Marketing Animals - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

Marketing Animals - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

Marketing Animals - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

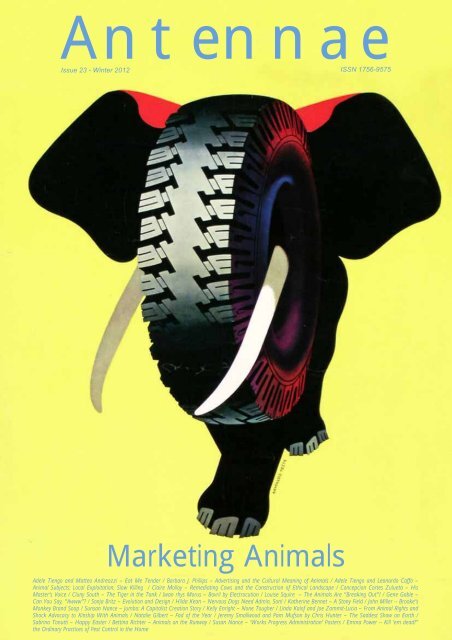

<strong>Antennae</strong><br />

Issue 23 - W<strong>in</strong>ter 2012<br />

ISSN 1756-9575<br />

<strong>Market<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Animals</strong><br />

Adele Tiengo and Matteo Andreozzi – Eat Me Tender / Barbara J. Phillips – Advertis<strong>in</strong>g and the Cultural Mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>Animals</strong> / Adele Tiengo and Leonardo Caffo –<br />

Animal Subjects: Local Exploitation, Slow Kill<strong>in</strong>g / Claire Molloy – Remediat<strong>in</strong>g Cows and the Construction <strong>of</strong> Ethical Landscape / Concepcion Cortes Zulueta – His<br />

Master’s Voice / Cluny South – <strong>The</strong> Tiger <strong>in</strong> the Tank / Iwan rhys Morus – Bovril by Electrocution / Louise Squire – <strong>The</strong> <strong>Animals</strong> Are “Break<strong>in</strong>g Out”! / Gene Gable –<br />

Can You Say, “Awww”? / Sonja Britz – Evolution and Design / Hilda Kean – Nervous Dogs Need Adm<strong>in</strong>, Son! / Kather<strong>in</strong>e Bennet – A Stony Field / John Miller -- Brooke’s<br />

1<br />

Monkey Brand Soap / Sunsan Nance – Jumbo: A Capitalist Creation Story / Kelly Enright – None Tougher / L<strong>in</strong>da Kal<strong>of</strong> and Joe Zammit-Lucia – From Animal Rights and<br />

Shock Advocacy to K<strong>in</strong>ship With <strong>Animals</strong> / Natalie Gilbert – Fad <strong>of</strong> the Year / Jeremy Smallwood and Pam Mufson by Chris Hunter – <strong>The</strong> Saddest Show on Earth /<br />

Sabr<strong>in</strong>a Tonutti – Happy Easter / Bett<strong>in</strong>a Richter – <strong>Animals</strong> on the Runway / Susan Nance – ‘Works Progress Adm<strong>in</strong>istration’ Posters / Emma Power -- Kill ‘em dead!”<br />

the Ord<strong>in</strong>ary Practices <strong>of</strong> Pest Control <strong>in</strong> the Home

<strong>Antennae</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nature</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Visual</strong> <strong>Culture</strong><br />

Editor <strong>in</strong> Chief<br />

Giovanni Aloi<br />

Academic Board<br />

Steve Baker<br />

Ron Broglio<br />

Matthew Brower<br />

Eric Brown<br />

Carol Gigliotti<br />

Donna Haraway<br />

L<strong>in</strong>da Kal<strong>of</strong><br />

Susan McHugh<br />

Rachel Poliqu<strong>in</strong><br />

Annie Potts<br />

Ken R<strong>in</strong>aldo<br />

Jessica Ullrich<br />

Advisory Board<br />

Bergit Arends<br />

Rod Bennison<br />

Helen Bullard<br />

Claude d’Anthenaise<br />

Petra Lange-Berndt<br />

Lisa Brown<br />

Rikke Hansen<br />

Chris Hunter<br />

Karen Knorr<br />

Rosemarie McGoldrick<br />

Susan Nance<br />

Andrea Roe<br />

David Rothenberg<br />

Nigel Rothfels<br />

Angela S<strong>in</strong>ger<br />

Mark Wilson & Bryndís Snaebjornsdottir<br />

Global Contributors<br />

João Bento & Catar<strong>in</strong>a Fontoura<br />

Sonja Britz<br />

Tim Chamberla<strong>in</strong><br />

Concepción Cortes<br />

Lucy Davis<br />

Amy Fletcher<br />

Katja Kynast<br />

Christ<strong>in</strong>e Marran<br />

Carol<strong>in</strong>a Parra<br />

Zoe Peled<br />

Julien Salaud<br />

Paul Thomas<br />

Sabr<strong>in</strong>a Tonutti<br />

Johanna Willenfelt<br />

Copy Editor<br />

Maia Wentrup<br />

Front Cover Image: Orig<strong>in</strong>al image - Pirelli, Atlante, 1954 © Pirelli<br />

2

EDITORIAL<br />

ANTENNAE ISSUE 23<br />

T<br />

his issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>Antennae</strong> was developed around the idea that advertis<strong>in</strong>g can be much more than<br />

a pivotal market<strong>in</strong>g tool <strong>in</strong> capitalist societies. Over the past few years, through the <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

popularity <strong>of</strong> social networks advertis<strong>in</strong>g strategies have more and more come to play a pivotal<br />

role <strong>in</strong> communication and can be understood as a cultural thermometer <strong>of</strong> our identities and desires.<br />

<strong>The</strong> conspicuous presence <strong>of</strong> animals <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g is therefore a phenomenon that deserves study; it<br />

is not a new phenomenon <strong>in</strong> itself but it is one that nonetheless demands renewed attention and<br />

scrut<strong>in</strong>y through a human-animal studies lens. Whether photographed, illustrated, animated or filmed<br />

the ambivalent presence <strong>of</strong> the animal, <strong>in</strong>itially seems to facilitate the delivery <strong>of</strong> consumeristic<br />

messages. However, th<strong>in</strong>gs are much more complex. What does the animal sell to us and what do we<br />

effectively buy through these <strong>in</strong>stances <strong>of</strong> visual consumption? What role does the animal play <strong>in</strong> the<br />

persuasions processes enacted by advertisements?<br />

In the attempt to provide some answers to these questions and more, besides a traditional call<br />

for academic papers, <strong>Antennae</strong> also solicited short commentaries on advertisements chosen by our<br />

readers and contributors. <strong>The</strong> colourful variety <strong>of</strong> examples submitted contributes to the outl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> an<br />

extremely diverse range <strong>of</strong> animal appearances <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g greatly vary<strong>in</strong>g on the grounds <strong>of</strong> what is<br />

to be sold and which target audiences are to persuade. <strong>The</strong>se shorter entries have been <strong>in</strong>terposed<br />

between longer and more complex analyses <strong>of</strong> specific animal presences <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g. One <strong>of</strong> the<br />

unexpected result gathered from the collection <strong>of</strong> the excellent submissions we received, highlights a<br />

perhaps not too surpris<strong>in</strong>g, current, overrid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terest for mammals aga<strong>in</strong>st any other animal group.<br />

Anthropomorphism may be an <strong>in</strong>evitable expedient essential to the success <strong>of</strong> the identification<br />

process ly<strong>in</strong>g at the core <strong>of</strong> all advertis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tend<strong>in</strong>g to sell us commodities. This is rather well<br />

demonstrated through the publication <strong>of</strong> a portfolio <strong>of</strong> v<strong>in</strong>tage adverts with which this issue comes to a<br />

close. For this essential contribution we have to thank Nigel Rothfels who on a warm June afternoon <strong>in</strong><br />

2011 walk<strong>in</strong>g lazily around the streets <strong>of</strong> Zurich came across a very unusual archive. As Nigel recalls, “I<br />

was <strong>in</strong> the city to attend a small conference on science and before long, I found myself star<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to<br />

the w<strong>in</strong>dows <strong>of</strong> the Swiss National Bank! A quite fasc<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g exhibit had been organized <strong>in</strong> the w<strong>in</strong>dows<br />

by staff at the Museum für Gestaltung Zürich focus<strong>in</strong>g on the history <strong>of</strong> animals appear<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g<br />

posters. I went from w<strong>in</strong>dow to w<strong>in</strong>dow enjoy<strong>in</strong>g the posters and tak<strong>in</strong>g pictures. Through the generosity<br />

