70 Chaparral 2J - Motorsports Almanac

70 Chaparral 2J - Motorsports Almanac

70 Chaparral 2J - Motorsports Almanac

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

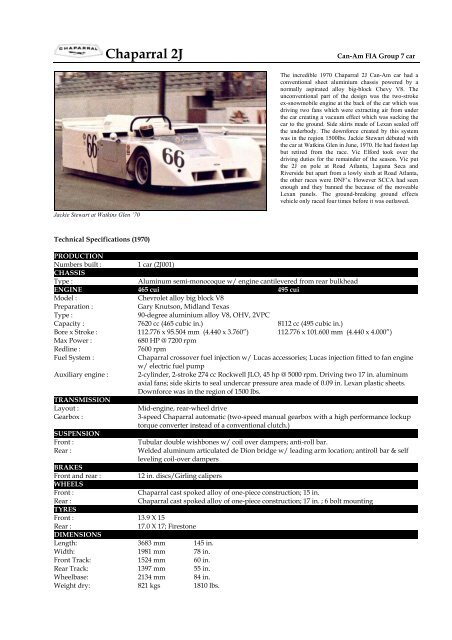

Jackie Stewart at Watkins Glen ’<strong>70</strong><br />

Technical Specifications (19<strong>70</strong>)<br />

<strong>Chaparral</strong> <strong>2J</strong> Can-Am FIA Group 7 car<br />

The incredible 19<strong>70</strong> <strong>Chaparral</strong> <strong>2J</strong> Can-Am car had a<br />

conventional sheet aluminium chassis powered by a<br />

normally aspirated alloy big-block Chevy V8. The<br />

unconventional part of the design was the two-stroke<br />

ex-snowmobile engine at the back of the car which was<br />

driving two fans which were extracting air from under<br />

the car creating a vacuum effect which was sucking the<br />

car to the ground. Side skirts made of Lexan sealed off<br />

the underbody. The downforce created by this system<br />

was in the region 1500lbs. Jackie Stewart débuted with<br />

the car at Watkins Glen in June, 19<strong>70</strong>. He had fastest lap<br />

but retired from the race. Vic Elford took over the<br />

driving duties for the remainder of the season. Vic put<br />

the <strong>2J</strong> on pole at Road Atlanta, Laguna Seca and<br />

Riverside but apart from a lowly sixth at Road Atlanta,<br />

the other races were DNF’s. However SCCA had seen<br />

enough and they banned the because of the moveable<br />

Lexan panels. The ground-breaking ground effects<br />

vehicle only raced four times before it was outlawed.<br />

PRODUCTION<br />

Numbers built : 1 car (<strong>2J</strong>001)<br />

CHASSIS<br />

Type : Aluminum semi-monocoque w/ engine cantilevered from rear bulkhead<br />

ENGINE 465 cui 495 cui<br />

Model : Chevrolet alloy big block V8<br />

Preparation : Gary Knutson, Midland Texas<br />

Type : 90-degree aluminium alloy V8, OHV, 2VPC<br />

Capacity : 7620 cc (465 cubic in.) 8112 cc (495 cubic in.)<br />

Bore x Stroke : 112.776 x 95.504 mm (4.440 x 3.760”) 112.776 x 101.600 mm (4.440 x 4.000”)<br />

Max Power : 680 HP @ 7200 rpm<br />

Redline : 7600 rpm<br />

Fuel System : <strong>Chaparral</strong> crossover fuel injection w/ Lucas accessories; Lucas injection fitted to fan engine<br />

w/ electric fuel pump<br />

Auxiliary engine : 2-cylinder, 2-stroke 274 cc Rockwell JLO, 45 hp @ 5000 rpm. Driving two 17 in. aluminum<br />

axial fans; side skirts to seal undercar pressure area made of 0.09 in. Lexan plastic sheets.<br />

Downforce was in the region of 1500 lbs.<br />

TRANSMISSION<br />

Layout : Mid-engine, rear-wheel drive<br />

Gearbox : 3-speed <strong>Chaparral</strong> automatic (two-speed manual gearbox with a high performance lockup<br />

torque converter instead of a conventional clutch.)<br />

SUSPENSION<br />

Front : Tubular double wishbones w/ coil over dampers; anti-roll bar.<br />

Rear : Welded aluminum articulated de Dion bridge w/ leading arm location; antiroll bar & self<br />

leveling coil-over dampers<br />

BRAKES<br />

Front and rear : 12 in. discs/Girling calipers<br />

WHEELS<br />

Front : <strong>Chaparral</strong> cast spoked alloy of one-piece construction; 15 in.<br />

Rear : <strong>Chaparral</strong> cast spoked alloy of one-piece construction; 17 in. ; 6 bolt mounting<br />

TYRES<br />

Front : 13.9 X 15<br />

Rear : 17.0 X 17; Firestone<br />

DIMENSIONS<br />

Length: 3683 mm 145 in.<br />

Width: 1981 mm 78 in.<br />

Front Track: 1524 mm 60 in.<br />

Rear Track: 1397 mm 55 in.<br />

Wheelbase: 2134 mm 84 in.<br />

Weight dry: 821 kgs 1810 lbs.

EOIN YOUNG TALKS TO VIC ELFORD ON DRIVING THE CHAPARRAL 19<strong>70</strong><br />

Currently the most controversial car on the CanAm sports car scene, the <strong>Chaparral</strong> <strong>2J</strong> ground effect car—or the " super<br />

sucker " or "vacuum cleaner" as it has been christened— has yet to finish a race. The controversy has been sparked off in<br />

CanAm by the alarming potential of the new car, which uses an auxiliary engine to drive suction fans which help to<br />

create a partial vacuum under the car, thereby "sucking" it down on to the road. The car first appeared at Watkins Glen<br />

in July with the then world champion, Jackie Stewart, at the wheel for his only appearance in the CanAm series. He set<br />

fastest lap in the race before the auxiliary 750 cc JLO two-stroke engine failed. With the exception of Laguna Seca, where<br />

the 8-litre Chevy engine blew up at the end of practice, the little JLO has always been the main problem with the<br />

complex new car. In the final race at Riverside, with the threat of protests and official SCCA banning hanging over the<br />

<strong>Chaparral</strong>, Elford qualified the car 2.2 secs faster than Denny Hulme's title-winning M8D McLaren. Through Riverside's<br />

