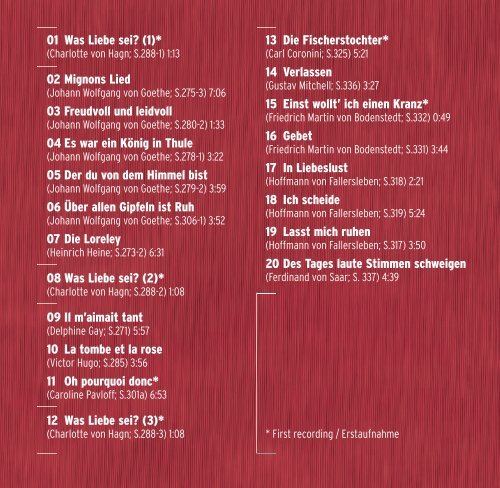

01 was Liebe sei? (1)* 02 mignons Lied 03 Freudvoll und leidvoll 04 ...

01 was Liebe sei? (1)* 02 mignons Lied 03 Freudvoll und leidvoll 04 ...

01 was Liebe sei? (1)* 02 mignons Lied 03 Freudvoll und leidvoll 04 ...

Sie wollen auch ein ePaper? Erhöhen Sie die Reichweite Ihrer Titel.

YUMPU macht aus Druck-PDFs automatisch weboptimierte ePaper, die Google liebt.

<strong>01</strong> <strong>was</strong> <strong>Liebe</strong> <strong>sei</strong> (1)*<br />

(Charlotte von Hagn; S.288-1) 1:13<br />

<strong>02</strong> <strong>mignons</strong> <strong>Lied</strong><br />

(Johann Wolfgang von Goethe; S.275-3) 7:06<br />

<strong>03</strong> <strong>Freudvoll</strong> <strong>und</strong> <strong>leidvoll</strong><br />

(Johann Wolfgang von Goethe; S.280-2) 1:33<br />

<strong>04</strong> Es war ein König in Thule<br />

(Johann Wolfgang von Goethe; S.278-1) 3:22<br />

05 Der du von dem Himmel bist<br />

(Johann Wolfgang von Goethe; S.279-2) 3:59<br />

06 Über allen Gipfeln ist Ruh<br />

(Johann Wolfgang von Goethe; S.306-1) 3:52<br />

07 Die Loreley<br />

(Heinrich Heine; S.273-2) 6:31<br />

08 <strong>was</strong> <strong>Liebe</strong> <strong>sei</strong> (2)*<br />

(Charlotte von Hagn; S.288-2) 1:08<br />

13 Die Fischerstochter*<br />

(Carl Coronini; S.325) 5:21<br />

14 Verlassen<br />

(Gustav Mitchell; S.336) 3:27<br />

15 Einst wollt’ ich einen Kranz*<br />

(Friedrich Martin von Bodenstedt; S.332) 0:49<br />

16 Gebet<br />

(Friedrich Martin von Bodenstedt; S.331) 3:44<br />

17 In <strong>Liebe</strong>slust<br />

(Hoffmann von Fallersleben; S.318) 2:21<br />

18 Ich scheide<br />

(Hoffmann von Fallersleben; S.319) 5:24<br />

19 Lasst mich ruhen<br />

(Hoffmann von Fallersleben; S.317) 3:50<br />

20 Des Tages laute Stimmen schweigen<br />

(Ferdinand von Saar; S. 337) 4:39<br />

09 Il m’aimait tant<br />

(Delphine Gay; S.271) 5:57<br />

10 La tombe et la rose<br />

(Victor Hugo; S.285) 3:56<br />

11 Oh pourquoi donc*<br />

(Caroline Pavloff; S.3<strong>01</strong>a) 6:53<br />

12 <strong>was</strong> <strong>Liebe</strong> <strong>sei</strong> (3)*<br />

(Charlotte von Hagn; S.288-3) 1:08<br />

* First recording / Erstaufnahme

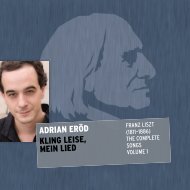

FRANZ LISZT<br />

In view of the forthcoming 200th birthday of Franz Liszt in 2<strong>01</strong>1, the participants in the Liszt <strong>Lied</strong> Edition<br />

consider it necessary to ensure that the composer’s <strong>Lied</strong>er sets are given their due place in the canon.<br />

In order to give both listeners and active musicians unrestricted access to Liszt’s <strong>Lied</strong> repertoire, we<br />

also intend to make available previously unpublished works and to present recording premiers.<br />