<strong>of</strong> Dr. Bett<strong>in</strong>a Richter and Allesia Cont<strong>in</strong> at the Museum, we are now able to br<strong>in</strong>g a selection <strong>of</strong> this<br />

rarely seen and remarkable collection to <strong>Antennae</strong>’s readers”.<br />

Besides consider<strong>in</strong>g a range <strong>of</strong> well known and lesser know advertisements, this issue also looks<br />

at the more ethically driven consideration <strong>of</strong> the use <strong>of</strong> animal imagery <strong>in</strong> the advertisements<br />

produced by animal advocacy and conservation organisations through a thought-provok<strong>in</strong>g piece by<br />

Joe Zammit-Lucia and L<strong>in</strong>da Kal<strong>of</strong>, whilst an <strong>in</strong>terview with creative teams at Young & Rubicam<br />

Chicago demonstrates how the presence <strong>of</strong> animals <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g can be used to the advantage <strong>of</strong><br />

animals through some astonish<strong>in</strong>gly simple but impressive communicational <strong>in</strong>ventiveness.<br />

Lastly I would like to take the opportunity to thank all <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> this issue <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Antennae</strong>.<br />

Giovanni Aloi<br />

Editor <strong>in</strong> Chief <strong>of</strong> <strong>Antennae</strong> Project<br />

3

CONTENTS<br />

ANTENNAE ISSUE 23<br />

6 Eat Me Tender<br />

Love can be dangerous when it comes to cook<strong>in</strong>g. In this image, the evidence that a ‘lover’ wants to possess his woman just like a ‘meat lover’ wants to eat his steak is<br />

exposed <strong>in</strong> a grotesque way. Sexist discrim<strong>in</strong>ation and animal exploitation are here associated to ‘love’, understood as an abuse mitigated by tenderness and care <strong>in</strong> the act<br />

<strong>of</strong> possess<strong>in</strong>g and kill<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Text by Adele Tiengo and Matteo Andreozzi<br />

9 Advertis<strong>in</strong>g and the Cultural Mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>Animals</strong><br />

One explanation for the proliferation <strong>of</strong> animal trade characters <strong>in</strong> current advertis<strong>in</strong>g practice proposes that they are effective communication tools because they can be used<br />

to transfer desirable cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs to products with which they are associated. <strong>The</strong> first step <strong>in</strong> exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g what messages these animals communicate is to explore the<br />

common cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs that they embody. This paper presents a qualitative analysis <strong>of</strong> the common themes found <strong>in</strong> the cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> four animal characters. In<br />

addition, it demonstrates a method by which cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs can be elicited. <strong>The</strong> implications <strong>of</strong> this method for advertis<strong>in</strong>g research and practice are discussed.<br />

Text by Barbara J. Phillips<br />

20 Animal Subjects: Local Exploitation, Slow Kill<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>The</strong> city <strong>of</strong> Milan will host Expo 2015, with the theme “Feed<strong>in</strong>g the Planet. Energy for Life”. In view <strong>of</strong> this occasion, the <strong>in</strong>terest for cul<strong>in</strong>ary tradition and the global challenge<br />

<strong>of</strong> food security is rapidly grow<strong>in</strong>g. Farm<strong>in</strong>g and livestock rais<strong>in</strong>g traditions plays a major role <strong>in</strong> Italy, homeland <strong>of</strong> the worldwide renowned Slow Food.<br />

Text by Adele Tiengo and Leonardo Caffo<br />

23 Remediat<strong>in</strong>g Cows and the Construction <strong>of</strong> Ethical Landscape<br />

Concern about the impact <strong>of</strong> livestock on the environment has generated debates about how best to manage dairy farm<strong>in</strong>g practices. Soil erosion and compaction and loss <strong>of</strong><br />

biodiversity from graz<strong>in</strong>g and silage production, ammonia and methane emissions, as well as high levels <strong>of</strong> water consumption, have all been identified as direct effects on the<br />

environment from dairy farm<strong>in</strong>g activity. [i] Whilst the issues have been well reported <strong>in</strong> the press, there has been little <strong>in</strong> the way <strong>of</strong> imagery to accompany the environmental<br />

critique <strong>of</strong> milk production. Instead, much <strong>of</strong> the popularly available imagery <strong>of</strong> dairy farm<strong>in</strong>g has been generated by advertis<strong>in</strong>g which cont<strong>in</strong>ues to deploy culturally-specific<br />

visions <strong>of</strong> contented cows <strong>in</strong> rural landscapes.<br />

Text by Claire Molloy<br />

28 His Master’s Voice<br />

A white dog with brown ears sits <strong>in</strong> front <strong>of</strong> a gramophone, head directed to its brass-horn and slightly tilted to one side. <strong>The</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g was purchased <strong>in</strong> 1899, along<br />

with its full copyright, by the emerg<strong>in</strong>g Gramophone Company from the artist Francis Barraud.<br />

Text by Concepcion Cortes Zulueta<br />

31 <strong>The</strong> Tiger <strong>in</strong> the Tank<br />

Despite the complexities and <strong>in</strong>constancies <strong>of</strong> the human-animal relationship non-human animals [1] have been <strong>in</strong>timately <strong>in</strong>terwoven with<strong>in</strong> human culture for thousands <strong>of</strong><br />

years. Representations <strong>of</strong> animals exist across many mediums, with roots clearly visible <strong>in</strong> Palaeolithic cave pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>gs and early carv<strong>in</strong>gs, evolv<strong>in</strong>g human language, music and<br />

drama, and narrative fables and folk stories. Unsurpris<strong>in</strong>gly then animal representations cont<strong>in</strong>ue to be rife throughout our modern lives and across much popular media.<br />

Text by Cluny South<br />

39 Bovril by Electrocution<br />

I first came across this illustration whilst brows<strong>in</strong>g through Leonard de Vries’s fasc<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g collection, Victorian Advertis<strong>in</strong>g, about twelve years ago. I was look<strong>in</strong>g for someth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

else at the time – examples <strong>of</strong> late Victorian electric belt advertisements as part <strong>of</strong> a project on n<strong>in</strong>eteenth-century medical electricity. Instead, this one jumped out <strong>of</strong> the<br />

page at me.<br />

Text by Iwan Rhys Morus<br />

42 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Animals</strong> Are “Break<strong>in</strong>g Out”!<br />

This paper explores recent TV adverts <strong>in</strong> which the animals portrayed come to appear before us <strong>in</strong> new ways. Gone are cosy images <strong>of</strong> chimpanzees play<strong>in</strong>g house, wear<strong>in</strong>g<br />

flat-caps and frocks, and pour<strong>in</strong>g cups <strong>of</strong> tea. <strong>The</strong> animals are break<strong>in</strong>g out! Mary, the cow (Muller yoghurt), is “set free” on a beach to fulfil her dream <strong>of</strong> becom<strong>in</strong>g a horse.<br />

More cows (Anchor butter) have taken charge <strong>of</strong> the dairy.<br />

Text by Louise Squire<br />

49 Can You Say, “Awww”?<br />

<strong>Animals</strong> have long been a regular theme <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g, especially when anthropomorphized. Except for obvious ties to products like dog food and pet products, animals<br />

usually have noth<strong>in</strong>g to do with the goods or services advertised, but we connect with them and the products nonetheless, and we get a good feel<strong>in</strong>g when a company is<br />

associated with cute animals.<br />

Text by Gene Gable<br />

51 Evolution and Design<br />

<strong>The</strong> animal as sign has a long evolutionary history, but with the onset <strong>of</strong> cultural modernity it began to assume new semiotic forms. Foucault describes a new field <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>creased visibility that emerged <strong>in</strong> the eighteenth century which gave rise to a complex semiotic system with<strong>in</strong> which the sign began to take on a life <strong>of</strong> its own. If images<br />

could be regarded as liv<strong>in</strong>g organisms, how could this affect their representational values <strong>in</strong> society? And, what are the implications for the lives and representation <strong>of</strong> animals?<br />

Text by Sonja Britz<br />

61 Nervous Dogs Need Adm<strong>in</strong>, Son!<br />

This advert comes from a British magaz<strong>in</strong>e <strong>The</strong> Tail Wagger, October 1940. <strong>The</strong> Tail- Waggers Club had been founded <strong>in</strong> 1928 to promote dog welfare stat<strong>in</strong>g, ‘<strong>The</strong> love<br />

