Aquatic Zoos - Captive Animals Protection Society

Aquatic Zoos - Captive Animals Protection Society

Aquatic Zoos - Captive Animals Protection Society

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

column shows the percentage of individual rays showing such behaviour in each particular public aquarium with respect to the total<br />

of individuals rays showing the behaviour, the seventh column shows the number of visible rays for each public aquarium, the<br />

eighth column shows the percentage of rays showing SBB with respect to the number of rays seen in each aquarium, and the<br />

remaining columns the same than columns five to eight but for rays of the genus Raja. The last row shows the values for all public<br />

aquaria put together.<br />

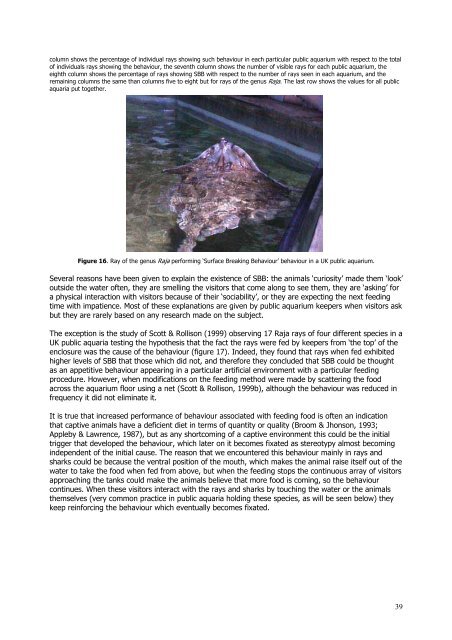

Figure 16. Ray of the genus Raja performing ‘Surface Breaking Behaviour’ behaviour in a UK public aquarium.<br />

Several reasons have been given to explain the existence of SBB: the animals ‘curiosity’ made them ‘look’<br />

outside the water often, they are smelling the visitors that come along to see them, they are ‘asking’ for<br />

a physical interaction with visitors because of their ‘sociability’, or they are expecting the next feeding<br />

time with impatience. Most of these explanations are given by public aquarium keepers when visitors ask<br />

but they are rarely based on any research made on the subject.<br />

The exception is the study of Scott & Rollison (1999) observing 17 Raja rays of four different species in a<br />

UK public aquaria testing the hypothesis that the fact the rays were fed by keepers from ‘the top’ of the<br />

enclosure was the cause of the behaviour (figure 17). Indeed, they found that rays when fed exhibited<br />

higher levels of SBB that those which did not, and therefore they concluded that SBB could be thought<br />

as an appetitive behaviour appearing in a particular artificial environment with a particular feeding<br />

procedure. However, when modifications on the feeding method were made by scattering the food<br />

across the aquarium floor using a net (Scott & Rollison, 1999b), although the behaviour was reduced in<br />

frequency it did not eliminate it.<br />

It is true that increased performance of behaviour associated with feeding food is often an indication<br />

that captive animals have a deficient diet in terms of quantity or quality (Broom & Jhonson, 1993;<br />

Appleby & Lawrence, 1987), but as any shortcoming of a captive environment this could be the initial<br />

trigger that developed the behaviour, which later on it becomes fixated as stereotypy almost becoming<br />

independent of the initial cause. The reason that we encountered this behaviour mainly in rays and<br />

sharks could be because the ventral position of the mouth, which makes the animal raise itself out of the<br />

water to take the food when fed from above, but when the feeding stops the continuous array of visitors<br />

approaching the tanks could make the animals believe that more food is coming, so the behaviour<br />

continues. When these visitors interact with the rays and sharks by touching the water or the animals<br />

themselves (very common practice in public aquaria holding these species, as will be seen below) they<br />

keep reinforcing the behaviour which eventually becomes fixated.<br />

39