Turn 9 loop at the end of the long straight the <strong>Chaparral</strong> was a clear half-second faster than the McLaren. "The big<br />

difference between the <strong>Chaparral</strong> and a conventional sports car like a 917 Porsche or anything else I've driven before, is<br />

this unreal sensation of being glued to the road," says Vic Elford. "Just to explain that a little, the partial vacuum that is<br />

created underneath allows the air pressure to work a little harder on the car, so that in effect the car has a down-force or<br />

loading on it of something like 1000 lbs over the weight of the car. Driving through a corner it has this much extra<br />

weight acting on the wheels. "As you start to approach the 'limit of adhesion on braking or cornering with a<br />

conventional racing car, whether it's a single-seater or a sports car, it starts to get a little bit out of shape. It will start to<br />

twitch a bit. The back starts to go from side to side, and the driver is kept busy at the wheel. With the <strong>Chaparral</strong>—at<br />

least at the stage I've reached with it—this just doesn't happen. When you want to go through a corner you simply turn<br />

the wheel and the car goes round as though it’s on rails. " I'm now beginning to get to the stage on some corners where I<br />

am reaching the limit, but even when this happens it's quite undramatic compared with a normal car. It just starts to<br />

slide out a little. In a faster corner the back starts to come out, but it really floats rather than slides, and I don't have to<br />

start twitching the wheel to hold it. I take off perhaps half an inch of lock, and the car remains in its smooth line through<br />

the corner. "The same thing is true under braking. I can brake considerably later than most cars on the way into corners<br />

because the car is so very firm and stable on the road. If I make a mistake, as I have done once or twice with the car on<br />

the approach to a corner and I enter it too fast, I can put the brakes on and start to slow it down when I'm on the way in<br />

or halfway through a corner. With a normal car if you started to do something like that, the chances are that you would<br />

lock a wheel instantly, if only for a fraction of a second, and slide off the road." This season CanAm fields have averaged<br />

27 cars, and with only perhaps half a dozen competitive machines there is a definite problem with slow traffic. Denny<br />

Hulme complained earlier in the season that the leaders were having to set their pace to that of the slowest car to avoid<br />

being run off the road while negotiating the tail-enders. In this respect, Elford was fortunate with the <strong>Chaparral</strong>. " The<br />

car is just so good in traffic. In any race you encounter slower cars as you get on through the event, and passing them<br />

with any normal car is often quite a problem because they tend to stick to the line and we have to go round the outside<br />

of them. This is where the <strong>2J</strong> shines, because it is so much better than conventional cars when you get it off the accepted<br />

line for a corner." Ask Vic about horsepower from the aluminium Chevy built down in the Midland, Texas, engine<br />

workshops by Gary Knutson, and Vic casts an anxious eye at <strong>Chaparral</strong> boss Jim Hall. Hall tells him to say the car has<br />

<strong>70</strong>0 horsepower and that it's on a par with the rest of the front runners. As with the McLaren team, there is always a<br />

doubt hanging over the CanAm races that perhaps the <strong>Chaparral</strong> team are running larger engines than they claim. This<br />

makes it easy for the slower drivers to excuse their lack of pace. Before Vic drove the car for the first time at Atlanta in<br />

mid-September, he went down to Midland to try the <strong>2J</strong> round Rattlesnake Raceway, Hall's private test track near his<br />

racing workshops. His main preoccupation then was learning to drive the automatic transmission car and braking with<br />

his left foot since there wasn't a clutch to worry about. Anticipating when he would race an automatic car, Elford had<br />

practised left foot braking from the day he took delivery of his automatic Ford Zodiac, but in moments of stress he<br />

tended to forget. "It was a bit dramatic occasionally because I would tramp on the wrong pedal coming up to traffic<br />

lights! When I drove the <strong>2J</strong> at Midland I did have a bit of a problem once or twice as I went to change gear with the<br />

selector lever, particularly changing up. I would tend to stamp on the brake pedal just as I flicked the lever through.<br />

This happened at Atlanta the first time I drove it in practice, but I soon got used to it." At Atlanta, Elford qualified on<br />

pole position, 1.26 secs faster than Hulme in the McLaren. Like the <strong>Chaparral</strong> he drives, "Quick Vic" tends to be a<br />

controversial personality, speaking the truth as he sees and understands it rather than playing the motor racing<br />

diplomat which seems to be vital these days. The facts are often not as important as how they are presented. Through<br />

personal determination and drive, Elford has graduated from a rally navigator to a Monte Carlo-winning rally driver<br />

with Porsche, and thence into top-line international motor racing. His appearances in Formula l to date have not been<br />

remarkable because the cars have tended to overshadow the driver's ability. Elford's plans for 1971 include the full<br />

CanAm Series, perhaps the three major speedway races at Indianapolis, Ontario and Pokeno, and the chance of a Grand<br />

Prix drive as well. He has been talking with Ron Tauranac about a Brabham ride. Elford is 35, wiry at 11 stone, and 'lives<br />

with his wife and family at Heston, only seven minutes from London Airport, which is an important consideration. His<br />

blonde wife Mary accompanies him to all his races. To gain a foothold in CanAm he drove less than competitive cars,<br />

flirted with the way-out knee-high AVS Shadow, and then suddenly appeared on top with the <strong>Chaparral</strong> at Atlanta. "I<br />

enjoy CanAm racing. These two-hour 200-mile sprint races are ideal for the driver, because you keep going pretty well<br />

flat out and you can have a good race for that time. The only criticism I've got about the CanAm Series is that there is so<br />

little competition. I don't mean for us, but with or without the <strong>Chaparral</strong> there are still only four or five cars that are<br />

really competitive. The two McLarens, the L&M Lola, the Autocoast, and that's about where it stops. After that it tends<br />

to become a bit of a procession and people trundle round knowing that they're going to finish somewhere in the money.<br />

In many cases when you get below the top six or seven they don’t race anyway—they're quite happy to drive around<br />

just to finish. The racing would certainly be a lot better if there were more factory entries either from America or from

Europe. From that point of view, ignoring the controversial side of it, the <strong>Chaparral</strong> must have increased the value of the<br />

CanAm Series as a public performance because it gives the public another competitive car." The <strong>Chaparral</strong> controversy<br />

is a dangerous one to get involved in without appearing to take sides. As Jim Hall says, if the issue was black or white<br />

there would be no problem. The <strong>Chaparral</strong> would be either legal or illegal, and he gives you to understand that he<br />

wouldn't have built the car if it was going to be illegal. The Sports Car Club of America regulations banned wings acting<br />

on the suspension at the end of last season, but their definitions in the specific area of aerodynamic aids were not as<br />

clear as they might have been and this is where the problem has arisen. The issue is grey round the borders, rather than<br />

a clear-cut black or white. Everyone wants the SCCA to clarify their regulations, and it appears that every team with the<br />

exception of <strong>Chaparral</strong> would like to see the <strong>2J</strong> banned. The McLaren team sees the sucker system increasing the cost of<br />

CanAm racing, which is already expensive when the same amount of extra pace could be obtained by allowing<br />

suspension-mounted wings back on CanAm cars. As Denny Hulme points out, wings were banned by the FIA because<br />

the wing structures were breaking only on some Grand Prix cars. There had been no breakages on CanAm wings. Peter<br />

