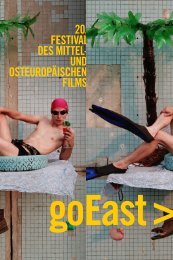

goEast_2024_Katalog

Sie wollen auch ein ePaper? Erhöhen Sie die Reichweite Ihrer Titel.

YUMPU macht aus Druck-PDFs automatisch weboptimierte ePaper, die Google liebt.

The Past

A special part of the Symposium that is also the result

of processing war trauma, still fresh and aching, is the

exhibition Political Textile by Ton Melnyk and Masha

Ravlyk, co-founders of ReSew sewing cooperative from

Ukraine, as well as artists and queer feminist activists.

The exhibition features a number of textile works created

using different techniques – sewing and application

from upcycled fabrics, embroidery and other methods –

reflecting on experiences of queer people from Ukraine

facing the existential horrors of the war. The central

piece of the exhibition comprises three anti-war banners,

as an homage to Maria Prymachenko, a self-taught

Ukrainian artist who lived in the 20th century and whose

works, created in a range of media (paintings, ceramics,

embroidery), have often been referred to as “naïve” in

terms of their style. Many of Prymachenko’s works were

the artist’s reaction to her personal experience of World

War II. Ton Melnyk and Masha Ravlyk write about the

process of creating these homages: “While working on the

banners, we felt the war at a new level. Now having our

own experience, we were wondering how Prymachenko

accurately noticed and depicted the horror, anxiety, and

consequences of the war in her own way. We noticed that

manual sewing work has a therapeutic effect.”

It was important to us that the Symposium not only

feature works directly connected with non-normative

sexualities and/or gender identities – in addition, it

should also feature those contemporary experiences of

queer people from the region that are most relevant today.

These erasures and violence in the regions featured in

the Symposium were often reflected on film in complex

ways, leaving the grim impression that there is little

space beyond the boundaries of heteronormativity and

patriarchy, little hope of a queer life and future. But the

curated short-film programs show that all is not grim, far

from it in fact: luckily, queerness is nothing if not resilient.

In recent years, one of the most exciting fields for CEE film

creativity and images of queerness has been the shortfilm

form. Shorts, made with no or very small budgets

and often within webs of transnational cooperation

between younger filmmakers, reveal a diverse array of

cinematic visions, aesthetics and themes: from no-budget

DIY productions and experimental works to animations

and visually slick films, these works manage to queer the

visual landscape of these once painfully heteropatriarchal

regions. Sometimes they do still talk about sadness and

heartbreak, but queerness is also so much more. It is

solidarity, joy, playfulness, fantasy, anger, survival and

revolt.

Delving into the past of queer representation in CEE is

challenging – not because queer images did not exist,

but because they are acutely under-researched, even

among CEE scholars. Featured Symposium guest Nebojša

Jovanović wrote about this “social amnesia” and its

consequences: “Despite some precious exceptions […],

we generally persist in reluctance to foreground queer

experiences during socialism, thus obliterating them

more fully than any homophobia or criminalization of

homosexuality in the socialist countries could do” (2012:

212).

Contrary to commonly-held beliefs and old stereotypes,

non-heteronormativity and LGBT+ cinematic images

have always been a part of the vastly different CEE film

landscapes. Sometimes subtle, at other times explicit or

even radical, these images disrupted heteronormative

societies and constructed complex on-screen sexualities

and gender expressions. In the Symposium film program,

rarely-seen queer images from the past will be screened

and (re-)contextualised through lectures and talks

in order to destabilise the idea of a homophobic past

followed by a more liberal attitude towards queerness

in the post-transition period. That is not to say that

past public discourse on LGBT+ issues in CEE countries

was not riddled with stereotypes, violent homophobia,

censorship and discrimination, but it is important to

point out that queer images did exist in CEE, though often

in an ambiguous relation to public attitudes regarding

homosexuality.

Take for example FIVE MINUTES OF PARADISE / PET

MINUT RAJA (1959): when Slovenian director Igor Pretnar

was unable to secure funding for his first feature in his

home country, he went to Bosna Film, where he realised

his story about two concentration camp prisoners that

get sent to a German officer’s house to disarm a bomb.

Since it is a suicide mission, their guards leave them to it,

and the men, who have very little hope of surviving, take

the opportunity to dress up, smoke, drink and dream of

freedom. The 1950s were a prolific decade for Yugoslav

queer imagery, which was framed within the masculine

collectives featured in socialist realist films. These

films not only blurred the lines between homosocial and

queer – they also gave Yugoslavs their first images of

cross-dressing and non-closeted gays. Jovanović notes

that these films destabilise “the totalitarian-model view

of the socialist past”, which sees film and art as totally

suppressed by the regimes’ ideology and propaganda.

Instead of the idea of top-down homophobia, he proposes

that queerness was “constantly redefined, discussed and

valued at different social sites and by many social agents

in early Yugoslav socialism”. (Jovanović, 2016: 132-133)

68