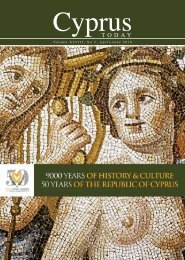

Cyprus Today, Jan-March 2007.pdf 1-27

Cyprus Today, Jan-March 2007.pdf 1-27

Cyprus Today, Jan-March 2007.pdf 1-27

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Editorial<br />

Nicosia, the capital of <strong>Cyprus</strong> is the place which has been continuously inhabited<br />

for the longest time on the whole island. It can boast an almost uninterrupted<br />

succession of settlements from the Chalcolithic period in the 4th millennium<br />

BC to the present day.<br />

Modern Nicosia is built on layers of ruins, the typical stratigraphy being - from<br />

the lowest strata - Cypro-Archaic, Hellenistic, Byzantine, Frankish, Venetian,<br />

Ottoman a long succession of civilizations. It is not surprising, therefore,<br />

that many construction sites in Nicosia may turn out to be archaeological areas<br />

the earth yielding up its secrets as archaeologists painstakingly work to uncover<br />

the mysteries it held back for centuries.<br />

After St George’s Hill, where the discovery of part of the ancient city has put<br />

the project for a new House of Representatives building on hold (see relevant<br />

article by Dr Despo Pilides in <strong>Cyprus</strong> <strong>Today</strong>, vol. XXXVII, April - June<br />

1999), and the unearthing of a Lusignan castle in the heart of the old city<br />

where a new municipal building is to be erected, a new surprise was in store<br />

on the construction site of the new Supreme Court. The site, situated on the<br />

eastern bank of the Pedieos River revealed the ruins of a 14th century convent<br />

of the Cistercian Order.<br />

In the main article of the present issue of our review, archaeologist, Eftychia<br />

Zachariou-Kaila, whose team have been carrying out intensive excavations,<br />

presents their important findings which do not only identify an important<br />

monastery but also provide clues to the lifestyle of nuns living in Cistercian<br />

convents.<br />

In the same revelatory and exploratory spirit, Dr Sophocles Hadjisavvas, in his<br />

article “Wine Culture in <strong>Cyprus</strong>” presents the case of wine making on the<br />

island through the eyes of an archaeologist. The topic was well debated throughout<br />

the centuries. Historians, geographers and travellers often refer to the wines<br />

of <strong>Cyprus</strong>, for which the island has been renowned since antiquity, as being<br />

‘extremely subtle’ or ‘exquisitely light’. Pliny considers <strong>Cyprus</strong> wine to be superior<br />

to all other wines, while Strabo designates <strong>Cyprus</strong> as ‘an island of fine<br />

wines’. Mediaeval travellers never fail to praise the strong and rich wine of<br />

<strong>Cyprus</strong>. Although the beginning of wine making in <strong>Cyprus</strong> cannot be dated<br />

with certainty, Dr Sophocles Hadjisavva’s article reveals archaeological evidence<br />

which suggests that wine making was practiced long before Pliny’s or Strabo’s<br />

references. It is obvious that the roots of viticulture in <strong>Cyprus</strong> go back to<br />