Bryant, once a racing mechanic in Formula l with Reg Parnell, and designer and builder of the Autocoast Ti22 titanium<br />

car sponsored by Morris Industries until his recent controversial dismissal, points out that even though they have fitted<br />

a bigger 494 cu in engine, their times are slower than in 1969 when they ran with a wing. There would be astronomical<br />

development costs if others had to fit a sucker system of skirts and fans to their cars. "It took them two years to sort out<br />

the <strong>Chaparral</strong> and they have their own race track. It cost me $500 a day to hire Riverside. We could have built a car like<br />

the <strong>2J</strong>, but it would have meant asking more money from our sponsors, and good sponsors are hard to get." March<br />

designer Robin Herd estimates that the <strong>Chaparral</strong> is currently using only about 2 per cent of the suction that is<br />

theoretically available. "There are practical difficulties about getting more, but this figure can obviously be improved,"<br />

says Herd, who has been studying the system in America with a view to incorporating a similar arrangement on the<br />

Formula l March. "I personally don't think the car is illegal because I don't think it conflicts with the regulation about<br />

moving aerodynamic devices," says Elford. "However I prefer not to get too involved with the technical side of it—it's<br />

my job to drive it." Hall maintains that aerodynamics are concerned with air moving over a surface. The <strong>Chaparral</strong><br />

sucker system "does its thing" sitting still on the grid, so how does it get to be an "aerodynamic device" ? "If they ban the<br />

<strong>2J</strong> in CanAm racing I might as well go into Formula Vee or USAC or some sort of tight formula, which I didn't think<br />

CanAm was supposed to be," says Hall, having the last word.<br />

BIRTH OF CAN-AM RACING by Leon Mandel<br />

Car and Driver Editor Leon Mandel tells how Can-Am rules were set via 'after-hours' calls between Jim Hall and Tracy Bird. (This<br />

article appeared in the 1969 program guide for the Monterey Castrol GTX Grand Prix.)<br />

They take things very seriously at the International Sporting commission of the International Federation for<br />

Automobiles. They have to otherwise how could they have such long names? Still, it would come as something of a<br />

shock to them to know that the rules written for one of their premiere car categories was arrived at over the phone when<br />

the day got late enough so the telephone company charged a straight buck a minute to anywhere in the U.S. That's just<br />

about the way it happened with Group 7, or unlimited sports/racing cars and things have worked out very nicely since,<br />

thank-you. You can't have a race car unless you put it into a category - Parkinson must have a law about that<br />

somewhere - and all the categories are defined by the FIA which is the controlling body for auto sports and which lives<br />

its curious, bureaucratic life in Paris. Those countries which have active racing are FIA participants and it has happened,<br />

reasonably enough, that each promotes particular kinds of cars - perhaps according to terrain, perhaps according to<br />

national character. The result is that Formula 1, the panatela-like single seaters which vie for world championship, are<br />

the vital concern of France and Italy and England while sedans, which race in more countries, have broaded based rule<br />

makers. The big unlimited sports / racing cars, known to the FIA as Appendix J, Group 7 cars, are almost exclusively<br />

North American and it was in North America that their genesis came. Well, almost. It was certainly in North America<br />

where the rules defining them were written. It may have been that the very first G/7 cars as we know them today were<br />

the Poopers built by Pete Lovely in the Pacific Northwest and Tippy Lipe in upstate New York in 1951. There were<br />

Cooper record cars, streamliners, with Prosche engines and they went so fast no one could believe it. It was a kind of<br />

notional expression of irreverence toward the already-created car which gave them birth. Of course you could get a<br />

Cooper, and certainly you could get a Prosche, but a Pooper? The whole idea was to capitalize on ingenuity and build a<br />

car for local competition and to hell with the world over there. The flower really bloomed in southern California and to<br />

some extent in eastern Canada where clean, effective spedials were being built with some regularity. But they, unlike<br />

the Pooper, were front engined cars and their areas of competition were limited. It was only after local constructors saw<br />

themselves being beaten by the factory Porsches that the modern-day G/7 car was born. It was born in rear engine form<br />

and true to its orgins, it was a hybrid. The impetus came from a very European source, the appearance money syndrome.<br />

<strong>Chaparral</strong>-builder Jim Hall was not in the least pleased that appearance money, or starting money, was being paid in<br />

Europe and not in the U.S. and his complaints were becoming more and more vocal. To quiet him, the racing<br />

establishment did what establishments are forever doing - it invited him to become a part of the administration and he<br />

accepted. From then on he worked untiringly for U.S.-Canadian series of races with points fund money to replace<br />

appearance money and when it became known to Sports Car Club of America Competitions Board Chairman (now<br />

SCCA Executive Director) A. Tracy Bird and Hall that the international ruling body was willing to accept a formula for<br />

such racing, the two worked out rules for what was to be G/7 - on the telephone. It was not a formal proceeding. Each<br />

had a car of his own, Hall a <strong>Chaparral</strong> and Bird a Cooper, and they would call each other after 8 p.m. when rates were<br />

cheap and propose wording for the new rules. One would mention scoops and the other would tell him to hang on and<br />

rush out to measure scoop size on the car sitting in his garage, rush back in and either agree or propose a modification.<br />

The resulting rules were submitted to the SCCA's Competitions Director (now Director of Professional Racing) Jim

Kaser and from there, via the Canadians to the international group in Paris where they were accepted. Thus the<br />

American formula was made legitmate and the way was paved for the Canadian-American Challenge Cup series. While<br />

that fateful meeting of the CSI (Commission Sportif of the FIA) nailed it down, the rear engined G/7 cars were already<br />

beginning to thrive on North American race circuits. And the turing point had probably been the summer of 1963 at<br />

Continental Divide Raceways. With a United States Road Racing series already established, North American<br />

constructors were working hard at beating the Porsches with a combination British chassis and American stock block<br />

engine. Indianapolis great Roger Ward had appeared in a Cooper with a Buick engine in it as long ago as 1957, and<br />

Stirling Moss was the principal stockholder in California's Laguna Seca track with two wins in his Lotus 19-2.7 but his<br />

had a Coventry Climax engine. The real big bore engines, the everyday engines (much modified), had yet to make any<br />

impact. The chassis builders, including Roger Penske and the famous Zerex Special, were way ahead of the engine men.<br />

Then in August of '63 the USRRC at CDR turned the tide. Bob Holbert won it in a King Cobra, a Cooper-Ford with Bob<br />

Bondurant right behind in a similar car. Dave McDonald in a front-engine car was third. Chuck Daigh in a Cooper-<br />

Chevrolet was forth and the Porsches, driven by such accomplished drivers as Don Wester, were nowhere to be seen.<br />

That put the American Engine Solution in the limelight, and such things have been going in that direction ever since.<br />

The British, who were faced with a choice between Formula 2, a lesser version of F/1 and Group 7, decided to go with<br />

the open wheel cars - their pool of sponsors couldn't support both; and now they regret it. The Europeans who couldn't<br />

have been bothered have begun to take notice and for two years Ferrari has had a token respresentation in the Can-Am.<br />

This year he's serious. And no one would be particularly surprised if a Prosche showed - built to American Formula. It<br />

was a long struggle, but these days, Can-Am makes the going great.<br />

VIC ELFORD AND THE VACUUM CLEANER By Andrew S. Hartwell<br />

This article appeared in the "Through The Esses" column in All Race Magazine Issue 29.<br />

