The Qajar Epoch 1785-1925 - Memoirs of a Gay:sha

The Qajar Epoch 1785-1925 - Memoirs of a Gay:sha

The Qajar Epoch 1785-1925 - Memoirs of a Gay:sha

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

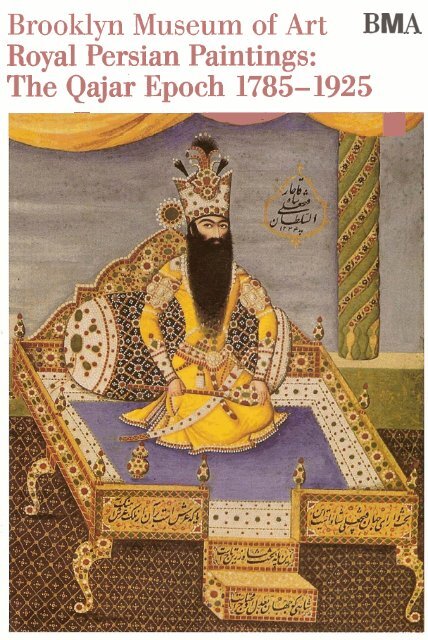

Brooldyn Museum <strong>of</strong> Art BMA<br />

Royal Persian Paintings:<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Qajar</strong> <strong>Epoch</strong> <strong>1785</strong>-<strong>1925</strong><br />

--<br />

I

Royal Persian Paintings: <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Qajar</strong> <strong>Epoch</strong> <strong>1785</strong>-<strong>1925</strong> is made<br />

possible in part by the National<br />

Endowment for the Humanities,<br />

as well as by Massoumi5 and<br />

Fereidoun Soudavar in memory<br />

<strong>of</strong> their sons Alireza and<br />

Mohammad. Major support is<br />

provided by <strong>The</strong> Hagop Kevorkian<br />

Fund, National Endowment for<br />

the Arts, <strong>The</strong> Rockefeller<br />

Foundation, the Family <strong>of</strong> the<br />

late Eskandar Aryeh, and Hashem<br />

Khosrovani. Additional support is<br />

provided by the Museum's Asian<br />

Art Council, Afsaneh Al-e<br />

Mohammad Dabashi, Mr. and<br />

Mrs. Dara Zargar, Elizabeth S.<br />

Ettinghausen, and the Patrons <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>Qajar</strong> Gala. An indemnity has<br />

been granted by the Federal<br />

Council on the Arts and the<br />

Humanities.<br />

Planning and research for the<br />

exhibition were supported by the<br />

National Endowment for the<br />

Humanities, <strong>The</strong> Hagop<br />

Kevorkian Fund, and the<br />

Mar<strong>sha</strong>ll and Marilyn R. Wolf<br />

Foundation. Funds for the cata-<br />

logue were provided through a<br />

publications endowment created<br />

by the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor<br />

Foundaiion and <strong>The</strong> Andrew W.<br />

Mellon Foundation.<br />

This gallery guide has been made<br />

possible by a gdt <strong>of</strong> Elizabeth S.<br />

Ettinghausen in memory <strong>of</strong><br />

Richard Ettinghausen.<br />

Above: Atlributed to Mirza Baba. Two<br />

Ifw.em Girls. Iran, circa 1811-14. Oil on<br />

canvas. Collection <strong>of</strong> the Royal Asiatic<br />

Society. London, 01.002<br />

,<br />

Brooklyn Museum <strong>of</strong> Art<br />

October 23,1998 January<br />

1 24,1999<br />

I<br />

Royal Persian Paintings: <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Qajar</strong> <strong>Epoch</strong> <strong>1785</strong>-<strong>1925</strong> is the first<br />

major museum exhibition to<br />

examine the visual arts <strong>of</strong> Iran's<br />

<strong>Qajar</strong> dynasty. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Qajar</strong> era fol-<br />

lowed the Safavid period, a golden<br />

age <strong>of</strong> Persian art and culture, and<br />

preceded the emergence <strong>of</strong> mod-<br />

em Iran. Under <strong>Qajar</strong> rule Iran<br />

was transformed from a tribal-<br />

based confederacy to a centralized<br />

monarchy <strong>sha</strong>ped by European<br />

influences. <strong>The</strong> rise <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Qajar</strong><br />

