant young employee, but the narrow horizons<br />

of the company were too confining for Wilsdorf.<br />

After a compulsory army stint in Germany, he<br />

again packed his bags and went to London. He arrived<br />

there in 1903 and founded his own business<br />

two years later.<br />

His beginning was hardly auspicious: Thieves had<br />

stolen his inheritance, which totaled 33,000 German<br />

gold marks, during a ship voyage, so he was<br />

obliged to borrow starting capital from his siblings<br />

and from a much older business partner named Alfred<br />

James Davis. Wilsdorf soon settled in and acquired<br />

British citizenship, a decision spurred on by a<br />

legal battle with the city of Geneva about the confiscation<br />

of a plot of land on the shore of Lac Léman.<br />

After the death of his first wife, May Florence,<br />

Wilsdorf married a native of Appenzell in 1950.<br />

During the winter months, the couple resided in<br />

their large, comfortable home at no. 39, Quai Wilson.<br />

The best ideas typically occurred to Wilsdorf<br />

during his morning ablutions, so the extremely well<br />

endowed gourmand and wine connoisseur usually<br />

spent up to two hours in the bath each morning.<br />

The cover of a brochure<br />

from the World War One era.<br />

occupied with the manufacture of Rolex<br />

watches. The enterprise conducted its business<br />

on the other side of the English Channel<br />

under the name “Wilsdorf & Davis, Rolex<br />

Watch Company.” This name was changed to<br />

This was where he conceived the famous magnifying<br />

(Cyclops) lens above the Oyster’s date display,<br />

which was originally intended to help his<br />

nearsighted wife read the date on her wristwatch.<br />

After breakfast, his trusty chauffeur Rüttimann<br />

would drive him to work in his Mercedes. Rolex’s<br />

boss had first put his trust in the German car<br />

brand around 1935. Rolls Royce repeatedly tried<br />

to convince Wilsdorf of the merits of their noble<br />

British brand, but had no luck in changing his<br />

mind.<br />

Wilsdorf’s employees appreciated the human<br />

side of their boss. At Christmas and before the<br />

beginning of the watchmakers’ annual vacation<br />

season, it was his habit to stroll through each department<br />

and shake each employee’s hand and<br />

personally thank them for their hard work. On<br />

Saturday mornings, Wilsdorf would occasionally<br />

invite a few friends to share a glass of port with<br />

him and listen to anecdotes about his far-flung<br />

journeys. In his later years, the firm’s founder was<br />

burdened by a limp but otherwise healthy. At his<br />

75th birthday celebration in 1956, one of the<br />

highlights of the evening was the presentation to<br />

Wilsdorf of a genuine world premiere: the Stick-<br />

O-Matic, a walking stick with a built-in self-winding<br />

watch.<br />

Twenty-one years after his death, Wilsdorf’s<br />

adopted hometown of Geneva honored him by<br />

naming a street after him. His native town of<br />

Kulmbach, Germany keeps his memory alive at<br />

Hans Wilsdorf Vocational School. His name, however,<br />

cannot rival that of “Rolex”, the brand that<br />

he invented and piloted to global renown.

