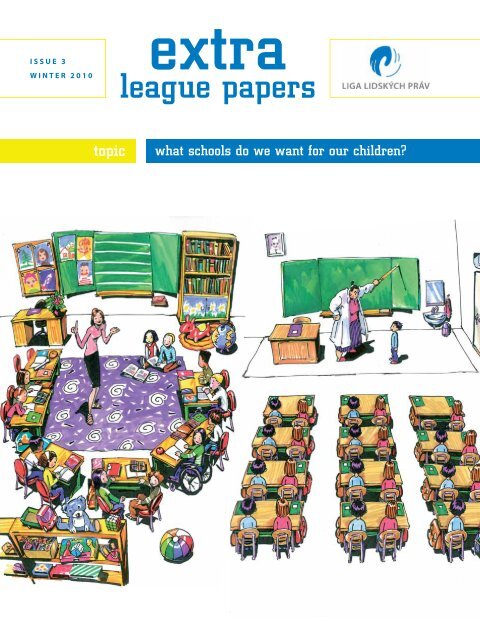

EXTRA league papers | issue 3 | winter 2010 | What Schools Do We Want for our Children?

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ISSUE 3<br />

WINTER <strong>2010</strong><br />

topic<br />

extra<br />

<strong>league</strong> <strong>papers</strong><br />

what schools do we want <strong>for</strong> <strong>our</strong> children?

