100 People Who - Rosalind Franklin University

100 People Who - Rosalind Franklin University

100 People Who - Rosalind Franklin University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

“To serve the nation through the interprofessional education of<br />

health and biomedical professionals and the discovery of knowledge<br />

dedicated to improving the health of its people.”<br />

— rfums mission statement<br />

Judith R. Masterson

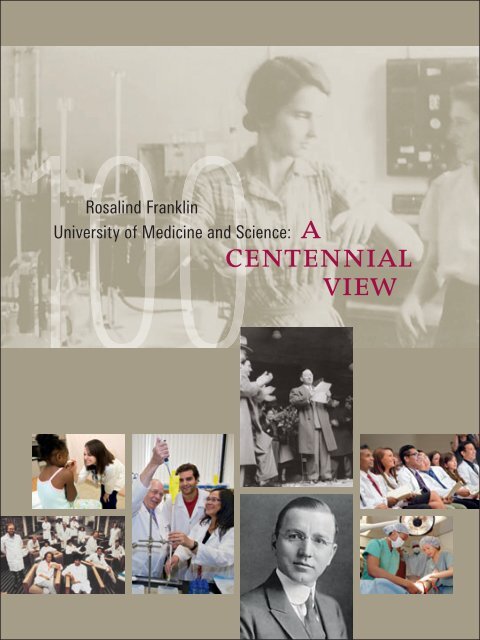

<strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> <strong>University</strong> of Medicine and Science: A Centennial View<br />

was published in celebration of the <strong>University</strong>’s <strong>100</strong>th anniversary.<br />

Copyright ©2012 <strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> <strong>University</strong> of Medicine and Science.<br />

All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced<br />

in any form without prior, written consent of rfums.<br />

published by<br />

<strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> <strong>University</strong> of Medicine and Science<br />

Division of Institutional Advancement<br />

3333 Green Bay Road<br />

North Chicago, IL 60064<br />

www.rosalindfranklin.edu<br />

produced by The Coventry Group, Chicago<br />

design and typography by Bockos Design, Inc., Chicago<br />

color separations by Prographics, Rockford, Illinois<br />

printed by Original Smith Printing, Bloomington, Illinois<br />

note to the reader<br />

The following acronyms are used in this publication:<br />

Chicago Medical School (cms)<br />

College of Health Professions (chp)<br />

College of Pharmacy (cop)<br />

Dr. William M. Scholl College of Podiatric Medicine (scpm)<br />

<strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> <strong>University</strong> Health System (rfuhs)<br />

<strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> <strong>University</strong> of Medicine and Science (rfums)<br />

School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (sgps)<br />

School of Related Health Sciences (srhs)<br />

<strong>University</strong> of Health Sciences/Chicago Medical School (uhs/cms)<br />

INTRODUCTION 06<br />

Celebrating Our History 07<br />

Chicago Medical School 16<br />

Dr. William M. Scholl College of Podiatric Medicine 19<br />

<strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> (1920 –1958) 22<br />

Pioneering Research 25<br />

Strategic Partnerships 29<br />

From Chicago to North Chicago 31<br />

A Commitment to Service 33<br />

The <strong>People</strong> of RFUMS 36<br />

A Bold Vision for Interprofessional Leadership 41<br />

RFUMS TIMELINE 46

06 | RFUMS<br />

introduction<br />

<strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> <strong>University</strong> of Medicine and Science<br />

celebrates <strong>100</strong> years of growth and transformation in the pursuit of its mission<br />

to prepare today’s medical and health care students to deliver the highest<br />

standard of health care in the future. This publication celebrates that history<br />

in the broadest sense.<br />

The <strong>University</strong> and its five colleges/schools —<br />

Chicago Medical School, College of Health Professions,<br />

College of Pharmacy, Dr. William M. Scholl College<br />

of Podiatric Medicine and the School of Graduate and<br />

Postdoctoral Studies — look forward to the future with<br />

confidence. Grounded in its collective strength, rooted<br />

in its historic past, today’s university is building on<br />

the progress of preceding generations that sought to<br />

offer the highest standard of medical and health care<br />

education. Proudly recognizing a century of service,<br />

the independent, nonprofit university salutes more than<br />

17,000 alumni who have devoted their professional lives<br />

to the health of others and who recognize that the license<br />

to practice is both a gift and a great responsibility.<br />

Our Heritage<br />

The Chicago Hospital-College of Medicine was founded in January 1912<br />

by three men who believed that the privilege of practicing medicine<br />

should not only accrue to the affluent. Two physicians and a minister —<br />

Dr. N. Odeon Bourque, Dr. Frederic Leusman and Reverend Frederick<br />

Landwer — were determined to open the profession to men and women<br />

of diverse backgrounds who found it necessary to work for their living.<br />

This was at the height of the Progressive Era, a reaction to industrialization<br />

that brought social reforms and struggles for the advancement of women,<br />

the working class and people of color. The same year of 1912, along with<br />

five physicians, a pharmacist, a chiropodist, a chemist and a shoe fitter,<br />

Dr. William M. Scholl founded the Illinois College of Chiropody and<br />

Orthopedics, also an open, egalitarian institution. Both institutions<br />

rejected the ethnic and racial quotas implemented by other schools and<br />

colleges at the time.<br />

In 1919 the Chicago Hospital-College of Medicine became the Chicago<br />

Medical School and fought for three decades to earn national accreditation.<br />

Its dogged pursuit of that goal made it stronger and drove administrative<br />

and curricular reforms, elevated leadership and elicited the talents of<br />

faculty, alumni and students alike who would take the fight for survival<br />

to both the General Assembly<br />

in Springfield and the halls of<br />

Congress in Washington, D.C.<br />

The original Chicago Medical School campus<br />

at 3830–3834 S. Rhodes Ave., Chicago.<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 07

08 | RFUMS<br />

CMS also had thrown open its doors to refugee physicians and scien-<br />

tific researchers from Europe when war was declared in 1939. The School’s<br />

founding principle of nondiscrimination helped to drive growth and garner<br />

financial support. In 1945, the School had added a new amendment to its<br />

constitution, declaring “admittance based solely on academic accomplishment<br />

and character merit without discrimination as to race, religion, sex or national<br />

origin.” First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt lauded the academic excellence and<br />

moral courage of CMS in her nationally syndicated “My Day” column.<br />

In 1948, led by the gifted anatomist John J. Sheinin, MD, PhD, DSc,<br />

CMS would become the first and only privately funded independent medical<br />

school among 79 unapproved institutions in the nation to survive the mass<br />

winnowing of American medical schools and thereby land on the cusp<br />

of a new, more expansive vision for health care brought on by the 1910<br />

Flexner Report. As Dr. Sheinin declared, “The Chicago Medical School is<br />

as American as the very Constitution of this country.”<br />

Meanwhile, at the Illinois College of Chiropody and Orthopedics,<br />

Dr. Scholl enlisted the help of highly respected chiropodist Alfred Joseph,<br />

founder of the emerging profession’s national association. Dr. Joseph raised<br />

the bar at the College, improving its curriculum, raising admissions<br />

requirements and abolishing a correspondence course. He also strengthened<br />

relations with the Chicago-area chiropody community. Reorganization<br />

brought top academic talent to the College, which changed its name in 1916<br />

to the Illinois College of Chiropody. As the profession of “podiatry,” a term<br />

that first came into use in 1917, continued to gain momentum, so did Scholl<br />

College, with its graduates establishing practices across the nation. Respected<br />

for their excellent clinical skill, many rose to prominence in national leadership<br />

within the profession. In 1938, the College helped lead a successful<br />

battle against a move to prohibit medical doctors from teaching in podiatric<br />

colleges, and its faculty and alumni helped gain parity for podiatrists in<br />

the nation’s military. The College would undergo a number of name changes,<br />

eventually becoming Dr. William M. Scholl College of Podiatric Medicine<br />

in 1981, honoring its primary founder and most faithful supporter.<br />

Surgery and observation room in the Illinois College of Podiatry, 1327 N. Clark St., Chicago.<br />