Some early Rolex models. The one at the far left dates from 1915.<br />

“The Rolex Watch Company Ltd.” in November<br />

1915. More than 60 employees took care<br />

of worldwide sales here. They keenly felt the<br />

consequences of the war in 1919, when more<br />

or less overnight, the British government decided<br />

to impose a 33.3% duty fee on imports.<br />

Wilsdorf wasn’t very happy with Davis, so he<br />

bought out his partner’s share in the business.<br />

Wilsdorf and his wife moved to Geneva, and<br />

from this epicenter of luxury watchmaking,<br />

Wilsdorf planned to deliver his watches to a<br />

rapidly growing global market. The name<br />

“Montres Rolex S.A.” was registered on January<br />

17, 1920. The company’s sole proprietor<br />

and director explained the reasons for his decision<br />

to settle in the Rhône metropolis: “We settled<br />

in Geneva because we want to let our factory<br />

in Biel devote itself exclusively to the manufacture<br />

of watch movements, while we in<br />

Geneva concentrate on creating case models<br />

that suit the cultivated tastes of cosmopolitan<br />

Geneva. Components for Rolex movements<br />

will be made in Biel, but the calibers themselves<br />

will be assembled in Geneva, where they’ll be<br />

56 WatchTime October <strong>2004</strong><br />

The first chronometer<br />

tested in Kew<br />

subjected to the most meticulous testing.” Rolex’s<br />

familiar crown-shaped trademark was first<br />

officially registered in 1925. The five points on<br />

the crown represent the letters in the brand’s<br />

name and simultaneously symbolize the five<br />

fingers on a human hand.<br />

Business flourished steadily until September<br />

21, 1931, when the British pound was drastically<br />

devalued in the wake of the worldwide<br />

economic crisis. This devaluation had a dire effect<br />

on Rolex. Prices charged to customers<br />

throughout the Empire, which was still the<br />

company’s most important market, had to be<br />

adjusted upwards. Exports declined by more<br />

than 60%. If Rolex were to survive, the brand<br />

would have to acquire clientele not living under<br />

the Union Jack. Wilsdorf established subsidiaries<br />

in Paris, Buenos Aires, and Milan. He<br />

also commenced business activities in the Far<br />

East. The expansion paid off, as production of<br />

Oyster models gradually increased from 2,500<br />

to roughly 30,000 watches per year.<br />

Fate dealt Wilsdorf a harsh blow in 1944,<br />

just one year prior to the planned anniversary<br />

celebration, when his wife May Florence died<br />

unexpectedly. The couple had always spent<br />

the winters at Hotel des Bergues in Geneva,<br />

where they resided in a suite of rooms that was<br />

furnished with their own furniture and their<br />

own piano. In accord with his wife’s will, the<br />

childless Wilsdorf transferred his shares of<br />

Montres Rolex SA to the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation,<br />

thus ensuring that his business would<br />

outlive him. Establishing the foundation also<br />

entailed the hiring of two additional directors.<br />

This finally gave Wilsdorf free time for extended<br />

journeys to meet with customers in Africa,<br />

South America, and the U.S.A.<br />

The gigantic Rolex Festival, which lasted for<br />

several days in 1951, celebrated the 70th<br />

birthday of the beloved patron. It also commemorated<br />

his 50 years in the service of time<br />

measurement, the 25th anniversary of the<br />

Oyster case, and the 20th anniversary of the<br />

<strong>ROLEX</strong>’S BIG BREAKTHROUGH CAME WITH<br />

<strong>THE</strong> LAUNCH OF <strong>THE</strong> WORLD’S FIRST WATER-RESISTANT<br />

WRISTWATCH IN 1926.<br />

“Perpetual” rotor winding system. At this<br />

time, Rolex already had subsidiaries in Bombay,<br />

Brussels, Buenos Aires, Dublin, Havana, Johannesburg,<br />

London, Milan, Mexico City, New<br />

York, Paris, Sao Paulo and Toronto. Rolex provided<br />

workspace for some 400 employees in<br />

Geneva. Payrolls from the early 1960s list<br />

roughly 250 people on the staff in Biel.<br />

Wilsdorf didn’t live long enough to witness<br />

his firm’s unavoidable move into a new building<br />

on Rue François-Dussaud. This building,<br />

which is surrounded by a manmade watercourse,<br />

opened in 1965, roughly five years after<br />

Hans Wilsdorf passed away on July 6, 1960<br />

in Escale Fleurie, his summer home on the<br />

southern shore of Lake Geneva.<br />

Wilsdorf insisted that all Rolex movements<br />

be good enough to earn official rate certificates.<br />

No fewer than 48,347 of the 54,799<br />

certificates issued prior to 1944 were awarded<br />

to Rolex chronometers. The firm was awarded<br />

its 50,000th rate certificate in 1945, the same

<strong>ROLEX</strong><br />

year that Rolex celebrated its 40th anniversary.<br />

In a letter dated June 4, 1962, the watch-testing<br />

facilities confirmed that Rolex had already<br />

passed the magic number of 500,000 certificates.<br />

This was reason enough to now award<br />

the Red Seal, which had previously been given<br />

to all Rolex chronometers, only to specimens<br />

that had performed with “especially good results”<br />

in the official tests. As the years went by,<br />

the numbers continued to grow. Rolex cele-<br />

Rolex as a Foundation<br />

Wilsdorf transferred his shares of Montres Rolex<br />

SA to the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation in 1945.<br />