While Liszt’s instrumental pieces in their totality may certainly be difficult to comprehend and appreciate,<br />

this is true even more so for his <strong>Lied</strong>er sets and his religious vocal compositions: even today, Liszt’s<br />

reputation too often is considered to be that of an<br />

important virtuoso pianist and creator of monumental<br />

symphonic epics.<br />

In fact, however, Liszt’s <strong>Lied</strong>er contain the essence<br />

of his entire oeuvre and cannot be ignored in examining<br />

the developmental process of this composer.<br />

Many of his musical ideas sprang originally from<br />

the <strong>Lied</strong> repertoire, since song can be the simplest<br />

expression of programmatic thinking as well as part<br />

of a dramatic treatment. The <strong>Lied</strong>er are often the<br />

direct expression of the composer’s personality and<br />

touch upon all aspects of his life – from casual<br />

songs to those that disclose Liszt’s most inner feelings<br />

as an artist, a person, a devout Catholic, and a<br />

patriot.<br />

The different versions of individual works reflect<br />

not only the artist’s personal development but also<br />

Franz Liszt um 1835<br />

that of his compositions as well. The unique aspect<br />

of the <strong>Lied</strong> repertoire thus lies in the diversity

THE SONG<br />

„The new artistic ideal proclaimed by Liszt <strong>was</strong> aimed at a synthesis of music and poetry, at a new<br />

musical language having ‚expressive certainty‘ as one of its core precepts, and not least at a new perspective<br />

on the genre,“ wrote Detlef Altenburg with respect to the phenomenon of the so-called New<br />

German School. 1 Indeed: During his Weimar period, Liszt sought to unify music and literature in an<br />

unconventional manner – <strong>und</strong>er the framework of a new genre of symphonic epic. As he himself (or<br />

perhaps his famulus) put it: „Music has been connected with literary or quasi-literary works through<br />

the sung word since time immemorial; now, the goal is to unify the two in a manner more intimate<br />

than has thus far been the case. Music is increasingly assimilating the masterpieces of literature in its<br />

own masterpieces.“ 2<br />

In the songs of Franz Schubert, Liszt could find examples of a novel, intimate nexus between poetry<br />

and music; and find them he did, as is made evident by the virtuoso pianist‘s numerous Schubert transcriptions.<br />

3 With a symphonic epic, however, the nature of the relationship between music and literature<br />

is different than with a song or an opera: It does not involve the mere scoring of a presented text,<br />

as is the case in the latter two instances. This makes it all the more surprising that Liszt, the composer<br />

of programmatic instrumental pieces, wrote so many songs, i.e., provided so many examples of the<br />

more traditional coupling of music and literature. But do Liszt‘s <strong>Lied</strong>er serve to document his literary<br />

interests And are they „true“ songs<br />

Although Liszt scored poems of high literary repute (e.g., poems by Goethe, Schiller, Heine, Hugo or<br />

Petrarch), it is striking how many of the texts he chose to score are NOT literary masterpieces. Many<br />

of his <strong>Lied</strong>er are chance compositions: The lyrics to „Was <strong>Liebe</strong> <strong>sei</strong>,“ for instance, came from the celebrated<br />

actress Charlotte von Hagn, with whom Liszt had an intimate relationship in the early 1840s.<br />

It should also be pointed out that Liszt‘s vocal compositions – with respect to the manner in which<br />

they have been scored – often do not fit well within the genre of song but rather within that of opera.<br />

Pieces that have repetitive lyrics and operatic codas, such as „Die Loreley“ or „Kennst du das Land,“<br />

are representative of the type of aria in which „music ... is merely a vehicle for an otherwise largely

Aux accents du rossignol<br />

Sous la floraison pleinement<br />

épnouie de la frondaison.<br />

Longuement!<br />

20 Des Tages laute<br />

Stimmen schweigen<br />

(Ferdinand von Saar)<br />

Des Tages laute Stimmen<br />

schweigen,<br />

Und dunkeln will es allgemach,<br />

Ein letztes Schimmern<br />

in den Zweigen,<br />

Dann zieht auch dies<br />

der Sonne nach.<br />

Noch leuchten ihre Purpurgluten<br />

Um jene Höhen, kahl <strong>und</strong> fern,<br />

Doch in des Äthers klaren Fluten<br />

Erzittert schon ein blasser Stern.<br />

Ihr müden Seelen rings im Kreise,<br />

So ist euch wieder Ruh gebracht;<br />

Aufatmen hör ich euch noch leise,<br />

Dann küsst euch still<br />

<strong>und</strong> mild die Nacht.<br />

The day‘s loud voices fall silent,<br />

And darkness gradually spreads;<br />

A last shimmer in the branches,<br />

Then this too follows the sun.<br />

Its purple glow still illumines<br />

Those heights, bare and distant,<br />

Yet in the clear ocean of space<br />

Already a pale star trembles.<br />

Ye weary souls all aro<strong>und</strong>,<br />

Thus is peace brought<br />

to you again;<br />

I hear you still breathing soft<br />

and deep,<br />

Then night kisses you quietly<br />

and gently<br />

Les voix bruyantes du jour<br />

se taisent<br />

Et peu à peu la nuit tombe,<br />

Une derniére lueur dans les<br />

frondaisons<br />

Puis celle-ci se retire aussi<br />

dans le sillage du soleil.<br />

Ses rayons de pourpre<br />

resplendissent encore<br />

Autour de ces cimes dépouillées<br />

et lointaines,<br />

Mais dans les claires ondes<br />

de l‘éther<br />

Tremble déjà une pâle étoile.<br />

A vous, âmes lasses tout alentour,<br />

Le rpos est ainsi rendu,<br />

Je vous entends encore<br />

respirer tout bas,<br />

Puis la nuit appose sur vous<br />

son silencieux et doux baiser.