Through the ensuing decades, Scholl College alumni, who make up<br />

one-third of the nation’s podiatric physicians, have been instrumental<br />

in moving the profession forward.<br />

The evolution of both CMS and SCPM, their resilience and<br />

commitment to the development of new and better ways of teaching<br />

and learning, cannot be separated from the men and women recognized<br />

above who believed in both institutions and defended them. Such<br />

individuals drove achievement and embodied and bequeathed values<br />

including scholarship, teamwork and optimism. They made the<br />

institution what it is today.<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 09

10 | RFUMS<br />

Building on Our Heritage<br />

In 1963, Dr. John Sheinin, then President of the Chicago Medical School,<br />

called for the development of an independent university of health sciences<br />

where future medical professionals from varied disciplines would train<br />

together and learn to work in teams. Dr. A. Nichols Taylor, former President<br />

of UHS/CMS, also stressed an integrated educational model. Accordingly,<br />

the contemporary structure of today’s <strong>University</strong> began with the creation<br />

of a <strong>University</strong> of Health Sciences in 1967. CMS embarked on a bold new<br />

direction aimed at the training and education of students for a variety of<br />

health care professions. It was one of the first such universities in the country.<br />

Its components were the School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies,<br />

established in 1968, and the School of Related Health Sciences, established<br />

in 1970, now the College of Health Professions. With its integrated model<br />

for the education and training of an array of future health care professionals,<br />

the newly linked UHS/CMS heralded a slow, but seismic shift toward a more<br />

efficient, more collaborative system for the delivery of the nation’s health care.<br />

The <strong>University</strong> was renamed for its longtime Chair of the Board, Herman<br />

Finch, becoming Finch <strong>University</strong> of the Health Sciences/Chicago Medical<br />

School in 1993.<br />

Then UHS/CMS President Dr. A. Nichols Taylor and CMS Dean Dr. LeRoy Levitt<br />

speaking with Senators Edward Kennedy (center) and Robert Packwood (next to Kennedy)<br />

at a U.S. Senate health subcommittee hearing in Chicago, May 1971.<br />

In another daring decision, the <strong>University</strong> in 1974 undertook a move away<br />

from Chicago’s crowded West Side medical district to northern Lake County,<br />

where there was plenty of room to grow. It was beckoned by the North Chicago<br />

Veterans Affairs Medical Center, which offered an educational partnership,<br />

affiliation with the nearby Great Lakes Naval Hospital, buildable land and<br />

a multimillion-dollar, multiyear federal development grant. UHS/CMS was<br />

eager to improve patient care wherever it could, to expand clinical opportunities<br />

for its students and to advance the team-based, patient-centered health care of<br />

Students in the School of Related<br />

Health Sciences, 1976–1978.<br />

SCPM student Sonya Cates ’00 listening to<br />

a patient at a Peds and Pods community<br />

outreach screening, 1999.<br />

the future. The move north culminated in the construction<br />

of a $45 million academic building, dedicated in 1980.<br />

In 1982, the <strong>University</strong>, which always served area patients<br />

through free dispensaries and low-cost clinics, opened<br />

the Robert R. McCormick Clinic on the new campus.<br />

Today’s successor, the <strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

Health System, provides a range of medical services,<br />

offers free health screenings and meets the health care<br />

needs of RFUMS students.<br />

The Dr. William M. Scholl College of Podiatric<br />

Medicine merged with the <strong>University</strong> in 2001, when,<br />

as Chair of the Board of Trustees, former Dean Marshall<br />

Falk, MD ’56, helped to engineer this major addition<br />

to the <strong>University</strong> family. Scholl College bolstered the<br />

<strong>University</strong>’s faculty and programs. It moved its very<br />

active, student-staffed clinic to the campus, a boon for<br />

area patients who needed podiatric care. “It’s a symbiotic<br />

relationship,” said Daniel Bareither, PhD, Scholl College’s<br />

Senior Associate Dean of Educational Affairs and Professor<br />

of Basic Biomedical Sciences. “We added quite a bit when<br />

we merged, some really good long-range strategic planning<br />

among a number of abilities, and built on things already<br />

in place. The concept of interprofessional education was<br />

just starting to gain momentum within the <strong>University</strong><br />

and we became very much a part of that. We wanted to<br />

teach students how to work together for the common<br />

good, for patient-centered care.”<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 11

SCPM Associate Dean of Clinical Experiences<br />

and Associate Professor Dr. Karona Mason and<br />

SCPM students Benjamin Scherer ’10 and<br />

Molly Meier ’10 examining a patient in RFUHS’s<br />

Scholl Foot & Ankle Center, 2007–2008.<br />

12 | RFUMS<br />

The 2002 appointment of <strong>University</strong> President and CEO K. Michael Welch,<br />

brought renewed focus, energy and dynamism. A neurologist and former Vice<br />

Chancellor for Research and President of the Research Institute at the <strong>University</strong><br />

of Kansas Medical Center, Welch called for an institutional assessment that led<br />

to an administrative reorganization, financial transparency and a collaborative<br />

strategic planning process aimed at guiding the <strong>University</strong> through the<br />

21st century.<br />

Welch understood that despite the <strong>University</strong>’s rich<br />

history and many contributions to its community and the<br />

nation, it needed a more distinctive identity. The institution<br />

was renamed <strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> <strong>University</strong> of Medicine<br />

and Science, and as a reflection of its expanding vision of<br />

education, it declared a new dictum, “Life in Discovery.”<br />

The 2004 renaming signified a commitment, posed<br />

a challenge and offered inspiration. <strong>Franklin</strong>, a British<br />

chemist and researcher, whose meticulous research led to<br />

the discovery of the structure of DNA, like the <strong>University</strong><br />

and its member colleges/schools, confronted opposition,<br />

worked to meet and exceed the highest professional<br />

standards and persevered in the determination to harness<br />

hard science in the service of humanity.<br />

Carefully managed strategic growth has gained the<br />

<strong>University</strong> a reputation as an innovative leader in education<br />

that is transforming the delivery of patient-centered<br />

care, emphasizing interprofessionalism, evidence-based<br />

practice and quality improvement. At the forefront of the<br />

concept of the interprofessional health care team sits the<br />

College of Health Professions (CHP). Before national and<br />

international commissions and task forces began calling<br />

for health care educators to respond to the fallout of<br />

overspecialization — a shortage of primary care physicians,<br />

lack of accessibility and disparities in patient outcomes —<br />

CHP was modeling and teaching teamwork. “We have<br />

the opportunity to work with many different kinds of<br />

health professionals and to work in teams so comfortably<br />

because of this wonderfully diverse landscape of programs,”<br />

said Judith Stoecker, PT, PhD, CHP Vice Dean.<br />

“It gives us the opportunity to see the strengths of each type of practice.<br />

Each one brings the best of what they’ve learned to the patient care experience.<br />

We all bring something different that can provide the best health care in<br />

the world when we work together.”<br />

In 1970, CHP offered two baccalaureate programs — Physical Therapy and<br />

Medical Technology. The College is now home to seven different professional<br />

programs that confer 14 advanced degrees, enjoying the advantage of a built-in<br />

relational complexity. Today’s College boasts graduate programs for future<br />

physician assistants, pathologists’ assistants, physical therapists, nurse<br />

anesthetists, nutritionists, psychologists, clinical counselors, health care<br />

administrators and managers, and those who want to pursue interprofessional<br />

studies. The College has also taken the lead in online programming at RFUMS,<br />

for which it operates the only two fully online distance programs — Nutrition<br />