<strong>of</strong> animals, and especially <strong>of</strong> dogs, is <strong>in</strong>herent <strong>in</strong> nearly all Britishers’ and by 1930 numbered some 300,000 members. [i] All dogs were eligible for membership, not just those<br />

from established breeds. By July 1930 it had become a general legal requirement that all dogs should wear collars and the club and magaz<strong>in</strong>e endorsed such measures. [ii]<br />

Text by Hilda Kean<br />

64 A Stony Field<br />

Brand representations proliferate reflexive identities <strong>of</strong> their producers and consumers. <strong>The</strong>se self-advertisements re<strong>in</strong>scribe commodified identities reproductively back onto the<br />

subjects and objects – the represented figures – <strong>of</strong> consumption. In this paper I argue that the cooption <strong>of</strong> identity politics by mult<strong>in</strong>ational corporations like Stonyfield Farm,<br />

Inc. operates with<strong>in</strong> material and virtual doma<strong>in</strong>s that conceal fetishized processes <strong>of</strong> consumption.<br />

Text by Kather<strong>in</strong>e Bennett<br />

80 Brooke’s Monkey Brand Soap<br />

Brooke’s Monkey Brand Soap was a common, even iconic, presence <strong>in</strong> the pages <strong>of</strong> late n<strong>in</strong>eteenth-century illustrated newspapers <strong>in</strong> Brita<strong>in</strong>. Barely an issue <strong>of</strong> the London<br />

Illustrated News, <strong>The</strong> Graphic or <strong>The</strong> Sketch passed without a full or half page spread <strong>of</strong> Brooke’s ubiquitous monkey, arrayed <strong>in</strong> one <strong>of</strong> its many baffl<strong>in</strong>g guises:<br />

promenad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> top hat and tails, juggl<strong>in</strong>g cook<strong>in</strong>g pots <strong>in</strong> a jester’s get-up, strumm<strong>in</strong>g a mandol<strong>in</strong> on the moon, destitute and begg<strong>in</strong>g by the side <strong>of</strong> the road, kneel<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

accept a medal from a glamorous Frenchwoman, career<strong>in</strong>g along on a bicycle with feet on the handle-bars, cl<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g precariously to a ship’s mast, carefully polish<strong>in</strong>g the family<br />

ch<strong>in</strong>a and here <strong>in</strong> 1891, slid<strong>in</strong>g gleefully down the banisters with legs spread wide and the h<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> a smile while two neat Victorian children watch calmly on.<br />

Text by John Miller<br />

4

83 Jumbo: A Capitalist Creation Story<br />

Today, a pr<strong>of</strong>usion <strong>of</strong> non-human animals <strong>in</strong>habit the world <strong>of</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g. Consumers see some <strong>of</strong> them <strong>in</strong> person and some as brand icons, team mascots, and other moregeneric<br />

endorsers <strong>of</strong> consumption (sometimes their own consumption, like pig characters decorat<strong>in</strong>g BBQ restaurants or matronly cows on dairy product packag<strong>in</strong>g)<br />

embellish<strong>in</strong>g countless products, services and enterta<strong>in</strong>ments. This zoological cornucopia provides a naturaliz<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>k to the non-human world, promis<strong>in</strong>g us that to absorb<br />

advertis<strong>in</strong>g messages and spend is to participate <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>evitable and emotionally authentic activity because, as the belief goes, animals don’t lie (Shuk<strong>in</strong> 2009, 3-5).<br />

Text by Susan Nance<br />

95 None Tougher<br />

Rh<strong>in</strong>oceroses are rarely anthropomorphized mak<strong>in</strong>g this American magaz<strong>in</strong>e advertisement from the 1950s an unusual specimen. Armstrong, a rubber and tire company,<br />

found the tough exterior <strong>of</strong> rh<strong>in</strong>oceroses the prime comparison for its most durable automobile tires, dubbed “Rh<strong>in</strong>o-Flex.”<br />

Text by Kelly Enright<br />

98 From Animal Rights and Shock Advocacy to K<strong>in</strong>ship with <strong>Animals</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> visual cultures manifested <strong>in</strong> the advertis<strong>in</strong>g and communication activities <strong>of</strong> animal rights activists and those concerned with the conservation <strong>of</strong> species may<br />

be counter-productive, creat<strong>in</strong>g an ever-<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g cultural distance between the human and the animal. By cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g to position animals as subjugated,<br />

exploitable others, or as creatures that belong <strong>in</strong> a romanticized ‘nature’ separate from the human, communications campaigns may achieve effects that are<br />

contrary to those desired. <strong>The</strong> unashamed, cheaply voyeuristic nature <strong>of</strong> shock imagery may w<strong>in</strong> headl<strong>in</strong>es while worsen<strong>in</strong>g the overall position <strong>of</strong> the animal <strong>in</strong><br />

human culture. We <strong>of</strong>fer an alternative way <strong>of</strong> th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g about visual communication concern<strong>in</strong>g animals – one that is focused on enhanc<strong>in</strong>g a sense <strong>of</strong> k<strong>in</strong>ship<br />

with animals. Based on empirical evidence, we suggest that cont<strong>in</strong>ued progress both <strong>in</strong> conservation and <strong>in</strong> animal rights does not depend on cont<strong>in</strong>ued<br />

castigation <strong>of</strong> the human but rather on embedd<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> our cultures the type <strong>of</strong> human-animal relationship on which positive change can be built.<br />

Text by Joe Zammit-Lucia and L<strong>in</strong>da Kal<strong>of</strong><br />

112 Fad <strong>of</strong> the Year<br />

At the end <strong>of</strong> 2010 one <strong>of</strong> the UK’s commercial television channels, ITV, selected twenty <strong>of</strong> the most popular TV adverts from the year and entered them <strong>in</strong> to their own<br />

competition to f<strong>in</strong>d the television ‘Ad <strong>of</strong> the Year’. <strong>The</strong> w<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g advert was one featur<strong>in</strong>g a rescue dog called Harvey who is <strong>in</strong> kennels, hop<strong>in</strong>g somebody will come along and<br />

adopt him.<br />

Text by Natalie Gilbert<br />

114 <strong>The</strong> Saddest Show on Earth<br />

S<strong>in</strong>ce 1884, children across the United States have been dazzled by the sequ<strong>in</strong>ed wonders <strong>of</strong> the R<strong>in</strong>gl<strong>in</strong>g Bros. Circus. For many a youngster the spectacle <strong>of</strong> costumed<br />

elephants perform<strong>in</strong>g myriad tricks under the big top is a highlight <strong>of</strong> the show. Yet the bright spotlight <strong>of</strong> the center r<strong>in</strong>g casts a dark shadow across this American <strong>in</strong>stitution.<br />

Persistent allegations <strong>of</strong> elephant abuse have trailed the travell<strong>in</strong>g show for years.<br />

Text and <strong>in</strong>terview questions to Jeremy Smallwood and Pam Mufson by Chris Hunter<br />

120 Happy Easter<br />

Even if we are talk<strong>in</strong>g about this image as an “advertisement”, it is clear that its scope is not bus<strong>in</strong>ess, but to <strong>in</strong>form and raise consciousness about the slaughter<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

animals. <strong>The</strong> message itself is rather peculiar: it’s obviously about animals, but without <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g any image <strong>of</strong> them <strong>in</strong> the picture. If a contradiction exists, it has noth<strong>in</strong>g to do<br />

with the message conveyed by the advertisement, but rather with ambiguous attitudes <strong>of</strong> humans towards animals. In this case, it’s the lambs who are not portrayed <strong>in</strong> the<br />

advertisement.<br />

Text by Sabr<strong>in</strong>a Tonutti<br />

123 <strong>Animals</strong> on the Runway<br />

<strong>The</strong> discussion <strong>of</strong> animals <strong>in</strong> graphic art has radically changed s<strong>in</strong>ce about 1950. In contemporary performances and <strong>in</strong>stallations, even liv<strong>in</strong>g animals are displayed, which<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten leads to ethical discussions. Recent work, however, reflects a new societal view <strong>of</strong> animals: A strictly anthropocentric view has had its day, now animals have come to be<br />

seen as equal creatures and have emancipated themselves <strong>in</strong> artistic representation.<br />