Janina Baechle And Charles Spencer<br />

After a few years only Janina Baechle has become one of the great mezzo-sopranos of our time. Born<br />

in Hamburg, she studied musicology and history in her home town. Simultaneously she took singing<br />

lessons with Gisela Litz and later finished her vocal education with Brigitte Fassbaender. Her first public<br />

performance <strong>was</strong> in 1997. Since 20<strong>04</strong> she is a member of the Vienna State Opera, indispensable in<br />

the roles of Ortrud, Brangäne and Quickly. On other opera stages she could be seen and heard as the<br />

nurse in „The Woman Without a Shadow“ or Amneris in „Aida“, the last being her most frequently<br />

sung part. However, Janina Baechle has always had a strong inclination to do concerts. In recent<br />

years, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra have invited her to sing in Mahler‘s 2nd Symphony (<strong>und</strong>er<br />

Seiji Ozawa) and „The Song of the Earth“ (<strong>und</strong>er Kent Nagano). Many listeners were surprised to hear<br />

that this voice, fit for the great Wagner parts, <strong>was</strong> also able to master a most tender pianissimo. Tiana<br />

Lemnitz <strong>was</strong> also known for her „piano“ singing once (she <strong>was</strong> called „Piana“ in Berlin), yet she „<strong>was</strong>“<br />

Elsa, not Ortrud. Since graduation Janina Baechle has been touring from recital to recital presenting<br />

the most astonishing programs – in German, English, French, Italian or Russian. Of course she feels<br />

comfortable with Brahms, Wolf and Mahler whom she appreciates in particular. At present she feels<br />

also a strong affinity to the French repertoire and the French language which she speaks better than<br />

most people in France. An important moment in her life <strong>was</strong> when she met Charles Spencer, the<br />

favorite accompanist of singer Christa Ludwig most of whose parts at the State Opera were passed on<br />

to Janina. Born in England, Charles Spencer has studied in London and Vienna. He <strong>was</strong> Christa Ludwig‘s<br />

accompanist for 12 years until her good-bye tour in 1993. He also worked with June Anderson,<br />

G<strong>und</strong>ula Janowitz, Marjana Lipovsek, Jessye Norman and Thomas Quasthoff.

Doubt shall shy away<br />

from my breast,<br />

leave it like a burden does.<br />

Anew I weep, anew I live,<br />

I start to feel so light.<br />

17 In <strong>Liebe</strong>slust<br />

(Hoffmann von Fallersleben)<br />

In <strong>Liebe</strong>slust, in Sehnsuchtsqual,<br />

O höre mich!<br />

Eins sing‘ ich nur viel tausendmal<br />

Und nur für dich!<br />

Ich sing es laut durch Wald<br />

<strong>und</strong> Feld,<br />

O höre mich!<br />

Ich sing es durch die ganze Welt:<br />

Ich liebe dich!<br />

Und träumend noch in stiller Nacht<br />

Muss singen ich,<br />

Ich singe, wenn mein Aug‘ erwacht:<br />

Ich liebe dich!<br />

Und wenn mein Herz<br />

im Tode bricht,<br />

O sähst du mich!<br />

Du sähst, dass noch<br />

mein Auge spricht:<br />

Ich liebe dich!<br />

In love’s delight and torments<br />

of loving,<br />

Oh, listen to me!<br />

One song I sing a thousand times<br />

and only for you<br />

I sing it aloud through forest<br />

and fields,<br />

Oh, listen to me!<br />

I sing it throughout<br />

the whole world:<br />

I love you!<br />

And dreaming through<br />

the quiet night<br />

I have to sing,<br />

I sing when my eyes open:<br />

I love you!<br />

And when my heart breaks death,<br />

Oh, look at me!<br />

You see that my eyes still speak:<br />

I love you!<br />

Dans l‘ivresse de l‘amour, dans le<br />

tourmant du désir,<br />

O! écoute-moi!<br />

Il y a quelque chose que je ne<br />

chante que des milliers et des<br />

milliers de fois<br />

Et que pour toi seule!<br />

Je le clame bien haut à travers les<br />

bois et les champs,<br />

O! écoute-moi!<br />

Je le chante à travers le monde<br />

entier:<br />

Je t‘aime!<br />

Et rêvant encore dans la nuit<br />

silencieuse<br />

il me faut chanter,<br />

Je chante dès que mon œil<br />

s‘éveille:<br />

Je t‘aime!<br />

Et lorsque mon cœur s‘anéantira<br />

dans la mort,<br />

O! puisses-tu alors me voir!<br />

Tu verrais que mes yeux te disent<br />

encore:<br />

Je t‘aime!<br />

18 Ich scheide<br />

(Hoffmann von Fallersleben)<br />

Die duftenden Kräuter auf der Au‘<br />

der Halm im frischen Morgenthau<br />

die Bäum‘ im grünen Kleide,<br />

ein jedes ruft: ich scheide,<br />

leb‘ wohl, ich scheide.<br />

Die Rosen in ihrer frischen Pracht,<br />

die Lilien in ihrer Engelstracht,<br />

die Blümchen auf der Heide,<br />

ein jedes ruft: ich scheide!<br />

leb‘ wohl, ich scheide!<br />

Ist Alles nur ein Kommen<br />

<strong>und</strong> Gehen,<br />

ein Scheiden mehr als Wiedersehn,<br />

wir freu‘n uns, hoffen <strong>und</strong> leiden

FRANZ LISZT<br />

Anlässlich des 200. Geburtstags von Franz Liszt im Jahr 2<strong>01</strong>1 ist es den Beteiligten der Liszt-<strong>Lied</strong>-Edition<br />