dynasty marked the beginning <strong>of</strong><br />

an era <strong>of</strong> relative political stability<br />

in which patronage <strong>of</strong> the arts<br />

flourished.<br />

<strong>The</strong> major artistic achievement <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>Qajar</strong> epoch was the flower-<br />

ing <strong>of</strong> a tradition <strong>of</strong> figural paint-<br />

ing rarely seen in the Islamic<br />

world. <strong>The</strong> wide use <strong>of</strong> the<br />

human figure in a variety <strong>of</strong><br />

media, in boih miniature and<br />

monumental scale, was an anom-<br />

aly in a culture that generally<br />

forbids human representation.<br />

In Iran, however, there was a her-<br />

itage <strong>of</strong> figural painting and sculp-<br />

ture associated with royalty dating<br />

back to antiquity. Although much<br />

<strong>of</strong> this legacy had been destroyed<br />

or driven underground with the<br />

Royal Perslan Palntlngs:<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Qajar</strong> <strong>Epoch</strong> 178!5-<strong>1925</strong><br />

advent <strong>of</strong> Islam in 641 A.D., the<br />

figural tradition continued in<br />

small-scale book illustration, met-<br />

alwork, and ceramics.<br />

During the <strong>Qajar</strong> regime, a long-<br />

dormant tradition <strong>of</strong> figural wall<br />

painting reemerged. Iran's interac-<br />

tion with the West also intensified,<br />

and <strong>Qajar</strong> painting was reinvigo-<br />

rated by European painting con-<br />

ventions. <strong>The</strong> major themes <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Qajar</strong> painting-royalty, women,<br />

and religious subjects-vividly<br />

reflect the critical political and<br />

social changes that occurred dur-<br />

ing the era.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Safavid Legacy<br />

<strong>The</strong> art and culture <strong>of</strong> <strong>Qajar</strong> Iran<br />

evolved as well from traditions<br />

established during the Safavid<br />

period (1501-1722), when inter-<br />

national trade, particularly the<br />

export <strong>of</strong> raw silk to Europe,<br />

brought great prosperity to Iran.<br />

Painting and architecture thrived<br />

under the Safavids.<br />

For centuries, elegantly copied<br />

and sumptuously illustrated<br />

Qur'ans and poetic manuscripts<br />

had been the principal channels<br />

<strong>of</strong> Persian artistic expression. <strong>The</strong><br />

manuscript pictured here (fig. 1)

embodies the features fundamen-<br />

tal to this style <strong>of</strong> art; it illus-<br />

trates a poetic subject (an episode<br />

from the Khamseh, or Quintet, <strong>of</strong><br />

the great Persian poet Nizami).<br />

Fig. 1: Artist unknown. Shirin<br />

Examines Khusraw's Portrait (detail).<br />

Detached folio from a manuscript <strong>of</strong><br />

theKhamseh <strong>of</strong> Nizami. Iran, late 15th<br />

century. Opaque watercolor, ink, mica,<br />

and gold on paper, mounted on board.<br />

S1986.140, Arthur M. SacWer Gallery,<br />

Smithsonian Institution, Smithsonian<br />

Unrestricted Trust hnds, Smithsonian<br />

Collection Acquisition Program, and Dr.<br />

Arthur M. Sackler<br />

Fig. 2: 'Ali Quli Bayg Jabbadar (active<br />

1657-1716). Presumed Portrait <strong>of</strong> Louis<br />

XIV in Anor. Isfahan, circa 1660-90.<br />

Opaque watercolors and gold-sprin-<br />

kling. MA2478, MusBe National des Arts<br />

Asiatiques-Guimet, Paris<br />

<strong>The</strong> artist has attempted not to<br />

represent the natural world but<br />

to convey an ideal world <strong>of</strong> beau-<br />

ty and luxury through vibrant<br />

color, harmonious composition,<br />

and two-dimensional space.<br />

By the seventeenth century, how-<br />

ever, Persian artists had begun to<br />

create single-page paintings that<br />

stand alone rather than illustrat-<br />

ing a text in a manuscript. This<br />

new mode <strong>of</strong> painting was influ-<br />

enced by the Western artworks<br />

<strong>of</strong>fered by European diplomats<br />

and traders to the Persian court.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Persian watercolor <strong>of</strong> Louis<br />