2<br />

introduction<br />

Olga Kusá, educational specialist in the Inclusive<br />

Education Support Centre in Brno<br />

we should have<br />

diversity in<br />

schools… or did i<br />

go mad?<br />

I like my job. I really do. Thanks to my<br />

job I got to know those schools where<br />

diversity is accepted, respected and<br />

even welcomed as good experience and<br />

benefi cial <strong>for</strong> all. But just like all other<br />

jobs it has its dark side that can get on<br />

my nerves!<br />

Have you ever wondered how some people<br />

can be so thick-headed? Have you ever felt you<br />

were the only one trying to make something<br />

happen? Have you ever felt like exploding<br />

because you were being told again and again<br />

why some things cannot be done instead of<br />

trying to fi nd solutions? <strong>What</strong> can surely make<br />

me see red is the stiff ness of opinions of education<br />

workers whose simplifying and black<br />

and white judgements aff ect the education of<br />

“diff erent” children. Psychologists and specialized<br />

teachers are the ones who establish the<br />

“diagnosis”, on which basis a child is recommended<br />

<strong>for</strong> integration into a regular school or<br />

sent to a special school. Educational counsellors<br />

cooperate with teachers and advise them<br />

how to work with children who have a learning<br />

disability. These people can have an essential<br />

impact on the future of children and their authority<br />

can aff ect the minds of teachers. I have<br />

recently had an opportunity to participate in<br />

a discussion between educational counsellors<br />

and teachers at a standard elementary school.<br />

The subject of the discussion was the education<br />

of so-called problematic pupils. I was happy<br />

about the event, I was interested in the problems<br />

teachers had and curious to know how<br />

the educational counsellors would deal with<br />

the multitude of questions and complaints.<br />

But to my bitter disappointment, at the very<br />

beginning the lead psychologist unblinkingly<br />

said: “It is a shame that it is no longer allowed to<br />

send border children to <strong>for</strong>mer special schools.<br />

Such children will now come fl ooding into y<strong>our</strong><br />

schools! I am really curious to see how you will<br />

manage it.”<br />

Imagine my despair, my job is to motivate teachers<br />

not to give up on and get rid of less able<br />

children, no matter how diffi cult the work with<br />

them can be. “Border children” is a simplifi ed<br />

term describing children whose results in IQ<br />

tests border on mild intellectual disabled. These<br />

children do not do well in school and there<br />

are many reasons why it is so. However, I think<br />

that these children do not belong to schools<br />

<strong>for</strong> the intellectually disabled.<br />

Nevertheless, the discussion goes on. And with<br />

it come other shocking words spoken by an<br />

educational counsellor: “It is time we really started<br />

to fear children with behavi<strong>our</strong>al disorders,<br />

as their number rises. An unruly child cannot be<br />

changed, nothing works <strong>for</strong> them.”<br />

But the best of educational optimism is yet to<br />

come: “There is nothing you can do with border<br />

children; they will not start getting better. Let<br />

them fail the end of year exams and they might<br />

end up at a special school anyway.”<br />

This experience was stuck in my head long afterwards<br />

and I was thinking about the psychologist.<br />

A change can be diffi cult and attitudes<br />

are especially hard to change. Maybe she has<br />

twenty or thirty years of experience, feels sure<br />

about what she does and nothing can easily<br />

surprise her. “It has been working fi ne until now,<br />

so what do you want?!” “A change?” I ask. Or did<br />

I really go mad?<br />

Lucie Obrovská, lawyer of the Equal Opportunities<br />

Department of the Offi ce of the Public Defender<br />

of Rights<br />

three year “anniversary”<br />

of the<br />

d. h. verdict: have<br />

we moved on?<br />

The Czech Republic has committed to<br />

ensuring equal access to education. Since<br />

last year this right has been grounded<br />

not only in the Charter of fundamental<br />

rights and basic freedoms, education<br />

rules and international obligations but<br />

also in the Anti-discrimination Act.<br />

When non-governmental organizations recently<br />

criticized the Minister of Education <strong>for</strong> his<br />

indifference towards the <strong>issue</strong> of integration<br />

and inclusion, they pointed out the possibility<br />

of another action being brought against the<br />

Czech Republic at the European C<strong>our</strong>t of Human<br />

Rights in Strasb<strong>our</strong>g. In 2007 in the case of D.<br />

H. and others vs. the Czech Republic the same<br />

c<strong>our</strong>t stated that we discriminate against Roma<br />

children because we do not provide them with a<br />

standard quality education, i.e. education given<br />

to non-Roma children. Instead, a great number<br />

of Roma children are placed in non-standard<br />

schools. But according to the current legislation,<br />

only disabled children should be provided with<br />

such education. In <strong>We</strong>stern countries it is quite<br />

common that emphasis is put on coeducation<br />

of all children, regardless of their disability. Inclusion<br />

is good not only <strong>for</strong> the education of the<br />

diff erent, disabled child but it also improves the<br />

child’s relationship with majority children, who<br />

thus learn tolerance.<br />

Special changes at special schools or<br />

Czech-style inclusion<br />

Although special schools were to be removed<br />

from the education system, anyone in this fi eld<br />

will confirm that the change of the schools’<br />

naming was merely symbolic. Special schools<br />

were renamed practical elementary schools but<br />

the change in the concept of education, which<br />

would support the inclusive approach, did not<br />

happen. It is appalling that three years later legal

epresentatives of Roma children can still claim<br />

compensation <strong>for</strong> an unequal access to education.<br />

Apart from this, they can also bring an action<br />

to c<strong>our</strong>t on the basis of the Anti-discrimination<br />

Act. For now, the use of the Act is rather scarce.<br />

<strong>We</strong> have to realize that the inclusive approach to<br />

education is not merely a moral challenge presented<br />

by some experts, parents or non-profi t<br />

organizations. The School Act itself supports an<br />

interpretation, which says that in cases in which<br />

it is benefi cial to the pupil to be included in the<br />

mainstream education this has to be done.<br />

One of the educational principles is an individual<br />

approach to every pupil and their educational<br />

needs. Apart from this, one of the education<br />

regulations explicitly states that in case of<br />

agreement with the child’s interests, the State is<br />

obligated to provide the child with a standard<br />

education. It is there<strong>for</strong>e necessary to incessantly<br />

remind people that the inclusive approach is<br />

not a surreal wish expressed by academics but<br />

that it is a legally binding concept, supported by<br />

the Strasb<strong>our</strong>g verdict and education rules.<br />

A so-called reintegration should be a natural<br />

part of the inclusive approach. The decision to<br />

place a child in a special school upon the recommendation<br />

of a psychologist should not be defi<br />

nite, on the contrary, they should be continuously<br />

watched and, if the situation changes, sent<br />

back to a standard elementary school. In addition,the<br />

teachers should be ready to provide the<br />

disabled children with appropriate support.<br />

Inclusion is <strong>for</strong> all, not only <strong>for</strong> Roma<br />

Non-governmental organizations, many experts<br />

and international institutions, including<br />

the European Commission against Racism and<br />

Intolerance are expressing alarm at the fact that<br />

the implementation of changes towards Roma<br />

education solutions has been stopped. The current<br />

Minister of Education refuses to support the<br />

changes that were prepared and partly implemented<br />

by the previous governments. <strong>We</strong> have<br />

to realize that the concept of inclusive education<br />

is much broader. It concerns not only Roma children<br />

but all disabled children as well. It includes<br />

quality education <strong>for</strong> ethnic minority children<br />

but it is also important to put maximum eff ort<br />

into integration of all children into standard<br />

schools and classes. The inclusive education system<br />

has the potential to off er quality education<br />

to any pupil but it also has a considerable socializing<br />

function at schools and in classes attended<br />

by mentally or physically disabled children and<br />

able-bodied children together.<br />

The Czech Republic is obligated to ensure the<br />

highest possible quality of education to all children,<br />

so it must be pointed out that the criticism<br />

on the part of organizations <strong>for</strong> protection of the<br />

human rights of disabled people is more than<br />

relevant. It is not a mere moral challenge but a<br />

serious legal obligation, which the State is obligated<br />

to fulfi l as the Czech Republic has ratifi ed<br />

the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with<br />

Disabilities. The discussion about insufficient<br />

integration of disabled children, of children from<br />

<strong>for</strong>eign families or otherwise disadvantaged<br />

children is there<strong>for</strong>e as relevant as the discussion<br />

about the education of Roma children.<br />

Verdict, and what is to follow?<br />

The fact that Roma children are discriminated<br />

against by the Czech Republic has been pointed<br />

out <strong>for</strong> a long time. That the education off ered<br />

in the <strong>for</strong>mer special schools does not provide<br />

adequate knowledge and skills needed to succeed<br />

at lab<strong>our</strong> market is beyond question. It is true<br />

that the Roma are very often unrightfully placed<br />

outside the mainstream. Non-standard education,<br />

i.e. education not at a regular elementary<br />

school, is intended <strong>for</strong> intellectually disabled<br />

children only. People with mild intellectual disability<br />

represent about 3 per cent of the population;<br />

it is there<strong>for</strong>e exceedingly disproportionate that 30<br />

per cent of Roma children are educated at <strong>for</strong>mer<br />

special schools. This fact had been pointed out<br />

by Czech non-governmental organizations long<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e the a<strong>for</strong>e-mentioned verdict was reached<br />