ein Bedürfnis, dem <strong>Lied</strong>schaffen des Komponisten den ihm gebührenden Platz in der Rezeption zu<br />

sichern. Um sowohl dem Hörer als auch dem aktiven Musiker einen uneingeschränkten Zugang zu Liszts<br />

<strong>Lied</strong>repertoire zu ermöglichen, wollen wir auch unveröffentlichte Werke publizieren <strong>und</strong> <strong>Lied</strong>er in<br />

Ersteinspielung präsentieren.<br />

Ist das Instrumentalwerk Liszts in <strong>sei</strong>ner Gesamtheit bereits nur schwer zu erfassen <strong>und</strong> zu erfahren, so<br />

gilt das noch in viel größerem Maße für <strong>sei</strong>n <strong>Lied</strong>schaffen <strong>und</strong> <strong>sei</strong>ne geistlichen Vokalkompositionen: Zu<br />

sehr eilt Liszt immer noch <strong>sei</strong>n Ruf als bedeutender Klaviervirtuose<br />

<strong>und</strong> als Schöpfer gigantischer Symphonischer Dichtungen<br />

voraus.<br />

Franz Liszt im März 1886<br />

Tatsächlich aber tragen Liszts <strong>Lied</strong>er <strong>sei</strong>nen gesamten Schaffenskosmos<br />

auf besondere Weise mit <strong>und</strong> sind aus dem Entwicklungsprozess<br />

dieses Komponisten nicht wegzudenken.<br />

Viele <strong>sei</strong>ner musikalischen Ideen stammen ursprünglich aus<br />

dem <strong>Lied</strong>repertoire. Denn das <strong>Lied</strong> kann der einfachste Ausdruck<br />

eines programmatischen Gedankens <strong>sei</strong>n oder Teil einer<br />

dramatischen Handlung. Die <strong>Lied</strong>er sind oft der unmittelbare<br />

Ausdruck der Persönlichkeit des Komponisten <strong>und</strong> berühren<br />

alle Bereiche <strong>sei</strong>nes Lebens – das reicht vom Gelegenheitslied<br />

bis hin zu den <strong>Lied</strong>ern, die Liszts innere Befindlichkeit als Künstler,<br />