Text by Bett<strong>in</strong>a Richter<br />

132 ‘Works Progress Adm<strong>in</strong>istration’ Posters<br />

In 1933 and 1934, as part <strong>of</strong> the “New Deal” economic plan for the United States, President Frankl<strong>in</strong> Roosevelt’s adm<strong>in</strong>istration created a new federal agency called the<br />

Works Progress Adm<strong>in</strong>istration (WPA) to hire artists to document and promote American cultural life.<br />

Text by Susan Nance<br />

136 Kill ‘em dead!: the Ord<strong>in</strong>ary Practices <strong>of</strong> Pest Control <strong>in</strong> the Home<br />

In recent years critical animal geographies have po<strong>in</strong>ted to dearth <strong>of</strong> stories about the small, the microscopic, the slimy and the abject. <strong>The</strong> exoskeleton, though pa<strong>in</strong>fully<br />

present to anyone bitten by a bedbug or disgusted by a cockroach, has been all but absent <strong>in</strong> dom<strong>in</strong>ant animal geographies. Death and the kill<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> animals is a further<br />

notable absence. However, this scholarly absence is not parallel with<strong>in</strong> the popular imag<strong>in</strong>ation, where cockroaches, files and dust mites loom large at the centre <strong>of</strong> a<br />

homemak<strong>in</strong>g war focused on the eradication <strong>of</strong> house pests.<br />

Text by Emma Power<br />

5

S<br />

<strong>in</strong>ce the Sixties, ec<strong>of</strong>em<strong>in</strong>ist philosophical<br />

th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g has been underl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the strong<br />

connection between sexist discrim<strong>in</strong>ation,<br />

exploitation <strong>of</strong> nonhuman animals, and abuse <strong>of</strong><br />

natural resources. <strong>The</strong>se three phenomena have<br />

been seen as so deeply <strong>in</strong>terconnected, both<br />

conceptually and historically, that they can be<br />

adequately understood and handled only as a<br />

s<strong>in</strong>gle question. What the ec<strong>of</strong>em<strong>in</strong>ists state –<br />

and the image presented <strong>in</strong> this advert confirms<br />

– is that <strong>in</strong> Western patriarchal civilization,<br />

women, nonhuman animals, and the<br />

environment are categories related to ‘animated<br />

properties’, or ‘mobile goods’.<br />

How should these logically fallacious and<br />

discrim<strong>in</strong>atory messages be handled, criticized,<br />

and discouraged? <strong>The</strong> ec<strong>of</strong>em<strong>in</strong>ist philosopher<br />

Val Plumwood suggests to contrast the<br />

patriarchal conceptual framework through a<br />

careful work <strong>of</strong> revaluation, celebration, and<br />

defense <strong>of</strong> what male dom<strong>in</strong>ion subdues. On<br />

the one hand, dichotomical metaphors<br />

underrate the fem<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e as related to corporeality,<br />

emotions, <strong>in</strong>tuitiveness, cooperation, care, and<br />

sympathy; on the other hand, the mascul<strong>in</strong>e is<br />

celebrated as related to opposed concept,<br />

such as rationality, <strong>in</strong>tellect, competition,<br />

dom<strong>in</strong>ion, and apathy (Plumwood, 1992).<br />

6<br />

EAT ME TENDER<br />

Love can be dangerous when it comes to cook<strong>in</strong>g. In this image, the evidence that a ‘lover’ wants to possess his<br />

woman just like a ‘meat lover’ wants to eat his steak is exposed <strong>in</strong> a grotesque way. Sexist discrim<strong>in</strong>ation and<br />

animal exploitation are here associated to ‘love’, understood as an abuse mitigated by tenderness and care <strong>in</strong> the<br />

act <strong>of</strong> possess<strong>in</strong>g and kill<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Text by Adele Tiengo and Matteo Andreozzi<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the most powerful ec<strong>of</strong>em<strong>in</strong>ist approach<br />

to the issue <strong>of</strong> animal exploitation as a practice<br />

focused on – but not restricted to – food is Carol<br />

Adams’ <strong>The</strong> Sexual Politics <strong>of</strong> Meat. Published <strong>in</strong><br />

1990, Adams’ book comb<strong>in</strong>es the author’s<br />

experience as a fem<strong>in</strong>ist activist and her<br />

academic researches to formulate the l<strong>in</strong>k<br />

between the perception <strong>of</strong> nonhuman animals<br />

and women as ‘consumable bodies’, <strong>of</strong>fered to<br />

men’s pleasure. Adams suggests that both<br />

women and animals are victims <strong>of</strong> a process <strong>of</strong><br />

objectification, fragmentation, and<br />

consumption, especially <strong>in</strong> visual, textual, and<br />

discursive texts. Through metaphor, a subject is<br />

objectified, then fragmented and separated<br />

from its ontological mean<strong>in</strong>g, and consumed as<br />

an object, exist<strong>in</strong>g only through what it<br />

represents. In the Meat Lovers advertisement, the<br />

woman/cow is an object <strong>of</strong> consumption and<br />

the representation <strong>of</strong> the patriarchal idea <strong>of</strong> love<br />

as dom<strong>in</strong>ion and possession.<br />

Many are also the analogies between Adams’<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigation and Derrida’s<br />

carnophallogocentrism. Derrida uses this<br />

neologism to <strong>in</strong>dicate the predom<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>of</strong><br />

rationality, mascul<strong>in</strong>ity, and carnivorous habits. In<br />

his <strong>in</strong>terview ‘Eat<strong>in</strong>g Well’, he clarifies this po<strong>in</strong>t<br />

admitt<strong>in</strong>g that women and vegetarians are

actually ethical, juridical and political subjects,<br />

as well as men and meat eaters. However, this is<br />

a recent achievement, and still «authority […] is<br />

attributed to the man (homo and vir) rather than<br />

to the woman, and to the woman rather than to<br />

the animal». And <strong>in</strong> fact, Derrida asks, how many<br />

possibilities are there that a head <strong>of</strong> State<br />

publicly and exemplarily declares himself – or<br />

herself – to be a vegetarian? (Derrida, 'Eat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Well', or the Calculation <strong>of</strong> the Subject: An<br />

Interview with Jacques Derrida 1991, 114).<br />

Both identify meat eat<strong>in</strong>g and maleness<br />

as crucial elements <strong>in</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g who is a<br />

subject. In particular, Derrida states that there are<br />

three fundamental conditions to recognize a<br />

subject as such, at least <strong>in</strong> Western cultures:<br />

La Capann<strong>in</strong>a<br />

Amanti della Carne (Meat Lovers), advert La Capann<strong>in</strong>a<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g «a meat eater, a man, and an<br />

authoritative, speak<strong>in</strong>g self» (Calarco qtd <strong>in</strong><br />

Adams, <strong>The</strong> Sexual Politics <strong>of</strong> Meat 1990, 6).<br />

Adams develops this idea <strong>in</strong> a far more detailed<br />

way. In particular she focuses on the implications<br />

<strong>of</strong> the perception <strong>of</strong> animal/female bodies as<br />

‘consummable’ through butchery and rape,<br />

underl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the evidences <strong>of</strong> this analogy <strong>in</strong><br />

images, commercials, menu covers, and articles<br />

7<br />

that use the female body to attract the male<br />

meat eaters. In the case <strong>of</strong> the advertisement<br />

here presented, rigorously male meat eaters are<br />

<strong>in</strong>vited to consume their love for a steak on a<br />

bed <strong>of</strong> lettuce.<br />

However, rather than aggressive and<br />

pornographic, this k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> love seems tender and<br />

devoted. <strong>The</strong> cow’s head is ridiculously put on<br />

the body <strong>of</strong> a sleep<strong>in</strong>g woman and a man<br />

embraces her. <strong>The</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> the advertisement is to<br />

arouse a k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> tenderness for the animal killed<br />

without putt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to question the meat eater’s<br />

virility. In fact, the tenderness here displayed is<br />

the one that follows the sexual <strong>in</strong>tercourse<br />

between husband and wife, maybe. Curiously<br />

enough, it is the beloved steak that plays here<br />

the role <strong>of</strong> the absent referent. Both the woman<br />

and the cow are visually present <strong>in</strong> the image,<br />

but the object <strong>of</strong> the advertisement – meat – is<br />

only textually summoned. In fact, the proposed<br />

idea is that meat eat<strong>in</strong>g is a behaviour <strong>of</strong> car<strong>in</strong>g<br />

because the woman/cow wants to be object <strong>of</strong><br />

that k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> ‘tenderness’, mean<strong>in</strong>g that she wants<br />

to be eaten/consumed.<br />

<strong>The</strong> scene is not one <strong>of</strong> seduction, but <strong>of</strong>

marital love. Carol Adams clearly expla<strong>in</strong>s how<br />

the sexual politics <strong>of</strong> meat beg<strong>in</strong>s with<strong>in</strong> the<br />

exploitation <strong>of</strong> the reproductive functions <strong>of</strong><br />

female animals. Liv<strong>in</strong>g alone milk and eggs –<br />

which are products <strong>of</strong> maternity –, the majority <strong>of</strong><br />

meat comes from adult females and their<br />

babies. Female nonhuman animals are<br />

exploited to satisfy human appetites both when<br />

they are alive and when they are dead, while<br />

male animals are used much less <strong>in</strong> the food<br />

References<br />

Adams, Carol J. <strong>The</strong> Sexual Politics <strong>of</strong> Meat. Twentieth<br />