The foundation remains the owner of Rolex<br />

Geneva today. Wilsdorf even specified precise instructions<br />

for the distribution of dividends. A major<br />

portion of the money was to be donated to<br />

charity, a purpose that was fully in accord with the<br />

wishes of his deceased wife, who had frequently<br />

accompanied her husband to the office. Institutions<br />

in Geneva which benefit from Wilsdorf’s<br />

generosity include the school of watchmaking,<br />

the academy of fine arts, and the faculty for busi-<br />

58 WatchTime October <strong>2004</strong><br />

Rolex is the<br />

greatest pioneer in<br />

the testing of<br />

wristwatches for<br />

chronometer certification.<br />

The illustration<br />

shows rate<br />

certificates from<br />

1933 and 1965.<br />

brated its millionth chronometer in 1968, its<br />

two-millionth in 1973, and its ten-millionth officially<br />

certified chronometer in 1990. Rolex<br />

manufactured 814,720 of the 1,271,934<br />

movements tested by the C.O.S.C. in 2002.<br />

Although Rolex doesn’t release the exact statistics,<br />

it seems likely that the number of officially<br />

tested wristwatch chronometers with<br />

mechanical movements is slowly but surely<br />

nearing the 20-million mark – a unique record<br />

ness and social sciences at the university. The<br />

Swiss watch-research laboratory in Neuchâtel<br />

also receives Wilsdorf’s largesse. Donations from<br />

his foundation helped build a language library for<br />

the blind, a laboratory at the new school of<br />

watchmaking and an exhibition pavilion in<br />

Lucerne for the animal-protection league. The<br />

foundation also made available numerous radios<br />

and film projectors for charitable purposes. Finally,<br />

talented graduates from vocational schools in<br />

Geneva are eligible for awards and prizes from<br />

the foundation.<br />

that no other manufacture can even come<br />

close to challenging. The many records that<br />

Rolex has set in such tests prove what horological<br />

meticulousness can accomplish when applied<br />

to comparatively small wristwatch calibers.<br />

Nothing can take the place of wellthought-out<br />

construction, precise production,<br />

high-quality materials, and painstaking final<br />

quality-control checks.<br />

These wristwatches had to earn their enviably<br />

good reputation, not only for the accuracy<br />

of their rates, but also for their resistance to<br />

water. The edges of the crystal and the back of<br />

the case are critical locations, especially on a<br />

model with an angular case. The crown and its<br />

stem are also weak links in the water-resistance<br />

chain. Rolex was well aware of these<br />

facts. In the mid 1920s, at a time when wristwatches<br />

commanded only a 35% share of the<br />

market for portable timepieces, the young<br />

business set its sights on finding a once-andfor-all<br />

solution to the problem of leaky cases.<br />

Wilsdorf had first turned his attention to<br />

this crucial theme years before. An early step

<strong>ROLEX</strong><br />

PR for the first water-resistant wristwatch:<br />

swimmer Mercedes Gleitz…<br />

in the right direction had been the use of<br />

screw-in cases made by Dennison Watch<br />

Case. These cases are readily identifiable by<br />

the fluting on the rims of their crystals and<br />

backs. This channeling makes both components<br />

easy to grasp so that they can be<br />

screwed to the middle part of the case. This<br />

60 WatchTime October <strong>2004</strong><br />

…swam across the English Channel with an<br />

Oyster on her wrist.<br />

visible attribute continues to distinguish the<br />

backs of Rolex watches today.<br />

Wilsdorf relied on a purely mechanical construction<br />

without problematic materials. His formula<br />

for success can be summarized as follows:<br />

1. a hermetically sealed case, each part of<br />

which is screwed water-resistant;<br />

An early advertisement<br />

for the Rolex Oyster.<br />

The first<br />

Rolex Oyster<br />

from 1926.<br />

2. a new and perfectly form-fitting crystal<br />

made of synthetic material; and<br />

3. a crown that lastingly protects the movement<br />

against moisture penetration, even if the<br />

crown is operated daily.<br />

Wilsdorf purchased the rights to use an<br />

idea that had originally occurred to Georges<br />

Peret and Paul Perregaux. In October 1925,<br />

these two men became the first watchmakers<br />

to screw a crown onto a watch’s case. Rolex<br />

applied for a patent on a threaded case on<br />

September 21, 1926. Another application followed<br />

on October 18, this time for patent protection<br />

on a crown that was screwed to the<br />

middle part of the case. Corresponding<br />

patents were soon granted in Switzerland and<br />

Great Britain. There wasn’t much need for research<br />

because Rolex’s revolutionary inventions<br />

were entirely unprecedented. All that<br />

was missing was a catchy name to aptly express<br />

the characteristic attribute of the new<br />

case. After considering several possibilities, the<br />

name was chosen: “Oyster.”<br />

The first official appearance by the Oyster<br />

came soon thereafter. Mercedes Gleitze, a<br />

young stenographer from London, swam<br />

across the English Channel in the record-breaking<br />

time of just 15 hours and 15 minutes on October<br />

7, 1927. Afterwards, she showed her<br />

perfectly functioning Rolex to a crowd of astonished<br />

reporters. To publicize this sensational<br />

achievement, Wilsdorf ran a full-page ad on<br />

the front page of the Daily Mail. Although the<br />

ad cost Rolex a king’s ransom, more than 2 million<br />

readers saw the ad when the newspaper<br />

was published on November 24, 1927.<br />

Wilsdorf supplied his dealers with small,<br />

patented aquariums to display in their shop<br />

An Oyster model<br />

from 1928.

<strong>ROLEX</strong><br />

Healthy evolution: the first Datejust from 1945 (Ref. 4467, far left) combined all the Rolex virtues.<br />