Education and Healthcare Administration and Management.<br />

CHP, which develops the interprofessional coursework taken by all<br />

first-year students in clinical programs, has earned the <strong>University</strong> national<br />

and international recognition. As a result, in 2011, the <strong>University</strong> dedicated<br />

the new, 23,000-square-foot, $5.5 million Morningstar Interprofessional<br />

Education Center (IPEC). The Center provides a modern setting for team<br />

learning, including spaces for small groups, clinical simulation suites and<br />

a case demonstration amphitheater. Every first-year student in a clinical<br />

program at the <strong>University</strong> takes a required interprofessional course to gain<br />

insight into and respect for different areas of expertise, and to learn to<br />

interact in teams, build those teams and lead them.<br />

RFUMS President and<br />

CEO Dr. K. Michael Welch<br />

and <strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong><br />

Jekowsky, niece of<br />

Dr. <strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> and<br />

RFUMS Trustee, speaking<br />

at the renaming ceremony,<br />

January 27, 2004.<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 13

14 | RFUMS<br />

In 2011, the <strong>University</strong> welcomed the inaugural class to its new College<br />

of Pharmacy, a key expansion of its academic health sciences programs, and<br />

one that has embraced our interprofessional environment. The new College,<br />

which accordingly is housed in the IPEC, offers a four-year curriculum that<br />

exposes students to diverse experiential learning opportunities at sites in<br />

community pharmacy, health care systems, private and public clinics and<br />

some of the nation’s foremost pharmaceutical companies. It also prepares<br />

them for modern pharmacy practice as vital members of the health care team.<br />

Gloria Meredith, PhD, COP founding Dean, Chief Academic Officer and<br />

Professor of Pharmaceutical Studies, said, “PharmDs (doctors of pharmacy)<br />

working on teams can help ensure patients use medications safely and reduce<br />

hospital readmissions.” Meredith cited Institute of Medicine data that shows<br />

that the United States has a comparatively high infant mortality rate and death<br />

rate due to medical errors. “If we can train our pharmacists, our physicians,<br />

our physical therapists and other health professionals to work in teams, the<br />

health care world as we know it will start to change.” Meredith said. ”When<br />

medical professionals work in teams, they improve the quality of care and<br />

in the process reduce costs.”<br />

Since the time it was first established in 1968, the School of Graduate<br />

and Postdoctoral Studies has continued to train graduate students and postdoctoral<br />

fellows for research careers in the biomedical sciences. “The Graduate<br />

School is both a focal point and source of innovation, discovery and progress,”<br />

said Joseph DiMario, PhD, SGPS Dean and Professor of Cell Biology and<br />

Anatomy. The School’s Interdisciplinary Graduate Program in Biomedical<br />

Sciences gives students who matriculate into SGPS the opportunity to sample<br />

and select the best fit among research options for their interests and career goals.<br />

SGPS also offers combined degree<br />

programs leading to MD/PhD and<br />

DPM/PhD degrees, allowing students,<br />

DiMario said, “to understand how to<br />

be a physician and a basic researcher<br />

at the same time.”<br />

COP founding Dean Dr. Gloria Meredith and<br />

the COP inaugural class cutting the ceremonial<br />

ribbon in the new Pharmacy Skills Laboratory,<br />

July 7, 2011.<br />

RFUMS, 3333 Green Bay Road, North Chicago, 2012.<br />

Research at the <strong>University</strong> has grown significantly since an investment<br />

in 2005 that recruited new basic science faculty/investigators, constructed<br />

new facilities and provided internal funding to sustain research. “We’ve seen<br />

reinvestment and reinvigoration of basic science research within the <strong>University</strong>,”<br />

DiMario continued.<br />

One hundred years after its inception, the <strong>University</strong> and its five member<br />

colleges/schools continue to meet the challenges of the nation’s health care<br />

needs. They continue to teach and to discover, holding to the highest standards<br />

of research and attracting top scientific investigators. They also continue<br />

an historic commitment to inclusion that goes beyond race, gender or ethnicity<br />

and embraces the expertise of all health care professionals. Its drive to seek<br />

advancement of its mission, its legacy of nondiscrimination, its dedication to<br />

the student body, and its courage in seeking and creating solutions to some of<br />

the nation’s most pressing health care concerns have made it a national leader<br />

in interprofessional health care education. “The <strong>University</strong>’s foresight and firm<br />

belief in the power of collaboration have made it open to adopting and adapting<br />

innovations like the transformative interprofessional model, to meet the health<br />

care needs of the future,” said <strong>University</strong> President and CEO Dr. K. Michael<br />

Welch. “Its commitment to this model for both education and practice prepares<br />

medical professionals who know they are not alone and understand how<br />

to work as an integral part of a collaborative health care team.”<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 15

Early Chemical Laboratory<br />

at Chicago Hospital-<br />

College of Medicine,<br />

3832–3834 S. Rhodes Ave.,<br />

Chicago, 1916.<br />

16 | RFUMS<br />

The Chicago Medical School’s fight to win accreditation<br />

highlights an institutional history rooted in the very qualities demanded<br />

of those who pursue the daunting path to becoming a physician: dedication,<br />

drive and determination.<br />

The School’s battle for survival began within a decade of its founding in<br />

1912. The Flexner Report, published in 1910 and aimed at improving the quality<br />

of medical services throughout the United States, called for stricter standards<br />

in medical education and a reduction in the number of medical colleges. The<br />

American Medical Association (AMA) quickly endorsed the report, creating the<br />

Council on Medical Education (CME) to administer a new system of inspections<br />

and ratings. The council strongly urged independent medical schools like CMS<br />

to become affiliated with major universities, establish endowments or close.<br />

Many medical schools<br />

succumbed. Nationwide, from 1906<br />

to 1929, their number dwindled<br />

from 161 to 79. In Illinois, where such<br />

schools were winnowed to five, CMS<br />

refused to fold. At every turn in<br />

a nearly three-decade battle, faculty,<br />

students, alumni and others who<br />

believed in the mission of CMS rallied<br />

to uphold and strengthen a school<br />

that, unlike its peer institutions,<br />

accepted students solely on merit<br />

and refused to set quotas based<br />

on religion or race.<br />

Then CMS Dean<br />

Dr. John Sheinin<br />

reading a proclamation<br />

announcing AMA<br />

accreditation of CMS,<br />

November 11, 1948.<br />

By the time John Sheinin,<br />

MD, PhD, DSc, the young chair of<br />

the School’s Department of Anatomy,<br />

was appointed Interim Dean in late<br />

1935, CMS had long since abolished<br />

its evening school curriculum, raised<br />

admission requirements and forged<br />

clinical affiliations with nearby<br />

hospitals, including Cook County<br />

Hospital. It had also restructured its<br />

board leadership. But despite those<br />

reforms, it was denied the credentials<br />

needed to send its graduates into the<br />

practice of medicine in most states.<br />

Dr. Sheinin, one of a raft of<br />

brilliant scientists and talented<br />

clinicians recruited by CMS during the Great Depression, became the lynchpin<br />

of a renewed effort to gain national accreditation. A Russian refugee who had<br />

fled the Bolshevik Revolution and narrowly escaped a firing squad in Poland<br />

after he was mistaken for a spy, Sheinin, an MD/PhD from Northwestern<br />

<strong>University</strong>, brought boundless energy and a singular focus to conquering the<br />

AMA’s resistance to CMS. His people skills proved an effective battering ram.<br />

He developed cordial relations with AMA officials, communicated with them<br />

frequently and sought their advice. He insisted that they provide a detailed<br />

list of their findings after each inspection. He then methodically corrected<br />

each deficiency.<br />

Dr. Sheinin oversaw a constitutional revision that outlined yet another<br />

reconstitution of the Board of Directors. He also made a convert of one of the<br />

School’s most fearsome critics, Reverend John C. Evans, the religion and education<br />

editor for the Chicago Tribune. Evans joined the CMS Board and connected<br />

Dr. Sheinin with Chicago’s philanthropic community, including prominent<br />

Jewish businessmen who were won over by the CMS policy of nondiscrimination.<br />

Railroad magnate Lester Selig, named Chair of the CMS Board in 1946, helped<br />

to engineer an affiliation with Mount Sinai Hospital and launch the Guarantee<br />

Fund, which ensured the School’s immediate financial future, lifting one of<br />

the final barriers to full accreditation.<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 17