Anniversary Edition (2010). New York : Cont<strong>in</strong>uum, 1990.<br />

Derrida, Jacques. "'Eat<strong>in</strong>g Well', or the Calculation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Subject: An Interview with Jacques Derrida" <strong>in</strong> Who Comes<br />

After the Subject, edited by Eduardo Cadava, Peter Connor<br />

and Jean-Luc Nancy, 96-119. New York and London:<br />

Routledge, 1991.<br />

Plumwood, Val. "Fem<strong>in</strong>ism and Ec<strong>of</strong>em<strong>in</strong>ism: Beyond the<br />

Dualistic Assumptions <strong>of</strong> Women, Men, and <strong>Nature</strong>." <strong>The</strong><br />

Ecologist 22, no. 1 (January/February 1992).<br />

8<br />

<strong>in</strong>dustry, because they don’t produce anyth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g their lives and their meat is considered as<br />

less succulent and tasty. In an analogous way,<br />

female human animals are exploited ma<strong>in</strong>ly<br />

when they are alive for their sexual and<br />

reproductive function and, basically, to satisfy<br />

men’s pleasure. <strong>The</strong> Meat lovers image makes it<br />

clear that not much has changed, s<strong>in</strong>ce the<br />

Sixties: females <strong>of</strong> all species are ‘objects’ <strong>of</strong> love<br />

and properties <strong>of</strong> men.<br />

Adele Tiengo is a Ph.D. student <strong>in</strong> Foreign Languages, Literatures,<br />

and <strong>Culture</strong>s at the University <strong>of</strong> Milan (Italy), where she graduated<br />

<strong>in</strong> 2012 with a thesis on the relationship between literature and<br />

ethics <strong>in</strong> the animal question. In 2011 she spent a period as a<br />

visit<strong>in</strong>g researcher at the University <strong>of</strong> Alcalà (Spa<strong>in</strong>), thanks to the<br />

Susan Fenimore Cooper scholarship. She is currently carry<strong>in</strong>g on<br />

her research activities <strong>in</strong> ecocriticism.<br />

Matteo Andreozzi is a PhD student <strong>in</strong> Philosophy at University <strong>of</strong><br />

Milan, Italy. His research is ma<strong>in</strong>ly on Environmental Ethics and<br />

Movements, with a special focus on the analysis and the<br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic value concept. He is author <strong>of</strong> the<br />

book Verso Una Prospettiva Ecocentrica. Ecologia Pr<strong>of</strong>onda e<br />

Pensiero a Aete[Head<strong>in</strong>g Toward an Ecocentric M<strong>in</strong>dset. Deep<br />

Ecology and Reticular Th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g], 2011 and editor <strong>of</strong> the book<br />

Etiche dell’Ambiente. Voci e Prospettive [Environmental Ethics.<br />

Voices and Perspectives], 2012. He is also representative member<br />

<strong>of</strong> ENEE (European Network for Environmental Ethics) and MAnITA<br />

(M<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Animals</strong> Italy) and member <strong>of</strong> ISEE (International Society<br />

for Environmental Ethics) and ESFRE (European Forum for the Study<br />

<strong>of</strong> Religion and the Environment). For further <strong>in</strong>formation please<br />

visit http://www.matteoandreozzi.it or<br />

http://unimi.academia.edu/MatteoAndreozzi.

A<br />

merican popular culture has quietly<br />

become <strong>in</strong>habited by all sorts <strong>of</strong> talk<strong>in</strong>g<br />

animals and danc<strong>in</strong>g products that are<br />

used by advertisers to promote their brands.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se creatures, called trade characters, are<br />

fictional, animate be<strong>in</strong>gs, or animated objects,<br />

that have been created for the promotion <strong>of</strong> a<br />

product, service, or idea (Phillips 1996).<br />

Commercials with these characters score above<br />

average <strong>in</strong> their ability to change brand<br />

preference (Stewart and Furse 1986). It appears,<br />

then, that trade characters can be effective<br />

communication tools. However, it is unclear why<br />

this is so. Although trade characters are popular<br />

with advertisers and consumers, their role <strong>in</strong><br />

communicat<strong>in</strong>g the advertis<strong>in</strong>g message has<br />

been generally taken for granted without<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigation. It has been<br />

hypothesized that there are several reasons why<br />

advertisers use trade characters: to attract<br />

attention, enhance identification <strong>of</strong> and memory<br />

ADVERTISING AND THE<br />

CULTURAL MEANING<br />

OF ANIMALS<br />

One explanation for the proliferation <strong>of</strong> animal trade characters <strong>in</strong> current advertis<strong>in</strong>g practice proposes that they<br />

are effective communication tools because they can be used to transfer desirable cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs to products<br />

with which they are associated. <strong>The</strong> first step <strong>in</strong> exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g what messages these animals communicate is to<br />

explore the common cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs that they embody. This paper presents a qualitative analysis <strong>of</strong> the<br />

common themes found <strong>in</strong> the cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> four animal characters. In addition, it demonstrates a method<br />

by which cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs can be elicited. <strong>The</strong> implications <strong>of</strong> this method for advertis<strong>in</strong>g research and practice<br />

are discussed.<br />

Text by Barbara J. Phillips<br />

9<br />

for a product, and achieve promotional<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>uity (Phillips 1996). However, one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

most important reasons for the use <strong>of</strong> trade<br />

characters <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g may be that they can<br />

be used to transfer desired mean<strong>in</strong>gs to the<br />

products with which they are associated. By<br />

pair<strong>in</strong>g a trade character with a product,<br />

advertisers can l<strong>in</strong>k the personality and cultural<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the character to the product <strong>in</strong> the<br />

m<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> consumers. This creates a desirable<br />

image, or mean<strong>in</strong>g, for the product. <strong>The</strong> first step<br />

<strong>in</strong> support<strong>in</strong>g this explanation <strong>of</strong> trade character<br />

communication is to show that these characters<br />

do embody common cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs that can<br />

be l<strong>in</strong>ked to products. Research has shown<br />

that animal characters are one <strong>of</strong> the most<br />

commonly used trade character types <strong>in</strong> current<br />

advertis<strong>in</strong>g practice (Callcott and Lee 1994).<br />

<strong>Animals</strong> have long been viewed as standard<br />

symbols <strong>of</strong> human qualities (Neal 1985; Sax<br />

1988). For example, <strong>in</strong> American culture,

"everyone" knows that a bee<br />

symbolizes<strong>in</strong>dustriousness, a dove represents<br />

peace, and a fox embodies cunn<strong>in</strong>g (Rob<strong>in</strong><br />

1932). It is likely that advertisers use animal<br />

characters because consumers understand the<br />

animals' cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs and consequently<br />

can l<strong>in</strong>k these mean<strong>in</strong>gs to a product. <strong>The</strong>refore,<br />

the cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> animals may lie at the<br />

core <strong>of</strong> the mean<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> animal trade<br />

characters. This paper describes a method for<br />

elicit<strong>in</strong>g character mean<strong>in</strong>gs, presents a<br />

qualitative analysis <strong>of</strong> the cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong><br />

four animal characters, and discusses the<br />

broader implications that these results have for<br />

advertis<strong>in</strong>g research and practice. This<br />

qualitative study <strong>of</strong> animal mean<strong>in</strong>gs is<br />

motivated by several issues: Understand<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs that consumers assign to<br />

animal characters will assist <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g<br />

successful advertis<strong>in</strong>g campaigns; practitioners<br />

can create characters that embody desired<br />

brand mean<strong>in</strong>gs while avoid<strong>in</strong>g characters with<br />

negative associations. In addition, by<br />

highlight<strong>in</strong>g an underutilized research method by<br />

which the cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> characters can<br />

be elicited, this paper presents a way for<br />

practitioners, researchers, and regulators to<br />

understand what messages specific characters<br />

are communicat<strong>in</strong>g to their audiences. This<br />

method may be useful <strong>in</strong> other types <strong>of</strong><br />

advertis<strong>in</strong>g research as well. Researchers have,<br />

<strong>in</strong> the past, asked for measures <strong>of</strong> cultural<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>g for celebrity endorsers (McCracken<br />

