The Art of Legal Convergence By Alexander W ... - Seven Wentworth

The Art of Legal Convergence By Alexander W ... - Seven Wentworth

The Art of Legal Convergence By Alexander W ... - Seven Wentworth

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

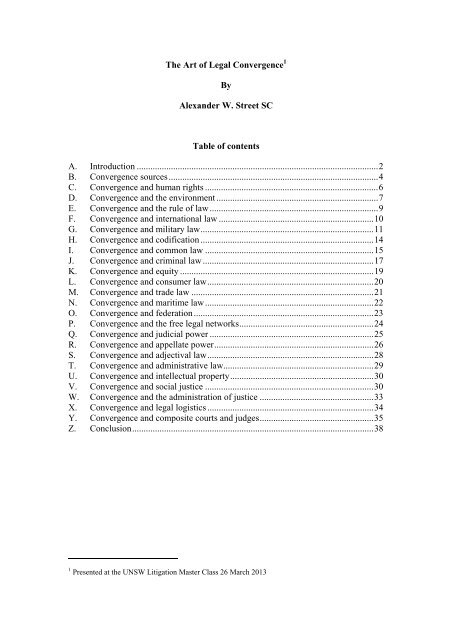

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Legal</strong> <strong>Convergence</strong> 1<strong>By</strong><strong>Alexander</strong> W. Street SCTable <strong>of</strong> contentsA. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 2B. <strong>Convergence</strong> sources ............................................................................................ 4C. <strong>Convergence</strong> and human rights ............................................................................ 6D. <strong>Convergence</strong> and the environment ....................................................................... 7E. <strong>Convergence</strong> and the rule <strong>of</strong> law .......................................................................... 9F. <strong>Convergence</strong> and international law .................................................................... 10G. <strong>Convergence</strong> and military law ............................................................................ 11H. <strong>Convergence</strong> and codification ............................................................................ 14I. <strong>Convergence</strong> and common law .......................................................................... 15J. <strong>Convergence</strong> and criminal law ........................................................................... 17K. <strong>Convergence</strong> and equity ..................................................................................... 19L. <strong>Convergence</strong> and consumer law ......................................................................... 20M. <strong>Convergence</strong> and trade law ................................................................................ 21N. <strong>Convergence</strong> and maritime law .......................................................................... 22O. <strong>Convergence</strong> and federation ............................................................................... 23P. <strong>Convergence</strong> and the free legal networks ........................................................... 24Q. <strong>Convergence</strong> and judicial power ........................................................................ 25R. <strong>Convergence</strong> and appellate power ...................................................................... 26S. <strong>Convergence</strong> and adjectival law ......................................................................... 28T. <strong>Convergence</strong> and administrative law .................................................................. 29U. <strong>Convergence</strong> and intellectual property ............................................................... 30V. <strong>Convergence</strong> and social justice .......................................................................... 30W. <strong>Convergence</strong> and the administration <strong>of</strong> justice .................................................. 33X. <strong>Convergence</strong> and legal logistics ......................................................................... 34Y. <strong>Convergence</strong> and composite courts and judges .................................................. 35Z. Conclusion .......................................................................................................... 381 Presented at the UNSW Litigation Master Class 26 March 2013

2A. Introduction1. <strong>The</strong> calls we hear for unification <strong>of</strong> procedural laws and harmonisation <strong>of</strong>substantive law all derive from an overarching doctrine <strong>of</strong> legal convergence.This doctrine is also at work in the constant confluence <strong>of</strong> disparate legal-righttheories, marshalling <strong>of</strong> organising legal principles, overlapping legal criteriaand alignment <strong>of</strong> legal labels examined under the rational light <strong>of</strong> the judicial orjuristic glare.2. Identification <strong>of</strong> legal convergence requires the false complexity <strong>of</strong> legal jargonto be stripped away by the sunlight <strong>of</strong> reason, clear thinking, order, coherenceand simple language. <strong>The</strong> principle meaning <strong>of</strong> legal convergence that isaddressed in this paper is the merger <strong>of</strong> legal doctrines but there are other legalconcepts <strong>of</strong> a procedural and administrative kind relevant to the administration<strong>of</strong> justice that are also undergoing similar forces <strong>of</strong> convergence. <strong>The</strong> primaryforce in merger <strong>of</strong> the law arises from application and development <strong>of</strong> legaldoctrine by the courts.3. Judicial resolution uses the glare <strong>of</strong> logic to distil and reconcile the conflictingassertions, the contestable premises, the cogency <strong>of</strong> argument, the sufficiency <strong>of</strong>refutations and the more compelling conclusion arising from the application <strong>of</strong>the relevant legal standards. That judicial glare reveals a statement <strong>of</strong> reasonsfor judgment that makes clear the law being applied in the coercive resolution <strong>of</strong>the dispute by judicial power. Prior to the judgment there was a fair process foridentifying the legal principles in issue. Often that process requires a search forthe principles governing interpretation <strong>of</strong> statutory provisions and identification<strong>of</strong> the relevant statutory criteria to be applied in determining the issues <strong>of</strong> factraised by application <strong>of</strong> a statute or other delegated legislation. Constitutionalinterpretation involves scope and division <strong>of</strong> Constitutional powers, obligations,rights, protections, limitations duties and reconciling implications with text,structure, history, principle and precedent are all derived from the sametechniques <strong>of</strong> judicial glare.4. <strong>The</strong> same judicial glare and fair process are applied in determining theunwritten legal rights or remedies by identification and application <strong>of</strong> the legalprinciples that are in issue and determining the derivative factual issues.

3Judicial glare by reasons for judgment must meet expectations <strong>of</strong> predictabilityand accountability as well as being reviewable for error. <strong>The</strong>se judicial reasonsmust maintain certainty <strong>of</strong> principle, transparency <strong>of</strong> process and comply withjudicial methodology for determination <strong>of</strong> the findings <strong>of</strong> fact. Those findings <strong>of</strong>fact on the derivative factual issues arise from the legal issues in contest and aresourced in the evidence adduced or legitimate evidentiary presumptions. <strong>The</strong>sufficiency and quality <strong>of</strong> the evidence from which the derivative factual issuesare decided require judicial reasons that disclose an accountable reasoningprocess. Those reasons are a convergence <strong>of</strong> the former dispute into a new state<strong>of</strong> legal affairs or legal charter, subject only to correction by appealable error.5. Whilst we might point to current aspects <strong>of</strong> the legal system as being derivedfrom identifiable sources and as a refinement <strong>of</strong> earlier theory or approach,generally inadequate attention has been given to the sources, forces and effect <strong>of</strong>the convergence <strong>of</strong> law.6. Attention to these matters may provide an insight and reference point fromwhich deficiencies in earlier theory can be demonstrated or a more enlightenedlegal frame <strong>of</strong> reference adopted that distils and simplifies or more crisplydifferentiates. <strong>The</strong> confluence <strong>of</strong> correctly identified legislative purpose justlike the known genesis <strong>of</strong> the commercial transaction merges with the text <strong>of</strong> theinstrument or document to permit extraction <strong>of</strong> the legal meaning. Thisconfluence <strong>of</strong> law, by revelation <strong>of</strong> harmonizing principles and unified doctrine,is a constructive mechanism to reconcile inconsistency, to simplify legalrequirements, to provide greater clarity <strong>of</strong> the law, to resolve legal conflict andto shape future legal policy.7. All divergent legal doctrine must in theory meet at some level <strong>of</strong> confluxbecause law means compulsion. On closer examination a perceived divergencemay collapse, blend or merge into a single holistic legal concept or a coreprinciple with cascading legal criteria and qualifications. <strong>The</strong> blurring <strong>of</strong> legalprinciple may arise from the myth <strong>of</strong> bright lines or a false assumed dichotomy.It may be that the conflux is a gauge to test or disprove a legal conclusion.<strong>The</strong>re could be at work misplaced legal transference where the desire toadvance legal convergence creates a flawed fusion. <strong>The</strong> limits <strong>of</strong> legalconvergence may be a definable edge <strong>of</strong> principle or just tributaries <strong>of</strong>