the depths of history as the roots of our vines to the depths of our land.<br />

1

2<br />

The Cistercian<br />

Convent<br />

of St. Theodore<br />

in Nicosia<br />

Rescue Excavation in the Supreme Court Area<br />

The medieval fortification of Nicosia,<br />

as it developed before the 16th century,<br />

was made redundant with the arrival of<br />

gunpowder, which changed century old<br />

traditions of warfare. Guns and fortresses<br />

were now essential for defence.<br />

Due to the pressure of Ottoman expansionism<br />

that appeared as early as the 15th<br />

century, the old medieval fortifications<br />

Nicosia within the Venetian walls<br />

Eftychia Zachariou Kaila - Department of Antiquities<br />

that protected the cities of the Venetian<br />

empire needed to be modernized. Consequently,<br />

in 1567 the Venetian Crown<br />

began designing the new walls of Nicosia.<br />

The Venetian walls of Nicosia had a smaller<br />

circumference than the previous Lusignian<br />

walls. In order to achieve a better<br />

defence system it was thought necessary<br />

to demolish any building that lay in the<br />

area between the old and new walls. The<br />

ruins of these buildings became valuable<br />

sources of sandstone, which was<br />

the main material used for facing the new<br />

walls.<br />

Among the eight churches – both Orthodox<br />

and Catholic – and the five monasteries<br />

that were sacrificed in the name<br />

of defence, was the female monastery dedicated<br />

to St. Theodore, which belonged<br />

to the Latin Cistercian Order (Estienne

de Lusignian, Description de toute l’isle<br />

de Chypre, Paris, 1580, fol.32).<br />

In his important book on the Gothic<br />

Art in <strong>Cyprus</strong>, published in 1899, the<br />

French archaeologist Camille Enlart mentions<br />

St. Theodore, which was already<br />

known from written sources, as being one<br />

of Nicosia’s vanished monasteries and<br />

whose exact location was unknown.<br />

More than a century later, on the construction<br />

site of the new building of the<br />

Supreme Court and covering the area of<br />

the new building’s future monumental<br />

entrance, chance finds were unearthed which<br />

identified the site as the remains of the nunnery<br />

of St. Theodore.<br />

On the 30th of August 2004 the contracting<br />

company of the new Supreme Court building<br />

notified the Department of Antiquities<br />

that a tombstone had been unearthed<br />

during construction work. It was therefore<br />

necessary to thoroughly examine the<br />

area.<br />

3

4<br />

The inscribed tombstone unearthed during the<br />

construction of the new Supreme Court. The figure<br />

of the abbess, Plaisance de Giblet, who died in<br />

1328, is engraved on it<br />

The inscribed tombstone, which happens<br />

to be our most important find, enables us<br />

to link the architectural finds with the available<br />

historical enidence1 . In this context the<br />

female figure engraved on the tombstone<br />

holds a staff in her left hand, which symbolizes<br />

both the abbess’s power and her pastoral<br />

role. The figure is bordered by an<br />

inscription, which refers to Plaisance de<br />

Giblet, abbess of the nunnery of St. Theodore,<br />

who died on Friday, 10th of February 1328.<br />

In 1244 the head of the Cistercian Order,<br />

Abbot Boniface of Citeaux (the original and<br />

leading monastery of the Cistercian Order)<br />

gave his approval for the foundation of an<br />

abbey of nuns of the Cistercian order in<br />

Nicosia. This was with the initiative of Alice<br />

of Montbeliard, widow of the regent Philip<br />

of Ibelin, who wished to provide a place for<br />

her daughter Mary. The plot for this convent<br />

was located between the first Dominican<br />

house and the location of the future<br />

Beaulieu Abbey, a Cistercian men’s monastery,<br />

which was then in the hands of the Franciscans.<br />

St. Theodore was not just the average Latin<br />

nunnery. The inscription on the tombstone<br />

demonstrates the significance of the abbey:<br />

not only was the founder a woman of a leading<br />

noble family and the widow of the regent<br />

of the Kingdom of <strong>Cyprus</strong>, but almost a<br />

century later its abbess, Plaisance, was a<br />

member one of the most important Cypriot<br />

noble families, the Giblets, who were<br />

among the highest nobility after the Lusignans<br />

and the Ibelins.<br />

The abbey was probably the richest nunnery<br />

of <strong>Cyprus</strong> as is shown from church tax<br />

records. The only monasteries to pay high-<br />

1 I would like to thank Chris Schabel, Assistant Professor of Medieval History at the University of<br />

<strong>Cyprus</strong> for his valuable contribution.