Mensch, gläubiger Katholik <strong>und</strong> Patriot verraten.<br />

Die verschiedenen Fassungen der einzelnen Werke spiegeln<br />

aber nicht nur die persönliche, sondern auch die kompositorische<br />

Entwicklung des Künstlers wider. Das Besondere des<br />

<strong>Lied</strong>repertoires liegt daher in der Verschiedenheit, aus wel-

Oh! why if on their roads<br />

The sweet joys are not missing,<br />

why then do all of them cry,<br />

Those poor women here on earth<br />

Do not throw on this mystery<br />

Your disdain, cold and cruel,<br />

And just for the laughter<br />

of the earth<br />

Do not sneer at the tears<br />

from heaven.<br />

13 Die Fischerstochter<br />

(Carl Coronini)<br />

Die Fischerstochter<br />

sitzt am Strand,<br />

es liegt das Netz ihr in der Hand,<br />

der Blick schweift hin ins Weite.<br />

„O Schwalbe, ziehe,<br />

zieh‘ geschwind,<br />

du bist ja schneller als der Wind,<br />

geleite ihn, geleite.“<br />

Der Schiffsjung‘<br />

steht am Mast gelehnt,<br />

<strong>sei</strong>n Herze schlägt,<br />

<strong>sei</strong>n Herze sehnt<br />

sich an das Land zurücke;<br />

<strong>und</strong> eine helle Träne hängt,<br />

vom bittern Herzeleid getränkt,<br />

an <strong>sei</strong>nem trüben Blicke.<br />

„O treue Möwe, eil‘ zu ihr,<br />

erzähl‘, erzähle ihr von mir,<br />

ihr <strong>sei</strong>d ja schnell wie Blitze.<br />

Sag‘ ihr, ich <strong>sei</strong> in Gottes Hand,<br />

<strong>und</strong> baue dir ein Nest am Strand.<br />

Bewahre sie, bewahre.“<br />

Am Himmel eine Wolke zog,<br />

die Schwalbe schoß, die Möwe flog,<br />

den Auftrag zu bestellen.<br />

Die Wolke wurde zum Orkan,<br />

das Schiff verschlang der Ozean,<br />

Erzählt es nicht, ihr Wellen!<br />

Doch <strong>was</strong> die Welle nicht erzählt,<br />

das bleibt ihr ewig nicht verhehlt,<br />

die Ahnung hat gesprochen.<br />

Und wenn das Auge tränenleer,<br />

dann wird das Leben gar zu schwer,<br />

das Herze ist gebrochen.<br />

The fisher’s daughter<br />

sits on the beach,<br />

holding the net in her hand,<br />

her look roaming into the distance.<br />

“Oh, swallow, fly! Fly quickly<br />

for you are faster than the wind,<br />

escort him, do escort!”<br />

The ship’s boy leans<br />

against the mast<br />

his heart beats heavily,<br />

longing back to the land.<br />

Watered by a bitter pain<br />

in his heart,<br />

a pale tear hangs<br />

in his gloomy look.<br />

“Oh, true seagull, hurry,<br />

tell, tell her about me<br />

for you are fast like lighnings are.<br />

Tell her that I’m in God’s own hand,<br />

then build a nest on the beach<br />

and guard her, guard her!”<br />

A cloud moved in the sky,<br />

the swallow rushed,<br />

the seagull flew<br />

to fulfill their orders.<br />

The cloud grew into a storm,<br />

and the sea engulfed the ship.<br />

Don’t tell it, waves!<br />

Although not told by the wave,<br />

it remained no secret to her<br />

when she listened to her feeling.<br />

If the eye has no tears<br />

life gets too hard.<br />

Her heart is broken.

DAS LIED<br />

Das von Liszt „proklamierte neue Kunstideal zielte auf eine Synthese von Musik <strong>und</strong> Dichtung, auf eine<br />

neue Musiksprache, für die eine der obersten Maximen die ,sprechende Bestimmtheit‘ ist, <strong>und</strong> nicht zuletzt<br />

ein neues Gattungsdenken“, schreibt Detlef Altenburg im Zusammenhang mit dem Phänomen der so<br />

genannten „Neudeutschen Schule“. 1 Wahrhaftig: Liszt wollte während <strong>sei</strong>ner Weimar-Periode Musik <strong>und</strong><br />

Literatur in einer unkonventionellen Weise vereinigen: im Rahmen einer neuen Gattung der symphonischen<br />

Dichtung. Wie er selbst (oder vielleicht <strong>sei</strong>n Famulus) es formulierte: „Durch das gesungene Wort<br />

hat von jeher eine Verbindung der Musik mit literarischen oder quasi literarischen Werken bestanden;<br />

gegenwärtig wird nun eine Vereinigung Beider erstrebt, die eine innigere zu werden verspricht, als sie<br />

bis jetzt vorgekommen. Die Musik nimmt in ihren Meisterwerken mehr <strong>und</strong> mehr die Meisterwerke der<br />

Literatur in sich auf.“ 2<br />

Beispiele für eine neuartige, innige Verbindung von Dichtung <strong>und</strong> Musik konnte Liszt in den <strong>Lied</strong>ern von<br />

Franz Schubert finden; <strong>und</strong> er hat sie auch gef<strong>und</strong>en, wie die zahlreichen Schubert-Transkriptionen des<br />

Klaviervirtuosen zeigen. 3 Die Beziehung von Musik <strong>und</strong> Literatur ist aber in einer symphonischen Dichtung<br />

von anderer Art als in einem <strong>Lied</strong> oder einer Oper: Es handelt sich nicht um die bloße Vertonung einer<br />

gegebenen Textvorlage wie in den letzteren Fällen. Da ist es um so mehr überraschend, dass Liszt, der<br />

Komponist programmatischer Instrumentalwerke, so viele <strong>Lied</strong>er in Musik setzte, das heißt, so viele Beispiele<br />

für die traditionellere Verbindung von Musik <strong>und</strong> Literatur lieferte. Sind aber die Lisztschen <strong>Lied</strong>er<br />

Dokumente <strong>sei</strong>ner literarischer Interessen Und sind sie „wahre“ <strong>Lied</strong>er<br />

Obwohl Liszt auch Gedichte von hohem literarischem Wert vertonte (z.B. Dichtungen von Goethe, Schiller,<br />

Heine, Hugo oder Petrarca), ist es auffallend, wie oft die von ihm zur Vertonung ausgewählten Texte NICHT<br />

zu den Meisterwerken der Literatur gehören. Viele <strong>sei</strong>ner <strong>Lied</strong>er sind Gelegenheitskompositionen: Der Text<br />

von „Was <strong>Liebe</strong> <strong>sei</strong>“ stammt z.B. von der gefeierten Schauspielerin Charlotte von Hagn, zu der Liszt Anfang<br />

der 1840er-Jahre eine innige Bekanntschaft pflegte.<br />

Es muss auch bemerkt werden, dass die Lisztsche Vokalkompositionen – <strong>was</strong> die Art <strong>und</strong> Weise der Vertonung<br />

betrifft – oft nicht der Gattung <strong>Lied</strong>, sondern eher der Oper nahestehen. Werke mit vielen Textwieder-