4undefinable exception. At one level all reduction <strong>of</strong> legal principle is aconvergence <strong>of</strong> law.8. What artistic appreciation do we as lawyers have <strong>of</strong> the confluction <strong>of</strong> thelabyrinth <strong>of</strong> streams and currents in the workings <strong>of</strong> the law? <strong>The</strong> search for ariparian time-line <strong>of</strong> legal doctrine growth, whether up or down stream in theflow <strong>of</strong> the law, whether a stagnant and discordant legal pool or a tempestuoussea <strong>of</strong> legal conflict may help us understand the spring <strong>of</strong> legal reason, identifythe real legal estuary, properly separate and calm distinct legal seas, and therebyreveal opportunities for greater unification <strong>of</strong> the law or advancement <strong>of</strong> legalpolicy and law reform.9. <strong>The</strong> excited jurist, in academic writing as to particular legal theory, seeks toexamine the adequacy <strong>of</strong> judicial glare in identification <strong>of</strong> the real legalprinciple and assists in accountability <strong>of</strong> judicial process. <strong>The</strong> keen legal scholarmay then explore other potential doctrinal origins, such as Roman law, in thedevelopment <strong>of</strong> the legal theory and then advance recognition <strong>of</strong> what may inreality be the convergence <strong>of</strong> law.10. <strong>The</strong> art <strong>of</strong> this legal convergence and expanding our appreciation <strong>of</strong> its past,current and future influence from an Australian law viewpoint, are the focus <strong>of</strong>discussion in this paper. This canvas etching <strong>of</strong> legal convergence and the briefartwork topics are intended to enthuse interest in legal convergence and topromote the brushwork <strong>of</strong> others so as to reveal the harmony, refinement andreduction <strong>of</strong> legal principle.B. <strong>Convergence</strong> sources11. Scholars and academics are at the forefront <strong>of</strong> the convergence vanguard bytheir continuous analysis, review, critique, comparison, challenge and creativelegal vision. <strong>The</strong> propagation <strong>of</strong> differing legal views leads to inevitablerefinement and restatement <strong>of</strong> the law based on sounder and more finiteprinciple, whilst discarding the less certain, the less rational and the lesscoherent.12. <strong>The</strong> kaleidoscope image <strong>of</strong> our legal system is confined by the lens <strong>of</strong> theindividual. Whilst we may all perceive different patterns and shapes <strong>of</strong> the legal

5puzzle on each glance, the combined collage <strong>of</strong> legal principle has structuralcohesion and is logically unified.13. This universe <strong>of</strong> legal theory and the underlying objective or subjective legalcomponents must be capable <strong>of</strong> identifiable application. A precise andexhaustive definition <strong>of</strong> legal doctrine is unattainable. However all legaldoctrine is formulated by reference to general or flexible standards anddiscretion. <strong>The</strong> real beauty in the constructs <strong>of</strong> the law is the malleability <strong>of</strong>principle to a formulation <strong>of</strong> legal doctrine that serves and advances mankind inthe resolution <strong>of</strong> justiciable disputes.14. <strong>The</strong> principles found in judicial determinations and extra-judicial speeches orwritings contribute to the rich tapestry <strong>of</strong> legal theory to which the magnifyingglass <strong>of</strong> convergence may be applied and may reveal a bigger unifying picture.15. This convergence <strong>of</strong> the law is a gravitational force that is not simply sourced inthe inspiration and sagacity <strong>of</strong> jurists any more than it is beholden to theexternal formulation <strong>of</strong> international law. <strong>The</strong> gravitational influence <strong>of</strong>convergence <strong>of</strong> the law is one <strong>of</strong> logic. As laws are in principle common sensebased it follows that legal common sense logic is readily capable <strong>of</strong> application.Common sense is felicitous <strong>of</strong> meaning and infectious by appealing to theintellect. Moreover just as law is compelling in its force, so too is commonsense logic. So the logic behind legal doctrines when properly understoodfacilitates identification <strong>of</strong> overlapping themes and recognition <strong>of</strong> capacity forfurther refinement and reduction. Accordingly logic is a dominant source thatdrives formulation <strong>of</strong> law and legal convergence.16. <strong>The</strong> paramount force that lies behind legal convergence is the global selfinterest<strong>of</strong> survival and interdependent economic costs and benefits. Thoseeconomic costs and benefits arise across the vast veldt <strong>of</strong> human interaction anddemocratic dependence upon the rule <strong>of</strong> law. <strong>The</strong>se economic considerationsare the driving force behind unification <strong>of</strong> the laws <strong>of</strong> armed conflict, theprevention <strong>of</strong> wars, the maintenance <strong>of</strong> internal stability and the protection <strong>of</strong>human rights.17. <strong>The</strong>re are similar economic benefits that flow from harmonising laws t<strong>of</strong>acilitate trade, productivity and sustainable industry as well as the creation <strong>of</strong>

6agreements to prevent parochial protections and tariffs. Environmental laws tomaintain a sustainable environment have a significant economic impact thatdrives global unification <strong>of</strong> green regulatory systems.18. Indeed the preservation <strong>of</strong> political power is closely aligned with each <strong>of</strong> theabove economic and humanitarian considerations. It is in turn political powerthat utilises legislative lawmaking power. In this sense political survival is alsoa significant force in the advancement <strong>of</strong> legal convergence.C. <strong>Convergence</strong> and human rights19. Whilst development, understanding, implementation, adherence andenforcement <strong>of</strong> human rights will ever be an aspiration <strong>of</strong> those who areoppressed, those who are treated unequally, those who are the subject <strong>of</strong>discrimination, those who are vilified, those who are disenfranchised, those whoare socially invisible and those who try to advance humanity, these are endlessSisyphean struggles. Shifting fears, ignorance, bias and prejudice is a function<strong>of</strong> intellect, needs, powers and education. Advancement <strong>of</strong> human rights willalways require renewed education as to the peaceful right <strong>of</strong> every person torespect and dignity. This requires a safe, secure and balanced opportunity tolearn, comprehend, exercise and enjoy the smorgasbord <strong>of</strong> peaceful legalfreedoms and rights converged in the simple label <strong>of</strong> human rights.20. <strong>The</strong> calls for a bill <strong>of</strong> rights, properly entrenched so as to bind legislative andexecutive powers, is a cause at the heart <strong>of</strong> the UN Universal Declaration <strong>of</strong>Human Rights, 1948. This unification <strong>of</strong> human rights law is a common cause<strong>of</strong> all mankind and the convergence <strong>of</strong> human rights law has been muchadvanced in the last 60 years. Discord as to what is a human right, whetherabsolute, what qualifications and what remedies will still take centuries toresolve. However the content <strong>of</strong> all human rights is the advancement <strong>of</strong>humanity and that means that these rights are all <strong>of</strong> a peaceful purpose andpeaceful limitation.21. <strong>The</strong> constant refinement <strong>of</strong> monotheistic belief systems and other religiousorders reflects humanities search for meaning, order and purpose. <strong>The</strong> merger <strong>of</strong>some <strong>of</strong> those belief systems and fracturing <strong>of</strong> others is a cycle linked toadvancement <strong>of</strong> mankind, education, poverty, wealth, resources and survival.

7Whilst all belief systems are capable <strong>of</strong> harmonious co-existence that is rarelyconceived as the true purpose and so a struggle for dominance, which is in factunachievable, continues.22. <strong>Convergence</strong> <strong>of</strong> religious belief systems is an influence <strong>of</strong> convergent legalsystems. Religious law is itself a system that is on the verge <strong>of</strong> being swallowedup by the secular rule <strong>of</strong> law. Given the unsolvable struggle, all religious beliefsand religious law are doomed to face the advancement <strong>of</strong> humanity.Accordingly there is sound reason to advance convergence <strong>of</strong> legal systemsunder a secular and supreme doctrine <strong>of</strong> the rule <strong>of</strong> law.23. A danger that human rights law convergence faces is manipulation andextension to protect rights that are not human rights. <strong>The</strong> extension is likely tomask the reality <strong>of</strong> a watering down <strong>of</strong> existing peaceful freedoms. That said theconvergence <strong>of</strong> human right concepts into domestic law continues to have veryconstructive impacts including the development <strong>of</strong> the legislative clarityrequired as a matter <strong>of</strong> statutory interpretation for a valid law that constrains afundamental human right.24. <strong>The</strong> domestic implementation <strong>of</strong> this convergence for enforcement <strong>of</strong> humanrights sometimes goes too far such as the creation <strong>of</strong> a criminal <strong>of</strong>fence forserious ridicule. This is close to creating a criminal <strong>of</strong>fence for want <strong>of</strong> respectto another person or failure to treat with appropriate dignity. Whilst civilremedies for breach <strong>of</strong> human rights are to be applauded, there is a need forconstraint in the creation <strong>of</strong> human right <strong>of</strong>fences that effectively constrainpeaceful freedom <strong>of</strong> speech.D. <strong>Convergence</strong> and the environment25. <strong>The</strong> pandemic <strong>of</strong> industrialisation has brought a plague <strong>of</strong> industrial pollution.Balancing the interests <strong>of</strong> human advancement against human degradation anddestruction <strong>of</strong> the environment is a grim self-interested legal nightmare.Sustainable utilization <strong>of</strong> resources for a species that has over populated theplanet is impossible to achieve but unquestionably an object to be strived for, ifnot for blissful enjoyment <strong>of</strong> the unborn generations <strong>of</strong> our epoch, then at leastfor the promotion <strong>of</strong> peace and tranquillity between nations.