XIV illustrated here (fig. 2) uses.<br />

both European prints and<br />

European oil paintings as models.<br />

<strong>The</strong> artist, Xli Quli Bayg<br />

Jabbadar, has clearly mastered<br />

many European stylistic tech-<br />

niques: he creates a sense <strong>of</strong> deep<br />

space and uses modeling to make<br />

the figure look three-dimension-<br />

al. He also adopts the subtler,<br />

more naturalistic palette pre-<br />

ferred by European artists.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Qajar</strong> Era<br />

<strong>The</strong> Safavid dynasty came to a<br />

disastrous end in 1722, when<br />

Afghan tribes laid siege to the<br />

capital city, Isfahan, lulling<br />

eighty thousand people. In <strong>1785</strong>,<br />

after a long period <strong>of</strong> political<br />

unrest in which numerous tribal<br />

chiefs vied for power, the <strong>Qajar</strong>s,<br />

led by the relentless warlord Aqa<br />

Muhammad Khan <strong>Qajar</strong>,

emerged victorious. Having laid<br />

the foundation for a stable<br />

dynasty, Aqa Muhammad Khan<br />

passed the throne to his nephew,<br />

Fath 'Ali Shah (fig. 3), who<br />

reigned from 1798 to 1834.<br />

Fath 'Mi Shah presided over the<br />

flowering <strong>of</strong> <strong>Qajar</strong> visual arts. He<br />

commissioned life-size paintings<br />

in unprecedented numbers and<br />

ordered sun~ptuous court regalia<br />

embellished with figural and narrative<br />

scenes, such as the enameled<br />

gold dish shown here (fig. 4),<br />

adorned with the Persian royal<br />

insignia <strong>of</strong> the lion and sun.<br />

Perhaps more important, Fath<br />

'Ali Shah stabilized the empire<br />

and ensured the success <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Qajar</strong> dynasty by fathering some<br />

two hundred children, leaving<br />

behind a vast network <strong>of</strong> descen-<br />

dants to govern after his death.<br />

However, it was also during his<br />

reign that Iran found itself in a<br />

struggle with Russia over control<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Caucasus region. In two<br />

wars, Iran lost valuable territory<br />

along its norlhwest border. <strong>The</strong><br />

second war, ending in 1828, left<br />

the country almost bankrupt.<br />

Fig. 3: Mihr 'Ali (active 1790-1815).<br />

Portrait <strong>of</strong> Path Xli Shah Standing. Iran,<br />

dated A.II. 1224/~.u. 1809-10. Oil on<br />

canvas. VR-1107, State Hermitage<br />

Museum, Saint Petersburg<br />

That Irar- .--- .--anaged to maintain<br />

its identity even after its<br />

conquest by Muslim Arabs in the<br />

seventh century was partly owing<br />

to its long and revered history <strong>of</strong><br />

kingship, which extended back to<br />

antiquity. In his patronage <strong>of</strong><br />

court poetry and art, Fath 'Ali<br />

Shah invoked this tradition. He<br />

used the arts primarily as a<br />

means to convey his power, glorify<br />

the <strong>Qajar</strong> dynasty, and unify<br />

Iran.<br />

Early <strong>Qajar</strong> painting discarded<br />

European conventions and<br />

revived indigenous monumental<br />

painting and rock-carving tradi-<br />

Fig. 4: Muhammad Ja'far (active<br />

1800-1830). Dish with the Royal<br />

Iranian Emblem <strong>of</strong> the Lion and Sun.<br />

Tehran, dated A.H. 1233/~.~. 1817-18.<br />

Enameled gold. Courtesy <strong>of</strong> the Board<br />

<strong>of</strong> Trustees <strong>of</strong> the Victoria and Albert<br />

Museum, London

tions. In the portrait <strong>of</strong> Fath 'Ali<br />

Shah illustrated here (see again<br />

fig. 3), the rigid, hntal pose<br />

recalls ancient rock reliefs depicting<br />

pre-Islamic Pemian kings.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ruler's @~&sive 'exprwion<br />