CMS student Ngozi Nweze ’12 (right)<br />

celebrating the excitement of Match Day,<br />

March 16, 2012.<br />

Former CMS Dean Dr. Theodore Booden<br />

with CMS students.<br />

CMS student Lindsey Long ’11 and CMS<br />

Dean Dr. Russell Robertson at the Awards<br />

Ceremony, Navy Pier, June 2, 2011.<br />

18 | RFUMS<br />

The CME’s complete and total endorsement of CMS<br />

was announced at the annual convention of the Association<br />

of American Medical Colleges on November 9, 1948.<br />

Dr. Sheinin returned to an exultant student body two<br />

days later. The hard-fought, hard-won accreditation of<br />

the indomitable CMS marked the only such credentialing<br />

among 79 independent medical schools earmarked for<br />

closure by the AMA.<br />

Over the next six decades CMS experienced dramatic<br />

growth, making significant investments in research and<br />

facilities, forging new clinical affiliations and moving<br />

its campus to North Chicago in northern Lake County.<br />

The establishment in 1967 of the <strong>University</strong> of Health<br />

Sciences expanded the CMS curriculum and mission, and<br />

made it one of the first medical schools in the nation to<br />

develop integrated educational programs for both future<br />

physicians and health sciences professionals. Today CMS<br />

enrolls approximately 190 students per class; they pursue<br />

their degrees in a wide range of basic science and clinical<br />

science venues and learn to work as members of health<br />

care teams, a skill that lends a competitive advantage<br />

in health care settings of the future.<br />

When Dr. William M. Scholl College of Podiatric Medicine joined<br />

forces with <strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> <strong>University</strong> of Medicine and Science (then<br />

Finch <strong>University</strong> of Health Sciences/Chicago Medical School) in 2001,<br />

it was a marriage of two kindred and committed spirits. Both institutions<br />

were founded in Chicago in 1912. Both fought to survive. Both broke through<br />

barriers to meet and exceed the highest standards of medical education.<br />

Dr. Scholl was a man of indisputable drive,<br />

character and foresight. His conviction that the lower<br />

extremity, all but neglected by early medicine, was a<br />

vital part of overall health ignited the emerging field<br />

of podiatry and helped to transform it into a respected<br />

and highly valued discipline. Throughout his career,<br />

Dr. Scholl shepherded both his manufacturing business<br />

and the College and its accompanying foot clinics,<br />

providing direction and financial support. His pride<br />

in the podiatric profession, his generosity and support<br />

for it and his concern for both its practitioners and<br />

its patients never wavered. He pushed to advance the<br />

specialty and improve the College through a series of<br />

reorganizations, a move to larger quarters and, stronger<br />

curriculum and research. The College would ultimately<br />

undergo a number of name changes, taking the name<br />

of its founder and most ardent supporter in 1981.<br />

Dr. William M. Scholl (1882–1968).<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 19

The Illinois College of Chiropody commencement ceremony, Sherman Hotel, Chicago, 1923.<br />

20 | RFUMS<br />

Current SCPM Senior Associate Dean<br />

of Educational Affairs and Professor<br />

Dr. Daniel Bareither teaching at<br />

<strong>100</strong>1 N. Dearborn St., Chicago.<br />

Scholl College proved its mettle by surmounting<br />

a steady stream of challenges, many stemming from<br />

a resistant medical establishment. In 1938, the Chicago<br />

Medical Society prohibited members from teaching<br />

in podiatric medical schools. During World War II,<br />

Scholl students were denied deferment from the draft,<br />

and despite the fact that foot problems were the fourth<br />

largest cause of disability in the army, the military<br />

withheld commissions for podiatrists. After the war,<br />

Scholl College fought for recognition from the Veterans<br />

Administration so that its students could receive<br />

benefits under the GI Bill. The College also helped<br />

to lead the podiatric medical profession’s fight for<br />

insurance parity, inclusion in the Social Security<br />

Medicare program, clinical privileges at the nation’s<br />

hospitals and federal funding under the Health<br />

Professions Education Assistance Act.<br />

In the century since its inception, Scholl College, one of just nine<br />

podiatric medical schools in the country, has educated more than one-third<br />

of the nation’s podiatric physicians. “The College has been at the forefront<br />

of inspiring and leading change within the profession,” said current Scholl<br />

College Dean and alumna Nancy Parsley, DPM ’93, MHPE. “<strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> of Medicine and Science has fostered the College’s ability to be the<br />

leader in podiatric medical education through academic excellence, research<br />

and interprofessionalism. Coming to a health sciences university has had<br />

a huge impact on the College’s ability to truly prepare today’s students to<br />

be the leaders and providers of health care tomorrow.”<br />

SCPM Dean Nancy L. Parsley, DPM ’93, MHPE,<br />

accepting congratulations on her appointment,<br />

April 21, 2010.<br />

Associate Professor and current SCPM Associate Dean of Research<br />

and Director of CLEAR Dr. Stephanie Wu performing a procedure<br />

in the RFUHS Scholl Foot & Ankle Center, 2005.<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 21

22 | RFUMS<br />

<strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> in the laboratory.<br />

The story of <strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong>, the courageous British chemist whose<br />

vital role in the 1953 discovery of the structure of DNA has earned soaring,<br />

if belated accolades, is inspiring new generations of medical, research and<br />

health care professionals at her namesake university.<br />

<strong>Franklin</strong>, the quintessential scientist, who possessed a gift for experimentation<br />

and extraordinary devotion to the highest standards of research,<br />

earned a PhD in physical chemistry from Cambridge <strong>University</strong> in 1945.<br />

She excelled at the technique of crystallography, also called X-ray diffraction,<br />

a skill she perfected under the tutelage of top scientists in France. She applied<br />

that technique during World War II, studying the microstructures of carbon<br />

and coal, research that expanded new industrial uses for carbons. She also<br />

employed it in identifying the structure of certain plant viruses, including<br />

the tobacco mosaic virus. At the time of her death in 1958, <strong>Franklin</strong>, 37, was<br />

leading a research group and using X-ray diffraction in the study of the<br />

crippling polio virus.<br />

<strong>Franklin</strong>’s notoriety comes from a small window<br />

of her life, two years spent as a researcher at King’s<br />

College London. During the early 1950s, as international<br />

scientists, including Nobel Prize winner Linus Pauling,<br />

raced to discover the secret of life, <strong>Franklin</strong> struggled to<br />

prove to herself through mathematical equations what X-ray<br />

diffraction of DNA fibers appeared to suggest — a double spiral of<br />

nucleotides. She patiently labored to capture the famous Photo 51,<br />

a brilliant likeness of the B form of DNA, through more than <strong>100</strong> hours of<br />

X-ray exposure using a special camera and other equipment that she modified<br />

and assembled herself.<br />

The photo was fundamental to what would become the most significant<br />

biological breakthrough of the century — the discovery and description of<br />

the double helix structure of DNA, which earned <strong>Franklin</strong>’s fellow scientists<br />

Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Wilkins the 1962 Nobel Prize.<br />

While <strong>Franklin</strong> could not know for certain that Watson and Crick,<br />

who worked out of the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge, had used her<br />

unpublished data and remarkably lucid Photo 51 in unlocking the secret of<br />

how life is transmitted from cell to cell and generation to generation, she may<br />

have suspected it. But by the time<br />

Watson and Crick publicized their<br />

hypothesis on the double helix<br />

of DNA in the journal Nature on<br />

April 25, 1953 — an issue that also<br />

featured a paper by <strong>Franklin</strong> on<br />

her own findings, including her<br />

Photo 51 — she had turned her<br />

attention to viruses at Birkbeck<br />

College London.<br />

<strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> looking through<br />

the microscope.<br />

Photo 51. Nature,<br />

Volume 171: 740–41,<br />

©1953 Macmillan<br />

Publishers Ltd.<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 23

24 | RFUMS<br />

The prospect of discovery both beckoned and pushed <strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong>.<br />