but un<strong>for</strong>tunately it had no impact on the actions<br />

taken by the Czech state authorities. This<br />

made the Strasb<strong>our</strong>g verdict, which emphasizes<br />

the human rights violation committed by the<br />

Czech Republic, all the more important. The<br />

c<strong>our</strong>t has repeatedly highlighted the segregation<br />

of the Roma, as it stated that neither Croatia<br />

nor Greece are able to provide equal educational<br />

opportunities <strong>for</strong> young Roma.<br />

The D. H. verdict puts emphasis on two essential<br />

aspects of the problem: (a) the lack of in<strong>for</strong>med<br />

consent of the Roma parents to their child’s<br />

placement outside the educational mainstream<br />

and (b) doubts as to the adequacy of tests<br />

used by pedagogical-psychological counselling<br />

centres. The c<strong>our</strong>t states that these tests are culturally<br />

prejudiced. This means that worse results<br />

achieved by Roma children do not stem from<br />

their own inability but from a diff erent cultural<br />

and social background. The c<strong>our</strong>t also believes<br />

that racial prejudices on the part of responsible<br />

people play an equally important role in sorting<br />

Roma children. This surely is a bold proclamation<br />

but if it is not true, we have to ask <strong>our</strong>selves,<br />

what causes the disproportionate number of<br />

Roma children at special schools.<br />

Has there been any change at all since the<br />

verdict was reached three years ago? The same<br />

Roma children who were placed outside the<br />

educational mainstream be<strong>for</strong>e the verdict, continue<br />

to be educated at these non-standard or<br />

“ghetto” schools. The work of pedagogical-psychological<br />

counselling centres did not undergo<br />

any considerable change either from the point<br />

of view of legislation or concerning personnel.<br />

This means that we still wrongfully send Roma<br />

children to such schools and classes that neither<br />

prepare them <strong>for</strong> everyday life nor provide them<br />

with quality education.<br />

<strong>What</strong> did the Czech School Inspectorate<br />

fi nd out?<br />

Exactly a year ago I carried out an analysis <strong>for</strong><br />

the Czech Helsinki Committee, in which I tried<br />

topic<br />

to assess the progress we made in following the<br />

“Strasb<strong>our</strong>g dictate”. One year later I must say<br />

that the situation has not improved although<br />

some changes have occurred. For example, the<br />

Czech School Inspectorate started to cooperate<br />

with non-governmental organizations and<br />

actively approached the burning questions<br />

concerning the education of the Roma and I<br />

was invited to participate in its investigations.<br />

Observations made at special schools confi rm<br />

what the non-governmental organizations have<br />

long been pointing out: that the representatives<br />

of special schools cannot be expected to show<br />

self-criticism and eff orts to reduce the number<br />

of children placed in special schools. It is an essential<br />

matter of their existence.<br />

But there were some aspects of the problem that<br />

the Inspectorate could not observe. It is impossible<br />

to exactly observe the parents’ consent to<br />

their child’s placement outside the educational<br />

mainstream although it is imposed by law. The<br />

legislation requires that in<strong>for</strong>med consent is<br />

obtained but in practice, parents are rarely in<strong>for</strong>med.<br />

However, in the near future a ministry<br />

guideline is to be <strong>issue</strong>d, which would deal with<br />

the question of in<strong>for</strong>med consent. Presently,<br />

it is the usual practice that the parent merely<br />

signs school-prepared documents as a sign of<br />

their consent. It is there<strong>for</strong>e difficult to assess<br />

to what extent the parents are in<strong>for</strong>med about<br />

the consequences of their child’s placement in a<br />

special school.<br />

Nevertheless, the Inspectorate could and did<br />

find out that the head teachers themselves<br />

violate the rules. Apart from the in<strong>for</strong>med consent,<br />

another condition of a child’s placement<br />

in a special school is a diagnosis of intellectual<br />

disability. The diagnosis is established by a pedagogical-psychological<br />

counselling centre or<br />

by a specialized pedagogical centre. The Inspectorate<br />

observed that in many cases the head teacher<br />

decided on a child’s placement in a special<br />

school without presenting such diagnosis. This is<br />

a very serious failure because the head teacher is<br />

the decision-making state authority and should<br />

be held responsible <strong>for</strong> such a situation.<br />

Equal access to education still beyond<br />

horizon<br />

Among children who are educated according<br />

to lower standards, the Roma children are the<br />

majority. The situation is the same concerning<br />

the number of diagnoses made by pedagogical<br />

counselling centres. Let us not pretend that the<br />

results are accidental. In a democratic country<br />

it is out of bounds to accept a thesis that claims<br />

that the number of intellectually disabled individuals<br />

is considerably higher in one ethnic group<br />

than in another. The core of the problem is more<br />

likely to be found in the selection of tests used<br />

Continued on page 4.<br />

3

4<br />

you decide!<br />

Jennifer Clark, author is a law student at Albany<br />

Law School, New York<br />

education as a fundamental<br />

human<br />

right vs. exclusion<br />

of disabled children<br />

Education is the vehicle <strong>for</strong> which children<br />

learn and establish the skills necessary<br />

to develop and grow. Education is<br />

also the foundation from which social interactions<br />

and self-empowerment stem.<br />

And despite education being critical to<br />

proper development, children with disabilities<br />

continue to face discrimination in<br />

the educational setting.<br />

The United Nations Convention on the Rights<br />

of Persons with Disabilities, which came into<br />

<strong>for</strong>ce in 2008, was drafted as a supplement to<br />

the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in an<br />

eff ort to protect individuals with disabilities. To<br />

date, there are 146 signatories to the Convention<br />

and 90 ratifi cations. The Convention recognizes<br />

that the term “disability” is evolving but notes<br />

that it typically includes individuals with longterm<br />

physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory<br />

impairments.<br />

There is estimated to be more than 650 million<br />

Continued from page 3.<br />

by the counselling centres, in the lack of quality<br />

personnel in the centres but also in the lack of<br />

motivation on the part of elementary schools<br />