Among the many legends of motor racing there stands two men, working on opposite sides of the Atlantic ocean, who<br />

brought innovation to the race track time and again. In Europe, that man was Colin Chapman. His work with the Lotus<br />

Grand Prix cars saw radical changes with each new season and his cars were successfully campaigned by such<br />

legendary drivers as Jimmy Clark and Graham Hill. On the American side of the ocean, a tall Texas oilman and student<br />

of engineering by the name of Jim Hall was also bringing some innovative and radical thinking to the sportscar scene.<br />

His <strong>Chaparral</strong> creations were the first to introduce effectively designed air dams and spoilers ranging from the tabs<br />

attached to the earliest 2C model to the driver-controlled high wing 'flipper' on the astoundingly different looking 2E, all<br />

the way through to his most idealistically inspired creation, the <strong>2J</strong>. This is the car that would forever be known as the<br />

'vacuum cleaner'. Introduced in 19<strong>70</strong>, making its race debut at the Watkins Glen Can-Am race at the hands of world<br />

champion Jackie Stewart, the <strong>2J</strong> had no precedent to compare it to. It was an angular car at the front and just a big box<br />

at the back. And the back was a place that housed two large 17-inch fans driven by a JLO - Rockwell 45 hp snowmobile<br />

engine. The fans purpose was to literally 'suck' the air from under the car and shoot it out the back. They acted like<br />

reverse fans pulling air through and then out, thus giving the car amazing grip. The entire car was fitted with a 'skirt'<br />

made of a then-new material called Lexan. Plastic-like in construction, the skirt acted as a windbreak allowing the fans<br />

to pull out the air thus sucking the car onto the pavement. The amount of grip delivered by the twin fan units was so<br />

incredibly high that cornering speeds could be reached that no one else could ever hope to match in a more<br />

conventionally designed car. The <strong>2J</strong> represented both the latest in aerodynamic subterfuge and a threat to the sanctity of<br />

the motor racing establishment that existed at the time. It could really 'go' on the track, but there were those who just<br />

wanted it to 'go away'. The car only ran for one glorious season (19<strong>70</strong>) and like all new cars it had it's share of teething<br />

pains. Unfortunately it never had a chance to grow up as the sanctioning body, with more than a bit of prodding from<br />

the <strong>Chaparral</strong>'s competitors, decided to outlaw the technology after the season had ended. While the car had just one<br />

incomplete season of racing, it was fortunate to have had two outstanding drivers to race it. After Stewarts initial run,<br />

Englishman Vic Elford was hired to bring the car home with a win. Hall had said he needed to find someone who could<br />

handle the cornering power of his creation, as he didn't think he could do it himself. To best address his need for a<br />

qualified pilot he sought out Elford, who had established himself as one of the best in endurance racing with drives for<br />

Porsche at Le Mans and other venues. Elford was not able to bring the car a win in its maiden and final season but the<br />

road that leads to the podium was one 'Quick Vic' really enjoyed traveling on. I had a wonderful conversation with Vic<br />

Elford at the Porsche Rennsport Reunion at Lime Rock Park recently. I asked him to tell me of the '<strong>70</strong> season and his<br />

turn at the controls of the vacuum cleaner car. It is an interesting tale of speed, downforce, resentment and control.<br />

Eavesdrop for a minute. Vic Elford: "I was just trying to remember the first time I drove the <strong>Chaparral</strong> <strong>2J</strong> and I recall it<br />

was at Rattlesnake Raceway, Jim Hall's private track. He got me down there for a couple of days to get the feel for it<br />

because it was 'different' to drive. The first time I raced it was at Road Atlanta (in the Can-Am Championship) when I<br />

was about 2.5 seconds quicker than Denny (Hulme) for pole position. Then I drove it at Laguna Seca and again at<br />

Riverside. "Do you remember the old Riverside turn 9? It was a long, long, long fast 180-degree right-hander just before<br />

the pits. During practice I came up behind Denny (in the McLaren M8D-Chevrolet) on the way into that corner and it<br />

was a very fast corner. Not quite flat but for me very close to it, and I remember driving around the outside of Denny<br />

(laughing) and he just pulled off into the pit lane absolutely pissed off! He took his helmet off and sat on the pit wall<br />

and sulked for the rest of the practice session. I had beaten his time by about 2.5 seconds. It was a wonderful car to<br />

drive! Tell me about the cars automatic transmission: "It was a semi-automatic transmission, it wasn't fully automatic.<br />

It had a three-speed transmission with a torque converter and a lock-up at 5,000 rpm. It was quite complicated to get it<br />

running. The steering column went down between your two feet so the left foot could only work the brake and the right<br />

foot could only work the gas pedal. Was driving a car set up that way something of a shock to you? "By sheer luck,<br />

really, a year earlier I had a bad accident at the Nurburgring in the Grand Prix, which destroyed my shoulder. I was in

physical therapy for weeks, suffering day after day. At that time, Grand Prix drivers all used to have a complimentary<br />

car from the FORD motor company in Great Britain. We could have what we liked and, as I had a wife and a couple of<br />

kids then, I had a big Zodiac, which was the top of the line sedan in England. The car was an automatic and I had never<br />

had an automatic car before so while I had it I thought I'll learn to brake with my left foot. "I had never done it before so<br />

it took me about three months to really learn to do it efficiently. Now I do it automatically every time I get in a car with<br />

an automatic transmission. I always break with my left foot now. I wasn't doing it in anticipation of the ride in the<br />

<strong>Chaparral</strong>; I just decided I was going to learn how to do it. When it came time to drive the <strong>2J</strong> of course, I was ready for<br />

it, as I had no trouble with it. Did the cars transmission put you at a disadvantage at the start? "At Road Atlanta, Denny<br />

Hulme was in the first McLaren and Peter Gethin was in the second one and they all blew me away at the start. I<br />

remember that, at 5,000 rpm's the transmission dogs would just lock up. From there on it was solid drive and that went<br />

all the way up to 7,600 rpm, which was about maximum in those days. One of the problems was we only had three<br />

speeds while the McLaren's and the Lola's all had four speeds. So it didn't matter where I was on the pole because two<br />

or three cars would just blow me away at the start. "We went around to turns 6 to 7, not really an overtaking place, and I<br />

followed Peter through turn 6 and as we were sort of half way to turn 7 he was braking. I thought now that's a shame,<br />

he must have some sort of problem. And I went past him on braking and then I did the same to the other cars in front<br />

on the subsequent laps and it dawned on me that they didn't have a problem; they just couldn't brake where I could! It<br />

was a great feeling (laughing). "The amazing thing about it was that it didn't rely on aerodynamics so it worked as well<br />

on slow corners as it did on fast corners. Where as with the McLaren, of course, the faster you go the more downforce<br />

you have so they were great in fast corners but just normal in slow corners. Were the fans on all during the race? "The<br />

fans were on all the time. The start up procedure was I had to sit with my foot on the brake because once they started<br />

up the two-stroke fans they could actually move the car forward. Not quickly, but it would start creeping forward. I<br />

had to put the transmission in first gear then start the main engine and it would just sit there on the torque converter.<br />