General view of the excavation site<br />

er taxes were the wealthy and powerful<br />

men’s abbeys of Cistercian Beaulieu, Premonstratensian<br />

Bellapais and Benedictine<br />

Stavrovouni.<br />

According to the Italian traveller Niccolo<br />

Martoni, by 1394 "St. Theodore, which is<br />

a church of nuns", was situated "within the<br />

walls of the city". This gives us another clue<br />

about the extent of the walls constructed<br />

5

6<br />

in the fourteenth century, which were replaced<br />

by the present Venetian walls in 1567. Until<br />

the 1360s, Nicosia appears to have been<br />

without walls.<br />

In his Italian Chorograffia of 1573, Etienne<br />

de Lusignan mentions that the Cistercian<br />

nuns of St. Theodore lived in the monastery<br />

until it was destroyed in 1567. Unfortunately<br />

the phrase is not in the later, corrected<br />

French translation, which suggests that St.<br />

Theodore did not survive upto 1567.<br />

The excavation, which began in the first<br />

week of September 2004, was carried out<br />

in collaboration with the archaeologists<br />

Efthymia Alphas, Stalo Eleftheriou and<br />

Xenia Michael.<br />

The area under excavation consisted of 800<br />

square meters, its limits being the Supreme<br />

The foundation of the lavabo unearthed<br />

Court building which was under construction<br />

in the north part of the site, the 1930s<br />

building known as the Poulias building in<br />

the south, and Charilaos Mouskos street in<br />

the east.<br />

Considering that by the time the Department<br />

of Archaeology was informed and<br />

arrived at the site the construction of this<br />

public building was approaching its completion<br />

and the contractors were desperately<br />

attempting to meet strict deadlines, one can<br />

appreciate how difficult the working conditions<br />

were. The excavation therefore took<br />

place quite literally in the middle of the construction<br />

site.<br />

Only a very small part of the monastic building<br />

complex has been revealed. The monastery’s<br />

very bad state of preservation and the absence

Efthymia Alphas and Stalo Eleftheriou excavating<br />

at the site<br />

of any architectural evidence beyond the<br />

wall foundations make the site’s reconstruction<br />

extremely difficult. We are however<br />

familiar with the perfectly preserved<br />

12th and 13th century Cistercian monasteries<br />

in France.<br />

Given that gothic architecture in <strong>Cyprus</strong>,<br />

although based upon western artistic styles,<br />

had its own particular character, it seems<br />

likely that the same was true for the architecture<br />

of St. Theodore’s monastery.<br />

The architecture of Cistercian monasteries<br />

follows strict conventions which reflect the<br />

Cistercian monastic way of life. Decorative<br />

sculpture is absent while representations<br />

and the use of colour is generally avoided.<br />

The nucleus of the monastic building complex<br />

is the cloistergarth which is usually rectangular<br />

or square in plan and is surrounded<br />

by four colonnaded galleries (quadriporticus).<br />

In the area covered by the staircase of<br />

the Supreme Court a cloister yard has been<br />

revealed, which is rectangular in plan and<br />

measures 22 by 18m, along with the galleries<br />

which surround the yard. Adjacent to<br />

the eastern wall of the yard the foundations<br />

of a lavabo have been unearthed. The lavabo<br />

is circular in plan and part of the drainage<br />

The Poulias building<br />

system consisting of a clay pipe has survived.<br />

Research on Cistercian monasteries in France<br />

has shown that there is evidence that the<br />

vaulted galleries that formed the cloister<br />

were not just passages but that they were<br />

also areas where religious processions took<br />

place during specific religious events and<br />

for the ceremony of the weekly washing<br />

of the feet (pedilavium) which was an enactment<br />

of Christ washing his disciples’ feet.<br />

As far as the monastery of Saint Theodore<br />

in Nicosia is concerned, the northeast<br />

corner of the galleries was probably the<br />

abbess’s burial ground. Unfortunately it is<br />

not possible to locate her tomb with certainty<br />

since the digger that revealed her<br />

tombstone caused much damage by removing<br />

important evidence.<br />

The vaulted galleries provided covered access<br />

to various rooms that opened onto them.<br />

The excavation also revealed a group of<br />

rooms in the south that open onto the south<br />

gallery. Although the function of these<br />

rooms has not yet been determined, the<br />

remains (kilns, unbaked clay) point towards<br />

the area being used as a workshop and a<br />

kitchen area. A large amount of cooking<br />

7

8<br />

ware was also noted from this area.<br />

At the westernmost part of these rooms, and<br />

bordering the Poulias building, two pits<br />

were excavated, providing valuable information<br />

since they contained sealed deposits.<br />

Both cooking ware and glazed pottery were<br />

unearthed from the first pit including a<br />

Majolika type jug that can be attributed<br />

to workshops in the Venice region.<br />

In addition, two vessels (Plain ware) with<br />

vertical handles were found but their use<br />

has not yet been determined.<br />

The second pit contained local pottery,<br />

which can be dated to between the end of<br />

the 15th and the beginning of the<br />

16th century.<br />

Among the above was also<br />

an open bowl, imported<br />

from Italy with both<br />

incised decoration and<br />

painted green and yellow<br />

motives.<br />

The excavations<br />

revealed the remains<br />

of at least 35 burials,<br />

covered by irregularly<br />

shaped stone slabs. In some cases river<br />

stones were used to delineate the graves.<br />

Most of the dead were positioned with their<br />

arms placed across their body below their<br />

chest whereas others were placed with<br />

their arms and wrists placed parallel to their<br />

bodies. Evidence of wooden coffins was not<br />

noted in any of the burials. Although the<br />

study of the graves has not yet begun it is<br />

expected that the human remains do not<br />

belong exclusively to the female members<br />

of the convent as it was a customary practice<br />

of the mediaeval church to offer prayers<br />

for the dead and space for family tombs in<br />

exchange for financial donations, as well<br />

as to the staff hired by the nuns for heavy<br />

manual work.

A collective analysis of the human bones<br />

from excavations of the mediaeval sites of<br />

Nicosia will perhaps provide valuable information<br />

concerning the population, the<br />

changes in standards of health and the diet<br />

of the city’s inhabitants during this period.<br />

A very basic preliminary study of the pottery<br />

and the coins unearthed shows that the<br />

site was continually inhabited between<br />

the 13th and the end of the 16th century,<br />

which agrees with the written sources that<br />

place the monastery’s founding and destruction<br />

within this time limit.<br />

The next period which is documented by<br />

the evidence is the end of the 19th century<br />

and the beginning of the 20th century,<br />

when the British built army premises in the<br />

area, which are still known today as the<br />

Wolsely Barracks.<br />

The Department of Antiquities, being the<br />

responsible body for the protection of antiquities,<br />

believed that the preservation and<br />

consequently the display and visibility of<br />

the site were issues that needed to be considered<br />

seriously and resolved.<br />

Even though the site’s preservation is fragmentary,<br />

the excavated features can be identified<br />

and can be historically positioned,<br />

providing valuable historical evidence but<br />

also acting as a landmark in the landscape<br />

of mediaeval Nicosia.<br />

Following the Department of Antiquities’<br />

demand to incorporate the antiquities<br />

into the new Supreme Court<br />

building plan, the plans<br />

regarding the access to the building needed<br />

to be altered. The initial plans included<br />

an access via a staircase on an embankment,<br />

which would have led to the building’s main<br />

entrance, whereas a second point of access<br />

would have led to the open space at the back<br />

of the building. Antiquities were unearthed<br />

in both access routes.<br />

The solution that was suggested by the Architect,<br />

Mr Alexandros Livadhas, and was<br />

approved by the Department of Antiquities,<br />

provided for the creation of an accessible<br />

archaeological site, which is covered<br />

by the main entrance’s 600 square meter<br />

elevated concrete slab, which is supported<br />

by 11 foundation supports. Natural light<br />

in this area is provided through openings<br />

made in the entrance’s concrete slab.<br />

The proposed solution also provided for the<br />

construction of a platform (in the south part<br />

of the site) covering a surface area of 200<br />

square meters and composed of horizontal<br />

glass slabs which cover the site and at the<br />

same time allow it to be visible. A special<br />

Various glazed pottery items found on the site<br />

9

10<br />

ly designed passageway leading to the exhibition<br />

area and to the building’s outdoor<br />

spaces was placed on top of these glass slabs.<br />

The planners made the positioning of the<br />

11 support columns after the Department<br />

of Antiquities made sure that the supports<br />

would not affect the archaeological features.<br />

Although the building of the new Supreme<br />

Court along with the salvage excavation that<br />

simultaneously took place is a small-scale<br />

project since the area of archaeological investigation<br />

was rather limited, it is however the<br />

first time that an attempt has been made to<br />

incorporate ancient remains in a modern<br />

public building in <strong>Cyprus</strong>.<br />

The Convent of St. Theodore in Nicosia<br />

was not the only Cistercian religious house<br />

in <strong>Cyprus</strong>. Written sources locate the existence<br />

of the monastery of Beaulieu at Pyrgos<br />

in the Limassol district. However its<br />

position has not to this day been sufficiently<br />

investigated archaeologically.<br />

After a short period the monastery moved<br />

from Pyrgos to the outskirts of the walled<br />

city of Nicosia. This monastery, known as<br />

Beau Lieu, was located in 1901 during exca-<br />

One of the 35<br />

tombs found during<br />

the excavations<br />

vations by the French archaeologist Camille<br />

Enlart. It was not identified as such, however,<br />

because Enlart considered that it was<br />

a Franciscan monastery, having been led to<br />

this conclusion by additions which were<br />

made at later stages. The site where Enlart<br />

carried out the excavation remains unknown<br />

to contemporary research because the architectural<br />

remains of the monastery are no<br />

longer visible, having been covered up or<br />

destroyed. The only known information for<br />

finding the position is the description which<br />

Enlart gives and which locates it to the west<br />

of the city, on the axis of Ayia Sophia and<br />

Panayia tis Tyrou.<br />

This axis runs exactly from the area between<br />

Kinyra, Korivou and Rimini Streets to a<br />

short distance from Paphos Gate and the<br />

new Supreme Court building. The area<br />

between the above streets has been acquired<br />

by the Republic of <strong>Cyprus</strong> for the purpose<br />

of building offices for the Town<br />

Planning and Housing Department.<br />

In September 2005 archaeological investigations<br />

began on the site, and are still in<br />

progress, in cooperation with the archaeologist<br />

Stalo Eleftheriou.