to educate the Roma. This year the Inspectorate<br />

presented these observations to the Public Defender<br />

of Rights to decide whether or not this<br />

was a case of discrimination of the Roma. Three<br />

years after the Strasb<strong>our</strong>g verdict the ombudsman<br />

again confi rmed that unlawful activities<br />

still go on in the Czech education system, that<br />

we still discriminate against the young Roma.<br />

Is there anything positive we can say by way of<br />

in the world living with disabilities and many<br />

encounter obstacles which prevent them from<br />

receiving an education similar those who do not<br />

have a disability. Research has showed that people<br />

with disabilities are more likely to be poor<br />

and as such, they lack access to educational<br />

services. Statistics demonstrate that 19 per cent<br />

of less educated people have disabilities and<br />

11 per cent of better educated individuals have<br />

disabilities.<br />

In lieu of the Convention and ratifi cation by 90<br />

state parties, many countries have also implemented<br />

their own disability discrimination acts.<br />

The need to enact legislation is clear: 90 percent<br />

of children with disabilities in developing<br />

countries do not attend school. In the United<br />

Kingdom <strong>for</strong> example, the Disability Discrimination<br />

Act prohibits discrimination in schools<br />

and requires public entities to promote equal<br />

opportunities <strong>for</strong> individuals with disabilities.<br />

Some of the equal opportunities include access<br />

to public transportation and facilities and other<br />

educational services.<br />

In Scotland, the Disability Discrimination Act<br />

makes it unlawful <strong>for</strong> a school to discriminate<br />

against disabled individuals. The Act applies<br />

to all schools, not just state-funded schools.<br />

The obligations imposed on schools, however,<br />

do not apply to teaching aids and services.<br />

Instead, the Act applies to policies and procedures<br />

which may keep children with disabilities<br />

separate from those who do not have them.<br />

Compensation <strong>for</strong> claims of discrimination is not<br />

permissible in Scotland.<br />

conclusion? I hardly think so. Unlike last autumn,<br />

nowadays the question of inclusion has no political<br />

support. The Czech Republic still does not<br />

fulfi l its legal obligations, and there<strong>for</strong>e it would<br />

come as no surprise if there were more suits,<br />

guilty verdicts and penalties. The only surprise<br />

could be whether the action is brought by a<br />

Roma pupil or by a physically disabled child. But<br />

what worries me more is the fact that wrongfully<br />

segregated children still cannot go back to<br />

elementary schools. Another very distressing<br />

fact is that the Roma children are still excessively<br />

The United States has very detailed regulations<br />

ensuring those with disabilities are treated fairly<br />

and have equal educational opportunities. The<br />

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act was<br />

passed in 1975 and prior to its passage, at least<br />

one million children with disabilities in the United<br />

States were denied public education. The<br />

Act specifi cally addressed the educational needs<br />

of children with disabilities from birth to age 21.<br />

The Act requires that education-related services<br />

are designed to meet the unique learning needs<br />

of eligible children and schools are also required<br />

to create an individualized education program<br />

<strong>for</strong> each student. The Act also requires adequate<br />

services be provided, including transportation<br />

to and from school, speech-language pathology,<br />

psychological services, physical therapy, and<br />

recreation.<br />

<strong>Schools</strong> throughout the world are moving towards<br />

more inclusive environments which support<br />

children with disabilities. Many policies now<br />

prohibit authorities from denying children with<br />

disabilities admittance to school. Other regulations<br />

prohibit school authorities from allowing<br />

children with disabilities access to services and<br />

benefi ts off ered to students without disabilities.<br />

Despite the changes being made, many children<br />

are still discriminated against once they arrive at<br />

school. It is imperative that those with disabilities<br />

have the same opportunities to excel as those<br />

who do not have a disability, especially since<br />

education is recognized as a fundamental right.<br />

Education as a fundamental right vs. exclusion of<br />

children with disabilities: You decide.<br />

s<strong>our</strong>ce: www.isifa.com<br />

placed in <strong>for</strong>mer special schools, which further<br />

widens the social gap existing in Czech society.<br />

And it is clear that if we do not provide the Roma<br />

children with a chance to get better education,<br />

they will hardly learn self-reliance and independence<br />

from state assistance. Moreover, the<br />

current state of aff airs is exceedingly expensive<br />

<strong>for</strong> the State and it unnecessarily heightens<br />

social tension.<br />

The author is a close collaborator of the League of<br />

Human Rights

Michaela Tetřevová, lawyer of the League of Human<br />

Rights<br />

how does the system<br />

of threatened<br />

children care fail?<br />

the story of a family and their three-year struggle<br />

to get their children back in their care<br />

The Czech Republic has long been criticized<br />

by international organizations<br />

<strong>for</strong> the high number of children living<br />

in state institutions. More than 21,000<br />

children spend their childhood in such<br />

institutions. This number means that we<br />

are one of the leading countries with regard<br />

to the number of institutionalized<br />

children.<br />

<strong>What</strong> are the causes of this desperate<br />

state? The State fails mainly in providing<br />

preventive help to threatened families.<br />

Instead of helping parents in crisis, the<br />

State chooses to punish them by taking<br />

their children away. <strong>Children</strong> are often<br />

taken away from their parents with surprising<br />

rapidity. Getting them back can<br />

prove an extremely long and arduous<br />

task.<br />

Mr and Mrs Stejskal know all about this. Their<br />

two little daughters have been living in a state<br />

institution <strong>for</strong> two years now. The social services<br />

workers took them away after one night when<br />

the girls were left home alone. When they could<br />

not fi nd their mother, they went out on a balcony<br />

and called her. A municipal police patrol<br />

who happened to pass by noticed the crying<br />

children and notifi ed the child protection authority.<br />

The negligent parents were punished<br />

immediately. The next day the Stejskals were<br />