As soon as I took my foot off I could accelerate away. "I once did the Acropolis rally with a FORD Lotus Cortina that<br />

had no clutch for two thirds of the race. I was pretty good at changing gears without using a clutch and you had to do<br />

that in the <strong>Chaparral</strong> as well. It meant I had to synchronize the revs from first to second and second to third and then<br />

back down through the box too. And you have to do this corner after corner. "The moment the little snowmobile engine<br />

started it ran at a pretty constant 5,000 rpm, I think- the car then sucked itself down about two inches with the Lexan<br />

skirt scrapping the ground. I didn't finish at Riverside because the little engine broke going through turn 9 - the long fast<br />

corner - and the car was perfect until it suddenly came up two inches! That moved the tires up to where you no longer<br />

had 18 inches of rubber on the road you had about three inches! Very exciting! What put an end to the <strong>2J</strong>? "The one<br />

single guy who really killed the technology of the <strong>2J</strong> was Teddy Mayer, the team boss at McLaren - and a lawyer in the<br />

bargain. The Can-Am had been exclusively the property of the McLaren for what, three years or so, and so he could see<br />

all the money going away and so basically he killed it. And I think the SCCA was weak in not standing up to him<br />

really." If it hadn't been banned? "Everybody would have followed suit, at least in Can-Am. And I think it would have<br />

probably lasted several years and then there would have been a reevaluation of the rules to level the playing field and<br />

trying to cut the speeds down, because the <strong>2J</strong> was the start of really high cornering speeds." Before Hall built the <strong>2J</strong>,<br />

another white but supposed-to-be-wingless <strong>Chaparral</strong> had come off the drawing board. It was the ill-fated 2H. Dubbed<br />

the 'white whale' for it's unusually narrow and long shape - a shape made all the more ugly when a huge wing was<br />

mounted in the middle of the car in an attempt to counteract undesirable aerodynamic effects - the car never got sorted<br />

out and soon made way for the <strong>2J</strong>. But the 2H was one more historic marker placed on the trail of sportscar racing.<br />

While Jim Hall and Vic Elford were partners in bringing a radical idea to fruition with the <strong>2J</strong>, it seems not everyone<br />

loves a winner. But there were a few wonderful days in the sun for Elford and Hall, and the <strong>Chaparral</strong> cars did run like<br />

the desert birds for which they are named. Too bad there had to be a Coyote waiting in the tumbleweeds. Texan Jim<br />

Hall began racing sportscars in SCCA events in the early '50s. He became pretty good at it. In 1957 he moved from<br />

Dallas to Midland to be closer to his family's oil business. There he joined a syndicate that built and ran a sportscar track<br />

called Rattlesmake Raceway. It was never very good as a racing facility, so when Hall formed <strong>Chaparral</strong> in the early '60s,<br />

he acquired the track as a private test facility and built his factory there. Early <strong>Chaparral</strong>s competed in various sportscar<br />

races across the country including the 24 Hours of Daytona and the 12 Hours of Sebring. From 1963-1965, <strong>Chaparral</strong>s<br />

driven by Hall and Hap Sharp, dominated SCCA racing. <strong>Chaparral</strong> was well known for aerodynamic innovations. Hall<br />

was one of the first to put "air-dams" under a car's chin to keep the front of the car on the ground. He was also one of the<br />

first to put a "spoiler" on the rear deck edge to keep the back end on the ground. When the Can-Am was formed in 1966,<br />

<strong>Chaparral</strong> joined in. In 1966, Hall shocked the racing community by mounting a wing, upside down, on two vertical<br />

struts on the back of his <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2E cars. Working like an airplane wing, only upside down, it generated downforce<br />

(instead of lift) to keep the rear of the car stuck to the ground. The radiators were relocated from the front of the car to<br />

the sides so that a wing could be mounted inside the front bodywork to keep the front down. The wings were also<br />

movable. The <strong>Chaparral</strong>s used an automatic transmission, so there was no clutch pedal, which allowed Hall to add a<br />

third pedal. While accelerating, the driver would hold the pedal down with his left foot. This kept the wings horizontal<br />

for less drag. Releasing the pedal put the wings in an angled position, for greater downforce in the corners (the<br />

increased drag also helping slow the car). Jim Hall teamed with Phil Hill, who had become the first American to win the<br />

Formula One World Driving Championship in 1961, to drive <strong>Chaparral</strong>s in 1966. <strong>Chaparral</strong>s set fastest qualifying time<br />

twice that season (Hall once and Hill once) and Hill gained the team's first Can-Am win on October 16, 1966, at Laguna<br />

Seca, California. For 1967, <strong>Chaparral</strong> entered a revised version of the 2E called the 2G. The 2G was wider and<br />

aerodynamically cleaner than the 2E, but the aluminum chassis wasn't built for the amount of torque being put out by<br />

the team's 427 cubic inch Chevrolet motors. (It was better suited to the 327 cubic inch engine used in their endurance<br />

racing coupes, but they were committed to the big block.) The team only entered one car for '67, with Hall at the wheel.

They managed neither a pole position (fastest qualifier) nor any wins. Their best finishes were a pair of seconds. Hall<br />

had planned on running his new, 2H in 1968, but development bugs kept it from debuting until 1969. He would be<br />

forced to race the 2G in 1968. The result was one pole but no wins. Las Vegas, the sixth and final race of the season, was<br />

also the last race as a driver for Jim Hall. Late in the race, his <strong>Chaparral</strong> collided with a backmarker, was launched into<br />

the air, and landed upside down. Hall was rescued from the ensuing fire, but his severely broken legs lead to his<br />

retirement from driving. Although introduced by Jim Hall in 1966, not many cars besides the <strong>Chaparral</strong>s used high<br />

wings for extra downforce. Several cars carried them in 1969, but Hall himself introduced another radical car, the<br />

previously mentioned <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2H. Dubbed "The Great White Whale", because it looked like one, it would not be one<br />

of Hall's better efforts. It was originally designed as a narrow coupe with windows in the doors because the driver sat so<br />

low in the body. Driver John Surtees felt that visibility was poor and had Hall take the car's canopy off and raise the<br />

driver's seat. The vestigial passenger seat remained under the bodywork. There was a low wing at the back of the body.<br />

This <strong>Chaparral</strong> didn't cut it. The team bought a McLaren M12 to use while they continued to sort the 2H out. At one<br />

point in the season, the 2H wore a huge wing in the center of the car with the struts mounted to the sides of the car.<br />

Quite possibly, the most bizarre looking racer ever built. Although Hall and Surtees never got along well, Hall took full<br />

responsibility for the failure. He felt that had he not broken his legs, which kept him from test driving, he could have<br />

sorted the car out. At any rate, the team's direction changed for 19<strong>70</strong>. The FIA, auto racing's world ruling body,<br />

outlawed tall wings (from now on they would have to be near the bodywork) after 1969 because of some spectacular<br />

accidents that had occurred to F1 racers. Also, "movable" aerodynamic devices such as <strong>Chaparral</strong>'s flipper wings were<br />

outlawed. Jim Hall's answer to this, the <strong>Chaparral</strong> <strong>2J</strong>, did not debut until the third race of the 19<strong>70</strong> Can-Am season in<br />

