Augustine (354–430) handout #1 – On Free Choice of Will, Book 1

Augustine (354–430) handout #1 – On Free Choice of Will, Book 1

Augustine (354–430) handout #1 – On Free Choice of Will, Book 1

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Augustine</strong> (<strong>354<strong>–</strong>430</strong>) <strong>handout</strong> <strong>#1</strong> <strong>–</strong> <strong>On</strong> <strong>Free</strong> <strong>Choice</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Will</strong>, <strong>Book</strong> 1 Phil 201 <strong>–</strong> Dr. Tobias H<strong>of</strong>fmann<br />

<strong>Augustine</strong>, <strong>On</strong> <strong>Free</strong> <strong>Choice</strong> <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Will</strong>, trans. Th. <strong>Will</strong>iams, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1993.<br />

Q. Is God the cause <strong>of</strong> evil? (<strong>Book</strong>s 1<strong>–</strong>3, pp. 1ff.)<br />

A. God does no [moral] evil, but he punishes the wicked and thus causes the evil <strong>of</strong> punishment. When people<br />

do evil, they are the cause <strong>of</strong> their own evildoing (1.1, p. 1).<br />

Q. Did we learn how to sin (i. e. to do evil)? (1.1, p. 1)<br />

A. Learning is good, therefore we do not learn evil (1.1, pp. 1<strong>–</strong>3)<br />

Q. What is the source <strong>of</strong> our evildoing? Can we trace back our sins to God? <strong>–</strong> If the sins come from our<br />

souls, and our souls come from God, do our sins indirectly come from God? (1.2, pp. 3<strong>–</strong>28; <strong>Book</strong>s 2<strong>–</strong>3)<br />

Q. What is evildoing? (1.3, pp. 4<strong>–</strong>28)<br />

A. (Preliminary answer:) evildoing is inordinate desire (= cupidity) (1.3, pp. 5<strong>–</strong>6). Inordinate desire is<br />

“the love <strong>of</strong> those things that one can lose against one’s will” (1.4, p. 8).<br />

Q. Is all evildoing due to inordinate desire? For instance, when you kill someone, is this due to<br />

inordinate desire? (1.4, p. 7) Can you kill someone out <strong>of</strong> self-defense? (1.5, p. 8)<br />

Q. By which criteria can we decide when killing is allowed and when not?<br />

A. This is established by the law (1.5, p. 8).<br />

There are two laws: the eternal law and the temporal law (1.6, pp. 11<strong>–</strong>12, 24<strong>–</strong>28). Both laws are<br />

good (“an unjust law is no law at all”, 1.5, p. 8). Both guarantee a perfect order (“live perfectly!”).<br />

Q. What does it mean to live perfectly, according to both laws? (1.7, p. 12)<br />

Q. Do we merely live (like animals) or do we also know that we are alive (i. e.: do we have<br />

reason)? (1.7, p. 12).<br />

A. Humans possess reason, animals do not. Thus humans have the possibility to not<br />

merely live, but to live with reason and understanding. Not only do we live, but we can<br />

live well.<br />

A. Consequently, humans live well when the impulses <strong>of</strong> the soul [emotions, passions, desires,<br />

fears, angers] are guided by reason (1.8, p. 14).<br />

If reason rules, the person is wise, if not, he is a fool. Human wisdom consists in the rule<br />

<strong>of</strong> the mind (1.9, pp. 15<strong>–</strong>16). It is possible, that the mind does not rule (1.10, p. 16).<br />

Q. How is it possible that the mind does not rule? How can inordinate desire overpower<br />

the mind? (1.10, p. 16)<br />

A. “The conclusions that we have reached thus far indicate that a mind that is in control,<br />

one that possesses virtue, cannot be made slave to inordinate desire by anything equal<br />

or superior to it, because such a thing would be just, or by anything inferior to it, because<br />

such a thing would be too weak. Just one possibility remains: only its own will<br />

and free choice can make the mind a companion <strong>of</strong> cupidity.” (1.11, p. 17)<br />

Q. How is this free choice possible? (1.12, p. 18).<br />

Q. Do we have a [free] will? Do we have a good will? (1.12, pp. 19ff.)<br />

Q. What is a good will?<br />

A. “It is a will by which we desire to live upright and honorable lives and to<br />

attain the highest wisdom.” A good will is worth more than wealth or<br />

honor or physical pleasures. (1.12, p. 19).<br />

A. It is in the will’s own power to be good or bad. Thus it is up to us whether we<br />

are good or bad, and whether we desire things that we can lose (power,<br />

wealth, pleasure, 1.12, p. 20) or that we cannot lose (a good will and the virtues,<br />