visited by a social services worker who took<br />

the children away. For a couple of months the<br />

girls were living with their grandmother and<br />

were seeing their parents regularly. Then, it got<br />

diffi cult <strong>for</strong> the grandmother to take care of two<br />

little children so they went to a state institution.<br />

The institution where the girls are living now is<br />

about 55 miles away from their parents’ home.<br />

Of c<strong>our</strong>se, there are state institutions which<br />

would be closer. But all of them were full at<br />

the time the girls’ placement was decided. No<br />

wonder, if we consider how many children live<br />

in state institutions! The considerable distance<br />

that separates the Stejskals from their daughters<br />

disrupts the family relationships. Both parents<br />

work full time in three-shift operation, so<br />

they are unable to see their daughters regularly.<br />

<strong>Children</strong> suff er in state institutions but<br />

c<strong>our</strong>ts are at ease<br />

The litigation concerning the institutionalization<br />

of the girls has been going on <strong>for</strong> three<br />

years and a decision is not going to be reached<br />

soon. To make things worse, education at a state<br />

institution begins to negatively aff ect the girls.<br />

The seven-year old Michaela is very friendly to<br />

everybody, and if somebody told her to come<br />

home with them, she would not hesitate. In<br />

contrast, younger Pavlína, who has been living<br />

in the state institution since the age of two and<br />

can remember nothing but the state institution,<br />

is distrustful and resentful.<br />

Several studies have already proved that children<br />

who are brought up in state institutions<br />

are more likely to have growth disorder, and<br />

have behavi<strong>our</strong>al disorders and low social and<br />

intellectual skills. Only one in 171 children<br />

growing up in a state institution gets a university<br />

degree. Other research shows that 56 per<br />

cent of children, who leave the state institution<br />

after they turn 18, commit a criminal off ence.<br />

But it seems that in case of the Stejskal family,<br />

the c<strong>our</strong>t does not take into consideration the<br />

negative aspects of state care. Instead of acting<br />

quickly and in the best interest of the child,<br />

it is not unusual that time periods separating<br />

the c<strong>our</strong>t proceedings go up to two months. It<br />

looks like time goes slowly in a c<strong>our</strong>t building,<br />

whereas with small children, just like Michaela<br />

and Pavlína, time fl ies fast.<br />

The Stejskals have been litigating a claim to get<br />

their children back <strong>for</strong> 1,088 days now. It is their<br />

bad luck that the c<strong>our</strong>t proceedings have been<br />

brought in the Northern Bohemia Region. These<br />

c<strong>our</strong>ts are well-known <strong>for</strong> their slow proceedings<br />

concerning the care of minors. In 18 per<br />

cent of cases the proceedings last <strong>for</strong> 6 months<br />

to 1 year. In 20 per cent of cases the proceedings<br />

go on <strong>for</strong> 1 to 3 years, which is the highest number<br />

in the Czech Republic.<br />

But the situation in other regions is no better.<br />

Long c<strong>our</strong>t proceedings represent a problem<br />

within the whole system. The Civil Procedure<br />

Code, which deals with proceedings concerning<br />

care of minors, un<strong>for</strong>tunately does not defi ne<br />

any period within which the c<strong>our</strong>ts should reach<br />

a decision. There only exist a 24-h<strong>our</strong> period<br />

<strong>for</strong> issuing a preliminary measure that places<br />

children in state institutions. But the preliminary<br />

measure is to be used in an emergency, in<br />

cases where the children are ill-treated, sexually<br />

abused or left with no one to look after them,<br />

and there<strong>for</strong>e it is necessary to act quickly. Un<strong>for</strong>tunately,<br />

in practice, the preliminary measure<br />

is often misused in cases of long-term family<br />

troubles.<br />

case<br />

Social services workers inspect and threaten<br />

but do not help<br />

This was the case of the Stejskals as well. The<br />

department of social services opened a fi le on<br />

Michaela and Pavlína in 2004. This was when<br />

problems fi rst occurred in the family. Mr Stejskal<br />

liked to have a drink in a pub and his wife used<br />

to go and pay his bills, when he drank more that<br />

he could pay <strong>for</strong>. When Mrs Stejskal used to go<br />

and pay her husband’s bill, the kids were left<br />

home alone. But Mrs Stejskal too liked to drink<br />

a little sometimes. One time, after she had been<br />

celebrating with a friend, she went to see her<br />

friend off and she shut herself out of doors. The<br />

eighteen-month-old Michaela was left home<br />

alone and fi re fi ghters had to help Mrs Stejskal<br />

open the apartment door again.<br />

So the Stejskals were visited by a social services<br />

worker several times. However, her visit always<br />

included a mere <strong>for</strong>mal inspection. In fifteen<br />

minutes she ran through the apartment, checked<br />

whether the fridge contained enough food,<br />

whether the clothes were nicely tidied in closets,<br />

whether the fl oor was well swept and whether<br />

the children were appropriately dressed.<br />

Then she simply in<strong>for</strong>med the parents that they<br />

should improve the education of their children<br />

and threatened to take the kids away. That was<br />

the end of any further communication with the<br />

family. The Stejskals never learned what they<br />

should improve in particular, and when.<br />

On the contrary, in the Netherlands and the United<br />

Kingdom it is common that if a family gets<br />

into trouble, a social services worker will call a<br />

family conference, at which the wider family<br />

gathers. Together they try to come up with an<br />

individual plan, which would comprise particular<br />

measures and tasks and a time schedule<br />

to go according to. The duties resulting from<br />

the individual plan, which has been drawn up<br />

by the whole family, are easily understandable<br />

<strong>for</strong> everybody and are not seen as an inimical<br />

intervention in family life. This contributes to a<br />

higher motivation of the family <strong>for</strong> keeping to<br />

the proposed plan. Moreover, the family eff ort<br />

is supported by a continuous evaluation, when<br />

the family and the worker discuss the measures<br />

that were successfully adopted and those that<br />

need to be yet taken.<br />

Continued on page 7.<br />

5

6<br />

interview<br />

questions <strong>for</strong>…<br />

…Josef <strong>Do</strong>beš, the Minister of Education<br />

How do you think an ideal school <strong>for</strong> y<strong>our</strong> children<br />