Models from the 1970s are shown in the center and at the right.<br />

windows. Inside each aquarium, a ticking Oyster<br />

continued to show the correct time while a<br />

goldfish swam placidly all around it. Advertising<br />

campaigns featuring popular actresses and<br />

the Oyster’s participation in attention-getting<br />

pioneering airplane flights (where the watches<br />

successfully withstood severe temperature<br />

variations, extreme vibrations, and plenty of<br />

dust) further contributed to Rolex’s ever-growing<br />

renown.<br />

Despite patent protection, Rolex was soon<br />

obliged to defend itself against imitators. Legal<br />

proceedings were initiated in 1934 against the<br />

Schmitz Brothers case factory in Grenchen,<br />

Advertisement for the first Datejust.<br />

62 WatchTime October <strong>2004</strong><br />

Germany. After two-and-a-half -years of litigation,<br />

judges at a Swiss court unanimously<br />

agreed on July 8, 1937 that Schmitz Brothers<br />

owed compensatory damages to Rolex. The<br />

verdict made it clear that although Wilsdorf<br />

had not invented the concept of the water-resistant<br />

wristwatch, he was the first person to<br />

translate the idea into practical reality via industrial<br />

manufacturing methods. In this context, it<br />

became known that Rolex had invested 1.2 million<br />

Swiss francs in the launch and distribution<br />

of the Oyster case, thus formatively contributing<br />

to the growth of people’s confidence in water-resistant<br />

wristwatches and opening new<br />

markets for the entire watch industry. Roughly<br />

200,000 Swiss-made water-resistant wristwatches<br />

were sold in 1935-1936 alone.<br />

In 1926, Wilsdorf’s foresight had helped<br />

him identify another problem that beset wristwatches,<br />

one that still hadn’t been solved in<br />

the early 1930s. Of course, it was easy to hermetically<br />

reseal a crown once it had been<br />

pushed back in after winding the mainspring,<br />

but one instant of forgetfulness could render<br />

useless all of the hard work and ingenuity that<br />

Rolex had incorporated into a water-resistant<br />

wristwatch. What Rolex needed was a selfwinding<br />

movement that would eliminate the<br />

need for manual daily winding.<br />

Wilsdorf and his technical staff in Biel had<br />

defined the basic idea for a “Perpetual” in<br />

1930: “The invention of an automatic winding<br />

mechanism that moves back and forth silently,<br />

smoothly, and without a buffer.” This idea, of<br />

course, hadn’t materialized out of thin air.<br />

Wilsdorf described its background in his autobiography:<br />

“The logical consequence of the<br />

Rolex Oyster was the creation of an automatic<br />

watch whose movement would repeatedly<br />

wind itself on its own, thus ensuring that the<br />

timepiece would continue to run uninterruptedly.”<br />

The Rolex team based their research on<br />

the work of Abraham Louis Perrelet, Sr. (1729-<br />

1826), a self-taught watchmaker<br />

who had successfully experimented<br />

with a rotor in<br />

1770.<br />

The new Rolex Perpetual<br />

ticked satisfactorily in every respect in 1931.<br />

The advantages of the Perpetual didn’t<br />

lie solely in its rotating weight; the<br />

modular construction with a sepa-<br />

The Perpetual selfwinding<br />

model.<br />

Scarcely changed on the outside:<br />

a Datejust from 1988.