and dazzling@$ however,<br />

reflect th@,awsional treatment<br />

<strong>of</strong> m&@$=~tdlustration<br />

enlarged to &'&&kk~<br />

Such works wem meant to<br />

impress Western monarchs with<br />

the opulence, and power <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Persian em~ire, and this portrait<br />

was probably commissioned as a<br />

gift for a Russian ruler. Fath 'Ali<br />

Shah's interest in participating in<br />

the produbtion <strong>of</strong> his image is<br />

revealed by an inscription in the<br />

lower left-hand corner which<br />

states that he inspected the<br />

painting in person during its production<br />

and approved it "without<br />

any changes."<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Qajar</strong>s believed that portraits<br />

could represent the ruler in an<br />

almost supernatural way. Portraits<br />

<strong>of</strong> Fath 'Ali Shah and his succes-<br />

sors were treated with the rever-<br />

ence accorded to the monarch<br />

himself when they were paraded<br />

in regional processionals and cer-<br />

emonies or presented as diplo-<br />

matic @.<br />

If Fath 'Ali Shah was the principal<br />

catalyst for the early, revival style<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Qajar</strong> painting, his grandson<br />

Nasir al-Din Shah, who reigned<br />

from1848 to1896, played an<br />

equally significant role in the evo-<br />

lution <strong>of</strong> Persian painting by act-<br />

ing as synthesizer and transmitter<br />

<strong>of</strong> European artistic traditions.<br />

Although Iran's reformers<br />

approached modern Western cul-<br />

ture with caution, fearful that the<br />

West's seductive material riches<br />

would lead to imperialistic inter-<br />

vention, under Nasir al-Din Shah<br />

Iran did adopt several Western<br />

innovations that directly affected<br />

the creation and dissemination <strong>of</strong><br />

art. <strong>The</strong> country's first institution<br />

<strong>of</strong> higher learning based on<br />

European models, the Dar al-<br />

Funun, trained artists in the e<br />

European academic tradition. <strong>The</strong><br />

lithographed newspaper provided<br />

a new forum for disseminating<br />

images. And as Iran embraced<br />

photography, artists began to use<br />

photographs as models for their<br />

paintings, making their works<br />

more lifelike. Invigorated by these<br />

innovations, <strong>Qajar</strong> painting<br />

reached its second florescence.<br />

Like his grandfather, Nasir al-Din<br />

Shah used art to disseminate his !<br />

dynastic image. <strong>The</strong> small-scale<br />

portrait illustrated here (fig. 5)<br />

reveals how he attempted to<br />

Fig. 5: Bahram Kirman<strong>sha</strong>hi (active<br />

1860s-1880s). Nasir &Din Shah Sated<br />

in a European Chak. Tehran,.dated A.H.<br />

1274/~.~. 1857. Oil on copper. MA0 776, - I<br />

Mw% du Louvre, Paris, section<br />

Islamique<br />

'

identify himself with both estab-<br />

lished cultural values and the<br />

currents <strong>of</strong> modernity. His regalia<br />

is as dazzling as Fath 'Ali Shah's,<br />

but his pose <strong>of</strong> casual elegance-<br />

he is seated on a European-style<br />

chair-is unprecedented for<br />

Persian royal imagery and reflects<br />

nineteenth-century European<br />

portrait conventions. <strong>The</strong> unusu-<br />

al medium <strong>of</strong> oil on copper cap-<br />

tures the luminosity and highly<br />

textured surface <strong>of</strong> European oil<br />

paintings.<br />

Ultimately, Nasir al-Din Shah's<br />

contacts with the West proved his<br />

downfall. By awarding lucrative<br />

commercial monopolies to foreign<br />

investors he sowed the seeds <strong>of</strong><br />

popular revolt. He was assassinat-<br />

ed by an antiroyalist activist in<br />

1896. At the turn <strong>of</strong> the twentieth<br />

century, the Iranian people began<br />

to oppose the <strong>Qajar</strong> monarchy.<br />

Several rulers followed each other<br />

quicldy as the dynasty began to<br />

crumble.<br />

<strong>The</strong> portrait illustrated here (fig.<br />

6) <strong>of</strong> Nasir al-Din Shah's son and<br />

successor, Muzaffar al-Din Shah,<br />

who reigned from 1896 to 1907,<br />

contrasts strikingly with earlier<br />

royal portraits. <strong>The</strong> artist has<br />

made no attempt to display the<br />

splendor <strong>of</strong> the ruler's court or<br />

accentuate the richness <strong>of</strong> his<br />

regalia. <strong>The</strong> <strong>sha</strong>h looks unhealthy<br />

and exhausted, standing only<br />

with the aid <strong>of</strong> a walking stick-.a<br />

sublle allusion perhaps to the frail<br />

state <strong>of</strong> the government during<br />

his rule. By the end <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Qajar</strong><br />