Dans la lueur du soleil couchant.<br />

La plus belle des filles est assise<br />

Là-haut, splendide,<br />

Ses bijoux d‘or flamboient,<br />

Elle peigne ses cheveux d‘or.<br />

Elle les coiffe avec un peigne d‘or<br />

Tout en chantant une chanson<br />

Qui possède une étrange<br />

Et violente mélodie.<br />

Le batelier dans son petit esquif<br />

En est étreint d‘une douleur<br />

sauvage,<br />

Il ne regarde pas le récif,<br />

Il ne regarde que vers les hauteurs.<br />

Je crois qu‘à la fin les vagues<br />

Ont englouti le batelier et sa<br />

barque;<br />

Et c‘est avec son chant<br />

Que l‘a fait la Lorelei.<br />

09 Il m‘aimait tant<br />

(Delphine Gay)<br />

Non, je ne l‘aimes pas;<br />

mais de bonheur émue,<br />

Ma sœur, je me sentais rougir<br />

en l‘écoutant;<br />

Je fuyais son regard,<br />

je tremblais à sa vue:<br />

Il m‘aimait tant!<br />

Je me parais pour lui,<br />

car je savais lui plaire;<br />

Pour lui, j‘ai mis ces fleurs<br />

et ce voile flottant:<br />

Je ne parlais qu‘à lui,<br />

je craignais sa colère:<br />

Il m‘aimait tant!<br />

Mais un soir il me dit:<br />

„Dans la sombre vallée<br />

Viendrez-vous avec moi“<br />

Je le promis... pourtant,<br />

En vain il m‘attendit;<br />

je n‘y suis pas allée...<br />

Il m‘aimait tant!<br />

Alors il a quitté<br />

ma joyeuse demeure.<br />

Malheureux!<br />

il a dû me maudire en partant;<br />

Je ne le verrai plus!<br />

je suis triste, je pleure:<br />

Il m‘aimait tant!<br />

Nein, ich liebte ihn nicht!<br />

Bei <strong>sei</strong>nes Werbens Drange<br />

Erglühten wohl die Wangen mir,<br />

doch war das Herz mir schwer<br />

Ich floh vor <strong>sei</strong>nem Blick,<br />

mir ward so ängstlich bange<br />

Er liebte mich so sehr<br />

Ich schmückte mich für ihn,<br />

ihm wollt ich gern gefallen;<br />

mit Blumen schmückte ich mir<br />

die Locken, die Brust.<br />

Ich sprach allein mit ihm,<br />

<strong>und</strong> bebte trotz dem Allen.<br />

Er liebte mich so sehr!<br />

Doch einst sprach er zu mir:<br />

„In den traulichen Garten<br />

Wirst du doch mit mir gehn“<br />

Ich sagte zu <strong>und</strong> brach mein Wort;<br />

Er ging umsonst dahin,<br />

ich ließ den Armen warten.<br />

Er liebte mich so sehr!<br />

Drauf hat er dieses Haus,<br />

meine Nähe gemieden;<br />

Wehe mir! ach, er hat mich<br />

verwünscht, als er ging!<br />

Ich werd ihn nie mehr sehn!<br />

ich bin traurig <strong>und</strong> weine:<br />

Er liebte mich so sehr!<br />

No, I didn’t adore him!<br />

Due to his urging suiting<br />

My cheeks glowed,<br />

still my heart <strong>was</strong> heavy<br />

I escaped his gaze,<br />

timidly trembling.<br />

He did love me so much.<br />

Adorning myself for him,<br />

I wished to appeal to him,<br />

Adorning my curls,<br />

my chest with flowers,

Janina Baechle <strong>und</strong> Charles Spencer<br />

Innerhalb von wenigen Jahren wurde Janina Baechle zu einer der großen Mezzosopranistinnen unserer<br />

Zeit. In Hamburg geboren, studierte sie dort Musikwissenschaft <strong>und</strong> Geschichte. Parallel dazu<br />

nahm sie bei Gisela Litz Gesangunterricht. Später vervollständigte sie ihre Ausbildung bei Brigitte<br />

Fassbaender. Ihren ersten Auftritt hatte sie 1997. Seit 20<strong>04</strong> ist sie Mitglied der Wiener Staatsoper <strong>und</strong><br />

wurde dort zur unentbehrlichen Ortrud, Brangäne oder Quickly. Auf anderen Bühnen hat sie ihrem<br />

Repertoire die Rollen der Amme aus Frau ohne Schatten oder der Amneris aus Aida hinzugefügt,<br />

wobei letztere ihre meistgesungene Rolle ist. Janina Baechle fühlte sich jedoch schon immer zum<br />

Konzert hingezogen. In den letzten Jahren haben ihr die Wiener Philharmoniker die Zweite Symphonie<br />

von Gustav Mahler (unter der Leitung von Seiji Ozawa) <strong>und</strong> das <strong>Lied</strong> von der Erde (unter der Leitung<br />

von Kent Nagano) anvertraut. Viele hörten mit Erstaunen, dass sich diese auf die großen Wagner-Rollen<br />

zugeschnittene Stimme auch für das zarteste pianissimo eignet. Tiana Lemnitz war auch für ihr<br />

piano bekannt – <strong>und</strong> Berlin nannte sie Piana –, sie war jedoch eine Elsa, keine Ortrud. Seit dem<br />