In the north section of the excavated site<br />

architectural remains have been found which<br />

although fragmentary relate to a building<br />

of monumental character. A large room was<br />

found, aligned east-west, 9 metres wide and<br />

about 25 metres long. The wall, 120 centimetres<br />

wide appears to extend to the east,<br />

beyond the excavated site. To the north of<br />

this room smaller walls have been uncovered<br />

which appear to have been extended<br />

to form smaller rooms belonging to the same<br />

complex. The walls made of limestone and<br />

river gravel were used for their foundations.<br />

The scientific documentation and the assessment<br />

of the various finds of the site will perhaps<br />

indicate a new determination of the<br />

position, as in the case of the site of the<br />

Supreme Court, providing us with important<br />

information about the topography of<br />

mediaeval Nicosia. It will be a link which<br />

will in the future possibly lead to the identification<br />

of other sites as well, such as those<br />

of the other monasteries mentioned in the<br />

sources, relating finally to the extent of<br />

the mediaeval fortifications of Nicosia which<br />

no longer survive.<br />

Bibliography:<br />

Annual Report of the Department of Antiquities for<br />

the year 2004, (Nicosia 2006), 86-90.<br />

N. Coureas, The Latin Church in <strong>Cyprus</strong>, 1195-1312,<br />

(Aldershot 1997).<br />

C. Enlart, Gothic Art and the Renaissance in<br />

<strong>Cyprus</strong>, trans. D. Hunt (London 1987).<br />

C. Enlart, “L’ ancient monastère des Franciscains à<br />

Nicosie de Chypre,” Florilegium Recueil des<br />

travaux d’ erudition dédiés à M. Le Marquis de Vogüé,<br />

(Paris 1909), 215-29.<br />

C. Schabel, O Camille Enlart Î·È ÔÈ ∫ÈÛÙÂÚÎÈ·ÓÔ›<br />

ÛÙÔÓ ‡ÚÁÔ, Report of the Department of Antiquities<br />

2002, 401-406.<br />

The Supreme Court entrance after the construction of the concrete slabs and before the glass slabs were placed<br />

11

12<br />

Wine Culture<br />

in <strong>Cyprus</strong><br />

The well-known House of Dionysos in<br />

Paphos illustrates in mosaic form the importance<br />

of the vine and wine in <strong>Cyprus</strong> during<br />

the Roman occupation of the island.<br />

The principal hall, the triclinium, is decorated<br />

with a carpet-like mosaic floor representing<br />

vintage scenes, vines laden<br />

with grapes and humans and erotes pick-<br />

Dr Sophocles Hadjisavvas<br />

ing the fruit. Apart from the many representations<br />

of the god of wine Dionysos,<br />

who gave his name to the house, the most<br />

prominent panel of the west portico which<br />

communicates with the triclinium depicts<br />

the history of winemaking. King Ikarios,<br />

unaware of Dionysos’ true identity gave<br />

the god hospitality while the latter was on<br />

Mosaic depicting Dyonisos with nymph Akme drinking wine from a bowl. Late 2 nd and early 3 rd century.<br />

Nea Paphos

Vintage mosaic, House of Dionysos, Nea<br />

Paphos. Hunting scenes, a rabbit pecking<br />

a bunch of grapes, birds and peacocks<br />

13

14<br />

a visit to Athens. Dionysos showed his gratitude<br />

by teaching Ikarios how to cultivate<br />

the vine and make wine from its fruit<br />

- something that up until then was unknown<br />

to mortals.<br />

The mosaic depicts King Ikarios returning<br />

home with a cart loaded with wineskins.<br />

On his way he met two shepherds to whom<br />

he gave some wine to taste. The shepherds<br />

became intoxicated and are shown falling<br />

down. An inscription in Greek above them<br />

explains why: "those who drank wine for<br />

the first time". This tragic episode is the<br />

mythological assumption that winemaking<br />

is a divine present to the mortals.<br />

Winemaking was known in <strong>Cyprus</strong> long<br />

before Strabo wrote his Geography and<br />

even longer before the Paphos mosaic was<br />

made. I will try to present the case of winemaking<br />

on the island of Aphrodite through<br />

the eyes of an archaeologist, starting with<br />

the cultivation of the vine.<br />

Macrobotanical remains attesting to the<br />

presence of vines on the island were found<br />

in two Neolithic and in almost all Chalcolithic<br />

sites from all over <strong>Cyprus</strong>. Thus,<br />

the earliest archaeological proven evidence<br />

dates back to the middle of the fifth millennium<br />

BC. Pip imprints were discovered<br />

in two sites of the Early and Middle Bronze<br />

Age as well as in later Late Bronze Age sites.<br />

The particular shape and size of the pips<br />

enabled archaeobotanists to distinguish<br />

between the wild grapevine and the cultivated<br />

Vitis vinifera. Thus while the earlier<br />

specimen is of uncertain identification<br />

because of its incomplete nature, the later<br />

specimen may be classified as belonging<br />

to a cultivated species of vine.<br />

It is quite possible that the wild species<br />

Vitis sylvestris existed on the island long<br />

before its habitation along with the remaining<br />

"first fruits of civilization" such as<br />

Mosaic depicting King Ikarios and the first wine drinkers. Late 2nd – early 3rd century. Nea Paphos