period, royal imagery had evolved<br />

from timeless, idealized icons to<br />

academic portraits influenced by<br />

European tradition.<br />

Fig. 6. 'Abd al-Husayn (Sani' Humayun)<br />

(1859-1921). Portrait <strong>of</strong> Muzaflar aal-Din<br />

Shah and Premier Xbd al-Majid Mirza,<br />

2yrn al-Dawleh. Tehran, early 20th cen-<br />

tury. Oil on canvas. Private collection<br />

Fig. 7. Attributed to Ahmad (active<br />

1820s-1830s). F mle Acrobat. Tehran,<br />

second or third quarter <strong>of</strong> the 19th an-<br />

tury. Oil on canvas. 719-1876, Lent by<br />

[lie Board <strong>of</strong> Trustees <strong>of</strong> the Victoria<br />

and Albert Museum, London

Representations <strong>of</strong> Women<br />

Traditionally, women in the<br />

Islamic world have rarely<br />

appeared in public unveiled.<br />

However, unveiled women were<br />

frequently depicted in Persian<br />

manuscript illustrations. During<br />

the early <strong>Qajar</strong> period, the con-<br />

text <strong>of</strong> paintings <strong>of</strong> women<br />

increasingly shifted from the pri-<br />

vate world <strong>of</strong> the manuscript to<br />

the public realm <strong>of</strong> palaces and<br />

pavilions. Decorum did not per-<br />

mit portraits <strong>of</strong> virtuous women<br />

or female members <strong>of</strong> the royal<br />

family to be displayed in public<br />

areas. <strong>The</strong>refore, the only repre-<br />

sentations <strong>of</strong> women deemed<br />

suitable were enlarged versions <strong>of</strong><br />

the idealized female types devel-<br />

oped for manuscript illustrations:<br />

women in European dress, musi-<br />

cians, dancers, and acrobats.<br />

Fernale representations such as<br />

the one pictured here (fig. 7)<br />

functioned as elements in the lav-<br />

ish decorative programs <strong>of</strong> the<br />

ruler's palace, little different from<br />

other royal accouterments.<br />

Late nineteenth-century painting<br />

conveys a very different image <strong>of</strong><br />

Persian women. In contrast to the<br />

entertainers and odalisques <strong>of</strong><br />

Fig. 8. Isn~a'il Jalayir (d. circa<br />

1868-1873). Lndies around a Samovar.<br />

Tehran, third quarter <strong>of</strong> the 19th century.<br />

Oil on canvas. P.56-1941, Victoria<br />

and Albert Museum, London<br />

earlier eras, the women in Ladies<br />

around a Samovar (fig. 8) are<br />

modestly clothed and covered in<br />

veils. <strong>The</strong> portrait <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Qajar</strong><br />

princess Taj al-Saltaneh<br />

(1884-1936) illustrated here (fig.<br />

9) reflects how women's roles and<br />

aspirations continued to change.<br />

Taj is depicted as a "modern"<br />

rincess. In fact, she was one <strong>of</strong><br />

he founding members <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Society for the Emancipation <strong>of</strong><br />