826. <strong>The</strong> biggest issue that confronts cohesion <strong>of</strong> environmental law is thecataclysmic consequences <strong>of</strong> climate change. <strong>The</strong> content <strong>of</strong> climate changemeans not just the consequential collapse <strong>of</strong> eco-systems, lost habitat, speciesextinction, diminished quality <strong>of</strong> air, water shortage, tableland salinity andincreased sea acidity from rising temperatures and sea levels but includesincreasing natural disasters from drought, fire, flooding, sulphuric rain, landslip,tsunamis, volcanic degradation and tectonic plate movements.27. <strong>The</strong>se impacts alone have a massive financial impact, from reduced primaryproduction, impaired trade routes, lost or damaged housing, property andinfrastructure, increased disease and plagues across carbon life forms, as well asthe consequential increase <strong>of</strong> costs for consumers, humanitarian bodies, healthservices and the public purse <strong>of</strong> Government. <strong>The</strong> disruption to primaryindustry, business activities, tourism, hospitals, medical and emergency servicesfrom climate change includes market impact on all related retail and wholesalebusiness entities including insurers, reinsurers and climate-sensitive businessinvestors and non-government funders. <strong>The</strong>se are economic incentives toachieve unified law to reduce climate harmful emissions and to developsustainable clean energy and environmentally friendly human activities.28. <strong>The</strong> international agreements aimed at reducing carbon emissions, advancingclean energy, maintaining habitats and diversification <strong>of</strong> species are in directconflict with the advancement <strong>of</strong> the industrial and technological age. <strong>The</strong>protection <strong>of</strong> the environment is not easily reconciled with free trade agreementsand growth <strong>of</strong> labour workforce wages, wealth and opportunities. <strong>The</strong> complexraft <strong>of</strong> intentional incentives and disincentives to implement internationalenvironmental agreements are economic tools that inevitably impact on theadvancement <strong>of</strong> society.29. Whilst it is essential to have a sustainable environment for the people <strong>of</strong>tomorrow, the burden <strong>of</strong> climate related law reform is a political noose upon thedrivers <strong>of</strong> economic expansion and growth. As survival <strong>of</strong> humanity is moreimportant than fiscal policy there will be a continuing convergence <strong>of</strong>international law designed to reduce the causes and impact <strong>of</strong> climate changeand to preserve the environment. Domestic implementation by all countries <strong>of</strong>

9international climate change agreements and clean energy reforms is the mostimportant legal convergence for mankind.E. <strong>Convergence</strong> and the rule <strong>of</strong> law30. A rule <strong>of</strong> law democracy must advance social order.<strong>The</strong> “have nots” will neverremain content and contained so “the haves” need more than social order topreserve standards <strong>of</strong> living. <strong>The</strong> compulsion inherent in the rule <strong>of</strong> lawincluding the coercive effect <strong>of</strong> the exercise <strong>of</strong> judicial power is designed toadvance that social order. “<strong>The</strong> haves” need a social conscience and from thatmotivational spring a continuous implementation <strong>of</strong> actions to advance socialreform, social equality, social education, social welfare, social employment,social health, social recreation and social opportunity.31. Failure to implement these social conscience actions drives the struggle <strong>of</strong>humanity for recognition, restitution, retribution and survival. Whilst alltyrannies are doomed there is no easy fix by harnessing masses in a democraticgovernance unless the elected government addresses matters <strong>of</strong> socialconscience. A monarchy, a plutocracy, meritocracy or stratocracy can never bea panacea for the disenfranchised, the destitute, the disadvantaged and thedestabilised as the rule <strong>of</strong> law is not by the people.32. In any rule by the people the essentials <strong>of</strong> health, food, water, shelter andsecurity are in tension with employment, wealth, capitalism and marketeconomies. Oppression <strong>of</strong> people under religious ideologies, cults and criminalorganisations are flawed by false freedoms, failure <strong>of</strong> fear based power and theunquenchable thirst for intellectual and physical liberty.33. Socialist structures advancing what may appear to be worthy communisticideals <strong>of</strong> community ownership, rule and inter-dependent functioning are als<strong>of</strong>undamentally flawed by the inevitable corruption <strong>of</strong> unaccountable politicalpower, the anarchy <strong>of</strong> destroyed ambition and the apathy <strong>of</strong> lost motivation <strong>of</strong>self-interest. Social co-operation is most effective when our more basicinstincts for advancing self are blended with community advancement, nationalidentity, people-made constitutional governance and sovereignty <strong>of</strong> the people,by the people, for the people under the rule <strong>of</strong> law.

1034. <strong>The</strong> convergence <strong>of</strong> social governance under the rule <strong>of</strong> law is readily visible tothe historian. <strong>The</strong> fall <strong>of</strong> rule by monarchs and the development <strong>of</strong>parliamentary power <strong>of</strong> the people litters the past <strong>of</strong> Europe. Equally thecollapse <strong>of</strong> the USSR bespeaks the problems <strong>of</strong> communistic rule althoughChina in its continuing glory <strong>of</strong> economic growth continues to defy the punditsas to the inevitability <strong>of</strong> western democratisation. But in each strong coherentnation there is a functioning and effective legal system for the administration <strong>of</strong>justice and advancement <strong>of</strong> the rule <strong>of</strong> law by the people.35. <strong>The</strong> greatest drivers <strong>of</strong> convergence <strong>of</strong> the rule <strong>of</strong> law are the growth <strong>of</strong> theglobal economy, advances in almost instant wireless digital communication,increased speed and efficiency <strong>of</strong> transportation and the shrinking <strong>of</strong> parochialprotectionism. But the recent banking system caused depression reveals acapitalistic fault-line through unregulated financial products, deficientprudential standards, ineffective market regulation, manipulated credit agencies,imbalanced auditing and accounting standards, all compounded by inadequatelymonitored automated market transactions, impaired circulation <strong>of</strong> money andour flawed traits <strong>of</strong> greed and fear. Whilst global economic shocks will remainas predictable as seismic shifts the fault-lines are at least diminished byaccountable legal reforms and this in turn re-enforces the cause <strong>of</strong> convergence<strong>of</strong> the rule <strong>of</strong> law.F. <strong>Convergence</strong> and international law36. <strong>The</strong> trade based growth <strong>of</strong> international law has diversified into all spheres <strong>of</strong>human activity. <strong>The</strong> Charter <strong>of</strong> the United Nations dated 26 June 1945 has beenthe source <strong>of</strong> considerable legal convergence. From regulating air space, seas,ships, satellites, human rights, warfare and weapons, banking systems, wages,disease, to property rights there are international treaties, multi-lateral Stateagreements as well as related world organisations and other non-governmentbodies. Advancing any <strong>of</strong> these regulatory causes requires uniformity and legalimplementation. So international law is at the apex <strong>of</strong> drivers for legalconvergence.37. Within these areas <strong>of</strong> public law are inevitable tensions and conflicts in trying toachieve a balance <strong>of</strong> the competing stakeholder interests. <strong>The</strong> public law