1.13, pp. 20<strong>–</strong>21, cf. 1.5, p. 9).<br />

Q. [Does a good will provide a happy life?]<br />

A. A good will allows us to have the virtues <strong>of</strong> prudence, fortitude, temperance<br />

and justice; possessing these virtues makes our life happy (1.13, pp. 20<strong>–</strong>22).<br />

Therefore, it lies in our own will’s power to be happy or not (1.13, p. 22).<br />

Q. If this is so, why doesn’t everyone attain a happy life? (1.14, pp. 23f.)<br />

A. It is not enough to will to be happy, but you must will it in the right way <strong>–</strong><br />

you must deserve happiness (“merit”) (1.14, p. 23).<br />

Q. How do these considerations about the will relate to the law? (1.15, p. 24)<br />

A. Those who love eternal things (and thus are happy) live under the eternal law, while those<br />

who love temporal things (and thus are unhappy) live under the temporal law (1.15,<br />

p. 25).<br />

A. Evildoing is neglecting eternal things and pursuing temporal things (1.16, p. 27).<br />

A. “[W]e do evil by the free choice <strong>of</strong> our will.” (1.16, p. 27).

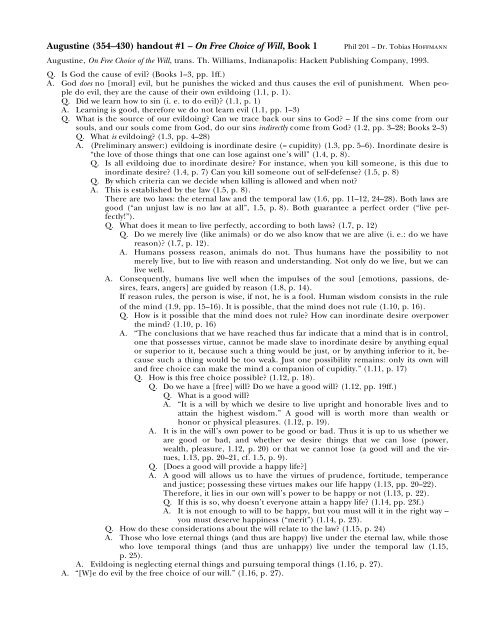

The Eternal and the Temporal Law (<strong>Book</strong> 1, sections 5<strong>–</strong>6 & 15<strong>–</strong>16, pp. 8<strong>–</strong>12 & 24<strong>–</strong>28)<br />

Eternal law Temporal law(s)<br />

• unchangeable [and it is valid everywhere]<br />

• “it the law according to which it is just<br />

that all things be perfectly ordered”<br />

• is stamped upon our minds (1.6, p. 11)<br />

• commands that the soul should be ruled<br />

by reason (1.8, p. 14)<br />

• Example: “Human life may not be endangered”<br />

• can change [and is different in different<br />

countries]<br />

• determined by human beings (the people,<br />

the magistrates etc.)<br />

• must be derived from the eternal law,<br />

i.e. it must be in accord with eternal law,<br />

and in accord with reason<br />

• must be just (p. 8)<br />

• preserves peace & human society (p. 25)<br />

• Example: “Speed limit = 65mph.<br />

Life under the eternal law Life under the temporal law<br />

• those who love eternal things (a good<br />

will and the virtues)<br />

• happy life<br />

• it commands to “purify your love by<br />

turning it away from temporal things<br />

and toward what is eternal”<br />

• driving force: love.<br />

• those who love temporal things<br />

• unhappy life<br />

• it commands to possess temporal things<br />

in such a way that peace and human society<br />

are preserved: body, freedom (as<br />

having no human masters), parents /<br />

siblings / spouse / friends, city, property<br />

• driving force: fear (<strong>of</strong> punishment, i. e.<br />

taking away some temporal goods).<br />

Good use <strong>of</strong> temporal things Bad use <strong>of</strong> temporal things<br />

“We should not find fault with silver and<br />

gold because <strong>of</strong> the greedy, or food because<br />

<strong>of</strong> gluttons, or wine because <strong>of</strong><br />

drunkards, or womanly beauty because <strong>of</strong><br />

fornicators and adulterers, and so on, especially<br />

since you know that fire can be used<br />

to heal and bread to poison.” (1.15, p. 26)<br />

Eternal law: perfect order <strong>of</strong> all<br />

things. General command: “live perfectly”<br />

(do the good, avoid evil)<br />

Temporal law: live perfectly<br />

by obeying the laws <strong>of</strong> your<br />

country.<br />

“Someone who uses them [i. e. the temporal<br />

goods] badly clings to them and becomes<br />

entangled with them. He serves things that<br />

ought to serve him, fixing on goods that he<br />

cannot even use properly because he is not<br />

himself good.” (1.15, p. 26)