July at Watkins Glen, New York. The <strong>2J</strong> was as radical as the 2E and 2H had been. Maybe more so. The car looked like a<br />

white brick. A very fast white brick. The car carried two motors. A 465 cubic inch Chevy V8 powered the rear wheels<br />

and a 274 cc Rockwell snowmobile engine powered a pair of "sucker" fans in the rear bodywork. The fans sucked air out<br />

from under the car, creating a vacuum that held the <strong>2J</strong> on the track. Sliding Lexan skirts were placed around the bottom<br />

edge of the body to seal the "plenum" area under the car. Enough suction could be generated to hold the car upside<br />

down on the ceiling of a room! Where a wing generates downforce (good) it also generates drag (bad). The suction<br />

device generated downforce with no drag loss. Reigning F1 World Driving Champion Jackie Stewart qualified the <strong>2J</strong><br />

third at Watkins Glen and drove the race's fastest lap, but his race was cut short by brake problems. The <strong>Chaparral</strong> team<br />

missed the next three races but returned to competition in September at Road Atlanta. They also brought a new driver<br />

with them, Vic Elford. Elford drove the <strong>2J</strong> in three of the remaining four races. (The team would miss one more race.)<br />

Elford was fastest qualifier in all three of those races but he only finished one (sixth at Road Atlanta). Something always<br />

broke. But the competition felt that, with a year of experience under their belt, the <strong>Chaparral</strong> team would bury them in<br />

1971. Competitors were always lobbying the SCCA to ban the <strong>2J</strong>. At the end of the season it was. The sliding Lexan<br />

skirts were said to have violated the "moveable aerodynamic device" ban. With that, Jim Hall closed up shop. An era in<br />

international autoracing had come to a close. Hall did return to autoracing in 1980 with the <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2K Indycar.<br />

Johnny Rutherford won the Indy 500 that year in the car. Hall owned a CART Indycar team into the 1990s, but bought<br />

his team's chassis from other companies.<br />

HALL’S CHAPARRALS<br />

In 1961, race car builders Tom Barnes and Dick Troutman approached Texas-born race driver Jim Hall about a sports<br />

racer they had designed. Although initially called the "Riverside," that was the beginning of the <strong>Chaparral</strong> legacy. The<br />

<strong>Chaparral</strong> 1 was a Chevy-powered, front-engined car that had a common heritage with the Scarab rear-engined racer<br />

that was previously designed by Barnes and Troutman. Its first race was at a Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) race at<br />

Laguna Seca, California in June 1961. Jim Hall brought his new <strong>Chaparral</strong> 1 to a 2nd place finish. Hall raced the<br />

<strong>Chaparral</strong> three more times in 1961, with a 3rd place at the October Riverside L.A. Time Grand Prix and DNFs at<br />

another Laguna Seca race and at the Nassau Speed Week main event. Jim Hall drove the <strong>Chaparral</strong> 1 to victories at the<br />

Road America Sprints in June 1962 and the Road America 500 in September 1962. The next incarnation of the <strong>Chaparral</strong><br />

was originally intended to be a coupe-bodied sports racer patterned after Chevrolet's Corvair Monza GT concept car of<br />

1962. The eventual open cockpit <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2A, however, maintained the pointed nose and other design elements of the<br />

Monza GT. The <strong>Chaparral</strong>'s first race, at the 1963 Riverside L.A. Times Grand Prix, ended in a DNF for Jim Hall. but this<br />

was to be the beginning of one of the most successful, if short-lived, runs in American unlimited sports car history.<br />

Running in the U.S. Road Racing Championship and a series of Pacific fall races (which included races at Riverside and<br />

Laguna Seca), Jim Hall and Hap Sharp took their <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2s to an incredible 7 1sts and 7 2nds in 16 races in 1964, and<br />

16 1sts and 9 2nds in 21 races in 1965! Among the 1965 victories was the 12 Hours of Sebring, a race that saw Jim Hall's<br />

open cockpit racer beat Carroll Shelby's coupe-bodied Cobras and GT-40s, although the skies open to flood the race<br />

track during the early evening hours. Jim Hall was known for innovation, and that innovation started to show itself in<br />

the <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2C, an upgraded version of the <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2A that included a hydraulic rear spoiler that the driver could<br />

raise in the turns and lower for less drag in the straightaways. The next evolution of Hall's racer, the <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2E made<br />

it's debut at the Can-Am race at Bridgehampton, New York in September 1966. This unique racer had a huge, highmounted<br />

wing that, like the 2C's spoiler, was hydraulically operated to shift its angle depending on the track conditions.<br />

The <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2E and a later development versionn called the 2G had short racing careers, competing in 17 Can-Am<br />

races during 1966 through 1969. Although the car was unbeatable, it had reliability problems that resulted in many<br />

DNFs. The <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2Es and 2Gs actually only scored 2 Can-Am victories and 6 2nd place finishes. Jim Hall's driving<br />

career came to an unfortunate and almost fatal end in November 1967, when his <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2G struck the back of Lothar<br />

Motschenbacher's McLaren and was catapulted into the air. The car landed on its tail and flipped over on its back,<br />

resulting in Hall suffering two badly broken legs and a dislocated jaw. Despite the end of his driving career, Jim Hall

continued to create innovative open-cockpit sports cars. The 1969 <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2H was originally designed to be a<br />

streamlined coupe, with the driver in a prone position looking through a plexiglass nose. However, John Surtees, the<br />

driver hired by Jim Hall to drive the car, convinced the team to open the cockpit for a more conventional appearance<br />

and driver position. Although the innovative design may have eventually proved successful, differences of opinion<br />

between Surtees and Hall resulted in the <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2H never living up to the team's expectations. The car's best finish<br />

was a 4th at a race in Edmonton, Canada. To appease his driver, Hall even purchased a McLaren M12 for use in the 1969<br />

Can-Am series, but that car's best finish was a 3rd place finish at the Mosport Can-Am race. The last U.S. road racing<br />

<strong>Chaparral</strong> was the <strong>2J</strong>, a boxy design that hid an innovation so potentially successful that it resulted in the car being<br />

banned. The <strong>Chaparral</strong> <strong>2J</strong>, affectionately known as the "Sucker Car," sported a snowmobile engine attached to two fans<br />

that sucked air from the bottom of the car and pushed it out the back. This created a vacuum that held the <strong>Chaparral</strong> <strong>2J</strong><br />

to the track like it was on rails. Although it raced only four times, not long enough to work out some of its "bugs," the <strong>2J</strong><br />

gave warning to competitors that it would be unbeatable when its reliability problems were solved. Unfortunately for<br />

Jim Hall, however, the FIA, the international race sanctioning body, banned the <strong>2J</strong> because it used "illegal moving<br />

aerodynamic devices." In 1966 and 1967, Jim Hall decided to take his successful <strong>Chaparral</strong>s to Europe to compete in the<br />