The daughter of a prominent British family who embraced her Jewish identity<br />

and from an early age displayed a keen intellect, <strong>Franklin</strong> was a demanding<br />

and diligent scholar who refused to let the dangers and hardships of World<br />

War II interrupt her education. She pursued a career at the highest levels<br />

of research science during an era when gender discrimination was socially<br />

acceptable. She persevered through bouts of isolation and in less than collegial<br />

workplaces, and she fought for modest salary increases and titles commensurate<br />

with her responsibilities and stature.<br />

By the age of 30, <strong>Franklin</strong> was considered an international authority<br />

on carbons. She was in demand at international scientific conferences, where<br />

she was often the only woman presenter, and she was heavily published<br />

in prestigious scientific journals. American biochemist and contemporary<br />

Wendell Stanley described her as an “international courier of good will and<br />

scientific information.”<br />

Biographer Brenda Maddox conjectured that <strong>Franklin</strong> had come to the<br />

same realization as Albert Einstein, that “a scientist makes science ‘the pivot<br />

of his emotional life.’” Science may have been at the center of <strong>Franklin</strong>’s life,<br />

but she lived a full life outside of that milieu. She was a thoughtful and<br />

devoted friend, sister and daughter. She loved to travel and hike mountains,<br />

and she was a creative French cook.<br />

In 2004, <strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> <strong>University</strong> of Medicine and Science became<br />

the first medical institution in the United States to recognize a female scientist<br />

through an honorary namesake. In the renaming ceremony, President and<br />

CEO Dr. K. Michael Welch hailed <strong>Franklin</strong> as “a role model for our students,<br />

researchers, faculty and all aspiring scientists throughout the world.”<br />

The crystalline Photo 51, the rights to which were generously donated<br />

by Nature, was selected as the new logo, and “Life in Discovery” became<br />

the <strong>University</strong>’s motto.<br />

SGPS Dean and Professor<br />

Dr. Joseph DiMario<br />

with SGPS students<br />

Kristina Weimer (left) and<br />

Eric Cavanaugh (right),<br />

and Research Intern<br />

Tyler Buddel (center), in<br />

Dr. DiMario’s laboratory,<br />

June 2012.<br />

CMS research in<br />

a laboratory at<br />

710 S. Wolcott Ave.,<br />

Chicago.<br />

A university exists not to just teach knowledge, but to discover<br />

new knowledge.<br />

<strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> <strong>University</strong> of Medicine and Science trains outstanding<br />

research scientists who both benefit from and add to the <strong>University</strong>’s trailblazing<br />

commitment to interprofessional medical and health care education.<br />

“We continually strive to lead in our chosen fields of research,” said<br />

Joseph DiMario, PhD, Dean of the School of Graduate and Postdoctoral<br />

Studies, and Professor of Cell Biology and Anatomy. “The emphasis on interprofessionalism<br />

at RFUMS provides a truly unique, broad-based, interactive<br />

academic climate that contributes to our careers in biomedical sciences.”<br />

Teaching students how to conduct research, according to Ronald Kaplan,<br />

PhD, the <strong>University</strong>’s Vice President for Research and Vice Dean of Research<br />

for Chicago Medical School, provides them experience in the critical analysis<br />

of scientific literature across the health care spectrum, allowing them to make<br />

sound medical practice decisions. Scientific investigation can also generate<br />

passion. “It exposes students to the thrill of discovery and experimental<br />

success,” Dr. Kaplan said.<br />

The <strong>University</strong>’s history of scientific inquiry began<br />

in the early 1930s, as American medical schools placed<br />

a new emphasis on pre-clinical instruction in the basic<br />

sciences, as well as faculty research. CMS recruited<br />

prominent basic scientists as professors and invested<br />

in research laboratories and equipment. It welcomed<br />

foreign-born, research-oriented faculty who sought<br />

refuge from the rise of fascism across Europe.<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 25

Professor Dr. Charles<br />

McCormack and SGPS<br />

student Darlene Racker ’88<br />

in the laboratory, 1980s.<br />

Researchers at CMS in the 1940s and 1950s made seminal discoveries in<br />

the biological sciences, including the use of stereology in visualizing anatomical<br />

structures, and produced critical research regarding physiological hormones<br />

and the fundamental application of the enzyme horseradish peroxidase in<br />

labeling techniques. The School continued to expand its research focus and<br />

attract new generations of investigators in ensuing decades, among them<br />

outstanding cancer researchers whose work garnered substantial funding<br />

from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). In 1961,<br />

CMS completed construction of its Institute of Medical<br />

Research at 2020 West Ogden Avenue in Chicago. The<br />

facility, which would become home to the entire school<br />

in 1968, featured laboratories dedicated to oncology,<br />

experimental cardiology and biophysics. Today the<br />

<strong>University</strong>’s core areas of research include structural<br />

biology, neurosciences, specifically in the areas of<br />

addiction, and neurodegenerative disease, cystic fibrosis,<br />

viral oncology and cancer biology.<br />

The new millennium saw a major reinvestment in<br />

the <strong>University</strong>’s basic science departments with a capital<br />

infusion devoted to infrastructure, including 10 state-ofthe-art<br />

core molecular and sub-molecular laboratories and<br />

the hiring of 25 new basic scientists, recruited from top<br />

laboratories around the world, all of whom have obtained<br />

extramural funding and most of whom have gained NIH<br />

funds to support their research. “We’re very proud of the<br />

fact that our NIH funding over the last four to five years<br />

continues to increase despite the fact that NIH success<br />

rates have decreased significantly,” said Dr. Kaplan, also<br />

a CMS Professor of Biochemistry.<br />

<strong>University</strong> President and CEO Dr. K. Michael Welch<br />

said the Board and administration made a strategic decision<br />

to maintain and strengthen its basic science research.<br />

“We believe the <strong>University</strong> should not just use knowledge,<br />

but create it,” Dr. Welch said. “Providing opportunities<br />

for student research is an important part of their growth,<br />

giving them the competency to assess disease with the<br />

precision of a basic science hypothesis.”<br />

Students conducting psychology research.<br />

Professor Dr. Darryl Peterson (center),<br />

Research Assistant Elizabeth Green (left) and<br />

Postdoctoral Fellow Dr. Demetrios Zikos,<br />

1983–1984.<br />

26 | RFUMS<br />

Chair of the Department of Microbiology and<br />

Immunology and Professor Dr. Bala Chandran in<br />

the Heather Margaret Bligh Cancer Research<br />

Center with students, 2012.<br />

Then Professor and current COP Dean<br />

Dr. Gloria Meredith (right) and Associate<br />

Professor Dr. Judith Potashkin (left)<br />

conducting research, 2005–2006.<br />

RFUMS also sponsors several research<br />

institutes, including the Resuscitation Institute<br />

and Scholl College’s Center for Lower Extremity<br />

Ambulatory Research, or CLEAR, dedicated to<br />

improvements in the health and function of the<br />

lower extremities. “Very creative, very industrious<br />

scientists have put together these institutes and<br />

collaborate and interact with many other scientists<br />

across disciplines,” Dr. Kaplan said.<br />

Many student-oriented research programs,<br />

including the DPM/PhD degree program, emphasize<br />

multidisciplinary integration with the ultimate<br />

goal of providing better care and preventing<br />

disease. “By improving the health and function<br />

of the lower extremities, we help prevent falls in<br />

the elderly, mitigate lower extremity complications<br />

associated with diabetes, and create tools to assess<br />

and improve surgical outcomes,” said Stephanie<br />

C. S. Wu, DPM, MSc, Associate Dean of Research,<br />

Director of CLEAR and Associate Professor in<br />

Scholl College’s Department of Podiatric Surgery<br />

and Applied Biomechanics.<br />

Applying a sample for<br />

further purification are<br />

(left to right): Research<br />

Intern Nathaniel Saed;<br />

Research Associate<br />

Dr. Rusudan Kotaria; CMS<br />

Vice Dean for Research,<br />

RFUMS Vice President<br />

for Research and Professor<br />

Dr. Ronald Kaplan; Research<br />

Assistant Steven Stark<br />

and Research Laboratory<br />

Manager June A. Mayor<br />

in Dr. Kaplan’s Laboratory,<br />

July 2012.<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 27

28 | RFUMS<br />

Postdoctoral Fellows Dr. Sai Yalla<br />

and Dr. Gurtej Grewal in SCPM’s<br />

Center for Lower Extremity<br />

Ambulatory Research Human<br />

Performance Laboratory, 2012.<br />

CHP/Physician Assistant<br />

students Gina Roberts ’11,<br />

Heather Hackbarth ’11 and<br />

Crystin Robbins ’11 presenting<br />

at the All School Research<br />

Consortium, March 16, 2011.<br />

The <strong>University</strong> constantly seeks to promote and<br />

expand basic science, translational, educational and clinical<br />

research. It recently instituted an interdisciplinary pilot<br />

grant program requiring applications submitted by<br />

two co-principal investigators from different disciplines,<br />

departments or colleges/schools.<br />

“The way to succeed in a very difficult funding<br />

environment is to try to obtain synergy,” Kaplan said.<br />

“We’re bringing two separate sets of knowledge to bear on<br />

a project, bringing both approaches to create a synergistic<br />

outlook and initiate new kinds of research that will ultimately<br />

lead to new high-quality publications and additional<br />

extramural funding.”<br />

Another pilot grant program now underway aims<br />

to jumpstart more translational research in a carefully<br />

orchestrated collaboration between basic scientists from the<br />

<strong>University</strong> and clinicians from its primary teaching hospital,<br />