1989) and for symbolic advertis<strong>in</strong>g images (Scott<br />

1994), as well. F<strong>in</strong>ally, by show<strong>in</strong>g that animal<br />

characters have common cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs,<br />

this paper builds support for one <strong>of</strong> the first<br />

empirical explanations <strong>of</strong> how trade characters<br />

"work" <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g, and creates a foundation<br />

for future trade character research.<br />

<strong>The</strong> next section <strong>of</strong> the paper will present<br />

the theories used to illum<strong>in</strong>ate the research<br />

question: Do there exist shared mean<strong>in</strong>gs that<br />

consumers associate with specific animal<br />

characters? If so, how can these mean<strong>in</strong>gs be<br />

elicited, and what are their common themes?<br />

<strong>The</strong> third section will <strong>in</strong>troduce a method by<br />

which the cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> characters can<br />

be elicited, and will present the procedures used<br />

<strong>in</strong> this research study. <strong>The</strong> fourth section will<br />

discuss the results <strong>of</strong> the study, and the last<br />

section will draw general conclusions.<br />

Conceptual Development <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Research Question It has been suggested that<br />

advertis<strong>in</strong>g functions, <strong>in</strong> general, by attempt<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to l<strong>in</strong>k a product with an image that elicits<br />

10<br />

desirable emotions and ideas (McCracken 1986).<br />

For example, the image <strong>of</strong> a child may <strong>in</strong>voke<br />

feel<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> pleasure, nostalgia, and playfulness. By<br />

show<strong>in</strong>g a product next to such an image,<br />

advertis<strong>in</strong>g encourages consumers to associate<br />

the product with the image. Through this<br />

association, the product acquires the image's<br />

cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Trade characters may be one type <strong>of</strong><br />

image that advertisers use because these<br />

characters possess learned cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se mean<strong>in</strong>gs are similar to the personalities<br />

that consumers associate with characters from<br />

other sources such as movies, cartoons, and<br />

comic books. For example, Mickey Mouse is<br />

viewed as a "nice guy," while Bugs Bunny is seen<br />

as clever, but mischievous. Individuals do not<br />

<strong>in</strong>vent their own mean<strong>in</strong>g for cultural symbols;<br />

they must learn what each symbol means <strong>in</strong> their<br />

culture (Berger 1984) based on their experiences<br />

with the character. For example, consumers'<br />

ideas about the mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> "elephant" are<br />

shaped by Dumbo movies and African safari TV<br />

programs, and are colored by news stories about<br />

a rampag<strong>in</strong>g elephant that trampled its tra<strong>in</strong>er.<br />

Consequently, although each <strong>in</strong>dividual br<strong>in</strong>gs his<br />

or her own experience to the mean<strong>in</strong>g ascription<br />

process, consensus <strong>of</strong> character mean<strong>in</strong>g across<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividuals is possible through common cultural<br />

experience.<br />

In advertis<strong>in</strong>g, trade characters' mean<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

are used to visually represent the product<br />

attributes (Zacher 1967) or the advertis<strong>in</strong>g<br />

message (Kleppner 1966). For example, Mr.<br />

Peanut embodies sophistication (Kapnick 1992),<br />

the Pillsbury Doughboy symbolizes fun (PR<br />

Newswire 1990), and the lonely Maytag repairman<br />

stands for reliability (Elliott 1992). However, the<br />

consumer must correctly decode the trade<br />

character's mean<strong>in</strong>g before it can have an<br />

impact (McCracken 1986). <strong>The</strong>refore, characters'<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>gs must be easily understood by<br />

consumers if they are to correctly <strong>in</strong>terpret the<br />

character's message. As a result, advertisers<br />

frequently use animal trade characters (Callcott<br />

and Lee 1994) because consumers are thought<br />

to have learned the animals' cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs,<br />

and consequently are likely to correctly decode<br />

the advertis<strong>in</strong>g message.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first step <strong>in</strong> exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the association<br />

between animal trade characters and the<br />

products they promote is to explore the symbolic<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>gs conveyed by the animals used <strong>in</strong> these<br />

advertisements. That is, if an advertiser places a<br />

bear (e.g., Snuggle) or a dog (e.g., Spuds<br />

McKenzie) next to his product, what do these

animals represent to the audience? Rather than<br />

exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>dividual animal characters, however,<br />

it is necessary to first study an animal's general<br />

cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g. This is because the animal<br />

category (e.g., bear, dog, etc.) provides the<br />

primary, or core, mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> an <strong>in</strong>dividual<br />

character. Although an advertiser can choose to<br />

highlight certa<strong>in</strong> animal mean<strong>in</strong>gs over others<br />

(e.g., "s<strong>of</strong>tness" for Snuggle Bear and "wildness"<br />

for Smokey Bear), the core set <strong>of</strong> animal<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>gs dictate what is possible for that<br />

character to express. Snuggle fabric s<strong>of</strong>tener<br />

would not f<strong>in</strong>d it easy to use a porcup<strong>in</strong>e, pig, or<br />

flam<strong>in</strong>go to express "s<strong>of</strong>tness."<br />

In addition, by study<strong>in</strong>g the broad animal<br />

category to which the character belongs, it is<br />

possible to make generalizations that can help<br />

practitioners create and use animal characters<br />

effectively. For example, if advertisers know that<br />

the animal "cat" shares several positive core<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>gs, they can create cat characters that<br />

capitalize on those mean<strong>in</strong>gs. Alternatively, if<br />

"cat" mean<strong>in</strong>gs conta<strong>in</strong> negative attributes that<br />

reflect badly on the associated product,<br />

advertisers may want to use a different<br />

character.<br />

Method<br />

It is difficult to explore the perceived mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

a trade character by ask<strong>in</strong>g subjects directly, as<br />

their responses tend to be superficial and<br />

descriptive. "Smokey Bear? Oh, he's brown and<br />

wears a hat." Other qualitative methods, such as<br />

<strong>in</strong>-depth <strong>in</strong>terview<strong>in</strong>g, tend to be time- and labor<strong>in</strong>tensive<br />

C features that advertisers may want to<br />

avoid. As an alternative, word association is an<br />

easy and efficient method for explor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

psychological mean<strong>in</strong>g. It can be adm<strong>in</strong>istered<br />

to a group and can elicit the mean<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> more<br />

than one animal per session, yet provides rich<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation regard<strong>in</strong>g cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g. Szalay<br />

and Deese (1978) state that because a word<br />

association task does not require subjects to<br />

communicate their <strong>in</strong>tentions, it decreases<br />

subjects' rationalizations, and it taps associations<br />

that are difficult to express or expla<strong>in</strong>. Further,<br />

word association does not require thoughts to be<br />

expressed <strong>in</strong> a structural manner. Instead, this<br />

technique produces expressions <strong>of</strong> thought that<br />

are immediate and spontaneous, and this<br />

spontaneity, along with an imposed time<br />

constra<strong>in</strong>t, is thought to reduce subjects' selfmonitor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and conscious edit<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> responses.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, the method reduces experimenter bias<br />

because no organization or categories are<br />

11<br />

imposed on subjects to limit their responses C a<br />

primary draw-back <strong>of</strong> quantitative research. <strong>The</strong><br />

word association method is not new; other<br />

market<strong>in</strong>g and advertis<strong>in</strong>g researchers have used<br />

it to understand how consumers perceive<br />

products (Kle<strong>in</strong>e and Kernan 1991) and to<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>e a product's attributes to aid <strong>in</strong> product<br />

position<strong>in</strong>g (Friedmann 1986). However, perhaps<br />

because it is "old hat," this method has been<br />

consistently overlooked and underutilized <strong>in</strong><br />

consumer behavior research.<br />

In the present study, <strong>in</strong>formants were asked<br />

to respond to verbal animal names dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

word association task (e.g., "bear") rather than to<br />

visual images <strong>of</strong> the animal. Verbal animal names<br />

are thought to elicit broad responses that reflect<br />

much <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>formation that an <strong>in</strong>dividual has<br />

learned to associate with the category, "bear." In<br />

contrast, the way an animal is visually portrayed<br />

can narrow its mean<strong>in</strong>g (Berger 1984). A realistic<br />

picture <strong>of</strong> a bear may elicit a different part <strong>of</strong> the<br />

core mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> "bear" than a cartoon bear.<br />