FIA World Sports Prototype Championship, going up against the world's best, including Shelby's GT-40s, Ferrari, and<br />

Porsche. The car used for the 1966 FIA season was the <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2D, a coupe version of the 2A that was very similar to<br />

Hall's original design for the <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2A. The resemblence to the Chevrolet Monza GT concept car is unmistakable.<br />

With drivers Phil Hill and Jo Bonnier, the <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2D managed a victory in the 1000 Km race at the demanding<br />

Nurburgring in Germany. The car DNF'd in three other FIA races that year. Although the 2D also competed in the first<br />

two races of the 1967 FIA season (Daytona and Sebring), the main entrant was the new <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2F, a coupe version of<br />

the high-winged 2E. Although the car was competitive, Phil Hill and Mike Spence only finished one of the eight FIA<br />

races in which it was entered. At least the last race (also the car's last race) resulted in a victory in the 500 Km. race at<br />

Brands Hatch. Jim Hall's <strong>Chaparral</strong>s didn't win any international championships, as Carroll Shelby's Cobras and GT-<br />

40s did. But Jim Hall and his <strong>Chaparral</strong>s dominated unlimited class sports car racing in the United States during the<br />

mid-1960s. To this day, very few race cars, of any type, have included and successfully demonstrated the aerodynamic<br />

innovations that Jim Hall built into succeeding versions of his <strong>Chaparral</strong>. The "Texas Road Runners" are truly a part of<br />

American racing history!<br />

JIM HALL AND HIS FABLED CHAPARRALS by Pete Lyons<br />

Troy Rogers stands ready beside the louver-bedecked <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2, just as he used to. Jim Hall settles once more into the<br />

composite cockpit that he molded around himself back in 1963. It fits his still-lean, lanky frame perfectly—as does his<br />

old driver’s suit. The ingrained starting drill comes back as readily: First plant your left foot on the brake and shove the<br />

shifter into low, and only then fire the Chevy. The aluminum small-block lights instantly, its eight stub stacks emitting a<br />

vigorous, eager crackle. At least old race cars can hold onto their youth. This one is already straining to go, churning the<br />

oil in the torque converter, held back only by the brakes. Hall simply releases them, and this ivory apparition from a<br />

distant time is free to run again. As the historic machine accelerates onto the Road America track, scene of two of its<br />

great victories in 1965, the converter keeps the engine at a constant growl while velocity builds. It’s like the steady roar<br />

of a Reno air racer on takeoff... except that here a resonance comes back from deep in the Wisconsin woods. Is it merely<br />

sonic reflection from thousands of trees? Or is it an echo from the glory years? That exciting era when the Road Runners<br />

from Texas were not only the dominant force in American sports car racing, but an astounding, fabulous, phenomenal<br />

leap forward in the world’s very conception of a racing car. If today, looking back, the whole <strong>Chaparral</strong> story sounds<br />

like a myth... well, that’s pretty much how it seemed then, too. See if you can sell this one to the movies. There’s a little<br />

bunch of amateur sports car racers, see, who hail from the scrub-brush obscurity of West Texas. Just the place to<br />

manufacture state-of-the-art road race cars, right? Anyway, every so often these guys pop up at the continent’s top<br />

tracks, where they unload home-built specials so novel they drop jaws, and so fast they threaten to win every time out.<br />

Plastic chassis... aluminum replicas of iron production engines... “automatic” transmissions... driver-operable “flipper”<br />

wings mounted upside-down... one car that is half roadster, half coupe... another with a second engine and extractor<br />

fans to clamp the car to the road like a giant suction cup... all produced in a secret lab, complete with a private test track.<br />

Hey, let’s call it “Rattlesnake Raceway.” Our hero is a wealthy young oilman who’s tall and slim and looks good in a<br />

cowboy hat. Plus, he’s an excellent race driver—a former F1 driver, no less—as well as a brilliant, imaginative race car<br />

designer. And, and, how about we give him a clandestine engineering liaison with the world’s largest automaker.<br />

Preposterous! But true. All that happened. And here to prove it is tall Jim Hall with four of his <strong>Chaparral</strong>s. His long<br />

racing career finally, firmly behind him, Hall is living a quiet, reclusive life. He and wife Sandy have become very<br />

serious about golf. But only days shy of his 66th birthday, he has come to RA to be grand marshal at the BRIC—the<br />

Brian Redman International Challenge, a vintage event named for the driver who won three champion-ships in Hallmanaged<br />

F5000 cars, 1974-76. Grand marshal: It’s a cloak of honor that must drape awkwardly over the shoulders of a<br />

hard-core, no-nonsense racer. And as the weekend develops, this very private man must be surprised by the endless<br />

throngs of people who want to see him, speak with him, ask him to sign something. The surprise is evident in the<br />

gracious “Thank you,” he returns along with the autograph. Other things feel unfamiliar today, too. <strong>Chaparral</strong> Cars<br />

used to tow its fantastic machines on open trailers; to the team they were just disposable raceware. This time they’ve<br />

been transported in 18-wheel splendor; rumor says they’ve been specially insured for $2 million—each. Back home in<br />

Midland, plans are afoot to build a museum around them. Opening is scheduled for 2003. It won’t have to be a very big<br />

building. People who remember all those Road Runners in all those races are always amazed to learn the actual total<br />

number of <strong>Chaparral</strong>-built sports car chassis: just seven. Six still exist, now lovingly restored by Rogers, one of the<br />

craftsmen who built them originally in Texas. (A series of five front-engined predecessors named <strong>Chaparral</strong> 1s came

from Troutman and Barnes in California. One of those was at the BRIC, too.) So few, really? Well, <strong>Chaparral</strong> Cars was<br />

small, efficient and unromantic, and kept turning one car into another. There were three fiberglass-chassied roadsters<br />

originally called <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2s (only later dubbed 2A by outsiders, when subsequent models appeared). After three<br />

highly successful SCCA seasons, 1963-65, two of those were given roofs and big-block Chevys to make them into 2D<br />

coupes for FIA endurance racing in 1966; a D won the 1000-K at Germany’s old Nurburgring. Then one of those Ds and<br />

the remaining 2(A) became 1967’s 2F coupes; one took victory at Brands Hatch in England. Three chassis, seven race cars.<br />

Rogers has now turned one of those Fs back into the “A” Hall drove at the BRIC; it happens to be the one that took the<br />

12 Hours of Sebring in that form in 1965. The remaining 2F, the Brands winner, was on display only. Similarly, a series<br />

of aluminum-monocoque sports racers began with 1965’s 2C. That was modified into the first 2E, the winged car that<br />

startled the world in the inaugural Can-Am season in 1966. The same chassis later became the big-block 2G for 1967<br />

and ’68. It was this in which Hall suffered a career-ending accident at a Las Vegas track called Stardust. Heavily<br />

damaged, that’s the one chassis that was finally scrapped, according to Rogers. “Jim couldn’t even look at a picture of it<br />

without getting the shakes.” The second 2E, winner of <strong>Chaparral</strong>’s only Can-Am victory (Laguna Seca, 1966), was at<br />