Rolex’s headquarters on Rue François-Dussaud in Geneva.<br />

rate group of components for the automatic<br />

winding mechanism can also be regarded as a<br />

trailblazing innovation. Modular architecture<br />

meant that it wasn’t necessary to disassemble<br />

the entire movement whenever the winding<br />

system required servicing. To guard against<br />

over-winding, a safety mechanism consisting<br />

of a slip-spring prevented the system from<br />

over-tightening and ultimately snapping the<br />

steel mainspring.<br />

Wilsdorf still had to market the new watch,<br />

and encountered many jewelers and watch<br />

merchants who still remembered their bad experiences<br />

with the Harwood; the first serially<br />

manufactured self-winding wristwatch. Fortunately<br />

for Wilsdorf, his was a much better<br />

<strong>2004</strong>: The Latest Models<br />

The new Datejust models<br />

for <strong>2004</strong> include (left)<br />

Ref. 116 238 in yellow<br />

gold ($17,250). Bigger<br />

hands distinguish the<br />

newcomers. The rehaut<br />

has also been updated:<br />

it’s now engraved with<br />

the brand’s name and (at<br />

the “6”) the individual<br />

case number. The same<br />

details apply for the<br />

Turn-O-Graph (right),<br />

Ref. 116 264 in stainless<br />

steel with rotating white<br />

gold bezel ($5,425).<br />

64 WatchTime October <strong>2004</strong><br />

watch in every respect, and eventually the Perpetual’s<br />

inherent excellence, coupled with<br />

well-targeted advertising campaigns, overcame<br />

any hesitations.<br />

The 15 years of the original patent protection<br />

came to an end in 1948, but Rolex still<br />

held a commanding lead over nearly all its<br />

competitors. After all, for the past decade and<br />

a half, rotor winding and other refinements in<br />

Rolex’s Perpetual had been off limits to them.<br />

Only after 1948 were competitors permitted<br />

to introduce their own systems. Rolex wanted<br />

to debut a date display watch to mark the<br />

firm’s 40th birthday in 1945. The Datejust (caliber<br />

740) was a world’s first, becoming an archetype<br />

that would influence the technology<br />

Four decades of continuity: André J. Heiniger<br />

(1921-2000) led Rolex from 1963 to 1992,<br />

when his son Patrick Heiniger took the reins.<br />

and appearance of generations of subsequent<br />

watches. The watch’s name was carefully selected:<br />

“Date” is self-explanatory, while “Just”<br />

stands for “just in time.” And this means that<br />

the date display advances to show the next<br />

day’s date without delay at midnight. The<br />

watch was the world’s first fully water-resistant<br />

men’s wristwatch with automatic rotor winding,<br />

central seconds, and window-type date<br />

display whose accurate rate was verified by an<br />

official chronometer certificate.<br />

The Datejust featured a central secondshand<br />

and a readily legible date display inside a<br />

window at the “3,” a location chosen for a<br />

very good reason: most people wear a wristwatch<br />

on their left wrist, so the date display at<br />

the “3” is the first indicator that comes into<br />

view when the timepiece peeks out from under<br />

your shirt cuff.<br />

WatchTime would like to thank Wempe<br />

Jewelers for granting us permission to<br />

reprint portions of Gisbert L. Brunner’s upcoming<br />

book on Rolex.