the olive, the fig and dates. It is rather difficult<br />

to make any assumptions concerning<br />

the time and circumstances under which<br />

the wild vine was brought into cultivation.<br />

We may, however, suggest that the inten-<br />

Rock-cut installation used as a press<br />

sive cultivation of the grapevine led to specialization<br />

of labour.<br />

Another question which remains to be<br />

answered is the time of the first winemaking<br />

on the island. There is no direct evidence<br />

for the production of wine in ancient times.<br />

Archaeologists have not discovered large<br />

deposits of fruit which had been crushed<br />

for the extraction of juice to be drunk as<br />

wine after fermentation. There are, however,<br />

some installations related<br />

to wine production but<br />

their dating is obscure.<br />

To some extent these installations<br />

are similar<br />

or identical<br />

Clay model showing a<br />

ritual related with<br />

grape treading<br />

15

16<br />

to olive oil production installations. Whatever<br />

the case, much equipment related to<br />

wine production was made of wood,<br />

thus leaving no trace in the archaeological<br />

record. Indirect evidence for the consumption<br />

and most probably the pro-<br />

Head of Bacchus in relief. Limestone, 3rd century BC<br />

duction of wine is present in the form of<br />

wine residues found in the bottom of pointed<br />

amphoras suitable for transport and<br />

storage. A large number of them have been<br />

discovered in the Hellenistic layers of the<br />

House of Dionysos in Paphos.

Wine “eye” cup decorated with Dionysos. (Polis)<br />

Some idea about wine producing installations<br />

may be obtained from representa<br />

tions of everyday life scenes appearing on<br />

the shoulders of different types of vases<br />

dating to the Early and Middle Bronze<br />

Age. One such deep bowl of Red Polished<br />

Ware was found in Kalavasos<br />

and published in 1986. The bowl<br />

bears a scenic composition which<br />

it seems the excavator interpreted as a<br />

wine press scene. A fragmentary human<br />

figure to be standing in a trough and he/she<br />

may be crushing grapes. This interpretation<br />

is by no means certain. The bowl dates<br />

to the Middle Bronze Age (c. 1900 BC).<br />

A much better and more realistic scene<br />

appears on a richly decorated Red Polished<br />

ware jug discovered in a tomb in the village<br />

of Pyrghos two years ago. The jug is<br />

provided with a double cut-away neck and<br />

two vertical handles from rim to shoulder.<br />

A large number of everyday life scenes<br />

rendered in the round occupy the entire<br />

shoulder of the vase. The most notable<br />

are a ploughing scene, a woman<br />

holding an infant, women<br />

preparing bread, a donkey<br />

carrying goods and<br />

a prominent seated figure.<br />

The most complicated<br />

group represents<br />

several figures possibly<br />

treading grapes for the production<br />

of wine. A human figure, its extended<br />

hands supported by the two vertical<br />

handles of the jug, is standing<br />

within an oblong spouted trough. A receptacle<br />

circular basin is placed below the projecting<br />

spout to receive the treaded product.<br />

Another human figure is standing<br />

behind the receptacle basin, its hands holding<br />

a jug with cut-away spout in the basin.<br />

The whole arrangement of the human<br />

figures in combination with the placement<br />

of the treading trough and the receptacle<br />

basin hint to the presence of a wine press-<br />

Kantharoid bowl decorated with bunches of grapes<br />

17

18<br />

ing installation. The iconography of the<br />

<strong>Cyprus</strong> vase is almost identical to a vintage<br />

and treading scene from a painting in the<br />

Tomb of Nakht dated c. 1372-1350 BC<br />

from the Valley of the Nobles in Thebes.<br />

The Egyptian painting, however, shows<br />

three standing figures in the treading trough<br />

while the remaining features are identical<br />

to the Cypriot vase. Naturally a painting<br />

affords many more possibilities for detailed<br />

representation than modelling in clay. A<br />

similar scene is known from an Attic blackfigured<br />

amphora by the painter Amasis dated<br />

c. 550 BC, not to mention later representations<br />

in mosaics and other media.<br />

As I have mentioned before,<br />

wine producing installations<br />

are similar to olive<br />

oil installations but some<br />

slight differences may clarify<br />

their identity. Deep pressing<br />

troughs could be associated<br />

with wine production<br />

although they could<br />

also be used for olive pressing.<br />

Such is the spouted circular<br />

trough from the Late<br />

Bronze Age settlement near<br />

the Larnaka Salt Lake. Similar<br />

troughs are also known<br />

from Kommos in Crete.<br />

Horn-shaped vase<br />

used for drinking<br />

wine (Bellapais)<br />

There is little doubt that<br />

the level press was used for<br />

the production of wine as<br />

well as for the production<br />

of olive oil. For the<br />

latter this use was established<br />

on archaeological<br />

evidence at least from<br />

as early as the Late Bronze<br />

Age. Before the intro-<br />

duction of the lever press, which was in<br />

use in combination with a screw mechanism<br />

up to the middle of the present<br />

century, wine as well as olive oil were<br />

produced in simple rock-cut installations<br />

consisting of a sloping crushing or treading<br />

floor connected to a lower collecting<br />

vat. For the production of wine the<br />

treading floor was made deeper and usually<br />

larger in size. Such installations were<br />

recently discovered on a low rocky plateau<br />

in Geroskipou, overlooking the ancient<br />

city of Paphos, the capital of <strong>Cyprus</strong> during<br />

most of the Hellenistic and Roman<br />

periods.<br />

There is a variety of shapes and combinations<br />

of these installations which no<br />

doubt were used for the production of wine.<br />

The most common combination are two<br />

basins, at slightly different levels communicating<br />

through an open channel or<br />

through a hole between them. Treading<br />

took place in the first basin at a higher level<br />

and the juice was conveyed into the lower<br />

basin which is usually much bigger and<br />

deeper than upper one.<br />

In one case a canalis rotunda resembling<br />

a chariot wheel is also connected to a couple<br />

of basins. It is possible that this circular<br />

channel was used only when olives had<br />

to be crushed, but we cannot exclude the<br />

possibility of the use of a galeagra for the<br />

pressing of grapes.<br />

Small portable installations made from a<br />

monolithic stone are also known in some<br />

parts of the island. An example from Paphos<br />

represents a press bed rectangular in<br />

plan, connected with a rectangular receptacle.<br />

This monolithic installation works<br />

in combination with a wooden container

Detail from the Pyrgos jug. The human group represents a wine press scene. The first figure seems<br />

to be treading grapes in the trough and the must is collected in the circular basin<br />