Road America and Hall briefly demonstrated that too. Totals: two more chassis, four more “cars.” Left home along with<br />

the restored 2D was the unloved 2H, 1969’s infamous “white whale” quasi-coupe, known fairly or not as Hall’s only<br />

failure. But present with honor was the <strong>2J</strong>, the notorious, controversial Ground Effects Vehicle, or Sucker Car, of 19<strong>70</strong>.<br />

That one worked so well it was promptly banned. The seventh <strong>Chaparral</strong> chassis, it was to be the last of the <strong>Chaparral</strong><br />

sports car line. Later there were some 2K single-seaters, which brought ground effects to Indianapolis and took the 500<br />

in 1980. Wait a minute—haven’t we left out a <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2B? Yes, there’s a car in Hall’s collection called that, but it isn’t<br />

really a <strong>Chaparral</strong>. It was built as a research project by Jim’s engineer friends in Chevy R&D. Tested extensively at<br />

Rattlesnake, it taught both parties a lot, and led to Hall’s choice of aluminum for the 2C chassis. This was only one<br />

example of the clandestine cooperation between <strong>Chaparral</strong> and Chevrolet. Another was the Sucker, which began life in<br />

Detroit as another Chevy experiment. Rogers has to patiently explain all this over and over. He too must be incredulous<br />

about the crowds clustering around the four plain white old cars he’s minding. For so long, they were so secret. For<br />

decades, the public rarely saw them. Hasn’t everybody forgotten? Not likely. True significance has a way of living on,<br />

and besides, this setting points out the magnitude of <strong>Chaparral</strong>’s accomplishments in its day. A featured race for vintage<br />

Can-Am cars has brought together a good sampling of Road Runner rivals—would-be rivals. The most casual look at<br />

them shows how conservative, how conventional, how pedestrian, were so many creative minds in the racing world<br />

outside Jim Hall’s fence. Many are good race cars, arguably even better race cars, because they won more races. But...<br />

But they don’t stand tall in the mind like the tall white Road Runners from the barren Texas plains.<br />

JIM HALL<br />

Born in Texas in 1935 and raised in Colorado and New Mexico, young Jim Hall was a student at the California Institute<br />

of Technology in Pasadena, Calif., when he started driving his brother's Austin Healey sports car at weekend road races<br />

in 1954. That led to the purchase of a state-of-the-art modified sports car from the best builders in the business in 1961,<br />

but the results didn't satisfy him. Hall set up his own race car building operation. Thus was born <strong>Chaparral</strong> Cars of<br />

Midland, Texas. During the years from 1963, when the first <strong>Chaparral</strong> 2 was built, to 19<strong>70</strong>, Hall's engineering genius<br />

with enthusiastic help from General Motors technicians turned out a series of dramatic race car inventions that have left<br />

a lasting impact on the sport of motor racing. First came the ultra-light chassis, which some called the all-plastic car, but<br />

which was a chassis built completely of reinforced fiberglass. Then Hall staggered his competition with a high-mounted<br />

wing that rode horizontal down the straightaways but was tilted down in the turns when the driver released a pedal,<br />

giving him extra downforce in the corners. That innovation was banned when the competition cried, "Unfair." What<br />

followed was the fixed wing, which became Hall's trademark. Today's winged race cars are the evolution of Hall's<br />

design statement. Hall had already introduced a competitive advantage so subtle that drivers didn't know what it was<br />

for half a season — an automatic transmission for road racing. With it, Hall and his team drivers could steer efficiently<br />

through corners without taking either hand off the wheel to shift gears. The most radical was yet to come — the<br />

"vacuum cleaner" <strong>Chaparral</strong> <strong>2J</strong>, described by one writer as looking like it was still in its packing case. Boxy in<br />

appearance, it sailed at incredible speeds through the corners, thanks to an auxiliary motor that created a vacuum under<br />

the car to increase traction. While it never won a race, it too was banned in response to competitive outcry. Hall,<br />

meanwhile, kept his best secrets to himself. He developed methods of testing at Rattlesnake Raceway that gave him data<br />

about what the car was doing at various sections of the track. By contrast, his competitors were satisfied with the lap<br />

times their stop watches were giving them. Working with Chevrolet engineers, Hall probably advanced the technology<br />

of racing more than any race car designer in that period. That may have been what prepared him for one of the most<br />

significant jumps in technology that Indy car developers have taken in the second half of this century —introduction of<br />

the Pennzoil <strong>Chaparral</strong>, Indy car racing's first "ground effects" car, in 1979. A year later his driver Johnny Rutherford<br />

won the Indy 500 and four other races, which combined with other top finishes gave him the first-ever combination of a<br />

CART PPG Cup IndyCar World Series championship and a U. S. Auto Club title. It also made Rutherford the consensus<br />

U. S. "driver of the year." Hall left Indy car racing in 1982 to concentrate on his other business interests but returned to<br />

the sport in 1991 with another bright yellow Pennzoil-sponsored car. Pennzoil persuaded Hall to return to Indy car<br />

racing after an absence of eight years. It began with a victory in the first race when John Andretti won for Jim Hall in<br />

Australia.

CHAPARRAL – RACE SUMMARY<br />

Date Circuit # Driver Qual Result<br />

12.07.<strong>70</strong> Watkins Glen, Rd3 66 Jackie Stewart 3. 1:03,690 DNF – 22 laps (brakes) (fastest lap 202,520 kph)<br />

13.09.<strong>70</strong> Road Atlanta, Rd7 66 Vic Elford 1. 1:17,420 6th – 69 laps (-6 laps)<br />

18.10.<strong>70</strong> Laguna Seca, Rd9 66 Vic Elford 1. 0:58,800 DNS – 0 laps (engine)<br />

01.11.<strong>70</strong> Riverside, Rd10 66 Vic Elford 1. 1:32,490 DNF – 2 laps (auxiliary engine)<br />

IMAGE GALLERY<br />

Vic Elford showing the prominent sucker fans at rear of the <strong>2J</strong>. <strong>Chaparral</strong> <strong>2J</strong> cockpit.<br />

Jim Hall trying his new <strong>Chaparral</strong> <strong>2J</strong>.<br />

SOURCES<br />

http://forums.atlasf1.com/showthread.php?s=&threadid=65933<br />

http://www.mulsannescorner.com/chaparral2j.html<br />

http://canam-at-lagunaseca.tripod.com/canam/chaparral/<br />

http://canam-at-lagunaseca.tripod.com/canam/articles/birth.htm<br />

http://www.ashcom.homestead.com/Elford<strong>2J</strong>.html<br />

http://www.vintagerpm.com/chaparral_history.htm<br />

http://www.sandcastlevi.com/racing/chaprral.htm<br />

http://autoweek.com/cat_print.mv?content_code=08539017<br />

http://perso.wanadoo.fr/buckhorn.wash/cars/archives/chaparral/chaparral.htm<br />

http://www.theautochannel.com/sports/pennrace/backhall.html<br />

© Compilation by Rainer Nyberg 2004-02-17 Fact-sheet 04/013