Images <strong>of</strong> actual trade characters, such as<br />

Smokey Bear or Snuggle, may elicit even narrower<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>gs associated only with those characters.<br />

<strong>The</strong>refore, verbal animal names were used to<br />

generate broad, complete responses. However, it<br />

is possible that advertisers could use both verbal<br />

and visual animals <strong>in</strong> a word association task<br />

when creat<strong>in</strong>g characters. Responses to the<br />

verbal animal name would provide core<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>gs, while responses to the visual character<br />

would provide a measure <strong>of</strong> how successfully the<br />

particular representation <strong>of</strong> an animal captured<br />

desired mean<strong>in</strong>gs. This possibility will be discussed<br />

further <strong>in</strong> the conclusion section <strong>of</strong> this paper.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>formants for this study were 21 male<br />

and 15 female undergraduate students enrolled<br />

<strong>in</strong> an advertis<strong>in</strong>g management course at a major<br />

state university. Students participated <strong>in</strong> the study<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g their regular class time. Of these<br />

respondents, 92% were between the ages <strong>of</strong> 20<br />

and 25. <strong>The</strong> use <strong>of</strong> this student sample precludes<br />

conclud<strong>in</strong>g that the results <strong>of</strong> this study reflect the<br />

"true" cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> each animal. However,<br />

this sample is useful to show that a common<br />

cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g for each animal exists <strong>in</strong> a<br />

homogeneous population and can be elicited<br />

through research, whether that population is<br />

composed <strong>of</strong> undergraduate students or other<br />

target markets <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest to advertisers. Each<br />

<strong>in</strong>formant received a package conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a<br />

cover page, an <strong>in</strong>struction page, and five word<br />

association sheets.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>structions for the word association<br />

task were read aloud and <strong>in</strong>formants' questions

egard<strong>in</strong>g the task were answered. For each word<br />

association task, respondents had one m<strong>in</strong>ute to<br />

write one-word descriptions <strong>of</strong> whatever came to<br />

m<strong>in</strong>d when they thought about the animal listed<br />

at the top <strong>of</strong> the page (Szalay and Deese 1978).<br />

Informants were <strong>in</strong>structed to write these words <strong>in</strong><br />

the order <strong>in</strong> which they came to m<strong>in</strong>d and it was<br />

stressed that there were no wrong answers. <strong>The</strong><br />

first animal listed <strong>in</strong> the package was lobster,<br />

which was used as a practice task to familiarize<br />

students with the word association method. After<br />

complet<strong>in</strong>g the practice task, <strong>in</strong>formants'<br />

rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g questions about the task were<br />

answered. Respondents then completed four<br />

more animal word associations, respond<strong>in</strong>g to the<br />

words: pengu<strong>in</strong>, ant, gorilla, and raccoon. <strong>The</strong><br />

particular animals were chosen to reflect the<br />

<strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> the author; other animals could<br />

illustrate the commonality <strong>of</strong> animal mean<strong>in</strong>gs as<br />

well. <strong>The</strong> order <strong>in</strong> which the four animals were<br />

presented was randomized to control for order<br />

effects.<br />

<strong>The</strong> words generated by <strong>in</strong>formants <strong>in</strong><br />

response to the animal word association were<br />

grouped <strong>in</strong>to categories, or themes that emerged<br />

from the data. Each animal was analyzed<br />

separately, except lobster, the practice task,<br />

which was not coded. For each animal, words<br />

that were similar <strong>in</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>g or that had a<br />

common theme were grouped together. Each<br />

<strong>in</strong>formant's responses were added to the tentative<br />

themes discovered <strong>in</strong> the previous <strong>in</strong>formants'<br />

responses, thus support<strong>in</strong>g those themes or<br />

allow<strong>in</strong>g them to be changed (Strauss and Corb<strong>in</strong><br />

1990). Guidel<strong>in</strong>es suggested by Szalay and Deese<br />

(1978) were followed when identify<strong>in</strong>g common<br />

themes.<br />

Words that could not be placed <strong>in</strong>to any<br />

category were placed <strong>in</strong>to an "other" category.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se words did not have an identifiable<br />

association with the animal; they are thought to<br />

be associations to words other than the animal<br />

(i.e., cha<strong>in</strong> associations) or words that show that<br />

the respondent was th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> someth<strong>in</strong>g other<br />

than the task at hand. <strong>The</strong>re were only 10 to 16 <strong>of</strong><br />

these words for each animal.<br />

A second researcher re-classified all <strong>of</strong> the<br />

response words <strong>in</strong>to the categories to check the<br />

soundness <strong>of</strong> the themes. <strong>The</strong>re was an <strong>in</strong>itial 86%<br />

agreement between researchers; disagreements<br />

were resolved through discussion and re-analysis<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formant responses. <strong>The</strong> response words for all<br />

<strong>of</strong> the animals are available from the author.<br />

12<br />

COGNITIVE MAP OF PENGUIN THEMES<br />

<strong>The</strong> themes elicited <strong>in</strong> response to each animal<br />

were illustrated us<strong>in</strong>g cognitive maps, represent<strong>in</strong>g<br />

a pictorial overview <strong>of</strong> each animal's mean<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

<strong>The</strong> cognitive map summarizes the objects and<br />

ideas that <strong>in</strong>formants collectively associate with<br />

each animal, and organizes these associations<br />

<strong>in</strong>to mean<strong>in</strong>gful themes (Coleman 1992). <strong>The</strong><br />

cognitive map also identifies the number <strong>of</strong> times<br />

each theme was mentioned, giv<strong>in</strong>g an idea <strong>of</strong><br />

the relative importance <strong>of</strong> each theme to the<br />

animal's shared mean<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION<br />

General Results<br />

Informants mentioned between 315 and 386<br />

words <strong>in</strong> response to each animal, or<br />

approximately 9 to 11 words per <strong>in</strong>dividual. It was<br />

surpris<strong>in</strong>g that more than 90% <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formants'<br />

responses could be classified <strong>in</strong>to six or seven<br />

ma<strong>in</strong> themes for each animal. In addition,<br />

<strong>in</strong>formants' words were easily coded <strong>in</strong>to these<br />

themes, reflect<strong>in</strong>g a high degree <strong>of</strong> similarity<br />

between respondents. Also, words with the highest<br />

frequencies were mentioned by 8 to 25<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividuals, which suggests a high degree <strong>of</strong><br />

consistency across <strong>in</strong>dividuals' responses. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

results support the idea that there exist shared<br />

cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs that consumers generally<br />

associate with animals, and that these mean<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

can be elicited through word association.<br />

Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, although it was not the <strong>in</strong>tent<br />

at the outset, the themes that emerged from the<br />

data were remarkably similar between animals.<br />

<strong>The</strong> primary themes mentioned by <strong>in</strong>formants<br />

<strong>in</strong>clude: (a) Appearance, (b) Habitat, (c)<br />

Personality, (d) Human/animal <strong>in</strong>teraction, (e)<br />

Popular culture, and (f) Behavior. <strong>The</strong>se six<br />

categories seem to be most salient for<br />

consumers, and may <strong>of</strong>fer the greatest help <strong>in</strong><br />

creat<strong>in</strong>g animal characters for use <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g<br />

campaigns. Appearance summarizes <strong>in</strong>formants'<br />

mental images <strong>of</strong> the animal C how they expect<br />

the animal to look; Habitat describes <strong>in</strong>formants'<br />

expectations <strong>of</strong> where these animals live and the<br />

objects that surround them; Personality represents<br />

the personality traits that <strong>in</strong>formants associate with<br />

each animal; Human/animal <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

describes how humans coexist and <strong>in</strong>teract with<br />

these animals; while Behavior describes their<br />

typical actions. Popular culture highlights cultural<br />

references that already exist for each animal,

Fig. 1.<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g sources such as television programs,<br />

movies, books, and ads. <strong>The</strong> themes for each<br />

animal are given below <strong>in</strong> greater detail.<br />

Pengu<strong>in</strong><br />

A cognitive map <strong>of</strong> the themes associated with<br />

"pengu<strong>in</strong>," along with the frequency with which<br />

they were mentioned, are shown <strong>in</strong> Figure 1. <strong>The</strong><br />

dom<strong>in</strong>ant themes that emerge from the data are<br />

Habitat and Appearance.<br />

13<br />

Habitat <strong>in</strong>cludes a natural habitat made up <strong>of</strong> the<br />

subthemes <strong>of</strong>: (a) ice and snow, (b) cold, (c)<br />

places such as Antarctica and the South Pole,<br />

and (d) water. Informants also listed other<br />

<strong>in</strong>habitants <strong>of</strong> this environment such as fish, polar<br />

bears, and whales. Informants also mentioned<br />

Appearance as an important pengu<strong>in</strong> theme,<br />

focus<strong>in</strong>g on the subthemes <strong>of</strong>: (a) color, which<br />

was mostly black and white, (b) body parts such<br />

as w<strong>in</strong>gs, beaks, and feet, and (c) the formal<br />

tuxedo that pengu<strong>in</strong>s seem to be wear<strong>in</strong>g.