(cofre) and most probably is the predecessor<br />

of the galeagra with screw.<br />

All types of presses known from classical<br />

literature appear in <strong>Cyprus</strong> throughout the<br />

Roman period, attesting to the close<br />

contacts between metropolitan centres and<br />

the provinces of the empire. The presence<br />

of stone stipites in at least five different sites<br />

provides direct evidence for the use of<br />

the lever and drum press as described in<br />

detail by Cato and demonstrated by the<br />

wine press in a Pompeiian house.<br />

The introduction of the screw in the pressing<br />

operation replaced all previous installations<br />

at least in large capacity wine<br />

producing units. Its application enabled<br />

19

20<br />

greater force to be brought in and, as a<br />

consequence, the press bed could be placed<br />

anywhere between the anchoring point<br />

and the screw. This type of press which<br />

was described in detail by Pliny was in use<br />

up to the middle of the 20th century at<br />

least in three different wineries on the<br />

island of <strong>Cyprus</strong>. During the Byzantine<br />

period it was the press par excellence in all<br />

church wineries used by the communities.<br />

Small mobile presses known as galeagra<br />

were introduced most probably during the<br />

later part of the Roman period as a result<br />

of the decentralisation of the economy.<br />

Their prototype is known in Pompeii in<br />

the form of a single screw direct press.<br />

Complete examples are still preserved in<br />

monasteries which continue old traditions.<br />

Kolossi Castle - where the Knights Templar produced their Commandaria wine<br />

The earliest preserved equipment is usually<br />

entirely constructed of wood.<br />

<strong>Cyprus</strong> wines were famous since the<br />

time of Strabo but this fact did not prevent<br />

the import of wines from world famous<br />

centres such as Rhodes, Thasos and Chios.<br />

Wine containers from these Aegean islands<br />

have been discovered in the Hellenistic<br />

cemetery of Paphos as well as in the Roman<br />

villas. The wine of <strong>Cyprus</strong> was also famous<br />

in the Middle Ages and King Francis I of<br />

France attempted to naturalize the <strong>Cyprus</strong><br />

grapevine at Fontainebleau, albeit without<br />

success. The Knights Templar who<br />

established their Grande Commanderie at<br />

Kolossi produced their own wine which<br />

became known as the vin de la Commanderie.<br />

This wine is still produced on the

Fikardou – pressing mechanism with wooden cast<br />

and screw<br />

island not by factories but traditionally by<br />

certain villages. The wine is known<br />

today as Commandaria and it is bottled at<br />

the Limassol factories under different commercial<br />

names.<br />

Etienne de Lusignan, writing in 1580,<br />

praises the wine of <strong>Cyprus</strong> as "the best in<br />

the world". This, he writes, is confirmed<br />

by Saint Bernard, Saint Thomas Aquinas,<br />

Saint Gregory and Saint Hilarion. Saint<br />

Gregory mentions that Solomon planted<br />

in his garden some vines which he had<br />

transported from <strong>Cyprus</strong>.<br />

Though there is no historical basis for<br />

the story that the sweet wine of <strong>Cyprus</strong><br />

was the main inducement of the Turkish<br />

Sultan Selim II for attacking and con-<br />

Large terracotta jar (pithari) used for storage<br />

quering <strong>Cyprus</strong> in 1571, the wine industry<br />

did not flourish during the period of<br />

Ottoman rule. The main obstacle was<br />

the triple taxation amounting to 28%, as<br />

well as some vine diseases.<br />

Commandaria wine, despite the oppression<br />

of both the Venetian and Turkish rulers,<br />

very strictly maintained its main traditional<br />

characteristics, the area where the vines<br />

were cultivated and the method of production.<br />

At present, the same method of<br />

making Commandaria continues to be<br />

as successful as during the period of the<br />

Crusades and it is probably the same method<br />

recorded by Hesiod 2000 years earlier.<br />

Commandaria is known since the Templars<br />

and Hospitallers, thus it is the wine<br />

with the oldest appellation of origin.<br />

21

22<br />

Karageorghis’ Memoirs<br />

The memoirs of the well-known Greek Cypriot archaeologist,<br />

professor and writer, Dr Vassos Karageorghis have recently been<br />

published in English by the Mediterranean Archaeological Museum<br />

of Stockholm under the title "A Lifetime in the Archaeology<br />

of <strong>Cyprus</strong>". The publication is a tribute paid by the Medelhavsmuseet<br />

to the man who ever since 1948, when, as a student<br />

he worked on an excavation conducted by the Swedish Professor<br />

Arne Furumark, developed warm ties with Swedish scholars<br />

and supported the study of Cypriote archaeology in Sweden.