Abschluss ihres Musikstudiums reist Janina Baechle von Konzert zu Konzert <strong>und</strong> trägt dabei das<br />

erstaunlichste Repertoire vor, <strong>sei</strong> es auf Deutsch, Englisch, Französisch, Italienisch oder Russisch.<br />

Selbstverständlich fühlt sie sich wohl bei Brahms, Wolf <strong>und</strong> dem von ihr besonders geschätzten<br />

Mahler. Derzeit spürt sie jedoch eine tiefe Verwandtschaft mit dem französischen Repertoire <strong>und</strong> der<br />

französischen Sprache, die sie besser spricht als die meisten Franzosen. Ein wichtiger Moment war<br />

ihre Begegnung mit Charles Spencer, dem bevorzugten Begleiter von Christa Ludwig, von der Janina<br />

Baechle die meisten Rollen an der Staatsoper übernommen hat. Der in England geborene Charles<br />

Spencer studierte in London <strong>und</strong> Wien. Er begleitete Christa Ludwig zwölf Jahre lang, bis zu ihrer<br />

Abschiedstournee 1993. Er arbeitete auch mit June Anderson, G<strong>und</strong>ula Janowitz, Marjana Lipovsek,<br />

Jessye Norman <strong>und</strong> Thomas Quasthoff zusammen.