should look like?<br />

Above all, it would be a friendly environment<br />

created by teachers, parents and children. It<br />

would be a school where children could be freely<br />

educated without being manipulated. And<br />

at the same time it would be a safe place where<br />

children could explore all their possibilities.<br />

Candidates <strong>for</strong> the “Fair School” Award<br />

are better and better<br />

In the past month LIGA teachers visited new<br />

schools, which aim to be awarded the Fair School<br />

Certifi cate. They travelled the whole country<br />

and returned home satisfi ed. “I was pleasantly<br />

surprised by the high level of application of inclusive<br />

principles at schools. Most schools try to<br />

put into practice the philosophy and principles of<br />

equal access to education,” says Monika Tannenbergerová.<br />

At present, fi fteen schools from all<br />

over the Czech Republic have applied <strong>for</strong> the<br />

Certifi cate and applications still keep coming.<br />

Our pedagogical-legal team explains to the<br />

schools what they can expect and clarifi es any<br />

possible ambiguities. Throughout the year we<br />

counsel the schools engaged in the project and<br />

we watch how the inclusion goes at the schools.<br />

Whether the Certificate is awarded or not is<br />

decided by an independent board of experts.<br />

LIGA awards the Fair School Certifi cate to those<br />

schools that promote a fair approach to all pupils<br />

regardless of their handicap, special skills or<br />

skin col<strong>our</strong>. Since 2009 ten schools were awarded<br />

the Certifi cate and other schools joined the<br />

project this year.<br />

<strong>What</strong> do you think about inclusive education as a<br />

system? <strong>What</strong>, in y<strong>our</strong> opinion, is the signifi cance<br />

of the process of inclusion <strong>for</strong> society?<br />

Inclusion or integration of handicapped children<br />

is a completely proper process, it is necessary<br />

that this process take place in an entirely<br />

transparent way and that inclusion become an<br />

open dialogue between experts, representatives<br />

of regions and schools, and parents.<br />

<strong>Do</strong> you think that Czech special and practical<br />

elementary schools are really attended only by<br />

children who belong there?<br />

It would be naive to think that it is so. I will only<br />

confi rm the numbers, which I do not consider to<br />

be exaggerated, that 26 per cent of the children,<br />

who attend these schools, do not have any intellectual<br />

disability. It is a wrong approach. On<br />

the other hand, I fully support special schools,<br />

because they work in fairly diffi cult conditions<br />

and without appropriate acknowledgement<br />

and support.<br />

<strong>What</strong> is y<strong>our</strong> opinion of the D. H. verdict, and<br />

what solution would you propose, as a solution<br />

is inevitable according to the Strasb<strong>our</strong>g recommendation?<br />

The substance of the D. H. verdict is that children<br />

without intellectual disability should not<br />

be placed outside mainstream education. This is<br />

a matter to be considered and solved by Regulations<br />

No. 72 and 73, which need to be amended.<br />

<strong>We</strong> can achieve this by the end of January 2011.<br />

<strong>We</strong> achieved a signifi cant decision: Parents<br />

do not have to pay fines <strong>for</strong> not<br />

having their child vaccinated<br />

Parents who decide not to have their children<br />

vaccinated or to postpone the vaccination, can<br />

no longer be fi ned. This was the decision of the<br />

Supreme Administrative C<strong>our</strong>t, which accepted<br />

the arguments of LIGA that the Regulation on<br />

vaccination against infectious diseases is in<br />

contradiction with constitutional law. This puts<br />

an end to an often insensitive practice of health<br />

offi cials who imposed fi nes of up to 20,000 CZK<br />

on parents who refused to get their children<br />

vaccinated or to postpone the vaccination, even<br />

in cases the parents’ decision was based on the<br />

child’s bad reaction to a previous vaccination.<br />

“If the State wishes to en<strong>for</strong>ce this duty, this would<br />

have to be regulated by law,” says Josef Vlašín, a<br />

judge at the Supreme Administrative C<strong>our</strong>t.<br />

The ground-breaking verdict has been reached<br />

in the case of the Čechs who refused vaccination<br />

and were ordered by the Offi ce of Public Health<br />

to pay a fi ne of 8,000 CZK. Mr and Mrs Čech<br />

decided to defend themselves in c<strong>our</strong>t with the<br />

help of LIGA lawyers. After two years, success<br />

finally came and it can positively influence<br />

other similar litigations. The rights of patients to<br />

decide whether to get vaccinations or not has<br />

<strong>What</strong> will the progress of the National Action<br />

Plan on Inclusive Education be now that some of<br />

the experts, who collaborated on its drafting and<br />

realization, have left?<br />

It has to be said that the so-called NAPIV (National<br />

Action Plan on Inclusive Education) was<br />

prepared only in March <strong>2010</strong>. It took a very long<br />

time be<strong>for</strong>e the plan was created, the people<br />

engaged in the plan met once (June <strong>2010</strong>) and<br />

then somebody leaves. In my opinion, this is<br />

a short-term matter and I rather appreciate<br />

long-term projects. I will call NAPIV at the end of<br />

November <strong>2010</strong> and will gladly invite anybody<br />

who wants to continue with the project. I wish<br />

it were mostly perseverant and determined<br />

people.<br />

<strong>Do</strong> you think that education towards tolerance<br />

and removal of xenophobia and racism is suffi cient<br />

at schools?<br />

Generally speaking, it is necessary to put more<br />

eff ort in this matter, and not only at schools but<br />

also in families, sports fi elds (see sports stadiums).<br />

<strong>We</strong> can undoubtedly observe a certain<br />

progress and openness regarding this <strong>issue</strong>.<br />

Progress is achieved with regard to the attitude<br />

of the repressive organs, where a significant<br />

shift has been noted, because this environment<br />

is far less tolerant. But it is necessary not to stop<br />

focusing on this <strong>issue</strong> because it still represents<br />

a great danger <strong>for</strong> society.<br />

in short<br />

been a long-term <strong>issue</strong> <strong>for</strong> LIGA. “<strong>We</strong> think that<br />