In the foreword to the publication, the Director<br />

of the Medelhavsmuseet, Sanne Houby-<br />

Nielsen, appreciates that Dr Vassos Karageorghis<br />

"is the man whose enormous energy,<br />

whose never failing will to explore and<br />

understand ancient <strong>Cyprus</strong> no matter what<br />

political disasters, and whose boundless passion<br />

for the archaeology of <strong>Cyprus</strong> has highlighted<br />

<strong>Cyprus</strong> permanently on the scholarly<br />

map of the Mediterranean."<br />

The memoirs trace Vassos Karageorghis’<br />

personal and professional life from his childhood<br />

in the village of Trikomo, stricken<br />

with poverty during the years prior to the<br />

Second World War, through later years of academic<br />

and archaeological success, decorations<br />

and honorary doctorates. And throughout this<br />

extraordinary life, the driving force that propelled<br />

him to heights was his fierce will-power<br />

to succeed, his determination, his ambition<br />

"controlled to a degree which has beneficial<br />

effects" as he puts it.<br />

In the 226-page book, which took him<br />

three months to write, very little is left untouched<br />

and from the captivating narrative that<br />

keeps rolling, one can sense the satisfaction<br />

the writer relishes going through all those years.<br />

The memoirs start with the early years in<br />

the village of Trikomo where most families<br />

could hardly afford the bare necessities for<br />

their children. Primary school recollections<br />

are vivid; early rising and walking to school,<br />

a frugal breakfast of bread and olives, shoes<br />

worn only in winter, at church and during ceremonies<br />

at school, football played with a rag<br />

ball, the joy of learning and the instinctive<br />

will, that gradually became second nature,<br />

to be the best.<br />

As a pupil in the gymnasium in Nicosia, he<br />

worked hard to justify a scholarship and<br />

tasted the satisfaction of collecting all the<br />

prizes in the school throughout his secondary<br />

education.<br />

A pupil at the Pancyprian Gymnasium, in <strong>Jan</strong>uary<br />

1946<br />

With Jaqueline at Grenier, in 1950<br />

23

24<br />

After a short spell at the University of Athens,<br />

he was accepted to read Classics at University<br />

College, London; an experience he enjoyed<br />

enormously as he had the opportunity to<br />

listen to the fascinating lectures of Professor<br />

Martin Robertson, T.B.L. Webster, Gordon<br />

Childe, Mortimer Wheeler and other great<br />

names in archaeology.<br />

Back in <strong>Cyprus</strong> in 1952, he was appointed<br />

Assistant Curator at the <strong>Cyprus</strong> Museum,<br />

obtained his Ph.D. Doctorate from the University<br />

of London in 1957, was promoted to<br />

Curator in 1960 and in 1964 Director of<br />

the Department of Antiquities.<br />

His first task was to revive the publication of<br />

the Report of the Department of Antiquities<br />

of <strong>Cyprus</strong> and make it the annual scientific<br />

journal of the Department. His career as<br />

a civil servant was not easy but, as he remarks,<br />

Removing the soil from the bronze statuette decorating<br />

one of the chariots of tomb 79. Salamis, 1966<br />

"it was not time wasted as I tried to learn how<br />

to be efficient, how to take decisions and collaborate<br />

with other people."<br />

Meanwhile, in 1952, he started excavating<br />

at Salamis where he uncovered grandiose monuments:<br />

the Gymnasium, the Baths, the Theatre<br />

- inaugurated with Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex,<br />

performed by the pupils of the Famagusta<br />

Greek Gymnasium – and later, in 1963 the<br />

Royal Tombs with horses and chariots. The<br />

excavations at Salamis lasted twenty-two years<br />

(1952 - 1974), the most enjoyable period of<br />

his whole career abruptly interrupted by the<br />

Turkish invasion. "I saw my dreams crushed,<br />

and Salamis as well as my village disappeared<br />

all of a sudden from my life." There<br />

is ongoing grief for his "beloved site" and<br />

the 1974 occupation "a bleeding scar "on<br />

his soul and mind.<br />

After 1974, as a Director of the Department<br />

of Antiquities he managed to turn the limelight<br />

of research in the Mediterranean on<br />

Cypriote archaeology through a liberal policy<br />

which opened the island to international<br />

research. His archaeological reach has been<br />

wide and his friends have included eminent<br />

foreign professionals such as Einar Gjerstad,<br />

Mortimer Wheeler, Olivier Masson, Marguerite<br />

Yon, Jean Pouilloux, Claude Schaffer,<br />

Edgar Peltenburg, Franz-Georg Maier, Paul<br />

Åstrom and others.<br />

In 1989, having served in the Department of<br />

Antiquities for 37 years, and having seen his<br />

policy and vision being fulfilled, he retired.<br />

During his tenure at the Department of Antiquities<br />

he has lectured extensively as Visiting<br />

Professor at various universities such as the<br />

State University of New York, Université Laval,<br />

Quebec, the University of Aberdeen, Princeton<br />

N.J., U.S.A. or Visiting Fellow at Merton<br />

College, Oxford, All Souls College and<br />

Oxford etc.

Showing André Malraux, Minister of Culture, the exhibition ‘Treasures of <strong>Cyprus</strong>’ in Paris<br />