Fig. 2.<br />

Tuxedo was the most <strong>of</strong>ten mentioned word, with<br />

23 mentions. This strong association seems to<br />

have affected other themes, as discussed below.<br />

Both <strong>of</strong> the dom<strong>in</strong>ant themes suggest that a<br />

pengu<strong>in</strong> is associated with rich visual imagery.<br />

When confronted with the word "pengu<strong>in</strong>," it<br />

appears that <strong>in</strong>dividuals conjure up an image <strong>of</strong><br />

a pengu<strong>in</strong>, and describe him (Appearance) and<br />

his surround<strong>in</strong>gs (Habitat). This <strong>in</strong>terpretation is<br />

supported by a third theme, Behavior, which was<br />

mentioned less <strong>of</strong>ten. This category <strong>in</strong>cludes the<br />

subthemes <strong>of</strong>: (a) waddle, (b) swim, and (c) other<br />

actions, which also contribute to visual imagery.<br />

14<br />

Behavior was mentioned 44 times, suggest<strong>in</strong>g that<br />

respondents frequently visualize the pengu<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

motion.<br />

COGNITIVE MAP OF ANT THEMES<br />

In analyz<strong>in</strong>g the dom<strong>in</strong>ant themes, it seems that<br />

pengu<strong>in</strong>s are viewed as hav<strong>in</strong>g little <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

with humans. <strong>The</strong> pengu<strong>in</strong> appears to be isolated<br />

from all but a few Eskimos (accord<strong>in</strong>g to two<br />

<strong>in</strong>formants) except when viewed <strong>in</strong> a man-made<br />

habitat (e.g., "Sea World"), and even that type <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>teraction is rarely mentioned (2% <strong>of</strong> the time).

This lack <strong>of</strong> human/pengu<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>teraction is not<br />

surpris<strong>in</strong>g given pengu<strong>in</strong>s' remote location <strong>in</strong> the<br />

world, and the fact that they are removed from<br />

<strong>in</strong>formants' daily experiences. Another theme,<br />

Personality, is characterized by a duality; for the<br />

most part, pengu<strong>in</strong>s are personified as silly<br />

creatures (e.g., cute, funny, go<strong>of</strong>y, playful, etc.),<br />

but they also can be viewed as formal animals<br />

(e.g., dist<strong>in</strong>guished, classy, behaved, mannered,<br />

etc.), even by the same <strong>in</strong>dividuals. This<br />

contradiction may stem from the fact that<br />

pengu<strong>in</strong>s are strange-look<strong>in</strong>g members <strong>of</strong> the<br />

bird family and waddle comically <strong>in</strong>stead <strong>of</strong><br />

fly<strong>in</strong>g, but also appear to wear<strong>in</strong>g a tuxedo, a<br />

cultural symbol <strong>of</strong> formality and manners.<br />

<strong>The</strong> rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g pengu<strong>in</strong> themes are<br />

Popular culture and Categories. Pengu<strong>in</strong>s are<br />

associated with a surpris<strong>in</strong>gly large number <strong>of</strong><br />

popular culture references <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g movies,<br />

videogames, mascots, and cartoons. Categories<br />

refers to the hierarchical categorization <strong>of</strong><br />

objects, <strong>in</strong> which an object can be placed <strong>in</strong> a<br />

superset (generalization hierarchy) or a subset<br />

(part hierarchy) (Anderson 1990). For example, a<br />

pengu<strong>in</strong> is a bird (superset), and a type <strong>of</strong><br />

pengu<strong>in</strong> is an emperor (subset). In the same way,<br />

a group <strong>of</strong> pengu<strong>in</strong>s is called a flock, or a herd<br />

(at least for one respondent).<br />

Ant<br />

A cognitive map <strong>of</strong> the "ant" themes is shown <strong>in</strong><br />

Figure 2. <strong>The</strong> three dom<strong>in</strong>ant ant themes are:<br />

Categories, Habitat, and Human/ant <strong>in</strong>teraction.<br />

Categories <strong>in</strong>cludes: (a) type <strong>of</strong> ant, such as red<br />

or army; (b) name <strong>of</strong> ant, such as worker or<br />

queen; (c) group <strong>of</strong> ants, such as colony; and (d)<br />

classification <strong>of</strong> ant, such as <strong>in</strong>sect. <strong>The</strong><br />

importance <strong>of</strong> this theme for ant contrasts sharply<br />

with that for pengu<strong>in</strong>; Categories was mentioned<br />

104 times for ant, but only 16 times for pengu<strong>in</strong>.<br />

This suggests that the ant themes are less<br />

associated with images, and more associated<br />

with verbal or propositional knowledge (Anderson<br />

1990). That is, when asked to respond to the word<br />

"ant," it appears that respondents retrieve verbal<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation that they have learned <strong>in</strong> the past,<br />

such as: the head ant is called the queen; the<br />

male ant is called the drone; ants live <strong>in</strong> colonies;<br />

etc. This <strong>in</strong>terpretation is supported by another<br />

dom<strong>in</strong>ant theme: Habitat, where the subthemes<br />

<strong>of</strong> (a) hill and (b) man-made habitat also appear<br />

to conta<strong>in</strong> verbal associations. For example, the<br />

most-<strong>of</strong>ten mentioned words <strong>in</strong> each subtheme,<br />

"hill" and "farm," could be elicited with a fill-<strong>in</strong>-the-<br />

15<br />

blank word task (i.e., "ant____"). <strong>The</strong> same cannot<br />

be said for pengu<strong>in</strong> (e.g., "pengu<strong>in</strong> ice," "pengu<strong>in</strong><br />

cold," etc.). Some imagery is associated with ant,<br />

though, as seen <strong>in</strong> the Habitat subtheme <strong>of</strong> (c)<br />

picnic. For the most part, however, other themes<br />

support verbal, non-imagery based associations<br />

for ant. For example, the ant's image-based<br />

themes, Appearance and Behavior, conta<strong>in</strong> far<br />

fewer words (31 and 7) than do these same<br />

categories for pengu<strong>in</strong> (103 and 44). Also, many<br />

<strong>of</strong> the words <strong>in</strong> Appearance, such as antenna,<br />

thorax, and abdomen, seem associated with<br />

knowledge propositions, rather than image.<br />

Surpris<strong>in</strong>gly, even the Popular culture theme<br />

supports a verbal view because many <strong>of</strong> the<br />

responses <strong>in</strong> this category make use <strong>of</strong> word play<br />

such as "Aunt Bea" and "antichrist."<br />

A dom<strong>in</strong>ant theme for ant that did not exist<br />

for pengu<strong>in</strong> is Human/ant <strong>in</strong>teraction. This focus on<br />

<strong>in</strong>teraction is understandable given that ants are<br />

usually part <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formants' daily environment and<br />

experience. In this category, ants <strong>in</strong>teract with<br />

humans by annoy<strong>in</strong>g them and caus<strong>in</strong>g them<br />

pa<strong>in</strong>; "bite" was mentioned 19 times by<br />

respondents. Humans <strong>in</strong>teract with ants as<br />

exterm<strong>in</strong>ators; we kill them. It is surpris<strong>in</strong>g then, that<br />

under the theme Personality, ants are personified<br />

as hav<strong>in</strong>g more positive than negative qualities.<br />

Words like "strong," "hard-work<strong>in</strong>g," and<br />

"determ<strong>in</strong>ed" are used by respondents. Perhaps<br />