11product from international agreements are inevitably a compromise so as toachieve a consensus that leaves exceptions, carve outs or ambiguity thatdiminish the underlying objectives <strong>of</strong> unification.38. <strong>The</strong> desirability for common interpretation <strong>of</strong> international instruments has leadto its own treaty being the Vienna Convention but inevitably separate legalsystems maintain their own sovereignty in the domestic application <strong>of</strong> treatybased law. Concepts <strong>of</strong> international comity have strengthened the likelihood <strong>of</strong>certainty by uniformity <strong>of</strong> approach and following <strong>of</strong> compelling higher courtprecedents but exceptions and dissonant decisions are the reality <strong>of</strong>compromised treaties. <strong>The</strong>re are now international UN based tribunals andcourts that have massively advanced the convergence <strong>of</strong> the law <strong>of</strong> the seas, warcrimes and crimes against humanity.39. International law will inevitably continue to be the greatest driver <strong>of</strong> legalconvergence by dissemination <strong>of</strong> collective standards and facilitating theconsequential implementation <strong>of</strong> uniform laws. <strong>The</strong> increasing interaction andcoherence <strong>of</strong> legal systems is also enhanced by the incredible improvement incommunication and transportation.40. From academic interaction, international legal conferences to the interactionbetween judicial <strong>of</strong>ficers from around the globe, there is an increasingawareness <strong>of</strong> the existence, importance and role <strong>of</strong> complimentary andharmonious legal systems in the common cause <strong>of</strong> advancing and administeringinternational law. This facilitates the advancement <strong>of</strong> legal convergence.G. <strong>Convergence</strong> and military law41. Many common law countries are starting to address the disparity <strong>of</strong> legal rightsand tribunals that exercise powers over defence members and prisoners that failto replicate the ordinary criminal law. Most <strong>of</strong> these tribunals were extensions<strong>of</strong> military command and anything but independent bodies that could withstandmodern expectations <strong>of</strong> judicial independence and the separation <strong>of</strong> courts fromthe state, church, legislature or executive.42. <strong>The</strong>se modern expectations are closely tied to the maintenance <strong>of</strong> publicconfidence in and respect for the exercise <strong>of</strong> judicial power and maintenance <strong>of</strong>the rule <strong>of</strong> law. <strong>The</strong> exercise and maintenance <strong>of</strong> which are essential for

12preservation <strong>of</strong> the Constitutional institutions that are the foundations for avibrant, diverse and harmonious democracy.43. <strong>The</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> the appearance <strong>of</strong> judicial independence and the separation<strong>of</strong> courts from any deflective influence sits uncomfortably with a want <strong>of</strong>convergence <strong>of</strong> constitutional law in respect <strong>of</strong> military judicial power.Expressions <strong>of</strong> dismay at unfair treatment <strong>of</strong> defence members or prisoners <strong>of</strong>war are all reflections <strong>of</strong> the public expectation <strong>of</strong> the proper exercise <strong>of</strong>criminal law by independent and impartial courts.44. <strong>The</strong> desires <strong>of</strong> military command influenced by centuries <strong>of</strong> separate disciplinesystems from mainstream criminal law create a significant impediment in theconvergence <strong>of</strong> criminal law and military law. But the confluence is inevitableand the perceived conflict with the need to maintain discipline is utterlyartificial and in fact a military command myth.45. Whilst it is fair and necessary for military command to have powers to dismiss,reduce in rank, forfeit seniority, fine or reprimand, these are the proper metesand bounds <strong>of</strong> disciplinary power and all other powers <strong>of</strong> imprisonment or socalled detention are the domain <strong>of</strong> criminal law and the independent judicialinstitutions. Whilst some may argue in favour <strong>of</strong> re-educational orrehabilitation detention by military command power this is out <strong>of</strong> harmony withall other discipline systems.46. To detain any person, is an interference with the fundamental human right <strong>of</strong>liberty. This deprivation <strong>of</strong> liberty should only ever occur by or in pursuit <strong>of</strong>exercise <strong>of</strong> independent judicial power. In pursuit should be confined todeprivation <strong>of</strong> the liberty <strong>of</strong> the person by arrest in the nature <strong>of</strong> temporarycustody to prevent flight for the purpose <strong>of</strong> being brought to court for exercise<strong>of</strong> the judicial power in a timeframe consistent with all reasonable expedition.47. So no person should be detained by any exercise <strong>of</strong> executive power other thanfor the purpose <strong>of</strong> bringing the person before an independent court. That courtcan determine whether loss <strong>of</strong> liberty should be continued and if so whatrestrictions <strong>of</strong> liberty are consistent with legal principle as to the presumption <strong>of</strong>innocence. That court can balance the interests <strong>of</strong> liberty <strong>of</strong> the accused with

13the public interest in the remand, bail, trial and punishment <strong>of</strong> those whotransgress the criminal law.48. All prisons and all sentences <strong>of</strong> imprisonment include objects <strong>of</strong> rehabilitationand there is no justification for military detention outside <strong>of</strong> the criminal law.Considerable international interest relating to the confluence <strong>of</strong> military andcriminal law arises in the treatment, bringing to trial and punishment <strong>of</strong> allegedprisoners <strong>of</strong> war. Sadly parochial and self-interested interpretations <strong>of</strong> theGeneva Conventions have failed to consistently apply those internationalminimum standards for treatment <strong>of</strong> prisoners <strong>of</strong> war by interpretations <strong>of</strong>enemy combatants that are inconsistent with most modern military conflicts.49. <strong>The</strong> rhetoric <strong>of</strong> terrorism has been used to deny proper application <strong>of</strong> theGeneva Conventions to so-called terrorists and the consequential abuse <strong>of</strong>prisoners at various locations have been endemic. <strong>The</strong> sunlight disinfectantintended by application <strong>of</strong> the spirit <strong>of</strong> the Geneva Conventions would haveprevented these horrific abuses <strong>of</strong> human rights by those exercising militarypower over prisoners.50. So the convergent forces <strong>of</strong> criminal and military law are fuelled by publicexpectations. Whilst there will still be scope for criminal <strong>of</strong>fences to deal withmilitary command interests the convergence <strong>of</strong> military law into criminal law isinevitable. Moreover disbanding the antiquated military tribunals from anycontinued exercise <strong>of</strong> military judicial power is an end much to be welcomed.51. No person should face a different criminal law standard <strong>of</strong> trial or a differentsentence for substantially the same crime. No person convicted <strong>of</strong> what is insubstance the same crime should have differing appellate rights. <strong>The</strong>sedifferences are entrenched in military judicial power and it is an unfairness thatis utterly discordant with the rule <strong>of</strong> law.52. <strong>The</strong> convergence <strong>of</strong> military tribunals into mainstream criminal courts is <strong>of</strong>critical importance for the maintenance <strong>of</strong> our democracy. This is not to saythat all military tribunals did not seek to exercise their powers properly but thereis a vast chasm between non-independent tribunals and independent courts.53. Those who contend that wartime and the fog <strong>of</strong> war do not permit <strong>of</strong> theseniceties underestimate the critical importance <strong>of</strong> the rule <strong>of</strong> law. Once we

14abandon the rule <strong>of</strong> law under the guise <strong>of</strong> military necessity we have lost ourdemocracy and only anarchy or despotism will be the likely outcome.Accordingly, convergence <strong>of</strong> military and criminal courts is also an essentialobject for advancement and preservation <strong>of</strong> our democracy.H. <strong>Convergence</strong> and codification54. <strong>The</strong> recent commencement <strong>of</strong> a Commonwealth review as to whether the law <strong>of</strong>contract should be the subject <strong>of</strong> codification is a fascinating example <strong>of</strong> lawreform driven legal convergence. This potential codification <strong>of</strong> contracthighlights the complex issues that can be thrown up in attempts to simplify andunify the law.55. Complete codification <strong>of</strong> the law <strong>of</strong> contract is a worthy objective, howeverreconciling that exercise with the remaining spheres <strong>of</strong> uncodified lawconcerning torts and equity becomes a tangled web. Unless all intersectingareas <strong>of</strong> the law are codified for contracts, torts and equity, the desiredsimplification will not be achieved and the incomplete codification will createan endless feast for lawyers by formulation and pursuit <strong>of</strong> rights in tort or equitythat have not been effectively constrained by the codification <strong>of</strong> contract law.56. An effective example <strong>of</strong> an attempt to constrict other avenues <strong>of</strong> remedy wereaddressed by the reforms to the Trade Practices Act 1974 that introducedproportionate liability and contribution as a result <strong>of</strong> the sterling Review <strong>of</strong> theLaw <strong>of</strong> Negligence by the Hon. Justice Ipp AO QC. <strong>The</strong>re remain discordantgaps and scope for dispute to escape application <strong>of</strong> the proportionalityprovisions and arguments as to coordinate liability outside the scope <strong>of</strong> thestatutory reform.57. This only highlights the difficulty involved in codification which is not designedto encompass all areas <strong>of</strong> unwritten law. Whilst this may be a Herculean task inthe eyes <strong>of</strong> a common lawyer, it was grist for the codex mill <strong>of</strong> the EmperorJustinian. Complete codification is a worthy object. Whilst convergence <strong>of</strong>unwritten law into an exhaustive code may be an admirable end, there remains aneed for transparency <strong>of</strong> the law.58. Codification that becomes overly complex, prolix and unintelligible does notadvance predictability and certainty required by the rule <strong>of</strong> law. Telephone