With Prof. F.G. Maier at Kouklia, in 1983<br />

With Marguerite Yon at Kition, in 1981<br />

In addition to his university appointments<br />

abroad, there are accounts of a series of international<br />

symposia following the success of the<br />

First Symposium on the "Myceneans in the<br />

Eastern Mediterranean" held in 1972. The<br />

proceedings of all the symposia were promptly<br />

published. In 1988, the Department of<br />

Greek and Roman antiquities of the British<br />

Museum organized an international archaeological<br />

symposium on "The First Millennium<br />

BC in <strong>Cyprus</strong>" in Dr Karageorghis’<br />

honour. It was one year after the opening of<br />

the A.G. Leventis Gallery of Cypriote Antiquities<br />

(on 9 December, 1987). The keeper<br />

of the Department, Dr B.F. Cook wrote in<br />

his preface:<br />

"……It was decided to devote the Greek and<br />

Roman Department’s annual colloquium to<br />

<strong>Cyprus</strong> and East Mediterranean in the Iron<br />

Age, and to dedicate the colloquium to Vassos<br />

Karageorghis, who has made such a distinguished<br />

contribution to the study of ancient<br />

<strong>Cyprus</strong>. He has done this in three ways: by<br />

his own scholarship, through administration<br />

and by what may be described as archaeological<br />

diplomacy. His scholarly achievement<br />

25

26<br />

After receiving the Onassis Prize ‘Olympia’ with<br />

Hans-Dietrich Genscher and Jimmy Carter, 1991<br />

resting on a host of excavations and publications<br />

is so well known and so highly admired<br />

as to need no further accolade here………"<br />

Honours were literally heaped upon him. He<br />

was conferred more than thirty distinctions,<br />

Honorary Doctor of more than ten universities,<br />

member of several academies, among<br />

them the Academy of Athens and the Royal<br />

Swedish Academy. He was awarded some prestigious<br />

prizes like the Onassis Prize ‘Olympia’<br />

in Athens, in 1991 for his efforts to trace<br />

and repatriate antiquities smuggled out of<br />

<strong>Cyprus</strong> after the 1974 war and the "Cavalli<br />

d’Oro di San Marco" in Venice, in 1996. One<br />

of the honours that seems to have touched<br />

him deeply was from his own village of Trikomo,<br />

a silver plaque with a representation of<br />

the old church of Ayios Iakovos.<br />

The memoirs also recall personal matters:<br />

meeting his French-born wife , Jaqueline, also<br />

an archaeologist, during his student years;<br />

their Bohemian "honeymoon" in the dig house<br />

built by the Swedish expedition at Vouni Palace<br />

where in spite of the primitive conditions they<br />

felt they were in a five-star hotel. He never<br />

fails to express his high regard for his discreet<br />

and understanding wife who "provided<br />

a serene family life, made my work easier<br />

and very often sacrificed much of her own<br />

time in helping me in my research", he admits.<br />

Instructing American and Canadian students.<br />

Summer school at Kition<br />

The couple have two children, a daughter,<br />

Clio who studied architecture and works at<br />

the Department of Museology at the Louvre<br />

Museum, a son, Andreas, Professor of<br />

Mathematics at the University of <strong>Cyprus</strong> and<br />

four grandchildren.<br />

In 1990, Vassos Karageorghis joined the Anastasios<br />

G. Leventis Foundation, and in 1992<br />

he accepted an appointment as the first Professor<br />

of Archaeology at the University of<br />

<strong>Cyprus</strong> and Director of the Archaeological<br />

Research Unit. He retired from the University<br />

of <strong>Cyprus</strong> in 1996 and since then he has<br />

been with the Leventis Foundation as Director<br />

of the <strong>Cyprus</strong> branch of the Foundation,<br />

member of the Board of Governors of the<br />

Foundation and a consultant for all archaeological<br />

projects of the Foundation in Greece<br />

and elsewhere.<br />

This has been a most rewarding period of<br />

his life. He considers that working with Constantinos<br />

Leventis, the fist Chairman of the<br />

Foundation, was an honour and a privilege,<br />

and there was absolute trust and consensus of<br />

opinions between them, sharing the vision for<br />

the conservation and promotion of the Greek<br />

cultural heritage wherever it manifests itself.<br />

Thus, he set about the task of resurrecting the<br />

Cypriote antiquities forgotten or hidden in<br />

the dark store-rooms of foreign museums. As

their return to the country of origin was not<br />

feasible, generous grants from the A.G. Leventis<br />

Foundation enabled a number of museums<br />

to create Cypriote Galleries: the Fitzwilliam<br />

Museum, Cambridge (1997), four galleries<br />

were assigned to the Cesnola Collection in the<br />

Metropolitan Museum, New York (2000), the<br />

National Museum of Denmark (2002), the<br />

British Museum, the Louvre, the Antikensammlung<br />

in Berlin, the Medelhavsmuseet in<br />

Stockholm, the Eretz Museum in Tel Aviv,<br />

the Royal Ontario Museum, the Kunsthistorisches<br />

Museum in Vienna, the Archaeological<br />

Museum of Odessa, the Pushkin Museum<br />

in Moscow, the Hermitage Museum in<br />

St. Petersburg…and the list is still growing.<br />

Illustrated catalogues were also published<br />

for all the collections.<br />

Apart from helping foreign museums to exhibit<br />

and publish their collections of Cypriote<br />

antiquities, Dr Karageorghis has derived particular<br />

pleasure from helping institutions in<br />

New member of the Academy of Athens, in 1992,<br />

with Professor Sakellariou<br />

foreign countries, especially those facing financial<br />

difficulties, to carry out cultural projects<br />

such as for example, the Archaeological Museum<br />

of Odessa, the libraries of the Universities<br />

of Mariupolis and Harkovo (Ukraine) and<br />

the ancient Odeon of the city of Plovdid (Philippoupolis)<br />

in Bulgaria.<br />

Dr Karageorghis continues to rise at dawn and<br />

do research work and writing in his office,<br />

in the sandstone neo-classical renovated building<br />

of the Leventis Foundation. With the beautiful<br />

garden surrounding it, the atmosphere<br />

is serene, an ideal place to work in.<br />

Writing his memoirs, he stresses, does not<br />

mean the end of active participation in archaeology<br />

and life in general. "There are still many<br />

moments to enjoy in life", he confesses,<br />

such as "the discovery of an interesting object<br />

in a museum store-room, the completion of<br />

a project like that of the archaeological Museum<br />

of Odessa, the satisfaction of seeing young<br />

and bright Cypriot men and women earning<br />

a Leventis scholarship to study for a<br />

doctorate in universities throughout the<br />

world…."<br />

Then, he adds, there is also "the smell of jasmine<br />

on a summer afternoon in the garden<br />

of my office and so much more".<br />

He insists that life is sweet as he launches new<br />

projects. "To be among the living is a blessing,<br />

and one should never be discouraged or<br />

unduly saddened by hardships and hurdles",<br />

he counsels.<br />

Closing the memoirs, he expresses his only<br />

wish, which is "to describe the day when I<br />

may visit my own native village again, and my<br />

beloved Salamis, and feel free to travel all over<br />

the small island which I tried to come to know<br />

in depth for so many years and to serve for<br />

more than half a century."<br />

<strong>27</strong>