- Page 1 and 2:

MEDICARE, MEDICAID, & HEALTH REFORM

- Page 3 and 4:

GENERAL INFORMATION TABLE OF CONTEN

- Page 5 and 6:

Last Updated: November 12, 2012 2.

- Page 7 and 8:

Ref. # 2. Task/Issue Person(s) CMS

- Page 9 and 10:

Ref. # II. POLICY Task/Issue Person

- Page 11 and 12:

Ref. # Task/Issue Person(s) 9. Stra

- Page 13 and 14:

Ref. # Task/Issue Person(s) 15. Eva

- Page 15 and 16:

IV. OUTREACH AND EDUCATION MMPC: SU

- Page 17 and 18:

Ref. # Task/Issue Person(s) 25. Med

- Page 19 and 20:

MMPC October 9, 2012 Teleconference

- Page 21 and 22:

To do List: -Myra will have draft b

- Page 23 and 24:

Internal Revenue Service Meeting No

- Page 25 and 26:

with a “interim/acting”. Can al

- Page 27 and 28:

8/7/12 DRAFT COMPANION TO ADDENDUM

- Page 29 and 30:

Indian Self-Determination and Educa

- Page 31 and 32:

Under federal law, There are privac

- Page 33 and 34:

1. Purpose of Addendum; Supersessio

- Page 35 and 36:

(1) ISDEAA, 25 USC §450 et seq.; (

- Page 37 and 38:

13. Medical Quality Assurance Requi

- Page 39 and 40:

edits on documents are due back fro

- Page 41 and 42:

d. CCIIO Philosophy - CCIIO is taki

- Page 43 and 44:

- I/T/U provider receives their all

- Page 45 and 46:

i. CMS rep. commented that an analy

- Page 47 and 48:

IHS TRIBAL SELF-GOVERNANCE ADVISORY

- Page 49 and 50:

Letter: Dr. Robert Petzel, Under Se

- Page 51 and 52:

October 17, 2012 Dr. Robert Petzel,

- Page 53 and 54:

A BILL To correct inconsistencies i

- Page 55 and 56:

California Rural Indian Health Boar

- Page 57 and 58:

As people have changes in employmen

- Page 59 and 60:

Indian eligibility determinations,

- Page 61 and 62:

v.7, 2012‐09‐23a ACA, (2) the s

- Page 63 and 64:

Indian tribe means any Indian tribe

- Page 65 and 66:

v.7, 2012‐09‐23a In issuing thi

- Page 67 and 68:

(1) to ensure the highest possible

- Page 69 and 70:

v.7, 2012‐09‐23a Delays in acc

- Page 71 and 72:

v.7, 2012‐09‐23a 1997. The prov

- Page 73 and 74:

v.7, 2012‐09‐23a 48 Enacted thr

- Page 75 and 76:

Prepared by James Crouch MPH Chair,

- Page 77 and 78:

Summary T he Indian Health Service

- Page 79 and 80:

Summary providers that were either

- Page 81 and 82:

Introduction Reliable determination

- Page 83 and 84:

Analysis Groups IHS AIAN Methods Th

- Page 85 and 86:

Methods group for the statistical m

- Page 87 and 88:

Enrollees with no Payments Methods

- Page 89 and 90:

Methods Table 5. Mean Medicaid and

- Page 91 and 92:

Restricted Benefits Methods Enrolle

- Page 93 and 94:

Age and Sex Methods Medical care pa

- Page 95 and 96:

Methods Table 9. Findings for all s

- Page 97 and 98:

Methods Map 1. 12 IHS Areas: Contra

- Page 99 and 100:

Findings Figure 1. Adjustment of Me

- Page 101 and 102:

Findings Payments are Higher for IH

- Page 103 and 104:

Findings for Group 3 was $600 and W

- Page 105 and 106:

Findings Unadjusted mean payments f

- Page 107 and 108:

Findings Table 10. Unadjusted Mean

- Page 109 and 110:

Findings Figure 13. Adjusted Mean T

- Page 111 and 112:

Analysis Group Compiled Findings fo

- Page 113 and 114:

Findings Adjusted Mean Payments for

- Page 115 and 116:

Findings Figure 18. Percent differe

- Page 117 and 118:

Findings providers for services nee

- Page 119 and 120:

Findings Figure 21. Medicaid Altern

- Page 121 and 122:

Conclusions and Recommendations pro

- Page 123 and 124:

Indian Health Service, 2012. Federa

- Page 125 and 126:

Tribal Consultation Policy HHS 1. P

- Page 127 and 128:

defined in Sections 8 and 9 of this

- Page 129 and 130:

2. Office of Intergovernmental Affa

- Page 131 and 132:

will give equal consideration to th

- Page 133 and 134:

provide Indian Tribes with a region

- Page 135 and 136:

4. Each Operating Division Head/Dep

- Page 137 and 138:

Department’s ability to address i

- Page 139 and 140:

17. Sovereignty - The ultimate sour

- Page 141 and 142:

1. Selection of workgroup co-chairs

- Page 143 and 144:

It is unclear if this was just an o

- Page 149 and 150:

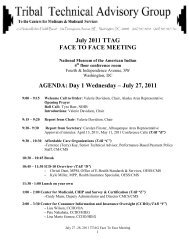

November 14 -15, 2012 TTAG FACE TO

- Page 151 and 152:

AGENDA: Day 2 Thursday - Nov. 15, 2

- Page 153 and 154:

Subpart G--Social Services Block Gr

- Page 155 and 156:

organization applying for or receiv

- Page 157 and 158:

members of a tribe receiving direct

- Page 159 and 160:

is at or below the poverty line. (d

- Page 161 and 162:

under this part. Grantees that rece

- Page 163 and 164:

income home energy assistance progr

- Page 169 and 170:

Need for Uniform Operational Guidan

- Page 171 and 172:

Dear Tribal Representatives, Octobe

- Page 173 and 174:

There is a strong correlation betwe

- Page 175 and 176:

Wed. Nov 14 th : SDPI National Call

- Page 177 and 178:

Future MMPC Meetings & Conference C

- Page 179 and 180:

Regulation Review and Impact Analys

- Page 181 and 182:

64. Policy on Conferring with Urban

- Page 183 and 184:

RRIAR Ref. # 1.c. 8. 9. 13. Short T

- Page 185 and 186:

RRIAR Ref. # 20. 23. 26. 28.a. Shor

- Page 187 and 188:

RRIAR Ref. # 43. 44. 46. 61. Short

- Page 189 and 190:

RRIAR Ref. # 83. 84. 85. 86. Short

- Page 191 and 192:

RRIAR Ref. # 2.c. 2.d. 3.a. Short T

- Page 193 and 194:

RRIAR Ref. # 4.b. 5. 10.a. 10.b. Sh

- Page 195 and 196:

RRIAR Ref. # 11.e. 11.f. 11.g. Shor

- Page 197 and 198:

RRIAR Ref. # 22. 24. 25.a. Short Ti

- Page 199 and 200:

RRIAR Ref. # 52.a. 52.b. 52.c. 57.

- Page 201 and 202:

RRIAR Ref. # 60.b. 60.c. 60.d. Shor

- Page 203 and 204:

RRIAR Ref. # 71.b. 72. 73. Short Ti

- Page 205 and 206:

RRIAR Ref. # 6.b. 6.c. 7.a. Short T

- Page 207 and 208:

RRIAR Ref. # 7.e. 7.f. 7.g. 12.a. S

- Page 209 and 210:

RRIAR Ref. # 29. 31.a. 31.b. 31.c.

- Page 211 and 212:

RRIAR Ref. # 39. 42. 45. 47. Short

- Page 213 and 214:

RRIAR Ref. # 54. 56. 63. 64. Short

- Page 215 and 216:

RRIAR Ref. # 69. 77. 88. Short Titl

- Page 217 and 218:

RRIAR Ref. # 92. 35. 36. 74. Short

- Page 219 and 220:

RRIAR Ref. # 94. 95. 96. 97. Short

- Page 221 and 222:

premium tax credit assistance and c

- Page 223 and 224:

Access to this benefit is criticall

- Page 225 and 226:

community providers for purposes of

- Page 227 and 228:

November 12, 2012 Centers for Medic

- Page 229 and 230:

_________ American Indian or Alaska

- Page 231 and 232:

November 9, 2012 Page 2 We are comm

- Page 233 and 234:

Tribal Consultation for Health Insu

- Page 235 and 236:

Background Analysis of Tribal Consu

- Page 237 and 238:

Analysis of Tribal Consultation Pol

- Page 239 and 240:

Analysis of Tribal Consultation Pol

- Page 241 and 242:

Analysis of Tribal Consultation Pol

- Page 243 and 244:

Analysis of Tribal Consultation Pol

- Page 245 and 246:

Analysis of Tribal Consultation Pol

- Page 247 and 248:

Analysis of Tribal Consultation Pol

- Page 249 and 250: Analysis of Tribal Consultation Pol

- Page 251 and 252: D. FFE Data Analysis of Tribal Cons

- Page 253 and 254: John O'Brien Director, Healthcare &

- Page 255 and 256: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 257 and 258: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 259 and 260: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 261 and 262: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 263 and 264: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 265 and 266: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 267 and 268: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 269 and 270: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 271 and 272: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 273 and 274: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 275 and 276: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 277 and 278: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 279 and 280: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 281 and 282: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 283 and 284: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 285 and 286: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 287 and 288: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 289 and 290: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 291 and 292: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 293 and 294: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 295 and 296: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 297 and 298: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 299: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 303 and 304: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 305 and 306: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 307 and 308: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 309 and 310: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 311 and 312: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 313 and 314: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 315 and 316: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 317 and 318: Draft Report: Currently being circu

- Page 319 and 320: Draft Report: Currently being circu