15books <strong>of</strong> codified laws will not assist the orderly and efficient functioning <strong>of</strong>either the business world or modern society. It is the reduction <strong>of</strong> the telephonebooks <strong>of</strong> legislation into digestible, coherent and simple statutory language thatis the most difficult task. That task is compounded by the inevitable discovery<strong>of</strong> omissions and errors and the shift in political powers or social mores thatgenerally give rise to law reform.59. <strong>The</strong> changeability <strong>of</strong> what is codified is as important as its content. <strong>The</strong>re willinevitably be a continuous breathing in and out <strong>of</strong> the statutory content thatseeks to govern the people <strong>of</strong> the Commonwealth. In this regard, it is greatly tobe commended that the standards employed by the Office <strong>of</strong> ParliamentaryCounsel are available to the cathartic observation <strong>of</strong> all and are <strong>of</strong> an extremelyhigh calibre and content. It is much to be hoped that the pressures forconvergence <strong>of</strong> the unwritten law into a uniform codification will have thebenefit <strong>of</strong> the skill and distillation that flows from the high standards <strong>of</strong> theOffice <strong>of</strong> Parliamentary Counsel or the similar exemplary standards <strong>of</strong> theAustralian Law Reform Commission.I. <strong>Convergence</strong> and common law60. <strong>The</strong> statements <strong>of</strong> the High Court <strong>of</strong> Australia that there is a single common laware a logical reflection <strong>of</strong> the Australian Constitution and also reflect thedoctrine <strong>of</strong> convergence in relation to common law. Whilst there remainfascinating areas to reconcile for the centuries ahead as to the content andintersection <strong>of</strong> Native Title and other Aboriginal cultural rights and customswithin the rubric <strong>of</strong> common law, this unwritten body <strong>of</strong> doctrines recognisedby the old common law courts <strong>of</strong> England appear antiquated. That said therehas already occurred considerable legal convergence in common law doctrinefrom the civil law systems and in particular notions <strong>of</strong> commutative justice.61. Moreover, reconciling the content <strong>of</strong> common law in Australia with thedoctrines <strong>of</strong> equity and concepts <strong>of</strong> fusion <strong>of</strong> law and equity, as well as allegedfusion fallacy all appear unnecessary relics. A more meaningful distinction anddivision for Australian law may be federal law and State law. It is submittedthis would more closely align with s5 <strong>of</strong> the Commonwealth <strong>of</strong> AustraliaConstitution Act and with the language <strong>of</strong> the Constitution, particularly ss109

16and 118. Further this division also leaves scope for a wider operation as to themeaning <strong>of</strong> “a law <strong>of</strong> the Commonwealth” in s80 <strong>of</strong> the Constitution.62. It is tempting to engage in a more detailed analysis <strong>of</strong> common law doctrines,all <strong>of</strong> which are ultimately derived from common sense. Whilst common sensehas become a touchstone for causation in tort law, it may be that the salientfeatures and propinquity <strong>of</strong> relationship that govern the nature and scope <strong>of</strong> aduty <strong>of</strong> care are capable <strong>of</strong> being subsumed within an overarching doctrine <strong>of</strong>common sense.63. <strong>The</strong> problem created by such an overarching doctrine is the loss <strong>of</strong> identifiableand accurate yardsticks. Value-based concepts <strong>of</strong> what is just or what is fairprovide no tangible content. Tangible content is necessary in the law forpredictability, certainty and accountability in the application <strong>of</strong> legal principle.This is the same problem that inhibits notions <strong>of</strong> sweeping generality such asunconscientious conduct or unjust enrichment as black hole doctrines that mightsubsume identifiable causes <strong>of</strong> action, concepts <strong>of</strong> estoppel and equitable rightsand remedies. <strong>The</strong> problem with an overarching black hole doctrine is that itsucks away the content that permits identification <strong>of</strong> the principles to be appliedand reviewability <strong>of</strong> the application <strong>of</strong> those principles.64. This does not mean that there should not be continuing endeavours to refine andnarrow the categories <strong>of</strong> estoppel into a coherent and singular doctrine butrather that there will always remain a need for identifiable legal criteria. <strong>The</strong>change in labels <strong>of</strong> those legal criteria is inevitable just as the changing guard <strong>of</strong>precedent tends to restate, sometimes with refinement, every ten years or so thegist <strong>of</strong> legal reasoning required to sustain or to defeat a right, obligation orremedy.65. <strong>The</strong> sphere <strong>of</strong> tortuous conduct based on the old forms <strong>of</strong> action may in duecourse be subsumed into an action for wrongful conduct where unreasonableconduct occurs that causes foreseeable injury or loss to an identifiable classlikely to suffer loss from unreasonable conduct. Statutory remedies andlimitations are likely to further circumscribe the common law concerning tortsto person and property. For example statutory reform in the area <strong>of</strong> legalpr<strong>of</strong>essional privilege effectively modified the common law sole purpose test to

17a broader dominant purpose test in creation <strong>of</strong> the document for establishing theprivilege. In this sense statutory reform will further drive convergence <strong>of</strong>common law doctrine.66. One <strong>of</strong> the areas <strong>of</strong> the law <strong>of</strong> contract that is under continuing pressure tojustify its continued existence relates to the doctrine <strong>of</strong> consideration. Whilstthere has been some statutory abrogation <strong>of</strong> the common law doctrine <strong>of</strong>contract, the reforms recently made to the Australian Consumer Law are likelyto drive a review <strong>of</strong> the role <strong>of</strong> the principles concerning consideration andwhether there should emerge a new doctrine <strong>of</strong> legal obligation that requires nomore than the objective intention <strong>of</strong> the parties and sufficient certainty.67. <strong>The</strong> public policy underlying enforcement <strong>of</strong> legal obligations or bargains isalso the same chameleon tool that renders unenforceable agreements in restraint<strong>of</strong> trade, founded on illegality, uncertainty, duress, fraud or mistake. Thatchameleon tool <strong>of</strong> public policy underlies the existence <strong>of</strong> all common law legalrights and the qualifications or exceptions. So common law is a fertile field foradvancement <strong>of</strong> legal convergence.J. <strong>Convergence</strong> and criminal law68. One <strong>of</strong> the areas that has created complexity for those the subject <strong>of</strong> regulatoryauthority is the increasing endeavour to use civil penalty provisions to providean effective tool to protect the public and penalise conduct that might otherwisefall short <strong>of</strong> an ability to obtain a criminal conviction. A similar concern arisesin relation to Commissions or Tribunals that make declarations <strong>of</strong> improperconduct with the flavour or overtones <strong>of</strong> criminality such as corrupt conduct.69. This increasing use <strong>of</strong> civil penalty legislation and non-court bodies that canmake declarations <strong>of</strong> corrupt conduct are an attempt to converge criminal lawinto civilian law. Whilst the worthy object <strong>of</strong> regulatory authorities is advancedby attempts to protect the public, it should not be at the expense <strong>of</strong> the ordinaryhuman rights concerning the presumption <strong>of</strong> innocence, right to silence andburden <strong>of</strong> pro<strong>of</strong> upon the prosecution.70. Whether the pendulum swing has gone too far in current civil penaltylegislation, particularly given the growth <strong>of</strong> related administrative tribunals andpowers will be a continuing sphere in which Courts endeavour to regain and