There <strong>was</strong> a King of Thule,<br />

faithful to the grave,<br />

to whom his dying beloved<br />

gave a golden goblet.<br />

Nothing <strong>was</strong> more valuable to him:<br />

he drained it in every feast;<br />

and his eyes would overflow<br />

whenever he drank from it.<br />

And when he neared death,<br />

he counted the cities of his realm<br />

and left everything gladly<br />

to his heir –<br />

except for the goblet.<br />

He sat at his kingly feast,<br />

his knights about him,<br />

in the lofty hall of ancestors,<br />

there in the castle by the sea.<br />

There, the old wine-lover stood,<br />

took a last draught of life‘s fire,<br />

and hurled the sacred goblet<br />

down into the waters.<br />

He watched it plunge, fill up,<br />

and sink deep into the sea.<br />

His eyes then sank closed<br />

and he drank not one drop more.<br />

Autre fois un Roi de Thulé<br />

Qui jusqu‘au tombeau fut fidèle<br />

Reçut à la mort de sa belle<br />

Une coupe d‘or viselé;<br />

Comme elle ne le quittait guères<br />

Dans les festins les plus joyeux<br />

Toujours une larme légère<br />

À sa vue humectait ses yeux.<br />

Ce prince à la fin de sa vie<br />

Lègue ses villes et son or,<br />

Excepté la coupe chérie<br />

Qu‘à la main il conserve encor;<br />

Il fait à sa table royale<br />

Asseoir ses Barons et ses Pairs,<br />

Au milieu d‘une antique Salle<br />

D‘un Château que baignaient l<br />

es mers.<br />

Le buveur se lève et s‘avance<br />

Auprès d‘un vieux balcon doré,<br />

Il boit et soudain sa main lance<br />

Dans les flots le Vase sacré;<br />

Il tombe tourne l‘eau bouillonne<br />

Puis se calme bientôt après,<br />

Le vieillard pâlit et frissonne,<br />

Il ne boira plus désormais.<br />

05 Der du von dem<br />

Himmel bist<br />

(Goethe)<br />

Der du von dem Himmel bist,<br />

Alles Leid <strong>und</strong> Schmerzen stillest,<br />

Den, der doppelt elend ist,<br />

Doppelt mit Erquickung füllest,<br />

Ach! ich bin des Treibens müde!<br />

Was soll all der Schmerz <strong>und</strong> Lust<br />

Süßer Friede,<br />

Komm, ach komm in meine Brust!<br />

Thou who comest from on high,<br />

Who all woes and sorrows stillest,<br />

Who, for twofold misery,<br />

Hearts with twofold balsam fillest,<br />

Would this constant strife<br />

would cease!<br />

What are pain and rapture now<br />

Blissful Peace,<br />

To my bosom hasten thou!<br />

Toi qui es du ciel,<br />

Tu calmes peines et souffrances,<br />

Celui qui est deux fois plus<br />

misérable,<br />

Tu le réconfortes doublement,<br />

Ah, je suis fatigué de courir!<br />

Pour quoi tous ces tourments<br />

et plaisirs<br />

Douce paix,<br />

Viens, ah viens en mon coeur!<br />

06 Über allen Gipfeln<br />

ist Ruh<br />

(Goethe)<br />

Über allen Gipfeln<br />

ist Ruh,

<strong>01</strong> Was <strong>Liebe</strong> <strong>sei</strong><br />

(Charlotte von Hagn)<br />

Dichter! <strong>was</strong> <strong>Liebe</strong> <strong>sei</strong>,<br />

mir nicht verhehle!<br />

<strong>Liebe</strong> ist das Atemholen der Seele.<br />

Dichter! <strong>was</strong> ein Kuss <strong>sei</strong>,<br />

du mir verkünde!<br />

Je kürzer er ist,<br />

um so größer die Sünde!<br />

Poet, what love is,<br />

don’t conceal from me:<br />

Love is the breathtaking<br />

of the soul.<br />

Poet, what a kiss is,<br />

proclaim it to me:<br />

The shorter a kiss,<br />

the greater our sin.<br />

<strong>02</strong> Mignons <strong>Lied</strong><br />

(Goethe)<br />

Kennst du das Land,<br />

wo die Zitronen blühn,<br />

Im dunkeln Laub<br />

die Gold-Orangen glühn,<br />

Ein sanfter Wind vom blauen<br />

Himmel weht,<br />

Die Myrthe still <strong>und</strong> hoch<br />

der Lorbeer steht<br />

Kennst du es wohl<br />

Dahin! dahin<br />

Möcht ich mit dir,<br />

o mein Geliebter, ziehn.<br />

Kennst du das Haus<br />

Auf Säulen ruht <strong>sei</strong>n Dach.<br />

Es glänzt der Saal,<br />

es schimmert das Gemach,<br />

Und Marmorbilder stehn<br />

<strong>und</strong> sehn mich an:<br />

Was hat man dir, du armes Kind,<br />

getan<br />

Kennst du es wohl<br />

Dahin! dahin<br />

Möcht ich mit dir,<br />

o mein Beschützer, ziehn.<br />

Kennst du den Berg<br />

<strong>und</strong> <strong>sei</strong>nen Wolkensteg<br />

Das Maultier sucht im Nebel<br />

<strong>sei</strong>nen Weg;<br />

In Höhlen wohnt der Drachen<br />

alte Brut;<br />

Es stürzt der Fels <strong>und</strong> über ihn<br />

die Flut!<br />

Kennst du ihn wohl<br />

Dahin! dahin<br />

Geht unser Weg! O Vater,<br />

laß uns ziehn!<br />

Knowest thou<br />

where the lemon blossom grows,<br />

In foliage dark<br />

the orange golden glows,<br />

A gentle breeze blows<br />

from the azure sky,<br />

Still stands the myrtle,<br />

and the laurel, high<br />

Dost know it well<br />

‘Tis there! ‘Tis there<br />

Would I with thee,<br />

oh my beloved, fare.<br />

Knowest the house,<br />

its roof on columns fine<br />

Its hall glows brightly<br />

and its chambers shine,<br />

And marble figures stand<br />

and gaze at me:<br />

What have they done,<br />

oh wretched child, to thee<br />

Dost know it well<br />

‘Tis there! ‘Tis there<br />

Would I with thee,<br />

oh my protector, fare.<br />

Knowest the mountain<br />

with the misty shrouds<br />

The mule is seeking passage<br />

through the clouds;<br />

In caverns dwells the dragons‘<br />

ancient brood;<br />

The cliff rocks plunge<br />

<strong>und</strong>er the rushing flood!<br />

Dost know it well<br />

‘Tis there! ‘Tis there<br />

Leads our path!<br />

Oh father, let us fare.

MAR-1807 2 LISZT: THE COMPLETE SONGS, VOL. 2 JANINA BAECHLE / CHARLES SPENCER<br />

MAR-1807 2 LISZT: THE COMPLETE SONGS, VOL. 2 JANINA BAECHLE / CHARLES SPENCER<br />

LISZT: THE COMPLETE SONGS, VOL. 2 JANINA BAECHLE / CHARLES SPENCER<br />

MAR-1807 2<br />

LISZT<br />

LIED EDITION<br />

VOL. 2<br />

JANINA BAECHLE MEZZO-SOPRANO<br />

CHARLES SPENCER PIANO<br />

FRANZ LISZT (1811-1886)<br />

<strong>01</strong> Was <strong>Liebe</strong> <strong>sei</strong> (1)*<br />

<strong>02</strong> Mignons <strong>Lied</strong><br />

<strong>03</strong> <strong>Freudvoll</strong> <strong>und</strong> <strong>leidvoll</strong><br />

<strong>04</strong> Es war ein König in Thule<br />

05 Der du von dem Himmel bist<br />

06 Über allen Gipfeln ist Ruh<br />

07 Die Loreley<br />

08 Was <strong>Liebe</strong> <strong>sei</strong> (2)*<br />

09 Il m’amait tant<br />

10 La tombe et la rose<br />

11 Oh pourquoi donc*<br />

12 Was <strong>Liebe</strong> <strong>sei</strong> (3)*<br />

13 Die Fischerstochter*<br />

14 Verlassen*<br />

15 Einst wollt’ ich einen Kranz*<br />

16 Gebet<br />

17 In <strong>Liebe</strong>slust<br />

18 Ich scheide<br />

19 Lasst mich ruhen<br />

20 Des Tages laute Stimmen<br />

schweigen<br />

*First recording / Erstaufnahme<br />

A co-production with ORF<br />

© & P 2009 MARSYAS<br />

Marsyas is a division of ENJA Records.<br />

info@marsyas.biz www.marsyas.biz<br />

Made in Germany. DDD LC 14158<br />

#63757-BIAHCc<br />

MAR-1807 2 DEA 590940700<br />

This multichannel/stereo hybrid<br />

SACD can be played on any<br />

standard compact disc player.