the current legislation does not respect human<br />

rights. This repressive system is uncommon in all<br />

<strong>We</strong>stern countries,” says Zuzana Candigliota, a<br />

LIGA lawyer.<br />

Human Rights Clinic working again<br />

With the beginning of the new academic<br />

year LIGA introduced another c<strong>our</strong>se entitled<br />

Human Rights Clinic offered in cooperation<br />

with the Faculty of Law of Palacký University<br />

in Olomouc, with which LIGA cooperates on a<br />

long-term basis. David Zahumenský, the LIGA<br />

Chair, advised the students how to conduct an<br />

interview with a client. He also gave them some<br />

essential facts about health law. Within a threeh<strong>our</strong><br />

session the students had the opportunity<br />

to apply the acquired knowledge and skills in<br />

practice.<br />

The goal of the clinic is to use interactive methods<br />

to introduce students to the <strong>issue</strong> of<br />

human rights and their legal protection. At the<br />

same time the c<strong>our</strong>se aims to give the students<br />

practical legal skills and inspire them with a<br />

sense of professional responsibility towards<br />

disadvantaged social groups and public interest<br />

protection.

Are you a teacher, head teacher, education<br />

expert, parent of a handicapped child<br />

or just someone who cares? Our test will<br />

show you what legislative obstacles are<br />

in the way of education of disadvantaged<br />

pupils.<br />

questions<br />

1. Can a school refuse a pupil because they do<br />

not belong to the school neighb<strong>our</strong>hood?<br />

2. Can a Roma child be placed in a special or<br />

practical school only on the basis of their<br />

problematic behavi<strong>our</strong>?<br />

3. Can a school get a fi nancial contribution <strong>for</strong> a<br />

socially disadvantaged pupil?<br />

4. <strong>Do</strong>es the education legislation prefer group<br />

integration to individual integration?<br />

5. <strong>Do</strong>es a pupil with a mild intellectual disability<br />

have to attend a special school?<br />

6. Can a child be repeatedly kept in the same<br />

grade at elementary school?<br />

7. <strong>Do</strong>es the legislation include the concept of a<br />

“Roma assistant”?<br />

Continued from page 5.<br />

Solutions exist but only theoretically<br />

The concept of family conferences is far from<br />

being introduced here. A similar concept is suggested<br />

in the National Action Plan to trans<strong>for</strong>m<br />

and unite the system of care of threatened children<br />

but its realization is extremely uncertain.<br />

Although things seem to be changing at the<br />

Ministry, all plans exist only on paper and it may<br />

take years be<strong>for</strong>e they are put into practice. So<br />

<strong>for</strong> the time being, we stick to the usual practice,<br />

where the child protection authority keeps<br />

waiting until the situation in the family is bad<br />

enough <strong>for</strong> the children to be taken away upon<br />

correct answers<br />

1. NO. Only in case the school is at full capacity.<br />

The head teacher is obligated to primarily<br />

accept those pupils who live in the school<br />

neighb<strong>our</strong>hood. But if the school capacity is<br />

not filled with neighb<strong>our</strong>hood pupils, the<br />

head teacher cannot refuse a pupil from a<br />

diff erent neighb<strong>our</strong>hood.<br />

2. NO. A child can be placed in a special school<br />

only on the basis of a psychological expert<br />

opinion <strong>issue</strong>d by a counselling centre,<br />

which reveals that the child has special<br />

educational needs. Another necessary<br />

condition is the in<strong>for</strong>med consent of the<br />

child’s parent.<br />

3. NO. According to Regulation No. 492/2005 Coll.,<br />

test<br />

does Czech legislation keep<br />

disadvantaged children in mind?<br />

a c<strong>our</strong>t decision. In the defence of social services<br />

workers we have to admit that there is a lack<br />

of personnel. A Ministry report says that 560<br />

social workers are missing in the system. In the<br />

present situation, where one social worker has<br />

to deal with 354 cases of threatened children a<br />

year, it is impossible to think that the work with<br />

families will be perfect.<br />

But these facts cannot be used as an excuse. By<br />

the ratifi cation of the Convention on the Rights<br />

of the Child, the State has committed to promote<br />

the best interests of the child and has to<br />

do its utmost to do so. But <strong>for</strong> now the system<br />

is rather leaky.<br />

on Regional Norms a financial contribution<br />

can only be given to disabled pupils.<br />

4. NO. Individual integration is preferred.<br />

5. NO. It is preferred that the child be placed in<br />

a standard elementary school with an individualized<br />

education program, so they can<br />

attend a standard class.<br />

6. NO. A pupil can fail a class only twice during<br />

their studies at an elementary school.<br />

7. NO. A Roma assistant is a popular name used<br />

by general public. But the Education Act only<br />

knows the concept of “pedagogical<br />

assistant” who can be assigned by the head<br />

teacher to a class attended by a pupil with<br />

special educational needs.<br />

A more responsible approach to care <strong>for</strong> threatened<br />

children would surely be welcomed by<br />

the Stejskal children, who have been waiting in<br />

a state institution <strong>for</strong> two years <strong>for</strong> the c<strong>our</strong>t to<br />

reach a fi nal decision.<br />

7

8<br />

we published<br />

A documentary entitled “Fair <strong>Schools</strong>”<br />

See <strong>for</strong> y<strong>our</strong>selves that coeducation of all<br />