18retain their role as the cornerstone for determination <strong>of</strong> civil and criminalcontroversies.71. Crimes in the digital world are obviously an area for legal convergence. <strong>The</strong>reare, however, too many fields <strong>of</strong> attempted refinement <strong>of</strong> the criminal law toexplore in detail but it remains concerning that fundamental rights <strong>of</strong> an accusedto silence are under constant attack from the forces <strong>of</strong> political martinets to theforces <strong>of</strong> case management. Similar attacks are advanced on the criminal jurytrial by promotion <strong>of</strong> judge alone criminal trials.72. <strong>The</strong> scope and work <strong>of</strong> s80 <strong>of</strong> the Constitution on the State and federal criminallaw will continue to unify and protect fundamental features <strong>of</strong> the criminal jurysystem which serve both the interests <strong>of</strong> an acceptable public verdict and theinterests <strong>of</strong> fair trial for an accused. <strong>The</strong> American due process protections arelikely to be found in substance to exist in the fair process implications <strong>of</strong>Chapter III. <strong>The</strong> implication <strong>of</strong> entitlement <strong>of</strong> an accused in a serious criminaltrial to competent counsel reflects both that right to a fair trial and theconvergence from American law. <strong>The</strong> trial judge <strong>of</strong> course has a duty to ensurea fair trial and is for example entitled to withdraw the right <strong>of</strong> appearance by alawyer where satisfied that the lawyer’s incompetence or misconduct will causethe trial to miscarry.73. State law which impedes the accused’s right to silence or creates <strong>of</strong>fences basedon a legal charter that has been determined by secret evidence and a one-sidedpresentation <strong>of</strong> evidence without opportunity for the adversarial testing <strong>of</strong> issueswill continue to give rise to arguments <strong>of</strong> repugnancy with the requirements <strong>of</strong>Chapter III.74. Whilst the legislature has a proper role to curb the growth <strong>of</strong> criminalorganisations, gangs, cells and recruitment, it is important not to create scopefor political crimes that undermine democracy. <strong>The</strong>re will always be tensionsbetween human rights such as privacy, freedom <strong>of</strong> association and liberty withcriminal investigation and process. <strong>The</strong> same equitable principle <strong>of</strong> minimumrestraint necessary to protect an equitable right should apply to these tensions sothat no more is enacted than the minimum tension necessary to permit criminalinvestigation and process.

1975. Secret criminal investigation, protection <strong>of</strong> informants and vulnerable witnesses,and protection <strong>of</strong> information derived from compulsory process, should notbecome vehicles that diminish the dictates <strong>of</strong> fair process. A fair trial and acoercive new charter by exercise <strong>of</strong> judicial power including jury verdict do notpermit use <strong>of</strong> the same procedures that are necessary for detection andprevention <strong>of</strong> criminal activity. Where the balance lies will remain a tension asto what is the necessary minimum and whether it impedes the essential features<strong>of</strong> trial by jury or fair process. Any such impediment undermines publicconfidence in the integrated court system. <strong>The</strong>se matters will drive aconvergence <strong>of</strong> the content <strong>of</strong> trial by jury and fair process in both State andfederal law. This is a convergence <strong>of</strong> Australian fair process law with Americandue process law.76. Disparity in State and federal sentencing principles is also a cause foradvancement <strong>of</strong> convergence. <strong>The</strong> anathema <strong>of</strong> disparity <strong>of</strong> principle insentencing between States and differing statutory restraint for States onsentencing discretion and mandatory sentences or fixed statutory baselines forevaluation <strong>of</strong> custodial punishment do not accord with the important appellatepower in s72 <strong>of</strong> the Constitution concerning “sentences”. This appellate poweris intended to ensure unity <strong>of</strong> sentencing principles throughout theCommonwealth. Enhanced flexibility for sentencing options for those addictswho have in reality a medical problem will hopefully also become a uniformapproach in sentencing principle.K. <strong>Convergence</strong> and equity77. While the doctrines <strong>of</strong> good conscience and remedies to relieve against benefitscontrary to good conscience described as equity continue to be refined, this isanother area in which the label is arguably out dated. Principles <strong>of</strong> goodconscience should be capable <strong>of</strong> becoming a single fused body <strong>of</strong> federal lawand State law.78. Equitable remedies and equitable rights have been or are likely to be consumedinto the content <strong>of</strong> the unwritten law administered by the integrated Courtsunder the Australian Constitution. <strong>The</strong> breadth <strong>of</strong> matters within thejurisdiction <strong>of</strong> equity, although the subject <strong>of</strong> separate divisions in some State

20courts, no longer has the same clarity <strong>of</strong> distinction as a body <strong>of</strong> lawadministered by a specific court. A division in courts between federal law andState law might well be more meaningful within the structure <strong>of</strong> the AustralianConstitution.79. Whilst courts <strong>of</strong> limited jurisdiction may be constrained in their exercise <strong>of</strong>subject matter and available remedies, it is difficult to maintain that there shouldnot be scope in all courts to mould relief for legal rights and remedies asmodified by good conscience.80. All courts within the integrated courts system should be courts that administerlaw in accordance with good conscience within the subject matter <strong>of</strong> theirjurisdiction. Accordingly, whilst the debate on fusion fallacy between commonlaw and equity might continue for some time the real fusion that is continuing tooccur is the absorption <strong>of</strong> good conscience into the administration <strong>of</strong> justice bythe integrated courts system.L. <strong>Convergence</strong> and consumer law81. <strong>The</strong> recent reforms by the Australian Consumer Law enacted under theCompetition and Consumer Act 2010 are as a much as a leap into the21 st century as the Trade Practices Act 1974 was when it was introduced as amassive leap forward in the 20 th century. <strong>The</strong> full scope and impact <strong>of</strong> thestatutory guarantees that have been introduced and the significance <strong>of</strong> thefederal matter impact are likely to take some time to be fully absorbed.82. <strong>The</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> the Personal Property Securities Act 2009 as a fundamentalreform <strong>of</strong> harmonisation and its impact as a federal matter in consumercontroversies will provide significant development <strong>of</strong> consumer law. Whetherthe consumer pendulum has swung too far in the convergence <strong>of</strong> statutoryconsumer protection will inevitably require further review and tinkering as theenactment <strong>of</strong> consumer law reform is never a tool <strong>of</strong> precision. That said theseare significant reforms that advance the convergence <strong>of</strong> consumer law.83. <strong>The</strong> digital economy has also created a need for uniformity <strong>of</strong> legal doctrine toprotect consumers. <strong>The</strong> convergence <strong>of</strong> markets, platforms, products andservices as a result <strong>of</strong> the digital economy has created a rapid pace <strong>of</strong> change inendeavours to protect the interests <strong>of</strong> consumers and in particular transparency

21and accessibility. This has driven the advancement and convergence <strong>of</strong>regulatory avenues for consumer complaint law and market regulators.M. <strong>Convergence</strong> and trade law84. <strong>The</strong>re is an obvious overlap with trade law and pubic international law and onone view these legal convergence topics should be fused. However this wouldundermine the importance that trade law has played specifically in the areas <strong>of</strong>intellectual property law, competition and anti-trust law, taxation, disputeresolution, banking law, credit and payment systems, the law <strong>of</strong> insurance/re-insurance, corporate law, stock exchange, derivatives and currency markets.All these legal areas overlap and intersect on the world stage <strong>of</strong> trade. Whilston one view fiscal policies, revenue, regulatory regimes and taxation law mightall be excised as fields worthy <strong>of</strong> their own convergence pressures. <strong>The</strong>se fieldsare interdependent upon the pr<strong>of</strong>its and income derived from the tradingactivities and as regulated by domestic licensing <strong>of</strong> those businesses. <strong>The</strong>selicensing fees, like the sale <strong>of</strong> spectrum, extract a rent for those trading activitiesin Australia, similar to the rent tax extracted in relation to mineral andpetroleum resources.85. A major influence on legal convergence in the sphere <strong>of</strong> trade law is thedevelopment <strong>of</strong> regional economic blocks. <strong>The</strong>se economic blocks from theEuropean Union, to APEC create new impetus for convergence <strong>of</strong> national tradelaw. Whilst import and export imbalances may impact on domestic policy,these economic blocks require uniform laws to promote free trade, regulatecompetition and to achieve a common level <strong>of</strong> business encouragement,increased productivity and reduced protection.86. One <strong>of</strong> the most significant developments in trade law is the creation <strong>of</strong>electronic documentation, electronic processing and electronic transactions.<strong>The</strong> advancement <strong>of</strong> paperless transactions is a source <strong>of</strong> efficiency, expeditionand unification <strong>of</strong> process and business. From electronic documentary credits toelectronic bills <strong>of</strong> lading the e-commerce side <strong>of</strong> trading activities is drivingtechnologically improved payment, security and processing systems. Cloudcomputing, data-transfer and other content communication systems are also