Advocate Lutheran General, with the current focus on<br />

cystic fibrosis, the use of stem cells in wound healing,<br />

traumatic injury, cancer and type 2 diabetes.<br />

The imminent future of research at the <strong>University</strong><br />

will include more collaborative research that will both feed<br />

off and foster the <strong>University</strong>’s interprofessional mission and<br />

that will prepare practitioners who will not only navigate,<br />

but also create the scientific advances of the future.<br />

“It’s a very exciting time,” Kaplan said. “The <strong>University</strong><br />

has invested tremendous resources in research. When you<br />

have bright, dedicated, committed people, it will pay off<br />

in a big way.”<br />

SCPM residency<br />

team at Cook County<br />

Hospital (left to right)<br />

Richard Pulla, DPM ’84,<br />

and residents Sheila<br />

Westmoreland, DPM ’91,<br />

Robert La Veau, DPM ’91,<br />

William Chubb, DPM ’91, and<br />

Tim Butler, DPM ’91, 1991.<br />

The many and varied teaching affiliations cultivated by <strong>Rosalind</strong><br />

<strong>Franklin</strong> <strong>University</strong> of Medicine and Science are a “special strength,” according<br />

to Dr. Russell Robertson, Dean, Chicago Medical School and Vice President<br />

for Medical Affairs.<br />

RFUMS students participate in community-based clinical rotations<br />

in both urban and suburban settings — experience that helps them gain the<br />

postgraduate opportunities they desire.<br />

“Our students are learning in extremely well-run settings where the<br />

quality of instruction is very high,” said Robertson. “I believe our students<br />

may get a stronger clinical education than may take place in academic medical<br />

centers which are often referral centers. They are seeing<br />

patients much earlier in the evolution of their health<br />

issues. They have the opportunity to think with greater<br />

originality.”<br />

The <strong>University</strong>’s first major clinical partnership<br />

was established in 1924 with Cook County Hospital.<br />

Nearly 90 years later, John H. Stroger, Jr. Hospital of<br />

Cook County is still a highly valued affiliate.<br />

CMS in 2011 designated Advocate Lutheran General<br />

in Park Ridge as its primary teaching hospital. The leading<br />

trainer of primary care physicians in Illinois, Advocate<br />

is an excellent fit. It is the only non-university hospital<br />

outside of Chicago that boasts physician residency<br />

programs in internal medicine, family practice, pathology,<br />

pediatrics, obstetrics/gynecology, orthopedics and<br />

psychiatry. It also offers fellowships in cardiovascular<br />

surgery, gastroenterology and geriatrics.<br />

SCPM affiliate Illinois Masonic Medical Center,<br />

Chicago, 1989.<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 29

CMS Class of 1960<br />

posing in front of<br />

Cook County Hospital,<br />

across the street<br />

from CMS, Chicago.<br />

“Through that relationship, we have department chairs in all major<br />

fields of medicine and that’s been very transformative,” said Robertson, who<br />

is also working to enhance collaboration with the Captain James A. Lovell<br />

Federal Health Care Center (LFHCC) in North Chicago and Mount Sinai<br />

Hospital in Chicago.<br />

From its inception in 1974, the affiliation with LFHCC, formerly the<br />

North Chicago Veterans Affairs Medical Center, has proven mutually beneficial,<br />

yielding higher quality of care, a broader range of medical services and faster<br />

treatment times for patients, attracting top academic and clinical talent under<br />

joint faculty appointments and providing expanded<br />

training opportunities for university students.<br />

Establishing its affiliation with CMS in 1947, Mount<br />

Sinai remains a key CMS partner because as a designated<br />

safety-net hospital it provides care to all regardless of ability<br />

to pay. It is also the clinical setting for CMS’ innovative<br />

Urban Primary Care Internal Medicine Residency program,<br />

which allows doctors to choose from three areas of concentration<br />

— community medicine, epidemiology/preventive<br />

medicine and women’s health.<br />

“At Mount Sinai and Cook County, our students<br />

see patients coming from all walks of life,” Robertson said.<br />

“It’s important for them to develop an acute awareness of<br />

the challenges faced by people from all demographics who<br />

are trying to meet their own health care needs.”<br />

RFUMS is also working with both the LFHCC<br />

and Advocate Lutheran General to develop more research<br />

collaborations that will lead to more funding from the<br />

National Institutes of Health and other funding agencies.<br />

“We value the relationship we have with the hospitals<br />

that do such a wonderful job of teaching our students,”<br />

Robertson said.<br />

The College of Health Professions, College of<br />

Pharmacy and Dr. William M. Scholl College of Podiatric<br />

Medicine each rely on numerous partnerships through<br />

which students report great satisfaction with clinical<br />

instruction. The <strong>University</strong> has made the engagement of<br />

high-quality academic and clinical partnerships, which<br />

advance its mission and support its interprofessional<br />

goals, a strategic priority.<br />

Mount Sinai Hospital, Chicago, 1949.<br />

Director of the Resuscitation Institute, Section Chief<br />

of Critical Care and Medicine, ICU Director and<br />

Professor Raul Gazmuri, MD, PhD ’94, and students at<br />

the Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care<br />

Center, North Chicago, 2010–2011.<br />

30 | RFUMS<br />

When the <strong>University</strong> of Health Sciences/Chicago Medical School pulled<br />

up stakes from its cramped 11-story building at 2020 West Ogden Avenue<br />

and left “the city of big shoulders,” it was a bold, but necessary move. It was<br />

also a gamble.<br />

The need for more room was evident by 1972, when the newly configured<br />

medical school and health sciences university, one of the first of its kind in the<br />

nation, was flooded with applications for admission. The new model demanded<br />

access to more clinical sites, leading the <strong>University</strong> to seek new vistas.<br />

Downey Veterans Administration Hospital in North Chicago was in<br />

search of a medical school affiliation. It offered UHS/CMS nearly <strong>100</strong> acres of<br />

unused land — and underutilized buildings to start out in — for a lease of one<br />

dollar per year. The move would be further funded with a seven-year federal<br />

grant — at $1.25 million per year — under the Health Manpower Training Act<br />

of 1972, designed to alleviate a serious shortage of health care professionals.<br />

State officials were eager to spread academic medical resources beyond Chicago<br />

to underserved parts of the state, and <strong>University</strong> Board Chair Herman Finch<br />

pushed for the acceptance of the VA’s offer.<br />

The decision to relocate to what some considered an outpost provoked<br />

immediate opposition. Several hundred of the <strong>University</strong>’s clinical faculty,<br />

affiliated with Mount Sinai Hospital, quit in protest. Students also rallied<br />

against the move. In Lake County,<br />

hospitals struggling in an economic<br />

recession warily eyed the newcomer,<br />

which they already considered<br />

a competitor. Resistance also came<br />

from a local health services planning<br />

council and the Illinois Veterans<br />

of Foreign Wars.<br />

Building 133 at former Downey VA Hospital, North Chicago, 1975.<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 31

Students learning in the laboratory, North Chicago.<br />

32 | RFUMS<br />

Prompted by these concerns, the <strong>University</strong> hired new faculty members<br />

who were stronger in research. It listened to its students, appointing leaders<br />

among them to decision-making committees. Finch and other administrators<br />

worked to develop new clinical affiliations and forge relationships in Lake<br />

County, where faculty and students also threw themselves into community<br />

service, staffing free clinics and otherwise expanding care to the underserved.<br />