children works.<br />

In cooperation with professionals we have made<br />

a documentary about inclusive education, that<br />

is about the education of physically or socially<br />

disadvantaged or otherwise diff erent children<br />

in standard schools and classes. Although inclusion<br />

is a common and successful education<br />

system adopted abroad, in the Czech Republic<br />

it is still met with prejudices. That is why we<br />

have decided to publicly present three Czech<br />

schools that started applying the inclusion principles<br />

and successfully integrated pupils with<br />

physical or mild intellectual disabilities, autistic<br />

children, Roma children but also exceptionally<br />

gifted children who need special pedagogical<br />

assistance as well.<br />

The fi lm will present three children and their<br />

parents, teachers and classmates. <strong>We</strong> will show<br />

liga’s people<br />

LIGA’S PEOPLE LIGA’s People Club<br />

LIGA’S PEOPLE is a<br />

group of <strong>our</strong> regular<br />

contributors who<br />

help us protect human<br />

rights and improve<br />

the quality of<br />

life of all people in the<br />

Czech Republic.<br />

JOIN US AND YOU CAN GET<br />

• regular in<strong>for</strong>mation about <strong>our</strong> activities<br />

• <strong>EXTRA</strong> League Papers twice a year<br />

• invitations to social events and public discussions<br />

• annual report<br />

• new publications and other little gifts <strong>for</strong> free<br />

If you would like to support us, please contact<br />

Petr Jeřábek on 776 234 446 or send an email to<br />

lidiligy@llp.cz.<br />

www.lidiligy.cz<br />

<strong>EXTRA</strong> League<br />

Papers are fi nancially<br />

supported by the<br />

American Embassy in<br />

Prague.<br />

you how they live, how they study and how they<br />

do at schools awarded LIGA‘s Fair School Certifi -<br />

cate <strong>for</strong> their approach. The fi lm is intended not<br />

only <strong>for</strong> head teachers and teachers but also <strong>for</strong><br />

the general public.<br />

The grand premiere will take place on 3rd December<br />

<strong>2010</strong> on the occasion of the International<br />

Day of Persons with Disabilities.<br />

How to become a fair school II<br />

Inclusive education in practice<br />

The “How to become a fair school” manual<br />

has another volume. It is primarily intended<br />

<strong>for</strong> head teachers and teachers at elementary<br />

schools. You can fi nd there inspiring texts on<br />

inclusive education written by fair schools head<br />

teachers themselves. It also contains many interesting<br />

tips on classes and lessons. To help you<br />

orientate y<strong>our</strong>selves in this <strong>issue</strong> we have provided<br />

explanation of the most important terms<br />

and answers to frequently asked questions of<br />

teachers and pupils. Apart from this, you can<br />

learn about new features prepared by the Ministry<br />

of Education, Youth and Sports in the fi eld<br />

of legislation concerning children with special<br />

educational needs.<br />

CHEERING FOR JUSTICE!<br />

The rights of children are one of <strong>our</strong> major<br />

priorities here at the League of Human Rights.<br />

<strong>We</strong> think that if we do not help children get<br />

quality education and grow up in a family environment,<br />

we will probably sentence them<br />

to a life on the edge of the society. Thanks to<br />

y<strong>our</strong> support we can better en<strong>for</strong>ce the rights<br />

of children in practice.<br />

David Zahumenský, Chair<br />

WE WOULD LIKE TO THANK<br />

ALL DONOURS FOR THEIR HELP.<br />

IT PAYS OFF NOT TO BE INDIFFERENT.<br />

The League of Human Rights is<br />

supported by:<br />

The “How to become a fair school II” manual is<br />

available at www.llp.cz <strong>for</strong> free download.<br />

How to fairly compensate patients?<br />

Video <strong>for</strong> experts and others<br />

To familiarize the general public with the <strong>issue</strong><br />

of compensation <strong>for</strong> accidental damage in health<br />

care we have made a short documentary entitled<br />

“How to fairly compensate patients?” <strong>We</strong><br />

have used the example of an action brought by<br />

the bereaved family of the late Mrs Pechoušová<br />

to show you how diffi cult it is to orientate oneself<br />

in the Czech legislation concerning similar<br />

cases.<br />

Marie Cilínková, an attorney, will talk about her<br />

<strong>for</strong>ty years of experience with the defence of patients’<br />

rights. Gerald Bachinger, the head of the<br />

Patientenanwalt in Lower Austria, will explain<br />

how the Austrian system of compensations<br />

works. And LIGA will present their suggestions<br />

and recommendations on how to systematically<br />

solve the <strong>issue</strong> of patients’ compensation.<br />

You can watch the video at the LIGA’s YouTube<br />

channel.<br />

Imprint<br />

<strong>EXTRA</strong> LEAGUE PAPERS<br />

Issue 3, December <strong>2010</strong><br />

Issued by: The League of Human Rights,<br />

Burešova 6, 602 00 Brno,<br />

Registration No.: 26600315.<br />

Register of Ministry of Culture,<br />

Czech Republic: E 19103.<br />

Issued twice a year in Brno.<br />

Editor: Magda Kucharičová<br />

Graphics and typography:<br />

Nikola Spratek Poláčková<br />

www.nikolapolackova.com<br />

Title page picture: Aleš Čuma<br />

Contact: The League of Human Rights, Burešova<br />

6, 602 00 Brno, tel.: +420 545 210 446,<br />

fax: +420 545 240 012, email: brno@llp.cz,<br />

www.llp.cz,<br />

www.ferovanemocnice.cz,<br />

www.ferovaskola.cz,<br />

www.lidiligy.cz,<br />

www.re<strong>for</strong>maopatrovnictvi.cz.