22likely to fuel further innovation for convergence <strong>of</strong> trading activities which willcontinue the convergence <strong>of</strong> trade law.87. Another significant advancement from trade law are the model laws forenforcement <strong>of</strong> arbitral process like the New York Convention 1958 and theUNCITRAL Model Law. <strong>The</strong> Hague Convention 1971 for enforcement <strong>of</strong>foreign commercial and civil judgments arose in part out <strong>of</strong> trading activities isanother source <strong>of</strong> legal convergence.N. <strong>Convergence</strong> and maritime law88. Maritime law has always been a particularly fertile area for the growth anddevelopment <strong>of</strong> legal principle and the application <strong>of</strong> legal convergence. Fromthe historical perspective there have been numerous forms <strong>of</strong> maritime codesimplemented by countries to improve maritime commerce. Within Australiamost areas <strong>of</strong> maritime law have been the subject <strong>of</strong> legislative implementationat the domestic level <strong>of</strong> international maritime treaties or replicating UKmaritime legislation. <strong>The</strong> recent replacement <strong>of</strong> the Navigation Act 1912 withthe Navigation Act 2012 is an excellent example <strong>of</strong> the domesticimplementation <strong>of</strong> a raft <strong>of</strong> maritime model laws.89. Generally these treaties reflect international compromise between the competingState interests in the field <strong>of</strong> maritime commerce concerned, as well as havingto make allowance for the different types <strong>of</strong> legal systems within whichdomestic implementation is to operate. Accordingly there are significant gapswithin the maritime treaties that assume either an existing body <strong>of</strong> unwrittenmaritime law or an existing codification.90. <strong>The</strong> most important force in convergence <strong>of</strong> maritime law has been the UN Law<strong>of</strong> the Sea Conventions <strong>of</strong> 1958 and then 1982. <strong>The</strong> unification <strong>of</strong> legalprinciples in these Conventions address sovereign territory, territorial seas, highseas and utilization <strong>of</strong> natural resources including common heritage <strong>of</strong> mankindin relation to the resources below the sea bed. <strong>The</strong> legal convergence that thismaritime sphere <strong>of</strong> international public law has undergone is <strong>of</strong> mammothproportions.91. A major driver in development <strong>of</strong> maritime law has been the dawn <strong>of</strong>containerisation and growth <strong>of</strong> unified agreements covering multi-modal

23transportation by land, sea and air. Special purpose vessels, bulk carriers androll-on-roll-<strong>of</strong>f vessels, together with the container vessels, have improvedcargo movements, safety and security. <strong>The</strong> one stop shop freight forwardershave also impacted upon the combined transportation <strong>of</strong> cargo and unification<strong>of</strong> legal regimes for those exposed to the risk <strong>of</strong> cargo movements and thegrowth <strong>of</strong> electronic maritime transactions and under-pinning e-commerce law.92. In the world <strong>of</strong> admiralty and maritime jurisdiction there are also likely to beeconomic incentives that encourage legal convergence in line with the moreexpansive US approach to in rem remedies. This jurisdictional expansion islikely to embrace air law and in rem action attachment <strong>of</strong> aircraft, air cargo, hireand freight.O. <strong>Convergence</strong> and federation93. <strong>The</strong> centralist forces at work in the inevitable expansion <strong>of</strong> Commonwealthlegislative power are the source <strong>of</strong> a shrinking importance for the States andtheir legislative powers and bureaucracy within the federation. <strong>The</strong>convergence <strong>of</strong> international law is a powerful force in the expansion <strong>of</strong> theheads <strong>of</strong> Commonwealth legislative power and maintaining the federal balanceis more a theory <strong>of</strong> fantasy than a reality.94. True it is that matters involving Constitutional conflicts with the interests <strong>of</strong> theStates constantly try to preserve the federal balance however this an almostimpossible task given the shrinking scope <strong>of</strong> powers and the scotched reservedState powers doctrine. A glimmer <strong>of</strong> hope arises from the recognition <strong>of</strong>Constitutional institutions that must be maintained, but this cannot stop thecontinuing concentration <strong>of</strong> economic power in the Commonwealth from itsexpanded scope <strong>of</strong> legislative powers.95. This convergence <strong>of</strong> legislative power in the Commonwealth is ultimately likelyto drive referendums that revisit the role and function <strong>of</strong> State institutions. <strong>The</strong>protective balance <strong>of</strong> power objectives behind federation are arguably no longerlegitimate concerns if and when a single republic emerges.96. <strong>The</strong> need for local government input will no doubt preserve the States but notnecessarily with all the current duplication <strong>of</strong> lawmaking and governance. A

24revised federal system into a single governing politic with single elections forall states and the central governing republic seems to have to its attractions.97. This single election throughout an Australian republic every four years shouldprovide a stability and efficiency that the current federation lacks. <strong>The</strong> role <strong>of</strong>state government would remain essential for local government under a unifiedAustralian republic and the state courts could be further integrated into a singleunified court system. <strong>The</strong> forces <strong>of</strong> convergence will continue to drive bothreform <strong>of</strong> the federation and uniformity <strong>of</strong> principle applicable to Constitutionalinstitutions as well as increasing legal shifts in the federal balance.P. <strong>Convergence</strong> and the free legal networks98. <strong>The</strong> consequences <strong>of</strong> the free legal networks are <strong>of</strong> sweeping significance inachieving global legal convergence. Not only do these accessible sites facilitateunderstanding <strong>of</strong> comparative legal systems but it inevitably drives internationalcomity and the object for legal consistency.99. <strong>The</strong> accessibility and ease <strong>of</strong> access to the free legal electronic networks are amajor force in the unification <strong>of</strong> legal theory and in harmonising laws. Indeedthe availability <strong>of</strong> the workings <strong>of</strong> independent secular courts and a fearlessindependent judiciary are essential bastions for existing democracies. <strong>The</strong>sejudicial examples available over the internet create a powerful incentive fordemocratic struggles around the globe.100. Multiple language limitations remain a source <strong>of</strong> current constraint but withincreased technological development these free legal networks should becomereadily convertible into languages for all. Authenticity and security <strong>of</strong> contenton the free legal networks will also remain a matter <strong>of</strong> constraint.101. <strong>The</strong> other trend that arises from this growing global legal database is the needfor constraint in usage, selectivity and discarding. <strong>The</strong> recent focus on ananxious parade <strong>of</strong> knowledge “APK” or unctuous display <strong>of</strong> research “UDR”either in submissions or in judicial method become areas <strong>of</strong> considerableimportance for restraint. Endless citations and footnotes rapidly diminishmeaning and content. Apart from court initiated citation constraints there is thepractical need in the administration <strong>of</strong> justice to ensure that expansiveavailability <strong>of</strong> legal information does not clog the wheels in the administration