Women and the first Iranian<br />

woman to write her autobiogra-<br />

- phy, a work replete with insights<br />

into the plight <strong>of</strong> women living in<br />

the confines <strong>of</strong> the royal harem.<br />

Religious Imagery<br />

If Islamic culture generally<br />

approaches representations <strong>of</strong> the<br />

human figure with great caution,<br />

this is particularly true with<br />

regard to the painting <strong>of</strong> religious<br />

subjects. Nevertheless, a vigorous<br />

school <strong>of</strong> religious painting in a<br />

~o~ular . - fimral vernacular<br />

emerged i; Iran during the late<br />

nineteenth century.<br />

<strong>The</strong> development <strong>of</strong> religious<br />

l- painting coincided with-the popu-<br />

larization <strong>of</strong> the ta'zieh, a type <strong>of</strong><br />

passion play associated with the<br />

Muslim sect <strong>of</strong> Shi'ism, Iran's<br />

state religion since the sixteenth<br />

century. <strong>The</strong> ta'zieh relates the<br />

story <strong>of</strong> the Battle <strong>of</strong> Karbala, a<br />

tragedy at the heart <strong>of</strong> Shi'ite<br />

belief that commemorates the<br />

martyrdom <strong>of</strong> Imam Husayn (the<br />

third Shi'ite imam, or spiritual<br />

guide). Paintings <strong>of</strong> scenes from<br />

the narrative were nailed to the<br />

wall as backdrops to recitations <strong>of</strong><br />

the ta'zieh, and the narrator<br />

would point to each relevant event<br />

as he told the story. Significantly<br />

challenging Islamic views on fig-<br />

ural representation, these paint-<br />

ings reflect an innovative instance<br />

in the history <strong>of</strong> Persian painting<br />

in which religious subjects were<br />

produced and displayed for the<br />

public at large for the first time.<br />

Fig. 9. Artist unknown. Porh-ait <strong>of</strong><br />

Princess Taj al-Saltaneh (1884-1936)<br />

(detail) . Tehran, circa 1910. Oil on can-<br />

vas. Collection <strong>of</strong> Mohammad and<br />

Najmieh Batmanqlij, Washington, D.C.

--Csnhny<br />

Fueled by anti-imperialist senti-<br />

ments and frustration with the<br />

<strong>Qajar</strong> monarchy, which was<br />

viewed as corrupt and ineffective,<br />

the Iranian people revolted and<br />

established a parliament and<br />

new constitution in 1906. <strong>The</strong><br />

constitutional movement gave<br />

rise in the press to a lively tradi-<br />

tion <strong>of</strong> caricature, an art form<br />

diametrically opposed to the<br />

imperial grandeur <strong>of</strong> the painting<br />

<strong>of</strong> the early nineteenth century.<br />

<strong>The</strong> cartoon reproduced here (fig.<br />

10) communicates the nationalist<br />

Iranians' dramatic reaction to<br />

European imperialism and for-<br />

eign domination. It also illus-<br />

trates the ways in which Western<br />

technology was used to express<br />

anti-Western sentiments and pre-<br />

sents a fitting conclusion to an<br />

exhibition that charts the evolu-<br />

tion <strong>of</strong> <strong>Qajar</strong> painting from an<br />

indigenous art form to one that<br />

increasmgly reflected European<br />

conventions.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Qajar</strong>s had their final down-<br />

fall when Riza Khan, a military<br />

leader, deposed the last <strong>Qajar</strong><br />

ruler in 1921 and established the<br />

Pahlavi dynasty in <strong>1925</strong>. This<br />

dynasty endured until 1979,<br />

when it was overthrown by the<br />

Islamic movement led by<br />

Ayatollah Khomeini.<br />

Many <strong>of</strong> the artworks gathered<br />

together for Royal Persian<br />

Paintings were dispersed to<br />

Russia and Europe in the nine-<br />

teenth century. In reassembling<br />

them, the exhibition demon-<br />

strates the remarkable thematic<br />

range and visual splendor <strong>of</strong> an<br />

era <strong>of</strong> Persian painting that has<br />

long been neglected. Using the<br />

human figure as its central focus,<br />

Royal Persian Paintings illumi-<br />

nates the human face <strong>of</strong> a cul-<br />

ture that has-at least to the<br />

West-been concealed for the<br />

past two decades.<br />

Dr. Layla S. Diba<br />

Hagop Kevorkian Curator <strong>of</strong><br />

Islamic Art<br />

Pig 10: Mirza 'Ali. Asian Rulers<br />

Represented as Dogs (detail). From the<br />

newspaper Kashkul (Tehran), no. 29<br />

(1907). Lithograph. Princeton University<br />

Library, Princeton, New Jersey<br />

Right: Attributed to Abu '1 Hasan<br />

Ghaffari. Imam Quli Khan (detail).<br />

Tehran, circa 1855-66. Oil on canvas.<br />

Hashem Khosrovani <strong>Qajar</strong> Collection