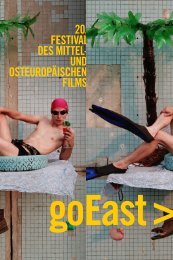

goEast_2024_Katalog

Sie wollen auch ein ePaper? Erhöhen Sie die Reichweite Ihrer Titel.

YUMPU macht aus Druck-PDFs automatisch weboptimierte ePaper, die Google liebt.

These sort of renegotiations and ambivalences can also

be found elsewhere in the region. Take the Soviet film

SEVERE YOUNG MAN / STROGIY YUNOSHA (1935), made

by Lithuanian director Abram Room in Ukraine after he

fell out of favour in Moscow. This film concerned with the

role of free love, love triangles and free will was eventually

banned when the work failed to be subsumed within the

ideals of Socialist Realism. Viewed from today’s vantage

point, the film is indeed queer in many ways, featuring

as it does classes, values and aesthetics that fall outside

of the norms of the time. Although the film’s characters

do discuss the moral values of communist societies, they

do so in saunas, in various states of undress, flexing their

muscular bodies while surrounded by antique statues.

Another Soviet Ukrainian production, DUBRAVKA (1967),

directed by Radomyr Vasylevskyi and based on the

eponymous story by Radiy Pogodin, depicts a teenage

tomboy with a “weird” name approaching adolescence

and developing her first crush – on a beautiful young

woman. While bravely courting “Rainbow” (as the tomboy

has nicknamed her crush), Dubravka grapples with her

growing awareness of gender expressions and roles,

among other things, finding herself alien to both the male

and female children surrounding her, “a cat that walks

by itself”. Sadly, the film is sanctimoniously infused with

more “heterodoomy” vibes than the original story, but it

still undoubtedly remains the queer darling of post-Soviet,

and especially Ukrainian film history. Symposium guests

Mariam Agamian and Olenka Syaivo Dmytryk will talk

about the queer readings of this film after its screening.

Regarding the film’s finale, they write: “Will the audience

believe in the closet and that gender and sexual roles are

played correctly? And did they believe it back in the 60s?

Or, on the contrary, did DUBRAVKA become an inspiration

and an example for a generation of tomboys, fairies,

Rainbows and tale-tellers?” (Syaivo and Agamian, 2022)

Uncovering and preserving forgotten queer pasts has long

been an urgent need of queer communities, and in recent

years it has become an important grassroots endeavour

throughout Central and Eastern Europe. We have invited

grassroots archivists, activists, researchers and curators

who act as memory agents, who are queering and diversifying

collective memories of (post-)socialist countries,

to talk about their experiences, goals and practices. The

archives that preserve often violently erased or invisible

traces of queerness in the regions are pivotal for reformulating

CEE pasts. But it is also crucial that the archival

materials circulate, as that is what creates memories, as

Dagmar Brunow (2019) writes. Anamarija Horvat makes

a similar point in her book Screening Queer Memory:

LGBTQ Pasts in Contemporary Film and Television,

arguing that film is an “affective memory resource”, as it

is a key element of the transmission of historical memory

for LGBTQ+ communities. Queer memory, she writes,

“is therefore a complex one, as it is impossible to

speak of LGBTQ people as a minority community

constructed in the same manner as either ethnic

or religious minority groups, though the queer community

will of course find itself formed across the

intersections of many such groups. In other words,

while the passage of memory in other minority

communities frequently occurs along familial

intergenerational lines, LGBTQ memory is more often

omitted from how families choose to narrate their

own past.” (2021, 4)

The Future

While curating this Symposium, it was sometimes

challenging to focus on thinking about queer cinema

and art when so many lives, including the lives of the

Symposium co-curator and participants from Ukraine

and Armenia, are often in direct danger for broader

reasons than sexuality and/or gender identity. On the

other hand, the Russian dictatorial regime is very vocal

about non-heteronormativity and gender expansiveness

being one of the pillars of the “Satanic West” that it wants

to devour. Although it is not easy to imagine a future when

one’s physical survival comes down to a matter of luck

during rocket attacks that occur on a regular basis, we are

making this effort as a gesture of our will to live – and

love – freely. However, the freedom of queer people of

Ukraine is not automatically guaranteed by the fall of the

empire that is actively trying to obliterate them (along

with their fellow citizens) at this very moment. Wars are

notorious for reinforcing divisions in societies: some lives

of queer Ukrainians are already more “grievable” (and

therefore deemed worthy of commemoration in cinema

and art) than others (Butler, 2009) – the lives of those

LGBT+ individuals fighting on the frontlines as part of the

Ukrainian Armed Forces – while many others, especially

transgender women and gender-expansive persons with a

“male” designation in their passports, are trying to navigate

the harsh reality of the martial law that prohibits them

from leaving the country as well as impending obligatory

mobilisation (among them, several potential, but sadly

absent guests of this Symposium). This is an extremely

volatile and challenging topic to discuss at this moment

in time, but it is also a perfect example for why exactly

it is important to continue conversations about the

future – despite all odds, despite the multiple man-made

tragedies erupting and unfolding in the modern world.

There is probably no more suitable place to have such

conversations than in the context of events dedicated to

queerness.

José Esteban Muñoz (2009, 1), when passionately writing

about queer utopian potential, claims that queerness is

“that thing that lets us feel that this world is not enough,

that indeed something is missing”, but also a “warm

illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality”. The

Symposium will ponder the utopian potential of (queer)

futures, expanding on the notion of queer imagination as

something broader than sexuality and gender identity. We

will think of what ‘queer’ means as a verb – a constant

questioning of hierarchies and power imbalances permeating

social and political structures, a tool for disrupting

them and at the same time for offering an alternative

imaginary. Muñoz argued that a queer idealism could

be not an abstract one, but instead must be political. We

have invited artists, activists, festival programmers and

filmmakers from Ukraine, Armenia and Kazakhstan to

talk about the potential of queer feminist thinking as a

tool for political transformation. Slovenian scholar Katja

Čičigoj will be musing on queer art’s potential to imagine

different, better and more just futures and societies in her

lecture Utopian Disidentifications: Pleasure, Critique and

the Future in Queer Art.

69 CINEMA ARCHIPELAGO: SYMPOSIUM