25<strong>of</strong> justice. Excessive references dull meaning and cause written works tobecome opaque to reason and an instrument <strong>of</strong> oppression.102. <strong>The</strong>se accessible sites will also give rise to refined domestic and internationalprinciples concerning the importance <strong>of</strong> transparency and accessibility <strong>of</strong> lawand <strong>of</strong> judicial process and determinations.103. <strong>The</strong> free legal internet also provides a rich pasture for the legal student,academics, scholars and continuing education <strong>of</strong> all legal practitioners.Knowledge <strong>of</strong> comparative law principles will inevitably lead to opportunitiesto advance legal convergence.Q. <strong>Convergence</strong> and judicial power104. <strong>The</strong>re is a most unhealthy trend <strong>of</strong> expansion <strong>of</strong> executive or administrativepower into the domain <strong>of</strong> subject matter that seeks to overlap judicial power.<strong>The</strong>se chameleon bodies that mimic judicial power in the resolution <strong>of</strong> disputesare arguably an anathema to the rule <strong>of</strong> law. Often these tribunals orcommissions replicate the trappings <strong>of</strong> a court and on rare occasions those whosit in these administrative bodies masquerade as if in fact judicial <strong>of</strong>ficers. It isnot appropriate for any tribunal to masquerade as a court and it is equallyinappropriate for any person sitting on a tribunal or commission to pretend to bea judge. This causes public confusion that has the potential to undermine therule <strong>of</strong> law.105. Further courts, not tribunals or commissions, deal with the crime <strong>of</strong> contempt,whether it be contempt <strong>of</strong> a body like a tribunal or a commission or whether itbe a contempt <strong>of</strong> court.106. <strong>The</strong> overlap <strong>of</strong> quasi-judicial powers by tribunals, commissions and otherauthorities is a pendulum swing <strong>of</strong> convergence that may have gone too far andthese administrative bodies may need to be more clearly contained within asphere that does not overlap with judicial power.107. Another sphere <strong>of</strong> activity that potentially undermines the propercomprehension <strong>of</strong> courts and judicial power is the borrowing by sports bodies <strong>of</strong>the impartiality and independence <strong>of</strong> real judges. To describe an administrativebody as a court is a great mischief as the courts are Constitutional institutions.

26108. No such use <strong>of</strong> the name court should be permitted by a body that is not a courtany more than those who are Chapter III justices should be given anomenclature <strong>of</strong> magistrate. Also to describe sport tribunals as being a judiciaryis questionable and at some stage this confusion should brought to an endbecause it is incompatible with our integrated court system and its exhaustivevesting <strong>of</strong> judicial power.109. Whilst the current law continues to resist the separation <strong>of</strong> powers doctrinederived from Chapter III having application to State courts the integrated courtsystem is likely to cause the re-visiting <strong>of</strong> this anomaly. Eventually aconvergence <strong>of</strong> principle in relation to State judicial power and the judicialpower <strong>of</strong> the Commonwealth requiring adherence to the separation <strong>of</strong> powersdoctrine appears essential to preserve public confidence in the integrated courtsystem. <strong>The</strong> Constitution in this regard may in the future be found to compelinstitutional uniformity including uniformity <strong>of</strong> judicial function as an essentialrequirement <strong>of</strong> the integrated court system. Arguably institutional uniformity isa necessary requirement for the preservation <strong>of</strong> the rule <strong>of</strong> law throughout theCommonwealth enforced through ss73 and 75 <strong>of</strong> the Constitution and anessential requirement to preserve the judicial independence required byChapter III.110. Another pressure that arises in the exercise <strong>of</strong> judicial power is the scope todecline exercise <strong>of</strong> properly invoked jurisdiction because <strong>of</strong> the existence <strong>of</strong>another tribunal to which Parliament has provided an avenue <strong>of</strong> review. <strong>The</strong>case-load on courts and limitations on funding have and will continue to drive atendency to vacate the fields <strong>of</strong> properly invoked jurisdiction to those otheravenues <strong>of</strong> review where appropriate redress is available. This is perhaps not atendency that should be encouraged as there is a higher principle at work in thepublic determination <strong>of</strong> disputes in real courts. That principle entrenches ageneral duty upon a court to exercise jurisdiction properly invoked.R. <strong>Convergence</strong> and appellate power111. A right <strong>of</strong> appeal in criminal matters is essential in a democracy and anyimpediments upon challenge to conviction or sentence is a questionable exercise<strong>of</strong> legislative power. It may well be that a requirement <strong>of</strong> leave to challenge

27either conviction or sentence is an incompatible interference with the integratedcourt system under the Australian Constitution. <strong>The</strong> integrated State courtsmust be free from interference or restrictions that could undermine the publicconfidence in the integrity <strong>of</strong> the courts. This integration includes courts thatare the beneficiary <strong>of</strong> the autochthonous expedient by reason <strong>of</strong> vesting <strong>of</strong>federal jurisdiction and exercise <strong>of</strong> the judicial power <strong>of</strong> the Commonwealth.112. Whilst in some civil law inquisitorial systems a court comprises three or morejudges and no right <strong>of</strong> appeal is provided, this may not be a trend <strong>of</strong>convergence that should be followed. Another questionable trend that has beenadopted is the expansion <strong>of</strong> vested appellate jurisdiction from a lower court to asingle appellate judge. Another problem is constraint upon the nature <strong>of</strong> theappellate jurisdiction although all exercise <strong>of</strong> judicial power is reviewable unders73 <strong>of</strong> the Constitution as any statutory impediment is repugnant to Chapter III.113. An appeal from a lower court to a single judge in a higher court that is an appealin the nature <strong>of</strong> a hearing de novo is far less objectionable. But the exercise <strong>of</strong> arestricted appellate jurisdiction against final orders to narrow errors <strong>of</strong> law orspecified subject matters that require leave is out <strong>of</strong> kilter with a properintegrated court system.114. This is not to say that a single appellate judge should not deal with allinterlocutory issues in an appeal, but rather the public is entitled to expect, forpreservation <strong>of</strong> their confidence, that restricted appellate rights against finalorders will bear the scrutiny <strong>of</strong> at least two and preferably three appellatejudges. An intermediate appeal in relation to individual rights that have beenfinally decided is likely to be final. It is not an uncommon occurrence that twoindependent appellate judges would decide the same case differently no doubtby reason <strong>of</strong> different emphasis or application <strong>of</strong> principle, but rarely differentlegal principle. It follows that exercise <strong>of</strong> appellate jurisdiction by three judgesis <strong>of</strong>ten more satisfactory.115. When justice is seen to be done by a proper exercise <strong>of</strong> appellate power itcreates a strengthening <strong>of</strong> public confidence in the courts. So here whilst theeconomic rationalist may welcome a single final hearing and encourageattempts to excise any power <strong>of</strong> appeal this is contrary to the integrated court

28system and Chapter III <strong>of</strong> the Australian Constitution and potentially inimical topublic confidence in the courts. Indeed convergence that denies a right <strong>of</strong>appeal from final orders are contrary to the rule <strong>of</strong> law and may be held invalid.116. Whilst appeals addressed so far are comments referrable to courts there are amyriad <strong>of</strong> tribunals, commissions and authorities from who's exercise <strong>of</strong> powera statutory right <strong>of</strong> appeal may lie to a court. It is important to understand thatno exercise <strong>of</strong> administrative or executive power by any person is beyondreview for jurisdictional error including denial <strong>of</strong> procedural fairness by anappellate court within the integrated Court system.117. <strong>The</strong> not infrequent legislative endeavours to restrict access to the courts forprerogative relief are flawed in principle and likely to be invalid. Destroyingrights <strong>of</strong> appeal or review under convergent concepts are not steps that are inharmony with the rule <strong>of</strong> law and is a confluence to be discouraged.118. Another area for concern that should be identified is the expanding attempts t<strong>of</strong>orce parties out <strong>of</strong> a court system into compulsory arbitration and to thenstultify appellate rights. In general arbitration should be based upon consensualagreement not the result <strong>of</strong> a coercive order <strong>of</strong> the court. <strong>The</strong> same consentshould generally be a pre-requisite for a court ordered expert determinations. Itshould be rare for a litigant that has properly invoked the jurisdiction <strong>of</strong> thecourt to be compelled to obtain redress outside the court system. Arbitralbodies and other alternative dispute resolution mechanisms including mediationare arguably not mechanisms that belong to the domain <strong>of</strong> the rights baseddetermination <strong>of</strong> disputes which courts must administer.119. In general no person should be deprived <strong>of</strong> access to the court system for arights based resolution <strong>of</strong> any bona fide dispute where the jurisdiction has beenproperly invoked. In answer to the economist what price for the administration<strong>of</strong> justice, it is the price <strong>of</strong> preservation <strong>of</strong> our democracy.S. <strong>Convergence</strong> and adjectival law120. <strong>The</strong>re is a constant endeavour to unify rules <strong>of</strong> evidence and procedure. This isa most constructive object as all courts in the same country should administerthe rule <strong>of</strong> law consistently and in like manner. <strong>The</strong> economist law maker hasarguably entered unbalanced weights on the scales <strong>of</strong> justice by advancing