By July 1974, an incremental move was underway,<br />

first among clinical faculty and then, two years later,<br />

by the UHS/CMS. In 1978, ground was broken for a new<br />

$45 million academic facility. The 300,000-square-foot<br />

building was dedicated on October 12, 1980.<br />

Current Chair and Professor of Pharmaceutical<br />

Sciences, Gary Oltmans, PhD, who joined the faculty<br />

in 1976, was attracted by the prospect of new education<br />

and research opportunities offered by state-of-the-art<br />

construction and partnership with a large clinical site.<br />

“We were able to expand our programs and move in a<br />

direction that contributed to the community, enhanced our<br />

research and added to the medical literature,” said Oltmans,<br />

who also recalled that the move gave the university<br />

community, previously shoehorned into a crowded medical<br />

district in the city, a fresh perspective and boost to morale.<br />

“It generated a lot of enthusiasm,” Oltmans said. “Energy<br />

was really high. Expanding the faculty and bringing in<br />

new chairs created a synergy that proved to be exciting<br />

and offered real opportunities. The move worked out<br />

phenomenally well.”<br />

RFUMS campus aerial view, 2005.<br />

UHS/CMS Groundbreaking, 3333 Green Bay Road, North Chicago, 1978.<br />

CMS obstetrics clerkship participants departing<br />

from the Chicago Maternity Center.<br />

SCPM’s award-winning Foot Care for the Homeless<br />

program providing care at a homeless shelter in Chicago,<br />

1987. Share Your Soles, a shoe donation program,<br />

also began in 1987.<br />

A health sciences university, by its nature, provides a service to<br />

its community. It educates and trains highly skilled and dedicated professionals<br />

who take on a sacred trust to relieve suffering, heal and put others first.<br />

The mission of <strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> <strong>University</strong> of Medicine and Science is rooted<br />

in the desire to improve the health of the nation and<br />

its people. From the beginning, the <strong>University</strong> enjoyed<br />

a mutually beneficial relationship with its neighboring<br />

communities. Patients received treatment at the <strong>University</strong>’s<br />

clinics, while students honed their clinical skills. Today<br />

both patients and students reap the benefits of treatment<br />

at the <strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> <strong>University</strong> Health System via<br />

the Scholl Foot & Ankle Center, Behavioral Health Center,<br />

Reproductive Medicine Center and other clinical sites.<br />

The RFUHS also operates a popular mobile health unit,<br />

Community Care Connection, which offers free health<br />

screenings, including blood pressure, blood sugar<br />

and cholesterol tests.<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 33

RFUMS President and CEO Dr. K. Michael<br />

Welch reviewing a model of the heart with<br />

CMS student Kristopher Wnek ’12 at the<br />

RFUMS Mini-Medical School, October 2008.<br />

Then SRHS Dean Dr. Cynthia Adams<br />

demonstrating a blood draw to a student<br />

phlebotomy team as part of a Lake County<br />

Urban League program, 1981–1982.<br />

34 | RFUMS<br />

Clinic at Illinois College of<br />

Chiropody and Orthopedics,<br />

1321 N. Clark St., Chicago, 1913.<br />

CHP Associate Dean, Associate Vice President for<br />

Academic Affairs and Professor Patrick Knott, PhD,<br />

PA-C ’96, said the <strong>University</strong>’s independence has helped<br />

forge a strong bond with its neighbors. “Historically, that’s<br />

the thing that makes us different,” Knott said. “Because<br />

we do not have a large university medical center in Lake<br />

County, we need to reach out to community health care<br />

providers, community hospitals, county government and<br />

other institutions as our clinical partners. These sites<br />

benefit as we use our faculty and students to promote and<br />

staff their events, and we benefit as our students participate<br />

in service learning. It’s a win-win situation that gives us<br />

a strong connection to our community.”<br />

Graduate medical and health sciences students have<br />

been a driving force for good. They aid in the operation<br />

and staffing of vital programs, including Health Care for<br />

the Homeless, New Life Volunteering Service, HealthReach<br />

Clinic and the International Health Interest Group. They<br />

volunteer for the annual Kids 1st Health Fair, which<br />

provides free school physicals, immunizations and dental<br />

and other health screenings to thousands of underserved<br />

Lake County children.<br />

According to Knott, students attracted to medical<br />

and health professions are very altruistic. “They want<br />

to help others and we make that a significant admissions<br />

requirement,” he said. “We look for students who don’t<br />

just say they want to help others, but who have really<br />

done it. We have to continue that opportunity, feed that<br />

propensity, while they’re here.”<br />

Robert Joseph, DPM ’03, PhD, said service-learning<br />

through the <strong>University</strong> provides “real life context and<br />

an element of empathy.” As a young podiatric medical<br />

student at Scholl College, Joseph witnessed an ER patient<br />

devastated upon learning that her foot required amputation<br />

due to complications of diabetes. Joseph, who was an<br />

Albert Schweitzer Fellow (the fellowship combats health<br />

disparities by developing leaders in service), piloted a<br />

grassroots effort to provide diabetic foot health education<br />

to residents of Chicago’s Chinatown neighborhood.<br />

CHP/Physician Assistant<br />

student Kristine Jennings ’09<br />

conducting a back-to-school<br />

physical at the Kids 1st<br />

Health Fair, August 5, 2009.<br />

Today Dr. Joseph serves as Chair and Assistant Professor of SCPM’s<br />

Department of Podiatric Medicine and Radiology. “Service-learning happens<br />

all the time here,” Joseph said. “Whether it’s through interprofessional<br />

courses, in the Scholl Clinic, or working on the RFUHS Community Care<br />

Connection, all provide a different type of interaction with different<br />

populations. Students gain an awareness and acumen that everybody’s<br />

unique, even if they have the same disease process.”<br />

Faculty, staff and alumni also volunteer countless<br />

hours in community outreach to hospitals, clinics,<br />

homeless shelters and schools throughout the region.<br />

The <strong>University</strong> collaborates with community partners to<br />

offer assistance in the development of community-based<br />

service projects and health-related services. “Students<br />

these days want a real life connection between what<br />

they’re learning and why they’re learning it,” Dr. Knott<br />

said. “To sit a group of students down and teach them<br />

anatomy and biochemistry and physiology in a vacuum<br />

doesn’t work. Service-learning experiences — like<br />

meeting and treating a patient with diabetes and seeing<br />

and hearing about their difficulties — make learning in<br />

the classroom much more meaningful.” Alumna Kristina<br />

Hoque, PhD ’09, said community service helped teach<br />

her how to live as a true medical professional. “The best<br />

doctors don’t just study or operate,” Hoque said. “They<br />

go out and experience every aspect of medicine from<br />

very different perspectives, cultures and viewpoints.”<br />

As part of the RFUMS student-run<br />

International Health Interest Group, CMS<br />

student Charles Nguyen ’11 working during<br />

a medical service trip to Subcentro de<br />

Salud Arajuno, Puyo, Ecuador, 2008.<br />

CHP/Physical Therapy student<br />

Paul Tuazon ’14 leading students from<br />

Forrestal Elementary School in an activity<br />

during the North Chicago Community<br />

Partners After School Program, 2011.<br />

COURTESY OF NORTH CHICAGO COMMUNITY PARTNERS.<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 35

Former<br />

Associate Professor<br />

Dr. Carolyn Thomas<br />

with CMS students<br />

Edward Blumen ’73 and<br />

Michael Gordon ’73 at<br />

2020 W. Ogden Ave.,<br />

Chicago, 1970.<br />

36 | RFUMS<br />

Students, faculty and alumni of <strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

of Medicine and Science stand on broad shoulders. In the fall of 1923,<br />

the fledgling Chicago Medical School was engaged in a battle for survival.<br />

The Illinois Department of Registration and Education (IDRE), unhappy with<br />

founder Dr. N. Odeon Bourque, withdrew recognition. A small group of<br />

second-year students rose to the challenge. These men — a vice consul for<br />

the Peruvian government, a state senator’s son and a practicing attorney —<br />

met with Illinois Governor Len Small, who arranged a meeting for the<br />

students with the IDRE. The agency demanded no less than the resignation<br />

of the School’s Board of Directors. The students found an ally in a faculty<br />

member who agreed to reason with the unconventional and idealistic<br />

Dr. Bourque, who soon resigned along with the rest of the board. New<br />

leadership stepped up and the crisis was averted. In 1931, the IDRE again<br />

threatened to close CMS. This time three young members<br />

of the faculty, including two of the men from the 1923<br />

committee — Abel Larrain, MD ’26, and H. Edmund<br />

Quinn, MD ’26 — met with the School’s president and<br />

negotiated reforms that saved it.<br />

Then Physical Therapy Instructor, and current Chair of the Department of<br />

Physical Therapy and Associate Professor Dr. Roberta Henderson (left),<br />

and then Associate Professor and Chair, and current CHP Dean and<br />

Vice President for Academic Affairs Dr. Wendy Rheault (right), explaining<br />

pain management, North Chicago, 1985–1986.<br />

CMS alumni with Dr. John J. Sheinin (center) at commencement, Chicago.<br />

Throughout the history of RFUMS, stakeholders have come forward to<br />

lead, bring change and pave new paths in perilous times. When the American<br />

Medical Association in 1941 recommended that CMS students be subject<br />

to the draft and graduates denied commissions, students, faculty and alumni<br />

descended on Washington, D.C., armed with evidence of the School’s competitive<br />

academic record, superior clinical facilities and distinguished faculty.<br />

This homegrown lobby was a resounding success.<br />

The strength and vision of the <strong>University</strong> is also rooted in its historic<br />

commitment to diversity. Its admissions policy, based solely on merit —<br />

a rejection of the quotas used by other schools to restrict Jewish enrollment<br />

and deny access to people of color — is as old as the School itself. Dubbed<br />

the American Plan in 1947 by CMS Dean Dr. John Sheinin, the policy helped<br />

draw leadership and financial support.<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 37

38 | RFUMS<br />

SRHS Department of<br />

Physical Therapy Chair<br />

Virginia Daniel, MS, RPT,<br />

welcoming students,<br />

September 1971.<br />

Equal opportunity was also a building block at Scholl College, which<br />

joined RFUMS in 2001 and, like other colleges/schools in the <strong>University</strong>,<br />

admitted students regardless of race or religion. Scholl alumni Alfreda<br />

Sluzewski, DPM ’37, and Milo Turnbo, DPM ’34, successfully battled<br />

discrimination by state and national professional associations. Theodore<br />

“Tedi” Clarke, DPM ’50, who was barred from membership in the Indiana<br />

Podiatry Association in the 1950s, became the first African American —<br />

the first member of any minority group — to serve as President of the<br />

American Podiatry Association, a post he accepted in 1978.<br />

“Our commitment today is as strong as ever to the recruitment of<br />

a diverse student body that has an extraordinary track record of service<br />

and academic achievement,” said Rebecca Durkin, Associate Vice President,<br />

Student Affairs and Enrollment Management. “Our students bring with<br />

them a fundamental drive toward leadership and community service,<br />

qualities that translate into more than 80 student organizations active<br />

in both the <strong>University</strong> and local communities.”<br />

Then Associate Professor, and current<br />

Vice President for Faculty Affairs and Professor<br />

Dr. Timothy Hansen (left) with preceptors<br />

and students participating in the Chicago<br />

Area Health and Medical Careers<br />

Program, 1983–1984.<br />

Faculty, students and staff work in myriad ways to support the <strong>University</strong>.<br />

At every turn, alumni have also been crucial in sustaining and expanding<br />

the mission of their alma mater through their leadership, financial gifts and<br />

volunteerism and by their commitment to the highest medical and ethical<br />

standards of both pedagogy and patient care. “<strong>People</strong> who want to be in the<br />

health care field, whether they’re students, faculty or staff, have a vision of<br />

service that is part of their being,” said Timothy Hansen, PhD, Vice President<br />

for Faculty Affairs and Professor of Physiology and Biophysics and Pharmaceutical<br />

Sciences. “It’s about their patients whether directly or indirectly,<br />

but it’s also about contributing to the greater good.”<br />

RFUMS and its five colleges/schools have collectively graduated more<br />

than 17,000 alumni who dedicate their professional lives to the health and wellbeing<br />

of their patients. Alumni hold leadership positions in national health care<br />

associations and serve as hospital administrators, private practitioners and<br />

health care advocates. They are recognized in their respective fields for<br />

excellence and dedication.<br />

COP Inaugural<br />

White Coat Ceremony<br />

in Rhoades Auditorium,<br />

September 9, 2011.<br />

CHP/Pathologists’ Assistant Department Director<br />

of Clinical Education and Assistant Professor Brandi<br />

Woodard, PA(ASCP) cm ’06, and Assistant Program<br />

Director and Instructor Lisa Dionisi, PA(ASCP) cm ’05,<br />

with Program Director, Acting Chair and Assistant<br />

Professor John Vitale, PA(ASCP) cm , working together<br />

in the John J. Sheinin MD, PhD, DSc, Gross Anatomy<br />

Laboratory, North Chicago, 2009–2010.<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 39

40 | RFUMS<br />

Faculty, staff and<br />

students who served<br />

on the RFUMS 2012–2015<br />

Strategic Planning<br />

Committee receiving<br />

acknowledgement during<br />

the Staff Recognition<br />

and Awards Ceremony,<br />

February 24, 2012.<br />

Leadership and service are hallmarks of RFUMS, an institution that<br />

from its inception beckoned people who would not be denied the opportunity<br />

they deserved. “<strong>People</strong> felt fiercely about that opportunity,” Hansen said.<br />

“They’ve been extremely loyal to this <strong>University</strong>. They’ve fought for it.”<br />

CMS alumna Lisa Gelman, MD ’08,<br />

giving a physical at the Kids 1st Health Fair,<br />

Waukegan, August 3, 2011.<br />

SCPM student Sallee Taylor ’15 providing nutrition<br />

information to children during a service learning project<br />

for the Interprofessional Teams and Culture in Health<br />

Care course, Lambs Farm, Libertyville, 2011.<br />

CMS student and<br />

Executive Student<br />

Council President<br />

Zubin Wala ’14<br />

speaking at the ribbon-<br />

cutting ceremony<br />

for the Morningstar<br />

Interprofessional<br />

Education Center,<br />

July 7, 2011.<br />

Interprofessionalism is promoted by the U.S. Department of Health<br />

and Human Services, the World Health Organization, the Institute of Medicine,<br />

the Association of American Medical Colleges and other groups that cite<br />

research indicating patient health and safety can be compromised when<br />

health care professionals do not communicate. <strong>Rosalind</strong> <strong>Franklin</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

of Medicine and Science has been a pioneer of interprofessional health sciences<br />

education in the nation, a model in which students in different disciplines<br />

learn from, with and about one another as a means of improving collaboration<br />

and quality of care.<br />

RFUMS has already become a national leader in this paradigm shift in<br />

the delivery of health care that is even now improving patient care and patient<br />

satisfaction, and addressing a growing shortage of primary care physicians.<br />

Graduates of the <strong>University</strong> are entering their professions with a new attitude,<br />

and a new skill: the willingness, expectation and ability to work in interprofessional<br />

health care teams. “We’re a small, nimble university. We don’t<br />

have a silo structure. We’re well positioned to do this,” said Wendy Rheault,<br />

College of Health Professions Dean and Vice President for Academic Affairs.<br />

“We’re training the leaders of the future who will go out and promulgate this<br />

educational model, and make a sea change in clinical practice.”<br />

<strong>100</strong> YEARS | 41

CHP/Clinical Laboratory Sciences students<br />

Julie Babarik ’10 (center) and Melissa Jones ’10 (right)<br />

demonstrating dental hygiene during a service<br />

learning project for the Interprofessional Teams and<br />

Culture in Health Care course, Lambs Farm,<br />

Libertyville, 2008.<br />

42 | RFUMS<br />

CHP Dean and Vice President for<br />

Academic Affairs Dr. Wendy Rheault<br />

(left) and CHP Vice Dean and Associate<br />

Professor Dr. Judith Stoecker (right),<br />